full article:

Introduction

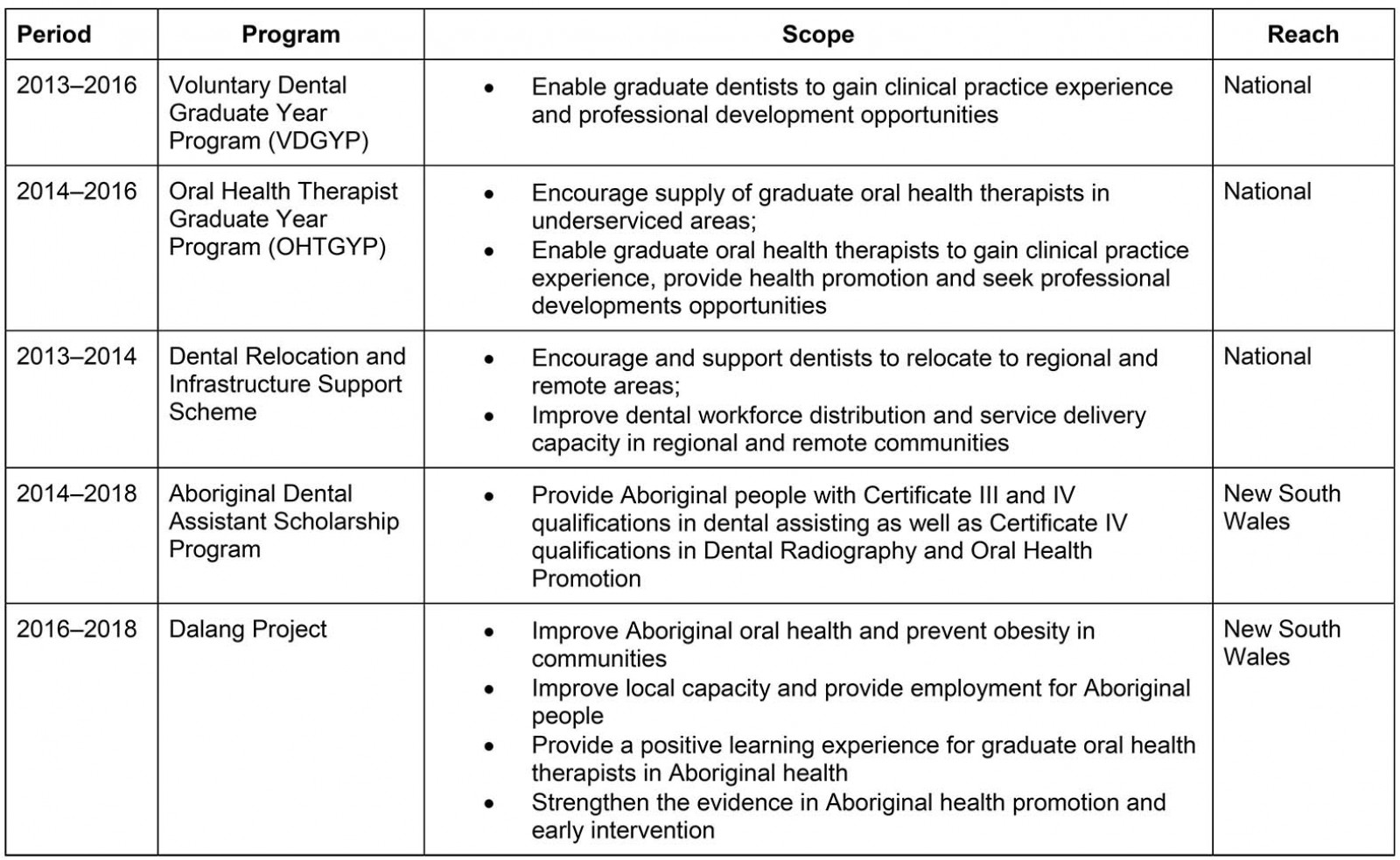

Dental professionals in Australia are unevenly distributed across major cities and regional and remote areas1. This uneven distribution greatly underserves the Australian Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander population, of whom 62.6% live in regional or remote areas2. Recently, the Australian Government implemented several oral health workforce initiatives including the Voluntary Dental Graduate Year Program (VDGYP) from 2013, the Oral Health Therapy Graduate Year Program (OHTGYP) from 2014, to increase the oral health workforce in regional and remote areas3-5.The development and support of these programs expand oral health service delivery to underserved Aboriginal communities. It is a key strategic direction of the New South Wales (NSW) Aboriginal Oral Health Plan6 and supported by the NSW Ministry of Health (MoH).

