Introduction

Northern inland Sweden is characterised by vast forested areas, mountains, often challenging weather conditions and geographically scattered small settlements. In several small towns, primary healthcare centers, also called ‘cottage hospitals’, provide continuous emergency care, as well as in-patient care in small wards1. Patients who need a higher level of care are transferred to the nearest emergency hospital. Distances are long, and road transports between healthcare facilities lasting 2–3 hours are not uncommon. Road conditions in wintertime can be difficult; thus, for urgent patient transfers, a helicopter is used when possible.

Telemedicine ‘shortens the distance’ between patients and healthcare providers, which is especially appealing in remote communities with limited healthcare access, in which recruitment and retention of healthcare professionals (HCPs) is a challenge2. Telemedicine in rural emergency care can contribute to improved care accessibility and quality3-5, avoid unnecessary patient transfers and be cost-effective6. In rural communities, positive attitudes of telemedicine users, both patients and professionals, have been found7-9. Telemedicine has, however, also been seen in the past to ‘de-localize’ healthcare services and impoverish skills that are specific to rural healthcare provision2.

In rural northern Sweden, telemedicine has been introduced by various innovative initiatives, (eg health monitoring with smart phone apps and ‘virtual health rooms’8,10). In emergency care, a local emergency team can tie additional competence to the team through video-systems – also known as ‘tele-emergency’3. In the literature, different models of tele-emergencies have been described (eg a specialist physician is being consulted remotely to assist the primary care physician in diagnosis and treatment decisions regarding a patient with a special condition3). In rural northern Sweden, a model linking a primary care physician to a smaller emergency room staffed by nurses is used. During on-call hours, cottage hospital emergency rooms are typically staffed by one nurse and one nurse assistant. A physician (general practitioner or resident) is often a resource for several cottage hospitals and can be consulted over the telephone or connected to the emergency room by video1. All patients seeking emergency care during on-call hours and in need of a physician assessment, no matter the severity of their illness/injury, can be considered ‘tele-emergency patients’ if video-conference is being used.

Patient participation has been reported to improve patient safety11 and is often promoted in modern health care, in the literature, public discourse, and in legislation. In the literature, patient participation has been defined in various ways and is often used interchangeably with concepts such as patient involvement, patient collaboration and patient-centred care. Information exchange, a respectful and trustful patient–HCP relationship and involvement in decision-making are recurring features when describing patient participation12-14.

Behaviors supporting patient participation in emergency settings, such as informing, taking time to listen to the patient, asking for their experiences and showing respect, have been described in studies, including both professionals and patients15-17. Shared decision-making is a topic of interest in research, especially regarding medical decisions18,19. Newton (2017) argued that by involving patients in decision-making in emergency care, harmful overuse of testing and treatments can be reduced20. According to Cahill (1996), involving the patient in decision-making can be a part of patient participation although this does not necessarily mean that consensus is achieved12. Time constraints, prioritizing medical tasks and the severity of a patient’s medical condition have been mentioned as hindering factors for patient participation in the emergency15,17. Nevertheless, it may be of utmost importance for the patient to have experienced involvement21.

Patients using telemedicine solutions have reported satisfactory interpersonal communication with the remote clinician7,22. Patient–HCP interaction in telemedicine has, however, most often been described in one-to-one consultations, rather than team settings.

As rural emergency care is increasingly moving towards digital communication solutions, there is a need to understand how this affects patient participation. HCPs have been identified as ‘gatekeepers’ for allowing patient participation23. It is therefore relevant to explore HCPs’ experiences and thoughts on patient participation in a tele-emergency setting. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, such studies have not been published.

The aim of this study was to explore and characterize rural HCPs’ views on patient participation in tele-emergencies.

