full article:

Context

Providing high quality care to the small towns of the USA is a formidable challenge for hospitals. There is a shortage of physicians willing and/or able to work in this setting for multiple reasons1. Although about 20% of Americans live in a rural setting, only 9% of physicians practice there. Many attempts have been made to attract physicians to the rural setting2,3.

Primary care is now often provided by physician assistants and nurse practitioners not as familiar with inpatient work. Outpatient providers often seek to decrease their inpatient duties due to lifestyle issues and feel uncomfortable with providing care in this setting. It may be difficult in rural areas to maintain an appropriate level of proficiency in inpatient medicine. Many providers have transitioned from self-employment to hospital employment, and rural hospitals are seeking effective provider staffing models to manage their clinic and inpatient services.

Three existing models

In the traditional rural hospital model, primary care providers (PCPs) care for their own patients in the hospital and arrange call schedules to share coverage for nights and weekends, and for patients not on their primary care panel. This model typically involves morning rounds where the PCP sees the patient in the hospital in the morning, writes orders and notes, and then goes to the clinic to do outpatient care. At the end of the day, usually another visit is made to the hospital to see patients, do admissions, and do other paperwork.

In the usual ‘hospitalist’ model, designated providers care only for inpatients. They have no role in the clinic and often have a shift-work approach to inpatient duties4.

The term ‘hybrid rotating hospitalist’ has been used to describe outpatient providers taking turns caring for the inpatients in a rural hospital setting5. In this model, the outpatient provider takes some set time off from part or all outpatient duties and spends that time caring for inpatients while the other providers in his or her group continue working in the clinic. For example, four PCPs may share a schedule where each takes one week out of every four to round on all of the group’s patients that are in the hospital (or, in a rural setting, perhaps all the patients in the hospital). They may also rotate night call in a one-in-four rotation.

Issues

In January 2014, several internal medicine physicians who worked at larger hospitals agreed to set up a program for inpatient and consultative work at Summit Pacific Medical Center in Elma, Washington State. The hospital had recently moved to a new facility and experienced increased admissions and acuity. Previously it had used a traditional model, and was using locum hospitalists at the time the model was implemented.

Setting

The Summit Pacific Medical Center has 10 inpatient beds. The town where the hospital is located has a population of approximately 3100. The county has a population of approximately 72 5006. There is one other hospital in the county. The USA has an average of 2.6 physicians per 1000 people7, and the county has 0.58.

The hospital has the following other relevant departments:

- radiology – X-ray, portable X-ray, ultrasound and CT scan. A portable MRI is available one to two days per week. Since starting the project, echocardiogram capability has been added

- laboratory – routine chemistry, hematology, basic microbiology testing. There is no on-site blood bank

- clinic – three primary care clinics owned by the hospital on-site and in the area, which are staffed primarily with family nurse practitioners, along with family practice physicians. These three clinics are all in the hospital system with the same electronic medical record. All providers are hospital employees

- emergency room (ER) – staffed with physicians on site, 24 hours per day

- urgent care service: open daily with nurse practitioner and physician assistant staffing

- pharmacy – full-time pharmacist on site. Tele-pharmacy assists in the review and processing of orders and input after hours.

Staffing

The internists selected are required to have board certification and experience in inpatient and outpatient work. They are encouraged to continue to work part of the time in a larger hospital, where there is an intensive care unit, access to surgeons and at least some internal medicine subspecialties (all are currently doing so). This is purposeful to encourage an exposure to norms, procedures, and specialist opinion, which hopefully encourages maintenance of proficiency in inpatient medicine.

Schedule

A board-certified internal medicine physician is on duty at all times. The inpatients are seen in the morning generally, and new admissions are seen the same day if they arrive before 5 pm, or if they are overly complex and need to be seen that night. (‘Admission’ refers to any patient received for care on the inpatient unit, whether that patient is designated ‘inpatient’, ‘observation’ or otherwise by current billing categories.) Between 5 pm and 8 am, the internist receives the report on any admissions by phone from the ER physician and approves or rejects admission. If the ER physician requests, or if medically needed, the internist comes in person to evaluate the patient.

