Introduction

Access to health care as near to where people live as possible is desirable but is problematic for some, especially those who live some distance from larger towns and cities. A contributing factor to limited healthcare access in rural communities is that not enough medical graduates choose to work in rural and regional areas, especially in general practice. Recruitment and retention of the rural medical workforce is problematic internationally1, possibly due to the pressure of high health and social needs of rural communities, after-hours care, perceived low reward and lack of collegial support2. In New Zealand (NZ), there is a need for an estimated 50% of medical graduates to work in General Practice. However, one study found that only 29% of students close to graduating declared a strong interest in this career choice in NZ3. A recent study also found that as few as 16.4% of general practitioners working in rural areas were educated in NZ4.

Background

The career decisions of recent medical graduates are known to be affected by a variety of factors, including: the way health career choices are viewed by society; financial incentives; availability of professional development and career opportunities; availability of locum positions; availability of work–life balance; and lifestyle choices determined by their spouses and family needs1. International studies indicate that selecting students for their interest in rural medicine and/or with rural backgrounds, enabling positive learning experiences in rural areas, and supporting career pathways in rural practice increase the intention of medical students to work in rural communities upon graduation1,5,6.

Concern about rural recruitment has resulted in the establishment of programmes providing rural experience in Australia, USA, Canada, the UK and other places, as well as NZ. In NZ, as in other countries, recruitment of medical practitioners to rural areas is a Government priority. A critical review7 of interventions to address the inequitable distribution of healthcare professionals to rural and remote areas found strong evidence for selecting students from a rural origin (especially those attending a rural primary school) and who intended at the outset of study to practice rural medicine. Provision of more accommodating conditions for women in rural practice was required to balance the gender difference for men being more likely to practice rural medicine. Further, moderate evidence was found for students being more likely to adopt rural practice following a programme that included immersion in rural clinical practice. Students are known to do as well, if not better, academically through these programmes8-11.

Immersion in rural clinical practice facilitates hands-on experience of five interlinked concepts found to be central to an understanding of rurality and rural practice12. Thus, medical programmes have been encouraged to include opportunities to experience (1) rural–urban differences in the nature of the population and health problems encountered; (2) reduced access to and choice of services offered; (3) less anonymity and fast flow of information in rural areas; (4) cultural safety that accounts for individual needs and identity; and (5) that teamwork is vitally important in the management of health care in rural areas.

Established in 2008, the Pūkawakawa Programme is a year-long regional and rural experience for 24 selected Year 5 students per year from the University of Auckland‘s Medical Programme in partnership with the Northland District Health Board and two Northland Primary Health Organisations. The original curriculum was described by Poole et al.13 and remains essentially unchanged. The curriculum is delivered alongside the standard curriculum with the same learning outcomes and assessments. The main structural differences are a 7 week integrated care/GP attachment in a small rural community (compared with 2 weeks of general practice attachment in the standard curriculum) and a 10 week interlinked woman and child health attachment. Students have a secondary care experience similar to the standard curriculum, including psychiatry and specialist surgery. The features of the learning experience in Pūkawakawa include greater continuity in their clinical experience, greater exposure to undifferentiated presentations and a wider range of pathology. Being part of a small team allows greater responsibility and more opportunity to perform procedures. Students also work more closely with their senior colleagues and report feeling more supported in their clinical experiences than those in the standard curriculum. In their rural attachments, they are involved with local communities and get to experience the issues of delivery of care in those communities. Students also engage with Māori (indigenous people of NZ) in different settings, which provides opportunities to improve Te Reo (language) skills, cultural safety and knowledge of Te Ao (the Māori way). They live on the hospital sites and this encourages shared learning and facilitates after-hours work.

Of the students who took part in Pūkawakawa between 2008 and 2015, 23% have returned as first-year house officers and have taken 40% of the available first-year positions over that time. A mixed-methods evaluation of the first year of the programme found high levels of student and teacher satisfaction and similar academic performance to students in the standard program13 but at the time of publication, it was too early in the programme to identify changes in students’ career aspirations. A postal questionnaire examining the workforce intentions of Pūkawakawa cohorts between 2008 and 2011 demonstrated that of the respondents, nearly two-thirds were working in regional or rural areas and general practice was one of the top three intended careers14.

