I would like to finish off my living here, at home. I have my grandkids; they are always coming and going from here. My late wife tried to put me in [a nursing home], but I got better and my son brought me back home because I did not like it there. Not for me! (client, age 67)

Introduction

This article describes an innovative, community-based palliative care (PC) program that was developed and implemented in rural Naotkamegwanning First Nation, Ontario. The aims are to describe the program and present an evaluation of its pilot implementation. The hope is that the information provided can guide other communities seeking to develop community-based PC programs.

A First Nations community, in this research, refers to a community populated by Indigenous people. In Canada, the term ‘Indigenous’, which is inclusive of Metis, Inuit, and First Nations people, is replacing the terms ‘Aboriginal’ and ‘First Nations’. Here, the term ‘First Nations’ is used because that is how the community self-identified during the research.

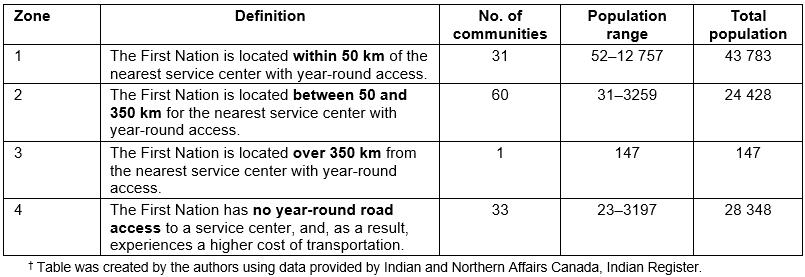

There are 617 First Nations communities in Canada, mostly located in rural and remote areas1. An interactive map illustrates the large geographic spread and populations of these communities2. One hundred and twenty-five of Canada’s First Nations communities are located in Ontario, with more than 950 000 community members (Table 1)1,2. Table 1 summarizes the rural and remote context of many of Ontario’s First Nations communities3. For example, almost half are between 50 and 350 km from a health services center, and 33 communities have no road access to health services (Table 1).

Table 1: Ontario First Nation communities by Geographic Zone (Remoteness): 20163†

Palliative and end-of-life care in rural and First Nations communities

PC is an approach to health care aimed at preventing and relieving suffering, and improving the quality of life for people living with life-limiting illness and their families4,5. End-of-life care (EOLC) is the final stage of PC; it begins when death is imminent, and typically involves enhanced services that are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week4. PC is of benefit for all people and their families living with life-limiting illness due to any diagnosis, including progressive chronic illnesses and frailty6,7. It is applicable across the illness trajectory, and can be provided concurrently with treatment8-10. Early access to PC contributes to increased satisfaction with EOLC experiences, and increased likelihood that people will die at home if that is their choice11,12. Initiatives are underway in Canada to integrate PC into home care and primary care programs6 to improve access where people live, including First Nations communities.

It is well documented that people who are dying in rural areas, including Indigenous people, have less access to PC13-18, and are less likely to die at home than their urban counterparts19. A review of the rural PC literature identified a lack of research-informed rural PC models, lack of research on the positive aspects of rural and remote contexts, and lack of strong theoretical underpinning20. The review concluded that emerging Canadian21 and Australian22 models that emphasize partnership and capacity development offer the most promise. In Canada, Kelley developed a community capacity development model that builds rural PC programs using local resources21,23. This model was adopted for use in First Nations communities24, and guided the research presented here.

Developing PC programs for Indigenous people is of international interest25. A recent review concluded there is a need for culturally specific models that are culturally appropriate, locally accessible and delivered in partnership with Aboriginal controlled health services18. The research presented here offers one such model that was developed through a partnership between a research team, community members and healthcare providers (HCPs) in Naotkamegwanning First Nation.

Need for palliative care in First Nations communities

In Canada, the need to develop PC programs in First Nations communities is urgent because the population is aging with a high burden of chronic and degenerative disease26,27. First Nations people want the opportunity to die at home in their communities25,28. However, First Nations communities lack the health services and other supportive resources to meet the home care needs of people with complex and high intensity care needs29. Thus, many First Nations people travel to urban areas for care, and die in institutional settings, separated from family, community and culture30-32.

First Nations Health Services Context: In Canada, the federal government is responsible for funding healthcare services in First Nations communities through the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB). Most communities administer the FNIHB funded health services locally, with services provided by internal HCPs who live and work in the community33. Hospital, physician and other external health services are under provincial jurisdiction, and delivered primarily by non-Indigenous HCPs who live and work outside of First Nations communities. The jurisdictional situation is such that a policy gap exists between federal and provincial jurisdictions, with both governments describing themselves as the payer of last resort34,35. This jurisdictional grey area is a barrier to the provision of health services, including home-based PC, in First Nations communities36. Moreover, no models exist on how the different levels of government can work together to fund and deliver PC services.

Home and community care services The FNIHB Home and Community Care Program (HCCP) was established in 1999 and provides basic home and community care services to First Nations communities37,38. The HCCP operates Monday to Friday, 8.30 am to 4.30 pm, and provides nine essential services: client assessment, managed care, home care nursing, home support personal care, in-home respite, linkages, medical equipment and supplies, capacity to manage program delivery, and record keeping and data collection37,38. Additional supportive services (including PC) can be offered through the HCCP if all essential services are being met, and funding is available within the approved budget. Thus, while FNIHB does not fund PC as a unique program, the services required to provide palliative home care are funded and in place (ie case management, nursing, personal care). However, in most communities the limited HCCP funding allows for only essential services.

The experience of Naotkamegwanning First Nation demonstrates how the local, federal and provincial HCPs and organizations came together to build local capacity, fund and deliver community-based PC in Naotkamegwanning.

PC Development in Naotkamegwanning First Nation

Community and health services context: Naotkamegwanning First Nation is in Northwestern Ontario (rural Canada) in the Treaty #3 Territory, and is designated Zone 2 remoteness (Table 1). The nearest urban center, Kenora (approx. 15 000 people), is 96 km north of the community. Naotkamegwanning has year-round road access; approximately 712 people live there. Naotkamegwanning has kept their Anishinaabe cultural practices and beliefs strong. Approximately 48% of the population speak Ojibway, and many people maintain a connection with the land.

