Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of global morbi-mortality. It is characterized by its impact on a population’s lifestyle and high costs to households and health systems. CVD occurs in developed countries as well as in countries with medium and low incomes, such as Mexico1,2. CVD is multifactorial because it has genetic, demographic and lifestyle components3,4; it has been predicted that by the year 2030 more than 23 million people will die from CVD5.

According to the Pan American Health Organization, the World Health Organization and the World Population Prospects 2015, rates of premature mortality due to CVD in Mexico increase with age; CVD is the fourth largest cause of death in the 34–44 years age group, the third largest cause of death in the 45–54 years age group and the leading cause of death in the ≥65 years age group6-8.

In agreement with data from the national survey of health and nutrition in Mexico (ENSANUT 2018–2019), in adult women the national prevalence of abdominal obesity was 88.4% (95% confidence interval (CI) 87.2–89.4), while the prevalence of overweight and obesity by body mass index (BMI≥25 kg/m2) was 76.8%. The national prevalence of hypertension by previous medical diagnosis was 21.9% (95%CI 20.6–23.1), reported in 34.5% of the urban and 32.7% of the rural population. Regarding diabetes mellitus, 14.4% of adults over 20 years of age presented a previous diagnosis. As of the year 2000, diabetes mellitus is the leading cause of death in women and the second leading cause of death in men. It is one of the five diseases with the greatest economic impact on the healthcare system. Nationally, 30.4% of adults (31.2% of women) have elevated cholesterol or triglyceride levels9-11.

In Mexico, Indigenous women in particular have greater conditions of social vulnerability, such as a lack of medical services and gender inequalities that promote bigger disadvantages in access to health services in the Mexican health system12.

Social determinants of health and the risk factors for the development of CVD have been evaluated individually and jointly with different tools, to get an accurate diagnosis. The Framingham risk score (FRS) has been widely used to relate biochemical and clinical factors to calculate the risk of CVD in 10 years in the adult population13-15.

However, access to biochemical data of CVR is sometimes difficult in rural communities and triggers the need to develop and validate alternative anthropometric tools to predict the risk, especially in populations with restricted access to health services, in rural or Indigenous areas16.

Several anthropometric indexes have been proposed as CVR predictors. Among them, waist circumference (WC) has been used most frequently to diagnose central obesity. It can also be related to CVR biomarkers17. Evidence has shown that waist–height index (WHI) and conicity index (CoI) are sensitive anthropometric predictors in the diagnosis of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and CVD, since they both consider height in the identification of chronic non-communicable diseases18-20.

In public health, according to epidemiological terms, one of the challenges in interpreting results for the diagnosis is the sensible and proper discrimination of positive or negative cases. Therefore, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves have been used to compare the predictive ability of diagnostic tools, through their graphic representation, by considering the balance between sensitivity and specificity, as well as to obtain cut-off points to support the diagnosis21.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the predictive capacity of three anthropometric indexes to identify cardiovascular risk (CVR) in Indigenous women of the Matlatzinca community in Mexico. This community is characterized by levels of poverty and social inequity that make access to CVR biomarkers very difficult.

This study is part of the multidisciplinary scientific project ‘Mesoamerican maize and its scenarios for rural development’, financed by the National Council of Science and Technology, which includes some diverse research on social processes and strategies for the defense of native corn by ethnic groups and peasant societies in the State of Mexico. The research is one of those contributions that, from gender studies focused on rural development, is concerned with understanding the social and health conditions of Indigenous women who protect the biodiversity of native corn and with it their own cultures, in contexts of neoliberal policies that constantly threaten their food systems and that have made their work invisible22.

Social context of Matlatzinca ethnic group in Mexico

Inequalities and inequity in health are accentuated in the Indigenous population in Mexico and have been associated with factors such as labor conditions, income inequality and belonging to vulnerable groups23-29. Therefore, there is a need to analyze health services to improve equity in the provision of infrastructure and human resources to promote better accessibility, utilization, and technical and interpersonal quality, especially in primary healthcare services30.