The VDGYP and OHTGYP provided service delivery funding for a community oral health service in Central Northern NSW for Aboriginal people. The oral health service was co-designed by the Poche Centre for Indigenous Health at the University of Sydney and two local Aboriginal Community Controlled Aboriginal Health Services (ACCHSs) in the region and commenced service delivery in 20147. The service was supported by the MoH, which provided pilot funding.

As a result of Commonwealth budget cuts, the VDGYP and OHTGYP were both ended prematurely. This decision, however, was neither evidence-based nor supported by the public oral health sector8,9. The cessation of these programs adversely impacted oral health service delivery in regional and remote areas and among ACCHSs who have less economy of scale than larger Local Health Districts (LHDs) to absorb the loss of service delivery. The impact of the closure of the VDGYP and OHTGYP on NSW ACCHSs was raised during the NSW Aboriginal Oral Health Workshop in 2015 as a key issue for ACCHSs. This led to the co-design of a small-scale oral health therapy graduate year program for ACCHSs, known as the Dalang Project, between the Poche Centre for Indigenous Health, NSW ACCHSs, Nepean Blue Mountains LHD and the MoH. The MoH agreed to fund the project as a pilot for 12 months initially.

The Dalang Project is an oral health and obesity prevention program targeted towards Aboriginal children in NSW. Graduate oral health therapists are employed and hosted in ACCHSs within NSW for 12 months and provide equal amounts of oral health service delivery and oral health promotion. The Dalang Project commenced in 2016 and ran for three full years (2016 to 2018) with scale-down funding for the first 6 months in 2019. The Dalang Project ended in the second half of 2019.

The project had four key aims:

- Improve Aboriginal oral health and prevent obesity in communities.

- Improve local capacity and provide employment for Aboriginal people.

- Provide a positive learning experience for new graduates in Aboriginal health.

- Strengthen the evidence in Aboriginal health promotion and early intervention.

The Dalang Project placed equal emphasis on oral health service delivery and oral health promotion. Oral health therapists provided 2.5 days per week of oral health service delivery and 2.5 days per week of oral health promotion. This model was unique as it enabled oral health therapists to engage with local Aboriginal communities and implement culturally competent, practical and evidence-based oral health promotion solutions. The Dalang Project aligned with the professional development and workforce strategies of the NSW oral health plan (Oral Health 2020: a strategic framework for dental health in NSW) as it provided a consistent approach for a graduate program with a strong continuing education and development component10.

Oral health promotion delivered as part of the Dalang Project aimed to enable Aboriginal communities to lead the implementation of evidence-based oral health promotion strategies in schools, improve access to culturally competent oral health services, increase fluoride use in Aboriginal children and families, improve water availability in schools and communities, and encourage water consumption among Aboriginal children. These aims were achieved through engaging the local Aboriginal community to identify a target school and implement evidence-based strategies to meet the needs of the specific community. Evidence-based oral health promotion strategies included dental screenings and referral to the local ACCHS for dental treatment, supervised in-school toothbrushing programs, structured fluoride varnish programs, distribution of free toothbrushes and fluoride toothpaste, installation of freestanding water fountains in schools and communities, and structured in-school water bottle programs.

