full article:

Introduction

Indigenous peoples in Canada and worldwide experience widespread social, political, economic and health related inequities relative to non-Indigenous populations1. Within the North American context, the European invasion during the 16th century negatively impacted Indigenous populations with the introduction of infectious diseases and colonial legislation, practices, and narratives that were intended to forcibly assimilate and demoralize diverse groups of Indigenous peoples2,3. Under the auspices of the Indian Act 1876 in Canada, Indian residential and day schools were federally ordained and operated from 1883 to 1996. The residential and day school system forced Indigenous children and communities to be ‘civilized’ within a Euro-Christian cultural paradigm. In these contexts, Indigenous peoples experienced varying forms of abuse that included verbal, physical and sexual abuse, as well as an overwhelming loss of language, culture, identity, community, and connection to the land3. Residential and day schools have devastated generations of communities through the effects of intergenerational trauma, grief, and loss. Continued marginalization, discrimination, and oppression of Indigenous peoples, both within and outside of the healthcare system, have perpetuated the legacy of colonization into the present day4.

While pervasive disparities exist among Indigenous populations relative to non-Indigenous populations across all domains of health, mental wellbeing is perhaps the most heavily affected outcome of intergenerational and collective trauma experienced by Indigenous peoples, stemming from colonialist and racist agendas5. In Canada, this is evidenced by high rates of problematic substance use, addiction, suicide, and violence6,7. Additionally, children with parents or grandparents who attended residential schools report higher levels of depressive symptoms related to chronic stressors, relative to children who did not have a parent or grandparent who attended residential school8. Similarly, a recent Australian study by Nasir and colleagues9 found more than a three-fold elevated rate of mood disorders and substance use disorders, and more than a two-fold elevated rate of any mental health disorder amongst Indigenous peoples of Australia relative to non-Indigenous Australians. Until recent years, research involving Indigenous peoples has often excluded Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing, which often led to harmful consequences and ultimately widened the heath equity gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations10-12.

Rates of suicide are disproportionately higher among First Nations, Métis and Inuit (FNMI) youth relative to non-FNMI youth in Canada13. Importantly, however, suicide rates have been found to vary across some First Nations communities depending on the extent of cultural continuity14. Cultural continuity reflects the transmission of culture and the knowledge, traditions, and language that defines one’s culture, and is operationalized through different levels of self-governance and community control over resources and services15. As such, many Indigenous communities that were able to retain and/or restore their culture despite the effects of colonialism appear to have lower rates of suicide, suggesting that culture may serve as a protective factor.

Experts have argued that Indigenous leadership, knowledge systems, beliefs, and practices are essential for the development and implementation of culturally safe and successful initiatives to improve Indigenous peoples’ health16. However, knowledge has not been synthesized on Indigenous mental wellness initiatives. In this article, the term mental wellness is used in a holistic sense that includes a balance between physical, spiritual, mental, and emotional health which, in Indigenous contexts, is often also connected to connections with creation and culture17. While evaluation research provides important information regarding the effectiveness of mental wellness initiatives, this research needs to be synthesized to delineate the different types of evaluation tools and strategies that are being used and the appropriateness of these approaches to evaluation within Indigenous communities18,19. To address these gaps in knowledge, the authors conducted a scoping review to characterize Indigenous community-based mental wellness initiatives and their approaches towards evaluation.

Specifically, this scoping review aimed to address the following questions:

- Among Indigenous communities in Canada, the USA, Australia, and New Zealand, what were the characteristics of community-based mental wellness initiatives that have been evaluated?

-

Among those community-based mental wellness initiatives that were evaluated:

- what were the (a) types of evaluations that were conducted, (b) specific measures and/or indicators that were assessed, and (c) measurement tools, instruments and/or scales that were used?

- what were the different types of community involvement during the development, implementation, and evaluation stages?

- what were identified as challenges and recommendations by the authors with respect to the development, implementation, and evaluation of these initiatives?

The authors of this review are three First Nations researchers (NTGG, RL, NG) and four non-Indigenous health researchers (JV, MEMN, LP, SW), three of whom have extensive experience working closely with Indigenous communities in Canada.

Methods

This review is based on guidelines from the Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual20 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses – Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR)21. An unpublished protocol, detailing the different types of informational sources, specific search strategy and data extraction procedures, was developed to guide the conduct of this review.

Eligibility criteria

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were used:

- The study must explicitly focus on Indigenous peoples and their communities from USA, Canada, Australia or New Zealand. Indigenous populations from these countries have shared, yet distinct, histories of colonization by European settler populations. Indigenous study participants of all age groups were considered for this review.

- The study focuses on a community-based mental wellness initiative – a strategy, service, or program. The initiative must focus explicitly on addressing mental health or wellness at the community level as a primary objective. Initiatives may range from long-term programs with sustained funding to those that may be more one-off health promotional campaigns. We use the term mental wellness to include a wide range of concepts ranging from cultural connections and pride, self-esteem, and resilience to coping and managing stress. For the purposes of this review, the term community is restricted to geographically and/or politically bound Indigenous communities, predominantly rural and remote Indigenous communities. As such, studies concerning urban Indigenous populations were excluded.

- The mental wellness initiatives demonstrated Indigenous community involvement. Included studies must demonstrate evidence to suggest they were in alignment with guidelines such as or similar to the Tri-Council Policy Statement-2 (TCPS-2)22:

a process that establishes interaction between a researcher or research team, and the Aboriginal community relevant to the research project. It signifies a collaborative relationship between researchers and communities, although the degree of collaboration may vary depending on the community context and the nature of the research. The engagement may take many forms including review and approval from formal leadership to conduct research in the community, joint planning with a responsible agency, commitment to a partnership formalized in a research agreement, or dialogue with an advisory group expert in the customs governing the knowledge being sought. The engagement may range from information sharing to active participation and collaboration, to empowerment and shared leadership of the research project. Communities may also choose not to engage actively in a research project, but simply to acknowledge it and register no objection to it.

- The study must describe the implemented community-based mental wellness initiative and report on how the initiative was evaluated. Included studies must sufficiently report on applicable methods for evaluation of outcomes and/or process-related elements. This may include, but is not limited to, interviews, focus groups, pre- and post-interventional change scores in health status, behavior, and awareness.

- The article must be published between 2008 and June 2018, in English. This review was restricted to a 10-year period to capture published and non-published work that would align more closely with recently established guidelines and ethical principles for research involving Indigenous peoples (such as the TCPS2 in Canada and the AIATSIS Guidelines for Ethical Research in Australian Indigenous Studies).

All article types were considered, including original research, reports, program evaluations, clinical trials, amongst others. Although literature and systematic reviews were excluded, reference lists within these reviews were scanned for eligible articles.