In Mexico, 11% of the population belongs to one of 68 ethnic groups, of which 52% are women. Five of these groups live in the State of Mexico: Nahua, Mazahua, Otomíes, Tlahuicas and Matlatzincas. The Matlatzinca ethnic group has suffered the greatest disintegration from the time of the Spanish Conquest (1536) to the present, being reduced to a single community: the San Francisco Oxtotilpan, with a total Indigenous population of 1076. The community is essentially agricultural and, because of marginalization, has high levels of poverty31. To supplement household income, men and young women migrate to nearby cities to join the salaried labor market under precarious and socially insecure conditions. In this context, older women are left to take care of the family and the means of peasant production and so are the target population of many social programs. For health care, they go to traditional healers or doctors at the local health center provided by the government. Each family is a beneficiary of medical services and public assistance programs; hence, women commit with high participation rates to the development of activities that benefit their health32. Although Indigenous women are the main participants in health and social programs, they are considered highly vulnerable because they subsist under conditions of poverty and food insecurity33,34.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was carried out on 93 Matlatzinca women from a rural area in central Mexico, with social characteristics such as community identity, adherence to traditions, and representativeness of Mexican ethnic groups. The area is recognized for its significance in the domestication and current production of corn. The participation of women in this community is essential for family, social and economic dynamics. It is a highly vulnerable community. Women in the study were selected by snowball sampling35 from February 2016 to April 2017. This sampling method was selected because resources for sampling were limited; however, the Indigenous women were able to participate because this method of CVR identification does not involve serum markers. This is useful in rural Indigenous communities with little access, when there is an open and massive call for participation in specific studies such as health diagnostics36. In this study, participation was obtained from women who responded to a call at the local health center.

All the women who participated in this study attended the community health center to register the variables; direct face-to-face interviews were also carried out. Women of this Indigenous population essentially are in charge of family health care and manage the economic income; therefore, they characterize the organized social response.

Data collection

Sociodemographic variables: The following information was obtained through direct interview: age, occupation (the primary activity of this Indigenous population is agriculture; given that the women are simultaneously engaged in activities related to gender and matriarchal roles, home and agricultural activity was considered as one occupational category, which included additional activities that involved the use of family care time within the home and essentially without economic remuneration), marital status (regardless of civilian status), number of children, monthly household income (in Mexican pesos (MEX$), according to the average exchange rate from February 2016 to April 2017 of MEX$19.05 per US$1), the presence of family history of chronic disease (such as diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypertension, renal disease, with previous medical diagnosis), the practice of any physical activity, and the consumption of alcoholic beverages and tobacco.

