Introduction

In South Africa, national health policy mandates a strong district healthcare system1, recognises the human resources for health requirements to graduate an increasing number of medical students2 and acknowledges that graduates’ training also needs to prepare them for practice in contexts of primary and secondary care. These create an imperative for medical student training to include exposure to a distributed clinical platform. Medical schools in the country are responding by extending their clinical training platform to include district hospitals and their surrounding clinics.

Many of these new sites are geographically distant from the education institutions they serve. While students may have spent time at these sites for elective components of their curriculum, they have not traditionally been used for core components of it. Typically, high level agreements govern the relationship between the education institution and the provincial Department of Health3, but individual clinicians at distributed sites do not necessarily have any formal link with the medical school. In addition, the selection of distributed training sites is often opportunistic, based on the willingness of the district and facility managers to accept students at the site. Clinicians working at these sites seldom view themselves as academics; they may never have had the intention to be anything other than practising clinicians and would have had few opportunities to include teaching in their professional activities. A site is not necessarily selected because the clinician is deemed to be a good teacher.

Billett’s research on workplace learning4, the domain in which clinical training falls, suggests that appropriate selection and preparation of the person guiding the learning (in this case the clinician teacher) is fundamental in enabling them to offer affordances to the student so that quality learning occurs. Research conducted previously by the research team working on this article, with clinical specialists working and teaching in the contained and well supported rural clinical school of the authors’ faculty, described their journey to becoming clinician teachers5. It began with concerns around incorporating teaching into their clinical practice, but moved through initial uncertainty about their role to an emerging identity as a clinical teacher and finally embracing responsibility for teaching future colleagues. The context of that research was a new educational initiative (the first in the country) designed to address the health workforce needs of the country, and located only 100 km from the medical school, where there was strong and visible support (including educational support to the clinicians) enabling this journey. Wanting to take that research further, the authors chose to explore the clinical teaching experience of clinicians who were even more distant and not part of the rural clinical school.

All medical faculties have the responsibility to graduate competent health professionals into professional practice and therefore an obligation to assure the quality and effectiveness of their students’ clinical teaching. As a result, there is a growing focus on how clinical teachers can be supported in this task. Prior to this empirical work, it was thought that to strengthen clinical teaching on the expanding training platform, it would be necessary to take traditional forms of faculty development activities (workshops and short courses held in the medical school covering aspects of clinical teaching and assessment) to the workplaces of these newly involved clinicians. Frenk et al’s6 challenge, that there is a need to support the health professions education subsystem through faculty development, was recognised. There was acknowledgement of the incongruence of providing opportunities to strengthen clinical teaching in formal workshops at the central medical school (away from the context of the clinical workplace), leaving the clinician with the challenge of implementation when they return to the decentralised clinical environment. Steinert’s 2012 call for ‘a framework for faculty development, with a particular focus on experiential and work-based learning, role modelling and mentorship’ was considered7. However, little was found on how these constructs should be translated into developmental opportunities that will enable clinicians to deliver effective clinical teaching, and particularly how these could be delivered for clinicians at distant sites. This led to a consideration of what would be needed to inform creative responses to the very real implementation issues, which so often impact on the translation to practice of more traditional forms of faculty development.

Most medical education literature (including that on clinical teaching) originates from North America, Western Europe and Australia8,9, from higher education settings that are well resourced and health systems with high doctor–patient ratios. It is unlikely that the underlying principles of effective clinical teaching10-12 should be markedly different in resource-constrained settings. However, it can be argued that there is a need to consider how this can best be supported and delivered in the workplace of small hospitals that are geographically distant from the education institution, without expertise of experienced faculty, and where there are limited human, financial and technological resources, such as is the case in South Africa.

The research reported here sought to develop an understanding of how clinicians working at distant resource-constrained and emerging training sites view their early experiences of having been delegated the task of clinical teaching. This was with a view to inform the development of initiatives that could strengthen their role as teachers.

