Introduction

The World Federation of Occupational Therapy (WFOT) defines occupations as ‘everyday activities that people do as individuals, as a family, and with communities, to occupy time and bring meaning and purpose to life. Occupations include things people need to, want to, and are expected to do’1. Through engagement in occupations, people can develop their physical, psychological, social and spiritual abilities. Participation in occupations and the meaning derived from them contributes towards the development of a person’s identity and self-efficacy2. Occupational therapy is a health science profession concerned with enabling people, individually or as groups, to engage in meaningful activities. The principal goal of occupational therapy is to promote health and the quality of life through participation in activities or occupations2.

Adolescents require opportunities to engage in occupations and need to have the opportunity to choose the occupations they want or need to engage in3. In Lesotho, an adolescent is described as being aged between 10 and 19 years4. Occupational choice describes the process and factors that influence a person’s capability to engage in occupations5. The individual, and their perception of whether they have an internal or external locus of control, influence occupational choice5,6. Moreover, occupational choice is influenced by the environmental, cultural and economic context6. Research about adolescence and occupational choices has primarily focused on engagement in risky health behaviours7-9. The occupational choices and behaviours of adolescents are often indicators of their future life progression10. Subsequently, it is essential to intervene when adolescents make choices that may have negative lifetime repercussions on their health and life trajectories11.

Occupational therapists are concerned with promoting health through facilitating participation in occupations12. Despite the acknowledgment that engagement in occupations could empower adolescents and have positive ripples in their health5, there is little understanding of the different occupations that adolescents living in disadvantaged communities engage in13. A deeper understanding of adolescents’ occupational choices, the motivation underlying the choices and the factors that influence participation would assist with guiding intervention practices for health promotion and disease prevention programs.

Adolescents make up 20% of the population of Lesotho and experience high rates of abortion and teenage pregnancy, HIV transmission and mental health issues14-16. It is crucial to know adolescents’ occupational choices to ascertain which behaviours contribute to their risky behaviours and mental distress. In Pitseng, located in the Leribe district (1 or 10 districts of Lesotho), there is a lack of information on adolescents’ occupational choices and a paucity of information on the motivation underpinning their occupational engagement in this semi-rural context. The link between the adolescents’ church and their villages was explored as part of the mesosystem. The cultural values, beliefs, traditions, customs and laws governing the Pitseng community in which the adolescent resides were explored as part of the exosystem17. This study sought to explore the occupations that school-going adolescents of Pitseng engaged in to gain insight into their behaviour and strategies needed to develop sustainable health promotion and prevention programs for adolescents.

Methods

Study design

A descriptive explorative qualitative design was used in the study. This design allowed the participants to share their experiences and perceptions around engaging in occupations and the meaning underlying the occupations. A qualitative design was chosen as there is little known on the phenomena being studied. The semi-structured focus group interviews were used to explore and understand the adolescents’ lived experiences of the occupations they engaged in18.

Study location

The study was conducted in Pitseng, Leribe district, Lesotho, which has a population of 18 948 people19. Pitseng is a semi-rural community council that lies at the foothills of the Maluti Mountains. It is a low-income area with poor infrastructure20, whereby the inhabitants survive from subsistence farming, mainly rearing animals and planting crops. The subsistence agriculture in the Leribe district accounts for 22.7% of the total subsistence agriculture in Lesotho21, and 61.2% of the population in this area lives below the national poverty line22. There are four high schools in the area of Pitseng.

Study population and sampling strategy

Purposive sampling was used to obtain a diverse range of participants relevant to the study’s objectives23. School-going adolescent participants aged 13–15 years and in grades 8–10 were sought at three different high schools within the Pitseng area. All participants had to reside in Pitseng. The selection of the three high schools ensured that both rural and peri-urban perspectives were attained. School 1 is located in a peri-urban area near a shopping complex and a taxi rank. Schools 2 and 3 are located on the foothills of the mountains in areas classified as rural. Schools 1 and 3 enrol learners from grades 8–12, whereas school 2 enrols learners from grades 8–10 only.

