full article:

Introduction

Many remote-living Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities reside in extreme disadvantage with household incomes lower than the Australian median and poor environmental conditions, including overcrowded houses and poor hygiene1, which are established risk factors for ear disease in children. Such conditions promote high rates of bacterial carriage with increased likelihood of cross-infection, usually between siblings2. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (hereafter Indigenous) have one of the highest rates of otitis media (OM) in the world3.

Remote Cape York, in north-eastern Australia, has a high Indigenous population1 and similarly reports high rates of OM4. From this region, school hearing screening reported during 2012–13 indicated that 7 percent of children had identified ear perforations (one or both ears) and 12 percent had hearing loss over 35 decibels in one or both ears4. Despite these high rates of OM and associated hearing loss, there remains poor access to ear, nose and throat (ENT) services across the region. The state health organisation provides services in two out of 10 regional communities, offering biannual ENT specialist team outreach visits to Indigenous children aged under 18 years. However, for all remaining remote communities in the region, patients have to attend a hospital outpatient appointment at the nearest referral hospital (up to 800 km away) to access specialist ENT care, which requires extensive travel for each patient.

In December 2016, the Queensland Government put forward a recommendation to the Australian Government for a coordinated national approach to the challenge of OM and associated hearing loss among Indigenous children. Outcomes sought by such an approach would include early identification and management, within primary health, leading to reduction in chronic forms of the disease, and therefore lower costs associated with tertiary service provision5; consistency in referral pathways and clarity around the roles and responsibilities of health practitioners; improved collaboration and coordination, and therefore better information sharing and reduced duplication between health services; and better data collection to aid efficiencies to service planning3. However, to date, few policy actions have occurred in response to these recommendations.

This rapid literature review was conducted to investigate characteristics of successful outreach service models to inform the development of a revised service model for ENT services for this remote region, taking into account the above principles3,5. It is anticipated that the new service model will deliver increased primary health care while reducing hospital outpatient waitlists.

Research question

To inform the development of culturally appropriate and sustainable ear health and hearing outreach service, we sought an answer to the research question: ‘What are the characteristics of successful outreach services which can be applied to remote living Indigenous children?’

Methods

‘Rapid reviews streamline traditional systematic review methods in order to synthesize evidence within a shortened timeframe’6. They are often performed to inform decision-making or commissioned by health policy-makers7. This rapid review was written for the Queensland Government and prepared in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines8. A search strategy was developed in consultation with an accredited librarian.

Search

A comprehensive search of three major electronic databases (PubMed, CINAHL and MEDLINE) and two websites (Australian Indigenous HealthInfo Net and Google Scholar) was conducted for peer-reviewed and grey literature, utilising Queensland Health Clinician Knowledge Network’s EBSCO host as the interface. Searches were conducted between 9 December 2016 and 15 December 2016. Additional searches of Google Scholar were conducted in late January 2017. Database searching was supplemented by reviewing references from identified key articles for further relevant studies. Additional references were identified from the HealthInfo Net9 and Google Scholar for ENT service delivery models.

The search was restricted to human studies published since 1997 in the English language. Each database was searched separately using the following keywords or combinations thereof:

- MH = MeSH headings/subject headings. KW = general keyword term. Databases searched: CINAHL, Medline, PubMed.

- KW Aborigin* OR KW indigenous OR KW Torres Strait OR MH Oceanic Ancestry Group

- MH Audiology OR MH Hearing OR MH Hearing Disorders OR MH Otolaryngology OR MH Otitis Media

- MH Outpatient services, hospital OR MH health services, indigenous

- MH Rural hospitals OR MH Rural health services

- MH otitis OR KW otitis OR MH hearing loss, partial OR KW deafness OR KW hearing loss

- MH multidisciplinary OR KW multidisciplinary OR MH telemedicine OR KW telehealth