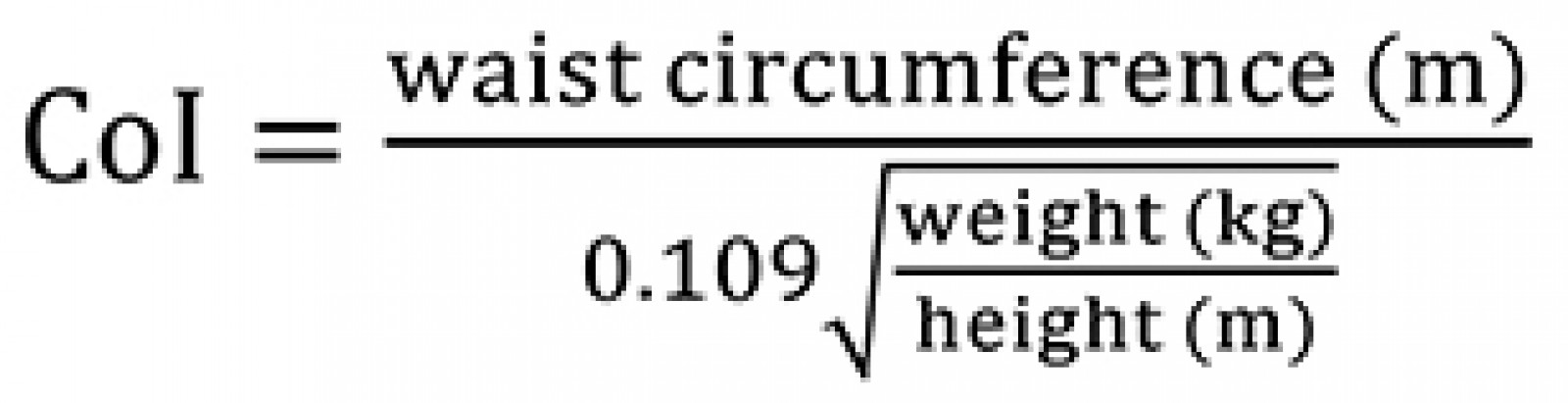

Anthropometric variables: Weight, height and WC measurements were carried out by the same trained personnel. Weight (kg) was measured with an electronic TANITA UM-061 scale, 100 g precision; the woman wore as few clothes as possible and no shoes, and stood in the center of the scale with her weight evenly distributed through both feet. Height (cm) was measured with a portable TANITA HR-200 stadiometer, 0.1 cm precision; the woman wore no shoes, and stood feet together, and heels, glutei and the upper part of her back in contact with the scale, both arms hanging down next to her body, and her head kept in the Frankfurt plane. WC (cm) was measured with a Gulick fiberglass retractable anthropometric tape with a length capacity of 0–150 cm by identifying the middle point between the inferior costal facet (tenth rib) and the iliac crests at mid-auxiliary line; the woman stood with her arms folded across her chest and with her weight evenly distributed through both feet. The weight–height ratio (WHI) was obtained by dividing WC (cm) by height (cm), and the conicity index (CoI) was calculated from the formula proposed by Valdez37:

Lipid serum concentrations: A blood sample was obtained from every participants, with 12-hour fasting. The sample was drawn through antecubital venipuncture using a BDVacutainer 6 mL tube for saline solution with coagulation activator to measure total cholesterol (TC), LDL-cholesterol (LDL-c) and HDL-cholesterol (HDL-c) concentrations, by the enzymatic colorimetric method38. The classification of dyslipidemias was made using the cut-off points of NOM-037-SSA2-2012, for prevention, management and control of dyslipidemias39, defining elevated concentrations of TC as >200 mg/dL and low HDL-c as <40 mg/dL.

Blood pressure: A calibrated HomecareDMH2000 aneroid sphygmomanometer was used to measure systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure with the participant sitting with her left arm, uncovered and bent, on a flat surface, at heart girth, after 5 minutes of rest; the average of two measurements was registered40. Following the Official Mexican Standard procedures and diagnosis criteria (NOM-030-SSA2-2009), for the prevention, management and control of arterial hypertension41, elevated systolic and diastolic blood pressures were defined as when the average values were ≥130 and ≥85 mmHg respectively.

Framingham risk score: The FRS42 was calculated by considering age, sex, diabetes mellitus diagnosis, TC, HDL-c concentrations, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and tobacco consumption. Each participant was classified according to the percentage of risk as low risk <10%, moderate risk 10–20% and high risk >20%. For this analysis, the moderate risk and high risk categories were grouped into a single category called ‘with risk’, and the risk percentage of <10% was categorized as ‘no risk’.

Statistical analysis: Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or percentage as appropriate. Median, maximum, minimum and 95%CI were used in variables such as number of children, monthly income, height, WC, CoI, WHI, TC and HDL-c.

ROC curves were analyzed to evaluate which of WC, CoI and WHI was the best at predicting CVR. The identification of the cut-off points with a balance between sensitivity and specificity was made based on the calculation of the maximum Youden index (sensitivity + specificity – 1). The FRS was considered the gold standard for the area under the curve (AUC) and the 95%CI for each of the anthropometric indexes. Briefly, ROC curves were analyzed to assess whether anthropometric measures were predictors of CVR. First, the means of the continuous values of sensitivity and specificity for each anthropometric indicator were tabulated. Subsequently, the ROC curve graph was used, where the true positive rate (sensitivity) was on the y-axis and the specificity (false positive rate) was on the x-axis. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA v14.2 (stata.com; STATACorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA).

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Research of the Medicine School of the Autonomous University of State of Mexico (Register number 15CEI03420140313), and all the procedures according to the Declaration of Helsinki were followed43.

