full article:

Introduction

Approximately one-third (28.7%) of Australia’s population lives in regional or remote areas1, but only 15% of medical specialists are employed in these areas2. These figures may under-represent the true shortage of specialists in rural areas, which has been obscured by a heavy reliance on locums and internationally recruited medical specialists. Shortages of specialists in rural areas result in service gaps, which may have serious consequences for the health of local people3. With an ageing rural medical workforce4, and increasing specialisation, the problem of maldistribution of the specialist workforce is a pressing issue.

According to data from the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency, 247 medical specialists are working in Tasmania3. There are no publications describing the distribution of this workforce within Tasmania. However, there are anecdotal reports of workforce saturation in Hobart and shortages of specialists in the north and north-west of the state. Like many rural areas, the health service where this research was conducted has struggled to attract and retain medical specialists. There are local reports of an increasing reliance on international medical graduates and locums to fill positions, and as for other areas of rural Australia there is concern about service gaps. Given the scant literature in this area, the present study aimed to describe the factors that contribute to specialist workforce retention and attrition within a regional health service.

Methods

Following ethics committee approval, currently employed specialists in the health service (‘stayers’) were emailed an invitation to participate in the research. Specialists who had left the service (‘leavers’) were identified through the payroll office, with current email addresses identified for 93 leavers. Two were returned to sender as ‘addressee unknown’, three specialists replied declining to participate and eight accepted the invitation. This indicates a 9% response rate, although it is likely that a substantial proportion of the invitation emails were not received or read by recipients. Twenty-two interviews were conducted: 12 with stayers, eight with specialists who had left the service and two with specialists who intended to resign.

The interview guide was developed according to the themes identified by May et al in a study of general practitioner and specialist recruitment and retention in regional New South Wales5. All interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed verbatim and imported into QSR NVivo v10 (QSR International; https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/home) for thematic analysis. Transcripts were coded according to the themes noted by May et al, with emergent themes also identified. Responses were grouped into three main domains: professional factors, location factors and social factors5. The data were then investigated by comparing stayers and leavers (or those with intentions to leave).

Ethics approval

The University of Tasmania Human Research Ethics Committee reviewed the research proposal and granted ethics approval for the study (reference H16051).

Results

The 22 interview participants were specialists in emergency medicine (6), anaesthetics (4), general medicine (2), paediatrics (2), psychiatry (2), orthopaedic surgery (2), general surgery (1), geriatric medicine (1), palliative care (1) and urogynaecology (1).

