full article:

Context

Hypothyroidism is a common endocrine disorder and a significant cause of pericardial effusion1. Hormone replacement therapy is the cornerstone of treatment for hypothyroidism and, after initiation of therapy, regular follow-up of the patients is indicated. Compliance with hormone therapy is also an important issue, especially for patients in rural and remote areas. Subclinical hypothyroidism is a frequent entity in daily clinical practice and is defined by elevated levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) with normal levels of free thyroid hormones in serum2. However, large pericardial effusions due to hypothyroidism are rare1,3 and their clinical management is always challenging. Herein, the case of a 70-year-old rural woman with a massive pericardial effusion due to Hashimoto’s disease is presented. The patient provided written consent to appear in the article.

Issues

Case report

A 70-year-old female from a rural village in Crete, Greece, was admitted to our hospital with a urinary tract infection. Her medical history included arterial hypertension, dementia and hypothyroidism due to Hashimoto’s disease. She was under replacement therapy with levothyroxine 100 µg once a day. She had suffered four ischaemic strokes during the past 20 years and was under treatment with acetylsalicylic acid 160 mg OD (once daily). She had a homozygous methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T mutation with elevated homocysteine levels. Two years previously, the patient had had an episode of pericarditis due to hypothyroidism and had undergone a computed tomography (CT)-guided pericardiocentesis. The patient did not have regular follow-up after the procedure and did not take the hormone replacement therapy properly.

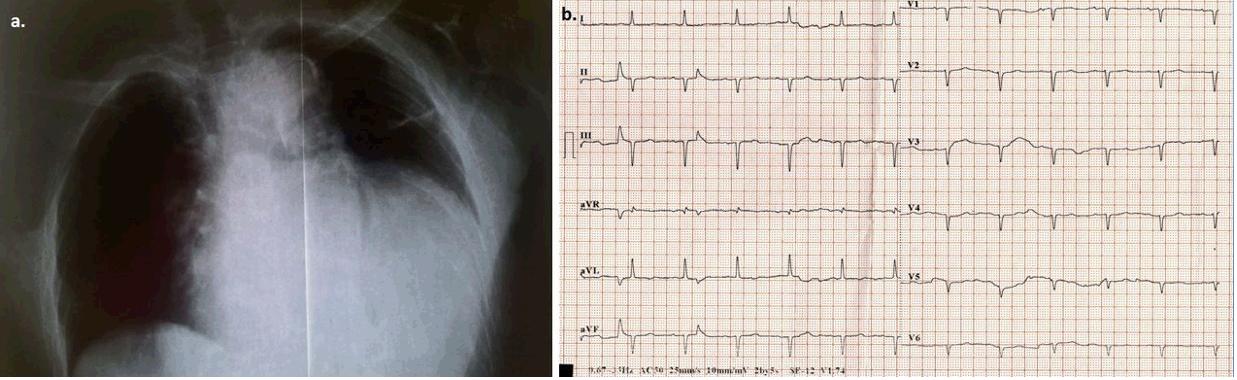

On admission, the patient was haemodynamically stable without fever, or chest pain. Laboratory tests showed high white blood cells (WBC) of 18.000 K/μL, an elevated level of C-reactive protein (CRP) of 5.4 mg/dL (normal limit: 0.08–0.8 mg/dL) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 3 mm in the first hour. The chest X-ray (Fig1a) showed a possible pericardial effusion, which was an incidental finding. The patient was referred to emergency bedside echocardiography, which revealed a massive pericardial effusion without evidence of cardiac tamponade, normal left ventricular systolic function and normal wall thickness with ejection fraction of 60%. Beck's triad was absent. The electrocardiograph (ECG) is shown in Figure 1b. There was no dynamic change from the patient’s baseline ECG.During hospitalisation, the patient was under antibiotic treatment with levofloxacin, while for the possible pericarditis she was under treatment with ibuprofen 600 mg every 8 hours and colchicine 0.5 mg OD according to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines4. On the third day, she presented with acute kidney failure, which was considered drug-induced and ibuprofen and colchicine were replaced with prednisone 30 mg intravenously OD (0.50 mg/kg/day)4. WBC and CRP decreased gradually and were within the normal limits on the sixth day of hospitalisation. Virological blood tests for herpesviruses (cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus), enteroviruses (echoviruses, coxsackieviruses), adenoviruses, parvovirus and human immunodeficiency virus were negative. Mantoux tuberculin skin test for tuberculosis was also negative. Rheumatoid factor, anti-nuclear antibodies and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative. Thyroid hormones were consistent with subclinical hypothyroidism: TSH 30.25 mIU/L (normal limits: 0.25–3.43); free thyroxin 4 0.81 ng/dL (normal limits: 0.7–1.94). Thyroid antibodies were: anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody >1000 IU/mL (normal limit: <5.61) and anti-thyroglobulin 2.79 IU/mL (normal limit: <4.11).

