full article:

Introduction

Podcasting as a medium emerged in 20041. These pre-recorded audio resources have grown dramatically over the past two decades2,3 and there was a significant increase in their popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic4. Podcasts are very accessible in most jurisdictions, making information available to a wide audience at low or no cost. They often facilitate discussions from medical professionals and have been used to increase health literacy and deliver educational resources to a range of clinical and non-clinical populations5-8. An analysis of podcast usage demonstrated that listeners are motivated by gaining information and entertainment, and value podcasts for their convenience and diversity of content9. Another study examined college students’ podcast preferences and identified entertainment, escapism and gaining information as key motivators10.

The pandemic saw increases in reported mental health distress11 as well as diminished access to treatment services11,12. Referrals to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services in Ireland have risen and researchers project a further increase, with the need for additional service funding to cope with the strain13,14. Additionally, access to mental health services is a particular issue for those in rural areas and for Indigenous groups15-18. Thirty six percent of Ireland’s population live in rural areas, which is approximately 10% higher than the EU average. A new Eurobarometer report on mental health has revealed that 9 in 10 EU respondents (89%) consider that mental health promotion is as important as physical health promotion; the report also noted that people in Ireland experience the highest level of difficulty in accessing mental health services among citizens of the 27 EU member states19. In addition, 0.28% of respondents in the study were members of the Indigenous Traveller community (0.7% of the general population are Travellers).

The Irish Traveller community are an Indigenous, distinct ethnic minority group, with a long tradition of nomadism and a strong cultural heritage including their own language and traditions. Data on the inequities in mortality, health and access to health services experienced by the Traveller community in Ireland demonstrate higher rates of death by suicide and other sudden causes among members of this marginalised minority group than in the general population20. It is estimated that the suicide rate among Travellers is more than six times higher than in the settled community (general population)21 and Travellers’ struggle to utilise mainstream mental services due to structural racism and negative experiences of services22. Researchers argue that mental health promotion initiatives for the community should focus on a range of psychosocial interventions, including enhancing wellbeing and self-esteem, reducing mental health stigma, and the promotion of Traveller culture and positive self-identity23. Given the systematic barriers to existing services, novel approaches to mental health promotion could be utilised; podcasts for the community, produced by the community, could be one such tool.

Mental health literacy (MHL) is ‘knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid their recognition, management, or prevention’ (p. 184)24. The term MHL has several definitions, and it is argued within the literature that many definitions are too narrow, with a tendency to focus on mental ill health rather than a broader view of wellbeing. Additionally the continued expansion of the term and a lack of consensus can lead to confusion25. Many authors have argued that MHL based on psychiatric diagnostic frameworks can increase social withdrawal and stigma26,27. While there is much critical review of both the conceptualisation and measurement of MHL, research exists that indicates improvements in MHL reduce stigma around mental illness28, increase help-seeking behaviours29-31 and promote early intervention24. Lower levels of MHL are associated with maladaptive coping strategies such as drug and alcohol use24,32,33. Improving MHL can be achieved through psychoeducational interventions that may include mental health-related podcasts. Researchers have demonstrated that podcasts facilitate meaningful connections with hosts and listeners34. A critical review of the literature would indicate that MHL material should extend beyond dichotomous views of mental ill health and mental wellbeing and should be anchored in sociocultural perspectives with a goal of empowerment for the end user35.

Mental health-related podcasts are widespread and a wide variety are available to the public36. Recent research demonstrated that those who listened to mental health-themed podcasts held fewer stigmatising attitudes to those experiencing issues with their mental health37. That said, research in this area is scarce and little is known about listener experiences. Quantitative results from the present study shed light on the population’s motivations, listening habits and outcomes. Participants with the lowest levels of education and mental health literacy reported the most significant benefits from listening to mental health-related podcasts38. The present study is the first of its kind as it qualitatively explores the experiences of mental health-related podcast listeners.

