full article:

Introduction

Approximately 28.5% of the Australian population (6.9 million) was born overseas, and a further 20% has at least one overseas-born parent1, making Australia one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) countries. Diversity in language, religion, history and country of origin is increasing in Australia1. In the past, most Australian migrants, particularly humanitarian entrants, resettled in metropolitan areas where they had better access to various services and support systems2. More recently, Australian government policy has changed, with regional resettlement being advocated more3.

A combination of migration-related factors affect health needs of CALD populations and their ability to access appropriate services. These are particularly exacerbated among those with a refugee background as they have more complex needs4,5. Language barriers, the lack of information about services available, and culturally inappropriate care have been identified as factors that prohibit access to and utilisation of primary healthcare services among CALD populations6,7. An inability to successfully engage with health providers, a lack of culturally shaped information, and failure to effectively navigate the health system in a new environment affect people’s ability to make effective health decisions8.

Poor access to and utilisation of health services at the primary healthcare level has the potential to increase the reliance on and use of secondary and tertiary care, which in turn causes a higher financial burden to the health system9. In Australia, a higher utilisation of tertiary care by migrants compared to the general Australian population has been reported10. It is crucial for primary healthcare providers, including GPs, to better engage with CALD populations, and to consider clients’ cultural and linguistic backgrounds, and their levels of health literacy, in daily practice. The provision of respectful and culturally appropriate care that is based on cultural awareness and sensitivity is strongly emphasised in the Australian Standards for general practices11. It particularly advocates for patients’ rights to understand the information and recommendations they receive, and professionals’ obligations to use appropriate communication tools, including interpreting services for patients whose primary language is other than English and who have insufficient English literacy11.

Levesque et al (2013) define healthcare access as ‘the opportunity to reach and obtain appropriate healthcare services in a situation of perceived need for care’7. Accessibility is influenced by factors at individual, household, societal and physical environment levels. It is also affected by factors related to health systems, organisations and service providers7. Key factors at the health system level are the approachability, acceptability, availability, accommodation, affordability and appropriateness of services7. In order for the currently available services in Australia to be effectively accessible to CALD populations, they must be affordable and culturally acceptable and appropriate to meet the needs of CALD populations.

Guided by the above-described conceptual framework developed7, this qualitative study explored factors that influence access to and utilisation of health services among CALD populations in the south and east regions of South Australia (SA). Given the growing size of these populations in regional areas of SA, the findings from this study will inform policies and practices that can enhance the provision of culturally appropriate services. Improved access and utilisation will lead to improvement in overall health and wellbeing, in turn addressing the existing inequities in health among CALD populations.

Methods

A qualitative study was conducted between December 2018 and April 2019 to explore factors that impact on, and strategies to improve, access to and utilisation of health services among CALD populations in regional SA. Data were collected through: (a) individual interviews with service providers and key stakeholders; and (b) focus group discussions with members of CALD populations living in the study area.

Guided by the healthcare access framework7, the authors developed interview guides for both participant groups, then discussed and refined within the research team (Appendix I). These included questions on availability, accessibility, affordability and appropriateness of services provided to CALD populations in the region. Participants’ views on how the current services could be enhanced to ensure high quality and equitable access and outcomes for people from CALD background were also sought.

Key informant interviews

After the identification of the key informants, an invitation to participate in the study, along with the study information and consent form, was sent to a range of key stakeholders and service providers in the region. These included: (a) managers of general practices; (b) GPs and allied health professionals; (c) members of hospitals and community health centres of the South Australian Department of Health (Country SA Local Health Network); (d) members of local councils; and (e) members of community-based organisations working with CALD populations, including new migrants and refugee. A purposeful sampling12 was used by sending invitations to 48 people who were identified as knowledgeable in the area of interest. Of those invited, 23 people agreed to take part in a phone interview.