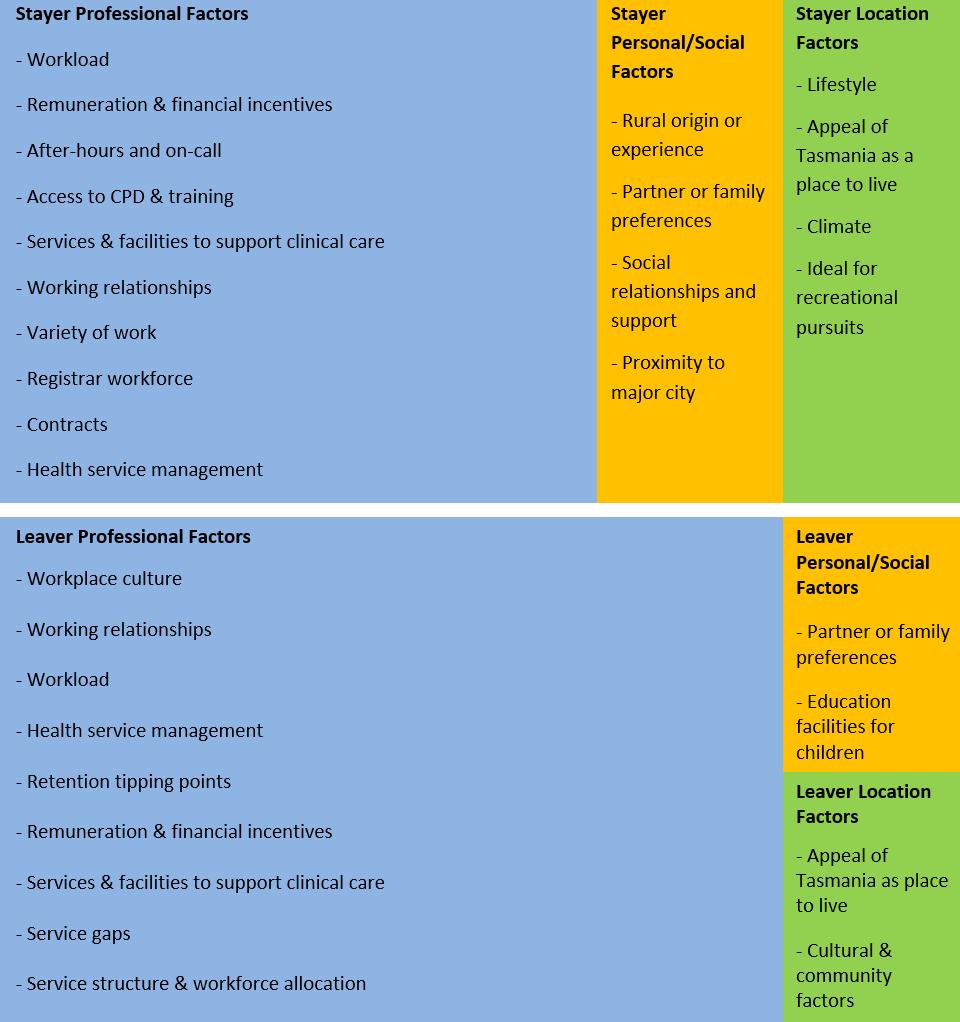

While professional factors played a dominant role in the retention decisions of both stayers and leavers, they had considerably greater salience for leavers, as evidenced by the thematic maps (Fig1).

Figure 1: Main themes and quantity of comments coded to main themes among stayers and leavers.

Figure 1: Main themes and quantity of comments coded to main themes among stayers and leavers.

Professional factors influencing specialist workforce retention

After-hours/on-call work: The most common theme discussed by all participants was on-call work, with a diverse range of perspectives on this topic. Stayers and leavers made positive and negative comments. However, for a small number of specialists who described their commitments as particularly arduous, this was a significant cause of job dissatisfaction and a contributing factor to their decision to leave.

Some specialists commented that their on-call workload was easily manageable due to senior registrar support, while others noted that the absence of senior registrars in their specialty made their on-call commitments particularly taxing.

Specialists in both groups recognised that the on-call workload was inevitable due to the small size of the service and lack of critical mass to enable a sustainable on-call roster.

Workload: Workload (eg usual working hours) was the second most common theme. There was a wide spectrum of perspectives on this topic. Some participants noted that their working hours were comparable to those of other regional centres, some noted that their working hours were favourable to regional centres and others noted that their working hours were considerably longer. Despite some specialists describing heavy workloads, autonomy in determining workload was a key factor in work satisfaction. Those who felt they had little control over their workload expressed dissatisfaction, while those who had autonomy noted their heavy workload was due to personal preference. It was noted that historical Visiting Medical Officer contracts limiting the number of working hours resulted in an inequitable workload distribution, with the burden continuing to fall on staff specialists.

Health service management: There was a considerable difference among stayers compared to leavers in their discussion of health service leadership. Five of the 12 stayers and 8 of the 10 leavers discussed this theme. Leavers were more critical of senior health service management. However, many of the comments related to historical events characterised by frequent changes to the staffing of senior management posts. This created a sense that the service was operating in perpetual crisis mode. There was acknowledgement that the tumultuous period of senior health service management had eased. However, there was a continued perception of a fractious relationship between clinicians and senior health service managers.

Some leavers also discussed the need for transparent, competitive, external processes to select leaders. Such a process helps to provide a mandate for effective leadership. It was also recognised that leaders should receive training and appropriate financial remuneration to attract and retain quality leaders.

