Introduction

South Africa has seen a progressive and rapid expansion of health professions education outside of central academic hospitals from as early as 1992, across a range of contexts and within the majority of the institutions offering health professions education1-3. These decentralised training sites serve as essential components of healthcare education reform through contextually relevant training along a continuum of care4-9. Although the term decentralised is commonly used in the literature, we prefer the term distributed to emphasise the notion that health care is distributed along a continuum and that facilities outside of the tertiary academic hospital are not separate or less relevant. The aim of distributed clinical training is not to decentralise medical education at the expense of the teaching value of central hospitals, but to expose students to the continuum of care3. Indeed, the academic success of distributed training has been shown to be equal to or in some cases better than that of centralised academic hospitals; the academic viability of distributed training is thus clear10.

Distributed training sites that have been established in South Africa have also helped accommodate a growing number of students in the health professions programs1,11 and will need to increase further as health professions training is set to expand to meet demand12. Given this expected increase in the quantity of distributed training sites for health professions education, this article’s contribution is premised on the importance of optimising the quality of the teaching and learning experience at distributed training sites, particularly in rural areas.

Following global calls for the transformation of health education, most notably from the Lancet Commission on education of health professionals for the 21st century13, a panel was appointed by the Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf) in 2018 to contextualise the recommended health education reform in South Africa. To aid in the transformation of health professions education to meet the needs of society, the panel recommended that health science faculties ensure greater exposure to rural settings during training to help bridge the divide of health professionals in South Africa, with a prescribed minimum amount of clinical time to be spent in rural areas12. Exposure to the complexities of rural health care is considered essential in the development of competent South African health profession graduates2,14 and therefore needs to be considered in the process of advancing the number of distributed training sites, collectively referred to in this study as the distributed training platform (DTP).

The described rise in distributed clinical training of health professionals has highlighted the need for adequate onsite clinical supervision in areas removed from the traditional academic ‘home’, a function that is crucial for the quality training of students in the rural healthcare context15-18. Student supervision on the DTP relies predominantly on local clinical professionals and includes clinical supervision within a healthcare facility and the local community where they train19,20.

Clinical supervisors (also referred to as ‘clinical facilitators’ in the literature) are defined as qualified healthcare professionals who are stakeholders in the training platform responsible for students’ professional and skills development on site. Their role encompasses liaison duties between university staff, students and other facility staff as well as assessment. They act as role models while responding in a student-centred manner, which requires mutual trust between supervisor and student21,22 while taking on the clinical responsibility for the patient care provided by the student, which can be a significant stressor for the clinical supervisor. Rural distributed training depends heavily on the capacity and competency of the clinical supervisors in these rural healthcare facilities, whose experiences are important to understand if health science faculties are to ensure optimal support for student training at these sites23.

Existing recommendations and guidelines, developed to prepare for the challenges of distributed rural training specific to South Africa, make specific mention of the resources, responsibilities and relationships required to support onsite clinical supervision12,18,24. The 2018 ASSAf report recommends recruiting and integrating faculty members on both traditional and non-traditional platforms to facilitate learning and to understand the teaching context in these environments12. The SUCCEED (Stellenbosch University Collaborative Capacity Enhancement through Engagement with Districts) framework for effective distributed health professions training provides a comprehensive tool for establishing new clinical training sites and ensuring sustainability of relationships, resources, responsibilities and collaboration with respect to the South African context25. A recent publication related to this framework proposes 12 tips for establishing distributed training sites, which include recommendations related to identifying, equipping, supporting and acknowledging clinicians on the DTP18. It also recommends the appointment of a dedicated coordinator identified by the training institution, who can act as a liaison between the academic institution, the students, the health service and the local community.

Research into the perceptions of clinicians on the DTP regarding their role shifting and experience as clinical supervisors has been done both internationally21,22,26 and locally, specifically in relation to South Africa’s first Rural Clinical School (RCS)3,23. In most cases, the role of supervising students’ learning and all the related responsibilities are added to the existing workload of clinicians appointed by the health facility. Clinicians in the workplace are often concerned about the perceived burden students can place on their clinical load in an already strained human resources for health environment in South Africa3,23. There are, however, benefits relating to the presence of final-year students training on a distributed platform where they reportedly contribute and, in some cases, add to existing healthcare services, which is especially true when students spend extended periods of time at a clinical training site25,27-29.

