Introduction

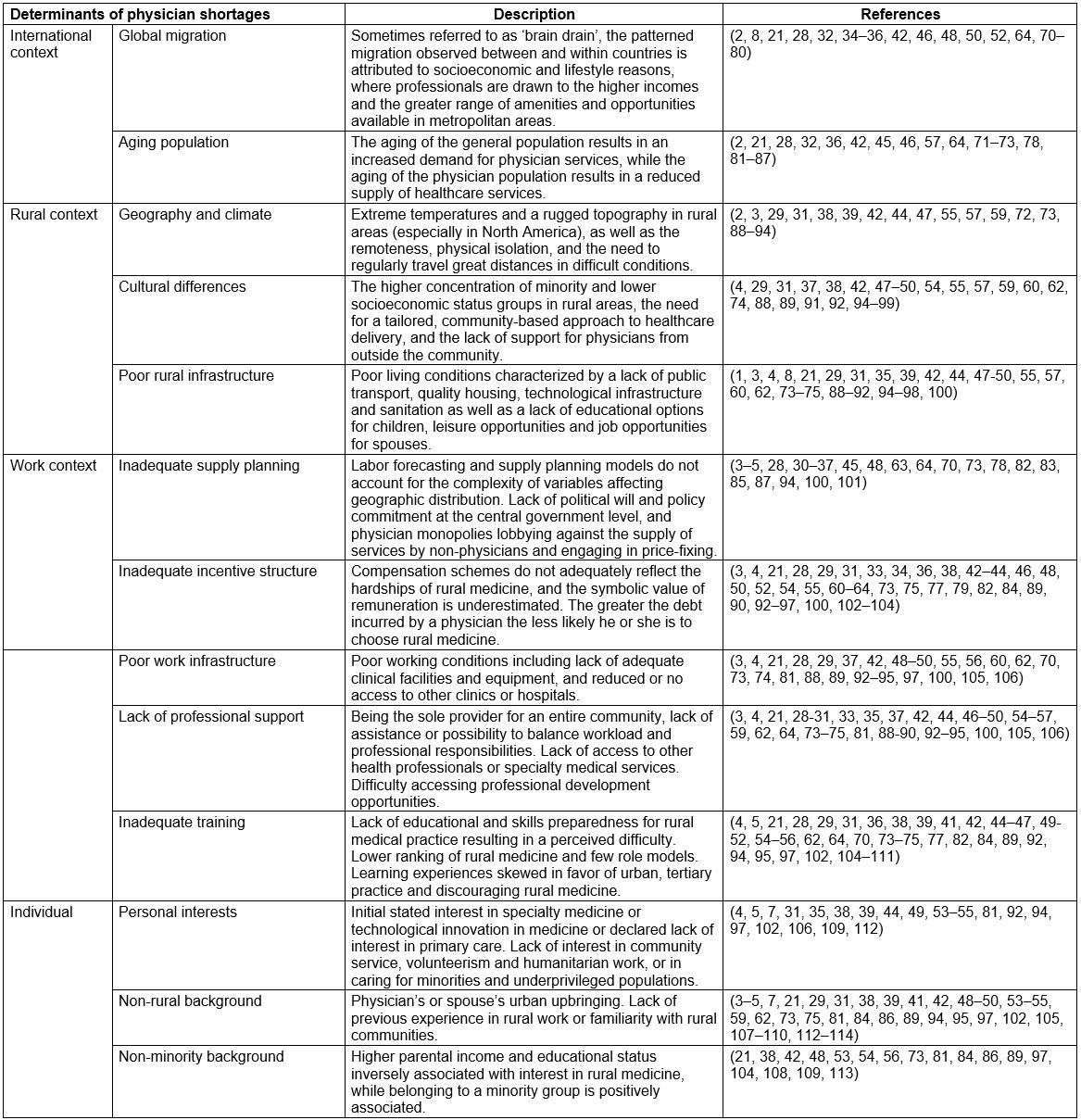

Physician shortages in rural regions are prevalent across OECD member countries. Due to the central role occupied by the physician in improving the delivery of and access to essential health services by disadvantaged populations, OECD member countries have devised various interventions to attempt to mitigate the shortage of physicians in rural regions1-3. Regulatory, financial, educational4 and tailored interventions are designed to encourage physicians to set up their medical practice in underserviced, rural or remote areas and at the same time discourage them from practicing in oversupplied, urban areas3. The interventions are subcategorized into 10 different strategies, described in Table 1.