Methods

As an understanding of the views and subjective experiences of clinicians taking on the role of clinical teaching was desired, qualitative research using an interpretive approach was chosen13. Clinicians were studied in their natural settings, with the aim of making sense of the phenomenon of the emerging clinical teacher by interpreting the descriptions of their experience.

At the time that this research was conducted all the authors had some responsibilities for contributing to the quality of clinical teaching provided by the faculty, although none were clinical teachers. JB was working in educational capacity development, MdV was responsible for the quality assurance of undergraduate education and SvS was contributing to the professionalisation of health professions education. JB and MdV are family physicians familiar with both this research context and some of the participants.

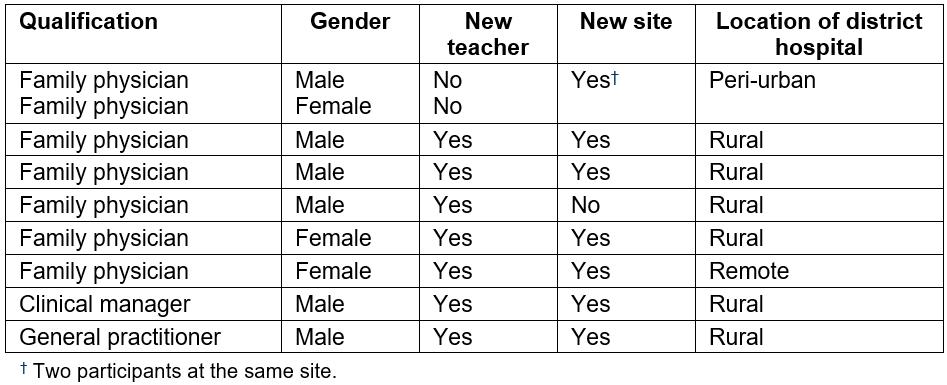

The setting for this research was district hospitals in South Africa where medical students spend five weeks doing a clinical rotation in rural health care. Sites were between 65 km and 1200 km from the medical school campus and its traditional tertiary academic teaching hospital. Of particular interest were clinicians who had recently taken on the role of clinical teacher, or clinicians who were working at sites newly used for clinical teaching. It was assumed that new sites would not necessarily have an established culture, history of or expertise in student teaching, or a developed community of pedagogic practice. Although the clinicians are not considered staff of the university, there is an expectation from both the medical school and the Department of Health that clinicians be involved in clinical training3. In this case, the authors were exploring their responsibilities with regards to clinical supervision. They also facilitate students’ quality improvement projects and home visits. Within the distributed training platform at the time, there were nine clinicians (seven of whom were family physicians) at eight different training sites who fulfilled the above criteria. All were approached and invited to participate in an interview and all consented to do so. Table 1 shows the demographic details for the participants.

While the majority of family physicians had completed a module in teaching and learning during their specialist training, none of the participants had attended any of the faculty development opportunities for strengthening their clinical teaching abilities offered at the medical school.

In-depth interviews were conducted by the principal researcher between July and December 2015. Duration of the interviews was 36–95 min, with an average of 60 min. All but two interviews were conducted at the participant’s place of work; one was in the village coffee shop and the other at the participant’s home.

As it was the authors’ intention to generate a narrative account of the clinicians’ experiences as educators, the interviews were unstructured, commencing with ‘Can you tell me what it is like for you as a clinical teacher?’ Further probing was done where necessary, led by the findings of the authors’ previous research5, in order to explore the participants' clinical teaching practice and how it could be strengthened.

Interviews were audio-recorded and then anonymised during the process of verbatim transcription. They were coded inductively by JB, using Atlas ti v6 (https://atlasti.com), looking for underlying meanings, which were then grouped into categories. The codebook and categories were discussed with, adapted and agreed to by all the researchers.