Methods

Methodology overview

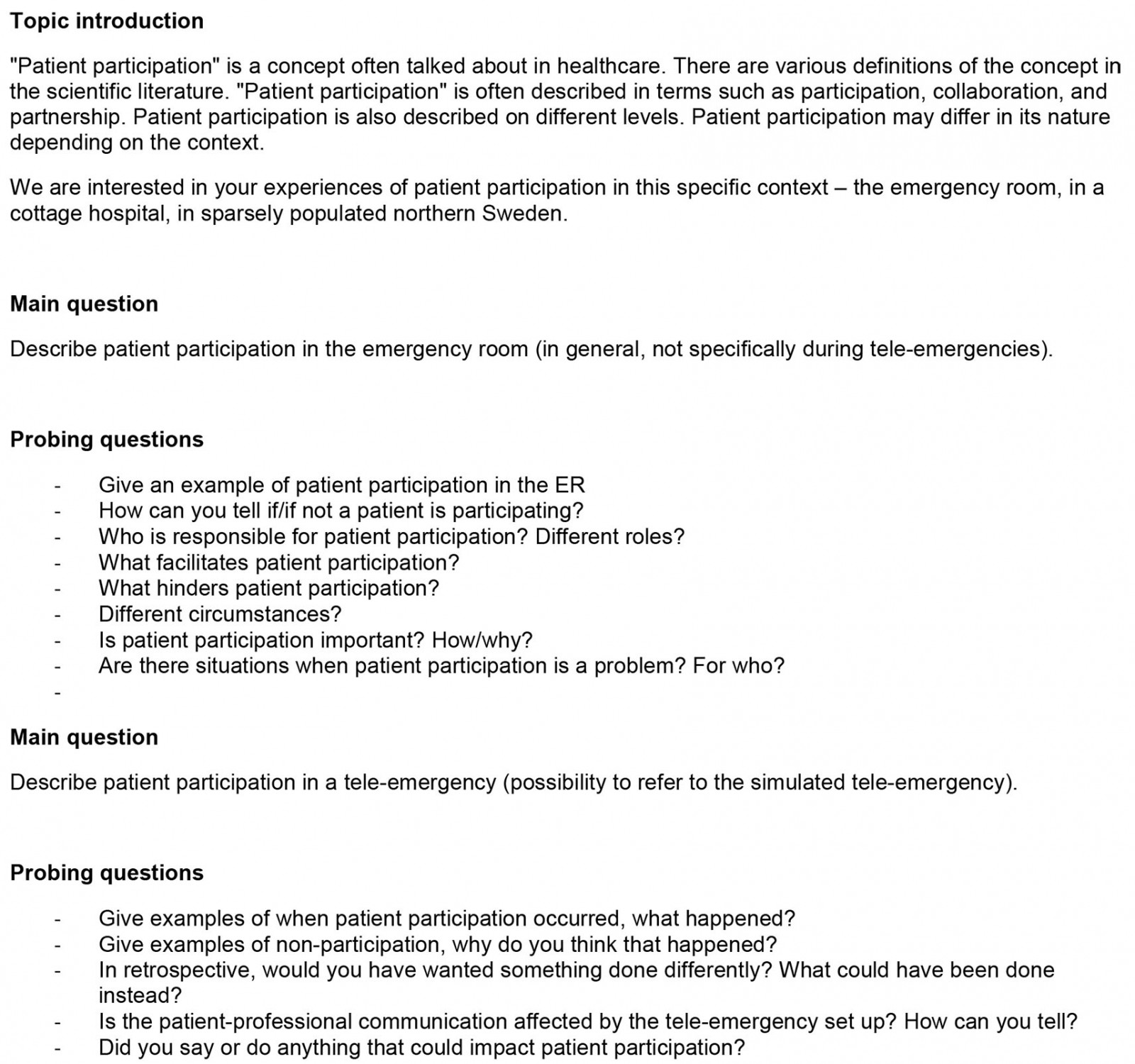

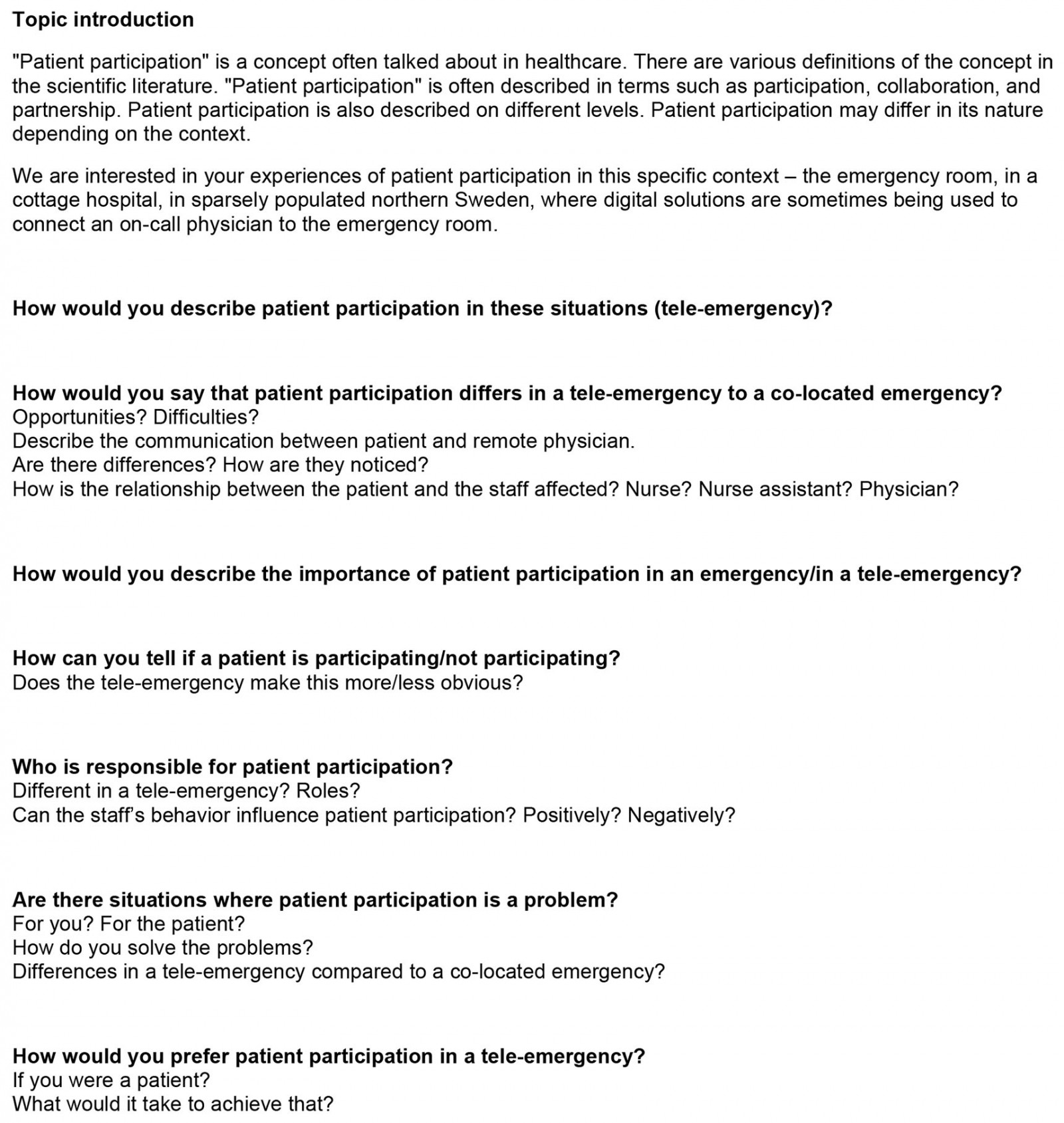

An interview-based study design, including qualitative content analysis, was used to explore HCPs’ experiences and views regarding patient participation when working in emergency care in northern rural Sweden in tele-emergencies. Semi-structured interviews in groups as well as with individual HCPs were carried out.