An area explored but not completely resolved in the literature concerns the factors that influence medical graduates’ uptake of rural and regional careers15. Australian studies suggest that drivers for taking up a regional or rural career are a rural background6,16 and an experience of a lengthy rural clinical attachment6,17, or by the influence of their interactions with preceptors3. In one study, almost twice as many students from a rural background and/or training worked in regional centres6. An earlier survey indicated that participating in the Pūkawakawa Programme confirmed the students’ pre-existing intention to work in a regional or rural area and highlighted the importance of work–life balance. Importantly, some students indicated that the experience had led them to change their views to a positive consideration of working in a regional or rural area14. What is not clear is the interplay of these and other drivers of the decision to pursue a career in a rural area or otherwise. Also less clear are the influences on uptake of careers in a regional hospital as distinct from than uptake of other rural careers. Therefore, in this study we explored the influences that have led students in the Pūkawakawa Programme to return to the regional hospital in the Northland District, NZ, as resident medical officers. We also identify their career intentions and the factors that have influenced and are likely to continue to influence those choices.

Methods

A mixed-method, descriptive design was used to explore factors that encouraged or discouraged junior doctors to return to employment in a regional hospital where they had completed the Pūkawakawa Programme. Methods involved the completion of a short survey, followed by participation in a focus-group discussion or a one-on-one semi-structured interview using a standard set of questions. Ethics approval (Ref. 9890) was gained from the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee and permission to conduct the study on site was given by the Northland District Health Board. Data collection occurred between September 2013 and August 2014.

Purposive sampling was used to access and invite participation from junior doctors, all of whom had completed the Pūkawakawa Programme as students. Some of the junior doctors were employed at the time of the study by Northland District Health Board in their first and/or second year after graduation. A counter view was sought from students who had elected not to return to Northland District for early career employment. This counterpoint view was thought to be important to provide some balance to the expected positive perspectives of those who had returned to the region in which they experienced the Pūkawakawa Programme. Snowball sampling was used to invite participants who had not returned to Northland. Typically, data saturation has been found to occur with 12 participants in qualitative studies of this nature18. Therefore recruitment of at least this number was intended.

Survey

All participants agreed to complete a short survey with brief demographic items and were asked to rank their reasons for applying to undertake the Pūkawakawa Programme and to either return, or not, to Northland for early career employment.