On top of the clinicians’ clinical workload and additional teaching responsibilities, they are also drawn into various coordination functions. Onsite coordination of training is essential to ensure students are accommodated safely; have access to adequate and reliable transport to mobilise to and around the clinical training platform; and have access to learning spaces, study materials and information and communication technology6,18,27-32. Students, especially those who are placed far from their support systems and who are at risk of social isolation, also require access to food, recreation facilities, religious institutions and support for their psychological and physical health27. Furthermore, coordination of the students’ program on the DTP also includes the coordination of logistics such as clinical rosters, the orientation of new rotations of students to the site and the community, and the introduction of students to available support structures18,33. Clinical supervisors on occasion are recruited to identify learning opportunities, assess students, engage in research and adapt learning outcomes. Sherbino et al (2014) define an active clinician involved with applying theory to practice and engaged in educational scholarship as a clinician–educator34, adding an additional dimension to clinical supervisors as they are tasked with ensuring that practical clinical training and the prescribed learning outcomes speak to the needs of the local health system. Elsewhere in the literature, terms used to describe people in these positions are ‘director of clinical education’33 and ‘clinical coordinator’32. Understanding the experiences of clinical supervisors who are also tasked with academic and coordinating responsibilities on the DTP is an important part of preparing for an increase in DTP across South Africa.

The challenges of juggling roles in distributed training sites are compounded by the challenges of the rural setting35,36. The logistic and financial resources required to initiate and maintain rural distributed training far from the academic home makes regular faculty visits for support and training of clinicians difficult and expensive27. The increasing number of students from more than one health professions program working and living on the DTP adds an additional layer of complexity to the responsibilities of clinical supervisors. Healthcare professionals and students also face the additional stress of grappling with the socioeconomic hardships and health inequities endemic to rural areas, the symptoms of which manifest in the patients they care for in the clinical environment37.

Various studies recommend the appointment of dedicated or at least part-time personnel to take responsibility for the administrative arrangements and/or academic development that is essential to the sustained success of a distributed training site25,31. In reality, in South Africa, having both a clinical supervisor and dedicated coordinator role is difficult due to the lack of human and financial resources at rural sites. In the absence of a dedicated staff member on site, the academic coordination functions become the responsibility of the local supervising clinicians involved with the students’ training, thereby adding an additional dimension to the responsibilities they already have. If these clinicians do not have the capacity for this task in addition to their clinical and teaching roles, it can negatively affect the students involved, especially in an already under-resourced rural environment15,38.

In the case of the development of the RCS in Worcester, South Africa, linked to the Stellenbosch University, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, local health professionals were formally appointed on site in Worcester in a dedicated role to coordinate academic (including clinical) and logistic activities at the RCS and to support students from the various training programs. This formalisation of appointment speaks to the evolution of the clinician–academic outside of the traditional academic home39. The role comprises that of a clinical supervisor, clinical educator and a coordinating role that we collectively term ‘academic coordinator’. Buccieri et al (2012) define this type of position as being ‘expected to fulfil faculty roles of teaching, scholarship, and service, while meeting the responsibilities unique to the position’39. The initiative of having dedicated academic coordinators on site in Worcester provides an opportunity to explore the roles and experiences of these ‘academic coordinators’ and to reflect on the complexities and benefits of being a clinician–academic outside of the traditional academic home.

While there are existing guidelines for the establishment of distributed training sites and the support for clinical supervisors, exploring the experiences of rural academic coordinators can help to elaborate how this support can be practically operationalised in a rural setting. This article aims to explore the experiences and perceptions of the academic coordinators working at the RCS in South Africa and provide insight into what works and what remains a challenge. Recommendations are put forward to enhance the sustainability of the DTP.