Data collection

Interviews with HCPs in cottage hospitals in the inland areas of the two northernmost counties in Sweden were carried out between October 2019 and June 2021. The informants were selected in two steps. First, HCPs in six rural cottage hospitals participated in the interviews in groups of three. The group interviews were discontinued in October 2020 when data saturation was considered having been reached. After the first round of data collection, it became clear that most HCPs in the region had limited experience of tele-emergencies. It was thus decided that individual interviews with HCPs with more substantial experiences of distributed teamwork in emergency care were needed. Individual interviews were carried out in a second round of data collection.

Before starting the interviews, a short description of patient participation from the literature was provided to the informants (Appendixes I, II). Thereafter, they were asked to explain what patient participation in the rural emergency room means to them, to have something to refer to when talking about their experiences of tele-emergencies. All interviews were audio-recorded. The group interviews were carried out at the healthcare teams’ workplaces (by authors HD and MH). For group interviews a semi-structured interview guide was used (Appendix I). The individual interviews were performed over a video-conferencing system (by author HD), using a revised interview guide (Appendix II) with informants participating either from work or from home. The first author was the main interviewer in all interviews. Author MH was present during the group interviews, asking additional follow-up questions.

Participants

Informants to the group interviews were recruited by contacting managers at cottage hospitals in the inland region of Västerbotten county. Volunteers from the staff were booked for half-day team trainings and interviews at their facilities. The team trainings consisted of simulated scripted emergency scenarios with a standardised patient (actor). Teams of three – a physician, a nurse and an assistant nurse – trained in co-located teams and in distributed teams (ie the physician participated from another room by using a video-conferencing system). Some teams included an extra nurse, instead of an assistant nurse. In all the cottage hospitals video-conferencing systems existed, but in none of them was it frequently used at the time of the study. The team training served as an experience of tele-emergencies that the informants could reflect on during the interviews.

Informants for the individual interviews were recruited by contacting managers at other cottage hospitals, both in the counties of Västerbotten and Norrbotten. Staff with experience from at least five real-life tele-emergencies were eligible for inclusion.