Focus groups and interviews

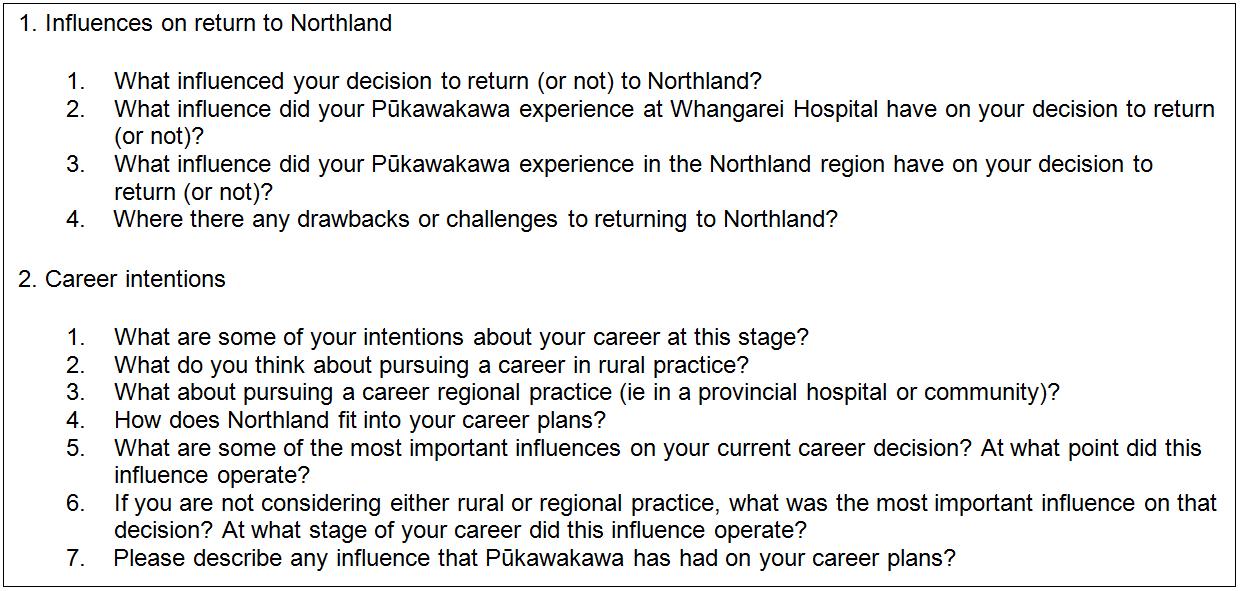

Focus groups were held to gain a better understanding of the factors influencing participants’ decisions to return (or not) to Northland. Focus groups were facilitated by a member of the research team on site and were audio-recorded and transcribed (AM). The focus-group questions (Table 1) were the basis for open questions and prompts were used to generate further clarification and explanation. The mean length of time for focus groups was 44 min (range 33–53 min). Individual interviews were held with those who had not returned to Northland because it was not feasible to bring them together from different regions as a focus group. One interview was face-to-face and three were held by phone. The mean length of interviews was 25 min (range 13–33 min).

Data analysis

Survey data were summarised and tabulated to describe the baseline characteristics of the participants, including their first, second and third choice of location for employment in the first 2 years following graduation. Focus-group data were analysed using nVivo 10 software (QSR International; http:www.qsrinternational.com) using a general inductive method19. Two researchers independently analysed data and agreed on the themes generated.