Methods

Participants

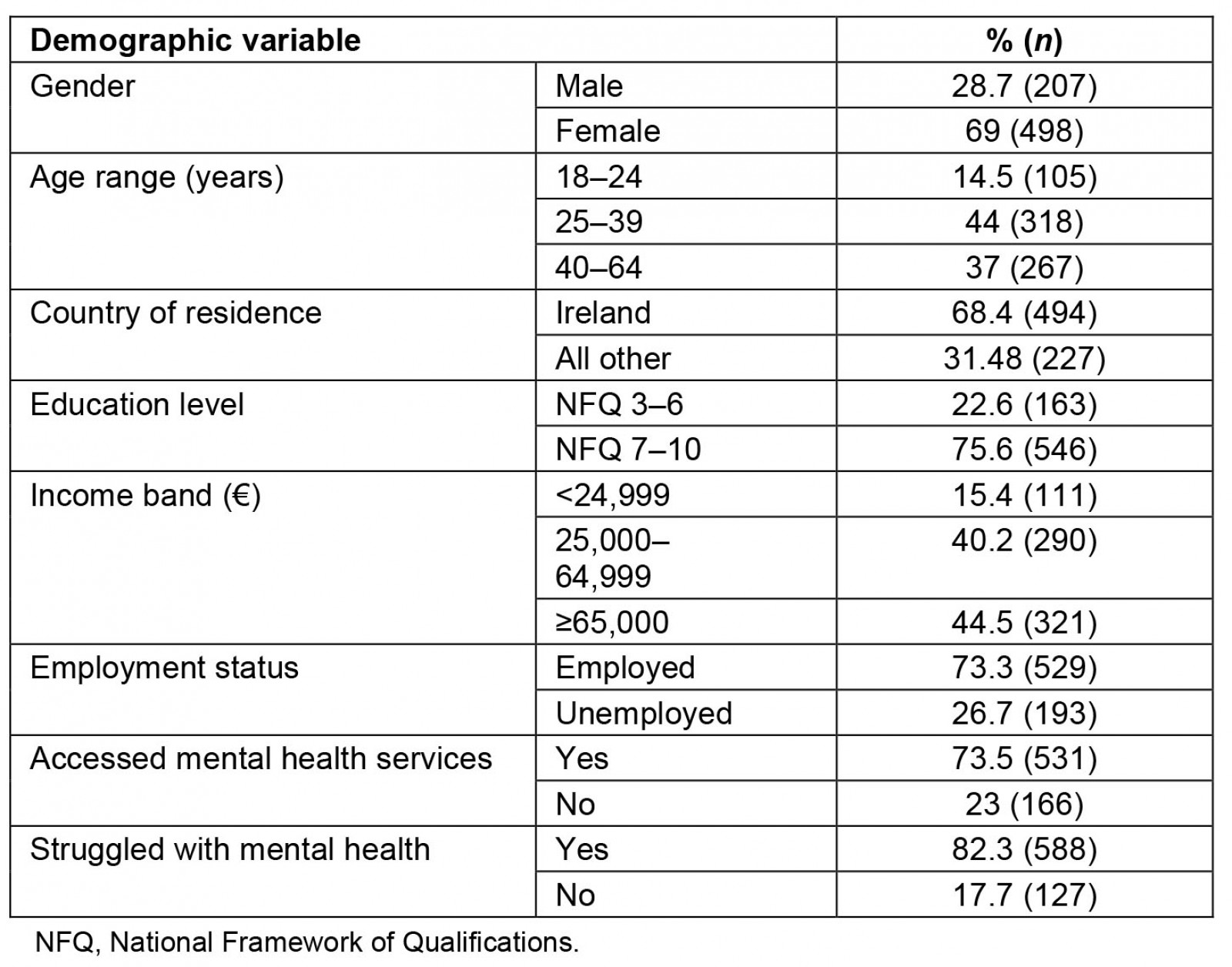

Participants (n=722) were recruited through an online survey via Qualtrics. Participants aged ≥18 years who listened to mental health-related podcasts were included in the study. A mental health-related podcast was defined as any podcast ‘which deals with topics around mental health/psychology’. The sample comprised 28.7% males (n=207), 69% females (n=498), and 1.9% non-binary (n=14), while 0.4% chose not to disclose their gender (n=3). The majority of participants fell within the age range of 25–39 years (n=318, 44%). The sample included in the qualitative analysis at hand is made up of 522 participants as 120 individuals did not provide answers to the open-ended questions.