Data management and analysis

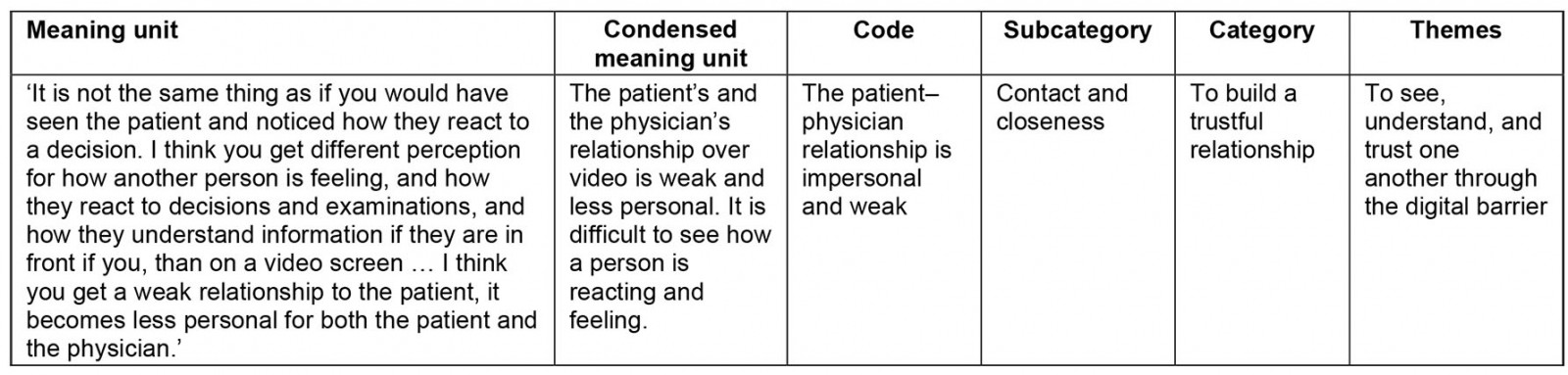

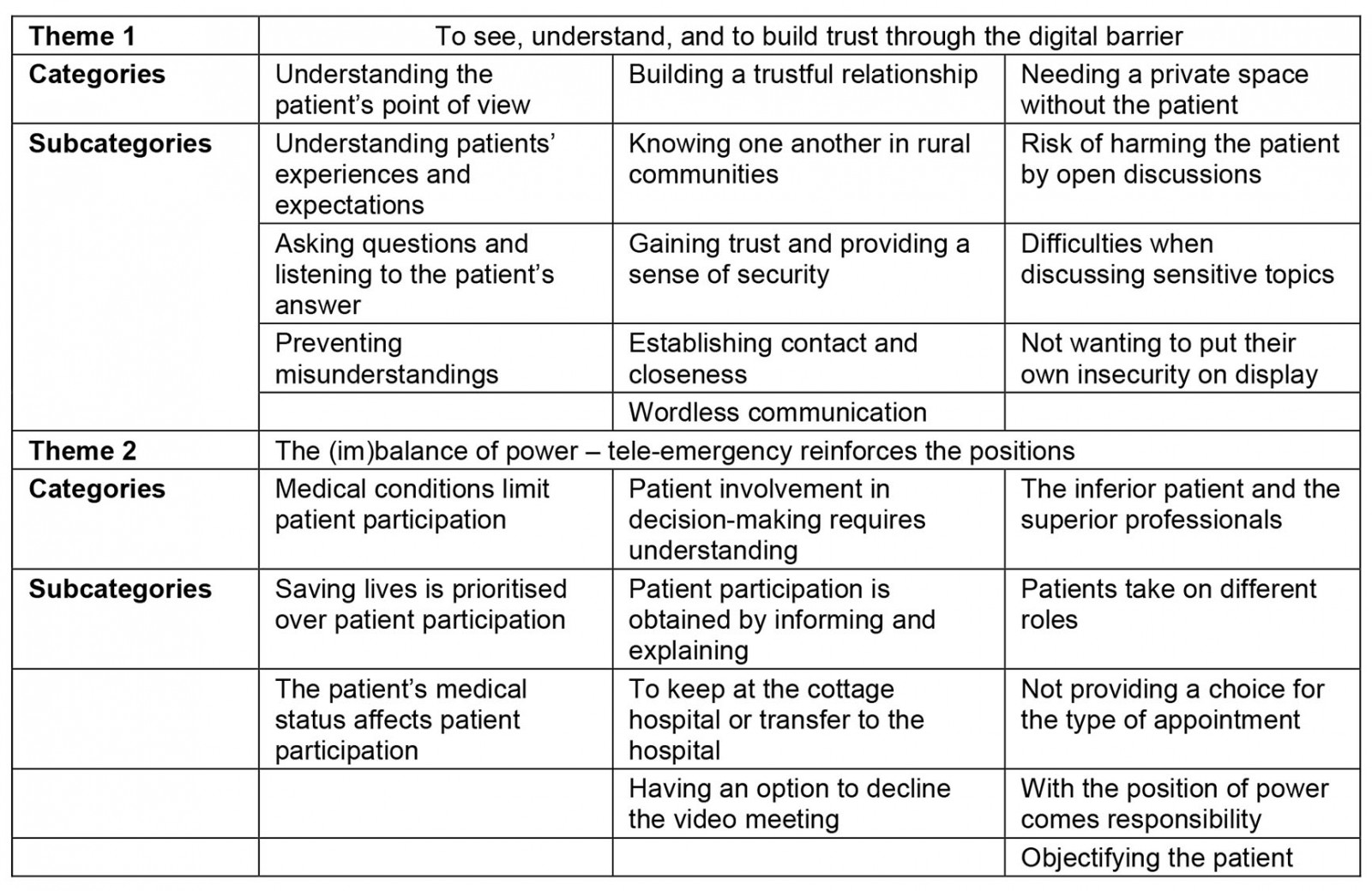

The interviews were transcribed verbatim and read through by all authors to get a sense of the whole. The manifest content of the interviews was processed in a qualitative content analysis, as described by Graneheim and Lundman24. Meaning-bearing units were condensed (by authors HD and JC) to a more manageable number of words, thereafter open coding was conducted (by authors HD, MB and JC). The codes served as ‘labels’ to organise the data in subcategories, categories and, finally, themes (Table 1). The analysis process was not linear; changes were made back and forth during reflections in the research group, both by gathering around a table, in creative processes by using paper notes and making mind maps (HD, MB and JC), as well as in several email rounds (HD, MB, MH and JC). Disagreements were solved during these discussions and consensus was reached on the final result. A high level of abstraction signifies the category level, while the themes can be regarded to be of a more interpretative nature25. As a validation, author MH and one of the informants from the individual interviews checked the material for its coherence with the views shared during the interviews and experiences from tele-emergencies.

Table 1: Example from the qualitative content analysis process

Ethics approval

All participants were informed orally and in writing of the purpose of the study and consented in writing to participate in the study. Ethical conduct was governed by the Declaration of Helsinki.

The Swedish Ethical Review Authority concluded that the project (Dnr 2019- 00148/Dnr 2020-07207) was exempt from ethics approval according to Swedish legislation. The committee also stated that they found no ethics issues in the study protocol.