Table 1: Focus group and interview questions

Results

Survey

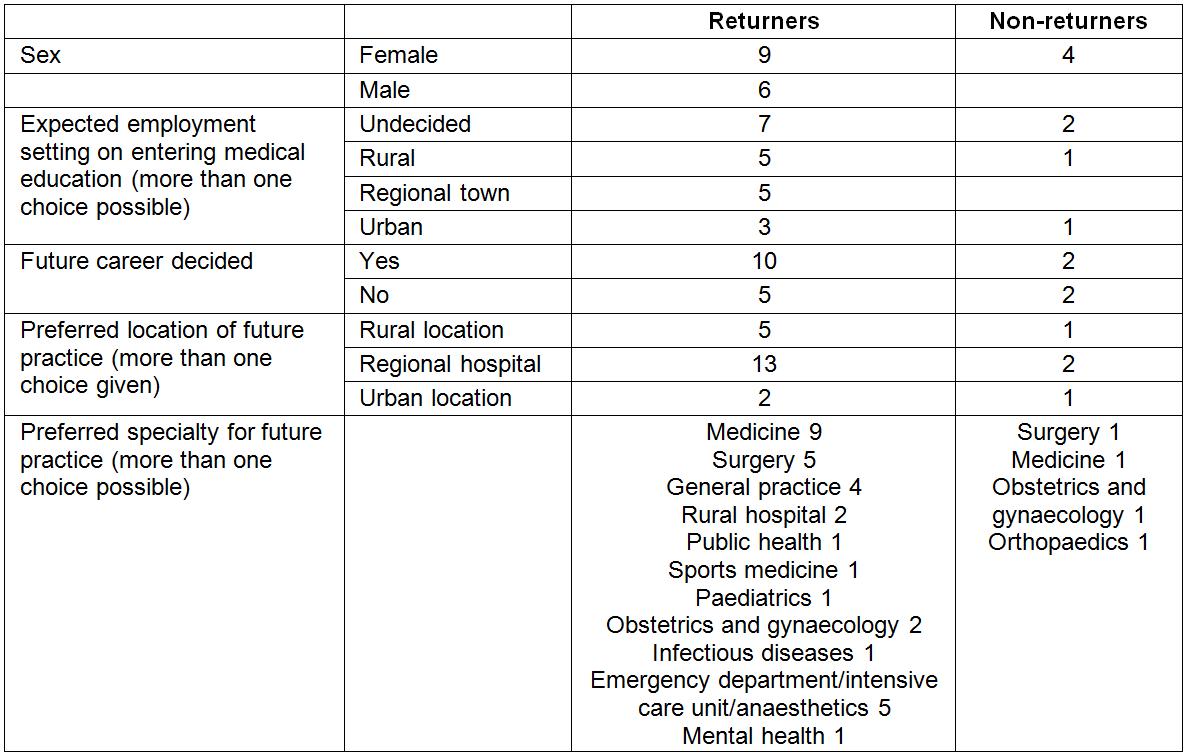

There were 19 participants, 15 who returned to Northland and four who did not. All completed a short survey prior to participating in a focus group (returners) or interview (non-returners). Ages ranged from 23 to over 30 years. Even though the invitation to participate was disseminated widely, we were able to recruit just one Māori participant, and none of Pacific Island descent. Table 2 indicates that those who were brought up in a regional or rural setting, but attended an urban secondary school, expected (at the beginning of their medical education) to practice in a regional or rural setting and that choice endured at graduation in the preferred specialty areas of medicine, surgery, emergency department, intensive care or anaesthetics.

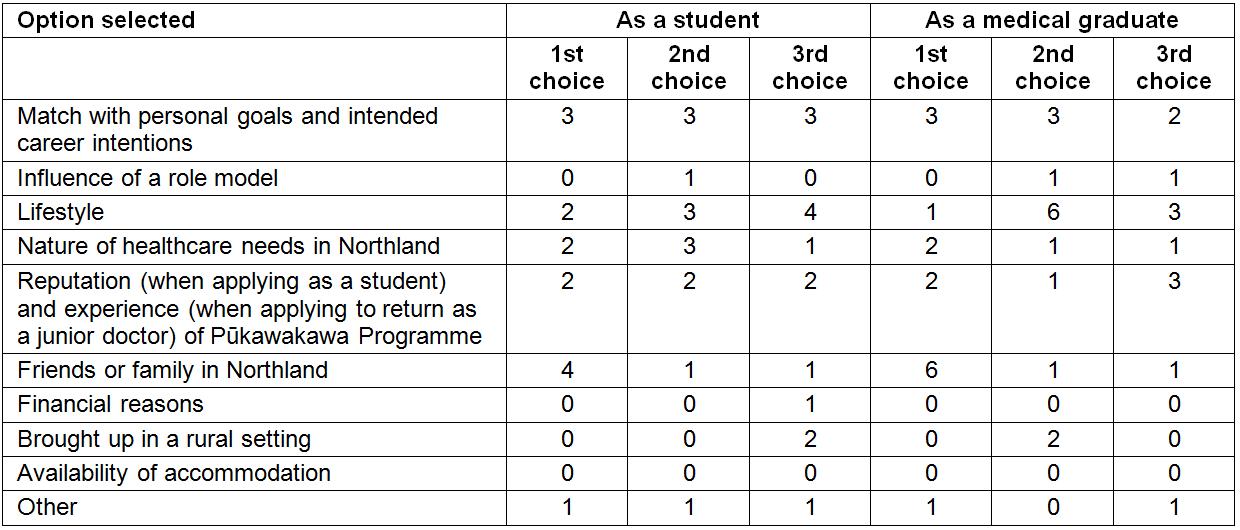

The reasons that junior doctors ranked most highly for having applied to undertake the Pūkawakawa Programme were markedly similar to the reasons that they selected for their return to Northland for early career employment (Table 3). The highest number of participants ranked the item 'Match with personal goals and intended career intentions' as their first, second or third choice and this was at both time periods, indicating that coherence of personal and professional goals endured over time. Other most frequently selected reasons that were consistent when applying for Pūkawakawa and, later, for employment as a graduate were the lifestyle available in the region, that they had friends and/or family in the area, and the reputation and experience of the Pūkawakawa Programme. When applying for the programme as a student, the reputation of the Pūkawakawa Programme ranked highly, and when returning as a junior doctor, their experience of the programme was also a positive influencing factor. Some options offered were either not selected or seldom selected as reasons for their decisions, and these were consistent across both time periods. These included the availability of accommodation in Northland, having been brought up in a rural setting, financial reasons and the influence of a role model. Just one option, the nature of healthcare needs in Northland, was ranked differently by junior doctors (as a reason for returning to Northland District) than by students (as a reason for applying for the Pūkawakawa Programme).