- MH health care delivery OR KW health care delivery

- MH rural area OR KW rural area OR MH regional area OR KW regional area

- MH child health service OR KW child health service

- MH outreach OR KW outreach OR MH specialist service OR KW specialist service

Data collection and analysis

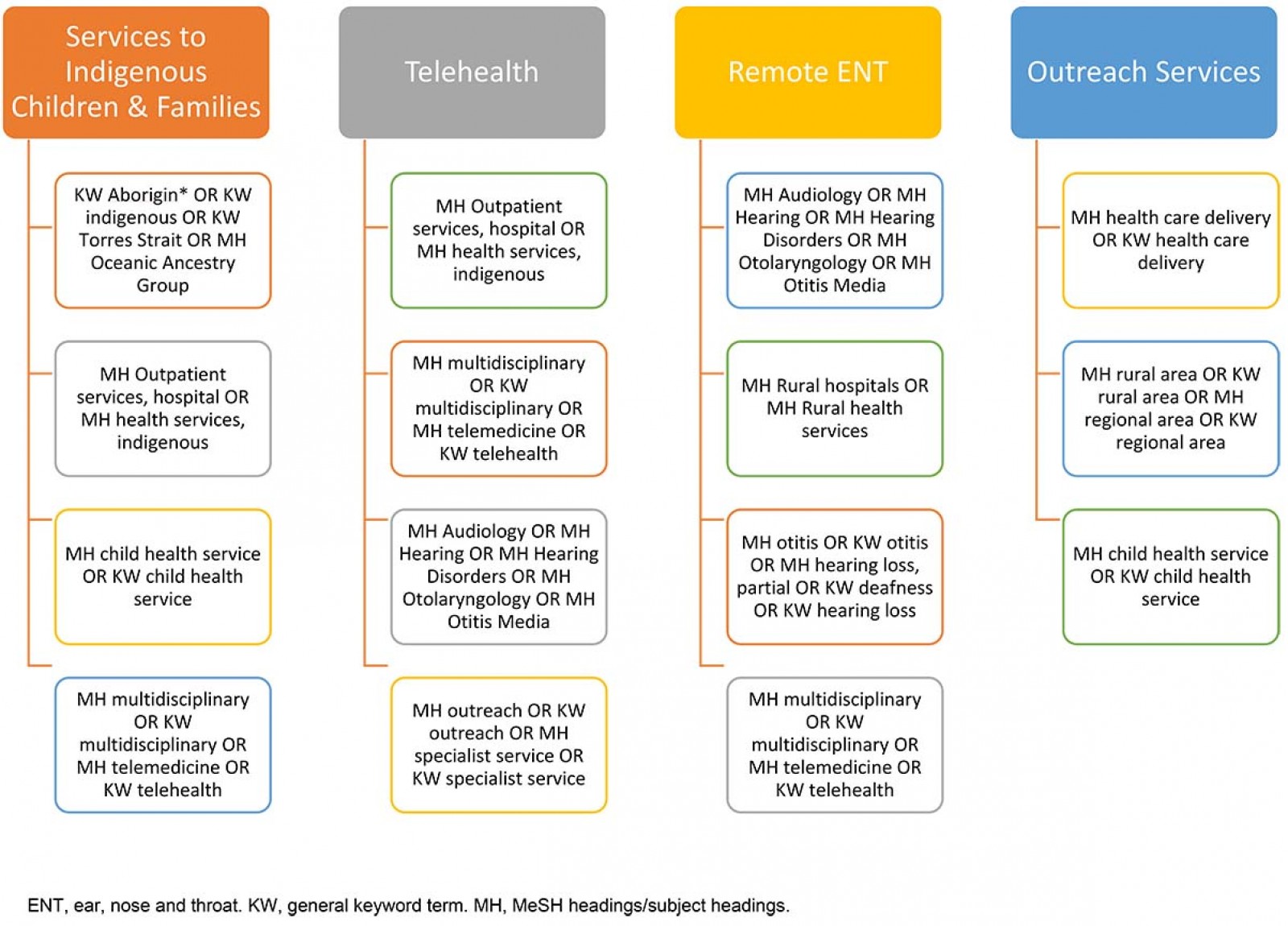

The search strategy was divided into four sections (A–D). It was anticipated that early sections (A–C) would inform remote ear (ENT) and hearing health service models (D). Figure 1 outlines the search strategy, prior to filtering off irrelevant abstracts and adding papers from the wider searches.

- Outreach services for rural and remote communities: searches 8 + 10 (AND 7) were combined

- Services for Indigenous children and families: searches 1 AND 3 AND 9 + 1 AND 3 AND 6 were combined

- The use of telehealth/telemedicine technology in service provision 3 AND 6 + 2 AND 6 + 6 AND 10 were combined

- Remote ear (ENT) and hearing health service models 2 AND 6 + 2 AND 4 (AND 5) were combined.

Figure 1: Outline of searches contributing to the final qualitative synthesis.

Figure 1: Outline of searches contributing to the final qualitative synthesis.

Study selection

After the removal of duplicates, the titles and abstracts of retained studies were screened for relevance. The entire search list was divided and reviewed by the first author (SJ). Any discrepancies were resolved by consultation with a research-led clinician. All citations were exported to EndNote X7 referencing software.

Inclusion criteria: The objective of the review was to examine service delivery models (routine and specialist care – outreach) for rural and remote areas, which may then be applied to a new ENT model of care in the Cape York region. Publications from countries known to deliver healthcare services to similar populations, such as Canada, New Zealand and the USA, were included. Research trials, reviews or evaluation studies, which described a current or revised service delivery method for ENT or other medical specialty areas (medical and surgical outreach), were retained.