Table 1: Demographic overview of the sample

Procedure

A survey was designed using Qualtrics, which consisted of closed and open-ended questions. The survey link was shared on various social media platforms and via email contacts. Data were exported to Microsoft Excel and collated, cleaned and coded. Level of education and household income were grouped into categories according to the Irish National Framework for Qualifications and the Irish Central Statistics Office respectively; and mental health diagnoses were grouped into categories according to the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders diagnostic categories39. Incomplete responses, defined as responses that did not proceed beyond the demographic questions, were removed. Participants were presented with a series of statements and ranked these statements on a scale of 1–10 in terms of the relevance for their motivation when listening to mental health-related podcasts. Participants were requested to provide further detail in a comment box relating to their response on each statement. The statements were ‘learn new information and skills’, ‘normalise problems and foster connection’, ‘reframe challenges and give me hope’, ‘process painful feelings and experiences at a safe distance’, ‘help acknowledge negative emotions within myself’, ‘increase understanding about myself and my circumstances’, ‘develop new ways of dealing with problems’ and ‘consider making changes to my behaviour or circumstances’.

Qualitative data was exported to a Microsoft Word document, and thematic analysis, as outlined by Braun and Clarke40,41, was carried out.

Research design and analysis

Both closed and open-ended data were gathered using an online survey. Demographic items included age, gender, ethnicity, household income, educational level and employment status. Participants were asked about listening frequency and reasons for listening. Participants were asked about their mental health history. Three open-ended questions asked participants what they ‘take away from’, ‘learn about themselves (or a loved one)’ and ‘find most useful about’ listening to mental health-related podcasts.

Participants in this study were a very engaged group, and the researchers noted that a significantly higher volume of qualitative responses were submitted than anticipated. These responses were very detailed: 51 pages of data were extracted from the Qualtrics survey into a Word document. The first and second author independently reviewed three pages of data, generating initial codes. Divergences were discussed until unanimity was achieved. The first author coded the remainder of the data and generated themes. Following this the second author reviewed the initial themes. Some themes merged and discussion between the researchers continued over several weeks until consensus was reached. The themes were named and finalised. A reflexive positionality was established, and each researcher maintained an awareness of their own subjective influence on the research process throughout. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist42 served as a systematic tool to guide the research process, informing the data analysis process. Given that the data were from surveys and not interviews, a semantic approach was utilised; the authors did not go beyond the words of the participants. According to Byrne, ‘semantic codes can be described as a descriptive analysis of the data, aimed solely at presenting the content of the data as communicated by the respondent’ (p. 1397)43.

The first author generated initial codes, and both authors then engaged in continuous dialogue about theme generation until agreement was reached. Given the subjective nature of data interpretation, the first author engaged in journalling about their experience of the analytic process. This further facilitated conversations between both authors. The number of themes initially generated decreased as themes were merged or removed.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted for this study by the School of Applied Psychology ethics committee, University College Cork (ref EA-MMH12132021725). Participation was anonymous and voluntary. Informed consent was received from all participants. Contact details for the researchers and a range of support services were provided in the information and debriefing statements. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees.