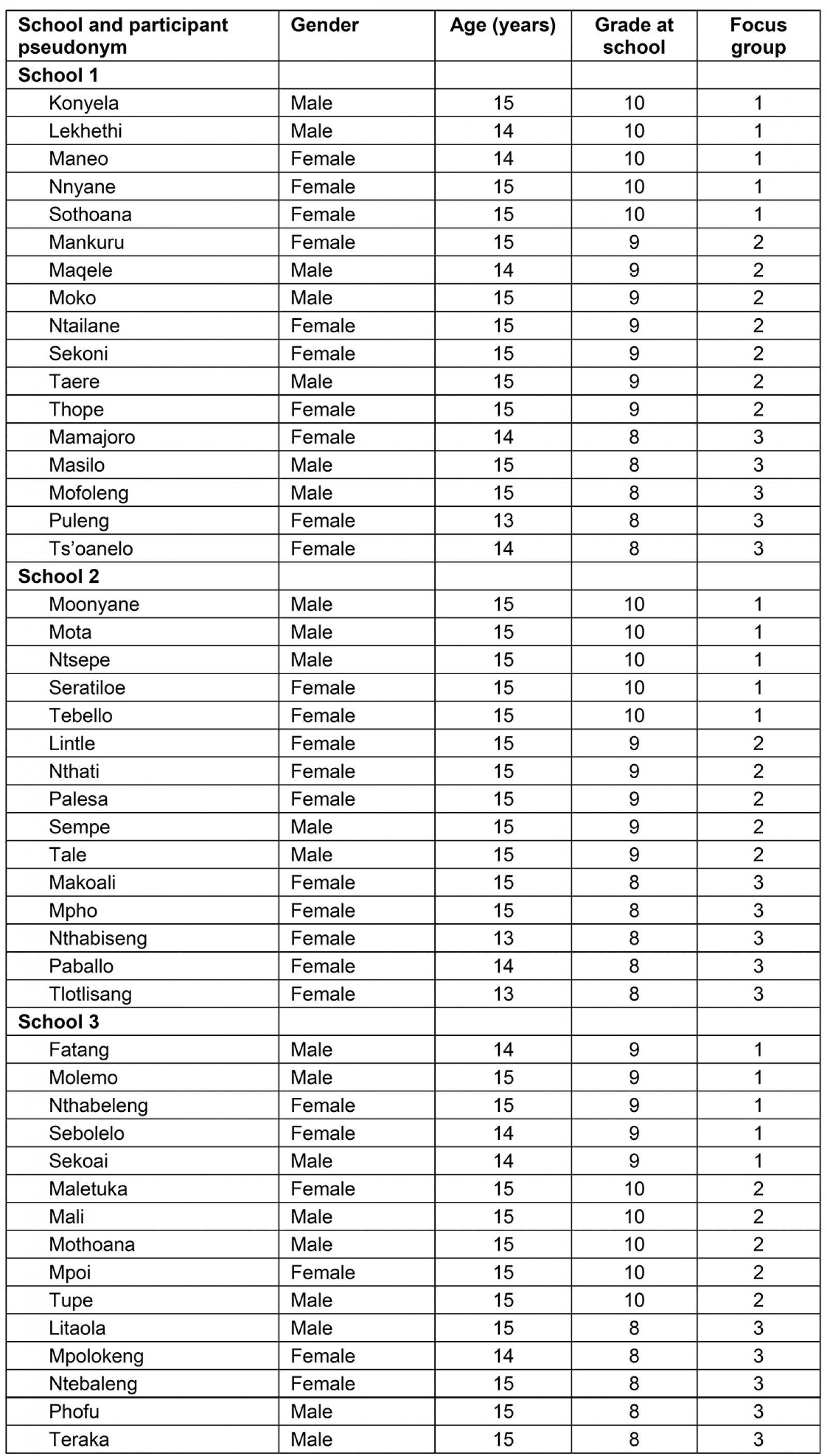

Adolescents who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were given information sheets and consent forms for their parents to read and sign. Participants signed assent forms before commencing the focus group interviews. There were 47 participants in the study, of whom 26 were females and 21 were males.

Data collection

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory was used as a theoretical lens to guide the study. The data collection explored the personal factors, interpersonal relations, social roles, responsibilities and activities with which each adolescent has direct contact in their immediate surroundings and their family structure, school, church and village context as part of the microsystem. Information sheets and consent and assent forms for parents and learners, respectively, were all translated to Sesotho as this was the participants’ home language. Nine focus group interviews were conducted in total, with three focus groups per school. Eight focus groups consisted of five learners each, and one focus group had seven learners. The participants in each focus group were from the same grade. The homogenous focus group interviews allowed the adolescents to share their experiences more freely as they were amongst peers18. All focus group discussions were 45–90 minutes in duration and were audio-recorded with permission. The primary researcher conducted the focus group interviews. English and Sesotho were spoken interchangeably, in accordance with the language preferences of the participants. The primary researcher grew up in Pitseng and was therefore familiar with the study location. This allowed for an insider or emic view, which facilitated the adolescents feeling free to share their experiences18. The primary researcher wrote a reflective statement before commencing data collection, to prevent her from imposing her views during the data collection and analysis.