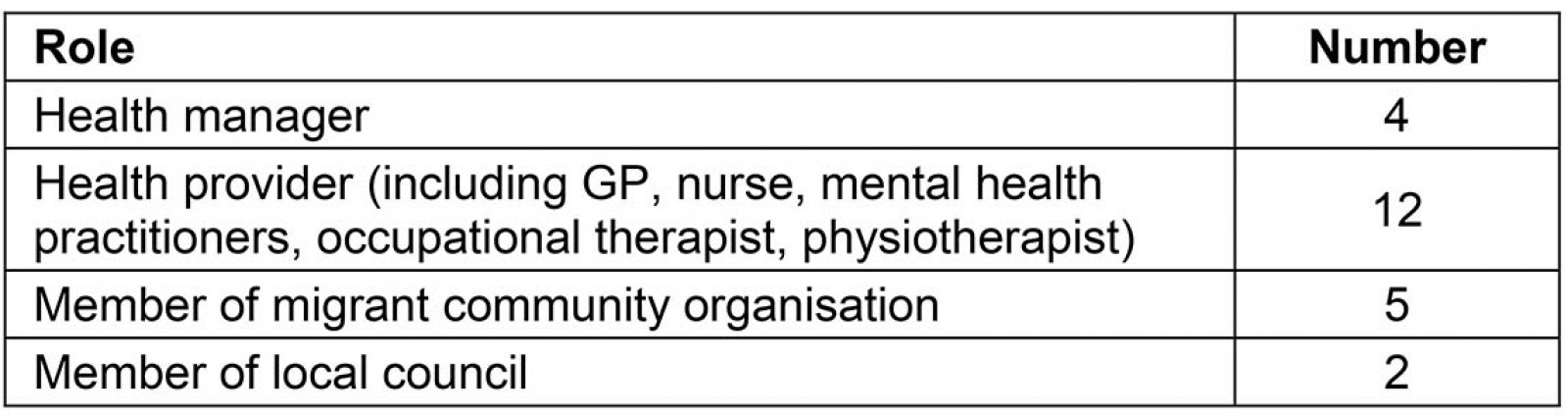

The numbers and roles of interview participants are summarised in Table 1.

Interviews explored participants’ perspectives on factors influencing access to health services for CALD populations, including individual, organisational and health system factors. Furthermore, participants’ views on strategies to improve issues of health service access and utilisation were sought.

Table 1: Interview participants’ role and number

Focus group discussions with CALD populations

Three regional towns with large CALD populations were selected: Naracoorte located on the Limestone Coast; Murray Bridge in Murray Mallee; and Renmark in the Riverland region. Familiarity with the regions by co-author KN, past experience of partnership with organisations and networks, and feasibility of access and travel to the sites within the project timeline and budget were other factors considered as selection criteria. With assistance from migrant organisations and community health centres, the authors promoted the study among local communities in the above towns. The study flyer, information sheet and consent form were translated into five common languages spoken by people in the region to facilitate community recruitment. The authors consulted with migrant organisations and health centres about the most appropriate cultural and gender composition of focus groups. To meet cultural needs, a gender-specific focus group was recommended in Naracoorte. A men’s group was held outside working hours to facilitate participant attendance. Mixed gender groups were felt to be culturally appropriate in Murray Bridge and Renmark. In Renmark, although both men and women were invited, only women attended the group session.

In total, four focus groups were held: two (one for men and one for women) in Naracoorte, one in Murray Bridge and one in Renmark. The largest CALD groups in each regional town were selected to represent CALD populations residing in each town. However, the authors acknowledge that the composition of focus groups in this study does not represent all regional areas in SA.