However, no single intervention leading to a sustainable solution to the shortages of physicians in rural areas has been identified4. A recent OECD report describes policy responses as ‘largely conceived and implemented in the absence of evidence’3. One of the main critiques of existing interventions is that they rarely make reference to the determinants of physician practice location, so that interventions do not match the reasons why physicians may or may not practice in a given location5-8. In the field of public health evaluation, this reported weakness of the interventions is referred to as strategic relevance, a criterion that describes the coherence between the activities of the intervention and the target problem9,10. A corollary of the principle of intervention relevance is the idea that the causes of a problem are not equal; some may contribute more to the problem than others. The relevance of an intervention also refers to its consistency with the greater social context, and with an organization’s priorities and mandate10. For an intervention to achieve its intended results, it must be designed in a way that responds to the causes of the problem being addressed11.

Table 1: A description of the interventions to reduce physician shortages in rural regions

The objective of this research was to examine the strategic relevance of the interventions to reduce physician shortages in rural regions of OECD countries, first, by identifying the determinants of physicians shortages; second, by prioritizing the determinants; and, finally, by analyzing the interventions that have been implemented across OECD countries based on their ability to target the determinants of physician shortages in rural regions.

Methods

Strategic analysis is a type of program evaluation used in the health and social services to rank and order public health problems and their solutions, based on which of them need to be addressed first and how they will be addressed, while taking into account the needs of the target population.

Strategic analysis is intended to be an accessible evaluation tool for policy makers and evaluators in a workplace setting and therefore uses priority-setting methods that rely upon existing documents and/or expert opinion as the primary sources of information11. There are three main steps to conducting a strategic analysis. The first is to identify the set of problems that the intervention is intended to address. The second step is to prioritize the problems based on their relative importance and on the ability to intervene upon them. The third step is to analyze whether and how the intervention in question addresses priority problems11.

Step 1: Identifying the problems

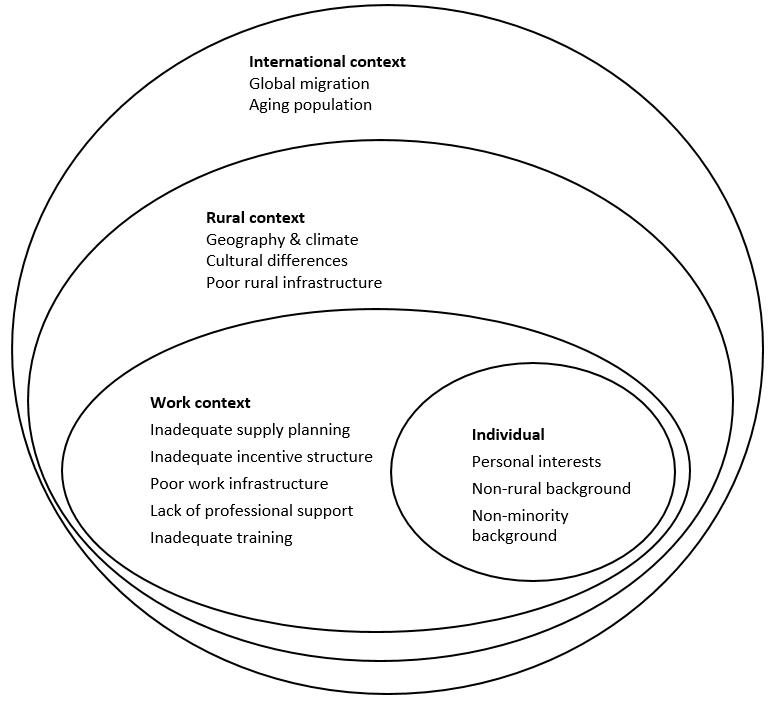

To identify the set of problems the interventions are intended to address, a literature review on the determinants of physician shortages was conducted. Publications were initially selected from the OECD and WHO research databases, using the key terms ‘causes/determinants’, ‘physicians/healthcare workers/healthcare personnel’, ‘geographic’, ‘distribution/shortage’ and ‘rural/remote/isolated/underserved/underserviced’. The citations of relevant publications were snowballed. This search was repeated in Medline including studies published between January 1995 and December 2014. Studies that examine non-OECD member countries were excluded, as well as those pertaining to non-physician health professionals. Studies pertaining to international medical graduates (IMGs) and associated regulation and procedures were also excluded because the use of IMGs is not among the interventions evaluated in this research (Table 1).