Data analysis

The audio-recordings from all the focus groups were transcribed verbatim. The sections in Sesotho were translated to English, and back-translated into Sesotho to ensure the veracity of the transcription. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data. Thematic analysis emphasises classifiable themes and patterns of living and behaviour24. The following steps formed part of the data analysis process. The primary researcher familiarised herself with the data, through reading and re-reading the transcripts while making notes in the margins. This was followed by generating the initial codes, searching for themes and subthemes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and finally producing the thematic map and journal article24. The primary researcher discussed the initial codes and grouping of subthemes and themes with the other researchers to gain consensus and reduce potential bias.

Informed consent and permission to audio-record the focus group interviews were obtained from the participants’ parents or legal guardians as the adolescents were minors. Participants signed assent forms for participation and audio-recording. Confidentiality was maintained throughout the study through the use of pseudonyms. Participation was voluntary, and the participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any stage of the study.

Ethics approval

Ethics clearance was granted by the Human and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu Natal (HSS/0410/019M). In addition, ethics clearance was sought from the Lesotho Ministry of Health Research and Ethics Committee (ID211-2019). Gatekeeper permission was obtained from the Lesotho Ministry of Education through their Leribe district education and training office and from the principals of the schools that were part of the study.

Results

Demographics of participants

The participants’ ages ranged between 13 years and 15 years, with the majority of participants aged 15 years. The demographics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Characteristics of participants from three schools in study

Themes of study

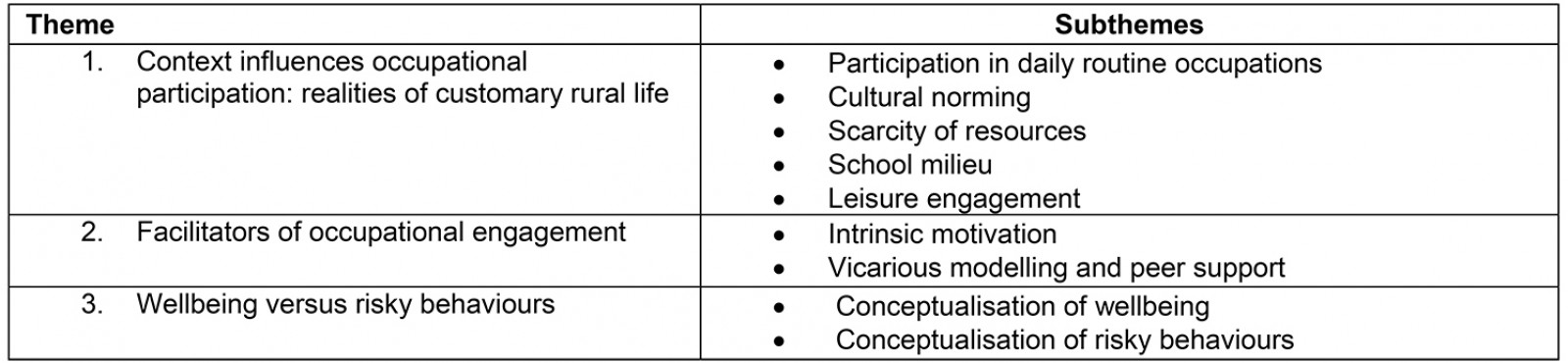

Three main themes emerged from the study. The themes and their corresponding subthemes are highlighted in Table 2.

Table 2: Themes and subthemes of study

1. Context influences occupational participation: realities of customary rural life

The participants emphasised that the context that they lived in shaped their engagement in daily occupations. This was woven through the subthemes of participation in daily routine occupations, cultural norming, scarcity of resources, school milieu and leisure engagement.