Search strategy

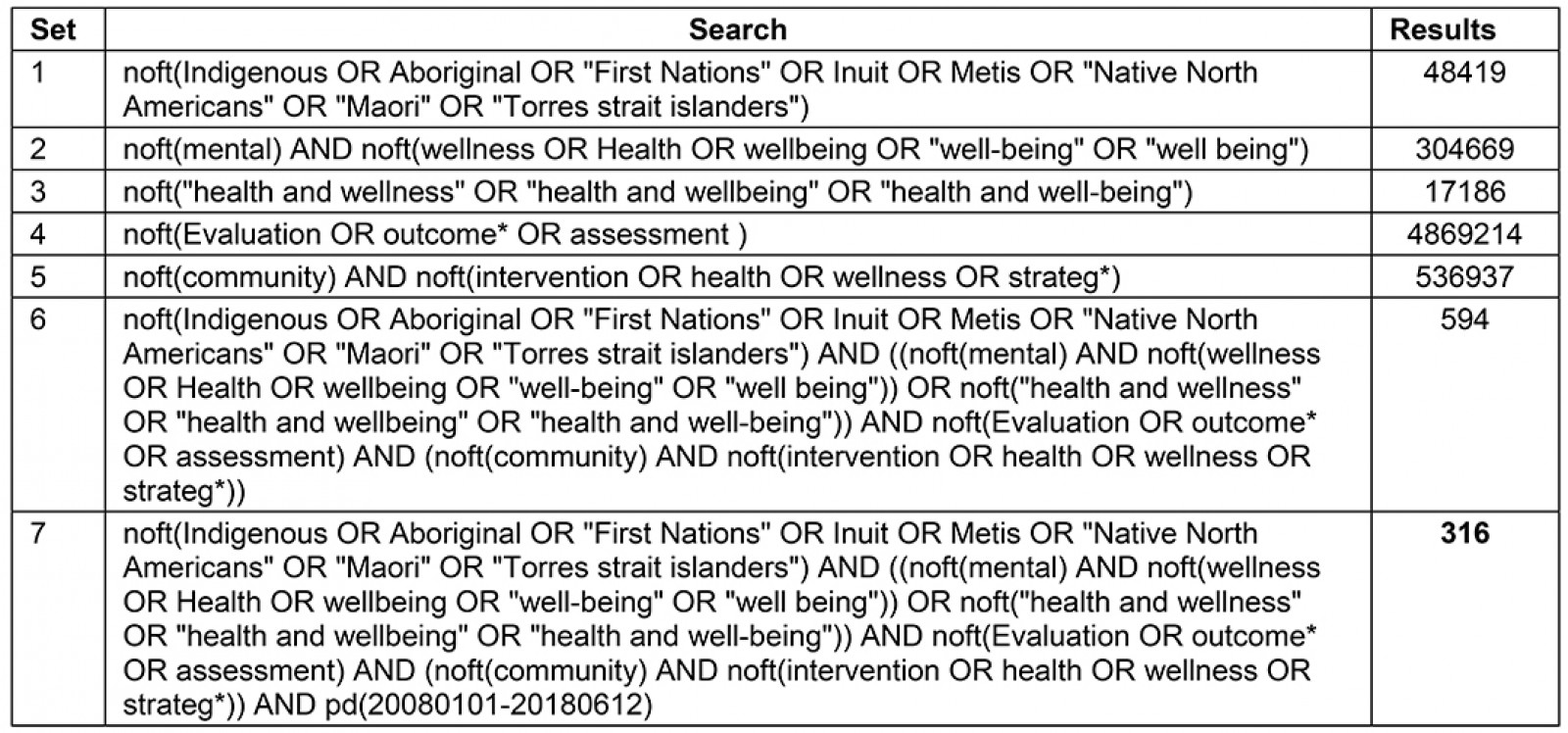

A comprehensive search, including both published and grey literature sources, was conducted to include articles from 1 January 2008 to 12 June 2018. Indexed and non-indexed databases were searched to identify published work, which included PsychINFO, Medline, CINAHL, Web of Science, Aboriginal Health Abstract Database, Bibliography of Native North Americans, Circumpolar Health Bibliographic Database, Dissertation Abstracts, First Nations Periodical Index, National Indigenous Studies Portal, ProQuest Conference Papers Index, Social Services Abstracts, and Social Work Abstracts. The following search terms were mapped on to relevant medical subject headings (MeSH) and combined using Boolean operators (when such algorithms were permitted): community; health; wellness; strategy; Indigenous; Aboriginal; First Nation; Métis; Inuit; American Indian; Native American; Torres Strait Islander; Maori; program; intervention; prevention; treatment; evaluat*; outcome; impact; effectiveness; mental health; addiction; substance abuse; and depression. Additionally, grey literature documents such as reports from federal, provincial, and territorial governments, health funders, and other organizations within Canada were also retrieved. A librarian with expertise in health research was consulted to inform the development of this search strategy. The complete search strategy for Medline is detailed in Appendix A.

Supplementary table 1: Complete search strategy for Medline (1 January 2008 – 12 June 2018)

Study selection and quality appraisal

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts of retrieved peer-reviewed articles, and one reviewer scanned through the titles of available documents from grey literature sources to identify relevant documents. A spreadsheet template was shared amongst reviewers for data extraction. Three reviewers independently extracted data from included articles, which was verified by a fourth reviewer. The following information was extracted from articles:

-

characteristics of mental wellness initiatives:

- location of strategy (First Nation; band and/or reservation; state, territory/province; and country) and specific population of interest

- specific area of focus within mental wellness, implementation modality (eg educational, skills-based training, culture-based, online) and setting (eg land-based, community-based)

-

approach to evaluation:

- evaluation method (qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods approach)

- specific indicators or measures that were evaluated, and assessment tools and/or scales that were used for their evaluation

- types of community involvement in the development, implementation, and evaluation of mental wellness initiative (specific roles and responsibilities, if reported)

- challenges and recommendations identified by the authors regarding the development, implementation, and evaluation of mental wellness initiative (if reported).

To ensure applicability of research involving Indigenous peoples, the types and levels of community involvement in research for each article were assessed by two authors until consensus was reached, in lieu of a validated quality appraisal tool.

Data analysis and synthesis

Thematic analysis of extracted fields was conducted to identify themes and relevant categories that characterize the breadth of typologies that pertained to the review questions. Two pairs of reviewers were assigned data extraction fields to independently identify an initial set of thematic codes, which was later discussed among a pair of reviewers until consensus was achieved on a final set of thematic codes. Disagreements on identified codes were resolved by consensus among the four reviewers. Studies that discussed each of the identified codes were tallied. Findings from the thematic analysis were tabulated and synthesized narratively.

Ethics approval

This review did not directly involve any primary patient recruitment, and therefore institutional review board approval was neither sought nor required.