The method suggested by Mays et al in 2005 for reviewing qualitative evidence for management and policy in the health field was used to inform the inclusion of publications in the literature review12. A purposive sampling approach was thus used to identify publications based on whether they refer to ‘internal’ (individual) determinants or ‘external’ (contextual) determinants influencing physician shortages12,13. Purposive sampling makes use of large volumes of descriptive data, allowing for maximum variation, and the inclusion of studies that may otherwise be excluded from systematic reviews13,14. The most information-rich studies were included until a theoretical saturation was reached: when incremental learning became minimal due to the same determinants of physician shortages being repeatedly identified in the literature14,15. This was an iterative process involving all three authors, where disagreements or discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Step 2: Prioritizing the problems

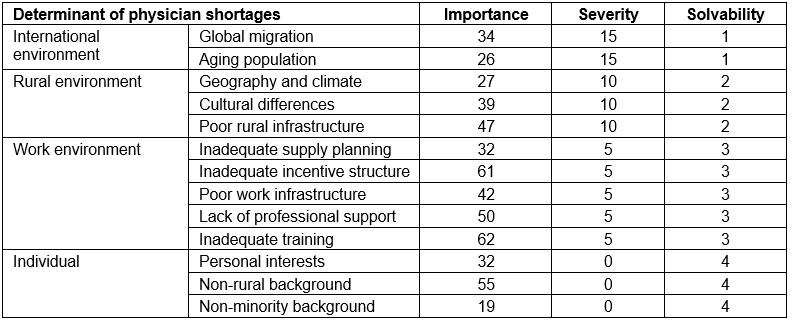

To prioritize the determinants of physician shortages three criteria were used: importance, severity and solvability16-18. Importance refers to the size of a problem.Severity refers to the seriousness of a problem and its potential impact. Solvability refers to the potential for conceiving and implementing solutions to the problem; in other words, how well a problem can be solved, if at all16,18,19.

The importance of a determinant of physician shortages in rural regions was based on the number of published articles identifying it as such. The articles were categorized according to the strength of the evidence they provide, based on the Cochrane Collaborative’s grading system for the quality of a body of evidence20. Descriptive studies or expert opinion were given a weight of 1, cohort or case control studies a weight of 2, and systematic reviews a weight of 3.

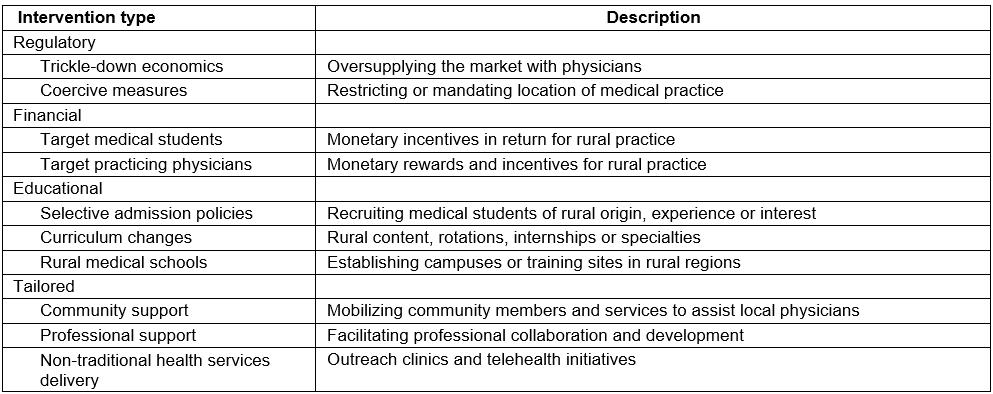

To determine the severity and the solvability of the determinants of physician shortages, a multilevel framework was relied upon (Fig1)6,21. This framework has previously been used to further understanding of the factors affecting the recruitment and retention of healthcare workers, but in low- and middle-income countries rather than in OECD member states21. Multilevel frameworks depict how individual behavior is influenced by structured contingencies, opportunities and constraints, within several layers of contexts22,23. Higher-level or contextual factors enable and constrain lower levels, or individual factors, and are the drivers of interactions among lower-level phenomena such as attitude and behavior24-27. This is a ‘top-down’ process referred to as embededness, where lower level factors take on the characteristics of and become aligned with the higher levels27.