Exclusion criteria: Service delivery models for palliative care and cancer, mental health or childhood development (special healthcare needs) and acute care management (including asthma, cystic fibrosis and epilepsy) were excluded. Papers describing clinical outcomes to research interventions, including antibiotic trials, that did not include components of outreach or service delivery were excluded.

Telehealth: Due to the vast volume of literature on telehealth, with several journals dedicated to only publishing on telehealth, this review only included telehealth studies limited to rural or remote service locations. ‘Models of care that used telemedicine have the potential to address specialists’ geographic misdistribution and address disparities in the quality of care delivered to people in underserved communities’10.

Synthesis of results

Summary tables were presented within each section as an easy-to-access format in order to avoid unnecessary repetition. The total counts of references within each section included the text and the table contents. Tables contained details of studies with particular interest. Extracted information included first author, year published, article title, description of model of care/article type, components required for success/sustainability, and components that negatively impact on success/sustainability. This review did not assess research outcomes, no quality appraisal of research methods. Material were included if deemed relevant by the research team following predefined criteria set by Queensland Health. A qualitative synthesis presents the findings of the review.

Ethics approval

As this study did not involve the collection of any patient data, an ethics exemption was granted by the Far North Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee, as a Quality Improvement Activity, reference number HREC/17/QCH/3-1111 QA.