Results

Search yield

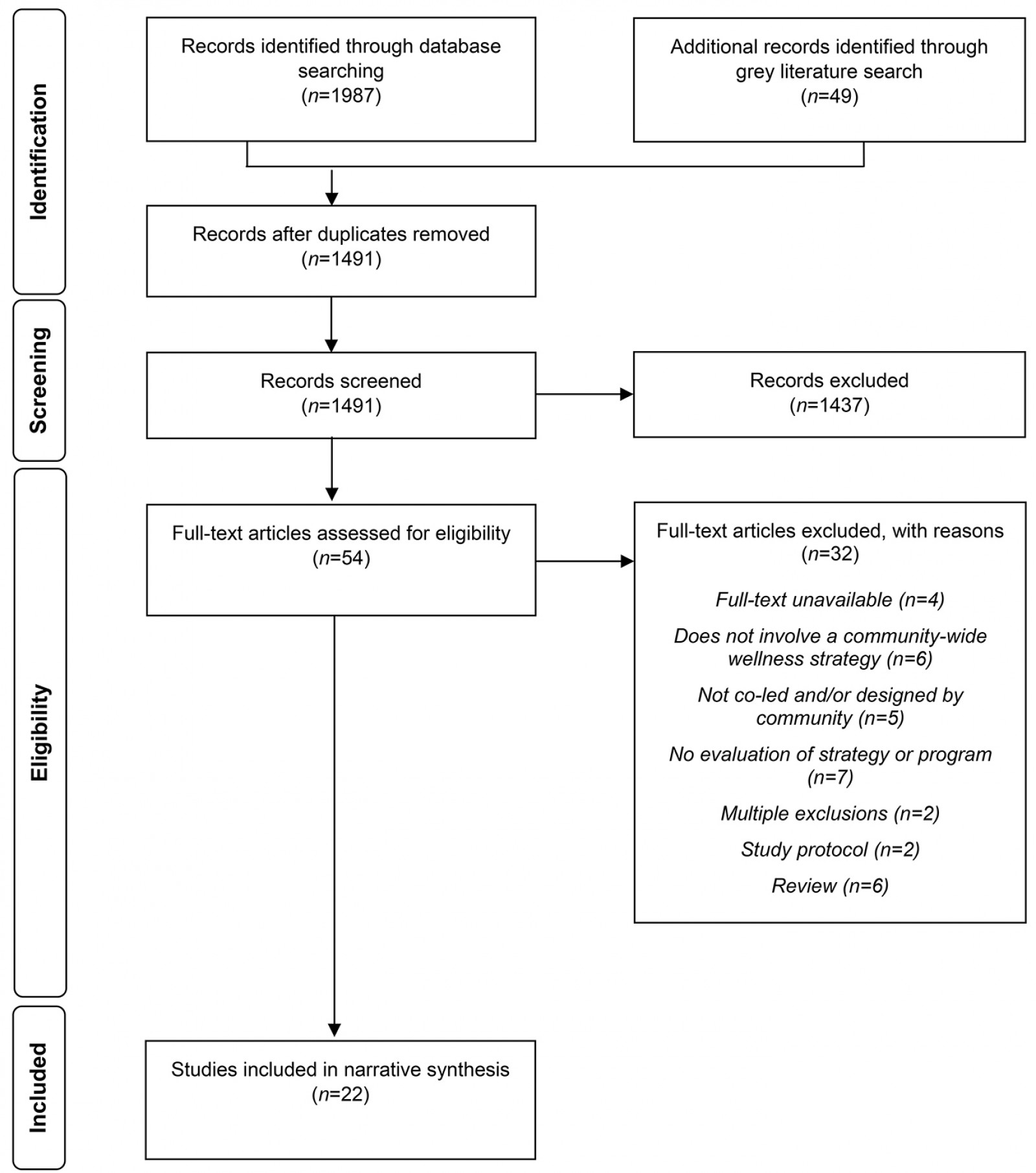

The search resulted in 1491 unique articles across published and grey literature (Fig1). Of these retrieved articles, 22 articles were included based on eligibility criteria. Nineteen articles were obtained from electronic databases, three were identified from literature reviews and systematic reviews, and no relevant papers were identified from the grey literature.

Figure 1: PRISMA flowchart detailing search retrieval and inclusion.

Figure 1: PRISMA flowchart detailing search retrieval and inclusion.