Results

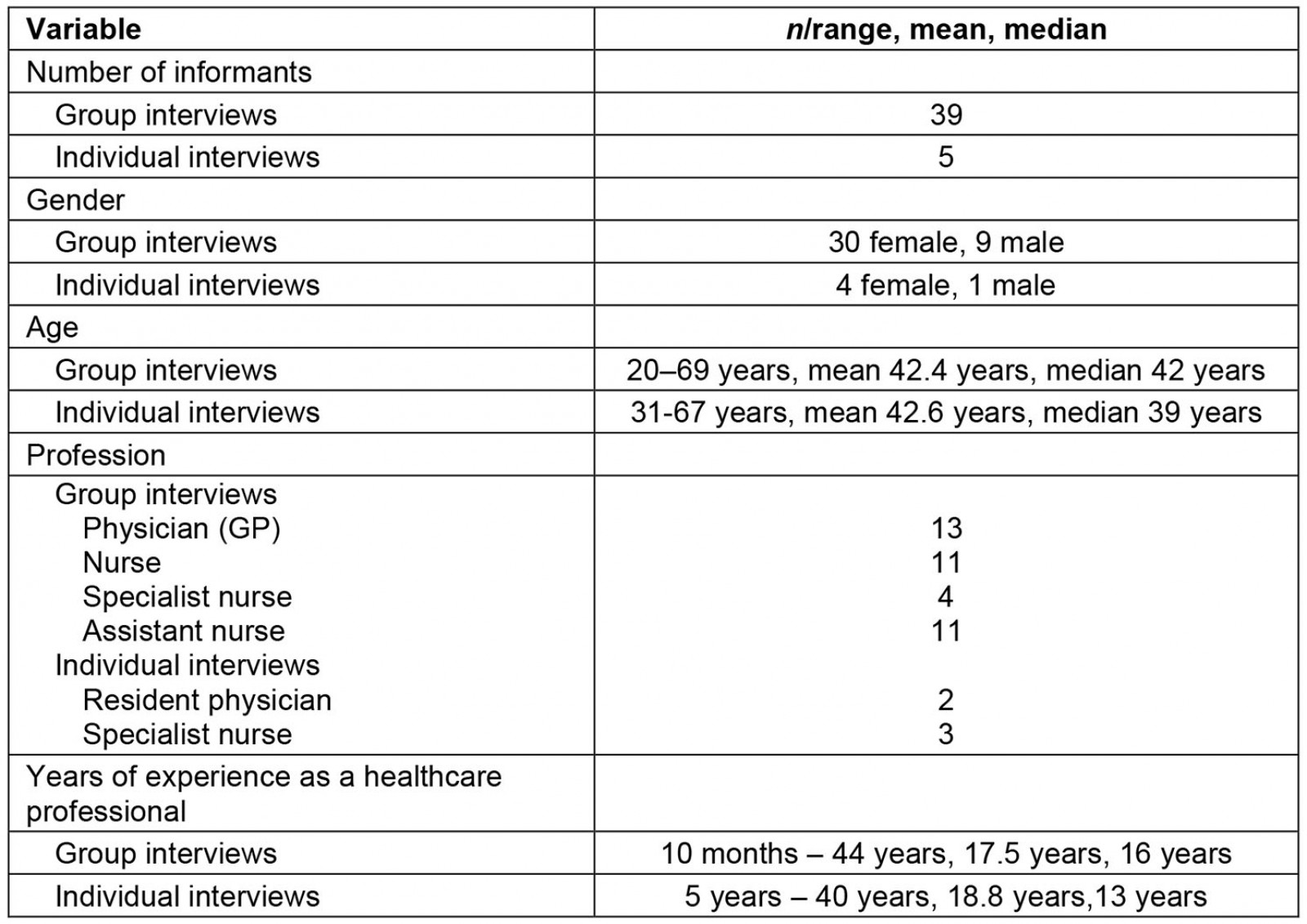

Thirteen multiprofessional group interviews were performed, with three HCPs in each. In the second round of interviewing, five individual interviews were performed. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 2 (Table 2).

Two themes, six categories and 19 subcategories emerged from the data analysis (Table 3).

Table 2: Participant characteristics

Table 3: Study themes, categories and subcategories

Theme 1: To see, understand, and to build trust through the digital barrier

The core of this theme is the interpersonal relationship between the patient and the HCPs. It contains descriptions of how to get to know and understand the person with the illness or injury, and of the challenges to gaining the patient’s trust, despite the physical distance between the patient and the physician during tele-emergencies.

Understanding the patient’s point of view: Understanding patients’ experiences and expectations regarding tele-emergencies was mentioned as important, since they could vary between patients. Patients often called the national medical advisal service and were referred by a nurse to a healthcare facility (eg a cottage hospital). An informant stated that the patients were not always informed about the tele-emergency set-up. Thus, patients were sometimes surprised when they were introduced to an online physician. However, none of the informants described negative reactions when patients learned about the tele-emergency, rather a curious and collaborative attitude, even though not all patients were familiar with video meetings.

Asking questions and listening to the patient’s answer were described as being important to get a picture of the patient as a person, and not just as a medical condition. This communication was described similarly, whether the team was co-located or distributed. When trying to get to know a patient, the informants mentioned open questions and time to listen as helpful strategies. Listening to a patient was, however, not always regarded easy: there were times when the professionals perceived a patient or a next of kin to push the limits for what is ‘too much’ talking. A nurse described that during tele-emergencies, when a patient was ‘too talkative’, she took on a role of directing the conversation between the patient and the physician.

Elderly people often talk a lot about other things ... when I am there, I direct the conversation all the time to what the problem is, not to what’s going on at home or what happened last year, and so on. (Nurse, participant 4)

In tele-emergencies, the informants saw the potential of preventing misunderstandings that could have led to patient harm. When patients heard what the professionals were talking about, they could correct inaccuracies, thus enhancing the understanding of the patient’s point of view.

I make an interpretation of what the patients tell me, if they are in pain it may be difficult to relate to, but I try my best to get an idea of what they are going through. When the patient hears me reporting to the physician [on the video] they can interfere in another way … misunderstandings can be corrected along the way when information is repeated. There is an advantage in that way that the patient hears what we are saying, when we talk out loud. (Nurse, participant 16)

Building a trustful relationship: Knowing one another in rural communities was often brought up in the interviews as typical for the context and important for patient participation. In small rural communities, HCPs and patients very often already had an established relationship, either from primary care, or as neighbours or friends (eg hunting partners). This was often explained as contributing to continuity, mutual trust and motivating the professionals to make a special effort for their patients. A common opinion was that gaining the patient’s trust in a tele-emergency was easier when you already had an established relationship.