The severity and solvability scores are based on the position of a determinant in the multilevel conceptual framework. Determinants situated at the outermost level of the framework are most distal from the individual, and exhibit the most constraining properties, not just on the individual, but on all the layers embedded within them. They are thus the most severe. However, these determinants lie outside of the realm of public health intervention and are considered unmodifiable, therefore the most difficult to solve18,28. The rural context is easier to intervene upon, followed by the work context, then individual determinants, which are considered the easiest to target through intervention programs29-31. However, individual determinants are less severe because they lack the constraining properties of higher level contextual determinants.

For these reasons, determinants situated at the individual level received a 0 for severity, at the work context level a 5, at the rural context level a 10 and at the international level a 15. Individual-level determinants received a solvability score of 4, work environment level a 3, rural context level a 2, and international context level a 1. A total score for each determinant of physician shortages was calculated by multiplying the sum of importance and severity by solvability: (importance + severity) x (solvability)16. According to established methods of strategic analysis, the determinants of physician shortages were evenly divided into four categories based on their total scores11. Priority level 1 determinants of physician shortages are those that should be targeted first through policy intervention, followed by priority level 2 determinants11. Priority level 3 determinants are those requiring further research, while level 4 determinants are of secondary importance in terms of research11.

Figure 1: Determinants of physician shortages in rural regions in OECD countries.

Figure 1: Determinants of physician shortages in rural regions in OECD countries.

Step 3: Analyzing the interventions

Each intervention was analyzed based on whether and how it addresses priority determinants of physician shortages. The content of included studies was analyzed as descriptive commentary from a policy analysis perspective14. This approach is used by case study researchers and policy analysts to answer ‘how and why’ questions, and provides insight into collective actions, organizational dynamics and institutional structures through descriptive interpretation of documents14. This was an iterative process involving all three authors, where disagreements or discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The final analysis was presented to a panel of four field experts, a health economist, a demographer/epidemiologist with expertise in rural and remote health, an evaluation and health policy specialist and a family physician/health administrator. All suggested modifications were incorporated in the final manuscript.

Results

A total of 97 articles were included in the review,including 14 systematic reviews and six cohort studies. The remaining publications were descriptive studies. Publications covered a wide range of disciplines: public health literature accounted for 33 of the publications, while 24 articles came from rural health journals; 20 from medical journals; 11 from the social sciences including economics, geography and sociology journals; and nine from the organizational sciences. The review identified 13 determinants of physician shortages in rural regions of OECD countries. A detailed description of the determinants is presented in Appendix I.

The determinants were categorized based on Lehmann et al’s 2008 framework describing the different environments affecting attraction and retention, as shown in Figure 16. The determinants were then prioritized according to the described method (Table 2).