Results

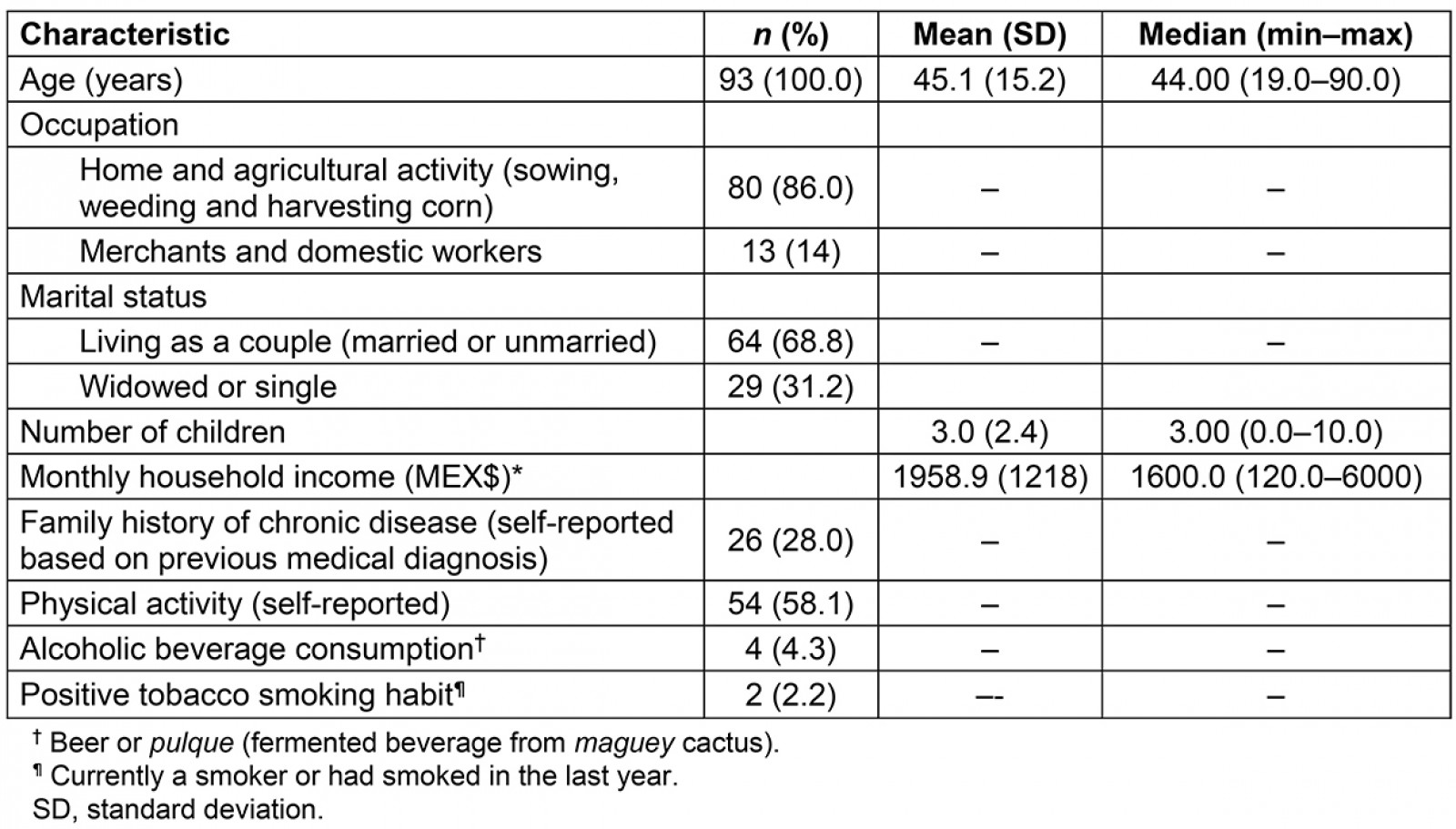

The response rate of the study population was 93%. Table 1 shows the population’s sociodemographic information. The mean age was 45.1±15.2 years, being a homemaker and doing agricultural activities for a living was the prevalent activity (86%), 68.8% lived with partners, and the median number of children was 3 (0–10).