Participation in daily routine occupations: The participants reported that they had to boil water for bathing in the mornings, which delayed their departure for school. In addition, there were no stoves at home, which necessitated the use of primus stoves for cooking, and heating up a metal iron for ironing, which prolonged the completion of these tasks. Pitseng is a low socioeconomic area, and participants indicated there were times when there was not enough food in their homes, which highlighted food insecurity. The participants voiced that they redirected their attention towards play and socialisation with friends to avoid focusing on their hunger.

The fact that we live in an area that has no electricity affects what we do, or don’t do … because for example, we light up a primus stove to boil water … we wait so long for the water to be heated up. (Tebello, female, age 15, focus group 3, school 2)

I wash the dishes from the previous night and mop the floor. (Seratiloe, female, age 15, focus group 1, school 2)

The reason why we play when we have gone to the stream while drying our clothes in the sun is that we don’t feel hungry easily … but when we are at home, or close to home, we feel like eating almost every time … so sometimes there is not enough food. (Fatang, male, age 14, focus group 1, school 3)

The participants reported that they were expected to clean the interior of the home and cook for the family, both during the week and on the weekends. Additional home chores included drawing water from the well, cleaning the outside of their homes and surroundings, gardening and subsistence agriculture, planting crops and caring for livestock, and taking care of their siblings. The participants highlighted that balancing school and home workload caused fatigue, which inhibited them from studying in the evenings on weekdays.

After milking the cows, I go and check on the crops to see what needs to be done for them to grow well. (Mota, male, age 15, focus group 1, school 2)

I feel really tired to study in the evenings, because I have to cook and wash my uniform, on top of having been in school the whole day. (Mamajoro, female, age 14, focus group 3, school 1)

After eating, I wash my uniform and my younger brother’s uniform as well. (Puleng, female, age 13, focus group 3, school 1)

Cultural norming: Participants reported that females were expected to do housework, whereas the males were expected to look after the livestock, as per the cultural mores. The participants were expected to abide by the sociocultural norms in their home context.

I am expected to cook and clean the whole house at home. I even wish I had a big sister who would be responsible for doing all the house chores on my behalf. (Ntebaleng, female, age 15, focus group 1, school 3)

On Saturday, I wake up at 6 am and milk the cows. After that, I eat and then take all our animals out to graze in the pastures away from the village. My parents expect me to do these things every weekend and on school holidays. (Sempe, male, age 15, focus group 2, school 2)

Scarcity of resources: Scarce resources, few opportunities and a lack of infrastructure contributed immensely to decreased engagement in activities. For example, the lack of soccer boots prevented participants from playing soccer. The lack of electricity in the adolescents’ homes limited school-related activities in the evenings.

Some participants who aspired to be entrepreneurs reported the lack of capital as a limiting factor. They could not sell snacks at school or vegetables in the marketplace on the weekends.

There was no community library in the central area of Pitseng. The one library established by Help Lesotho, a non-government organisation, is difficult to access due to limited public transport. The lack of equipment for fitness training in the community gyms or karate at home limited the participants’ ability to engage in fitness training activities. The lack of a park with different games or areas for relaxation was seen as an obstacle to the participants’ ability to socialise and relax in a conducive environment.

So even on days when I decide to go to the field to play, another problem becomes not having soccer boots. (Fatang, male, age 14, focus group 1, school 3)

We are being taught about business during accounting and business studies, and I would like to implement that knowledge as early as now; however, my parents cannot afford to give me startup capital. (Maletuka, female, age 15, focus group 2, school 3)

I would like to read more because reading is my number 1 hobby, especially novels during school holidays. So, for now, I am being restricted by the fact that there is no library (Nthabiseng, female, age 13, focus group 3, school 2).

School milieu: Participants across the three schools were expected to attend school from Monday to Friday, 7 am to 4 pm. Moreover, there was a compulsory Sunday study period from 9 am to 11 am for all participants. Grade 10 participants also had to attend school on Saturdays to copy notes, as instructed by their teachers. Participants reported that excessive noise at school was a barrier to their learning. They resorted to going to school early to use the quiet environment to study before the other learners arrived.

During study time in the morning, sometimes it is hard to concentrate as there is a lot of noise. I, therefore, get to school early so that I can study while my mind is still fresh, and before other students arrive with their noise and distractions. (Sebolelo, female, age 14, focus group 1, school 3)

Leisure engagement: The male participants played soccer almost daily as they had informal soccer fields in all the villages. Some of the female participants also engaged in women’s’ soccer matches and practice. However, they did not practice every day because of their responsibility for house chores and cooking after school. Furthermore, participants reported that watching soccer matches between the bigger community teams on the weekends was one of their preferred activities.