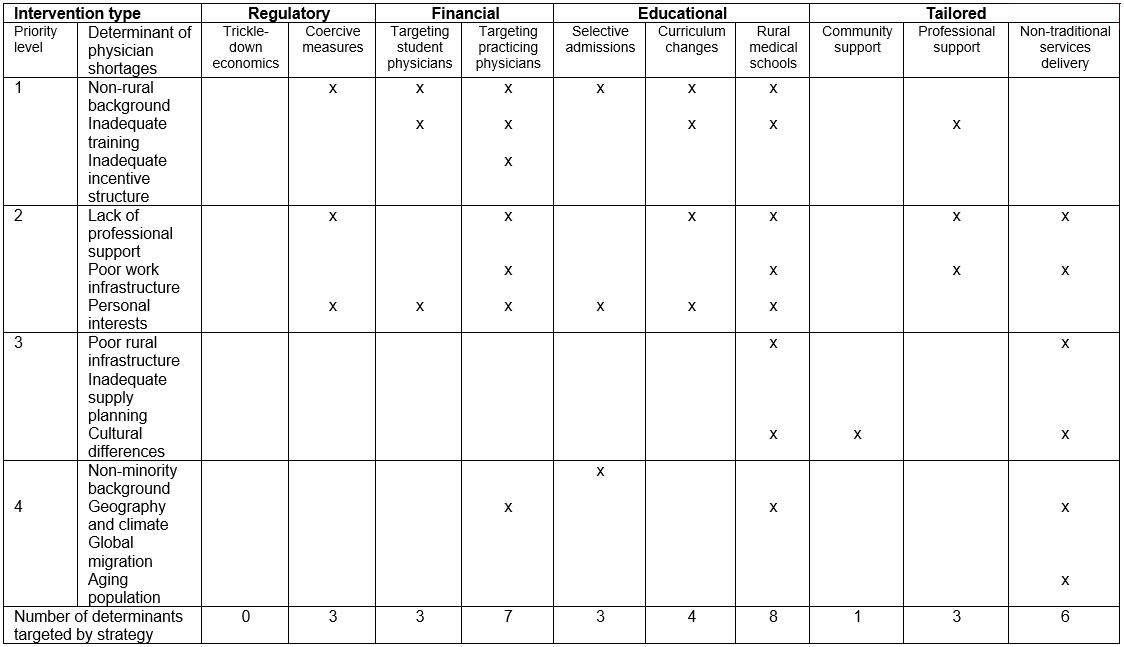

Finally, the interventions designed to address the shortages of physicians in rural regions of OECD countries were analyzed based on their ability to target the priority determinants. This is displayed in Table 3.

Table 2: Prioritization of the determinants of physician shortages in rural regions

Table 3: Analysis of interventions to reduce physician shortages in OECD countries

Regulatory interventions

Trickle-down economics: Trickle-down economic strategies do not respond to any of the causes of physician shortages in rural regions. Increasing the supply of physicians to rural regions is thought to be accomplished by increasing the overall number of individuals entering into a medical career32. However, the economic assumption that the oversupply of physicians will ‘trickle down’ to underserviced areas has been refuted33-35. Physician supply forecasting models have a limited ability to consider healthcare labour trends28,32,36,37.

Coercive measures: Intervention strategies that can bring the physician to a rural region may improve the chances that he or she will later choose rural medicine as a career. Several studies have noted a ‘dose–response’ relationship between the duration of exposure to a rural location and the likelihood of subsequently choosing rural medical practice29,38-41. Compulsory service in rural regions can result in a valuable learning experience serving disadvantaged communities, and a physician’s greater interest for rural health concerns and for primary care medicine4. Mandating rural medical service is a comparatively low-cost solution to increasing professional support for rural physicians3,8.

Financial interventions

Targeting student physicians: Scholarship or loans repayment programs are offered in exchange for rural medical service, which exposes medical students to rural life. This experience may dispel some of the negative stereotypes associated with rural medicine3. Associating financial reward with rural medicine is a form of institutional recognition that can improve the perceived lower ranking of rural medicine and stimulate students’ personal interests3,42. Students who participate in such programs receive more adequate training in rural medicine and are better prepared to practice43,44. Financial interventions are a relatively straightforward and quick method for relieving student debt and exposing students to rural medicine4,5.

Targeting practicing physicians: This strategy addresses the determinants of physician shortages in a similar manner to targeting medical students, while addressing an additional four determinants. The inadequate incentive structure of rural medicine is targeted through pay increases for rural physicians as implemented in a number of OECD member countries to reduce turnover in underserviced areas28. A variety of financial incentives are offered to differentiate rural physicians from their urban counterparts; these incentives include annual guaranteed minimum income, higher capitation payments, or premiums for regions with low patient volume3,45,46. Financing is offered to support locum programs and on-call duties, and for hiring nurses or physician assistants, which targets the lack of professional support44,46,47. Financial strategies circumvent some of the inadequacies of rural practice infrastructure through payment of expenses for medical equipment, or reimbursement for the setup costs of private practice3,46,48. Providing rural physicians with reimbursement for travel expenses can help ease the burden of being geographically isolated from family and friends49.

Educational interventions

Selective admission: Selective admission strategies target non-rural background. For example, ‘rural pipeline’ programs in Scotland and Japan recruit students directly from rural high school for entry into medical school3,39. In Canada, Australia and the USA, medical schools screen for a student’s personal interest in primary care, which studies suggest is a proxy determinant for interest in rural medicine50-52. The Rural Medical Scholars Program in Alabama, and similar interventions in Michigan and Missouri, screen for a student’s ‘humanitarian outlook’, and actively recruit students who have a demonstrated history serving the disadvantaged7,39,53,54. Selective admission strategies are unique in their ability to target rural areas with a high concentration of minority and/or low socioeconomic groups, as well as students from disadvantaged or minority groups. University of Manitoba’s Northern Medical Unit actively selects Aboriginal students for premedical preparation, and Australia’s Flinders University targets Indigenous Australians, a visible minority group that is underrepresented in medical careers7,55,56.