There is a challenge to develop not only code saturation but also meaning saturation14. This meant that although the study population was limited, the authors were sensitive to the need to obtain a deep understanding of the data from the nine interviews. This was done through an iterative process of reading and coding, reflecting on previous research with clinician teachers, and utilising an understanding of both the participants and the context.

Table 1: Demographic details for study participants

Ethics approval

Approval for this research was obtained from the Stellenbosch University Health Research Ethics Committee (N14/08/097) and the Western Cape Department of Health.

Results

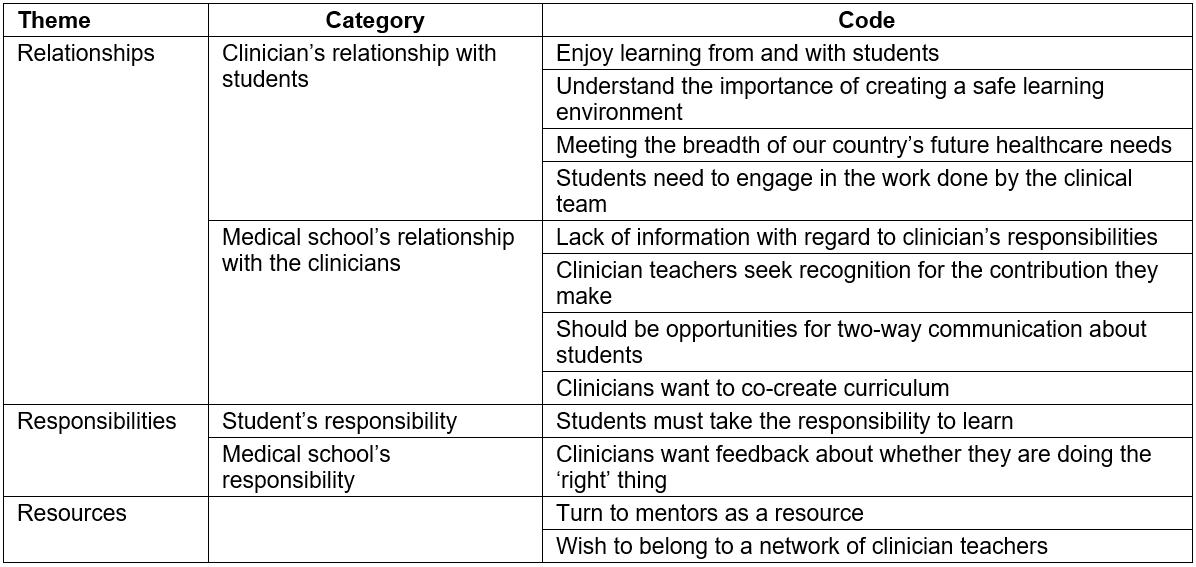

Three themes emerged during the analysis: relationships, responsibilities and resources. Table 2 presents the codes, grouped into categories and themes. The dominant theme concerned the relationships that the clinicians have with students, and those that they miss having with the medical school. The respondents recognised the student’s responsibility in learning, embraced their own responsibility for teaching and called on the medical school to fulfil its responsibility to support them in this delegated task. The resource that the clinicians would turn to most often was trusted colleagues.

Table 2: Themes, categories and codes from the interviews

The following illustrative quotes from clinicians (C) capture how meaning was made of the data.

Relationships

Clinicians’ relationships with students: Enjoy learning from and with students Clinicians enjoyed the intellectual exercise of having students with them, expressing enjoyment at being challenged and having the opportunity to update their knowledge (either with information from students, or from being provoked into checking on latest evidence by a student’s question). By creating a relationship in which patients could be discussed together, the diversity of knowledge, experience and interests brought a richness to conversations around patient management and problem-solving.