The health services administered by Naotkamegwanning First Nation, including the community care program (CCP), are delivered by approximately 30 internal HCPs. The CCP has eight staff and consists of services integrated at the local level that are funded by both the federal (nursing, personal support and respite through HCC) and provincial government (home support and home maintenance through long term care). External (provincially funded) health services and resources are also available outside of the community. Prior to Wiisokotaatiwin, people with advanced chronic or terminal illness accessed health services and supports outside of the community. Even though these people would have preferred to die at home, all people living in Naotkamegwanning with progressive chronic or terminal illnesses (an expected death) died outside the community.

Developing the PC Program: The Wiisokotaatiwin Program was developed within the context of the Improving End-of-Life-Care in First Nations Communities (EOLFN) project, a 5-year participatory action research (PAR) project where researchers partnered with First Nations communities to develop local PC programs28,39. Over 5 years (2010–2015), Naotkamegwanning First Nation worked with the EOLFN research team to implement a community development process, and build PC capacity24,28. This included conducting a local needs assessment, and establishing a PC leadership team (composed of nine internal HCPs, Elders, and members of the Band council and administration) that guided program development.

The project resulted in a program model that addressed the gap for PC services in Naotkamegwanning0. The program was embedded in and influenced by local cultural protocols, values and beliefs. Within Naotkamegwanning, talking about death and dying is not culturally appropriate. The use of certain words had to be avoided, and there is no word for ‘palliative care’ in the Anishinaabe language. With direction from their Elders, the leadership team called their program Wiisokotaatiwin, which translates to ‘taking care of each other or supporting each other’. The vision was to have available for community members ‘coordinated comprehensive services for those wishing to return home to Journey, maintaining use of individual traditions and spiritual beliefs’0.

Program model

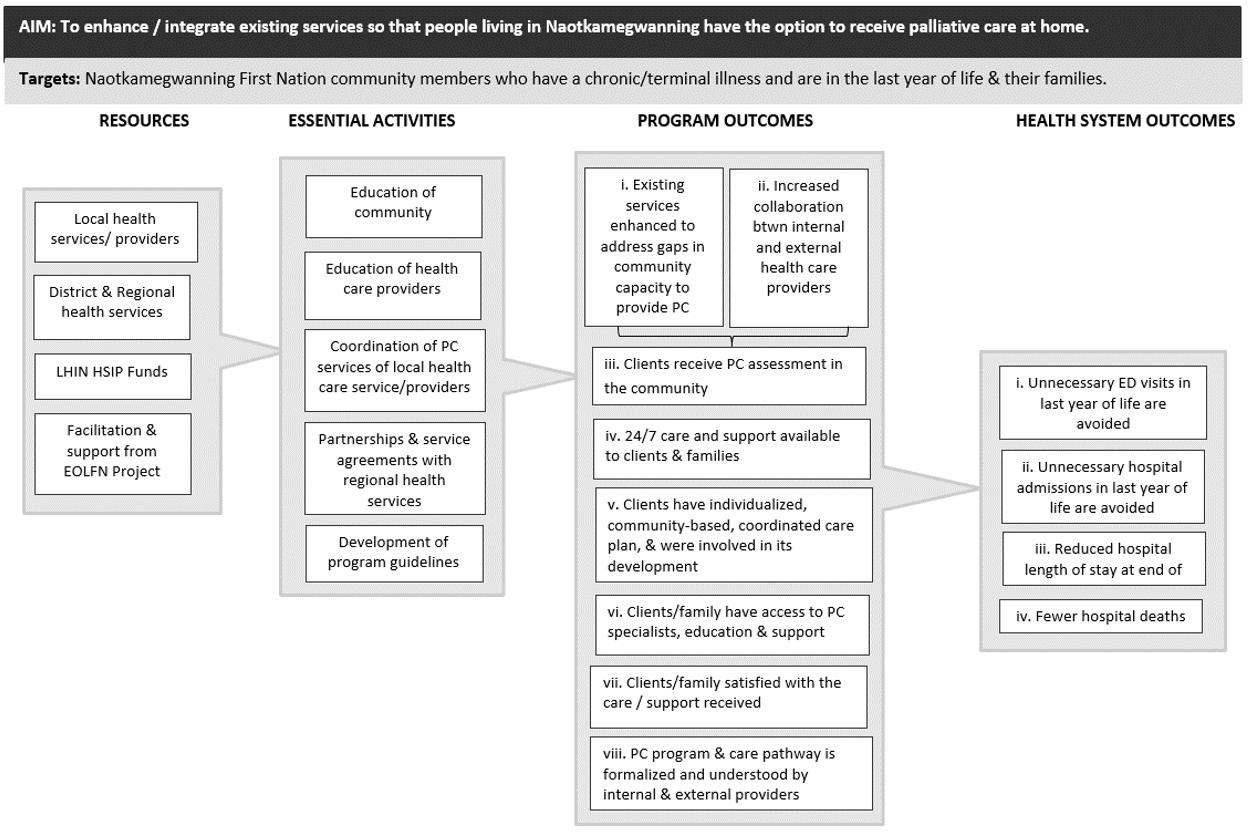

Through the enhancement and integration of existing services, Wiisokotaatiwin sought to provide people living in Naotkamegwanning the option to receive care at home by allowing for services and supports to be available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week in Naotkamegwanning. The required resources, essential activities and intended outcomes are summarized in Figure 1.