Curriculum changes: Studies show that medical students enrolled in a rurally focused curriculum are more likely to work in underserved areas than those in conventional medical programs46,50. Specialized curricula allow physicians to acquire the broad skill set necessary to practice medicine in a rural setting and produce graduates with locally relevant competencies4,50. Some medical schools in Canada, Australia, the USA and Belgium engage in partnership activities with rural health system personnel, thereby facilitating the creation of professional networks, collaboration and the increase of professional support for rural physicians50,56. Curricula that embed students early on in community and local clinics rather than in a university and hospital setting provide the type of hands-on experience that can increase interest in primary care, in rural medicine and in community service55,56.

Rural medical schools: Establishing medical schools, satellite campuses or ‘polyhealth’ clinics in rural regions is one of the costliest intervention strategies, because it involves an investment in infrastructure3,57. However, evidence suggests that it is one of the most effective strategies to reduce physician shortages, in part by prolonging their rural experience and minimizing exposure to urban distractions29,39,41. Rural medical schools eliminate, or greatly reduce, comparisons to urban practice, and expectations of urban teachers and staff, which can undermine a student’s rural inclination5,31,51,55. Physicians are not expected to automatically transfer the skills acquired through a conventional urban medical education to the rural setting, where advanced technology, equipment and specialized support may be unavailable4. Rural medical schools, with their faculty, staff, and professional and community networks, improve professional support in rural regions3. A campus or clinic strategically placed in a rural or remote region can widely disperse medical services to hard-to-reach areas57. This ‘medicalizes’ the region and makes it less isolated, in part by improving infrastructure8,28. Developing rural infrastructure improves the medical practice infrastructure of rural regions by facilitating the acquisition of equipment and technological and human resources4,57. Where research, training and partnerships are established between medical schools and local health systems, community engagement in health care increases, which helps to overcome the cultural difficulties that are sometimes reported by rural physicians4,39.

Tailored interventions

Community support: Programs in Australia, Canada and the USA offer community mobilization activities to foster cooperation between an incoming physician and community members28,48. Some interventions offer ‘health and wellbeing’ support by linking physicians to community resources58. Some OECD countries assist physician spouses to identify job opportunities28. The Southern Rural Access Program in the USA helps rural communities to recruit a physician who is ‘the right fit’ for their needs as well as providing technical assistance towards the enhancement of local capacities59.

Professional support: These intervention strategies encourage collaboration between rural health professionals and facilitate the creation of professional networks28. Some countries have introduced ‘model practices’ in rural regions, where the delivery of health services is shared among multidisciplinary teams, allowing for more flexible work conditions and improving the practice infrastructure in rural regions3. Such initiatives have been shown to enhance the technical preparedness of rural physicians byincreasing opportunities for consultation, research and professional development to physicians3.

Non-traditional services delivery: Non-traditional health service delivery are beneficial for remote areas with a high concentration of minority and low socioeconomic groups. Programs in Canada and in Australia allow specialists to travel intermittently to isolated regions, or where the population base is too small to establish permanent clinics3,4,45. Web services allow rural physicians to connect with other health professionals, thereby reducing professional isolation. Many OECD countries are investing in improving broadband capacity in rural regions to effectively use advanced technology, an important step towards improving practice infrastructure3,57. In Germany, rural physicians conduct ‘virtual visits’ with patients and communicate using e-health applications3. Studies suggest that telehealth networks in Canada have improved access to health care in Indigenous communities, who receive generalist and specialist consultations, and patient education through this intervention45. A digital platform was established in some rural areas to cut down on commuting time for home visits, especially for chronically ill patients, making it an effective approach to providing health care to an increasingly aging population57.

Discussion

This study presents a strategic analysis of the interventions to reduce physician shortages in rural regions of OECD countries by identifying the determinants of physician shortages in rural regions of OECD countries, prioritizing them and analyzing the interventions based on their ability to address the priority determinants of the problem. A link is therefore established between the determinants of physician shortages and the broad spectrum of interventions intended to mitigate them, addressing an important concern that has been expressed repeatedly in the literature3-8.