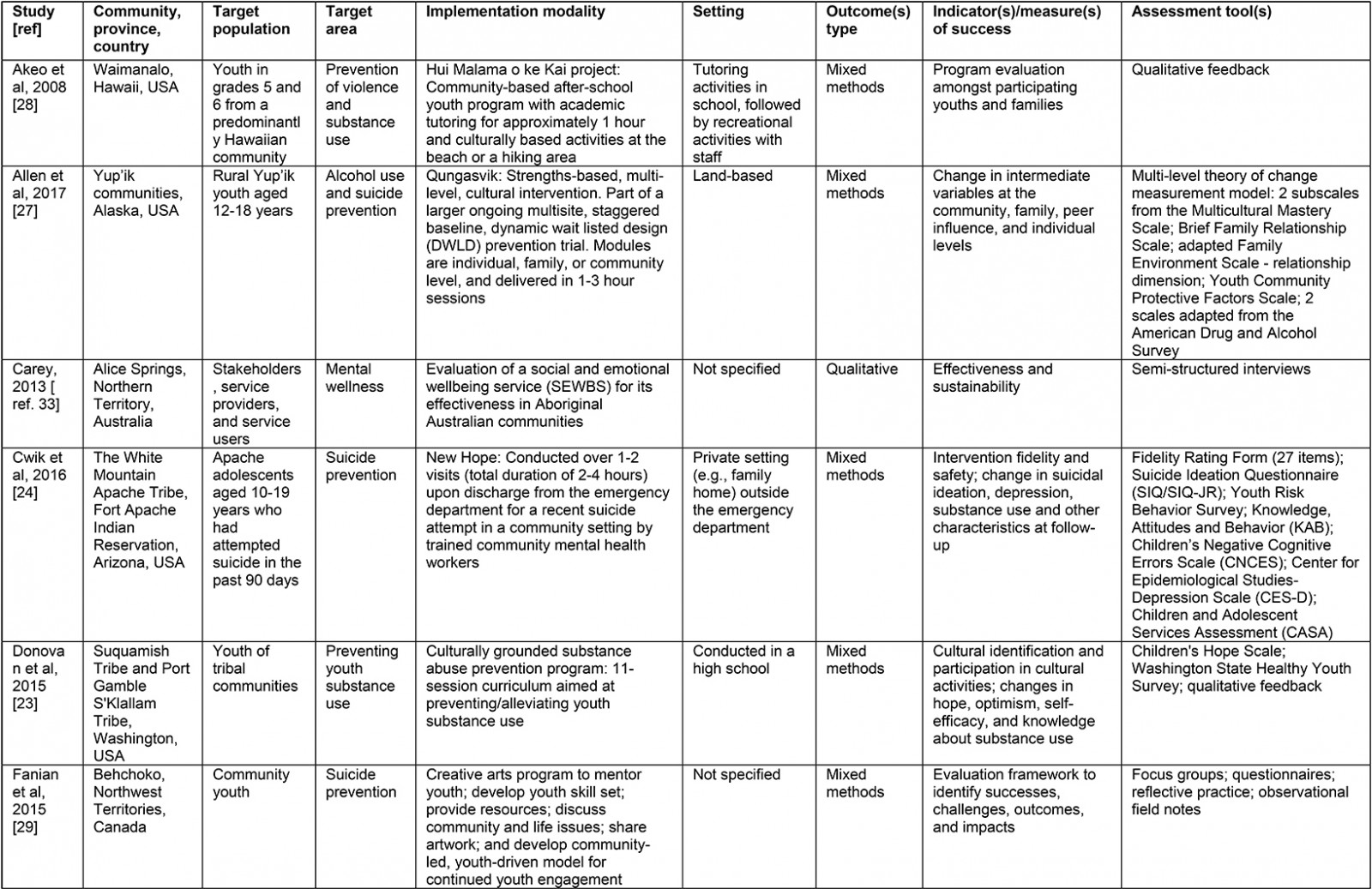

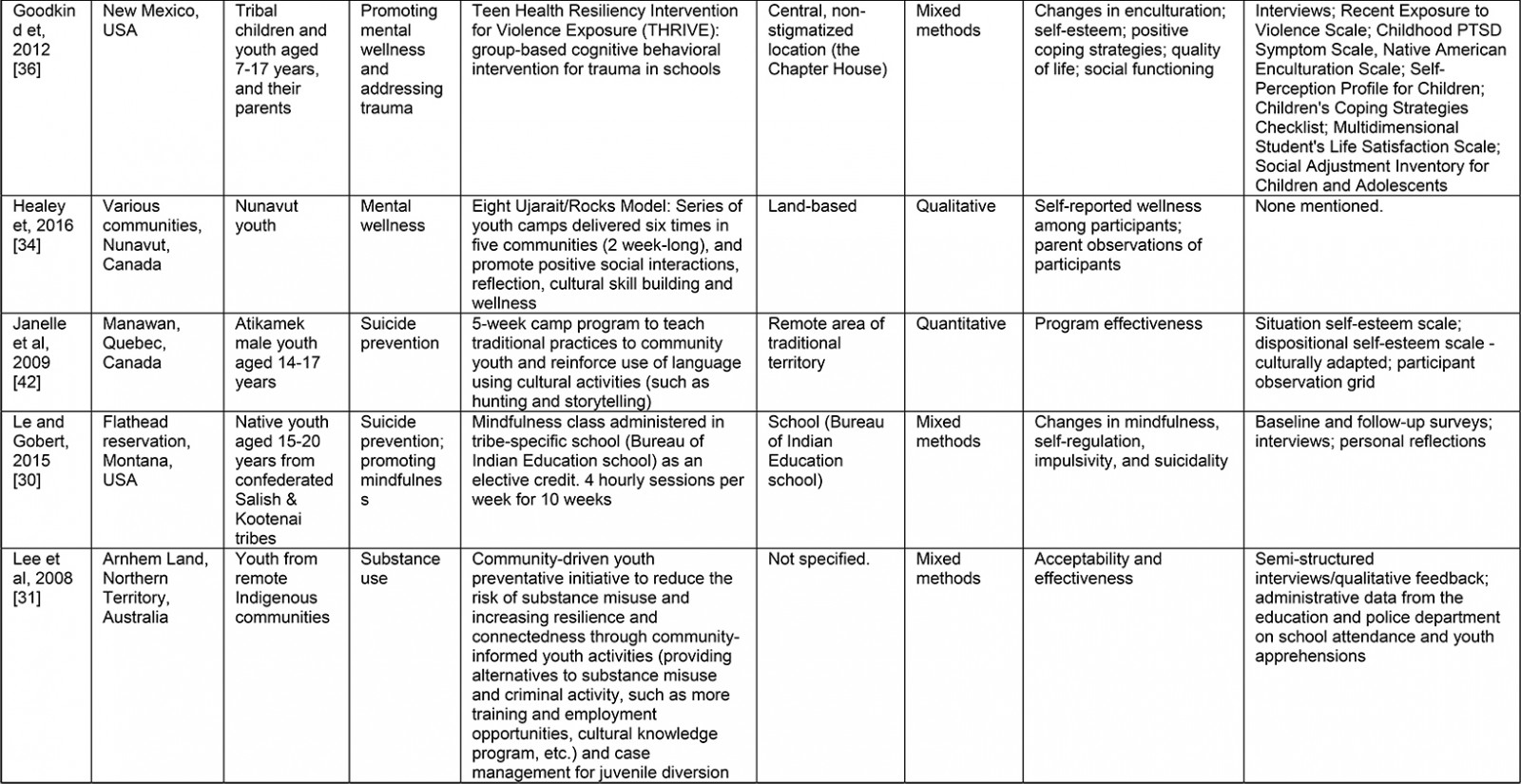

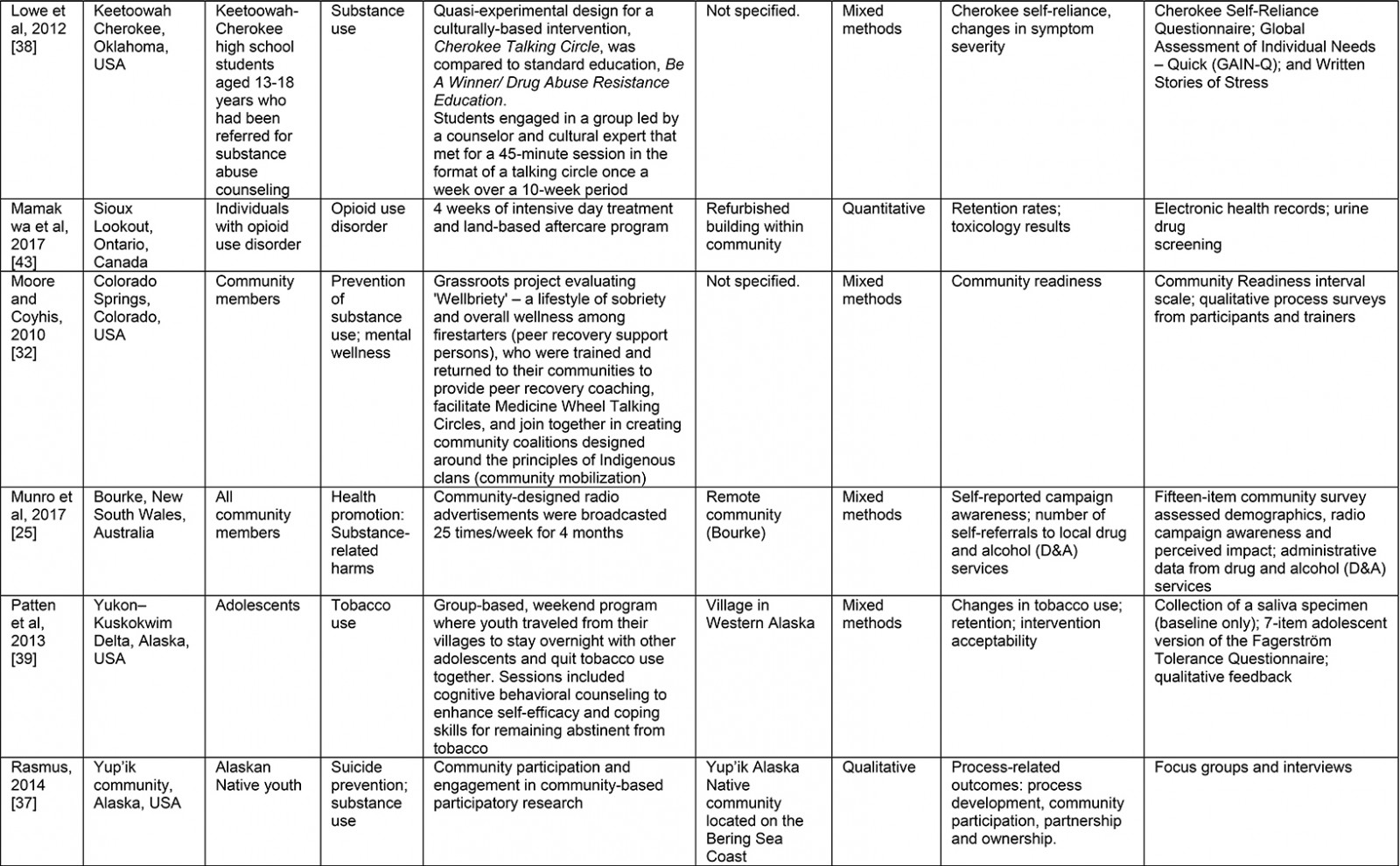

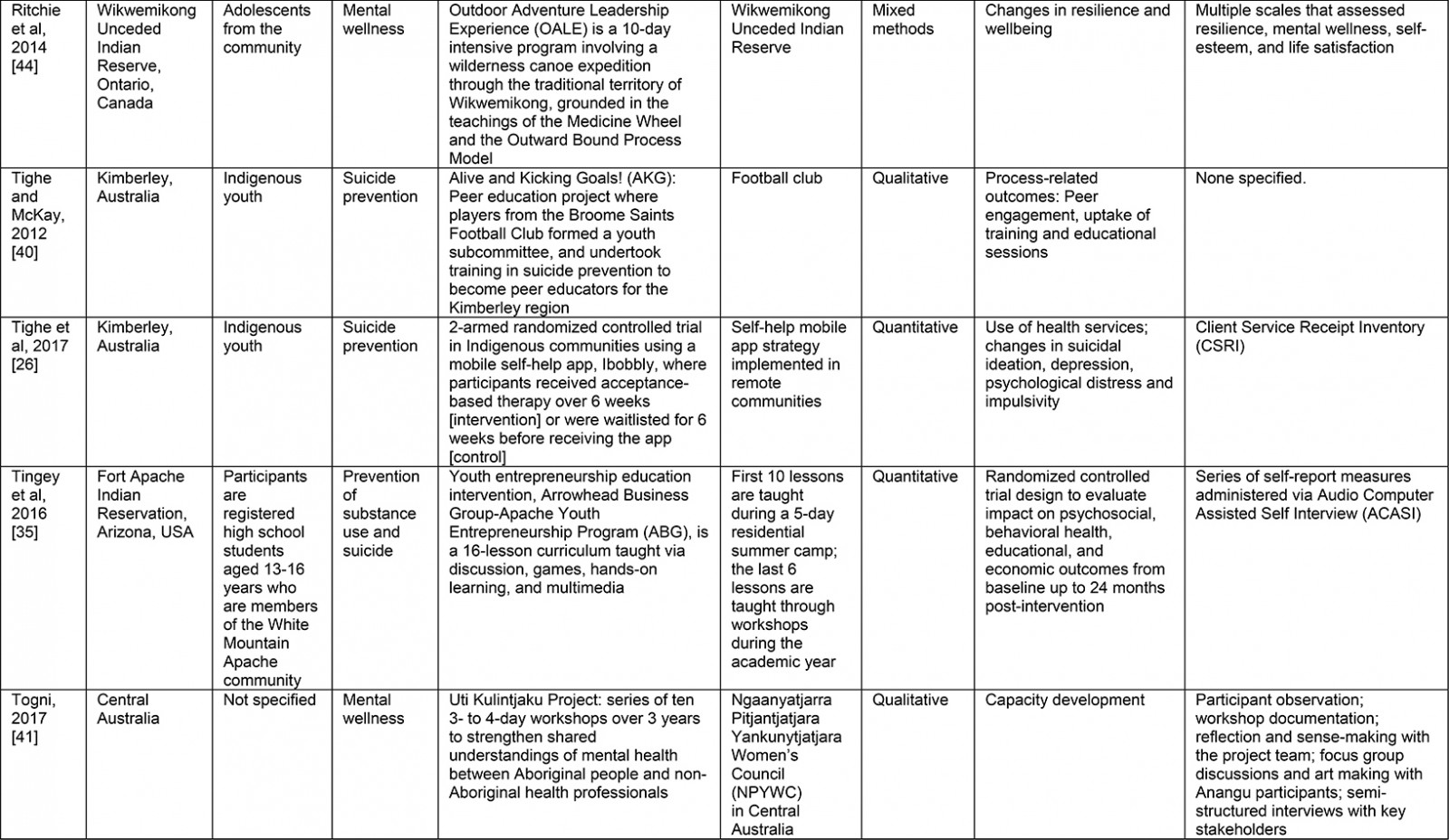

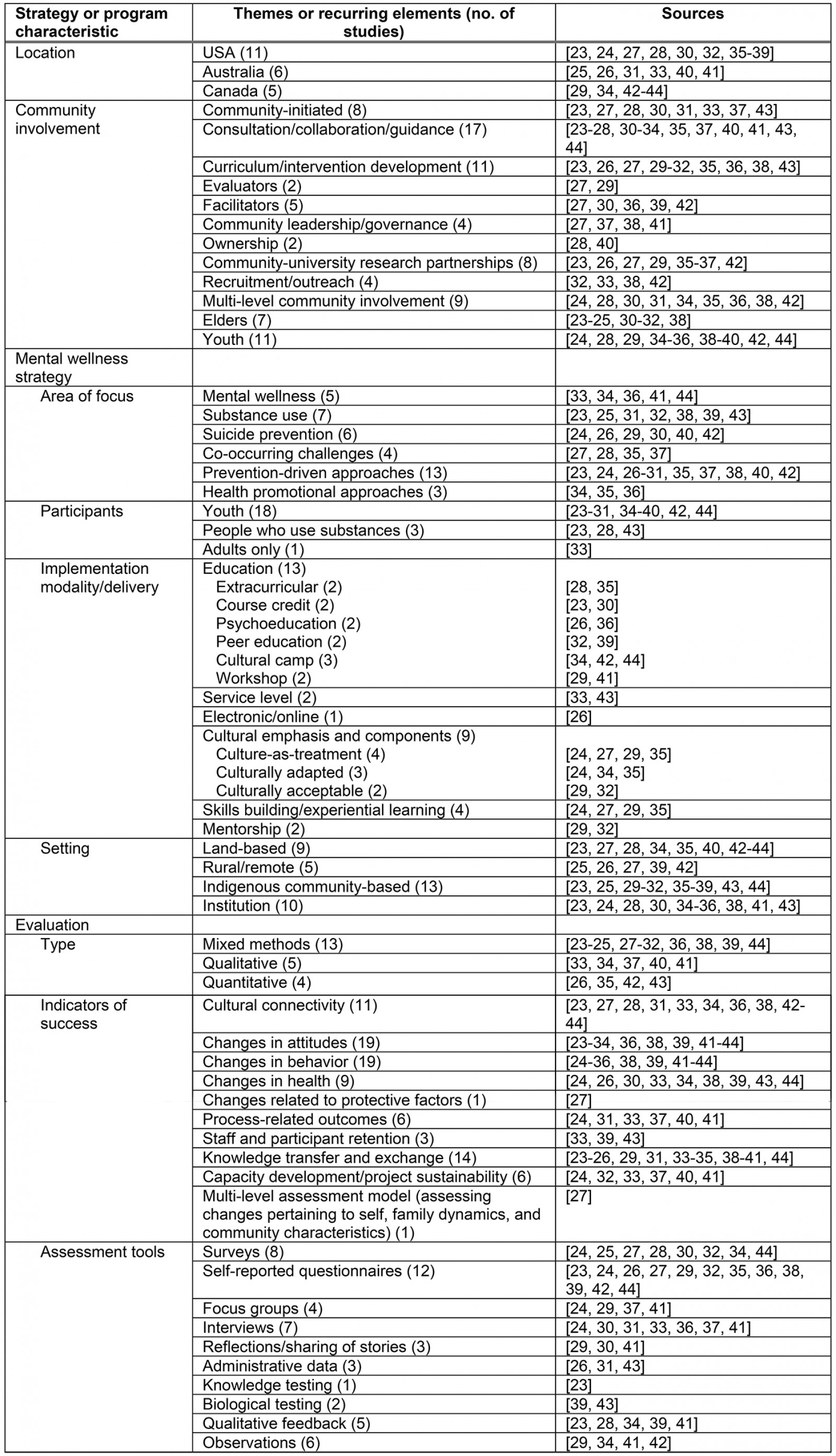

Characteristics of mental wellness initiatives: The majority of included articles were based in the US (11/22), with six based in Australia and five from Canada. Initiatives varied in focus, ranging from general mental wellness (5/22) and substance use (7/22) to suicide prevention (6/22) and co-occurring challenges (4/22). Among studies that addressed substance use in communities, a few studies designed strategies to specifically address use of opioids (1/22), tobacco (1/22), and alcohol (2/22), while others addressed overall substance use (4/22). Among studies that addressed co-occurring challenges, three studies implemented initiatives to address substance use and suicide, and one study implemented an initiative for substance use and violence. Most studies implemented initiatives that were explicitly identified by the authors as prevention-focused to address specific concerns within a community (13/22), while a few studies focused more exclusively on health promotion and awareness (3/22). Almost all initiatives were implemented for youth populations within communities (18/22), with one study addressing youth and their families. Initiatives were implemented through various modalities, ranging from an educational approach (12/22) to a systems-level or service-based approach (2/22), where the initiative was part of an existing or routine model of health service delivery for the community. Some initiatives used extracurricular or credit-based courses for school-aged youth (5/22), while others used peer education (2/22). Almost half of all included studies incorporated an element of cultural continuity in their programming (9/22). Mentorship (2/22), skills building/experiential learning (4/22), and social connectivity (4/22) formed the basis for some wellness initiatives. Some initiatives were implemented in a land-based setting within a specified community (9/22), while others were implemented at an institution situated within the community (10/22). Some initiatives were explicitly identified by the study authors as having been implemented within rural and remote Indigenous communities (5/22) across the USA and Australia. Detailed information on included studies can be found in Supplementary table 2.