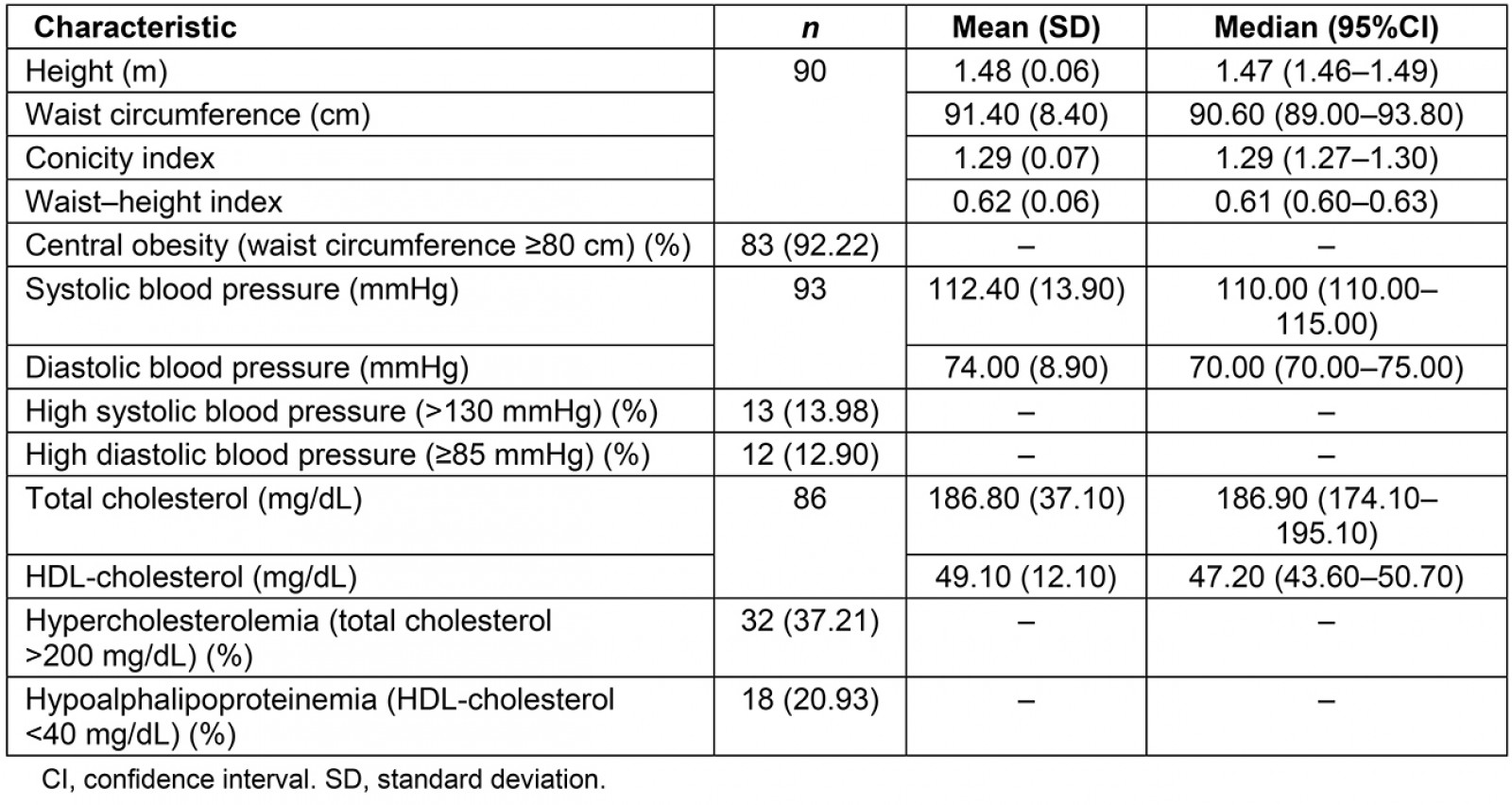

The mean monthly income was MEX$1958.9±1218, equivalent to US$102.8 (taking into account the average exchange rate between February 2016 and April 2017 of MEX$19.05 per US$1). A total of 28% of participants reported a relevant medical history, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, renal disease and cancer. The practice of physical activity (walking or cycling) was self-reported by 58.1% of the women. The consumption of alcoholic beverages and tobacco was 4.3% and 2.2% respectively. Mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures were 112.4±13.9 and 74.0±8.9 mmHg respectively (Table 2). Mean TC was 186.8±37.1 mg/dL and HDL-cholesterol was 49.1±12.1 mg/dL.

Since the mean height was 1.48±0.06 m, the population was considered to be of low height according to the guidelines of Official Mexican Standard (NOM-008-SSA-2017), for the management of overweight and obesity (low height: under 1.50 m) (Table 2)44.

A worrying find was the high prevalence of central obesity in 92.2% of the women, while 14.0% presented elevated systolic blood pressure, 12.9% presented elevated diastolic blood pressure, and 37.2% and 20.9% showed hypercholesterolemia and hypoalphalipoproteinemia respectively.