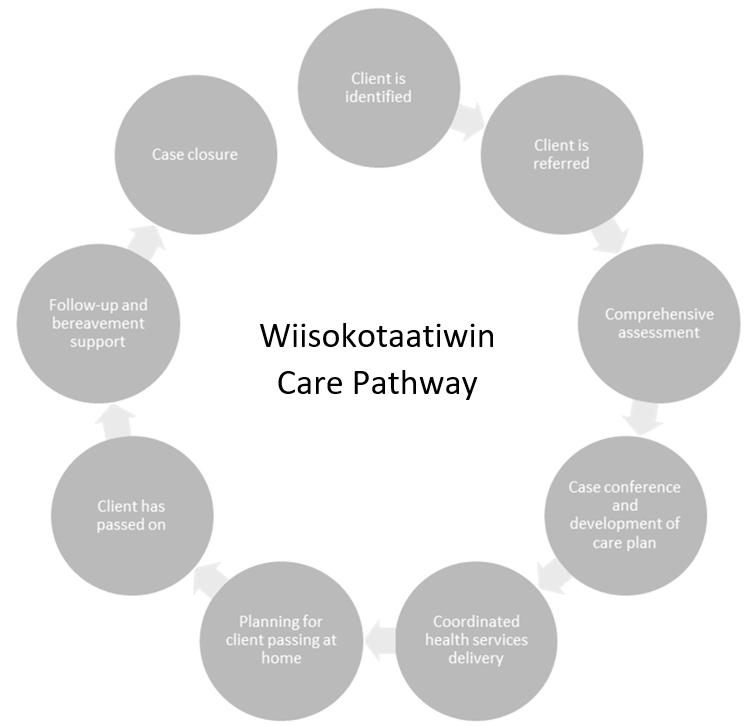

Figure 2 outlines the intended care for clients receiving PC, beginning with identification of eligible clients. Community members were eligible if they:

- could benefit from the services of the program

- wished to receive their care at home

- had an illness from which no recovery is expected

- had a Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) score of ≥60% with a prognosis of declining to 0% (death) within 1 year.

Prospective clients are informed about the program. With their consent, a referral is made to the program coordinator (who is also the coordinator of the CCP). Any HCP can make referrals; self and family referrals are also accepted. Upon receiving the referral, the coordinator visits the client to explain the program and conduct a comprehensive PC assessment. A case conference is then scheduled with the client and family to develop a PC plan; members of the circle of care are invited to the case conference as appropriate. Telemedicine is used when required to facilitate participation. An in-home PC chart is implemented.

During the case conference, a care plan is developed and shared with the circle of care. The plan includes goals of care, services to be provided, procurement and storage of medications, equipment procurement, and a checklist of services that can address all domains of care. The care plan is implemented through coordinated health service delivery. Nursing is provided by the CCP nurses (FNIHB) who already visit the community and know the clients and their families. The provincial home care organization provides professional health services other than nursing (eg physiotherapy, occupational therapy, social work). The services of the visiting nurse practitioner (NP) and physician are included as needed.

The coordinator is the client’s care manager and provides intensive case management. The CCP staff provide the required personal support, home making and respite care. Staff and family are instructed to call the coordinator with any questions regarding care, changes in health status, symptom crisis, and prior to taking client to the hospital. This support is always available, via a cell phone; family and staff are aware of who to contact when the coordinator is away from the community.

There is ongoing communication amongst the circle of care members. Reassessments are coordinated through the coordinator and CCP nurse, with required adjustments made to the care plan. If hospital transfer occurs, the coordinator contacts the hospital. The client is requested to bring the in-home chart for the reference of hospital staff. If the hospital visit is an emergency room visit, a follow-up note is placed in the in-home chart as to reason for visit, the treatment, and any further plan. For a hospital admission, the coordinator is involved in discharge planning.

EOLC discussions are initiated with the client/family at a PPS score of 30% (or earlier if appropriate). If the client is at home, the coordinator discusses with the client/family ‘what it means to stay home’ at the end of life, and what services the program can offer. A protocol for home passing is followed.

If the client is in hospital, the options for care and services in hospital and at home are explained. A client’s decision to be at home initiates a case conference and care plan revisions. After a client passes, program services continue as appropriate (eg bereavement visit from the coordinator), referrals are made to community services if additional support is required. When the file is closed, the coordinator arranges the return of equipment to agencies as required.

Figure 1: Wiisokotaatiwin Program logic model.

Figure 1: Wiisokotaatiwin Program logic model.

Figure 2: Wiisokotaatiwin care pathway. This figure Illustrates the expected care for clients on the Wiisokotaatiwin program.

Figure 2: Wiisokotaatiwin care pathway. This figure Illustrates the expected care for clients on the Wiisokotaatiwin program.

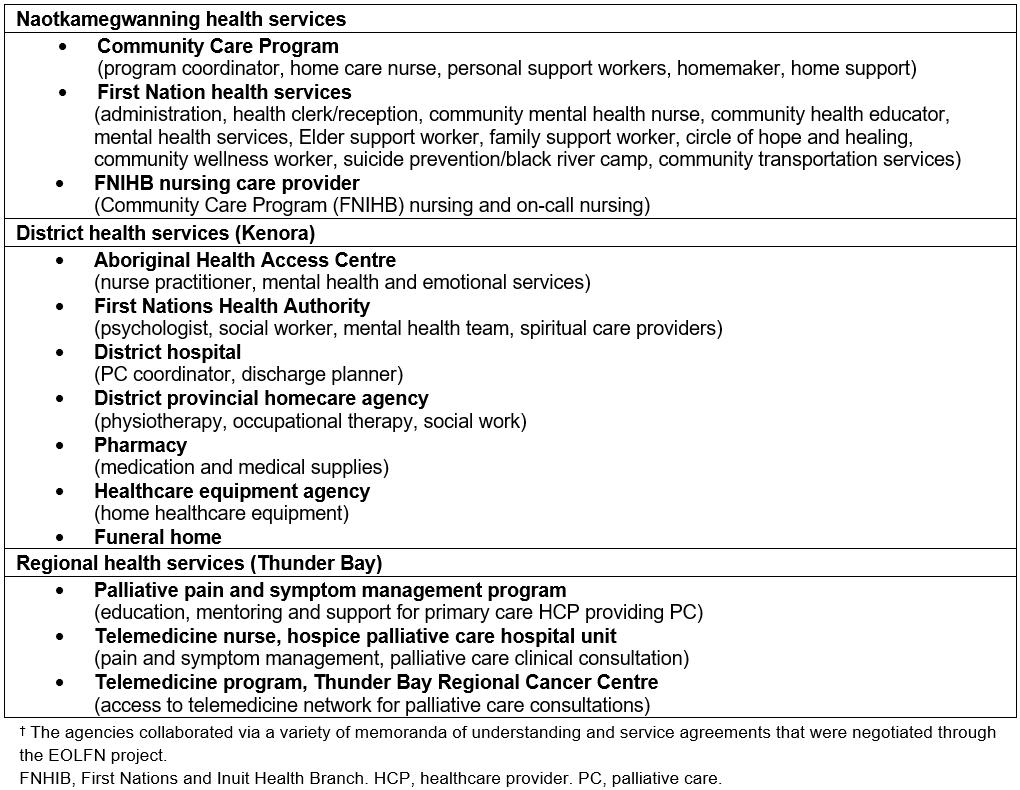

Implementing the pilot program

The community development resulted in the creation of the Wiisokotaatiwin Program model and care pathway. Partnerships and memoranda of understanding were also formed between internal and external services (Table 2). However, the community was unable to deliver the program due to a lack of service delivery funds in the CCP budget. Thus, the community applied to the Northwest Local Health Integrated Network (NW LHIN) for one-time funding to offer enhanced PC services and evaluate the program. (LHINs plan, integrate and fund provincial health care in Ontario.)