Results

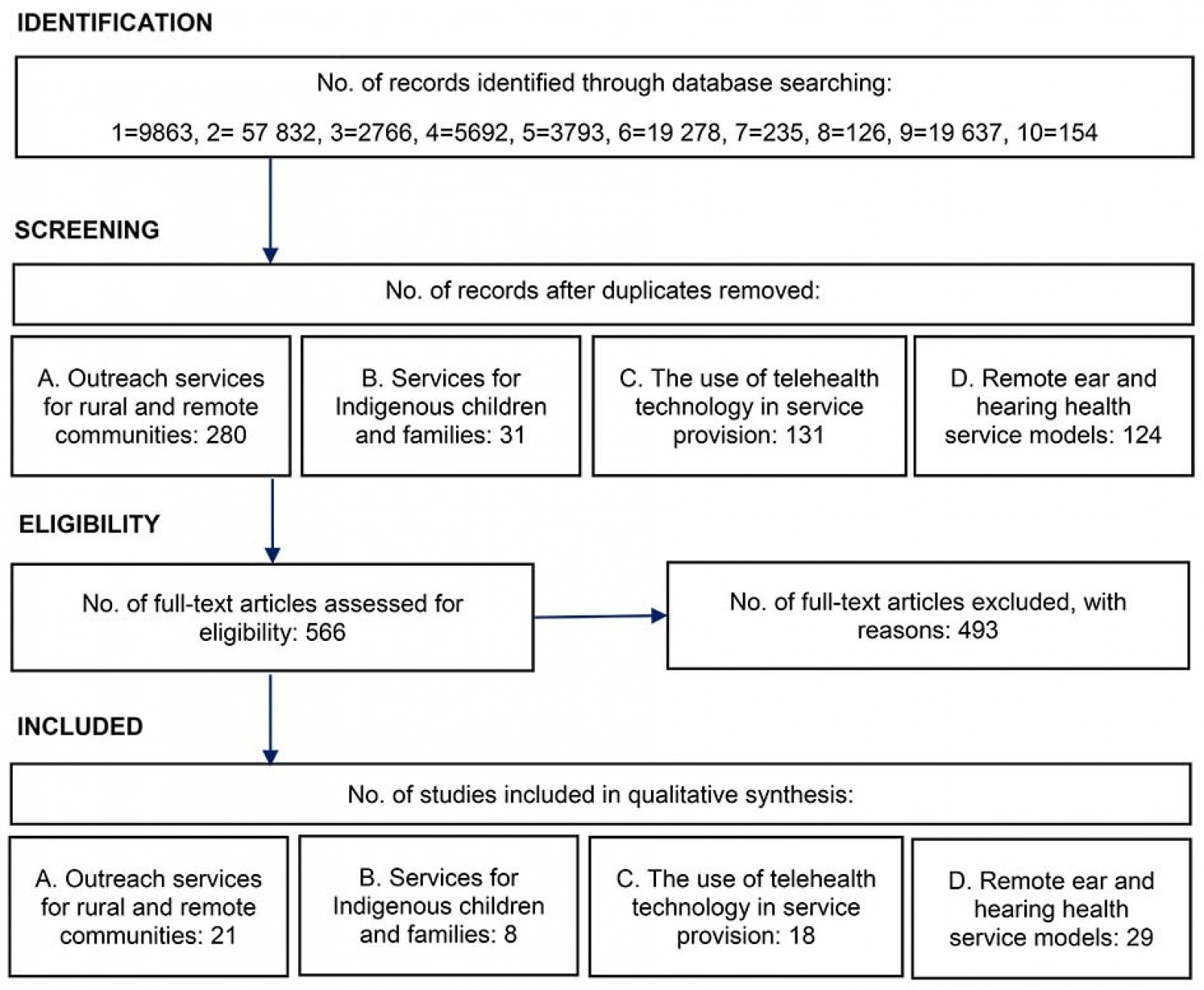

After removing duplicates, 566 full texts were reviewed for suitability. Some references overlapped into more than one category, leading to a final list totalling 71 references, including 21 references under outreach services for rural and remote communities category; eight references under services for Indigenous children and families; 18 references under the use of telehealth technology in service provision; and 29 references under remote ear and hearing health service models (Fig2).

Figure 2: Database search results.

Figure 2: Database search results.

Outreach service models for rural and remote communities

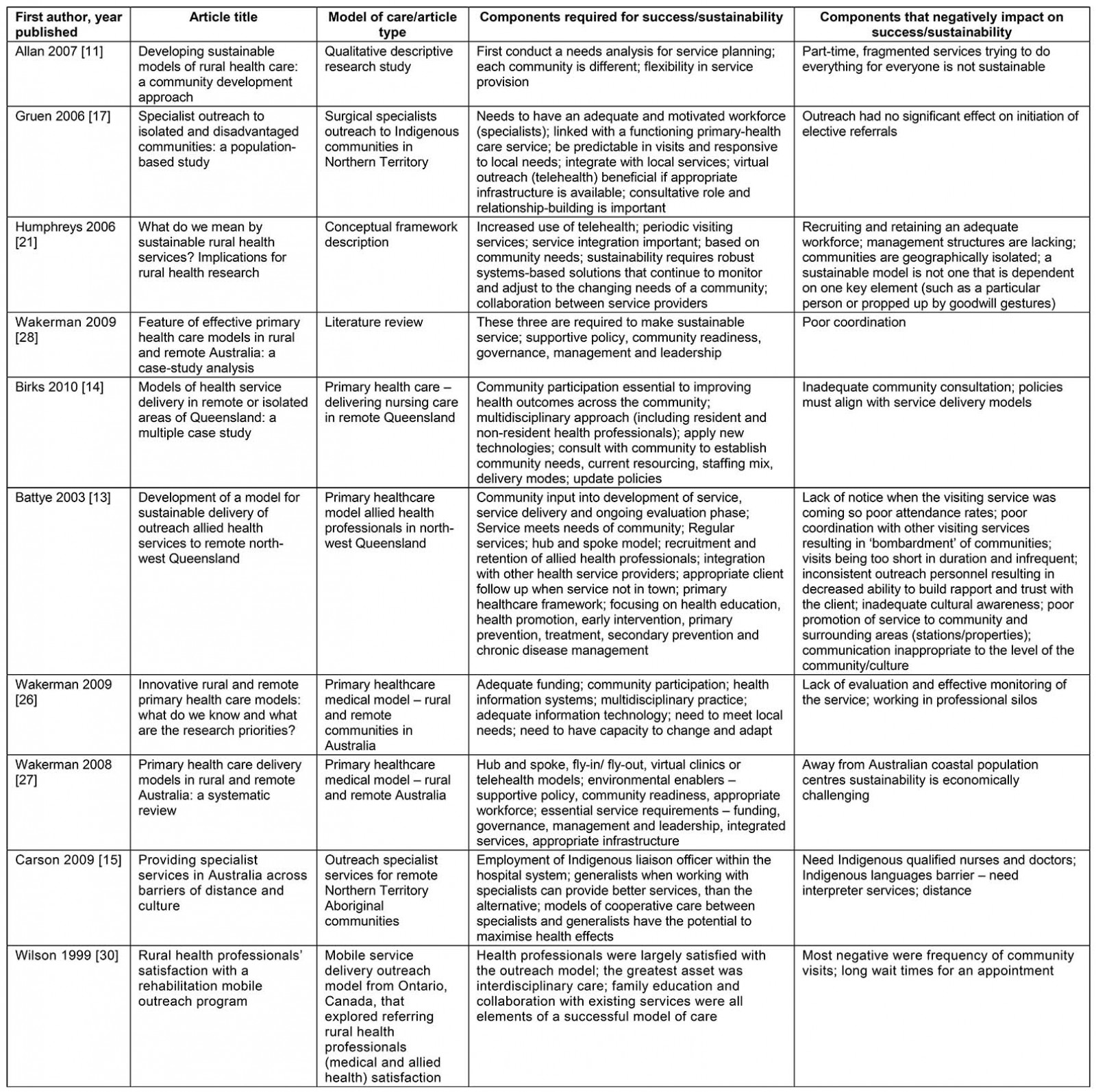

Outreach services are mobile clinics, or satellite services offered by a hospital. They usually provide specialist services at an alternative location aimed to improve access to specialist services. Outreach usually costs less to deliver than hospital outpatient clinics because fewer people are required to travel (O’Sullivan et al 2014)11. However, not all outreach models are successful: some have poor patient attendance and are therefore not cost effective. The search identified 21 publications11-31on successful and sustainable outreach services from rural and remote communities (Table 1).