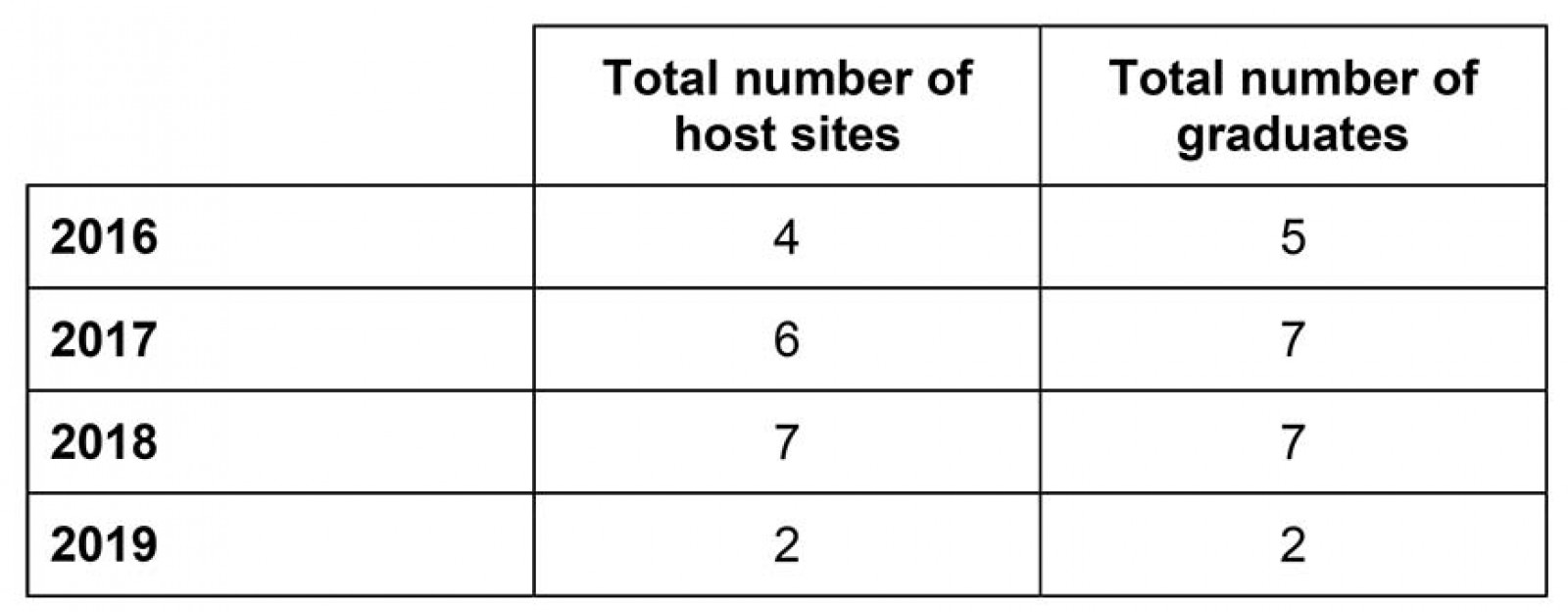

The Dalang Project commenced in five host sites in 2016 and expanded to include two additional ACCHSs in 2017. In 2018, seven oral health therapists were employed in seven ACCHSs across NSW. In 2018, the program was not renewed for a 2019 intake. As a result, 2018 graduates were offered an extension for 6 months in 2019, with two graduates taking up this offer.

The aims of this evaluation is to determine the level of satisfaction of graduates and host site supervisors with the Dalang Project and whether the program expanded local oral health service delivery capacity and employment in rural and regional areas of NSW. The Dalang Project has contributed to improved oral health status and oral hygiene behaviours in some locations and this has been reported elsewhere11.

Methods

Each year of the program an expression of interest was sent out to all ACCHSs with a dental service in NSW to participate in the Dalang Project. Criteria for selecting a host ACCHS included suitable clinical facilities, ability to provide adequate clinical supervision, agreement to implement the Dalang Project oral health promotion program and agreement to employ a local Aboriginal dental assistant or trainee. Graduate oral health therapist positions were advertised by the Poche Centre for Indigenous Health and applicants were selected by a panel of representatives from partner organisations.

Graduates were required to participate in planned professional development activities four times each year and to participate in weekly teleconferences to discuss issues and clinical practice. Senior clinicians participated in these meetings to provide clinical advice that utilised regular teledentistry sessions.

To evaluate the Dalang Project several methods were used. This included an analysis of oral health workforce programs over the past 5 years and their relationship, if any, to ACCHSs, and to state and national strategic plans for oral health and the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to provide context for the evaluation of the Dalang Project. All graduates of the Dalang Project were invited via email and social media to complete an online survey, created using SurveyMonkey12. The survey included questions about their year in the Dalang Project, why they applied, what they liked and disliked about the project, where they planned to work post-placement, and examples of the most significant changes they observed in the communities where they were placed. The questionnaire was based on a similar questionnaire used to evaluate University of Sydney dental student rural placements over the previous 9 years13. The total number of host sites and oral health therapists each year is provided in Table 1.