Supplementary table 2: Primary findings and characteristics of included studies

Table 1: Summary of thematic coding based on the primary findings from included studies23-44

Types of evaluation, indicators of success and assessment tools: Most studies evaluated initiatives using a mixed methods approach, with qualitative and quantitative indicators (13/22). Five studies utilized an exclusively qualitative approach, and four studies utilized an exclusively quantitative approach. Some studies reported process-related indicators (6/22), while the remaining studies reported on outcomes-related measures and indicators. Outcome measures and indicators varied by the type and extent of the evaluation approach, and ranged from measures of effectiveness to community capacity building. Eleven studies measured changes in cultural connectivity through observations and the use of adapted and/or validated scales such as the Native American Enculturation Scale. Almost all studies measured attitudinal (19/22) and behavioral (19/22) changes, both pre- and post-strategy implementation, which encompassed scores on constructs such as hope, optimism, resilience, and communal mastery (joining together with kinship and social networks).

Changes in health-related measures were assessed in nine studies, which included self-reported measures of wellbeing, substance use, and suicidality. One study measured changes related to protective factors, such as perceived availability of supportive services and opportunities within the community, as well as positive peer influences. Most studies assessed changes in knowledge, knowledge retention, and overall knowledge exchange and translation processes (12/22). One study utilized a multi-level assessment model to evaluate post-interventional effects; the model encompassed indicators pertaining to individual, family and community characteristics.

Five studies documented capacity development upon strategy implementation, while one study assessed the sustainability of the mental wellness initiative. Assessment tools varied substantially across and within studies, with authors frequently adopting or adapting the use of self-reported questionnaires with validated scales for the assessment of specific constructs (12/22), surveys (8/22), interviews (7/22), feedback from participants and staff about their experiences (5/22), and focus groups (4/22). Some studies used observational methods such as taking detailed notes on observed changes over the course of the project (4/22), administrative data (3/22), and reflective exercises or sharing of stories (3/22). Two studies reported the use of biological testing such as urine drug screening, and one study reported knowledge testing.

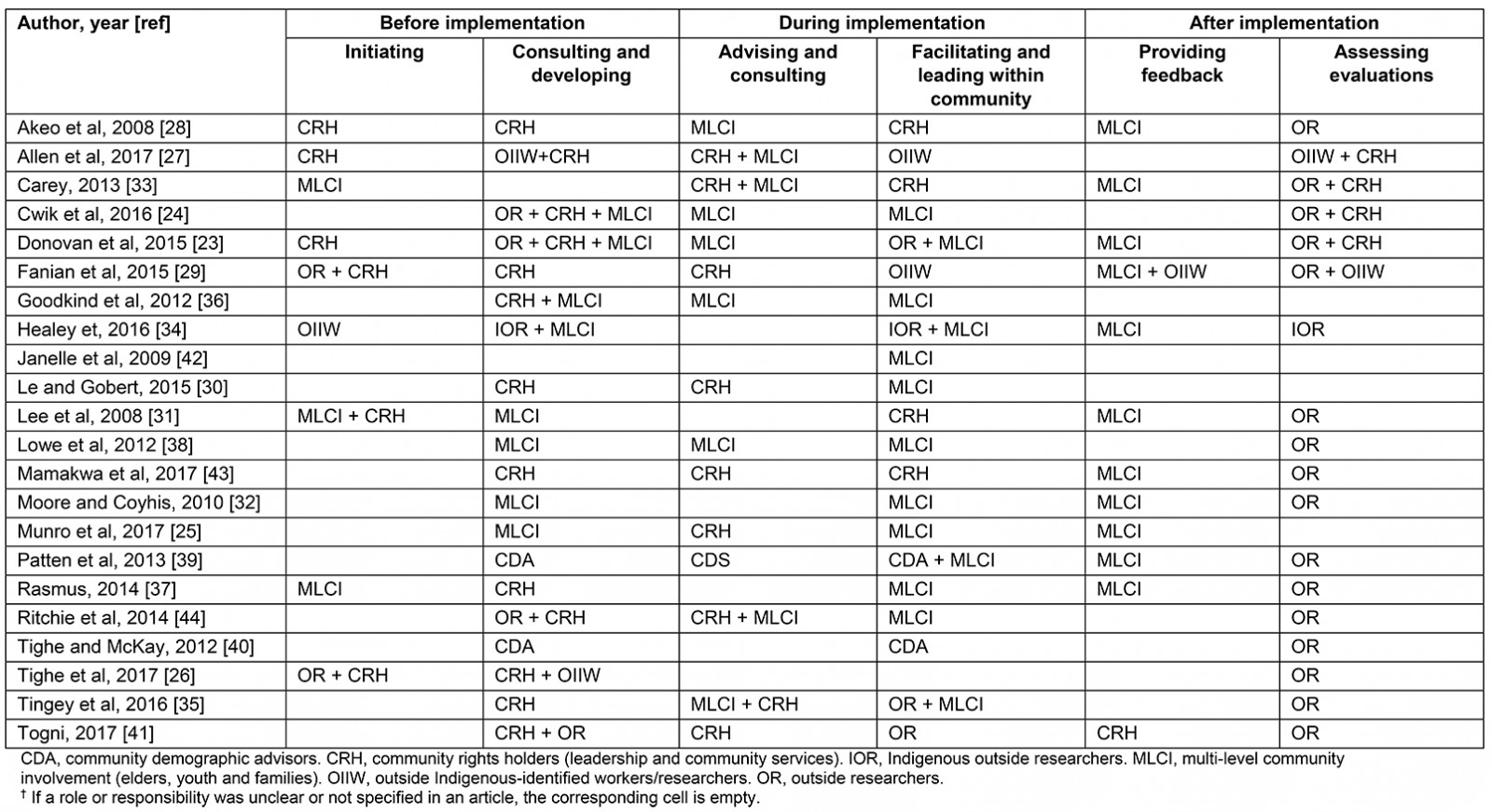

Types of community involvement in the development, implementation, and evaluation of mental wellness initiatives: Community wellness initiatives described in the articles involved some form of consultation and/or guidance from community members during the development, implementation, and/or evaluation of the initiative (17/22). Some studies conducted research through shared leadership with formal community leaders and/or research-specific advisory/governance bodies representing the community (4/22). Some studies were initiated by community members (8/22) expressing unmet needs and/or challenges with respect to mental wellness in their communities, which culminated in or stemmed from existing community–university research partnerships. Community ownership of research data was explicitly highlighted in two studies. Some studies highlighted the roles and responsibilities of communities in the development/co-development of curriculum for the initiative (11/22), and recruitment and outreach within the community for research participants (4/22), as well as acting as facilitators (5/22) and evaluators (2/22) of programs within the initiative. Most studies reported multi-level community involvement (eg youth, families, and Elders) in the development, implementation and/or evaluation of mental wellness initiatives (19/22). Some studies highlighted the involvement of youth (11/22) and community Elders (7/22) throughout the research process. Table 2 details the types of community involvement, as well as the involvement of people outside of the community, including Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers, workers, and stakeholders.