I have joined a ladies’ soccer team in our village. We practice twice during the week in the evenings, but our matches are on Saturdays or Sundays. (Mpolokeng, female, age 14, focus group 3, school 3)

If that Saturday there is a football match at the field, I go to watch it until 6 pm. (Konyela, male, age 15, focus group 1, school 1)

The participants also played games such as morabaraba, a strategy game similar to checkers or chess using stones or wooden pieces; card games; and liketo, a game where a hole is dug in the ground, and the players use stones to compete against each other through counting. Also, they played mokou, which is a hit-and-chase game that involves two groups of players competing against each other. Further games included skipping rope, stick fights, phone games and pool/snooker. Other leisure activities that participants engaged in included exercise and jogging, karate, taekwondo, watching television and using social media. Socialising with friends, taking leisure walks, meeting their girlfriends or boyfriends and socialising as couples were also reported. Dancing and listening to music, playing netball, reading novels and playing video games were other meaningful leisure activities that the participants engaged in.

After completing writing the notes, I go home, eat, leave my notebooks, then I go to play pool. (Konyela, male, age 15, focus group 1, school 1)

We play card games, or my friends and I just sit and chat. (Nthati, female, age 15, focus group 2, school 2)

I like training and building up my body. I get inspired when I see bodybuilders. I can only do exercises which require no equipment. (Sekoai, male, age 14, focus group 1, school 3)

I like dancing so much. (Palesa, female, age 15, focus group 2, school 2)

2. Facilitators of occupational engagement

The participants emphasised that there were factors that facilitated them to engage in occupations, namely their intrinsic motivation, and vicarious modelling and peer support.

Intrinsic motivation: The participants were motivated to get up early to study. They were also enthusiastic to engage voluntarily in group discussions and revisions after school. Other participants were eager to attend church services both on Saturdays and Sundays. Moreover, participants reported not engaging in leisure activities because they wanted to focus more on their academic work, as they had future hopes of alleviating poverty in their homes.

I wake up in the morning at 02:30 am and study until 4:30 am. (Maneo, female, age 14, focus group 1, school 1)

… at 11 am I am ready to go to the 12 pm youth church service, whereby we clean the church for Sunday service … after cleaning, there will be teaching, bible study and encouraging each other as the youth, regarding the challenges that we face in life … (Tupe, male, age 15, focus group 2, school 3)

The reason why I don’t usually go out of our house to play is because I like to focus more on my schoolwork. I want to be successful in my schoolwork, and assist my family in getting out of poverty. (Mpho, female, age 15, focus group 3, school 2)

Vicarious modelling and peer support: Participants reported vicarious modelling of their elder siblings, which implicitly prepared them for the roles and tasks at home. Moreover, participants viewed high-performing students as an inspiration and modelled their study behaviours on these students’ habits.

I just saw my elder sister doing all the housework when I was growing up, and then I followed in her footsteps. (Nnyane, female, age 15, focus group 1, school 1)

We engage in group discussions because we realised that other Form E or grade 12 students who went before us used to engage in them, and they passed very well. (Ntailane, female, age 15, focus group 2, school 1)

3. Wellbeing versus risky behaviours

Under this theme, a comparison of how the participants perceived wellbeing and risky behaviours was explored.

Conceptualisation of wellbeing: Participants perceived wellbeing as experiencing health in totality. They regarded wellbeing as having their material and basic needs met by parents or guardians, financial and emotional support from their parents, and eating a balanced diet. Moreover, participants reported that being active, fit and able to exercise played a significant role in their wellbeing. Many of the participants’ perceived wellbeing as living a happy and satisfying life. Some participants viewed wellbeing as a state where their human rights were being met, in terms of their emotional, spiritual and physical health.

Well-being means being okay physically, mentally and emotionally … it is not just about being happy, but being healthy as well. (Maneo, female, age 14, focus group 1, school 1)

Well-being is about how a person thinks or acts in order to achieve success and attain their dreams. (Mali, male, age 15, focus group 2, school 3)

Conceptualisation of risky behaviours: The participants defined risky behaviours as having bad attitudes, or carrying out actions and habits that were perceived as unacceptable for children or the community. Participants stated that they engaged in risky behaviours in the absence of their parents or guardians and that peer pressure compelled them to engage in these behaviours. Participants noted that excessive time spent on one activity could lead to ill health due to neglecting other activities that uphold body functioning. Moreover, when the participants had money, they consumed alcohol and sniffed glue. Reasons that motivated the substance use were attributed to using substances as a mood elevator, to escape reality and to feel more confident or experience pleasure.