The four participants who did not return to Northland in their first and/or second post-graduate year selected personal goals and career intentions as important reasons for applying for the Pūkawakawa Programme and three also ranked this as an important reason for not returning, suggesting that their goals had changed. The influence of friends and family had not been a reason for three of the students for applying for Pūkawakawa, but this was selected as a reason for three of them deciding not to return to Northland. The reputation of Pūkawakawa was an influence on applying for the programme for three participants, but the experience of the programme was not ranked as a reason for non-returners. The nature of healthcare needs in Northland District was selected both as a reason for applying to Pūkawakawa and also as a reason to not return.

Table 2: Baseline characteristics of participants

Table 3: Reasons given for having applied to undertake the Pūkawakawa Programme as a student and later return to Northland District as a junior doctor

Focus groups and interviews

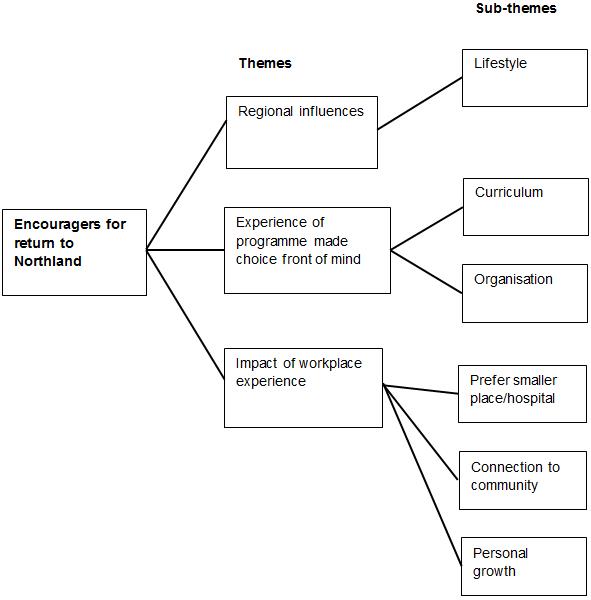

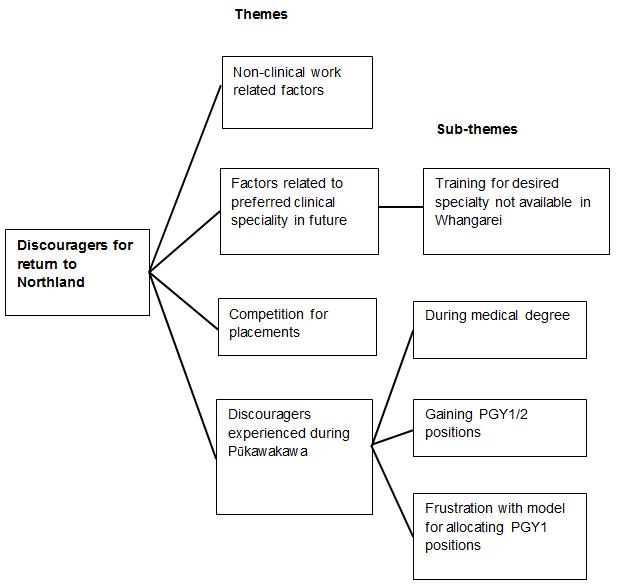

Fifteen participants who returned to Northland District for employment participated in focus groups and four who did not return were interviewed. Qualitative data provided further valuable explanation of the influences on participants’ decision-making about their career choices and enabled a deeper understanding of some of the issues raised in the brief survey. The encouragers and discouragers for returning to Northland for future employment and the relevant influences on participants are presented below with selected exemplar quotes from transcripts. Figures 1 and 2 summarise the themes and sub-themes emerging from our inductive analysis and the complete set of thematic results, including individual coded items, are available in a Supplementary File.

Figure 1: Themes and sub-themes for factors that encouraged participants to return to Northland District.

Figure 1: Themes and sub-themes for factors that encouraged participants to return to Northland District.

Figure 2: Themes and sub-themes for factors that discouraged participants to return to Northland District.

Figure 2: Themes and sub-themes for factors that discouraged participants to return to Northland District.

Encouragers for returning to Northland District

Factors that encouraged participants to return to Northland were to do with the nature of the region, their experience as learners in the Pūkawakawa Programme and also the support and experience offered during clinical placements.

Regional influences

Those who returned to Northland, and also those who did not, spoke positively about the Northland region and the lifestyle it enabled. For some, the attraction was for a smaller, non-urban environment.