Common traits that could lead to successful and sustainable outreach service delivery include appropriate policies, governance, leadership and funding to support the service; undertaking community consultation and participation when planning a new model; flexible and innovative service provision to meet local needs; integrated services that collaborate with existing service providers; services that are regular and predictable in nature; services that are multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary in approach; and utilising telehealth and emerging technologies to support service provision.

Table 1: Rural and remote outreach articles describing models of care12,14-16,18,22,26-28,30

Services for Indigenous children and families

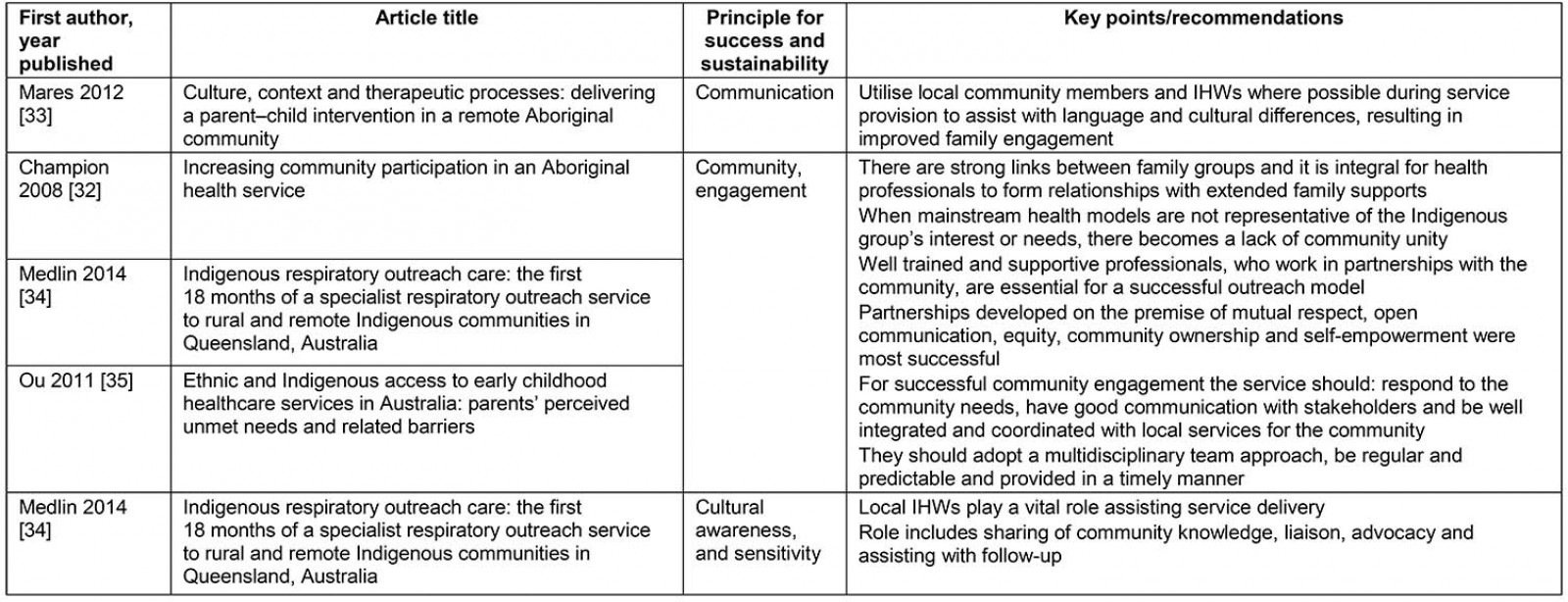

The benefits of providing outreach services for remote Indigenous children and families include less travel for patients and fewer disruptions to families, with an increased likelihood of higher attendance rates19,20. Outreach health services can address some of the barriers to access and inequitable service provision to Indigenous children and families19. Clinical specialist services offered in communities can increase extended family involvement in healthcare consultations18. The search identified eight publications18-20,31-35 describing success and sustainability of health service provision for Indigenous populations. Table 2 provides a summary of five selected studies identifying the principles of success and sustainability.