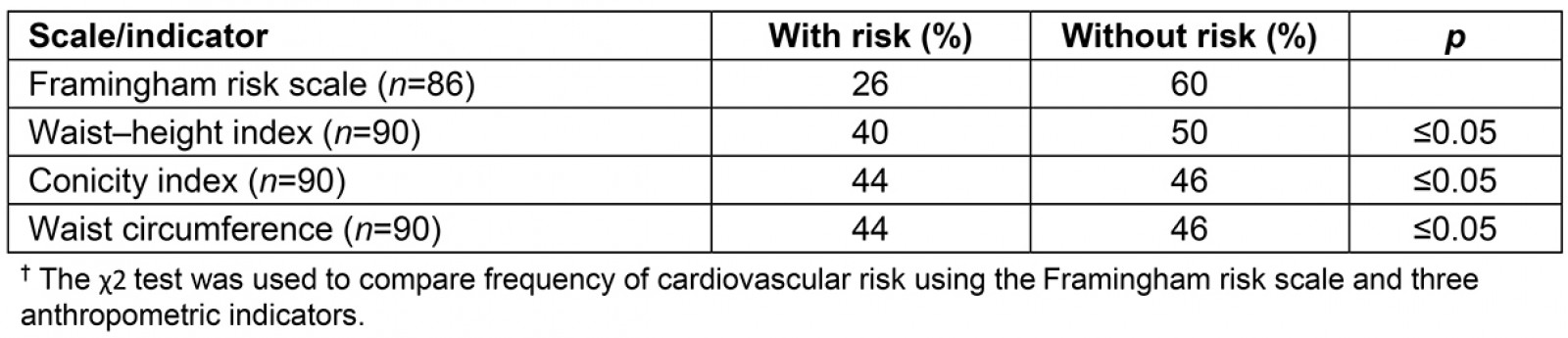

Table 3 shows statistically meaningful differences between the frequency of the presence of CVR, based on the FRS. Specifically, for this study, FRS was categorized as no risk <10% and at risk ≥10%, to compare the presence of CVR among the other indicators. FRS, WHI, CoI and WC predicted 30.2%, 44.4% and 48.9% respectively of the women at CVR.

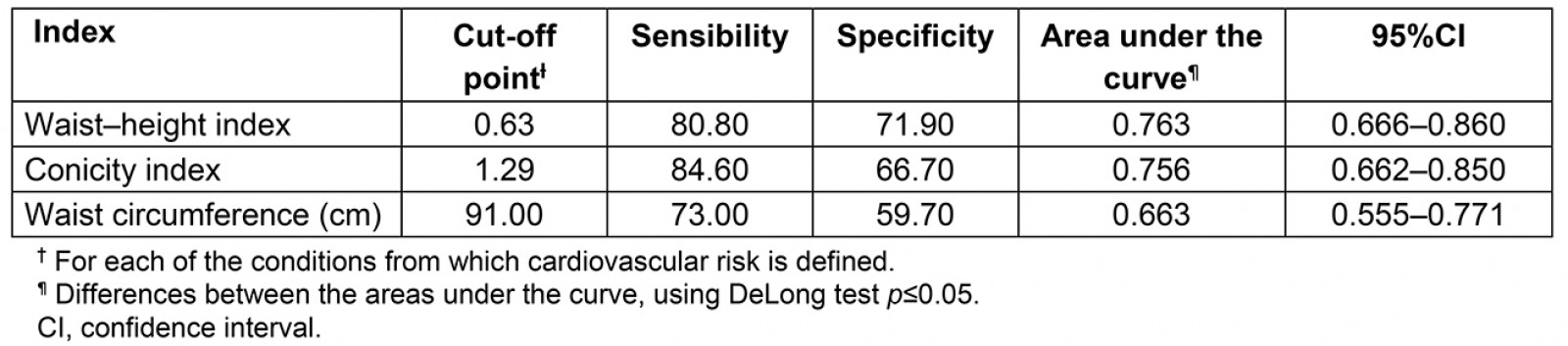

Table 4 shows the cut-off points suggested with balance between sensitivity and specificity and the AUC of the three anthropometric indexes with their confidence intervals.