It can be doing something excessively; for example, I play games and watch movies a lot. That is being unhealthy because one may end up having some health issues like being ill from not exercising your body. (Lekhethi, male, age 14, focus group 1, school 1)

When you sniff glue or get drunk after drinking alcohol, it feels good. It is as if life only has good moments. You forget about everything bad that may be happening, or that has happened in the past. (Paballo, female, age 14, focus group 3, school 2)

Disappearing from home without parental consent, fighting when intoxicated, performing masturbation, watching pornography, and having multiple partners or unprotected sex were other risky behaviours reported by the adolescents. The participants reported other undesirable behaviours, which included defiant behaviour, such as talking back to their parents, being irritable, and lying or refusing to carry out the instructions of teachers, parents or guardians.

I sometimes fight when I have been offended by something a person said or did to me. (Tale, male, age 15, focus group 2, school 2)

Another thing that I did was that I fell in love with many boys at the same time … for example, there was a time when I had four boyfriends at the same time ... (Paballo, female, age 14, focus group 3, school 2)

I got home very late sometimes … at like 9 pm, or I even waited for my family to fall asleep, and then I snuck out and went to a party, or to drink alcohol at the bars with my friends. I would put my clothes and a pillow under the blankets … in case my parents went into my room before I got back. (Konyela, male, age 15, focus group 1, school 1)

Discussion

This study set out to gain an in-depth understanding of the occupations that school-going adolescents in Pitseng engaged in and the factors that facilitated or hindered their occupational engagement. The impoverished rural context negatively influenced the participants’ engagement and choice of occupations.

Daily routine occupations took longer to complete and were more arduous due to the impoverished rural context. The lack of amenities such as electricity compelled the participants to rise earlier than they would have preferred, to allow time for heating water on a fire for bathing before school, and heating a metal iron to press their clothes. Many of Lesotho’s residents have to fetch water from a well22,25. The lack of electricity in the adolescents’ homes limited school-related occupational engagement in the evenings. Electricity connections have been increasing over time and, by 2019, 39% of Lesotho’s 537 000 households were connected to the grid. However, the mountainous terrain and remoteness of some rural settlements necessitate high grid extension costs and, consequently, only around 14% of rural households have access to electricity25.

The participants were expected to complete household chores and care for siblings before leaving for school. The participants often used engagement in socialisation activities after school hours to distract themselves from hunger due to a lack of food security, which was prevalent in the area26. Food insecurity, together with poverty and unemployment, are acknowledged as problems in Lesotho26. Previous research concurred that the burden of household chores and responsibilities placed on adolescents living in underprivileged rural communities decreased their time to engage in school and other leisure activities27.

The traditional cultural norms of Pitseng, or defiance thereof, directed most of the participants’ occupational choices. The traditional cultural mores shaped gender roles. Girls were expected to do household chores, whereas boys were expected to engage in subsistence farming and to take care of livestock25. This reflected cultural norming and has been observed in other African societies, including South Africa27. This finding was supported by research in rural Ethiopia that showed Hamar children were willing to continue with their intergenerational agropastoral life. In contrast, their urban peers were motivated by their Western schooling to reimagine their futures and find formal work28. The participants maintained the status quo by abiding to the sociocultural norms in their home contexts. Although there are similarities with South African youth, the agrarian lifestyle is practised on a larger scale in Lesotho due to the subsistence economy. Moreover, the researcher believes that Lesotho is a more traditional society, governed by a chieftaincy system, and has stricter cultural rules and regulations.

School and school-related activities were the dominant occupations in adolescents’ lives. Adolescents were expected to spend long durations in school, even on a Saturday, which leads to limited time available to spend on leisure or other occupations such as spirituality. This led to discontentment in some of the participants, as they felt deprived of meaningful activity. This finding correlates to other studies, which have shown that engagement in spiritual activities promotes life satisfaction in adolescents29,30. However, several adolescents considered academic success as a potential means of alleviating poverty for the adolescent and their family31,32. Entrepreneurship was taught as part of the curriculum as seen in this extract from The Lesotho Ministry of Education and Training Curriculum and Assessment Policy: ‘… the formulation of this Policy Framework is oriented towards approaches placing primacy on survival of a learner, not only in his/her daily school routine but also as a member of a broad community life, today and tomorrow, locally and globally’ (p. 4)33. Some adolescents wanted to implement the entrepreneurship skills taught in school but lacked start-up capital.