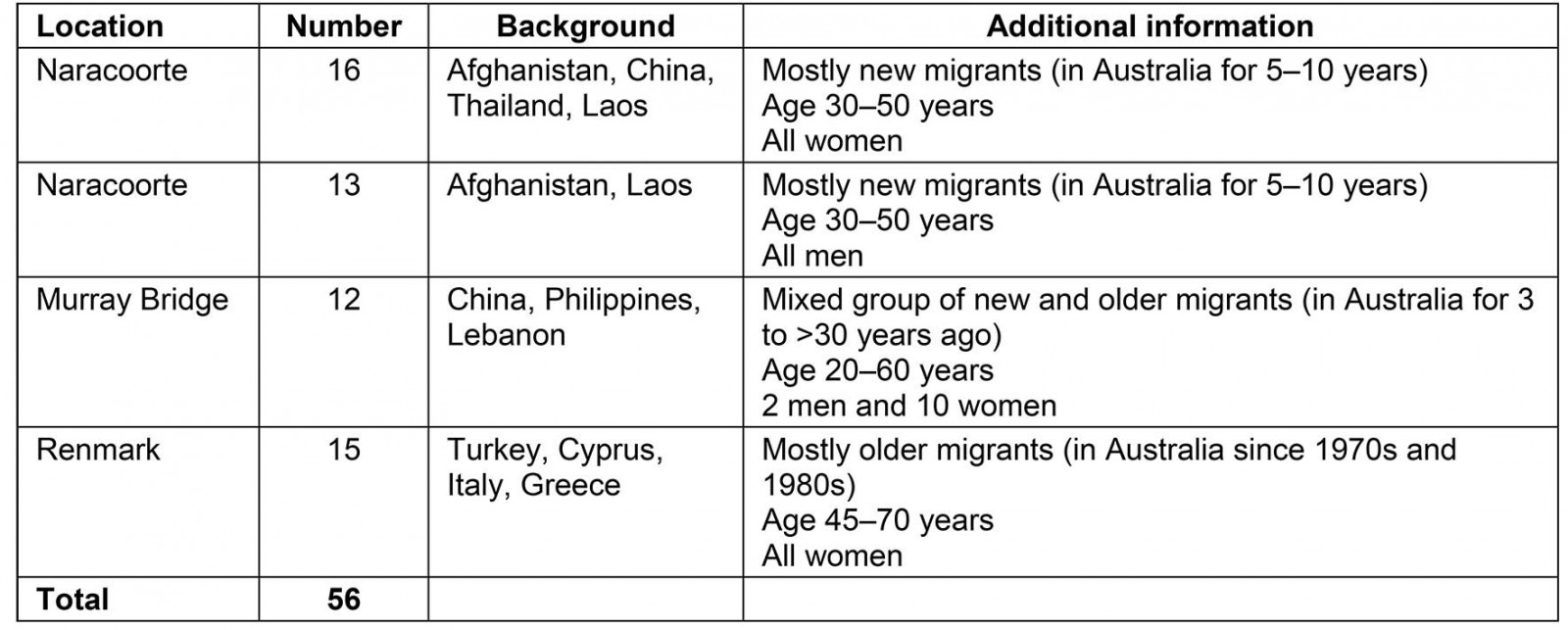

The number and composition of community members attending the focus groups are shown in Table 2.

Focus group participants were asked to share their experiences of using health services in the region and any factors that enabled or inhibited access to services. Additionally, discussions sought community views on how access to and utilisation of services could be improved.

The two focus groups in Naracoorte comprised mainly participants of Afghan background. First author (SJ), a native Farsi speaker, assisted with communicating and interpreting discussions during group discussions. Other participants from China, Thailand and Laos were fluent in English. In Murray Bridge, all participants except three of the Chinese participants were able to communicate in English. One Chinese participant fluent in English assisted in interpreting discussions where needed. In Renmark, bilingual workers from migrant organisations were present in the focus group and assisted in interpreting for Greek, Italian and Turkish participants.

Table 2: Location, number and composition of community members in groups

Data analysis

With participants’ consent, interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were transferred into the qualitative analysis software (NVivo v12; http://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo) to assist with data management and analysis. Inductive and deductive approaches were used to develop a coding framework and to analyse data13. The initial coding framework was developed deductively guided by the key elements derived from the Levesque et al conceptual framework7. Further codes were added, inductively, as they emerged from the interview and focus group data. The coding framework was discussed and refined in internal research meetings until a consensus was reached. As a result, some elements identified in the framework that were not directly relevant to the study findings were excluded from the data analysis and thus discussion of findings. On the other hand, a number of new concepts that emerged from the data, such as broader determinants of health, were added to the coding framework and discussed accordingly.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was sought and granted by the Flinders University Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee.

Results

A range of factors was found to be influential in access to and utilisation of health services by CALD populations. Although some issues such as distance and transport are related to geographical location and rurality, and thus applicable to the whole population, there were challenges specifically relevant to CALD populations. Key findings were categorised thematically: health literacy, service availability and accessibility, service acceptability, service affordability, and the broader determinants of health.

Health literacy

As shown in Levesque and colleagues’ framework, health literacy is one of the factors affecting patient perception of needs and desire for care7. Health literacy was a theme that strongly emerged from the study data. There was a consensus among participants that poor health literacy, including difficulties in searching and using health information, and seeking the right services at the right time were significant barriers limiting their ability to navigate the health system and utilise services:

Well, one of the key challenges would be them [people from CALD population] knowing where to go, communicating what the process is to do that and then, obviously how to navigate the system from there. (Health provider, ID#31)

Similarly, the community focus groups strongly echoed their experiences of challenges related to seeking information, understanding how the health system works, and finding appropriate services. Many focus group discussants reported relying on their children for health information. For others, GPs were the key source of information, albeit with communication challenges. While the use of the internet was reported to be helpful for some younger populations, it was noted that this was not accessible for older populations with poor digital literacy.