Host site supervisors and staff were also asked to complete an online survey that examined their overall satisfaction with the project, and any examples of the most significant changes they observed or received reports of in their local community.

Service delivery data was collected from each host site and reported in terms of Dental Weighted Activity Units (DWAUs). The DWAU performance measure is used by the Australian Government to measure the performance of state and territory public dental services against the Dental National Partnership Agreement14. It is also used to measure the performance of public dental services within LHD and ACCHS dental services funded by the MoH15.

All oral health promotion delivered as part of the Dalang Project was recorded weekly into a database using Microsoft Excel software via a teleconference with all graduates.

Table 1: Number of host sites and graduates by year

Ethics approval

The Dalang Project and the evaluation of the project were approved by the NSW Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council (AH&MRC) Ethics Committee (1281/17).

Results

Graduate survey

A total of 15 of the 19 (79%) graduates completed the graduate survey. The majority of respondents were from the last two full years of the program: 2017 (n=6) and 2018 (n=7). Only two graduates from 2016 responded to the survey. Dalang graduates who participated in the survey were between 22 and 28 years of age. Of the 15 respondents, 13 were female, one male and one other.

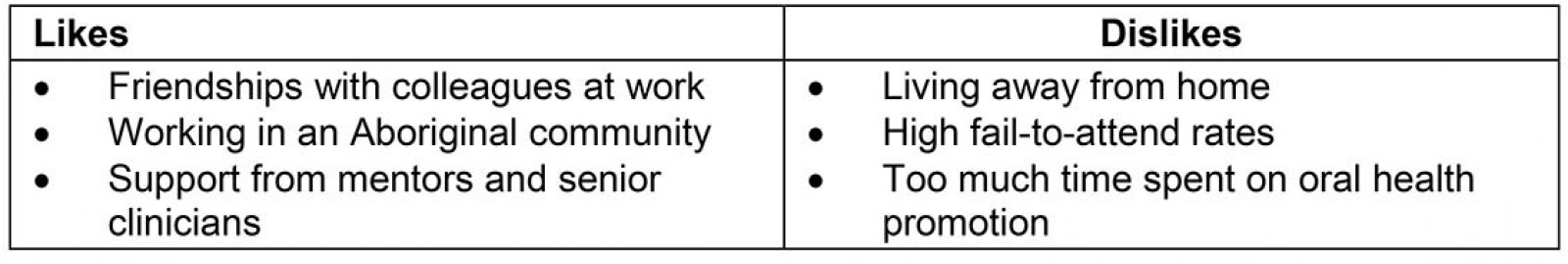

The majority of graduates found out about the Dalang Project through the University they trained at. Their main motivations for applying were to work in an Aboriginal community or an interest in Aboriginal health and working in an Aboriginal community (n=7) and/or to work in a rural area (n=3). Other motivations for applying including mentorship (n=1) and an opportunity to be more independent (n=1).Table 2 demonstrates aspects of the Dalang Project graduates liked and disliked.