If you have met before, you will trust the medical assessment … and if you get to see the person [on the screen] you are used to from before, of course, I imagine you feel more involved as a patient (Physician, participant 8)

In a tele-emergency, the on-call physician was not always from a patient’s local community; this was perceived as an obstacle in gaining the patient’s trust. In these cases, the nurse’s knowledge of the patient, but also local knowledge (eg about distances and road conditions) was regarded as crucial. The nurse’s relationship with the patient was also mentioned by some physicians as important when making decisions ‘against best practice’, according to a patient’s wishes. This type of decision requires mutual trust, and when the physician was online, the nurse could ‘vouch for’ the patient.

Gaining trust and providing a sense of security were described as both prerequisites for, as well as characteristics of, patient participation. Some of the informants claimed that it was difficult for the physician on the screen to gain a patient’s trust because you could not easily interpret body language. On the other hand, there were physicians who thought that being behind the screen provided an opportunity to keep calm in a stressful situation and an overview of the room, while having time to read up on treatment protocols and medical charts. Thus, the physicians felt they would appear more reliable and competent. Some nurses pointed out that their role in the medical assessment during tele-emergencies was crucial for the patient’s trust in the team; when examining a patient, a task traditionally performed by the physician, the nurses felt a need to show proficiency. The nurses feared that they would be perceived by the patient as incompetent if they needed guidance by the physician in tasks in which they were inexperienced.

Several informants thought that the presence of a physician, whether it was physical or digital, was important for patients to feel secure, as the physician was perceived as an authority and a symbol of security by many patients.

Establishing contact and closeness during an emergency were described as important for a good patient–HCP relationship, thus, facilitating patient participation.

In the past, before having the option of using secure video connections, the physicians were consulted by telephone when unavailable in person during on-call hours. The informants with such experience found the video to be superior for the patient–physician connection. Many of the nurses found this to reduce their workload, because they had previously often acted as intermediators between the physician and the patient. When audio quality was optimal and the patient communicated directly with the physician on the screen, patient participation was perceived as benefiting from the video connection.

It was also described as challenging to achieve the perception of closeness in tele-emergencies. A physician said that she missed the initiation of contact with the patient, since the physician rarely was connected to the emergency room from the start – the physician ‘entered’ in the examination phase. She proposed that the initial conversation between patient and physician would benefit from being conducted over a tablet, for a close-up face view. It would augment the connection and increase the feeling of closeness.

The nurses described feelings of being torn between the patient and the physician, not being able to communicate mindfully with either, often because of technical shortcomings, such as poor audio quality or the placement of the screen. A nurse reflected on this after the team training sessions:

It was difficult to keep focusing on the patient while trying to connect [with the physician] and listen to the physician’s prescriptions and at the same time listening to the patient […], because the screen with the physician was behind me, I had to turn away from the patient […] it felt unprofessional and not safe … (Nurse, participant 5)

A nurse assistant described how she connected with the patient during one of the training sessions, when the nurse was occupied discussing with the physician, by being close and touching.

And then I stroke her shoulder, she thought that felt really good. (Nurse assistant, participant 21)

Wordless communication was described as ‘the feeling in the room’, facial expressions and other subtle gestures that could reveal if the patient did not understand, agree or if he/she hid important information (eg about domestic violence). Wordless communication was perceived as a challenge when using video connection.

There is a difference between a face-to-face meeting and if you communicate from a distance. It is really much more difficult from a distance. When I see a patient face-to-face, I get thoughts and ideas about their symptoms, when I look at their face, sometimes how they react. I get more information when I am in direct contact with the patient. (Physician, participant 10)

Knowledge and experience with online video meetings were considered important for the wordless communications during a tele-emergency, both for patients and staff. Patients without experience with online meetings were perceived as insecure about how to interact with the physician. A physician explained that establishing eye contact with the patient was difficult. Knowing where to look was tricky; if you looked at the patient on the screen instead of in the camera, it seemed to the patient as if you were looking elsewhere.

Figure 1: A typical tele-emergency set-up. The screen is placed behind the patient, which does not allow for face-to-face communication between the patient and the physician. The nurse sometimes becomes an ‘intermediator’. The nurse assistant can provide comfort by moving closer to the patient.

Figure 1: A typical tele-emergency set-up. The screen is placed behind the patient, which does not allow for face-to-face communication between the patient and the physician. The nurse sometimes becomes an ‘intermediator’. The nurse assistant can provide comfort by moving closer to the patient.

Needing a private space without the patient: In tele-emergencies, communication was overt, which was discussed as problematic at times. The informants described the need of private conversations within the team, without the patient. Reasons for this were threefold. First, the informants were worried that there was a risk of harming the patient by open discussions. They were concerned that it would be stressful for the patient to listen to medical discussions and possibly misunderstand what was being said.

Second, there were difficulties when sensitive topics were mentioned, such as substance abuse and violence. To avoid an uncomfortable situation, the informants instead found other ways to communicate within the team, eg muting the video and calling each other on a regular phone line.

Sometimes you have a gut feeling of things that you don’t want to express in front of the patient, then I choose to talk to the physician in another way. (Nurse, participant 16)

Third, when discussing a working diagnosis or asking questions within the team, some informants felt that they did not want to put their own insecurity on display. The informants described a wish to maintain their ‘professional image’, not showing the patient their own insecurity.