Naotkamegwanning received $60,000 over 10 months to pilot the program. Most of that funding (C$49 000) went to enhanced client services that were provided to six clients during the pilot (November 2014 – August 2015). These services included nursing, personal support and case management. The remainder supported staff education, equipment, and evaluation of the pilot. In addition, in-kind support (C$44 917) was provided by the EOLFN project, which consisted of paying for a part-time project facilitator, administrative assistant and project management.

Table 2: Internal and external health care providers, organizations, and services associated with the Wiisokotaatiwin care pathway†

Evaluating the program pilot

A process evaluation was conducted0. The evaluation questions and objectives were to:

- document program implementation:

- Who participated in the program (number and profile of clients)?

-

What services were provided to clients (by who and when)?

- assess progress toward outcomes:

-

What progress was made toward intended program and system level outcomes (Fig1)?

- assess the perceived value of the program:

- What is the perceived value of the program from the perspectives of HCPs providers, families, and clients?

-

Is the program model perceived to be transferrable to other First Nations communities?

Methods

To allow for a comprehensive understanding of the pilot’s implementation, outcomes and value, a mixed-method approach was adopted0. Quantitative methods were used to assess program implementation and outcomes, and identify trends in perceived program value. Qualitative methods were used to capture details regarding the experience of the program, and perceptions of its value.

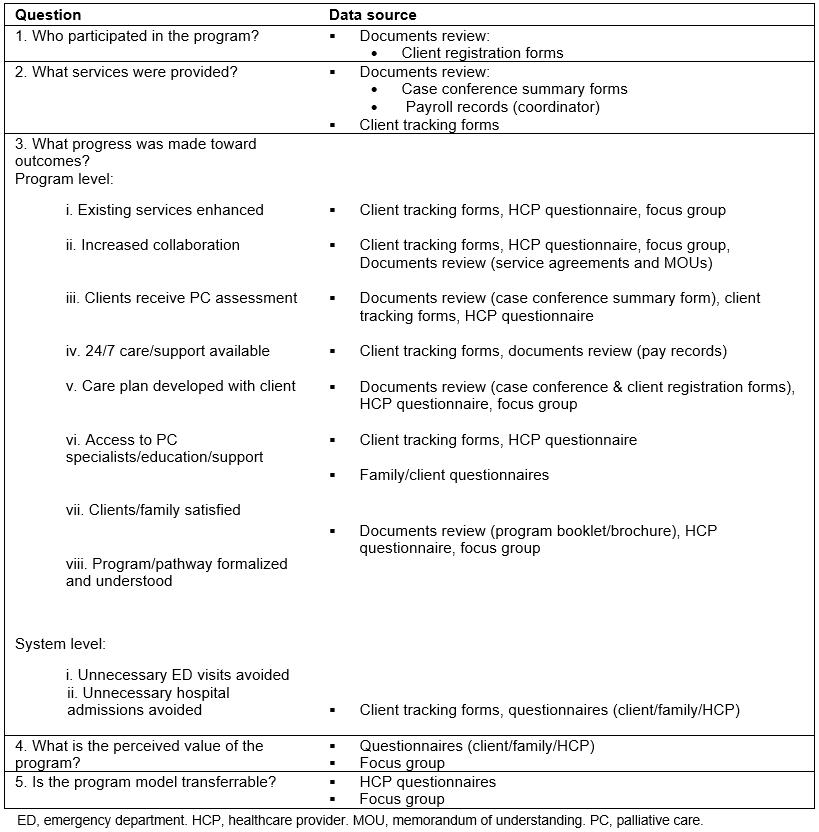

The data sources are described below and summarized (by evaluation question) in Table 3.

Table 3: Evaluation question/data source matrix

Data collection and analysis

Document review: Descriptive data were extracted from client registration forms, case conference summary forms, program booklet/brochure, purchasing and payroll records, and program invoices.

Client tracking forms: The coordinator completed one form per client at the end of every week. The forms were very detailed. Thus, to minimize data collection burden, the collection of service provision data was limited to a 4-month tracking period (May–August). Documentation included the services provided to each client (type, date, time, duration and provider), and hospital utilization information. The completed forms were sent to the research team for analysis. Microsoft Excel was used to organize the data and calculate descriptive statistics.

Questionnaires: Clients and family were invited to complete a short questionnaire at the end of the pilot. The questionnaire consisted of closed and open-ended questions that probed participants’ satisfaction with, and perceived value of the program (eight items). Seven completed questionnaires were returned to the research team for analysis (n=3 client; n=4 family). The quantitative data were entered into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v20 (SPSS; http://www.spss.com) for frequency analysis. The comments were organized by evaluation question (thematic analysis was not possible as very few comments were provided).

The internal and external HCPs involved in the pilot were also invited to complete an end-of-pilot questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of closed and open-ended questions (25 items) that probed the HCPs’ satisfaction with the pilot and their perceptions of the program’s value, the extent to which it met its objectives, and its transferability to other First Nations communities. A total of 22 completed questionnaires were returned: 8 internal HCPs (nurses, personal support workers, homemakers; an 89% response rate) and 14 external HCPs (a 74% response rate). The quantitative data were entered in SPSS for frequency analysis. The qualitative comments were analyzed using Thomas’s general inductive approach to identify themes in the text that were related to the evaluation questions0.

Focus group: An end-of-pilot focus group was held with members of the leadership team (n=5). Focus group questions probed the perceived the benefits and challenges of the pilot program. The focus group lasted approximately 1 hour and was audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis. Thomas’s inductive approach was used to analyze the focus group transcript to identify themes related to the evaluation questions0.