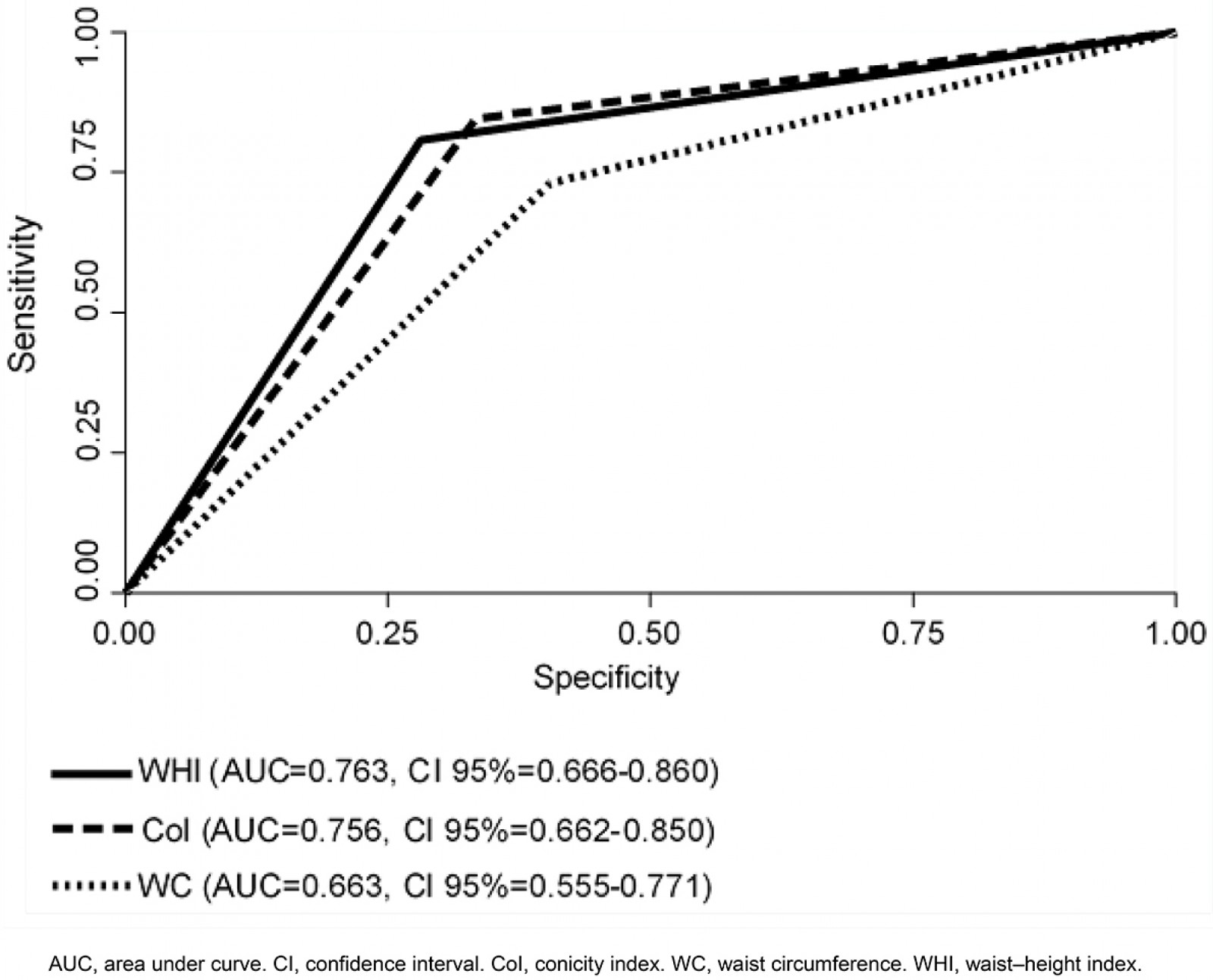

On comparing the predictive capacity of the three indexes (WHI, CoI and WC) to the FRS, the three anthropometric indexes were found to have shown sufficient capacity to predict CVR. WHI showed the greatest predictive capacity with AUC=0.762 (95%CI 0.666–0.860). Regarding the DeLong test45, statistically meaningful differences were found among the AUC of the three indexes (p≤0.05), and, in conclusion, the AUC of WHI was the greatest.

Figure 1 shows ROC curves of the three proposed indexes. The ability for each index to predict CVR is given by the AUC compared with the FRS. In this study, WHI showed the greatest AUC (0.763, 95%CI 0.666–0.860), demonstrating a CVR predictive power of 76.3% compared to FRS.

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of 93 Matlatzinca women

Table 2: Anthropometric variables, blood pressure and serum lipid concentrations of 93 Matlatzinca women

Table 3: Comparison of risk prevalence for cardiovascular disease using Framingham risk scale and three anthropometric indicators

Table 4: Cut-off points, means of sensitivity, specificity and areas under the curve of anthropometric indicators for cardiovascular risk prediction with respect to the Framingham risk scale

Figure 1: The area under the curve through receiver operating characteristic curves of waist circumference, conicity index and waist–height index.

Figure 1: The area under the curve through receiver operating characteristic curves of waist circumference, conicity index and waist–height index.

Discussion

There are few comparative studies of anthropometric indexes that use ROC curves to predict CVR in Mexico, particularly in Indigenous groups of women living in rural areas. The authors also do not know of any similar research specifically carried out in Indigenous rural women living under vulnerable social and economic conditions, in which the resources for biochemical testing are lacking.

Although WC continues to be recommended as a measurement in clinical practice because it offers additional information for predicting morbidity and mortality, it has been criticized because its exclusive use for predicting CVR in Hispanic/Latino adults underestimates the prevalence of metabolic syndrome46.

Three indexes proposed by different European and Asian authors were analyzed in this study47,48. However, the characteristics of specific regions must be considered, as established by the International Diabetes Federation49.