On weekday afternoons, four patient slots are scheduled for outpatient consultation. These patients are referred primarily from the physician assistants and nurse practitioners but also from the family practice physicians. The internist acts as consultant to assist the PCPs with complex cases and specific questions and procedures. If the internist finds that he or she cannot adequately answer the question, or depending on patient need, the patient is referred to subspecialty care in a larger town. There is no requirement for the PCPs to use this service – they can refer directly to the subspecialist as they see fit.

The schedule is set up such that there is one clinic patient per hour. With this low number, the internist is also thereby available for emergencies on the wards, for consultation from the emergency room, and other duties as needed. The time allotted also allows for phone consultation with subspecialists when questions can be answered without a full referral to a subspecialist. The providers can schedule extra patients in the clinic as they see fit. Initially these slots were often not filled but, after several months, the slots were typically filled and often the internists requested over-booking to see patients they knew from the ward and outpatient settings that needed close follow-up (Appendix A).

The internists worked either part-time or full-time at larger hospitals 50–80 km from Summit Pacific. Two maintained a primary care practice privately. Most went home at night, although they could stay onsite because housing was provided. They all worked part-time at Summit Pacific.

Lessons learned

Potential benefits

Access to expanded care on site: Having a board-certified internist on site with familiarity with inpatient and outpatient work may increase access and decrease referrals (Appendix B). At the time of this model’s implementation, Summit Pacific Medical Center employed no internal medicine physicians despite attempts to recruit them. Local internists, following national trends, have tended toward complete hospitalist-model jobs or clinic-only work, or have retired.

A model that fits: Internal medicine training is a mix of inpatient work, primary care work, and subspecialist work. The model has the care of inpatients in the hospital as its core. The addition of the consultation clinic greatly assists the community PCPs in their work. The consulting internist-PCP collaboration may enhance quality of care at the local level, while providing the internist an intellectually stimulating role in the rural community (Appendixes A,B).

US hospitals have seen a dramatic shift of inpatient care to the hospitalist model over the past 20 years9. It has become increasingly difficult to sustain a model where the internist provides primary care to a group of patients and also works in the inpatient setting. The model incorporates elements of the previous system as well as the current hospitalist-only system. This unique combination appears to be a sustainable model that serves the patients well in a rural setting.

Maintenance of work–life balance: The model potentially gives the providers interesting work as well as the opportunity to achieve a good work–life balance (Appendix A). The outpatient providers are not burdened with inpatient duties that they are not interested in. The inpatient providers are still connected with patient care in the clinic and the PCPs.

Follow-up of complex patients: With the transitions of care between inpatient and outpatient, there are patients that require closer follow-up than can be ensured at their time of discharge, do not have a PCP, or for whatever reason can benefit from a follow-up visit or visits with the internists. This ‘post-discharge clinic’ approach has been used in other settings and is associated with shorter time to follow-up appointment10. In the authors’ experience, the Summit Pacific model allows for easy follow-up in the outpatient setting with the same provider group that cared for the patient inhouse.

Cost savings: This model is potentially cost-saving over a full hospitalist model in several ways. Having one provider cover for up to a week or more at a time, with home-call in the evenings, is less expensive than having providers stay in house for 24 hours.

Compensation calculation was based on assuming an internist hospitalist typically would be working in series of 7 days on and 7 days off for one full time equivalent for internal medicine, and is similar to other hospitalist salaries in the area. This rate is divided into a daily rate and the providers paid based on that. An attempt is made to maximize the series of days worked to four or more at once to ensure continuity.

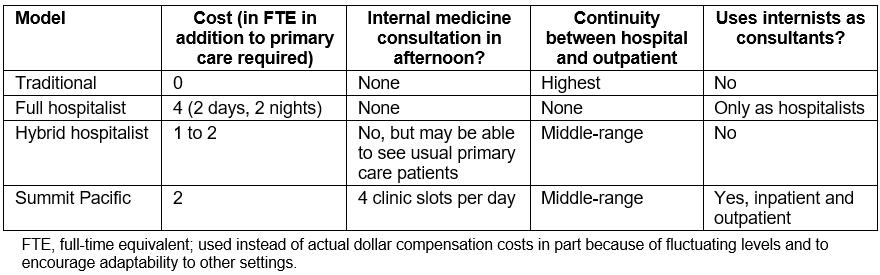

One can compare the model to the traditional primary care model and the full hospitalist models as noted in Table 1. The traditional model refers to the model that existed in Summit Pacific prior to the move to the new location, which was most prevalent in the USA prior to the hospitalist movement. In this model, the PCP sees his or her own patients in the hospital and shares a call schedule with other PCPs.