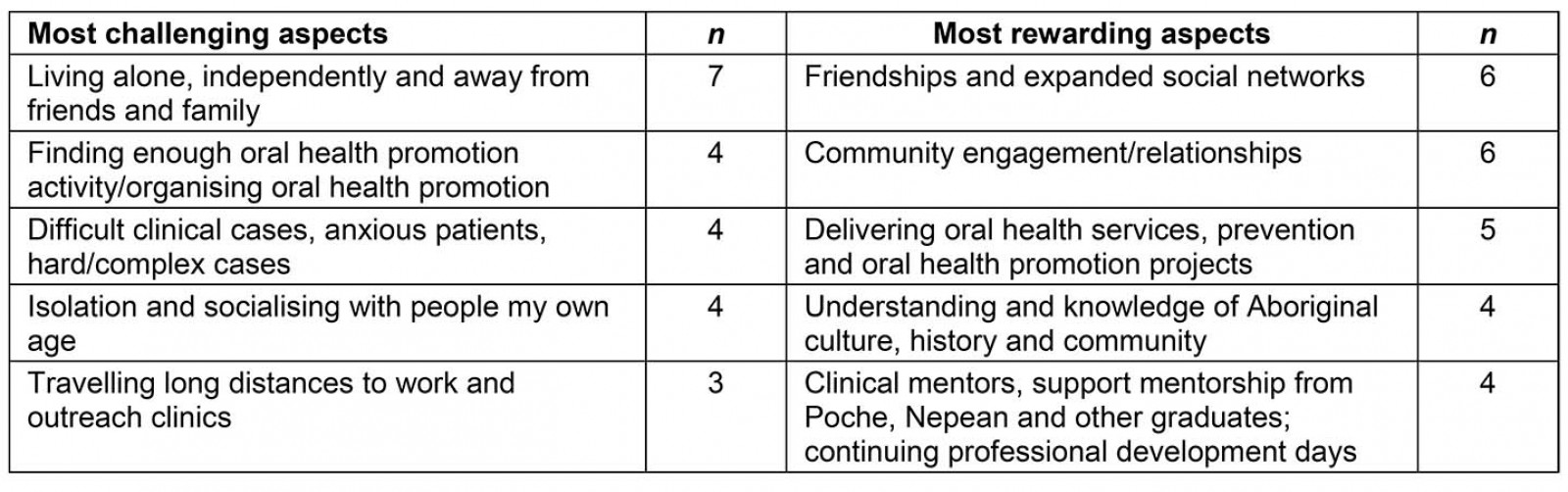

Graduates were asked about the most challenging and rewarding aspects of their graduate year. These responses are summarised in Table 3.

Graduates were asked whether the Dalang project had benefited them and, if so, how. One respondent said:

… it helped me grow as a person. I am now more independent and flexible. I have also grown in confidence in regards to my clinical skills. I also established connections with other professionals and made many friends from different backgrounds. It had been a year that I will always remember for the rest of my life.

Another respondent said:

I gained so many new experiences both clinically and culturally. I’m very proud of myself for getting through this year and I’m grateful that I was given the opportunity to possibly help reduce the caries incidence in Aboriginal communities and promote better oral health awareness.

Graduates were also asked ‘What specific personal and oral health skills did you acquire or improve upon during your Dalang Project graduate year?’ Responses included:

I definitely learnt how to communicate and socialise better with people from all walks of life, especially because I've come to find that people in the country are more open to conversation than my people in Sydney.

OHP [oral health promotion] program development and implementation. Extraction of baby teeth. Thorough assessment and diagnosis of oral health conditions.

Personally, I built on my cultural competence skills as well as broadening my mindset of treatment for Aboriginal communities. In the clinic I realised that not everything you learn at University is applicable and you have to learn how to adapt to the situation given to you and provide treatment that’s in the best interest of the patient and their needs.

Prior to commencing the Dalang Project only 4 of the 15 respondents came from rural or regional areas. Nine of the 15 respondents were considering working in a regional, rural or remote area prior to applying for the Dalang Project. Eight of the 15 respondents said that the Dalang Project made them reconsider their future and they were now considering working in a regional, rural or remote location. Twelve respondents were working at the time of the survey and half were working in regional, rural or remote location in NSW and one in the Northern Territory.

All reported that they would be more likely to work in an ACCHS as a result of being a part of the Dalang Project. The majority of respondents would recommend the program to future graduates.

The majority of graduates rated the Poche Centre’s overall management and coordination of the Dalang Project as ‘very good’ to ‘excellent’ (n=11), The remainder (n=4) rated management and coordination as ‘good’.

Graduates were asked to suggest how the Dalang Project could be improved. Main suggestions included increasing the amount of clinical time (n=4) and keeping the program going (n=2).