The adolescents valued peer learning as this was perceived as a method to master challenging subject content, thereby improving academic performance and school engagement. Peer learning facilitated the formation of a social network that allowed the learners to learn collaboratively and support each other. The value of peer learning is acknowledged34,35. Both individual and peer learning reinforced and stimulated cognitive development34,35.

The school setting supported learners by facilitating engagement in extracurricular activities, such as clubs and sporting activities, for all participants, even those who were adversely impacted by poverty. Engagement in organised extracurricular activities was perceived to promote wellbeing and it allowed the participants to thrive in their learning environments29,32,36.

Leisure interests and values of the adolescents revealed gendered differences. Male participants showed more interest in playing soccer than their female counterparts did, while female participants enjoyed socialisation and singing, a finding supported by the literature37,38. Soccer or football is the most widely played sport in Lesotho, and the best players play professionally in South Africa39. Judo, boxing, long-distance running and horseracing are other popular sports in Lesotho39. The adolescents in this study enjoyed shared mealtimes, which fortified their attachment with family members, and cemented the ‘togetherness’ of families. Similar findings were noted in a study on families, meals and synchronicity40.

Living in resource-constrained contexts meant fewer recreational facilities and choices for leisure engagement28,41. Consequently, adolescents engaged in leisure activities that were free and easily accessible in their natural environment41. The participants’ improvised by making items for play, like grass skipping rope and balls made of sand and plastic bags. This spurred their creativity as they had to use what was available. This creativity can extend to other areas of their lives and into adulthood. Moreover, soccer, jogging and other free activities were often chosen as leisure pursuits. Most participants engaged in more sedentary activities, such as using social media on their phones and playing video games. Excessive engagement in sedentary activities could increase the risk for lifestyle diseases, such as heart diseases, diabetes, hypertension and stroke42. Active and vigorous leisure pursuits were perceived to improve the participants’ engagement in scholarly occupations. Concentration has been shown to improve after engaging in physical activities43. Literature confirms that adolescents who engage in active leisure pursuits experienced lower depressive symptoms and showed a decreased preoccupation with their personal problems43-45.

This study highlighted that being intrinsically motivated facilitated participation in schoolwork, church deeds, and personal empowerment to improve their family’s socioeconomic status. The participants displayed strong intrinsic motivation towards scholastic pursuits, despite the long hours, as this was seen as a lifeline out of poverty. The resourceful participants created tools for sport and engaged in activities that did not require many resources, such as soccer. This aligns with the literature indicating that intrinsic motivation facilitates self-advocacy, goal achievement and positive self-esteem46.

Vicarious modelling by siblings, parents and guardians inducted the participants into the roles and occupations they had to perform at home. These inherited practices and norms shaped the adolescents’ life paths and limited the time available to engage in other occupations. For example, several boys did not perform as well or finish school, due to the expectation that they would engage in agrarian tasks after completing school. The study also revealed that female adolescents had less leisure time to use at their discretion due to the responsibility of housekeeping they engaged in on a daily basis. The gender differences are acknowledged in the literature28,37.

Participants perceived being able to engage in their meaningful desired recreations as one of the factors that impacted their wellbeing and felt that their wellbeing was compromised due to the lack of leisure facilities in their communities. Research has shown that leisure satisfaction can positively impact on adolescents’ psychological and physical wellbeing45. Despite the understanding of the factors influencing their wellbeing, the participants still engaged in risky behaviours such as unprotected sex, substance abuse and multiple partners. In another study mirroring these results, high school learners in Maseru, the capital of Lesotho, found that 9.9% of participants reported multiple sexual partners, 3.6% had contracted sexually transmitted diseases, 8.4% had never used a condom and 5.7% reported being intoxicated during their last sexual encounter47.