Teamwork and workplace culture: All 12 stayers and seven leavers discussed the theme of teamwork. Positive and negative comments were made in relation to interactions with nursing staff, although overall hospital nurses were described as ‘very committed’. Comments about teamwork were mainly positive among stayers, although there was a mix of positive and negative comments among the leavers. Non-collegial behaviour was raised by 4 of the 10 leavers. Some locums were described as behaving inappropriately towards specialist colleagues. Additionally, there was the perception of organisational reluctance to address the issue of inappropriate behaviours among locums, with this seen as stemming from difficulties in attracting a locum workforce.

Professional fulfilment: All 12 stayers but only 3 of the 10 leavers made comments on professional fulfilment. Providing treatment and care to sick patients was fundamental to professional satisfaction. However, there was also recognition that feeling valued by the health service was an important source of professional fulfilment, and a factor in deciding to remain working in the service.

Half of the participants in each group discussed the importance of work variety in contributing to their professional satisfaction. The rural setting was recognised as providing an opportunity for generalist work, while the unique population and socioeconomic status of the area resulted in interesting clinical cases. Additionally, the opportunity to establish new services was pivotal to job satisfaction for two participants.

Professional isolation is a subtheme of professional fulfilment discussed by four stayers and four leavers. It was suggested that the absence of a local specialist network for advice and support is a significant contributor to work-related stress. It was also noted that connecting with peers within the state and interstate is fundamental to managing stress arising from professional isolation. However, metropolitan specialists were sometimes seen as reluctant to provide support.

Registrar workforce: Stayers and leavers recognised the importance of the registrar workforce for maintaining the quality of the service. Perceptions of the standard of registrars varied across the specialities: some registrars were senior and highly skilled, while others were described as junior and of lower standard compared to those in metropolitan centres. There were concerns that the teaching and support provided to registrars needed to improve. The locum workforce and the lack of support from metropolitan colleagues in preparing registrars for exams were also identified as barriers to the provision of quality supervision to registrars. Some leavers noted that the loss of specialist college accreditation for trainees was a ‘red light warning flag’ indicating wider systemic problems within the hospital.

Model of practice: Most stayers and leavers commented that they preferred the generalist model of specialist practice, rather than a subspecialty. However, for some specialists, their career preference for subspecialisation was abandoned due to personal factors that kept them living in the area. Some leavers commented that they preferred working as a subspecialist; however, the health service required a generalist role. Two leavers noted that the health service was inflexible towards their subspecialty preferences, so they sought a permanent position interstate.

Professional development: Accessing continuing professional development (CPD), training courses and conferences was a main theme, although there was greater discussion on this theme among the stayers. There was common acknowledgement of the need for additional professional development leave days to compensate for the extra day of travel required for departure from and arrival back to the region when attending interstate and international events. There was also consensus that funding allocated for professional development should be increased in consideration of the higher costs associated with travelling from a rural location. Increased CPD leave and funding were noted as particularly important for helping to alleviate professional isolation and improving specialist retention.

Employment contracts: Participants were critical of the inequity across the state in the provision of permanent contracts, which is a legacy of the state having three separate health organisations previously. While most were not concerned about their lack of a permanent contract, it was noted that, for some specialists, a permanent contract provides reassurance and a feeling of being valued.

Remuneration and financial incentives were discussed by 9 of the 12 stayers and 8 of the 10 leavers. Participants felt that the pay scale in the service was lower than that of metropolitan centres and regional areas in other states, with interstate colleagues estimated to earn three times the salary paid locally. A few participants suggested that their overall remuneration was similar to that of consultants in other states, although this was not taking into account on-call hours, which, when factored in, considerably reduced their hourly rate. For approximately half the group, this was not considered important for their overall contentment or when making decisions about where to work.

Personal and location factors influencing specialist workforce retention

The main personal factors that influenced specialists’ decisions to stay working and living in the area were rural origin or experience, family or social connections within the area, lifestyle, a desire to maintain location stability for children and a preference for rural living.