This research shows cut-off points with balance between sensitivity and specificity for WC, CoI and WHI for Indigenous Mexican women; this suggests the use of anthropometric measurements in primary health care for identifying CVR in low-income populations, which will limit the dependency on biochemical tests.

The three indexes showed enough CVR predictive capacity compared to FRS. However, WHI had the greatest AUC (0.763).

These results are similar to those of Vidal Martins et al for 349 older adults17. These authors evaluated, using ROC curves, the capacity of six anthropometric indexes to discriminate CVR: medial point between the last rib and the iliac crest, minimal WC, umbilical circumference, BMI, WHI and CoI. They identified that those anthropometric indexes showed enough CVR predictive capacity, and, specifically in women, minimal WC and WHI presented the greatest AUC (0.70), with cut-off points of 84 cm and 0.63 respectively. In the present study, WHI also had the greatest AUC (0.763), with the same cut-off point of 0.63.

Metabolic syndrome has been established as a precursor of CVR. Mora-García et al50, in a study of 423 Colombian women, calculated cut-off points with balance between sensitivity and specificity to diagnose metabolic syndrome. WHI showed greater AUC (0.742) (95%CI 0.683–0.801) and cut-off points of 0.56. In this study, AUC and CoI are similar to those in Mora-García. However, the cut-off point is higher than that reported in Colombian women (0.07). Although height was not included in the abovementioned study, other studies show that this measurement adjusts the values of WC, indicating the distribution of fat and body mass. In addition to this, people with low height more frequently present morphologic alterations in the venous system51,52.

Chen et al47 assessed BMI, WC and WHI to predict arterial hypertension in 9905 adults in a rural Chinese community, reporting that WHI was the best arterial hypertension predictor in women, with no disregard to the fact that all the anthropometric indicators had an adequate power of discrimination (AUC>0.6).

Similarly, in this study the three indexes that were evaluated in Matlatzinca Indigenous women showed enough power of discrimination, WHI being the best CVR predictor. The difference observed was that cut-off points were higher (WC 91, CoI 1.29 and WHI 0.63) than for women from China.

Even though this study and Chen’s study were both carried out in rural communities, the differences may be explained by racial or ethnic characteristics, as well as the sociodemographic conditions in each region53.

WC is one of the most widely used anthropometric indicators for diagnosing central obesity, which is considered as a CVR factor. In this study, WC showed the lowest AUC (0.633) (cut-off point 91 cm, sensitivity 73.0, specificity 59.7). In contrast, in the study of Abulmeaty et al54, in which they assessed the predictive capacity of 12 anthropometric indicators in 390 men and women, WC showed AUC=0.752 (cut-off point 88.5 cm, sensitivity 66.7, specificity 71.2) and it was one of the best CVR predictors.

Despite the criticisms of the use of WC, while WHI is suggested because it includes height, CoI relates weight, height and WC, considering them as better predictors of hypertension, metabolic syndrome and CVR55.

Limitations

The study had the following limitations: data acquisition was retrospective; only women were included, the analysis being derived from a project with their specific participation; there was no analysis of serum samples to verify the estimation of CVR; self-reported data were used about previous diagnoses of diabetes mellitus, which is an important bias, essentially because a large number of people living with diabetes do not know it; and no data were collected on qualitative aspects of women’s interest in, desire for, and acceptance of CVR identification by anthropometric indicators.

Finally, statistical analysis using ROC curves has a main limitation, which is the use of dichotomous diagnostic criteria (with or without risk), by categorizing continuous outcomes such as weight, height and anthropometric indices analyzed. In view of this, discrete categorization of the data has been used in this analysis, mitigating this limitation.

Conclusion

WHI, CoI and WC showed enough capacity to predict CVR in these Indigenous Mexican women. WHI had the highest power of prediction and balance between sensitivity and specificity in this population.

The clinical use of anthropometric indexes is sufficient to identify CVR in the early stages. The use of WHI in primary health services, especially in rural and Indigenous populations with severely limited resources for health care, is proposed to reduce health gaps in order to improve equity in access to health care.

With this evidence, the Matlatzinca community will benefit by improved access to health care through the identification of CVR without the need to use serum markers only. In addition, existing resources in the rural health system will be optimized.

Acknowledgements

This study derives from the research project ‘Mesoamerican maize and its scenarios for rural development’, National Council of Science and Technology CB 2009/130947.

References

You might also be interested in:

2007 - Skill shortages in health: innovative solutions using vocational education and training