… it’s valuing people’s differences and people’s different perspectives, and realising that there is something you can learn from a third year student, there is something you can learn out of a situation. Yes, it’s quite exciting to be able to grow together and work as a team. (C5)

Understand the importance of creating a safe learning environment All the clinicians spoke of the importance of their relationship with the student. They recognised that it was important to create a relationship where the student found them approachable, enabling them to trust that they would be ‘safe’ both to ask questions of the clinicians and to contribute to decision-making. The clinicians related this idea of safety to the student feeling able to be vulnerable enough to expose the gaps in their knowledge and skills.

I think maybe the teacher sets the framework in which that person can experiment and learn safely. (C6)

Meeting the breadth of our country’s future healthcare needs Clinicians were also aware of their role in contributing to the type of medical practitioner that they would like to see in the workforce. They positioned their relationship as an investment in the country’s future health care by exposing students to skills appropriate for care outside of tertiary hospitals, and offering them an experience that would develop a respect for the healthcare service provided by these clinicians in decentralised sites.

… ultimately I want my hospital staff, ultimately I want staff, empathic doctors who have a good sense of self-control, a good sense of self, are resilient, wise practitioners. I think that’s what I am looking for, wisdom and experience and introspection … I’m trying to do that, but it’s also, from an idealistic point of view, I think that’s how a good person should be, so I’m trying to make everybody into that person. (C6)

Doctors need to be trained in the district facilities. That is where doctors need to be trained. ... They need to see TB, they need to see HIV, they need to see COPD, they need to see asthma attacks, they need to see uncontrolled diabetes. That is the thing that they need to see, and if I think, if I only could learn those conditions and I learnt them well, I would have been a much better doctor. … … they will have respect for that doctor sitting in the periphery. (C2)

Students need to engage in the work done by the clinical team The respondents felt that, in order for teaching to happen, the student must work with the clinical team. This reciprocal relationship involved giving the student clinical responsibilities and acknowledging the student’s contribution to the team’s diagnostic reasoning, problem-solving and learning with regards to patient care.

Often I am doing things and I think this would be nice for a student to see, but they are nowhere to be find [sic], and I’m not going to now go and call a student or whatever. They must just be around and absorb. (C5)

Medical school’s relationship with the clinicians: Lack of information with regard to clinicians’ responsibilities There was minimal or no orientation of the clinicians, which left them in doubt about what was expected from students and what the intended learning outcomes were.

… just to know what the vision for the university is, for this institution, for the students, I’d love to get on par, just to make sure that I’m still on the right track. (C1)

Ideally I would want to know exactly what is the expectation … and to have clear guidance on it. I think it’s a problem, because I don't think the departmental guys all have a clear understanding of what that is, you know. I don’t think everybody is on the same page as to what the required standard is … we need to understand what they need to know. (C7)

Clinician teachers seek recognition for the contribution they make The respondents thought that the medical school was not really recognising the magnitude of what it was asking of them and was not offering them support to do the job.

I feel like the university needs to get off – I almost want to say – get off their throne, and come here and say we need to train medical students, how are we going to make this happen that we support you so that you can still render your service, but that you can train our doctors because we need you to train our doctors. We need you to train our doctors. (C2)

I didn't feel any support at all from the university. I did get a lot of jobs from the university, but I felt no support. (C6)

Should be opportunities for two-way communication about students Clinicians at more geographically dispersed sites felt they did not have channels of communication that could be used for receiving information regarding students arriving for a rotation, or for expressing concerns about students currently in a rotation with them.

Actually, one of the things, and it’s probably bitterly unfair to say this, but to know what to expect when your student walks through the door. It’s probably unfair in a lot of senses, but if you know the student coming is borderline, it changes your expectation. (C7)

… the channels for feedback should be more obvious, and more laid down so that … feedback, sometimes subjective, sometimes objective, but feedback about the students to the university, I think is also important. (C5)

Clinicians want to co-create curriculum In terms of relevant curriculum content, clinicians expressed that, as the training platform had expanded into different contexts with different case mixes, the consequences should be incorporated into re-aligning the curriculum.