Ten of the 12 stayers either grew up in a rural area or had extensive rural workplace experiences prior to arriving in the area. While most of the leavers also had rural workplace experience, only three were of rural origin. Two participants, both long-time stayers, grew up in the area and stated that they had strong desire to return to their families and local communities after completing their specialist training.

The nine stayers who discussed lifestyle spoke positively about the ease of living in the area, the ability to achieve a healthy work–life balance, the relaxed pace of life, low traffic volumes, the friendly community, a scenic environment and access to both the coast and mountains.

Tipping points

Six of the 10 leavers discussed professional tipping points relating to their decision to leave. These included excessive on-call workloads, difficult relationships with other specialists, unreasonable demands and managerial styles of historical health service leaders, the appeal of a challenging position interstate, fear of not being able to secure a position in a metropolitan hospital in the future, family pressure to live in a metropolitan area and concerns for patient safety. Resignations were also timed to fit with family preferences for children to attend private schools in metropolitan areas.

Family preference to live in an urban area was the overriding factor that led to two overseas-trained specialists leaving. Both of these participants were content working in the health service but social isolation experienced by their families resulted in a decision to leave.

Discussion

The present study’s findings corroborate previous research that identified professional factors as dominating retention decision-making5-8. Secondary considerations relating to personal and location factors played a greater role in decision-making among stayers compared to leavers. This was evidenced by the thematic maps, indicating the low importance of personal or location factors among those who were unhappy in the professional sphere. Some of the professional factors that contributed to specialists leaving are non-modifiable, such as personality clashes, while related factors, such as the collegial environment, are modifiable.

Onerous work demands, particularly on-call, resulted in exhaustion and burnout, and were an impetus to leave the service for some specialists. This finding is similar to that of Humphreys et al6 who found on-call arrangements were the most significant factor overall in rural general practitioner retention, regardless of location. Excessive on-call demands are not unique to rural Tasmania, as May et al’s recent research in regional New South Wales also reported that after-hours work demands were among the top three professional factors that influence rural specialist retention5.

It is notable that 17 years have passed since the research of Humphreys et al was published6. This indicates that there has been a lack of significant progress on reducing the burden of on-call work among rural specialists. The failure to address this issue reflects a lack of critical mass to cover rosters, and limited financial resources available for locum cover.

There was recognition that excessive on-call demands were a result of the small hospital environment, where a lack of critical mass impacted on-call rosters. To prevent burnout, it is imperative that an adequate number of senior specialists are employed to cover the roster without placing excessive workload demands on individuals. The authors agree with Humphreys et al that a strategic, long-term solution is required to alleviate the pressure of on-call demands6.

The findings also emphasise the importance of autonomy in determining on-call workloads. Those who achieved autonomy were able to find the appropriate balance to suit their preferred way of working and tended to stay in the service. Specialists were appreciative of recent efforts to allocate on-calls to locums. Continuation of this informal policy is crucial to retain specialists with a recognition of the higher threshold of on-call expected by recently fellowed specialists.

The present research found difficult relationships among specialists were a strong contributing factor to the decision of some specialists to leave the service. There is good evidence that positive cultures within hospitals promote staff retention7-11. The present study’s finding is similar to that of May et al5, where workplace culture was the third most important factor in specialist retention in rural New South Wales. It is important to note that a single person’s behaviour can have a disproportionate impact upon teams in a small hospital, while the impact of the individual is diluted in a larger hospital. Given the importance of harmonious collegial relationships within small hospitals, a zero-tolerance policy for bad behaviour is vital, as are clearly defined mechanisms for escalating and managing complaints.

Much of the criticism of health service management expressed by specialists related to historical events and periods of high turnover of health service leaders. Previous research indicates a 26% two-year turnover rate among Swedish health service managers and 40% within 4 years12. Burnout, excessive workloads, lower levels of job control, an inability to ensure quality patient care, insufficient resources and clinical workloads are associated with turnover12,13. Additionally, a systematic review of nurse manager turnover found organisational values/culture, human/fiscal resources and organisational commitment were commonly reported organisational reasons for manager turnover14.