Several areas of concern were reported as factors leading to low health literacy. These included language and communication problems. Poor interpreting services, the complexity of the Australian health system, and poor availability of multilingual health materials for both health providers and community members were significant factors that were highlighted.

Language and communication: Almost all participants from both professional and community groups emphasised poor language and communication skills as barriers to health-seeking practices, understanding the health system, and poor patient–provider communication and relationships:

I will certainly see clients who will travel to Adelaide because the doctor speaks their language. That’s very true. So language is an important one. (Health provider, ID#6)

Focus group participants provided examples where poor English proficiency prevented them from effectively searching and understanding the health information and services, and communicating with health providers:

The major problem for us is about translation. Most people here can’t speak English and if you don't speak English, it is very hard to understand anything. (Community focus group)

Interpreting services: The study identified interpreting services as a widely used strategy to overcome communication problems. The benefits of, and challenges associated with, the availability and quality of interpreting services, using family members to assist in translation, and the lack of willingness by some providers to utilise interpreting services were themes frequently emerging from the study:

Obviously, we rely on the interpreter services to assist us with all communication and without the phone communication interpreter service we couldn’t function as a general practice … we need to keep good telephone interpreter services going. (Health provider, ID#23)

While some participants felt satisfied with the interpreting services, others pointed out some concerns. One GP commented on the time delay for an interpreter to join the appointment online:

We would arrange interpreting service but there’s always a big time delay which is a significant challenge. Often in general practice you've got 15-minute appointments and you're already running late … sometimes it could take five minutes of just sitting there waiting for the interpreter to come online. (Health provider, ID#20)

The quality of interpreting services to make sure messages are appropriately translated and conveyed caused some levels of uncertainty and distrust in some health providers:

I just never had that full confidence that what I was asking was definitely getting across. I would ask what I felt to be a fairly simple question and then the interpreter and the patient could be having quite a long dialogue and I’m thinking what are they talking about, what’s going on … (Health provider, ID#21)

This was particularly important in the area of mental health: ‘a lot gets lost in terms of communicating feeling and meaning’ (Mental health provider, ID#31), or ‘Even with the interpreter, some of the context got lost a little bit which is problematic in [the] area of mental health’. (Health provider, ID#22)

Feedback from community members indicated a considerable gap between the demand and provision of professional interpreters, with a number of participants from community focus groups reporting examples of where the lack of interpreting service made it difficult to communicate: ‘most of them don’t use interpreter, so I don’t understand really’. Another participant from a community focus group believed that interpreting services are available ‘only for GPs’ and that funding for interpreting services for allied health providers, including psychologists, is lacking.

For those with limited English skills, the lack of interpreting services equated to missing a medical appointment:

A couple of times I went all the way to Mt Gambier and there was no interpreter, so I had to come back and did nothing. (Community focus group)

The use of relatives, friends or children as interpreters was noted by a number of participants. The major area of concern was around ethical and confidentiality issues related to the presence of children or non-professional interpreters in the consultation session and their involvement in a patient’s health issues:

… and it’s the teenage children who are often used as the interpreters, which is quite difficult if it’s a very adult conversation to be had. There has been the sustained use of children as interpreters in health situations that is so totally unhealthy for the children. (Migrant health organisation, ID#3)

Challenges in relation to the use of phone interpreting services in regional areas compared to onsite interpreters were stated as a barrier both in terms of technical aspects and building rapport and relationships.

Use of bilingual health materials and health providers: Participants frequently mentioned the importance of multilingual materials as a strategy to improve health literacy among CALD populations and their understanding of health conditions. Increased investment to make bilingual health materials widely available to health providers was highly recommended:

That might be a really good opportunity if the GPs to be made aware of some of the resources that are already available freely on the internet. Just being able to have a whole heap of resources so we can give patients a piece of paper in their language or something with lots of pictures … (Health provider, ID#21)

However, it was acknowledged that due to the variety of languages spoken by CALD populations, and the range of health conditions, it is not always feasible to make translated materials available in all languages and settings.