Results

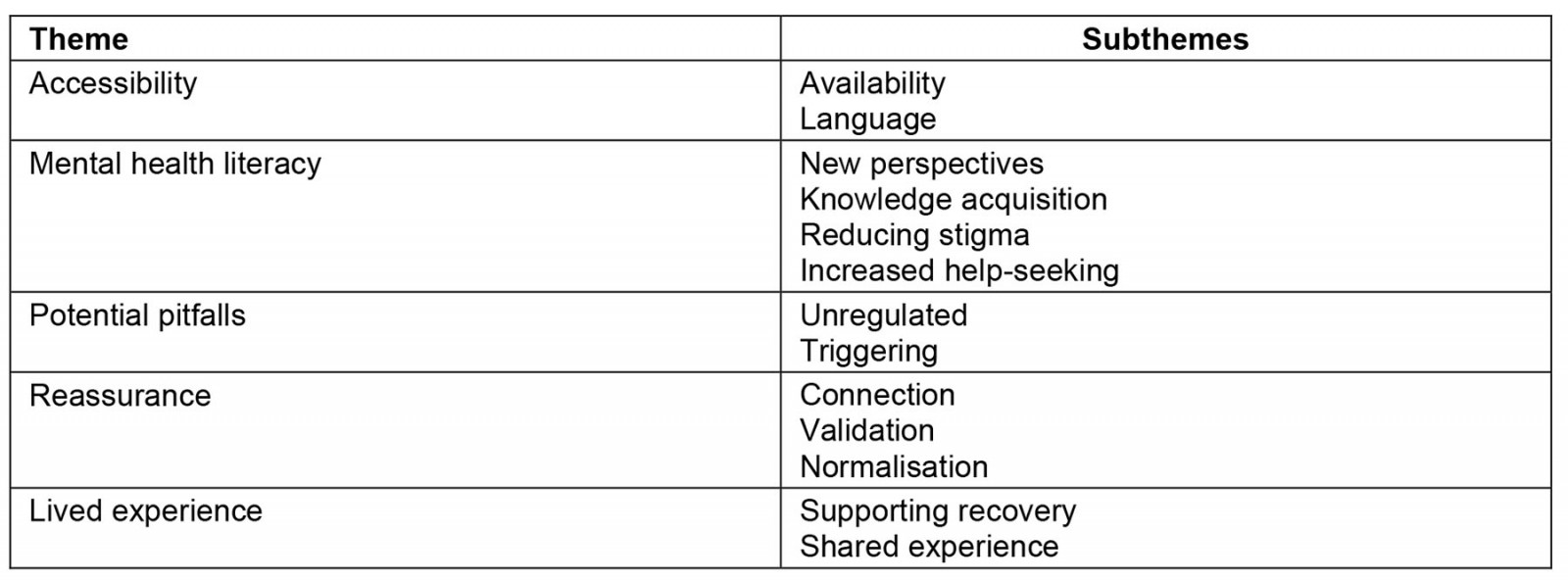

The inductive thematic analysis40,41 on data from three open-ended questions generated five themes: mental health literacy, potential pitfalls, reassurance, lived experiences and accessibility. These themes and subthemes (Table 2) offer further insight into the experiences of mental health-related podcast listeners.

Table 2: Study themes and subthemes

Theme 1: Accessibility

This theme was constructed from participants’ responses that pertained to several factors that make podcasts accessible. At the forefront of these factors is the fact that most podcasts are readily available, free or inexpensive: ‘The podcasts are an ongoing support and free. Even when we do pay to support creators, Patreon donations are minuscule compared with GP and counselling costs’ (participant 120). In this example, the contrast between the cost of accessing mental health services and that of listening to mental health-related podcasts is highlighted, in addition to the ongoing accessibility of information beyond a consultation period: ‘They can take 21 minutes to explain something while a GP will rush you out the door because they’re busy. If you didn’t catch all of it you can replay it and take notes’ (participant 721). For this participant, consuming the materials presented in podcasts is more accessible as they can do so at their own pace and in a controlled manner, where they can revisit the material if necessary. Echoing this sentiment, another participant wrote that ‘I can decide when, where, and how much to take in. I can revisit the episode’ (participant 146). Furthermore, this theme captures a sentiment among participants that while formal services exist, they are difficult to access: ‘There is nowhere else to gain this understanding, services are advertised well but very hard to find when you go looking’ (participant 246). The following quote highlights the immediate access to information provided by this medium: ‘There’s no waiting list, just press play’ (participant 84).

Finally, core to the theme at hand, accessibility of the language, participants expressed that the ‘non-scientific’ approach to the delivery of psychological material was ‘useful’, ‘I find [name of podcast] is especially accessible in explaining complex

psychological and sociological theories’ (participant 152). This is crucial when considered in the context of psychoeducational material, which often seeks to communicate complex concepts to service users; for example, ‘Cuts out academic jargon and makes complex theory accessible’ (participant 722).

The present theme provides us with a unique insight into the accessibility of mental health-related podcasts. People can listen at times that suit them, listening back if required, and the language used is jargon free and understandable. Participants contrast this accessibility with barriers they perceive with formal mental health services. This may be particularly relevant for people who live in rural and remote locations where there is an absence of any service provision. In addition, there are some learnings here for the delivery of formal services where they do exist: participants require more time in consultations and language that is accessible.

Theme 2: Mental health literacy

This theme was constructed from the data related to MHL. Many participants report that their MHL improved, as they gained new perspectives and furthered their language and facilitated knowledge acquisition of mental health topics: ‘Informed on real meaning of OCD [obsessive compulsive disorder]; so much more than just ‘hand washing or checking doors and switches’ compulsively’ (participant 699). Participants outlined what facilitates this psychoeducation, noting that gaining access to professionals is an important factor: ‘Education from expert/trained psychology professionals as guests on show’ (participant 599). This aspect related to not only personal development but also professional development: ‘As a psychology graduate, I also appreciate the opportunity that these podcasts provide to listen to experts in psychology that I may not otherwise have access to …’ (participant 391). It is evident that a range of professions (eg therapists, teachers, healthcare professionals) are using podcasts as a means for continuing professional development and gaining new perspectives: ‘Some help me see the world through other people’s eyes and struggles, and others help me learn how to better help and support my clients and my loved ones’ (participant 681). This teacher reported that podcasts, ‘really help me in my profession. I am a principal of a junior DEIS [Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools program] school and I work with children and families who have experienced trauma. They also help me when working with staff’ (participant 187).