It should also be noted that the interface between clinicians and managers is often a vexed one, with both groups perceiving themselves at odds with the other group. There is a long history of challenging relationships within this arena, with clinician–senior health service manager conflict prevalent across the globe15-19. Tensions between clinicians and service managers observed by participants in this research are a local version of the global issue of autonomy versus accountability. Open dialogue between senior health service managers and clinicians, improved understanding, mutual respect, transparency around organisational change decisions and transparency in resource allocation may improve relationships15-19.

Financial remuneration was not a primary factor in retention decision-making. However, there was acknowledgement that health services have a responsibility to ensure equitable pay scales. Flexible employment contracts, including statewide positions, rural bonuses, flexible leave arrangements and financial incentives for efficiency and performance, were also suggested as ways to improve retention. The implementation of such flexible contracts offering efficiency incentives is inhibited by the health services award and employment law. However, despite these potential limitations, specialist feedback should be sought, with the aim of increasing flexibility and improving retention.

There is a need to review CPD funding and training leave entitlements for specialists in rural areas. Increasing CPD payments and leave entitlements for rural specialists would improve the equity of CPD opportunities and help to reduce specialist isolation. The recently introduced Commonwealth Support for Rural Specialists in Australia Program provides individual grants for rural and remote specialists to participate in CPD training.

The current absence of senior registrars in most specialities had a negative impact on on-call workloads. Increased funding is needed to expand the number of advanced trainees in rural areas and ensure that rural hospitals have access to the highest calibre registrars. Rotation of senior registrars throughout Tasmania would alleviate pressure on rural specialists and reduce costs associated with locum positions. Support for training requires support for clinical supervision, funding for posts and generation and de-stigmatisation of rural training. This requires national effort.

Given the fact that all of the specialists needed to elect to come to the area, or to come back to the area after training, the importance of professional satisfaction in their decision to stay was heightened. This has repercussions for the health service, as satisfaction with their work environment is pivotal to retention decision-making.

Specialists who stayed in the area developed strong social connections within the region, through their children, community groups or recreational pursuits. As most specialists who move to the area do not have a pre-existing social connection to the area, it is important for the health service to organise socialising opportunities and provide social support to specialists and their families. It is also imperative to provide medical care for family members of overseas-trained specialists. For some overseas-trained specialists, a feeling of social isolation among their family members was the primary motivation for leaving the service.

The study was limited by its small sample size and low response rate among leavers, which limits generalisability. Additionally, some of the issues discussed were historical and had already been resolved, at organisational level, by the time of interview. The recruitment of stayers and leavers was designed to avoid a sample biased towards either negative or positive experiences. However, it is possible that findings are skewed towards disaffected leavers.

Conclusion

Specialists who had rural backgrounds, who established strong personal connections in the area and those who had a preference for rural living were more likely to stay. However, professional factors dominated retention decision-making. The importance of professional factors, which has been identified previously, is critical – whilst there were clear issues such as heavy on-call demands, the responses of participants to these challenges were not uniform. This research underscores the importance of flexibility and autonomy in workload determination, and equity with interstate and intrastate contractual conditions and pay scales. Efforts to reduce specialist isolation and increase senior registrar rotations may reduce specialist turnover. A zero-tolerance policy for bad behaviour should also be adopted and enforced. It is crucially important for services to monitor specialist workforce turnover to identify and address issues within the workplace that create tipping points for specialists. Exit interviews and access to accurate electronic human resources data are essential to prevent high rates of specialist turnover in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the specialists who kindly devoted their time and shared their experiences and perspectives during the study interviews.

references:

You might also be interested in:

2020 - Fluvial family health: work process of teams in riverside communities of the Brazilian Amazon

2010 - Analysis of enhanced pharmacy services in rural community pharmacies in Western Australia