Table 2: Summary of community roles and responsibilities within included studies23†

Incorporating cultural ways of knowing and doing within mental wellness initiatives: Following a thematic analysis of included articles, four themes related to culture emerged. The first theme identified was cultural teachings and activities. Five of the articles identified ways in which the studies incorporated activities and teachings related to the respective cultures of the Indigenous peoples and communities involved in the mental wellness initiative23-27.

The second theme was appropriate use of culture. Five articles highlighted how culture can be utilized to make the mental wellness initiative more appropriate for Indigenous study participants28-32. The studies discussed how the researchers were able to build on the use of culture to connect with study participants and achieve more meaningful results by incorporating culturally acceptable practices from locally trained community members, families, and individuals.

The third theme was using land-based camp programming, which was noted in three articles24,33,34. Land-based programming refers to activities that take place on land that is removed from spaces where Indigenous peoples have been relocated as part of colonialism – land where traditions, knowledge, ceremonies, and other cultural practices, such as hunting and fishing, are practiced, taught, and revitalized45. The value of land-based learning, healing, and activities stems from a holistic understanding that all living things are interconnected, whereby human wellness is inextricably linked to creation and the relationships between all of creation46. This theme indicated that camp designs and programming were based in local Indigenous cultures. More specifically, the process of preparing for and making the journey to and from camps was an essential component of land-based programs, intending to enhance program fidelity and create successful outcomes with lasting impacts on youth participants.

The fourth and final theme was land-based knowledge sharing, included in eight articles23-25,27,28,33-35. The inclusion of land in the designs of the initiatives was instrumental for the inclusion of ‘culture as land’ as the platform for the diffusion and uptake of cultural knowledge between researchers and participants. The use of land-based activities on traditional territories and ceremonial lands was seen to increase the interest, participation, and engagement of youth in the program, resulting in a strengthened connection to the land and cultural knowledge.

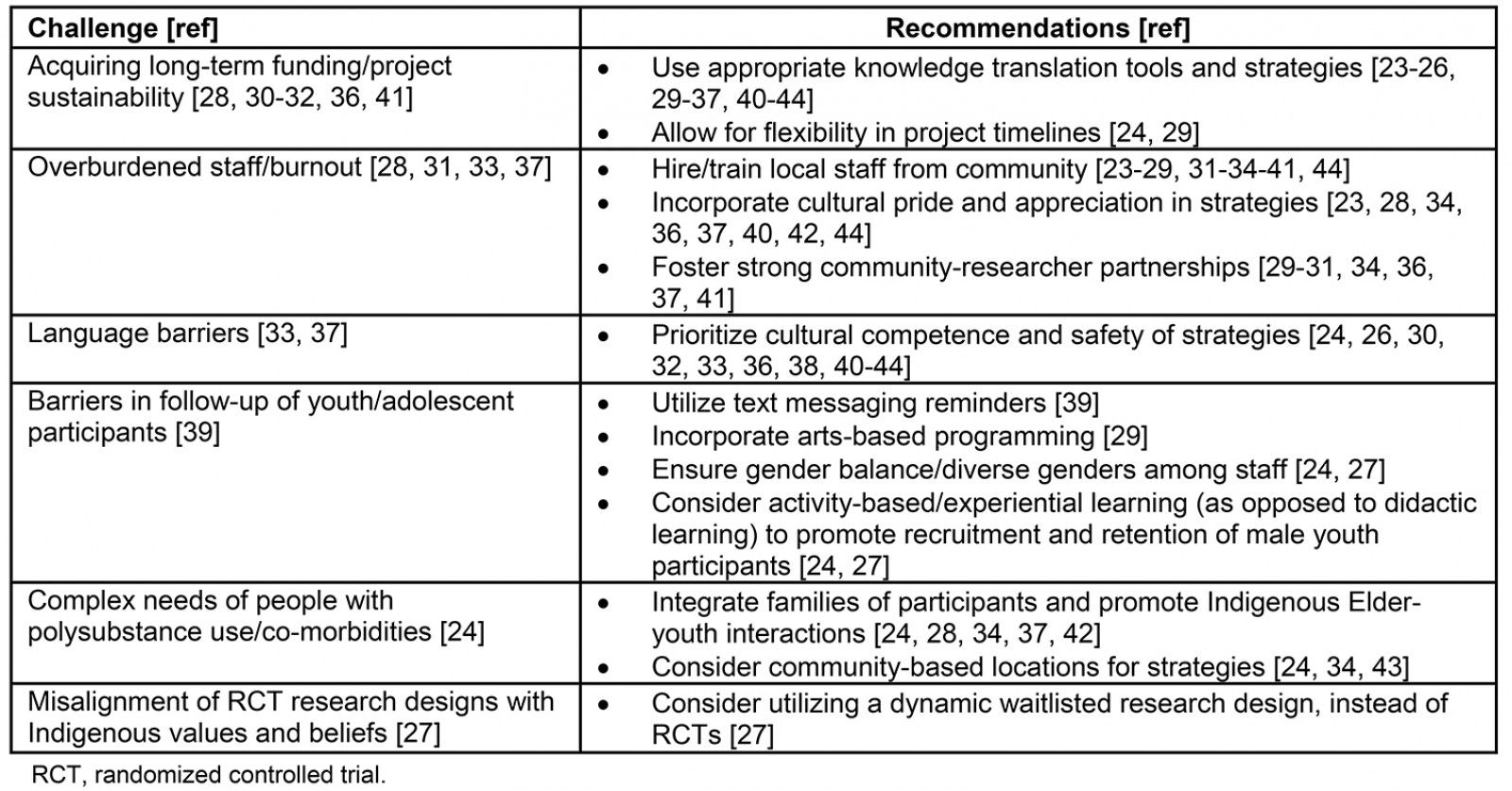

Challenges and recommendations: All of the articles included in this review reported on a mental wellness initiative that was implemented and evaluated as part of a research study. Some authors highlighted the challenges associated with implementing and sustaining mental wellness programming, pointing to problems with funding structures and lack of agency support that impeded their ability to meet research objectives within allocated time periods (6/22). A few authors expressed concerns regarding overburdened staff and community members throughout the study (4/22). Communication barriers were expressed in a few studies (3/22), with two studies highlighting the disconnect between Indigenous-speaking and English-speaking facilitators and participants. One study specifically reported challenges in following up with adolescent participants, which was overcome by the use of cellular text messaging. The complex needs of people with co-occurring substance use challenges were identified in one study as an important consideration in the design of an initiative addressing suicide prevention.

All studies included programming that was culturally relevant and adapted to address the needs of the community, with some studies highlighting the importance of cultural competence and safety (11/22). Most studies owed their success to and/or recommended hiring and training of research staff from the community (20/22); embedding appropriate knowledge translation activities that were culturally appropriate and tailored for uptake among specific demographic groups, such as youth (19/22); endorsing cultural pride and appreciation (9/22); building strong relationships with communities for a collaborative and effective partnership (7/22); integrating families or Elder–youth interactions within strategies or programs (6/22); being flexible with project timelines (2/22); ensuring initiatives were locally based (3/22); and incorporating arts-based programming (1/22).

Authors of one study highlighted the misalignment between randomized controlled trial designs and Indigenous values and beliefs, despite the effectiveness of such designs in overcoming methodological limitations of many community evaluation studies. The authors recommended the use of a dynamic waitlisted research design to incorporate an element of randomization and ensure that all research participants receive the intervention. Table 3 briefly outlines which studies experienced the aforementioned challenges and recommendations.