Ethics approval

This research followed Prince and Kelley’s Integrative Framework for Conducting Palliative Care Research with First Nations Communities, which consists of five components: community capacity development, cultural competence and safety, participatory action research, ethics and partnerships24. The overall PAR research project was approved by Lakehead University’s Research Ethics Board (REB #020 10-11) and the Chief and Council of Naotkamegwanning First Nation. All evaluation participants provided individual informed consent.

Results

Who participated in the program?

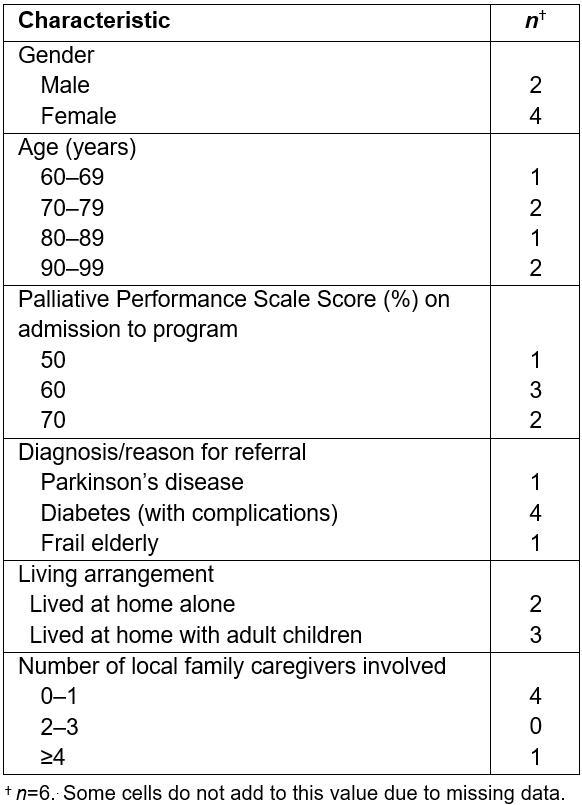

Seven community members were identified as eligible for the program. One member died early in the pilot, and did not receive services. Therefore, the evaluation focused on the services received by six clients. Four clients were on the program for the 10-month pilot; two registered toward the end of the pilot (May/June 2015). Table 4 details client demographic characteristics.

Table 4: Demographic characteristics of the Wiisokotaatiwin clients

What services were provided to clients (by who and when)?

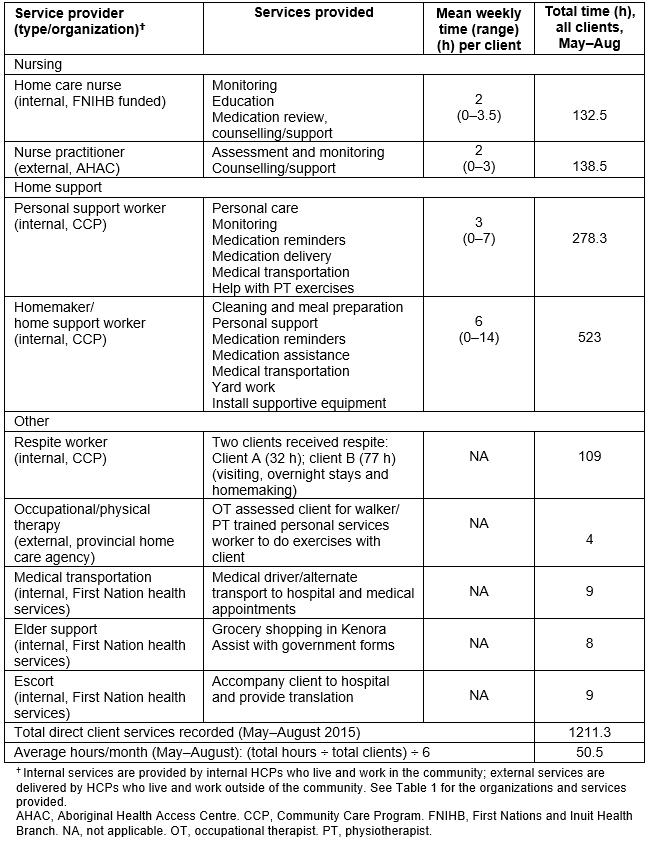

During the 4-month tracking period, clients received an average of 50.5 hours of direct client service per month (range=16–103 hours). Of the total direct service hours provided, most were for home support (homemaker, 43%; personal support, 23%; respite, 9%) and nursing (home care nurse, 11%; NP, 11%) services. Table 5 summarizes the service hours by type.

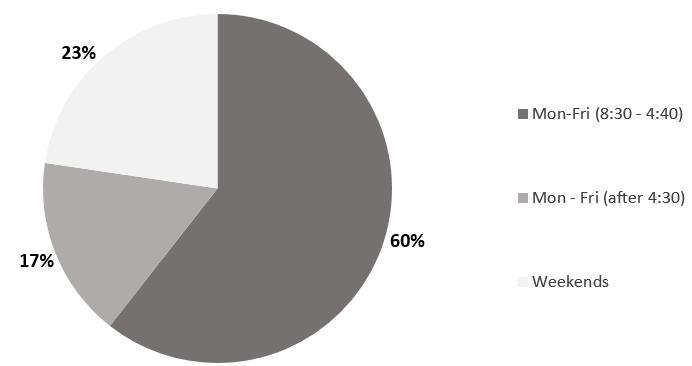

Forty percent of the home and community care services delivered during the 4-month tracking period were outside of the regular CCP hours (Fig3). Home support visits (personal support worker + home maker) accounted for most (81%) of the evening/weekend hours. Respite was also mostly provided on evenings and weekends.

During the 10-month pilot period, 812 hours were spent on intensive case management and program coordination. The tracking forms suggest that the coordinator was a key component of the program. Most of the coordinator’s time was spent on case management (PC assessment/reassessment, care coordination/scheduling appointments, referrals and linkages, obtaining supplies/equipment, and recordkeeping/data collection). Much of the coordinator’s time was also spent on communicating with clients/family and other members of the circle of care. The coordinator was also on-call via cell phone for families, clients and program staff.