Despite the importance of bilingual workers, this study revealed that their use varied, and was mainly applied on an ad hoc basis. While a few participants reported the existence of bilingual health providers in their services, many felt that regional areas lacked enough bilingual health providers. As noted by a health manager:

I look around my health service and it’s predominantly coming from the dominant culture, the majority of our workers. (Health manager, ID#14)

Disease prevention and health promotion: From the perspectives of some participants, placing more emphasis on health promotion, including group activities, would not only prevent the need for acute care but also provide an opportunity for the community to build relationships and enhance their health literacy through connection with other people and health services. This, in turn, would improve the approachability and acceptability of health services:

They all probably know when they’re sick they need to go to the doctor or the hospital, but it’s the preventative stuff and just keeping healthy, I suppose. That might be really useful for them, and giving them access to some of those sorts of things might be more useful than just waiting until they get sick. (Local council, ID#20)

Service availability and accessibility

Most of the access issues that emerged from the interviews and focus groups were related to geographical distance and applied to the broader rural population, and were not limited to CALD populations. These included access to GPs, allied health professionals and specialists; high turnover of health providers in regional areas; long distances to travel to access services; and poor transportation.

Accessibility of primary and tertiary health providers: The shortage of GPs, allied health professionals and specialists was one of the most frequent themes reported by study participants. This led to long waiting times, lack of choice, poor continuity of care, and poor after-hour services. Community members provided examples of situations where their access to health services, including GPs and allied health, was lacking or very limited:

If you want to see the doctor you want, you have to wait for like three to four weeks. Sometimes three months, and sometimes you can’t even make an appointment, especially if you want to see a specialist. (Community focus group)

High turnover of health providers: Community members from all three study sites expressed concerns in relation to the high turnover of doctors in regional areas. This was partly because service providers are usually GP registrars who often stay in the region for a short term, as they are required to relocate to different locations or practices to complete procedural, non-procedural, community service and/or research needed for their training. The transient mode of service by GP registrars, while helpful in the short term, significantly compromises the continuity of care, relationship building and service quality and satisfaction:

When you see a doctor you think they will be there for a while and then 6 months or a year later you ring to make an appointment and they then say oh that doctor has gone and they send you to another doctor and then you lose that doctor again. (Community focus group)

A health provider confirmed:

The clinic at the moment is pretty well staffed by registrars and they change all the time, and a lot of them are mostly overseas people I think. They come and go too. So there’s no continuity. (Health provider, ID#20)

Issues around access to specialist care were, to some extent, overcome through regular specialist visits to rural areas. Despite the high level of satisfaction by participants for having specialists onsite, the frequency of visits and long waiting lists have remained challenging, leading to limited access to the services. The use of technologies such as telecommunication tools and video-conferencing was also noted as useful in improving rural communities’ access to specialist care.

Distance and transportation: Transport as a barrier to access emerged as a key issue from both interviews and community focus groups. Although transport was felt to be more of an issue related to the geographical location and distance in rural and regional areas, it was acknowledged that for CALD populations, with poor English and communication skills, there is added complexity in finding existing facilities, and organising appointments and travels.

If they need to get access to services away from here – travel is always an essential thing that they need to try and access, and I think it may be a challenge. Because there are a lot of things to organise, and with the language not always being perfectly understood, to organise an appointment at a different place and time and then making them aware that they need time to travel and maybe even time to stay overnight. (Local council, ID#11)

The main options for transport to access health services were private car, taxi, public transport, community transport and state-funded transport facilities. There was a strongly held view that poor access to public transport is a major barrier to transportation. Most participants had to use private cars or taxis or rely on their children or family members for travel:

It is very hard to go to Adelaide, it is far about 4 hours. There is no public transport, we have to drive ourselves. (Community focus group)

The cost associated with transport (for example, using a private vehicle or taxi) was also pointed to as a major barrier:

Well, some people just can’t do that. Or they – if they are working, for them it’s a massive financial – what’s the word – burden, because it’s a day off work, It’s travel; it’s accommodation for some people if they’re having to go to Adelaide. (Health provider, ID#31)

There are currently some schemes in place to support people requiring transportation to access health services. For example, the Patient Assistance Transport Scheme in SA14 provides subsidies to assist those who live in rural SA to access necessary and approved medical specialist services not available locally. However, it was evident from this study that not all eligible clients are aware of such a scheme and have not had any experience of using it, mainly because of a lack of information provided by health providers or health services.