[I prefer] to be in a smaller place. I’m from the middle of nowhere, from a rural background. I’ve been a farmer most of my life (Interviewee 3).

You can afford a nice house with more land in a smaller town [and] you have more time to spend with your family (Interviewee 1).

The outdoor lifestyle and coastal environment was a drawcard for some participants, with lifestyle benefits an important motivator to return to Northland.

In summer you can get to the beach and have 5 hours at the beach before it gets dark (Participant Focus Group 3).

… surfing and mountain biking versus what you might have elsewhere (Participant Focus Group 1).

For others, familiarity with the region was an attraction to return to where they had grown up.

I’m from up here and I grew up here so that was a strong pull for me (Participant Focus Group 1).

Finally, the pattern of the roster for days at work was more attractive than for other regions because it provides for longer periods of time off to enjoy what the region has to offer.

Whangarei is one of the only few DHBs [District Health Boards] that has the ten in four roster [10 days on duty followed by four days off] (Participant Focus Group 1).

… having loved the lifestyle, that you could actually experience [it] in that roster (Participant Focus Group 1).

Experience of the programme made the choice front of mind

The experience gained during the Pūkawakawa Programme was mentioned by returners as a positive influence on their decision to return to Northland District, both in terms of the way the curriculum was organised and also the influence of their clinical experience within the host organisation. There was agreement that the programme as a whole was a strong encourager for returning to Northland District. Examples include the following.

If I hadn’t come up here in the fifth year then there is no way I would have moved up here (Participant Focus Group 2).

I'd have to say that it was a hundred percent the Pūkawakawa Programme made me come back (Participant in Focus Group 3).

Returners also spoke positively about the curriculum and of being challenged to learn.

I learnt so much being up here as a Pūkawakawa student, … like what you're learning was really rewarding (Participant Focus Group 3) and

I think the best way to learn is being pushed to think for yourself and they really did that here (Participant Focus Group 4).

Returners mentioned that there was novelty and enthusiasm for teaching that may not be experienced in larger centres where there are many more students and clinical teachers may lack such enthusiasm.

They gave you tips, were really enthusiastic about teaching (Participant Focus Group 4).

Lack of student fatigue, feeling valued (Participants Focus Group 2).

Returners also spoke about having many more opportunities to learn clinical skills and procedures as students in the programme and were included in decision-making discussions.

[We got to] do more procedural things and [to get] involved in decision-making (Participants Focus Group 3)

The programme played a role in the making of future career decisions through clinical experience in a range of clinical settings and living in various community settings.

I think Pūkawakawa confirms what I wanted to find for myself in a medical career. It was much more obvious that that was the kind of life that I wanted to live and that was the career path I wanted to follow (Participant Focus Group 4).

An obvious drawcard for returners was the warm and supportive relationships formed during the programme with those in the host organisation through clinical learning experiences. The size of the hospital and the provincial nature of the surrounding township were seen to encourage collegiality and to make living in a smaller town seem possible, even if that had not been considered before. Examples include the following.

We had a real connection with the house officers who were here, many of them who were returning Pūkawakawa students [that] added more to the experience (Participant Focus Group 1)

By the end of it you knew everyone in the hospital, the area around the hospital, and you started to meet people who are a step removed from the hospital. You just start to get a bit more feel for living somewhere like that… and I certainly can see attractions (Participant Focus Group 1)

It’s a small place and everyone knows your name but also that all the consultants were really nice and approachable (Participant Focus Group 3).

Clinicians who mentored and taught those who had returned to Northland District while they were students in the programme were seen as positive role models for a future career in Northland District.

… some really, really skilled clinicians who were great role models… I want to be a doctor like that, … a lot more viable in terms of a career pathway (Participant Focus Group 4).

Impact of workplace experience during the programme

Participants were clear that working alongside clinicians during the programme positively influenced their intention to return to the region after graduating because their experience enabled anticipation of:

More variety and more autonomy

Definitely a lot here career-wise and

The doctors that work at Whangarei Hospital seem to be actually fulfilling a doctor’s role in the traditional sense more than super-specialists do (Three participants in Focus Group 4).

Their preference for working in a smaller, regional hospital was expressed clearly by participants as a reason for their return, for example:

I think wherever I end up working permanently will be I want to work in a smaller hospital (Participant Focus Group 1) and …like this hospital or even smaller (Participants Focus Group 1).