… being able to sit down and be part of the planning discussions … to also be seen as a valuable member of that team, and to be able to bring some of my varied experiences to that, and have them open for that. (C5)

Responsibilities

Students must take the responsibility to learn: Clinicians seemed to feel that creating an environment of trust and approachability would allow them to put responsibility for learning in the student’s court. They expressed that students needed to take responsibility for their own learning in the clinical environment. This was often expressed as the student needing to be able to come forward to ask questions. There was a sense that answering questions posed by the student was a way to meet the student’s needs without needing to ‘teach’ in the context of their own busy patient schedule.

The other thing I tell them when they arrive here, I say listen here, see me as your friend, I want to teach you something, what I want, but it depends on yourself. Not on me. (C3)

… putting the ball in their court, that they are going to learn as much as they are willing to learn, and the more they ask questions, the more people are going to think they are keen to learn, and the more people will actually remember to call them for specific clinical scenarios … there is a measure of responsibility that comes from the student’s side as well … so there has got to be a drivenness [sic] in the students as well. (C5)

Clinicians want feedback about whether they are doing the 'right’ thing: Clinicians wanted to know that they were doing what was expected of them, but had not been given any information about whether they were doing what was required concerning teaching.

I would like to know if the Faculty is happy with how I’m doing it. Not with me, how I’m handling it. That’s all that I want to know. (C3)

We never get that feedback [how the students do in their exams], and we would really appreciate it, because it would help. (C8b)

… give me a more secure sense of actually, are we on the right track, at least with these pre-graduate students … and is what I’m doing still the right thing. (C1)

This uncertainty seemed to underlie a willingness to have their clinical teaching evaluated by their students. While clinicians referred to how challenging it might be to receive this sort of evaluation, there was a strong desire to improve their teaching practice by being informed of which areas required attention.

I prefer to think of myself as somebody that can take criticism and I actually prefer to know if I’m doing something that is either wasting somebody’s time or that is not correct. So even though it might be a bitter pill to swallow I’d prefer to rather know that than to continue on with my own stupidity. (C4)

Resources for clinicians

Turn to mentors as a resource: In general the participants would turn to people they recognise as mentors to discuss issues around teaching or in responding to student evaluations.

… otherwise if you are aiming towards teaching, teaching, or helping me to learn how to think, I think I’m more like a questions based person, so if I have a question, I would like to have somebody that I can go to. Usually I will have another question and another and another, so it’s nice to be able to have somebody that actually has time sometimes to speak with you for a sort of longer period of time, and that will ask you your blind spot questions. There is so much direct learning, but obviously you are going to have those blind spots. So somebody else kind of pinches you in your blind spots. (C6)

I find that mentorship is not something that we stress enough, and we almost kind of are afraid of that. I mean, even if I tell XXX you are my mentor, he will kind of, not really, you know. For me it’s extremely important. He actually needs to understand how important it is for me, and actually take the responsibility of that. (C2)

I would definitely discuss it with people that are more knowledgeable, people that are also in the teaching business, especially medical teaching, like you, with XXX or someone. I would ask them ‘listen, is there no possible way that I can actually improve my own skill?’ (C1)

Wish to belong to a network of clinician teachers: The participants expressed the need to belong to a group where issues related to clinical teaching could be discussed and where they could strengthen their teaching skills.