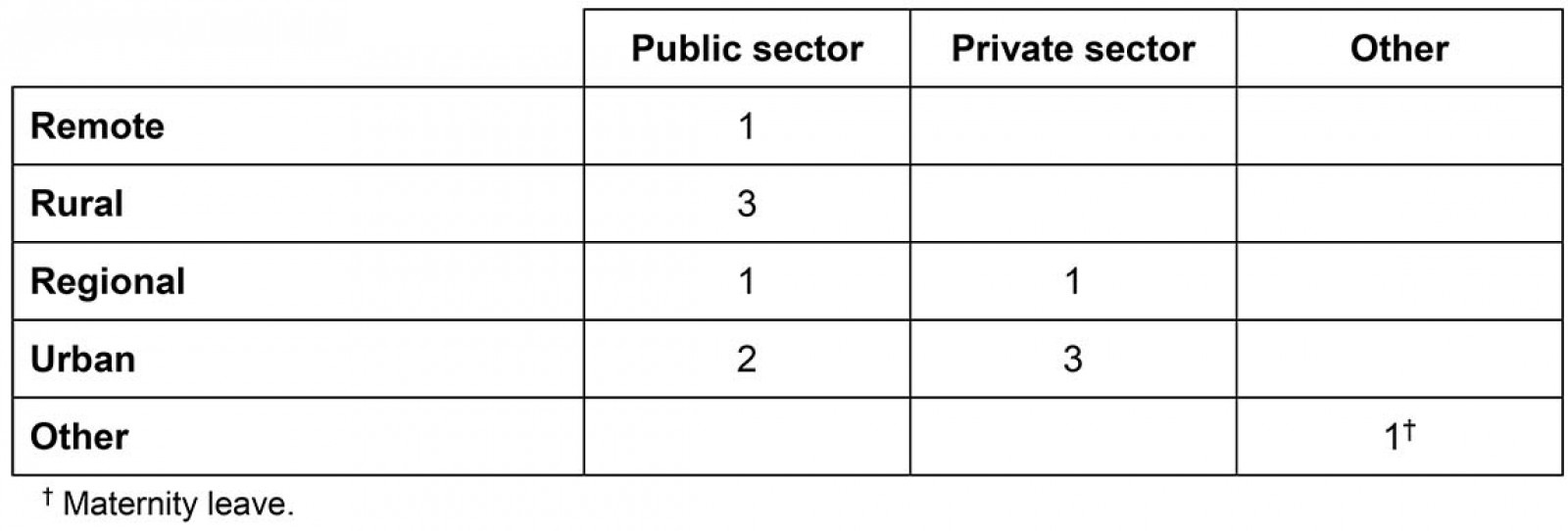

Table 4 summarises the postgraduate year employment outcomes for graduates of the Dalang Project. The majority continued their employment in public sector regional, rural or remote areas.

All graduates rated the quality and usefulness of their continuing professional development days as either very good (n=6) or excellent (n=9).

Table 2: Graduates’ main likes and dislikes about the Dalang Project

Table 3: Most challenging and rewarding aspects of the Dalang graduate year

Table 4: Postgraduate year employment outcomes

Host site supervisor survey

Eight host site supervisors responded to the management survey. Positions included chief executive officers (n=2); practice managers (n=2); clinicians (n=3) and senior dental assistants (n=1). Main factors for host sites to participate in the Dalang Project included a funded oral health therapist to provide dental treatment (n=5), to conduct school screenings and providing oral health promotion (n=4), and addressing high waitlists for dental treatment for children (n=2). All respondents rated the support from the Poche Centre for Indigenous Health as good, very good or excellent. All respondents agreed that travel, mentorship, regular contact from the Poche Centre for Indigenous Health and face-to-face time with other graduates was helpful for the graduates. Six respondents believed it was easy for graduate oral health therapists to be involved with the project and the majority (n=5) believed the best thing about the Dalang Project for graduates was gaining experience. Two respondents reported that the down time due to two and a half days dedicated to the delivery of oral health promotion was the worst thing about the Dalang Project for clinic staff. Suggestions to improve the Dalang Project included continuation (n=3), nothing (n=2), increased clinical time (n=1), flexibility if oral health promotion days are not utilised (n=1), and the option for oral health therapists to attend different training courses (n=1).