Another participant was keen to avoid large urban hospitals that seem more impersonal and where students seem to lack individual attention.

… very big teams … much more faceless (Participant Focus Group 2).

Having a connection to a community in the region was a positive influence for returning. One non-returner would like to have returned because of being raised in the area and commented that:

Lovely that it’s in my hometown (Interviewee 4).

Community connections were also built through concern about the health inequity that people face. Important learning was gained through community-based experience in which students had opportunities to witness living conditions that they had not seen before and that helped them appreciate first-hand the health implications of poverty. These experiences were, for some, an important influence on their desire to provide care for this population and an influence to return to Northland. Comments that demonstrate this are:

The extreme poverty, extreme situations and un-wellness in this area, and the type of healthcare that we’re providing. On home visits that I went on with the GP, just the genuine state of poverty gave you the ability to actually understand the presentations that you are seeing back at the hospital. There’s a huge need for health intervention and primary health care and research into why we’re not making much headway into those issues, another influence for me to come back (Participant Focus Group 1).

… a different appreciation for how people live, that you really don't realise unless you actually go their house and see how cold it is, or how many kids there are, how few toys they have (Participant Focus Group 3).

you can imagine the house that they live in and the problems they would face around just getting a meal on the table, or keeping everybody warm, or taking their new-born baby home (Participant Focus Group 3).

Others felt connected to the community and would probably continue to work in rural settings because of how much they were appreciated by members of the community. Comments that illustrate their appreciation of how well students were received and that doctors were integrated into their communities include:

… just stoked to have you up here (Participant Focus Group 2).

[Doctors] seem to be very much entwined in the community and living as part of the community (Participant Focus Group 4).

The desire to contribute to health gains more generally and to be personally challenged to be accountable to the populations they serve was a drawcard for some. Examples of such findings include:

…we could actually effect change beyond our own personal practice (Participant Focus Group 1).

... challenged to be the same person at work as I am at home and in the community … accountable to my community as well. I really value that (Participant Focus Group 5).

Discouragers for return to Northland District

Factors that were discouraging for participants as they decided whether to return to Northland District included non-clinical work-related factors, their intentions to undertake training in specialty areas of practice, competition to win a postgraduate position in Northland District and experiences that they had encountered during the Pūkawakawa Programme.

Non-clinical work-related factors

Many participants found decisions about future careers and where to settle challenging and unpredictable at this stage, for example:

So I think it is dependent on the whole situation … so it’s really tricky to say now what we’re gonna do when we don't know where our situations will be (Participant Focus Group 3).

For some participants, having a partner elsewhere was a discourager for returning to Northland.

I had a partner in Auckland who I met half way through the Pūkawakawa Programme and then I was in Auckland for my TI year so we were living quite close. So living apart from him again was a con (Participant Focus Group 1).

For others it was the distance from family and friends that discouraged them from returning to Northland District. One participant said:

I'm thinking about moving back to Auckland just because I miss my friends (Participant Focus Group 2).

Factors related to preferred clinical specialty in future

Some participants worried about their ability to gain entry to vocational training schemes if they stayed in Northland District.

The most important influence is actually getting onto the [specialty] training scheme. It depends what sort of sub speciality you’re involved in and [that determines] where you’re going to live and probably family and lifestyle (Non-returner interviewee 1).

Competition for placements

Some participants were discouraged by the complexities of the recruitment process for first-year positions.

Yeah, I think there’re difficulties between DHB expectations, college training expectations, university expectations, RMO [resident medical officer] expectations... (discussion among Focus Group 3 participants).

Others were discouraged by the perception of competition for first-year places in Northland District:

The likelihood of you getting a job up here is pretty slim (discussion among Focus Group 3 participants).

Discouragers experienced during Pūkawakawa

A few participants were discouraged by their Pūkawakawa experience and found this was a detractor to returning.

Pūkawakawa did the opposite of the intended for me on our rural GP placements. It was a little bit too intense for my liking (Participant Focus Group 2).

Factors that were discouraging for participants as they decided whether to return to Northland District included non-clinical work-related factors, their intentions to undertake training in specialty areas of practice, competition to win a postgraduate position in Northland, and experiences that they had encountered during the Pūkawakawa Programme. Figure 2 depicts the themes and sub-themes identified from data.