Contextual background

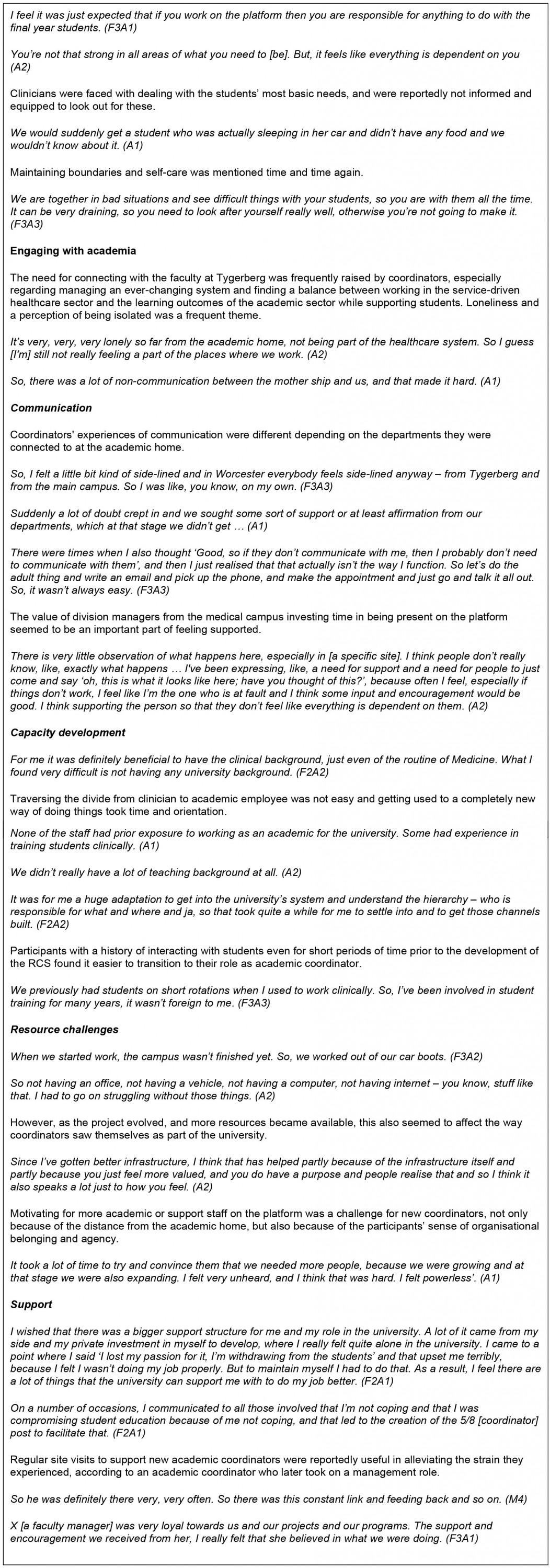

Stellenbosch University opened the first RCS in Africa, offering year-long rural training for medical, occupational therapy and human nutrition students from the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences (FMHS). In addition to longitudinal placements, shorter rotations of medical, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, human nutrition and speech, language and hearing therapy students have also been taking place since 2013. Students from FMHS spend anywhere between 4 weeks and 10 months on the rural training platform placed in the same communities or healthcare facilities as students from other degree programs. This ‘sharing’ of clinical learning spaces enables academic coordinators to share administrative responsibilities and combine learning opportunities to address the required outcomes for more than one degree program. Several rural towns in the Western Cape make up the composition of the RCS, which is mapped out in Figure 1.