Service acceptability

Cultural needs: Community members particularly commented on gender issues as an important cultural factor that prohibited effective access to health services. While in many cases, clients were asked about their preference on provider gender, female doctors were not always available when needed, as indicated by a community member:

There are a few female doctors here but it is not enough. We go to Mt Gambier or Adelaide sometimes to see a female doctor but in emergency situation there are male doctors or there are nurses. (Community focus group)

Mental health is a particular condition where there might be vast cultural differences in the way it is approached. As commented by a number of health providers, cultural factors played a role in people’s health-seeking behaviour and utilisation of mental health services. The existence of stigma attached to mental health problems in some cultures, regardless of service availability, acceptability and quality, prohibits people’s ability to seek and reach mental health services:

I think there’s some cultural – I don’t know if the word’s concerns, for some cultures accessing psychology can be a concern. Maybe, so lack of understanding, for want of a better term, of what we could actually do to assist people. (Health provider, ID#31)

As shown below, the lack of cultural competency was also echoed in a comment provided by a community member:

We need a GP who understands us and be kind to us and to be experienced. Some of the doctors here (not all of them) don’t have enough experience about working with non-English people. I don’t know what their training is. (Community focus group)

Health providers’ cultural competency: One of the key themes emerging from interviews with health providers was poor cultural competency among health providers. Almost all the health providers interviewed noted the lack of, or one-off, cultural competency training provided to health professionals to enhance their cultural understanding and capability of working with CALD populations:

We are all supposed to be doing mandatory training with regards to CALD and/or Aboriginal cultural difference people. But I must say that the focus is mainly on dealing with people from Aboriginal origin rather than people from other regions in the world. (Health manager, ID#17)

Service affordability

Direct and indirect costs of health services, poor access to bulk-billing general practice services, and out-of-pocket payments were some of the major issues noted by both service providers and community members:

In Adelaide and major cities, you have people who do bulk-billing. That doesn’t happen in Naracoorte. (Migrant health organisation, ID#3)

Limited numbers of bulk-billing practices resulted in long waiting lists:

A dietician, if you’re prepared to pay you can see them fairly soon but other than that, you might wait three or four months to see a dietician. (Health provider, ID#20)

Some groups of migrants do not have access to public health insurance (Medicare), meaning that they have to pay medical and pathology fees out of their own pocket. This was noted by both health providers and community members to be ‘unaffordable’, ‘very costly’, ‘a financial barrier’, and ‘hard to reach’.

A mental health provider working in a private service stressed cost as the key reason why people in low socioeconomic conditions, including CALD populations, do not access their service:

To be honest that’s something that is a concern, we don’t actually get to work very often with people of different backgrounds. That’s not saying we don’t want to but there’s obviously a gap and because we are a fee for service, the negative of that is it costs to come to us. (Mental health provider, ID#31)

On many occasions, the cost of visiting a health provider and travel-related costs were significant reasons for non-attendance by CALD populations:

Eligibility for our services, and for the more free side of our service is that you have Medicare, but we would offer it to you if you don’t have Medicare but you’d have to pay, and I would think that most people would then say no thanks, and likely end up in one of our hospitals. (Health manager, ID#14)

Broader determinants of health

Narratives from participants demonstrated issues concerning social determinants of health that affected their ability to access the services, as depicted below.

Employment and income: Employment status and income of people living in the areas under study varied. Naracoorte, for example, was reported to have the ‘lowest unemployment rate in Australia’, with the majority of migrants moving to this regional town because of existing job opportunities in the wine, wool and meat industries. Nevertheless, the seasonal nature of the work opportunities made many people struggle to secure income outside of the work season:

When they’re not working in the vineyards, they’re on Centrelink, because they can’t easily access other part time jobs, but the economy requires that they stay here to be available for the next round of seasonal work. (Migrant health organisation, ID#3)

Even those in paid jobs experience inappropriate working conditions such as long hours, labour work and mistreatment, which negatively impact on their health and wellbeing:

I think employment in particular is a huge vulnerability for people of migrant backgrounds. And then in turn that really affects their health in terms of working long hours, working unsociable hours, working in unskilled, manual labour jobs for longer than they should be, the stress of not having enough money, and maybe knowing that they’re not being treated the best way but feeling stuck as well. I think that’s pretty significant. (Mental health provider, ID#31)

Housing: Housing was another well-known social determinant of health noted by participants:

If we can’t get accommodation, like healthy accommodation in place for people, safe accommodation then it doesn’t really matter how much money we throw at their health care because we’re missing the basics. (Health provider, ID#22)

There is shortage of rental house. Some people here don’t like to sell or rent their houses to Afghani people. (Community focus group)

Racism and social isolation: Racism, social isolation and a lack of social support groups were other social determinants identified as barriers to accessing services and/or better health outcomes. Those who have limited English proficiency have a higher tendency to isolate themselves from society due to the difficulties in communication15. This can have a negative effect on their physical and mental health. These determinants were reported by some participants as factors impacting on their health and ability to seek or access health services:

The community is – like many rural communities, they have a strong identity and a sense of boundaries about who’s in, and who’s not in. So there were tensions in the community. (Migrant health organisation, ID#3)

Despite the recognition of the importance of social determinants on migrants’ health, there was a general view that the current health system is lacking a holistic approach to address those determinants through intersectoral actions:

I don’t know that it’s a strategic approach to how we work together across sectors, across social and health sectors, to provide that joined up holistic care around people’s health determinants, and who’s going to play what role. And down on the ground it’s not joined up either. (Health manager, ID#14)

Discussion

The findings of this project are consistent with other studies reconfirming a multitude of barriers that continue to impede CALD populations’ access to and utilisation of health services6,16,17. Language and communication barriers, health literacy, difficulties in navigating the health system, and poor cultural competency of service providers were shown as major factors hindering access to services. Challenges related to geographical location and rurality such as transport, availability of specialist and allied health services, and associated costs, are additional challenges that CALD populations living in rural and regional areas face. It is, however, recognised that distance and transport in particular were not issues affecting CALD population alone, but these apply to the broader population living in rural and remote areas.

Poor health literacy consistently emerged as a key factor affecting accessibility and was identified by both health providers and community members. Any effort to raise the health literacy in these populations will require actions at different levels and points in time16,18. The provision of general support services during the initial settlement phase to improve people’s understanding of the available services and to navigate the health system is crucial. Migrant organisations already play some role providing such support and building capacities within their communities. However, there are limitations on their scope of practice, coverage and resources. Allocation of specific roles within health services or migrant organisations as the first point of contact for CALD populations when they arrive in the region to carry out vital work has the potential to overcome the existing knowledge gaps in these communities19,20.

Communication barriers were found to be a major challenge for CALD populations to access health services. Consistent with Levesque and colleagues’ framework7, further efforts to enhance the ability to engage, strengthen and improve access to language services and strategies to recruit and retain bilingual health providers are necessary, if accessibility to services by CALD populations are to be made. Similarly, improvement in communication tools such as telecommunication and making the translated health materials widely available to health providers would also be an effective strategy to address access to and utilisation of health services. Service affordability is also critical, requiring policy support to improve access to bulk-billing health services for CALD populations.

It is well acknowledged that for the healthcare system to be culturally competent, it is important for clients and service providers to engage effectively, through mutual understanding of what is being communicated21, which is possible only when both sides can understand each other. For this study, the findings revealed significant gaps in health providers’ knowledge and understanding of cultural needs of the communities they serve. This highlights the importance of developing a cultural competence framework that guides the provision of services for CALD populations, and allocating resources for health providers’ training in how to deal with the growing number of CALD populations in regional areas is required.

Additionally, other strategies need be developed to improve access and improve cost effectiveness of health care delivery for these populations. For example, planning and implementation of health promotion activities at primary healthcare settings not only will reduce demand for costly care at the tertiary level, but is proven to be effective in improving engagement with communities, social inclusion, and building relationship and trust with health providers and systems22. As described by Levesque et al, health promotion activities can also increase approachability and acceptability of health services.