Several other elements of the model potentially contribute to cost savings. The internists see patients in the clinic, thus generating revenue above only inpatient work. The internists do procedures that other providers, such as those staffed by hospitalist agencies for this size hospital, typically do not do. These include central lines, treadmills, paracentesis, and thoracentesis. Having the internist on-site contributes to many improvements at no additional cost, such as EKG over-read for the clinics, spirometry interpretation, curbside consultation, and ER consultation.

The costs may still be more than the traditional model without factoring in length of stay and other such measures. In addition, the use of general internists as consultants in selective cases may serve as a cost-containment measure for the healthcare system as a whole.

Table 1: Comparison of three inpatient provider staffing models

Discussion

Medical work in a rural setting in the USA has evolved to the point of being uncomfortable for, and unfamiliar to, many providers trained in urban areas. A specific rural health specialty has been proposed but does not yet exist11. Actions such as Missouri’s approval of semi-independent practice by medical school graduates without residency or even internship12 illustrate the sense of desperation on the part of rural communities to attract providers.

Rural patients often travel very long distances for specialty care13. Reducing the number of trips may reduce this burden on patients. Providers, for multiple reasons, frequently refer patients to subspecialists at the patient’s request, knowing that there is no medical reason to do so14. Large proportions of rural Indian clinic providers in Montana and New Mexico reported difficulty in referring patients to numerous specialist types15.

Increasing and ensuring quality in medical care while containing costs is a great challenge. Despite increased spending, mortality in middle-aged white Americans has actually increased between 1999 and 201316. An increased number of PCPs in a community has been associated with reduced mortality and improvements in various health measures in multiple studies17. The Summit Pacific model potentially provides a way for PCPs to reduce referrals to outside facilities and to subspecialists in a safe and manageable way.

Attracting PCPs to rural areas is difficult. The Summit Pacific model provides reduced on-call duties to the PCPs and increased access to specialist consultation. These factors were referenced in surveys in Ontario18 and New Zealand19 as solutions that would help retain rural physicians.

The traditional model costs the least, and ensures the most continuity of care. There are many good reasons to maintain it or components thereof if possible20. However, half of the internal medicine physicians in the USA are now hospitalists4. It has been reported that rural communities already use a variety of methods for inpatient staffing, and often do not follow an exact hospitalist or traditional model21. This suggests that looking for creative in-between models may benefit rural communities.

The largest competing model is the full hospitalist model described above. Financial, social, and regulatory factors have contributed to this model being very appealing despite its high cost. In a rural setting, the relative costs of this model are increased even more. The practitioner is paid more and sees fewer patients than any of the other models. This ‘paying the doctor to not work’ may lead to decreased proficiency and skill in caring for patients at all. If rural hospitals adopt this model, it may lead to decline in actual quality of care, and contribute to further small town hospital closures.

The ‘hybrid rotating hospitalist’ model has many similarities in costs and advantages to the Summit Pacific model. The main problem with setting this up is that, as mentioned, the internal medicine primary care force has already largely jumped ship to become full-time hospitalists or outpatient doctors, whereas typically the hybrid model starts by using providers already participating in a traditional model. In the Summit Pacific model, all the internists were already in full hospitalist or outpatient-only models, but were able to incorporate into this rural healthcare model nonetheless.

Conclusion

A model for internal medicine staffing of a small town hospital in the USA, described in this article, has been functioning successfully for over 3 years. It potentially reduces costs to the hospital by 50%. It also potentially reduces unnecessary consultations, helps recruit and retain physicians to smaller communities, and may increase satisfaction for patients and providers. It may be a way to help bring the modern internist back to the small town medical system. Other small hospitals are encouraged to investigate whether this staffing model or components thereof might be useful in their setting.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Dr Richard Sams, Dr John Butler, and Dr Ki Shin for assistance, advice, and feedback. Also special thanks to Renee Jensen, CEO, Summit Pacific Medical Center, and the excellent staff working there.