Theme 2: The (im)balance of power – tele-emergency reinforces the positions

This theme contains descriptions that mirror the power relationship between the patient and the HCPs. As the theme title suggests, the patient and the professionals were not participants in the tele-emergency on equal terms. Although the intentions of the HCPs were good, they often had the prerogative to interpret the situation. The emergency was often seen as purely medical by the professionals, not always considering the psychosocial and emotional aspects that could be important to the patient. One of the pitfalls in tele-emergencies could be that it reinforced an already existing power asymmetry.

Medical conditions limit patient participation: Saving lives is prioritized over patient participation. Communication within the medical team over the video connection was described as demanding, sometimes due to poor audio quality. Thus, having to explain medical issues in a comprehensive manner to a patient was perceived by some of the informants as adding workload in an already stressful situation.

If we talk to one another by using terms that the patient doesn’t understand, then explaining [to the patient] would be an additional task. […] You can’t handle any additional tasks in those situations. (Nurse, participant 37)

The patient’s medical status affects patient participation. Naturally, an unconscious patient cannot be involved or collaborate; however, the informants pointed out that some medical conditions hindered patient participation in tele-emergencies because of the difficulty interacting with and relating to the physician on the video screen. Such medical conditions mentioned were cognitive impairments, dementia, hearing loss, severe pain, dizziness, stroke and aphasia.

Patient involvement in decision-making requires understanding: Patient participation is obtained by informing and explaining. The informants all agreed that the patient needed to understand how the HCPs perceived and dealt with a medical situation. In a tele-emergency, the patient was exposed to all communication within the medical team, which some of the informants suggested increased patient understanding. Sometimes, nurses and nurse assistants said that they needed to help the patient to understand what the physician said, by ‘translating’ medical language to lay terms. If the audio quality was poor the patient also could need help to understand what was being discussed.

I realized that [the patient] doesn’t hear what [the physician on the screen] is saying, and I am standing in the middle trying to mediate, trying to interpret. (Nurse assistant, participant 2)

When discussing patient involvement in decision-making, the informants especially referred to decisions that were common to discuss with the patient in this rural context, for example whether to keep a patient at a cottage hospital or transfer to the hospital. The informants described that compromises between the physician and the patient occurred; for example, when a patient was reluctant to being transferred to the hospital, they may accept staying at the cottage hospital overnight, although the physician would prefer admission at the hospital. Such compromises were found to be difficult to make for physicians in tele-emergency, because of the perception of increased interpersonal distance.

The ‘inferior’ patient and the ‘superior’ professionals: Patients take on different roles during emergencies. An active patient was described as someone who asks questions, participates in the team conversations and interacts with the physician on the video screen. The passive, submissive patient was described as someone who ‘surrenders themselves’ to the HCPs, either because they are unfamiliar with the situation, or because they relax and feel safe and taken care of.

Regardless of the patient role, healthcare was ‘not providing a choice for the type of appointment’. This was discussed as a sort of injustice: a patient with acute illness seeks care at the closest emergency room; it is not their choice whether they meet an entire healthcare team there, or if the treating physician is there on a video screen, or even not present at all (only being consulted over telephone if necessary). In the tele-emergency, some of the informants advocated that the patient should have an option to decline the video meeting with the physician, as they feared that the video meeting would be perceived by some patients as violating their integrity.

First, you ask the patient ‘is it ok if the physician takes a look over video’. (Nurse, participant 4)

Many of the informants agreed that with the position of power comes responsibility of promoting patient participation. In a tele-emergency, most informants thought that the nurse had a key role in facilitating patient participation, compared to the traditional co-located team setting, where opinion on such responsibilities was more varied. One physician said that he took on a ‘consulting role’ in the tele-emergency and left the patient principally in contact to the team members physically close, thus leaving them with the responsibility of promoting patient participation.

The informants often talked about the lack of involvement of the patient as a professional shortcoming. They mentioned reasons for this, such as stress, complex technical tasks, focus on the conversation over video, and being distracted by the monitors and alarms.

Objectifying the patient: The informants described that in tele-emergencies, they tended to focus on team communication, rather than information to the patient. Some informants reflected on how it may affect the patient’s experience of involvement or, rather, exclusion, when being talked about in the third person and experiencing procedures without proper explanations. Several of the informants said that they imagined this type of ‘objectifying behavior’ must have felt very unpleasant to the patient. The patient was already in an exposed position in the emergency, and the inferiority might be amplified through the tele-emergency.

The patient may lie there without the shirt on, be hooked to the ECG, you may have had to cut open their trousers. They are already exposed, and then this giant physician on the screen is looking down on them. (Physician, participant 8)

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore rural HCPs’ views on patient participation in tele-emergencies. The key findings were that the tele-emergency set-up challenged the trustful patient–HCP relationship and that the already existing power asymmetry in the care relationship was at risk of being reinforced, leaving the patient in an even more vulnerable position. This article includes descriptions of risks and benefits concerning patient participation in a tele-emergency set-up from rural HCPs’ perspectives and brings attention to the complexity in the patient–HCP relationship, interaction, and to teamwork aspects impacted by the tele-emergency set-up.

In the first major theme, ‘To see, understand, and to build trust through the digital barrier’, the nature of the patient–HCP relationship and how telemedicine impacted it were portrayed. The trustful relationship between the patient and the HCPs has previously been described as a prerequisite for patient participation12,14. This study illustrates that the development of mutual trust was hampered by the tele-emergency set-up.