This research demonstrates that establishing medical schools in rural areas is the most strategically relevant intervention because it targets the greatest number of determinants of physician shortages and functions at multiple levels, by contributing to rural infrastructure, by engaging local communities and by improving the day-to-day experiences of rural physicians, rural medical students and their families. Such is the case of the Northern Ontario School of Medicine in Canada, which distributes medical training to more than 70 teaching and research sites across Northern Ontario, and which has demonstrated positive results in keeping graduates in rural regions45,51.

Financial interventions are the most commonly implemented in OECD countries3,48,60,61.This research sheds light on possible reasons for this: financial interventions target some of the most important, severe and solvable determinants of physician shortages. This study also reveals that financially targeting practicing physicians is strategically more relevant than it is to target medical students, who accrue greater benefit from educational strategies. Evidence suggests an important selection bias among students who participate in ‘return-of-service’ incentive schemes; these students would have chosen rural placements anyway8,43,50.

Non-traditional health services delivery strategies are shown to target a significant number of determinants of physician shortages at multiple levels, but outreach clinics have not been adequately documented in the literature and telemedicine has only recently gained attention as an important tool to improve health services delivery to rural and remote regions5,8,62.

Selective admissions policies are particularly useful in recruiting underrepresented groups into the rural medical pipeline, while community support strategies are the only interventions targeting the cultural differences that may deter physicians from accepting rural positions, or communities from welcoming new physicians. Professional support strategies target a small number of priority determinants of physician shortages, so may be best used in combination with strategies that target other determinants.

Regulatory interventions employing coercive strategies effectively target some of the determinants of physician shortages, but evidence suggests that they are disliked by both physicians and administrators8,50,63. Finally, laissez-faire regulatory strategies allowing market forces to dictate the geographic distribution of physicians have been shown to address none of the determinants of physician shortages and are therefore strategically irrelevant.

Two determinants of physician shortages are not addressed by any of the interventions: inadequate supply planning and global migration. A review of the tools and policies organizing physician labor supply and planning is required, as well as addressing the political opposition to innovative solutions to health services provision in rural regions, such as task sharing and skillmix64. Further research and policy development are needed to address the need for infrastructure and services development, and the lack of amenities and basic life needs,which drives professionals away from rural areas.

This research makes an original contribution to the rural health human resources literature by functionalizing the multilevel frameworks prevalent in the literature4,6,21,64,65. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to utilize this framework to categorize the determinants of physician shortages in OECD countries, and it is the first to use the framework as a basis for prioritizing the determinants, thereby achieving an evaluative exercise (strategic analysis}) rooted in theoretically established perspectives of a health human resources phenomenon.

An important contribution to the understanding of the determinants of physician shortages is made. As determinants move away from the individual level to more ‘distal’ levels of the framework, they become closer to being ‘fundamental causes’ of organizational or health phenomena66. Interventions that tackle fundamental causes of public health problems by altering the social, economic and political contexts have a greater potential for achieving success in the long term, even though these interventions may be more difficult to implement67,68. Agentic interventions, which focus on an individual’s choice to act, may be easier to implement but are also ‘temporary and palliative’, producing only short-term gains69. This point is worth noting when considering the persistence of physician shortages against the relative success of more complex, multilevel interventions, such as establishing medical schools in rural regions.

Limitations

The review of the literature is not a systematic review and is therefore not exhaustive. The aim was to achieve theoretical saturation in identifying the determinants of physician shortages in OECD countries. Although literature was deliberately selected from a wide range of disciplines, some relevant publications may have been excluded.

The prioritization method used to rank the determinants relied on the attribution of numerical values to represent the relative severity and solvability of the determinants. This was done to facilitate the calculation of a final score for each determinant. Further research is necessary to examine the validity of this scoring system.

Conclusion

Strategic analysis demonstrates that most interventions designed to reduce physician shortages in rural regions are strategically relevant because they address the priority determinants of physician shortages. A link is established between the determinants of physician shortages and the interventions, thereby addressing an important concern expressed in the literature. An original contribution is made to rural health human resources literature by relying on established theoretical frameworks to achieve a strategic analysis of the interventions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Doug Angus, Barthelemy Kuate Defo, Jean-Louis Denis and Carl-Ardy Dubois for their valuable comments on this research.

References

You might also be interested in:

2022 - Culturally sensitive care of Misak Indigenous patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Colombia

2014 - Community preparedness for highly pathogenic Avian influenza on Bali and Lombok, Indonesia