Oral health service delivery

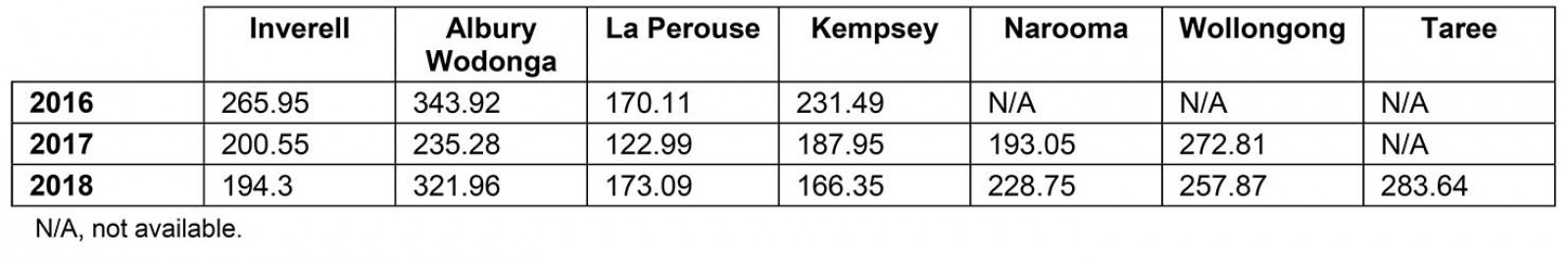

Oral health service delivery (clinical dental treatment) is measured in DWAUs and can be broken down by date and provider name for each host site. The Poche Centre collated monthly reports on DWAUs from each ACCHS to ensure treatment targets were met. The target for each graduate was 20 DWAUs per month (240 annually) and these were in addition to the annual DWAU performance target each ACCHS has set by the MoH.

Table 5 summarises the DWAU total provided by the graduate clinician at each site for 2016, 2017 and to 30 June 2018. In a 12-month period (1 May 2016 – 1 May 2017) the Dalang Project provided a total DWAU value of 1199. The Dalang graduates provided dental care in fixed clinics, and in several sites mobile dental vans were used. Overall, Dalang graduates therefore contributed substantial additional oral health service delivery for their host ACCHSs, particularly given most of the host services are small sites and only have two to three dental chairs each.

Table 5: Dental Weighted Activity Units for each host site by year

Oral health promotion

Across the seven host sites, nine target schools were identified by the local Aboriginal community. At each target school, oral health therapists delivered a comprehensive suite of strategies including in-school toothbrushing programs, installation of water fountains supplemented by water bottle programs, distribution of fluoride toothpaste and toothbrushes, dental health education and the regular application of fluoride based on existing protocols co-designed by the Poche Centre for Indigenous Health with other Aboriginal communities in NSW16. A total of 63 schools, 21 preschools and 15 community health services also received regular dental health education through the Dalang Project. A total of 3250 toothbrushes and fluoride toothpastes packaged in a hard-plastic storage container were distributed to children and families through the Dalang Project.

A key part of the program was the installation of refrigerated and filtered water fountains in schools where there was no free filtered or refrigerated water supply. The inclusion of this component in the program was part of the co-design process, links the program to the wider population health strategies in NSW to help prevent childhood obesity and supports a common risk factor approach to the prevention of non-communicable diseases in children. All water fountains installed through the Dalang Project do not remove fluoride. As part of the installation process, written approval from the school was required. Three water fountains were installed in target schools during the Dalang Project.

Discussion

The early cessation of the OHTGYP and VDGYP had a substantial impact on ACCHSs in NSW as several had taken on graduates under these programs. The Dalang Project was the only remaining oral health workforce program assisting ACCHSs in providing additional clinical and preventive services that also provided graduate oral health therapists with valuable experience providing oral health service delivery and oral health promotion in Aboriginal communities (Table 6). Overall, the supply of oral health professionals has improved in rural and regional areas of Australia in the past decade17; however, the supply is still lower in remote areas of Australia1.

Recent systematic reviews related to educational placement programs of dental professionals have identified there is a lack of evidence related to actual employment outcomes, with the majority of studies only considering intention to work rurally 18,19. However, the Dalang Project reported on actual workforce outcomes and demonstrated that the project was successful in attracting new graduates to rural and regional areas of NSW, with many remaining in these areas after the program (Table 4). This suggests that new graduate programs are still an important strategy for the public dental and Aboriginal community-controlled sectors.