First, an alternative group dynamic, compared to the traditional set-up, where the physician typically examines the patient, was identified. Apparently, the relationship between patient and HCPs changes, but also the teamwork is affected; the physicians experience difficulties in interacting with the patient, while the nurses experience being ‘forced’ into taking an intermediator’s role. With the physicians online, the nurses are expected to perform the physical examination, as well as administering drugs, a typical task for nurses. The tele-emergency added additional workload on the nurses, possibly explaining the experience of their attention to the patient being divided. The nurse assistants were indirectly pushed to move physically closer and connect with the patient when the nurse was busy talking to the physician. The nurse assistant’s interaction with the patient may therefore have been crucial for the patient’s sense of understanding and control.

Second, the importance of knowing one another and building trust based on prior relationships and social networks was emphasised by many of the informants as typical for this rural context, in which social capital and sense of community belonging have previously been reported to be strong26. In this study, the tele-emergency was viewed as an obstacle in gaining the patient’s trust, but building trust seemed to be a two-way street; trusting and collaborating with the patient seemed just as difficult for the professionals. The physical distance and interacting with a physician who was unfamiliar created new emergency team constellations. This lack of personal relationship was described as hindering the involvement of patients in decision-making, especially regarding decisions on admission to the cottage hospital’s small ward or transfer to an emergency hospital, sometimes hundreds of kilometres away.

The personal relationships between HCPs and their patients in rural northern Sweden was recently reported as crucial for older patients, when engaging in primary care tele-health initiatives. In particular, the contact with familiar nurses was important27. As previously described, HCPs experience the very essence of working in a cottage hospital as knowing your patients, being familiar and making that extra effort1. In this study, the familiar relationship was often compromised in tele-emergencies. The more ‘anonymous’ contact between patients and HCPs, perhaps more common in urban emergency departments, might in this rural context be a game changer – it came with the promise of accessibility and equality, but maybe at the expense of personal relationships and familiarity.

Although the informants viewed the open, familiar and trustful patient–HCP relationship as important and positive, they described that boundaries were needed, based on the assumption that it was important for patients’ sense of security, and their own personal integrity. The informants were not comfortable in letting the patient fully be part of the medical team; they needed ‘privacy’ to have professional talks in between. Delmar (2012) suggested that both closeness and distance to the patient could in their extremes damage the relationship28. Maybe the descriptions of the needed boundaries illustrate the professionals striving to find a balance in achieving an empathic, sensitive and yet professional bond with the patient.

In the second theme ‘The (im)balance of power – tele-emergency reinforces the positions’, the power balance between the patient and the professionals is described. According to Delmar (2012), HCPs need to acknowledge an always-existing power asymmetry, where the patient never has the upper hand in the relationship28. The results of this study indicates that the tele-emergency set-up in some cases may reinforce this imbalance, for example by complicating the communication between the patient and the remote physician and adding to the split attention of the nurses. Many informants identified unintentional objectifying of the patient (eg talking about the patient in third person) as a professional shortcoming. This indicates that proper training for HCPs in patient-inclusive team communication in tele-emergencies may contribute to a higher level of patient participation.

Although the study participants described difficulties with the digital solution, they also saw its potential in facilitating patient participation. Communication within the team became more overt in tele-emergencies, which was seen as a means of keeping the patient informed, thus sharing knowledge (and power) with the patient.

Gibson et al interviewed patients and carers with experience from a telemedicine assessment of acute stroke, a similar telemedicine set-up as in this study, and found that involvement in decision-making was described as satisfactory, especially when the remote physician and the patient/carer communicated directly, without an intermediator22. If efforts on enhancing the patient–physician communication are being made (eg more optimal placement of the screen and camera, or technology supporting a more face-to-face-alike interaction (eg a tablet)) the power imbalance might be reduced, and the nurses may have some relief in workload as well.

When studying patient participation, it is important to understand HCPs’ thoughts and attitudes to understand the patients’ situation. However, real-life patient experiences are crucial for a full picture. A suggestion for future research is investigations of patients’ experiences and preferences regarding patient participation in this specific context. Such knowledge could in the future contribute to the development of best-practice guidelines for tele-emergencies.

Limitations

This study is based on descriptions of patient participation in tele-emergencies provided by 44 HCPs in a large geographic area in northern Sweden. Although interviewing was extensive, the results mirror the views of HCPs with mostly limited experiences in tele-emergencies, of which some were gained through tele-emergency training sessions. In northern Sweden, despite a strong push from policymakers, telemedicine was at the time of the study rarely used in emergencies. Although there was generally little experience of tele-emergencies among staff in the cottage hospitals, the researchers were able to reach some HCPs with more experiences.

As always, the results need to be interpreted with caution, and only be generalised for similar conditions of care. The study contributes knowledge on areas needing improvement for patient participation in tele-emergencies, especially for inexperienced telemedicine users.

Conclusion

This study highlights tele-emergencies' impact on patient participation in a rural setting, from HCPs’ point of view. A main concern reported was that the important familiar physician–patient contact was replaced by, to the patient, an ‘unknown doctor on a screen’. The communication between the remote physician and the patient was demanding, which altered the group dynamics, forced nurses to take an intermediator’s position, and subsequently affected the trustful relationship between the patient and the HCPs. The tele-emergency set-up reinforced the power positions, risking weakening the patient’s opportunity for involvement. To avoid such situations, training of professionals in patient-inclusive video-communication, as well as attention to technical solutions to enhance patient-physician communication, are suggested.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by The Kamprad Family Foundation for entrepreneurship, research and charity.