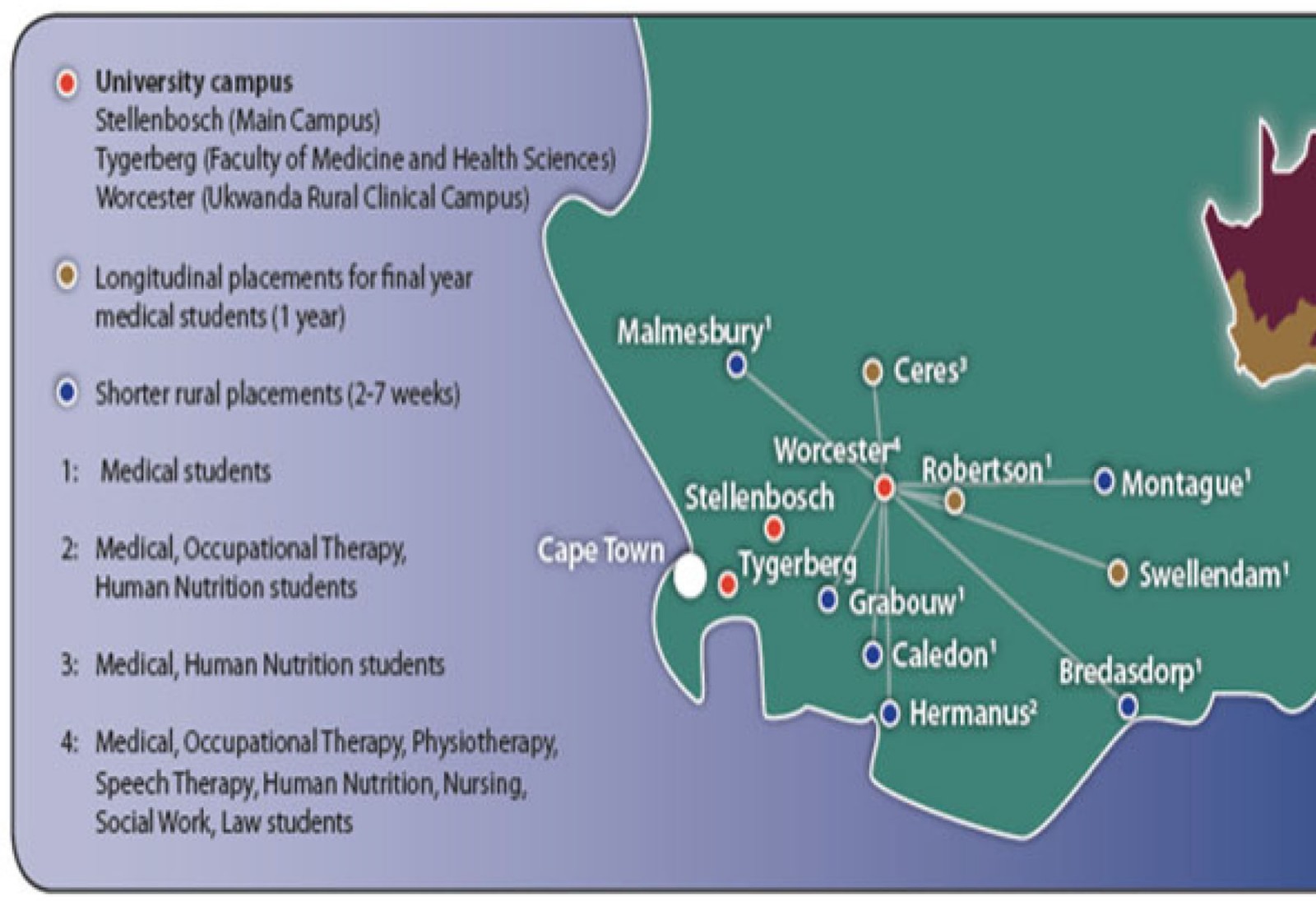

Traditionally, in order for students to benefit from learning opportunities on the DTP, faculty staff (programmatic coordinators) based at Tygerberg (the academic home, some 100 km away) are responsible for establishing and maintaining relationships with community stakeholders through active engagement. This engagement usually spans across multiple organisations, facilities and levels of care in one community, including, for example, Department of Health facility staff and management, non-governmental organisations, private practitioners, community-based organisations and local training institutions. At the RCS, however, the establishment and maintenance of these relationships was allocated to an onsite academic coordinator, who acted as a liaison between the community and training institution as well as a clinical supervisor. Without the presence of these onsite academic coordinators in Worcester, the students would rely on distance support from staff at the Tygerberg campus in Cape Town. Table 1 gives a detailed breakdown of the number of academic coordinators employed at the RCS and the number of students working on the platform over the years.

As part of a large-scale historical review of the establishment of the RCS carried out in 2017, research exploring academic coordinators’ experiences of working at the RCS was conducted to gain insight into their perceived roles and responsibilities, the challenges they faced and the recommendations they have for further expansion of the rural DTP. This article explores the recommendations made by participants in relation to the perceived enablers and challenges they experienced while involved in the development and maintenance of clinical training at the RCS.

Two of the authors (JM and HD) were involved with the initial development of student training at the RCS from as early as 2012 and come with first-hand experience and lived insight into the process of being clinicians and evolving into academic coordinators employed by Ukwanda Centre for Rural Health. EdP has more recently been involved in the establishment of a new clinical training platform in Northern Cape Province from 2018. JvN was not involved in the RCS in any way and therefore brings an external perspective to interpreting and presenting the data.

Figure 1: Distribution of Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences academic programs working across the Rural Clinical School platform in 201740.

Figure 1: Distribution of Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences academic programs working across the Rural Clinical School platform in 201740.