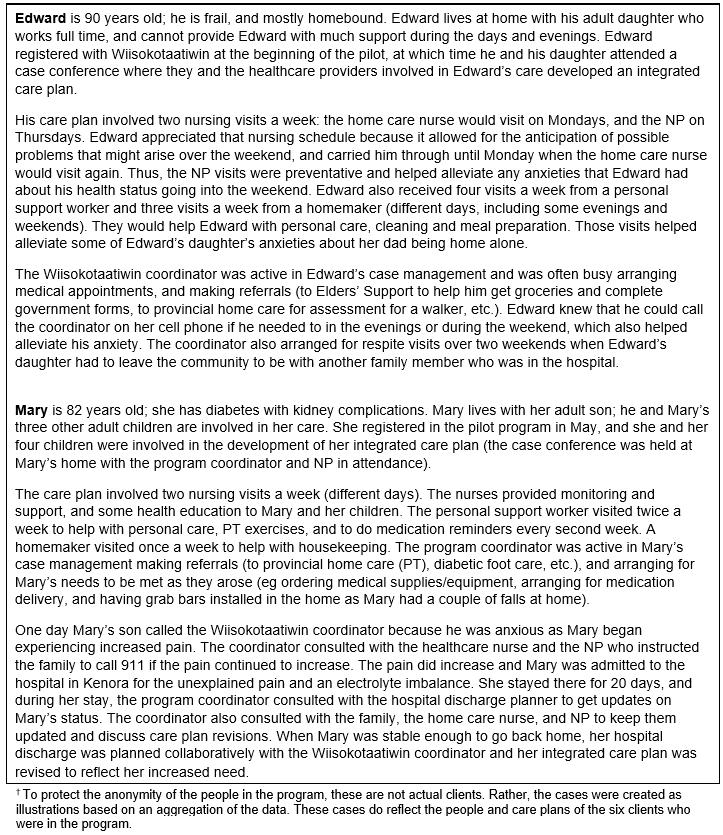

Composite case summaries were created to illustrate the demographic and service provision profiles presented above (Box 1).

Table 5: Direct client services provided to Wiisokotaatiwin clients (May–August 2015)

Figure 3: Proportion of services delivered to Wiisokotaatiwin clients by Naotkamegwanning Community Care Program by day and time (May–August 2015)

Figure 3: Proportion of services delivered to Wiisokotaatiwin clients by Naotkamegwanning Community Care Program by day and time (May–August 2015)

Box 1: Illustrative case scenarios† of the Wiisokotaatiwin services provided to clients during the pilot

What progress was made toward outcomes?

Program-level outcomes: The results for each intended outcome (Fig1) are presented separately.

i. Existing services enhanced Most of the pilot funding was spent on enhanced services for the six clients. Most of the services documented were an enhancement of the existing Naotkamegwanning health services (eg NP services, FNIHB nursing and program coordinator available on call, and additional FNIHB home care nursing and CCP home support hours), and provided to clients outside of the existing CCP hours (enhanced services; Table 5 and Fig3).

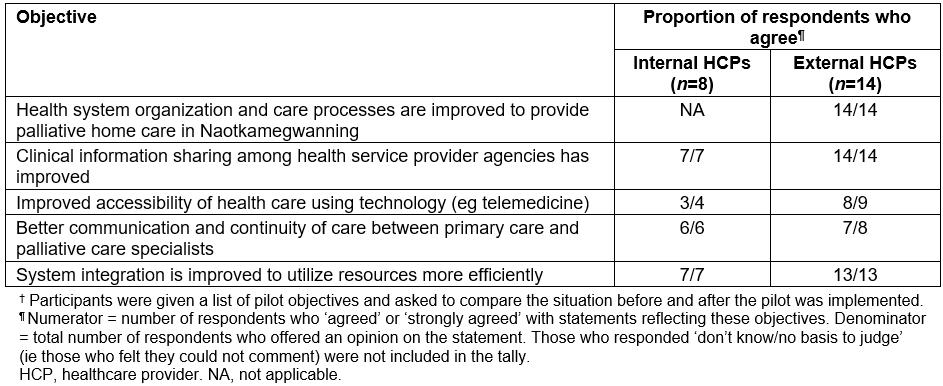

ii. Increased collaboration Formal partnerships and service agreements were in place (Table 2) and participants perceived the pilot to have resulted in increased collaboration among HCPs (Table 6).

During the tracking period, two (out of three) hospital discharges were planned collaboratively with the program coordinator. Baseline was that no discharges were planned collaboratively. The coordinator also consulted extensively with other external professionals in the circle of care for all six clients.

‘Increased collaboration and communication’ was also a theme that emerged in the focus group:

One of the major positive things that happened was creating those partnerships and starting that communication with our health care providers … Since the pilot, we’re starting to have those discussions and its change for the better.

iii. Clients receive PC assessment All six clients received a PC assessment in the community. A PC case conference was held for each client (in their home or at the Band administration office), and internal and external HCPs attended (sometimes virtually via telemedicine). An integrated care plan was developed for each client and the client/family were involved in its development.

iv. 24/7 care and support available Many of the CCP services provided to clients were delivered on evenings and weekends, outside of the regular CCP hours (Fig3). Moreover, the coordinator was on call via cell phone (funded by the pilot) for families, clients and program staff. Though not many after hour calls were received, the ones that were received needed to be dealt with immediately (eg locating and delivering client medication). When the coordinator was out of the community, the FNIHB nurses provided on-call coordination. No after-hours nursing visits were required because the coordinated and comprehensive process established by the program helped identify client needs and created a care plan that avoided crises. The program allowed the nurses to prepare the clients and families during regular business hours (FNIHB nursing supervisor, personal communication, 1 February 2016).

Table 6: Responses† to healthcare provider survey questions used to indicate increased collaboration

v. Clients have a care plan and were involved in its development An integrated care plan was developed for each client and the client/family were involved in its development.