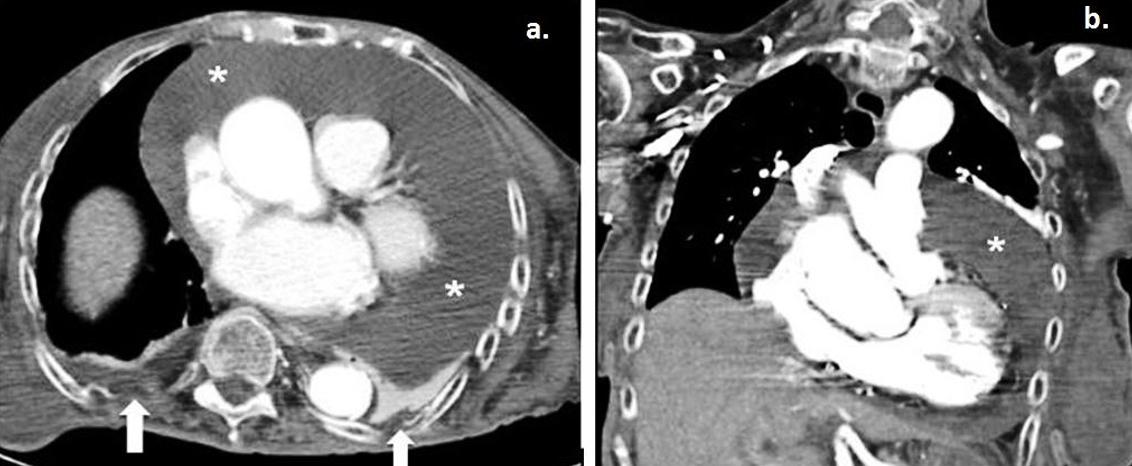

A new echocardiograph and chest CT (Fig2a,b) were performed, revealing a massive pericardial effusion with no evidence of aortic dissection or neoplastic pericardial involvement and without echocardiographic findings of cardiac tamponade. According to the ESC position statement on triage strategy for pericardial diseases5, the patient had a score of 5 and, despite the absence of cardiac tamponade, a pericardiocentesis was performed after 48 hours. During the procedure, 1070 mL of pericardial fluid was drained and analysis showed exudate. Cytological examination was negative for malignancy. Pericardial fluid culture was negative. Consequently, subclinical hypothyroidism was considered the cause of the pericardial effusion and the patient was treated with 125 µg levothyroxine orally OD.

Figure 1: a. Front chest X-ray demonstrates marked enlargement of the cardiac outline. b. Electrocardiograph (ECG) on admission. Sinus rhythm (~85 bpm), left axis deviation, Q-waves in leads II, III, and poor progression of R-waves in the precordial leads, flattened T-waves in all leads, low QRS voltage in all precordial leads. There was no dynamic change from the patient’s baseline ECG.

Figure 1: a. Front chest X-ray demonstrates marked enlargement of the cardiac outline. b. Electrocardiograph (ECG) on admission. Sinus rhythm (~85 bpm), left axis deviation, Q-waves in leads II, III, and poor progression of R-waves in the precordial leads, flattened T-waves in all leads, low QRS voltage in all precordial leads. There was no dynamic change from the patient’s baseline ECG.

Figure 2: a. Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography and coronal maximum intensity projection–reconstruction during the patient’s hospitalisation revealed a large global pericardial effusion (*). b. Small bilateral pleural effusions are also noted (white arrows).

Figure 2: a. Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography and coronal maximum intensity projection–reconstruction during the patient’s hospitalisation revealed a large global pericardial effusion (*). b. Small bilateral pleural effusions are also noted (white arrows).

Lessons learned

Massive pericardial effusion is always an important clinical finding, even if incidental and, when it occurs, cardiac tamponade should be excluded and a diagnostic workup should be performed6. Hypothyroidism should always be included in the differential diagnosis in cases of an unexplained massive pericardial effusion2,3,5,7. Once the diagnosis has been established and treatment has started, pericardial fluid regresses slowly and can be gone several months after the initiation of hormone replacement therapy3.