Sustainable and culturally safe models of care for Indigenous populations relies heavily on building positive relationships. Successful services are developed on the premise of respect with community ownership and self-empowerment as the goal, which are best described as ‘partnerships’: between family groups and health services, between health professionals and community, between health services providers from different primary health agencies. Partnering with local Aboriginal health workers was considered essential for a successful outreach model.

Table 2: Outreach health services delivering services to Indigenous children and families32-35

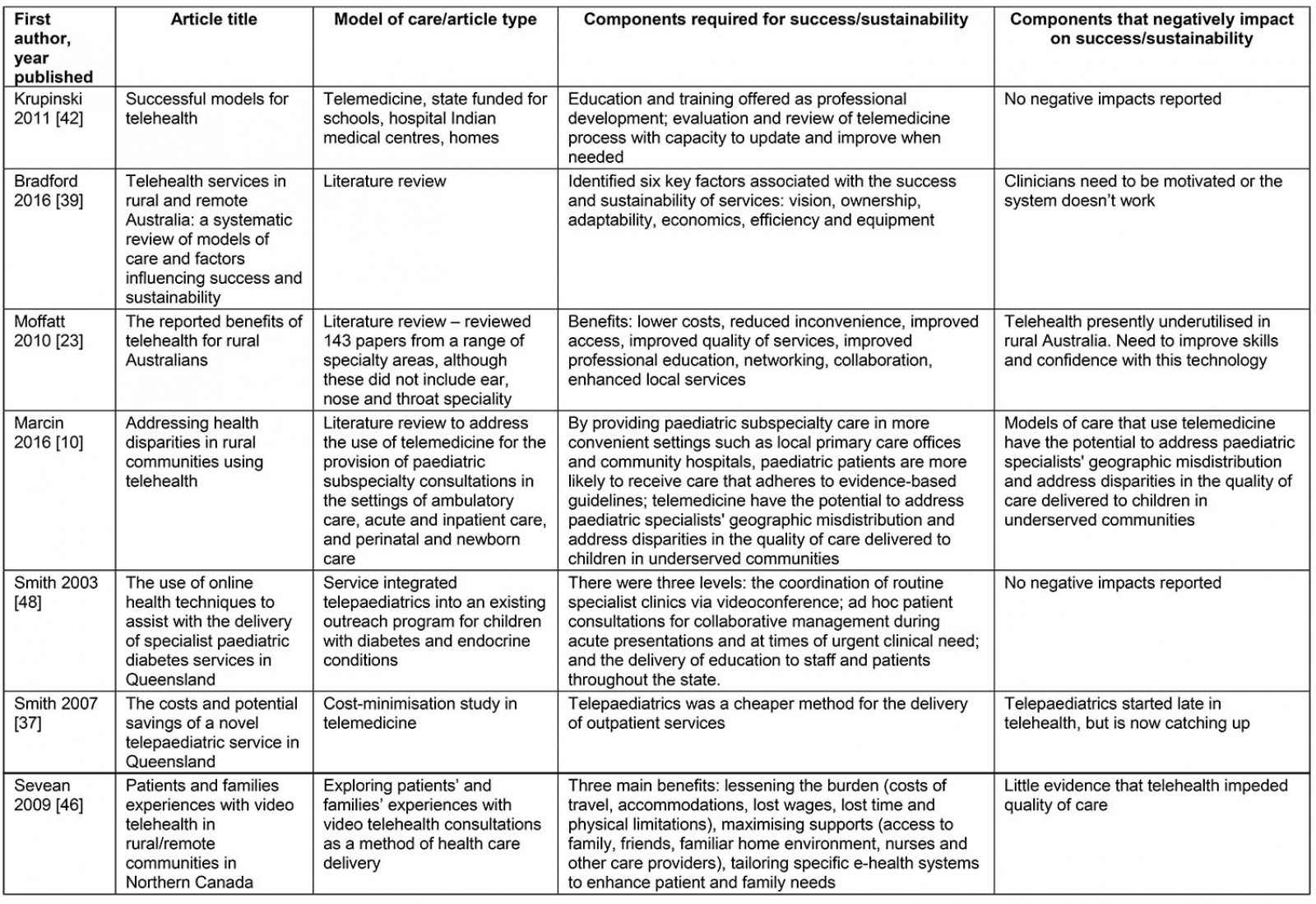

Use of telehealth/telemedicine technology in service provision

Telehealth/telemedicine has become an increasingly viable solution addressing resource limitations, workforce shortages and geographical barriers that affect service delivery in rural areas36. It supports provision of speciality consultation for patients within their own community, while facilitating care that is more accessible, family centred and coordinated with local service providers10. Throughout rural and remote Australia, distances between regional centres and remote communities are often considerable; under these conditions telehealth/telemedicine offers an alternative method of delivering services37. This review identified 18 publications10,24,31,36,38-51 reporting the use of telehealth or telemedicine, which can offer insight into a remote Cape York service delivery model (Table 3).