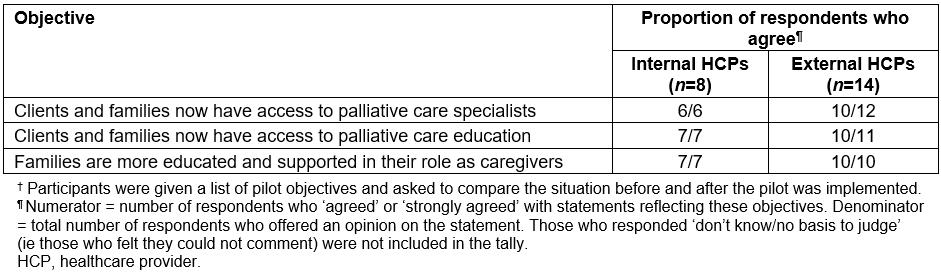

vi. Clients/families have access to specialists, education and support The coordinator often consulted with clients/families about their status and care plan, and had ongoing consultation with other members of the circle of care including PC specialists. The HCPs also felt that access to specialists, education and support was provided through the pilot (Table 7).

Table 7: Responses† to survey questions used to measure health care provider perceptions of access to palliative care specialists, education and support

vii. Clients/families are satisfied with the care/support received Clients and families were satisfied with the services provided through the program and felt their needs were being met:

- All family members (4/4) and most clients (2/3) surveyed indicated they were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with the services and supports received through the Wiisokotaatiwin Program.

- Most clients (2/3) and family members (3/4) felt that the program was meeting client’s needs.

- All family members felt that the supports received through the program met their needs.

viii. PC program and care pathway is formalized and understood by internal and external providers Program guidelines were formalized into a program booklet and brochure0. The program description was sent to all agencies involved in the pilot. Education was done at the hospital for physicians and nurses.

System-level outcomes: The short timeframe of the pilot and lack of access to hospital data precluded the evaluation of longer-term system level outcomes (Fig1). However, the pilot data indicate some progress toward these outcomes. During the tracking period, the coordinator reported that the services provided by the program prevented an emergency department visit for four clients (eg locating and delivering medications), and reduced the length of hospital stay for one client (eg catheter care could be provided at client’s home). One family member also commented:

We as family panic about every little thing. It was much easier when we knew [NP] was going to be near and the on-call nursing was available.

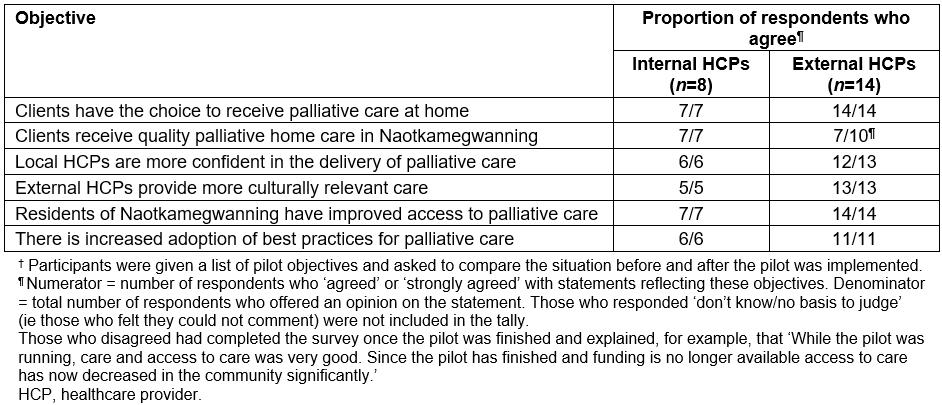

What is the perceived value of the program?

Questionnaire data indicated that the HCPs thought the program was valuable (Table 8).

The survey findings also indicated that HCPs were satisfied with the program, and felt it was a promising practice that should be continued in the community:

- All HCPs surveyed (22/22) indicated they were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ working within the new model of care of the Wiisokotaatiwin Program.

- When asked '‘In your opinion, is this new model of service delivery a promising practice to be continued in Naotkamegwanning?’, 11/14 external providers, and 7/8 and internal providers answered 'Yes' (the remainder said they didn’t know – none answered 'No').

One provider explained:

Our very sick patients [who] don't like hospitals would want this program so they can stay home with family and that's a very needed thing. (internal HCP)

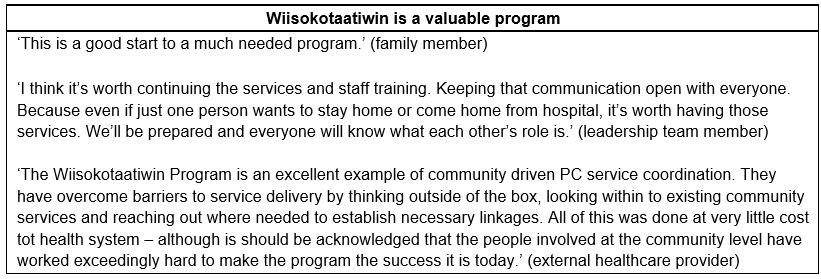

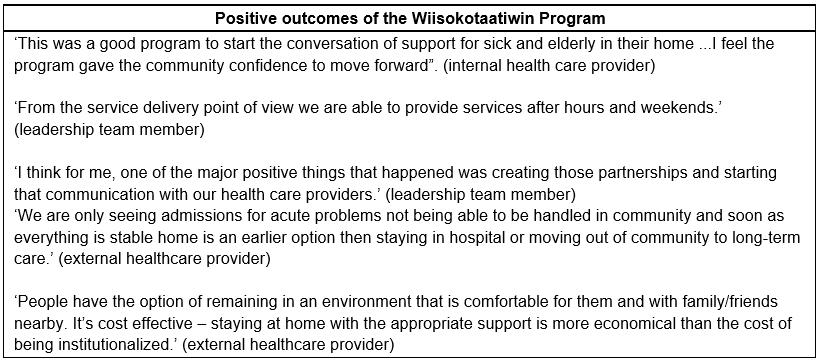

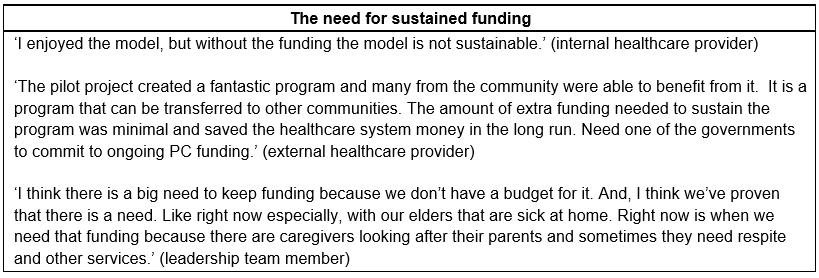

In addition, analysis of the focus group and open-ended survey data indicated that stakeholders perceive Wiisokotaatiwin to be a valuable program, and that it made progress toward its intended outcomes during the pilot (boxes 2,3). However, there was concern that without continued funding for the additional service delivery, the program was not sustainable (Box 4).