Participants were also asked, ‘What do you learn about yourself (or a loved one) from listening to mental health-related podcasts?’ Responses to this question indicate that podcasts facilitate a growth in MHL with regard to the participant’s own mental health: ‘How my misuse of alcohol has been an escape from my issues, also how I can incorporate coping strategies in my everyday life’ (participant 72). The data also suggest that, core to their development in MHL, participants became equipped with language to understand their own mental health in a more self-reflective manner: ‘Promote reflecting on my own experiences. Sometimes they provide the language to describe the feelings I previously could not properly articulate’ (participant 428).

Consistent with this, participants from this sample appear to be developing an increased awareness of services. The data from the current study indicate that, rather than deter people from seeking professional support, podcasts instead reduce stigma – ‘I’m less hard on myself. They have encouraged me to open up and speak about my issues’ (participant 649) – and increase attitudes favourable to help-seeking behaviour, consistent with research in the area of MHL22: ‘It can de-stigmatise mental health issues as these discussions are happening between people that have no specific authority over you – you choose to engage with their content if and when you are in an appropriate mental and emotional state, instead of being bombarded with promoted ad campaigns’ (participant 54).

Furthermore, through listening to the content provided in mental health-related podcasts, participants are improving their MHL, developing new perspectives and in turn developing a deeper sense of self-compassion: ‘I’ve developed a deeper sense of compassion and learned to be kinder to myself. I also have more awareness of the impact internalised shame has had on me and those I love …’ (participant 216).

Participants also reported developing different and new perspectives with increased compassion for other people: ‘… others have the same reactions and difficulties as myself, but also not to judge the behavior of others. There may be reasons I don’t know or yet understand’ (participant 669).

A contrast between formal services and podcasts appears with respect to MHL knowledge acquisition. There was very much a view that podcasts provided a clearer understanding of mental health issues: ‘Has been helpful in educating me on my daughter’s mental health issues, more than the health care professionals who she’s under’ (participant 663).

The following quote highlights an idea that consistently appears throughout the data: the contrast between formal services and mental health-related podcasts: ‘I’ve learned coping skills and some tools to help when things get really difficult. My doctors never gave me those. Medication has not given me those’ (participant 649). This participant also wrote that they feel ‘let down by the system’ but that they have gained ‘compassion’ and ‘support’ through listening to mental health-related podcasts. This is a powerful sentiment and perhaps highlights a gap in expectations versus delivery. Mental health services primarily respond to acute distress, and MHL is a stage 1 intervention more appropriate within community-based settings. The attention to the importance of empathy and compassion was an underlying aspect throughout the data: ‘I hope more people will listen to those who have experienced such hardships and show empathy instead of blame. I grew up in an area where many of my peers went to prison because no-one tried to understand them or showed them any respect’ (participant 202).

To conclude this theme, it is apparent that the primary benefit from listening to mental health-related podcasts is the development of increased MHL. This knowledge acquisition relates to a greater understanding of mental health in general, as well as a deepening of knowledge regarding oneself and others. When considered in the context of the relevant literature, this powerful takeaway may be a catalyst for personal development in addition to reduced societal stigma around mental health.

Theme 3: Potential pitfalls

Some participants were concerned with podcasts being unregulated and frequently facilitated by individuals with no professional mental health training: ‘I do think with a lack of access to professional services and increased availability of podcasts there is a risk that people can take a podcast host’s advice as seriously as they would a healthcare professional’ (participant 391).

However, the data didn’t indicate that this was occurring; in fact, the data indicated the opposite was true and podcasts were changing attitudes to help-seeking behaviour (eg ‘I’m less hard on myself. They have encouraged me to open up and speak about my issues’; participant 649). It does however raise a question about regulation in this space and the potential for bad actors to provide pseudoscientific or erroneous advice. Given that our data indicate that podcasts are being utilised by mental health professionals, it may be advisable that mental health-related podcasts be endorsed by professional bodies. This will allow the public to feel assured that the content is considered safe and appropriate.