Risky behaviours like fighting and defiant behaviours emanated from the adolescents feeling misunderstood. Research has acknowledged that adolescents may engage in risky behaviours, despite knowing the adverse effects such engagement might have on them and people around them5,7,8. Substance use further impaired judgement, concentration and balance, and increased lethargy48. Similar to the literature, this study found that peer pressure was a major contributing factor to engaging in risky behaviours47-49. Additionally, some of the adolescents disclosed being sexually active and engaging in substance use by drinking alcohol and smoking tobacco47. The risky behaviours that the participants reported engaging in indicated that the participants were at risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV, experiencing teenage pregnancies, and commencing substance abuse. A study in Uganda suggested that some risky behaviours that negatively affected sexual wellbeing emanated from a lack of sexual education from an early age48,50. Additionally, the authors attributed engagement in risky behaviour to the lack of variety in leisure pursuits, and the need to escape the pressure of the traditional expectations and demands on their time created by school and household responsibilities.

Adolescence is a crucial stage of development, with implications for adulthood. This study has highlighted the need for health promotion and prevention programs for youth at risk for substance abuse, teenage pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases. The scarcity of resources dictates that health promotion programs be self-sustaining. The programs could utilise free resources in the area like netball and soccer fields, or community halls. Programs should also be conducted using games or mobile apps, as this may increase the adolescent population’s uptake, which is a strategy supported in the literature51,52. Clubs and sports activities can be used in the creation of health promotion programs. However, adolescents need to be part of the planning process from the onset to take ownership of the program. The school may be the best entry point for any organisation wanting to develop health promotion programs, as this would legitimise the activities offered in this deeply steeped cultural milieu.

Recommendations

There needs to be a discussion between all stakeholders about the increased duration of school time, including on weekends, spent by high school children in Lesotho. It may be an option to find sponsors for photocopiers to enable notes to be electronically copied, rather than the students having to write notes manually on weekends. The NGOs can also motivate the education department to equip every rural family with school-going children to have solar study lamps, as the lack of electricity was a barrier to academic engagement.

More recreational facilities like parks can be constructed in Pitseng to enable a broader choice of activities that the adolescents and their families can engage in. The existing extramural activities and organised sports at schools could be extended to take place on weekends and during school holidays. Adolescents and parents can collaborate with non-government organisations to initiate projects based on choices identified by the adolescents and that could fulfil their needs. Fun activities such as low cost and recycled crafts should be included as part of the programs, as sustainable leisure time activities. Programs should introduce new concepts regularly to attract adolescents and avoid the monotony of the same activities annually. Improving physical activity with both indoor and outdoor games will also have positive effects on adolescents’ health and wellbeing43.

Health promotion and prevention programs on substance abuse awareness, sexual and reproductive health education, stress management, anger management and improving self-esteem should be conducted using games or mobile apps, increasing uptake in the adolescent population. Adolescent empowerment groups can be established for weekends and school holidays to ensure constructive use of leisure time. The purpose of the empowerment groups would be to teach the adolescents new skills for low-cost entrepreneurship, which would enable them to gain pocket money to buy a few treats.

Future research should include adolescents of all ages to see how age influences occupational behaviour in Lesotho’s rural areas, if at all. Furthermore, additional methodology such as Photovoice could be used to give the adolescents a more significant voice and offer an opportunity for developing relevant context-specific resources and solutions for adolescents in Lesotho.

Action research using this study’s recommendation should be run in Pitseng to see if sustainable health promotion and leisure activities can be created together with the community and the adolescents.

Study limitations

The study was conducted in only one district of Lesotho and three schools in the district. If more schools in different districts participated in the study, there would have been a more holistic picture of the research phenomenon. In addition to focus groups, individual interviews could be conducted with students from different high schools in all districts of Lesotho to understand the lived experiences of adolescents in terms of the meaning of their occupational behaviours.

Conclusion

This study has deepened the insight into the occupations that adolescents in Pitseng engage in and the factors that influence their occupational choices. The dominant influences on the participants’ occupational lives included the impoverished rural context and the traditional inherited practices. The scarcity of leisure resources in the rural context led to a restricted range of leisure activities for the participants to engage in and protracted timeframes for completing basic activities and household chores such as bathing and ironing. Moreover, the traditional cultural context resulted in gendered differences in occupations. Despite the challenges, the participants showed resilience, creativity and a strong desire to improve their futures.

Acknowledgements

The University of KwaZulu-Natal is acknowledged for the remission of fees for the first year of this study as the primary researcher was a Masters candidate. The authors would like to acknowledge the participants of the study who willingly shared their experiences and beliefs.