Table 3: Summary of challenges and recommendations identified from thematic coding of primary findings23-44

Discussion

This scoping review sought to characterize Indigenous mental wellness initiatives that have been subject to evaluation, and identify approaches used to evaluate Indigenous mental wellness initiatives. Overall, a majority of studies involved Indigenous nations and communities in Canada and the USA, and some from Australia. Initiatives were frequently tailored to address general mental wellness, with some initiatives focused on substance use, suicide prevention and co-occurring conditions or challenges. Initiatives were often designed to address youth-specific needs and challenges. The development and implementation of culture-based initiatives were emphasized in many studies, with cultural adaptation and relevance prioritized in all included studies.

Most studies evaluated the outcome(s) of a particular mental wellness initiative while very few evaluated the process of developing and implementing the mental wellness initiative. In most cases, research teams either adopted or adapted validated tools from a largely Western-informed context, or used common methods such as interviews and focus groups to elicit feedback from participants and project team members. In some studies, the roles of Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and local Indigenous leaders were important or central to the implementation of the initiative. In such cases, local and cultural perspectives were included as part of the evaluation. However, there were no reported examples of evaluation processes that explicitly used local cultural protocols and practices. In other words, most evaluation methods used in the studies were Western-informed methods and tools that included Indigenous voices and knowledge. The studies in the present scoping review did not co-develop their evaluation tools and framework with local Indigenous community members, nor were they based on traditional or local Indigenous ways of knowing and doing.

While evaluation methods or frameworks were not necessarily based on local Indigenous ways of knowing and doing, they showed that land-based programming improved mental wellness and increased cultural knowledge. The connections between land, culture, language, knowledge and healing have been well documented in the literature15,47-49. Many Indigenous peoples characterize who they are through connections to their communities, the land and all living things that surround them48. A study by Kant et al (2013)50 analyzed ‘land use’ as a determinant of participant wellbeing, finding that restrictions on land use imposed by the government had negative impacts on the health and wellbeing of individuals. It was also found that land use played a key role in the diet of individuals in terms of being able to access traditional foods, which had positive impacts on individual health and wellbeing. Kirmayer, Simpson and Cargo (2003)48, stated ‘knowledge of living on the land, community, connectedness, and historical consciousness all provide sources of resilience’ (p. S21). In short, Indigenous-led land-based activities play an important role in restoring Indigenous peoples’ health and wellness, resiliency, and self-determination of wellness practices.

As indicated earlier, only studies that involved Indigenous community members in the development, implementation, and evaluation of a mental wellness initiative were included. The majority of studies in this review actively included community–researcher partnerships with shared leadership and/or consultation with community advisory persons or groups, which consisted of individuals from different generations and of varying leadership roles within the community (such as Indigenous Elders, youth, and families). Research principles and guidelines such as Chapter 9 in the Tri-Council Policy Statement 2 in Canada22 and the Ethical Conduct in Research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and Communities in Australia51 articulate that research about Indigenous peoples must be conducted by and with Indigenous peoples52. However, only six of the studies included in this review involved community-driven research with Indigenous leadership throughout, from the very outset of the project.

Despite improvements in the ethical conduct of research through community engagement, the authors urge researchers leading Indigenous wellness research to improve clarity and transparency in the reporting of Indigenous community involvement. While most included articles reported broadly on the presence of Indigenous leadership and consultation, specific details on the individual roles, responsibilities, and duration of involvement throughout the different phases of the research project were seldomly reported. As presented in Table 2, community involvement was primarily evidenced prior to strategy implementation within the consulting and development phase,' and during strategy implementation within the ‘advising and consulting’ and ‘facilitating within community’ phases. Conversely, reporting of community involvement fell short within the initiation of strategy implementation as well as throughout the evaluation phase. To rightfully reinstate the self-determination of Indigenous peoples and their communities, any attempt towards building capacity must be corroborated with explicit disclosure of leadership and power differentials, through the description of roles and responsibilities. Further, the authors of the present article suggest that researchers self-identify their respective privileges, the nature of their relationship with the communities that they are working with, and further locate themselves within the colonial framework in published works. This step of self-identification and self-locating is critical in actioning beyond achieving cultural competency, whereby cultural nuances may be considered in the development of initiatives and adapted to fit the perceived needs of culturally diverse groups.

Conversely, cultural safety necessitates a paradigm shift towards critically acknowledging and addressing power relationships on an ongoing basis to work towards achieving health equity53. While authors in the included studies did not explicitly mention the term ‘cultural safety’ to describe the ways in which place-based cultural programming, knowledge, and practices were central to the success of their mental wellness initiatives, many of the evaluations included concepts that reflected cultural safety. Cultural safety emphasizes how social and historical contexts have resulted in health inequities and addresses power, privilege, racism, and discrimination in healthcare settings by promoting figurative and literal spaces and care that are free of judgement and discrimination. The present scoping review suggests that mental wellness initiatives that meaningfully involved Indigenous community members in all or most phases of the implementation process tended to prioritize cultural ways of knowing, doing, and being. As such, although cultural safety was not specifically identified nor established in included studies, the meaningful involvement of Indigenous community members through established partnerships and the privileging of Indigenous peoples’ culture in most included studies signals the path towards ensuring cultural safety. Future research should assess the extent of cultural safety and how it relates to defining and measuring success within mental wellness initiatives.

Limitations

Included studies were often limited by small and convenience-based sample sizes. Within a Western-informed evaluation framework, the validity of outcomes extracted from these studies must be interpreted with caution, as the authors did not use a quality appraisal tool. However, the objectives of the present review concerned a broad scope of available literature on community-based mental wellness initiatives, and the validity of the actual outcomes from the evaluations merit a separate and more nuanced investigation. As this review sought studies that involved Indigenous communities as co-leads in research efforts, community involvement was assessed and summarized as an indicator of the study’s ‘quality’ in upholding ethical standards of research by working with Indigenous communities. However, a few critical appraisal tools have recently been developed to assess Indigenous community involvement, such as the CREATE Critical Appraisal Tool54 and the Well Living House Quality Appraisal Tool55, and hold great promise for future investigations on this topic. This review approach is strengthened by its comprehensive search of both published and unpublished, grey literature sources. Additionally, a thematic analysis approach was used to succinctly and rigorously summarize key themes across all studies. The authors also note that the impetus for this scoping review came out of a mental wellness project in Canada56, where members of the Community Advisory Circle articulated the need for a review, and involved all of the co-authors from this review to some extent. As such, the grey literature search included databases and websites that focused more heavily on Indigenous projects in North America than in Australia or New Zealand. Additionally, the key search terms that informed the search strategy were guided by a North American context and so the strategy is likely to have missed specific terms pertaining to mental wellness from an Australasian context.

Conclusion

This scoping review provides examples and commonalities across diverse Indigenous community mental wellness initiatives that have been evaluated. This review offers examples and themes for the development of wise practices for community mental wellness initiatives – for Indigenous communities, governments, and researchers alike. The ethical and moral imperatives of ensuring Indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination necessarily includes access to and support for mental wellness initiatives. Furthermore, the authors argue that the initiatives’ approach to evaluation and establishing success must be guided by local Indigenous knowledge, improved or renewed connection to land, fostering community strengths, and the sharing of roles and responsibilities among those involved in this work. As more Indigenous communities and leaders govern and guide mental wellness initiatives, including research, this scoping review suggests that culture as a form of healing is an important direction to consider when addressing the specific health priorities and preserving the cultural identities and strengths of Indigenous peoples.

Acknowledgements

This paper was completed as part of a study entitled "A Regional Knowledge Mobilization Model for First Nations Mental Wellness Strategies: Building on Local Knowledge and Networks for Provincial and National Impact", funded by the Ministry of Health and Long-term Care's Health Services Research Funding Operating Grant (FRN-2017-01097). The views expressed in this paper are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Province (the funder).