… that kind of more formal networking system and almost debriefing system and community, like sense of community and team that comes out of those kinds of contact sessions together, is also very valuable, and it definitely did have an impact on the teaching we received as well. So I think it’s a very valuable model. (C5)

These findings show that these clinicians intuitively grasp the social aspects of learning; they are keen to contribute to students’ learning, particularly if students take an active role in participating in the clinical work; and they want to do ‘the right thing’ as clinical teachers. The participants embrace having students at their facilities, seeing this as a way to keep themselves up to date with clinical advances, but also as an investment in the future, making a contribution to teaching the sort of graduates that they would like to employ or work alongside in the future (relationships). They strive to provide a good ‘experience’ for the students through which the students will respect the service provided at the facility and may consider rural practice as a career option. However, they also indicate that they would like a stronger relationship with the medical school, expressed as first being acknowledged for their contribution and creating opportunities for them to become more effective clinical teachers, and second as a desire to both contribute to curriculum re-alignment and have a voice in student evaluation (roles and responsibilities). In addition, when needing advice or mentorship concerning clinical teaching, they would turn to trusted clinical colleagues and mentors (resources).

Discussion

The findings from this research suggest a need to explore creative responses to issues not traditionally dealt with in faculty development initiatives: relationships, responsibilities and resources. We argue that these three Rs should be foundational considerations when faculty developers consider how best to assist emerging clinical teachers. In her commentary on McLean et al’s Association for Medical Education in Europe guide on faculty development15, Lieff calls for us to consider the critical issues of context and design when implementing faculty development initiatives16. The authors have explored a context that is assuming a more prominent position in medical education where emerging clinical training environments are geographically distant from the central medical school. In 2002, Worley proposed a model17 of relationships that were key to enabling high quality, community based education for medical students. The research presented here seems to take his proposal that ‘relationships do matter’ further by finding that relationships also matter for the clinician teachers in community based education. In this case, the desired relationships extend beyond students, to their clinical peer support network and the university faculty. Findings from a self-administered survey asking rural general practice preceptors in Tasmania about their educational needs, were very similar to the present study’s findings, in particular the desire for contact and communication with university staff and to have a role in the curriculum18.

Traditional faculty development activities that are designed to ‘teach’ relevant pedagogical knowledge and skills are still necessary, but they may no longer be sufficient for clinicians in these contexts. Such practices may need to be extended by specifically designing for a process of engaging existing networks of clinical practice so that pedagogical expertise can be vested within a group that already access each other’s expertise for clinical support. While this is not necessarily viewed within the traditional remit of faculty development, it can be seen as an organisational re-alignment that talks to Steinert’s call for creation of communities of practice19 and Lieff’s reminder that as faculty development initiatives are organisational development initiatives, we are required to create shared ownership in order to be successful16.

Senge’s work on learning organisations20, Wenger’s work on communities of practice21, Eib and Miller’s article on faculty development as community building22, Sherbino et al’s depiction of the evolution of a community of practice amongst a group of clinician-educators23, van Schalkwyk et al’s article describing the need to create spaces for academics to flourish as teachers24, and others, have relevance in this context. They all advise that effective design of faculty development initiatives needs to include deliberate attention to development for those who participate, and opportunities for membership of communities of practice with ongoing relationships where participants can continue to engage with people they know and trust. When dealing with clinicians who are geographically dispersed, this becomes of even greater importance as they have limited access to medical school resources. The participants in this research did not see faculty developers, or teaching modules, as where they would turn to if they needed advice. They identified their most likely resource as their own social learning environment. This may suggest that faculty developers should consider designing new methods that include entering and working with the social system that the clinician already feels part of and turns to for support. Strengthening the network of clinical practice’s pedagogical knowledge and skills would develop a resource to which members of the social system would feel able to turn for ongoing advice and encouragement.

For a relationship to be sound, identification of responsibilities is crucial. In embracing the teaching that had been delegated to them, participants voiced a need for medical school to take responsibility for letting them know if they were indeed doing a ‘good enough’ job and to identify where they might be able to do better. In the presence of a nascent relationship with the medical school, this is an important responsibility that the medical school needs to accept. All teachers appointed at a medical school should be informed of how they will be evaluated by students. Faculty developers could play a role in informing clinicians of the results of that evaluation and offering further directed opportunities to strengthen any identified areas. This could serve to build a rewarding relationship between the medical school and their clinical teachers. It could provide the mechanism for acknowledging a job well done, as well as allaying uncertainties about the value of their current practice. Ensuring that the clinicians receive feedback about how they are doing in terms of medical school requirements, student evaluations and student performance would provide powerful input for directing their enthusiasm with regards to becoming better teachers25.