Table 8: Responses† to survey questions used to indicate healthcare provider perceptions of program value

Box 2: Illustrative quotes for the qualitative theme ‘Wiisokotaatiwin is a valuable program’.

Box 3: Illustrative quotes for the qualitative theme ‘positive outcomes of the program’.

Box 4. Illustrative quotes for the qualitative theme ‘the need for sustained funding’.

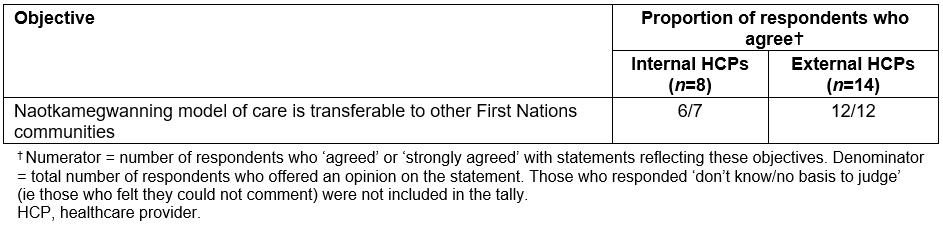

Is the Wiisokotaatiwin Program model perceived to be transferrable to other First Nations communities?

The HCPs involved in the project thought that the program model was transferrable to other First Nations communities (Table 9).

Some providers explained:

Although every First Nation community is different, this model could definitely be adopted and adapted by other communities looking to plan and implement PC services. (external HCP)

Health care services need to be better integrated. This model provides an example that can be transferred to other contexts and communities. (external HCP)

Table 9: Healthcare provider perceptions on the transferability of the Wiisokotaatiwin Program model

Discussion

This article described an innovative, community-based PC program that was developed and implemented in Naotkamegwanning First Nation. The paradigm adopted in this research focused on strengths (First Nations communities have existing capacity that can be developed to provide formal PC) rather than deficits (First Nations communities lack the resources required to provide local PC programs). Through a community development process using Kelley’s model21,24, HCPs and programs from the provincially and federally funded healthcare systems came together to support community members from Naotkamegwanning28. A program model and care pathway was developed which overcame jurisdictional barriers. A unique feature of the program model is the enhanced collaboration between federally and provincially funded health services.

All essential activities and resources (Fig1) were in place, and were essential to implement the program and achieve its outcomes. In terms of resources, there were sufficient infrastructure and health services to allow development of the local PC program28,28. Specifically, there were local PC service providers and district and regional health services who were available and motivated to assist (Table 2). This allowed for the adoption of a service enhancement and integration model. Moreover, the facilitation and support from the EOLFN research team supported the program development and implementation, and the LHIN pilot funding was instrumental in implementing the program0.

The evaluation documented program implementation and assessed program value and progress toward outcomes. The findings demonstrate the program was implemented as intended, and that there was a need for the program, with six clients on the 10-month pilot. Though the pilot period was short, the findings also indicate achievement of and progress toward outcomes (Fig1). At the program level, all eight intended outcomes were achieved. Progress was being made toward outcomes at the system level (ie tracking data suggest that unnecessary emergency department visits and hospital admission were avoided). The findings also suggest that clients/families and HCPs were satisfied with the program, perceived it to be meeting its objectives, and thought it was worthwhile. The program model was also perceived to be transferrable to other First Nations communities, further indicating its value.

Overall, the findings suggest that the main goal of the program, to enhance and integrate existing services so that people have the option to receive PC at home, was met. Though not a costing study, the evaluation data suggest that keeping First Nations community members at home is not very expensive. The C$60 000 pilot funding allowed for the enhancement of existing services to address gaps in community capacity to provide PC. However, due to lack of sustained service delivery funds, enhanced services were unable to be provided once the pilot ended.

A few limitations of the evaluation are of note. There is the potential for human error in the completion of the client tracking forms because they were being completed by very busy service providers who already documented service for other purposes. To minimize error, the project resource person assisted with completing the tracking sheets. Future evaluations should streamline this data collection.

This research was based in one First Nations community in Ontario. It is recognized that social determinants of health and community capacity vary among First Nations communities. For example, a lack of housing infrastructure has resulted in overcrowding in homes in many First Nations communities. Because social determinants of health impact whether community members can be cared for at home at the end of life, the overall community capacity must be assessed prior to doing this type of community development work.

It was difficult to assess the system-level outcomes of the pilot for several reasons. The evaluation team was unable to access hospital utilization data for the Wiisokotaatiwin clients. While the tracking sheets documented hospital utilization, that was only for the 4-month sample period. Relatedly, a 10-month pilot period was too short to evaluate system outcomes. The eligibility criteria required a client to be in the last year of life, but the pilot period was less than 1 year (only one client died during the pilot). Finally, the pilot had a small number of clients (n=6). Despite these limitations, the details reported here have important implications for PC development in First Nations communities, and can guide planning and decisionmaking.

Conclusions

The experience of Naotkamegwanning demonstrates how local, federal and provincial HCPs and organizations can collaborate to overcome jurisdictional barriers to fund and deliver community-based PC. This article illustrates that Naotkamegwanning had the motivation and capacity to care for their very sick community members at home. The LHIN funding provided the needed opportunity, as did support for the community development process from the EOLFN research team. As a case study, this project suggests that other First Nations communities with similar motivation, capacity and opportunity could implement a local PC program, tailoring their program to their unique community needs, local resources and regional context. The program model and evaluation presented here will be helpful to policymakers, programmers and other communities looking to develop local PC programs. As an approach to community capacity development in PC, this study provides a model that has relevance to assist Indigenous communities internationally.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Naotkamegwanning Leadership Team members and the program partners who made the Wiisokotaatiwin Program possible. We acknowledge that the Naotkamegwanning participants have ownership of the knowledge created, and thank them for allowing us to share it internationally.