The majority of the Dalang graduates found the project rewarding professionally and in gaining a better understanding of Aboriginal culture and working in an ACCHS (Tables 2,3). While many Dalang graduates struggled living away from friends and family, this was balanced by new friendships and expanded social networks (Table 3). This aligns with positive and negative experiences of rural placement initiatives for dental and oral health students, with social isolation and being away from friends and social networks common concerns20,21, and a friendly rural community often reported as a key positive22,23. Clinically, graduates noted the challenge of complex cases and the rewarding aspects of mentoring in addressing these challenges. Clinical experience and clinical mentorship are commonly reported key positive aspects of educational dental initiatives 13,18,22,24.

The Dalang graduates reported that positive and negative aspects of the experience may provide an insight to the enablers of and barriers to working rurally; with a recent dental study interviewing graduates almost a decade after graduation, and reporting that broad scope of clinical treatment and professional mentorship were key enablers to rural employment, proximity to family and friends was a prominent barrier25. It would be valuable to follow up the Dalang graduates at several time points to investigate their career trajectory and apply interviews to explore their employment decisions and the factors involved. This exploratory research would provide important insights to add to the limited evidence base.

The Dalang Project was well received by both the oral health professionals and the Aboriginal community controlled health sector. The Dalang Project was also recognised as a case study in the MoH annual report in 2017, along with the Aboriginal Dental Assistant Scholarship program26. Each year the project was refined with stakeholder feedback. This included introducing the MoH initiative Make Healthy Normal into all oral health promotion activities27. The expression of interest guidelines for host sites were updated to allow for greater weighting for areas of need to ensure that the same sites weren’t necessarily selected each year. Presentations on progress of the Dalang Project and its success were given at a variety of forums including the NSW Oral Health Conference in 2017, the State Oral Health Executive of NSW in 2017 (this group includes all NSW public dental health directors and general managers from each LHD) and the NSW Oral Health Advisory Group (the key oral health advisory group to the MoH) in 2017. Host ACCHS sites were supportive of the program because of the experience it gave new graduates along with the mentoring via the Poche Centre.

An unexpected benefit of the Dalang Project was that the graduates provided the oral health workforce to improve the reach of ACCHS oral health programs. This included the use of several mobile vans that had previously been under-utilised to provide outreach services. The Dalang Project was used as a foundation for a pilot, school-based fluoride varnish program in which trained Aboriginal dental assistants applied the varnish28. Graduates assisted with recruiting schools into the study, undertaking oral health assessments of students and overall local project management. A recent study in an area where Dalang graduates were based found improvements in oral health status and oral hygiene behaviours of Aboriginal children due to oral health promotion programs similar to the ones they had helped deliver11.

Overall investment by the MoH in non-government organisations (NGOs) for oral health activity totaled A$6.6 million in 2016/17 and A$6.8 million in 2017/18 out of a total NGO funding of over A$150 million26,29. The Dalang Project cost approximately A$940,000 per annum to run, with most of these costs being for the salaries and on-costs of the graduate oral health therapists. The Dalang Project exceeded all performance targets associated with the program and it was highly productive against the DWAU targets used for all oral health NGO programs funded by the MoH (Table 5).

In late 2018, as part of the year-to-year review of the project, the MoH decided not to support continuation of the project in 2019, providing direct support to the ACCHSs. Given the oral health needs of the Aboriginal population and the demonstrated success of this program there is a strategic need to have several strategies, including the provision of comprehensive, culturally competent and sustainable oral health promotion. Such a strategy is consistent with the strategic directions of the NSW Aboriginal Oral Health Plan6, Oral Health 202010 and the National Oral Health Plan30. There is good evidence that oral health therapists are a cost-effective alternative to dentists in delivering oral health prevention services programs, as are dental assistants31, which concurs with the findings of this study.

A limitation of this study is that the majority of the respondents were from the previous two full years of the project (2017 and 2018), and this may impact on some of the findings. This reflects the follow-up method for the graduates and that more recent graduates were easier to contact by email or social media.

Table 6: Major Australian oral health workforce programs, 2013–2018

Conclusion

The Dalang Project is an example of a successful co-designed project that has positively impacted oral health service delivery for Aboriginal children and has provided a valuable experience for new graduate oral health therapists working in ACCHSs. Overall, the Dalang Project was found to be a positive professional experience for the oral health therapists, with many remaining in rural, remote and regional locations after completing the program. It was valued and its continuation supported by ACCHSs.