In his research, Billett considers the pedagogic practice most central for learning effectively in practice settings to be direct guidance by experts, who can use particular strategies to support the learning of particular kinds of knowledge, and utilisation of workplace activities that are inherently pedagogically rich4. The participants in this research function well as experts guiding the students and they have intuitively grasped that the student’s engagement in workplace activities is how learning may occur. Missing from their accounts was any mention of ‘particular strategies to support the learning of particular kinds of knowledge’, such as the strategies that are included in most faculty development for clinical teaching (eg feedback)15. One suggestion could be for specific evaluation tools to be incorporated into the medical school’s quality assurance of clinical teaching. These could then be used to meet the need expressed by participants for feedback on their performance as well as to hone offerings by faculty developers to address any particular developmental needs that arise.

An additional issue is less related to faculty development as such, but is related to relationships. The present study’s findings indicate that these clinicians would value being involved in the co-creation of a curriculum that would take into account the strengths and constraints of their clinical training platform. Frenk et al6 suggest that instructional reform calls for consultation between the education and health systems to deliver relevant medical education. This could be an opportunity to utilise the important perspective of those embedded in this different sphere of health care to deliver on the imperatives that led to extending the clinical training platform in the first place – namely strengthening the district healthcare system and preparing graduates for practice in contexts of primary and secondary care.

There are limitations to this work. This is a relatively small cohort of clinicians. The interviews were conducted by a family physician who had a role supporting some of the participants in their clinical teaching. All but two of the participants knew that the interviewer was working in faculty development. Despite this, the participants seemed able to express less positive opinions of the faculty around, for example, communication and acknowledgement. Six of the clinicians had completed a module on teaching and learning during their specialty training, and the group had varied exposures to the faculty’s educational development activities. These findings could therefore be seen to represent the best outcome of the faculty’s existing activities to strengthen clinical teaching.

Conclusion

In order for a medical school to be satisfied that the clinical teaching that it has delegated to clinicians at distant sites is as effective as possible, methods need to be found to engage with clinicians where they are as they seek ways of strengthening their pedagogical skills. McLean et al15 and Lieff16 refer to faculty development as change, requiring an open, conducive organisational culture of learning and responding to local individual needs. Faculty development initiatives have largely focused on those teaching within the physical spaces of a medical school. As the needs of emerging clinician teachers are identified, particularly those at geographically distant sites, that focus may need to broaden, embracing the interdependence of the health and education systems (as Frenk suggested6) to optimise clinicians’ existing clinical social systems. Wenger describes increasing the learning capability of social systems by providing genuine encounters among members where they can engage with their experience of the practice while attending to the social dynamics of that space in an effort to maximise learning capability21. Worley’s assertion that relationships do matter17 seems to have been validated in this group of clinicians. Clinicians’ desire for engagement seems to mitigate the professional isolation felt by many rural practitioners as shown in the literature on clinical continuing medical education programs for rural doctors26. This would suggest that faculty developers consider entering into existing social (professional) systems as mediators of learning capability and utilise a set of skills that may not traditionally be associated with the field.

The authors do not minimise the need to teach clinicians specific teaching strategies relevant to their workplaces. However, it is suggested that, in aiming to reach emerging clinician teachers in geographically distant contexts, there is a need for faculty developers to overtly utilise existing professional systems and design programs that attend to the foundational three Rs: relationships, responsibilities and resources.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief through the Health Resources and Services Administration under the terms of T84HA21652, in the Stellenbosch University Rural Medical Education Partnership Initiative.

The authors gratefully thank the research participants for giving their time, and Lynn Morkel for her editing advice.