Pericardial effusion due to hypothyroidism rarely causes cardiac tamponade7 and it tends to be chronic because it progresses slowly. Whenever a pericardial emission progresses slowly, the pericardial sac has enough time to stretch and can subsequently contain a large amount of pericardial fluid without a significant rise in intrapericardial pressure8.In the absence of ongoing inflammation treatment for chronic idiopathic effusions of any size with aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, colchicine and/or steroids are not effective6. However, in the present case, it was difficult to distinguish the origin of the elevated inflammation markers (WBC, CRP) and it was initially decided to treat both the urinary tract infection and the possible pericarditis.

A scoring system was introduced by Halpern et al9 to guide the decision for pericardial drainage based on clinical factors, the echocardiographic assessment of haemodynamics and the size of the pericardial effusion. The ESC Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases proposed a new stepwise scoring system for the triage of patients requiring pericardiocentesis5. In the present patient, there was no clinical or echocardiographic sign of cardiac tamponade. However, due to the large pericardial effusion, the decision to perform a late echo-guided pericardiocentesis was made.

The incidence of subclinical hypothyroidism varies between 4 and 10% depending on the age, gender and population studied10,11. It is more frequent in iodine-sufficient regions and in individuals of white, Caucasian origin11,12. The consequences of subclinical hypothyroidism are variable and may depend on the degree of elevation of TSH along with the duration of the disorder. Subclinical hypothyroidism is generally classified according to the elevation in TSH: a more severely increased TSH value (>10 mIU/L) as in the present case or mildly increased TSH levels (4.0–10.0 mIU/L), which accounts for around 90% of cases11,12. However, there has been a widening of the reference range for TSH in elderly people, and a mild TSH elevation (4.0–7.0 mIU/L) in patients >80 years should be considered a physiological adaptation to aging11,13. Furthermore, an initially raised TSH and free thyroxin 4 within normal range should be followed-up with a repeat measurement after a 2–3 month interval11. Consequently, the management of this metabolic disorder, especially in elderly patients in the rural health setting, is challenging, because the primary care physician has to decide whether the patient should initiate treatment with levothyroxine.

In elderly individuals, initiation of treatment for subclinical hypothyroidism should be personalised and closely monitored11. A wait-and-see strategy is preferred, avoiding hormone replacement therapy in patients >80–85 years old with TSH ≤10 mIU/L11. In patients between 60 and 70 years old, the decision of when to initiate treatment should be based on the evaluation of several factors, including frailty, comorbidities and degree of TSH elevation. For patients of these ages, a small dose of levothyroxine should be initiated (25 or 50 μg daily), and the dose should be increased by 25 μg/day every 14–21 days until a full replacement dose is reached11. TSH level should be re-assessed 2 months after the initiation of treatment, and dose adjustments should be made accordingly. According to the European Thyroid Association (ETA) Guidelines for Subclinical Hypothyroidism11, the aim for most adult patients is a stable TSH in the lower half of the reference range (0.4–2.5 mIU/L), although for patients >70–75 years, a higher target for TSH (around 1–5 mIU/L) is also acceptable. Once the patients achieve desirable levels of serum TSH, TSH should be monitored annually at least.

Data on the use of the hormone replacement therapy in rural areas are sparse in the literature and the compliance of the patients in such areas has not been well established. The study of rural and remote areas is interesting and challenging because rural and remote patients usually have special cultural conditions in combination with limited access to healthcare services. In the present case, the patient lived in a remote and rural village on the island of Crete with limited access to primary care services. Consequently, she did not have regular follow-up and hypothyroidism was not treated properly.

In conclusion, this was a rare case of a patient with chronic massive pericardial effusion due to subclinical hypothyroidism without cardiac tamponade. Hypothyroidism should be included in the differential diagnosis of pericardial effusion, especially in cases of unexplained pericardial fluid. Pericardial effusions due to hypothyroidism grow slowly and subclinical hypothyroidism rarely show signs and symptoms and can be underdiagnosed. Initiation of hormone replacement therapy should be personalised in elderly patients. However, TSH levels >10 mIU/L usually require therapy with levothyroxine in order to prevent the adverse events due to this ‘silent’ metabolic disorder. Patients who live in rural and remote places usually do not have regular follow-up of systemic diseases such as hypothyroidism. The ESC position statement on triage strategy for pericardial diseases5 is a valuable clinical tool to estimate the necessity for pericardial drainage in such cases.