Some wrote that listening to mental health-related podcasts was a triggering experience or left a residual negative feeling with them: ‘I found some triggered me as I am terrified about being diagnosed with serious mental health conditions but really loved listening to podcasts about people in recovery and how they overcame all obstacles’ (participant 92).

Despite the relative scarcity of such comments within the data, it is crucial to recognise that, for these individuals, mental health-related podcasts may be a triggering experience; creators should consider specific content warnings for each episode.

Theme 4: Reassurance

Under this theme, participants indicated that mental health-related podcasts have helped them to develop a sense of connection to others, through learning that ‘suffering’ with mental health issues is ‘normal’. Many individuals noted the value of connection – mental health-related podcasts helped them to feel ‘less alone’ in their struggles: ‘I’m not alone, others feel the same it’s validation, gain understanding and empathy towards others people’s struggles’ (participant 142). Participants spoke candidly in response to the question ‘What do you take away from listening to mental health-related podcasts?’: ‘I learn that other people have a wide variety of problems too, and that I’m not the only one who feels that they’re facing what sometimes feels like insurmountable and immovable obstacles’ (participant 553).

Core to the above quotes is a sense of reassurance gained by listeners. Several participants used the word ‘validation’ to capture this idea: ‘Understanding, validation, support that I am not alone in this struggle (which builds self-esteem when I am feeling very dysfunctional)’ (participant 646).

Congruent with the aforementioned theme of MHL, many participants wrote that through this connection, they have gained a sense of self-compassion – ‘When I hear about the issues others bring up, it helps me feel less alone and more self-compassionate’ (participant 625) – and have tackled feelings of shame and loneliness: ‘It’s helpful to hear about others who have had similar experiences, to know that you’re not alone, because when you’re in the depths of a bout of depression it’s a very lonely place to be’ (participant 370).

It is clear from the data that many participants gain a sense of connection and validation from listening to mental health-related podcasts.

Theme 5: Lived experiences

Many participants highlighted the importance of hearing lived experiences of podcast guests who have struggled with their mental health. This theme emerged from a large number of quotes, which underscored the benefits of hearing the journeys of others. Core to this theme is a sense that participants find the ‘authenticity’ of shared peer experience useful, especially when they are similar to their own: ‘While I’ve suffered from depression for 10 years now I sometimes still struggle to describe it to family and friends, listening to peers share their journey helps give me both the language and the confidence to speak more about my lived experience’ (participant 370).

In many instances, participants get ‘hope’, ‘It gives me hope when I hear what other people have gone through and how they turned their life around’ (participant 74). Their responses reflect changes in beliefs around help-seeking: ‘Listening to others stories and struggles help me identify my own struggles and understanding the benefits of reaching out and getting support for my personal issues’ (participant 169).

However, whether this reflects an impact on behavioural change is not clear and warrants further investigation. For individuals suffering with mental health issues, this hope and connection may contribute to their recovery journey: many of them are handling some very difficult situations extremely well: ‘I hear that and think 'If they can begin to recover and attain some measure of peace, then surely I can'’ (participant 678).

This theme is of particular importance as it facilitates a parasocial relationship between the listener and the podcast speaker, which appears to contribute to the enjoyment of the listener and their personal development.

Discussion

Thematic analysis was conducted to examine the data elicited in response to three open-ended questions (‘What do you take away from listening to psychology/mental health-related podcasts?’, ‘What do you learn about yourself (or a loved one) as a result of listening to psychology/mental health-related podcasts?’ and ‘What do you find most useful about listening to psychology/mental health-related podcasts?’). Five themes were constructed from the data, which provided an insight into the experiences of listening to mental health-related podcasts. The results will be contextualised and discussed considering the extant literature on this topic.