When costed, the telehealth model of service delivery reported savings of A$600,000 (combining fixed and variable costs over a 5-year period) compared to face-to-face service delivery51. Other benefits of telehealth include facilitating continuing medical education, contacts with peers, and access to a second opinion, which is known to foster the retention of local expertise41.

Telehealth and telemedicine services are recognised nationally and internationally as cost-effective service delivery methods; other benefits include improved patient outcomes, reduced costs and time, and reduced carbon impacts10,37-40,44,47,49. Although most reviewed studies reported on the benefits to service providers, including cost savings, a few studies concentrated their focus on patient and family experiences with telehealth. One study from remote northern Canada identified many benefits to families: lessening the burden (costs of travel, accommodations, lost wages, lost time and physical limitations), maximising supports (access to family, friends, familiar home environment, nurses and other care providers), and tailoring specific health care to patient and family needs, such as male and female household responsibilities46. Interviewees in this study considered that these combined benefits improved their quality of life and made accessing health care easier and more convenient. For patients, telehealth/telemedicine lessens the burden of health for patients and families in rural communities because it opens up patient choices.

Table 3: Selected telehealth/telemedicine service models10,24,37,39,42,46,48

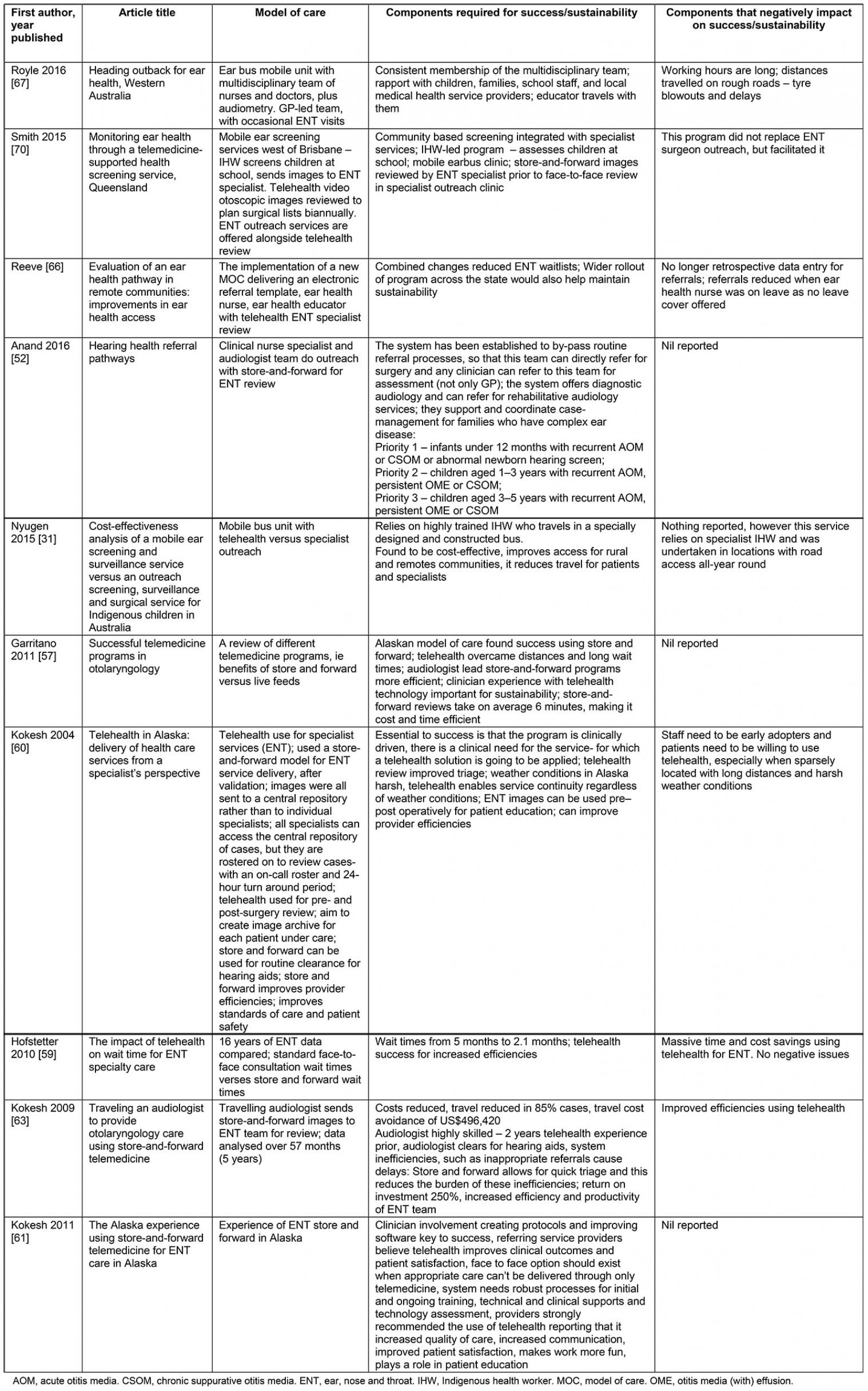

Remote ear and hearing health service models

Outreach services offered in rural and remote areas report the importance of a multidisciplinary team for ear and hearing health service delivery. The search identified 2910,31,38-40,44,47,49,51-71 publications reporting on ENT outreach, including the use of telehealth within outreach models (Table 4). Most literature found that the team needed to comprise an ear health educator or specialist nurse plus an audiologist52,67,71. The most comprehensive team worked on the Western Australia Earbus mobile health clinic, employing an audiologist, a GP or nurse practitioner, an ENT nurse educator, a nurse audiometrist and a data collection officer67,71. Smaller staffing models offered routine outreach from a clinical nurse specialist with an audiologist52. Most outreach models only offered direct ENT service delivery via telehealth52,66. Smith et al presented an outreach model with visiting ENT surgeons plus telehealth reviews68,70. The literature also identified a tendency towards the use of store-and-forward telemedicine over live video. As argued by Kokesh et al (2011), store-and-forward telemedicine allows greater flexibility and convenience for both the sender and the receiver. The sender can collect images and clinical information from the patient without the ENT specialist being physically present61.

Studies from remote locations nationally and internationally report the benefits of telehealth or telemedicine for reviewing ENT patients, including benefits for patient outcomes, reduced costs and time, and reduced carbon impacts56. Further, a telehealth scoping study identified that face-to-face consultations for ENT consultations could be reduced by 89% if telehealth were used appropriately53.

Table 4: Selected ear, nose and throat models of service delivery31,52,57,59-61,63,66,67,70

Discussion