Discussion

The present study is the first time that graduates of the Pūkawakawa Regional Rural Programme have been interviewed about their reasons for returning to practice in Northland District. The study provides an in-depth view of the factors that influenced decision making. The most important factors that contributed to students returning to Northland District were a combination of the lifestyle experience while being a student together with their learning in regional and rural settings. That students who had a family connection to Northland District were more likely to return to Northland is no surprise and is consistent with other findings that students from regional and rural backgrounds are more likely to return to work in regional and rural settings20-28.

Which groups of students, those from a regional or rural background or those without such a background, should participate in regional and rural programmes is an often-debated subject, even though regional and rural programmes, at least in our setting, are consistently oversubscribed by two to one. The survey findings are consistent with strong evidence7 for continuing to select into the Pūkawakawa Programme students from a rural origin and who intend from early on to practice rural medicine. There is also consistency with moderate evidence7 for students being more likely to adopt rural practice following a programme that includes immersion in rural clinical practice. Our findings do not contribute to the evidence7 regarding whether more accommodating conditions are required for women in rural practice and this requires further research. However, on the basis of our findings, there is also an argument for students from all backgrounds to participate in regional and rural programmes. In a small number of students, the experience in the rural clinical learning environment proved 'too intense' and they decided against wanting to work in regional or rural areas. However, even for these students, they will recall what it is like to work in a regional or rural area and this insight will be helpful for future practice and interactions with doctors who may be referring patients from a rural area to an urban area.

Importantly, the study also confirms the value of the Pūkawakawa Programme and the clinical learning environment in helping students to decide where to work. In the years 2010–2016, those returning to Northland District as a percentage of employment places available increased from 30 to 61%. Similar to the findings of a large US study29, and a systematic review of interventions to address unequal distribution of health professional in rural areas7, not only did the experience of learning in Northland District confirm the decision to return to Northland District, but for some students was a factor that may have brought the possibility to front of mind, made them change their minds and decide to work in Northland District. Five concepts central to an understanding of rural practice12 (mentioned above) were reflected in the qualitative data, indicating that the Pūkawakawa Programme provided immersion in clinical practice that supported participants’ active learning about rural practice as students and prepared them for their later practice as junior doctors.

Regional and rural programmes are relatively expensive to deliver and this study provides evidence that the investment is justified. The learning experience, the unique design of the curriculum and associated support from clinicians were identified as important factors for encouraging students to work in regional and rural environments. However, discouraging factors can be beyond the control of students or universities, including separation from friends and families, geographical isolation and the availability of opportunities for partners to find work. Postgraduate education occurs at a crucial time in a doctor’s personal and professional life. For most specialties, this training is currently based in large urban centres, and trainees spend very little time in rural settings. Thus, mentor–trainee relationships, life partnerships, work opportunities for partners, purchase of homes, and stable childcare or schooling arrangements become established in urban centres30.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study are that we used multiple data sources in the form of questionnaires, interviews and discussion groups, and included doctors who had returned to work in Northland District, as well as those who chose not to return. In other words, this was not only a study about intentions but also about where graduates actually chose to work. The small sample size determined that only descriptive analysis was possible and that the findings may not generalisable to a wider population. Longer-term follow-up is required to determine whether these early postgraduate work choices eventuate in permanent work in regional or rural areas. The University of Auckland is part of the Australasian Medical Schools Outcome Database, which should enable longer-term follow-up, together with more detailed analyses of larger groups of students from diverse geographical settings and backgrounds31. Despite considerable effort to interview all graduates, a further limitation of the present study was the small number of Māori graduates interviewed. Approximately one-third of all students, to date, in the Pūkawakawa Programme have been Māori or Pacific and a similar proportion of Māori or Pacific graduates have been employed as doctors at the Northern District Health Board in their first postgraduate year. Consequently, the views expressed in this paper are largely those of European New Zealanders.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study has confirmed the value of the Pūkawakawa Programme as an important contributor to the regional and rural workforce, particularly in Northland District. It has affirmed the value of investing in and partnering with a DHB and primary health organisation, so that clinicians can provide a supportive regional and rural clinical learning environment. Although barriers to practising in regional and rural environments exist, this study provides further evidence that they can be successfully overcome to build regional and rural workforce capacity.