While the existing literature points to issues with the definitions and measurement of MHL, podcasts have the potential to enhance people’s understanding of mental wellbeing. This interpretation is supported by the rich and detailed data presented under the theme of MHL. Participants made it clear that gaining new language and perspectives to understand mental health issues has been a major takeaway. In addition, it is evident that hearing the lived experiences of others is an important factor in facilitating psychoeducation. The existing literature on this matter is extensive and at its core is the view that formal mental health services have neglected to incorporate contact and lived experiences into care planning44. Results from the thematic analysis indicate that this ‘promising strategy’ of building contact with mental health issues45 is afforded to listeners, providing them with diverse perspectives and tackling stigma46. Byrne and Wykes47 indicate that those with lived experiences can provide ‘common-sense’ and first-hand understanding, which can equip individuals with knowledge to survive and thrive with mental health challenges. The present results echo this belief.

This positive experience is further bolstered by evidence provided under the thematic heading of lived experiences, where participants indicated that feelings of ‘hope’, ‘calm’, and ‘gratitude’ were central to their listening experience. Hope has been recognised in the literature as crucial to the mental health and addiction recovery processes48,49. Moreover, these podcasts have increased thinking about help-seeking behaviours and understanding of self, as participants stated that podcasts have helped them to learn coping strategies, directed them to other services and resources and deepened their sense of self-compassion. However, a limitation exists in the data: it is not clear whether this change in thinking about self has resulted in actual increased help-seeking.

Core to much of the literature concerned with the benefits of podcasts as a medium is their accessibility. Researchers have indicated that their free (or low-cost), easily accessible nature, combined with their facilitation of professional discussion makes podcasts a valuable educational resource10,50-52. The results at hand provide in-depth support for this notion. Specifically, within the theme of accessibility, participants value podcasts for their cost-effectiveness and ease of access, particularly when compared to formal services where waitlists and ‘being rushed’ are central to their experience. Thus, accessibility is key to the success of the medium. This fact is of relevance when held in light of chronic barriers to accessing mental health services such as wait times53, and the fallout of COVID-1913, and underserved groups such as Indigenous populations. A limitation of the study at hand is that it didn’t sufficiently determine the urban–rural divide.

Finally, research indicates that social disconnection is a significant contributing factor and outcome for poor mental health, particularly in the context of COVID-1912. Qualitative results indicate that a stronger sense of ‘connection to others’, ‘validation’ and ‘normalisation’ of mental health issues has been core to participants’ experiences. This offers evidence for the success of the medium. Moreover, the effect that this increase in connection and normalisation has on an individual’s personal mental health cannot be understated. Overall, the results indicate that podcasts are valued by the public as an effective medium for enhancing mental health literacy, decreasing stigma, and increasing hope and connection.

Strengths and limitations

A large number (n=722) of participants provided valuable insights on what they gain as podcast listeners. Fewer than 10 participants reported negative feelings about mental health- related podcasts. However, the open-ended questions followed a series of eight statements53, which participants ranked for relevance on a scale of 1–10 (e.g. ‘Podcasts allow me to: Learn new information about myself; Normalise problems and foster connections; Reframe challenges and give me hope; Consider making changes to my behaviour or circumstances’). It is likely these statements influenced the content of the open-ended responses.

While attempts were made to recruit international participants, a limitation of the study is that 68% of the respondents are an Irish sample. Characteristic differences across those who responded and those who did not were not analysed. Similarly, the types and quality of podcasts listened to was not part of the analysis. This could form part of a further study. Replication of the study in a broader demographic would provide more valuable insights into the role of podcasts across urban, rural and more culturally diverse samples. While Ireland’s rural population is larger than the EU average, with well-documented service access issues for the rural dweller, this study did not collect data on the urban–rural divide. Future studies should assess whether differences in use of mental health-related podcasts exist between these two groups, and whether rural populations consider such podcasts as a helpful additional tool in the absence of local services. The study reports some findings from the Irish Traveller community; this Indigenous community is underserved within mainstream services. A limitation of the current study is the small number recruited from the community; a future study should seek to work specifically with the community on the potential role of podcasts as a novel tool for addressing MHL within the community. This work should be made by the community for the community to ensure that material is culturally appropriate.

Implications

The current study identified the positive role that mental health-related podcasts play in the development of MHL, reducing stigma and increasing help-seeking behaviours. Participants also noted the accessibility of podcast material, both in terms of ease of access to the information and the accessible language used. Participants were critical of formal service providers and there are lessons to be learnt from the views reported here. The quotes reflect changes in beliefs around help-seeking; however, whether this is reflected in behavioural change is not clear and warrants future investigation. Podcasts that are ethical and informative have the potential to reach people in underserved communities and should be considered as a form of psychoeducation.

Funding

No funding was provided for this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.