This rapid review, undertaken to inform the development of a new sustainable, evidence-based model for future ENT services, provides a synthesis of evidence for what works to deliver remote outreach services. Findings indicate that sound and sustainable outreach models build on existing services; they have the capacity to be tailored to local needs and to promote cross-agency collaboration. The review identified a number of essential characteristics of successful sustainable outreach services, including a flexible, multidisciplinary and well-integrated team with existing service providers. Further, services for Indigenous people need to be developed on the premise of respect, best described as ‘partnerships’. Employment of local Aboriginal health workers is considered essential for a successful outreach model. Outreach services that offer interdisciplinary assessment and collaboration were found to be highly valued by health professionals29.

Presently, specialist services are offered across the state using three methods: patient travel, outreach clinics and telehealth17,29. For a clinician, the most conventional service method is for the patient to travel; however, the costs required to support this model are approximately A$54 million per year (2012)21. However, hospital administrators advocate for specialist outreach clinics in rural and remote areas that are supported by or replaced by telehealth services21,29. Telehealth services have been shown to be adaptable to the needs of patients, clinicians and health services; they are cost effective and often much more efficient than the alternative face-to-face services. While some literature recommends that telehealth should not completely replace traditional clinician–patient relationships18, others suggest it is a step forward and is a technology ‘we need to embrace in this day and age’24.

There are limitations to this study, including that this review was conducted as a ‘rapid review’ rather than a systematic review; as such it is possible that some literature was missed. However, this study did employ a rigorous search strategy developed by an accredited librarian to reduce the impact of this. Also, this review did not assess research outcomes or quality appraisal of research methods; materials were only included if considered relevant by the research team.

Conclusion

The evidence generated from this rapid review highlights a number of traits for successful and sustainable ENT service delivery in rural and remote areas, specifically, the literature advocated for the employment of a dedicated ear and hearing health educator (nursing), outreach nursing and audiology, and supported ENT access using telehealth41. Services need to work in collaboration with existing services and offer respectful partnerships within communities and, where possible, offer ongoing education to local health workers who support the outreach team when in community.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Kate McConnon, then Executive Director of Medical Services Torres and Cape York Health Service, who enthusiastically supported this initiative. They also thank the Clinical Excellence Division of Queensland Health for their support and providing the funding to deliver a new ENT service delivery model for ear and hearing health across Cape York. We wish to thank Queensland Health librarian Juliet Marconi for assisting with the search strategy applied in this review. Lastly, thanks to CheckUp Queensland for supporting remote access to ENT services for Cape York children.

references:

You might also be interested in:

2011 - Parkinson's disease in regional Australia

2011 - Causes and circumstances of death in a district hospital in northern Cameroon, 1993-2009