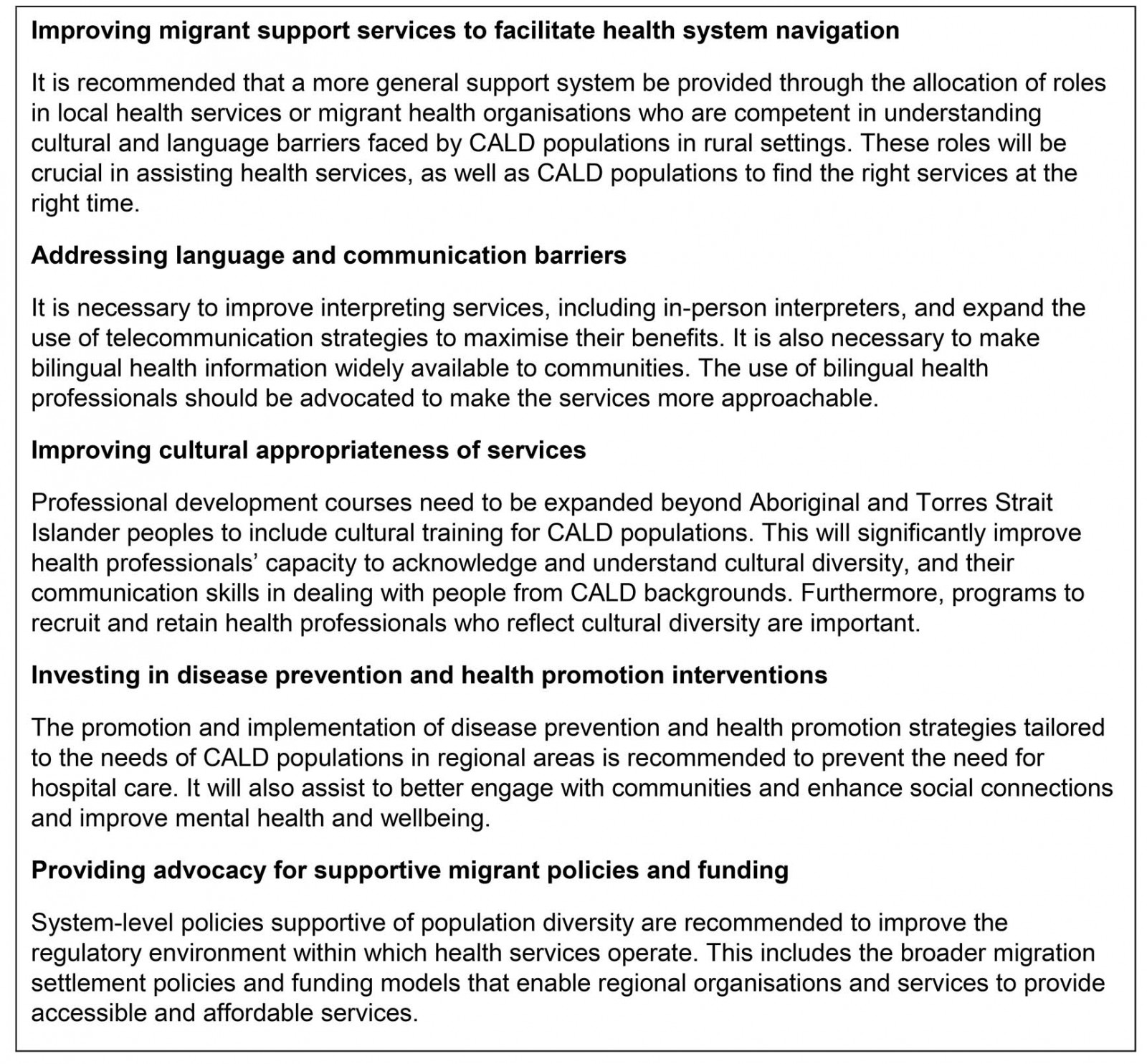

Moreover, it has to be acknowledged that in addition to health system barriers, the broader determinants of health continue to impact on the physical and mental health of disadvantaged population groups, including those of CALD background23. For example, housing, transport and employment are major determinants influencing peoples’ access to and affordability of services. Addressing these determinants and developing programs in collaboration with other social sectors is essential in order to improve overall health and wellbeing of CALD populations in regional areas24,25. This study provides recommendations on how to improve health literacy, system navigation, and access to health services for CALD population living in regional areas (Box 1).

Box 1: Recommendations to improve access to and utilisation of health services by CALD populations

Box 1: Recommendations to improve access to and utilisation of health services by CALD populations

Strengths and limitations

It is important to acknowledge that this study has some strengths and limitations. The use of qualitative methods through engagement with service providers and community members provided an opportunity to gather detailed information and stories, and to triangulate data26. Engagement with migrant organisations and community health centres as well as translation of community materials facilitated engagement with and recruitment of community members. GP recruitment was, however, challenging, partly because of their heavy workloads in regional areas. Although much effort was made to increase engagement of community members during focus groups, some participants contributed less to the discussions. Cultural factors, language barriers and the lack of experience in participating in group discussions about health and health services may explain the lesser engagement of some participants. Furthermore, some comments provided by community members in different languages may have not been accurately interpreted during the translation process. This was a small study in part of regional SA and thus its generalisability to other settings with different socioeconomic and population profiles may be difficult.

Conclusion

This study revealed key factors facilitating or constraining access to and utilisation of health services by CALD populations in regional SA. A combination of strategies at different levels of health services is required to ensure services are accessible, culturally appropriate, acceptable and affordable. These are critical to reduce inequity in health access and outcomes among the growing CALD populations in Australia.

Acknowledgements

This project was commissioned by the Country SA Primary Health Network (CSAPHN). We acknowledge the support received from individuals and organisations in the search setting in promoting the study and recruiting participants. We also acknowledge participants who served in the region in different roles, and members of CALD populations and organisations who shared their knowledge, stories and experiences with us.