Table 1: Total number of undergraduate final-year students who rotated through the Rural Clinical School, Worcester campus, 2011–2016

Methods

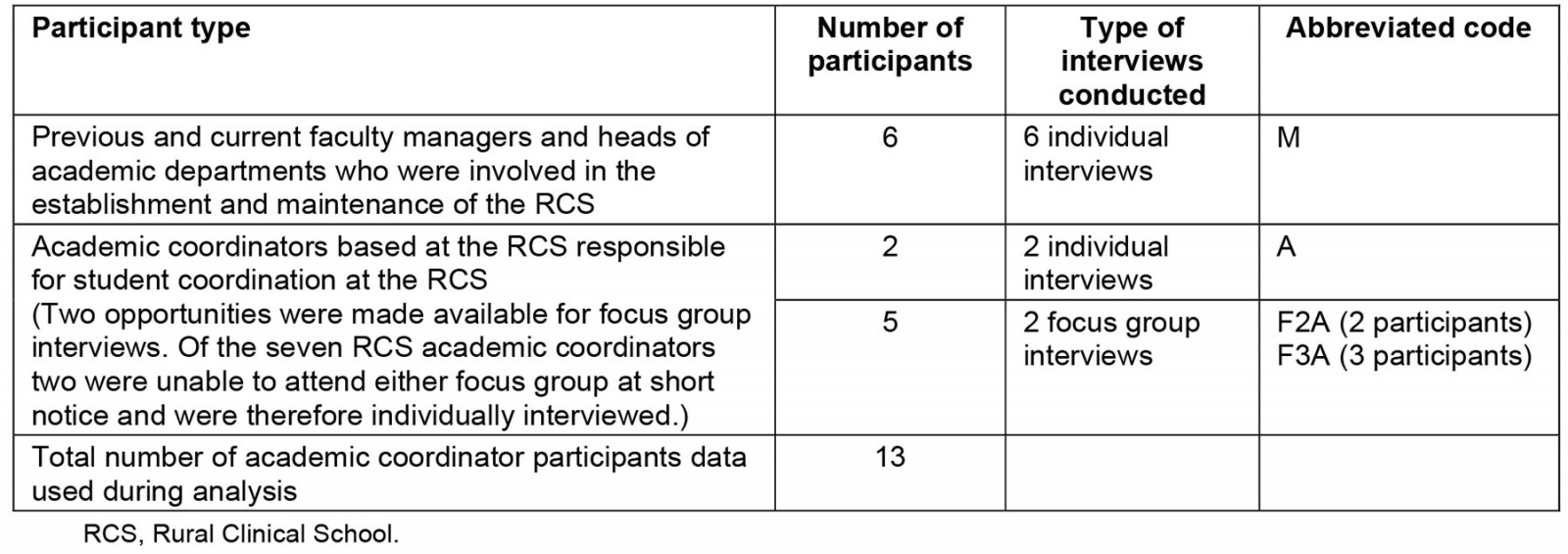

This qualitative research follows an interpretivist design and is part of a larger study that was conducted in 2017 exploring the 17-year history of Ukwanda Centre for Rural Health, including the development of the RCS. The study included a retrospective qualitative review of 17 years of documentation as well as individual and focus group interviews conducted with faculty role players to provide historical insight into the development of Ukwanda and the RCS training platform41. Table 2 provides a breakdown of the participant population, data collection methods and abbreviation codes used in the Results section.

Participants of the larger study exploring the history of Ukwanda were purposively selected using a network analysis to provide historical insight into the development of Ukwanda and the RCS training platform as well as individuals actively involved with the Centre and School at the time of the study. Nineteen faculty role players were identified during this process, of which 13 were responsible for academic coordination at either Tygerberg or Worcester (see Table 2). Written consent was obtained by all participants after full disclosure that despite every effort to maintain confidentiality during the analysis and writing of any reports or article, there could be a risk that quotes from some respondents may be recognised because of the nature and proximity of the teams involved in the development of the RCS. Semi-structured interviews were conducted by JM (principal investigator of the larger study). These interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, translated where necessary and inductively analysed using ATLAS.ti v8.4.26.0 for Windows (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development; https://atlasti.com) by JM, whose extensive involvement with the data from collection to analysis allowed for immersion in the content. Two international experts in the field of rural health professions education were involved in critical reflection sessions with JM during the analysis process and writing up of the findings. For the purposes of this article, codes relating to academic coordinators’ experiences and perceptions were identified and cohesively combined to explore themes related to their experiences during the development of the RCS. Triangulation of data collected from various role players involved in the development of the RCS was done to provide a rich description of the history42.

All data are stored in a password-protected folder on the institutional cloud network accessible only to JM.

Table 2: Research participants, types and numbers of interviews conducted

Ethics approval

Permission to conduct the study was granted by the Institutional Research Committee and ethics approval was obtained by the Health Research Ethics Committee at Stellenbosch University prior to the commencement of data collection (HREC N17/02/022).

Results

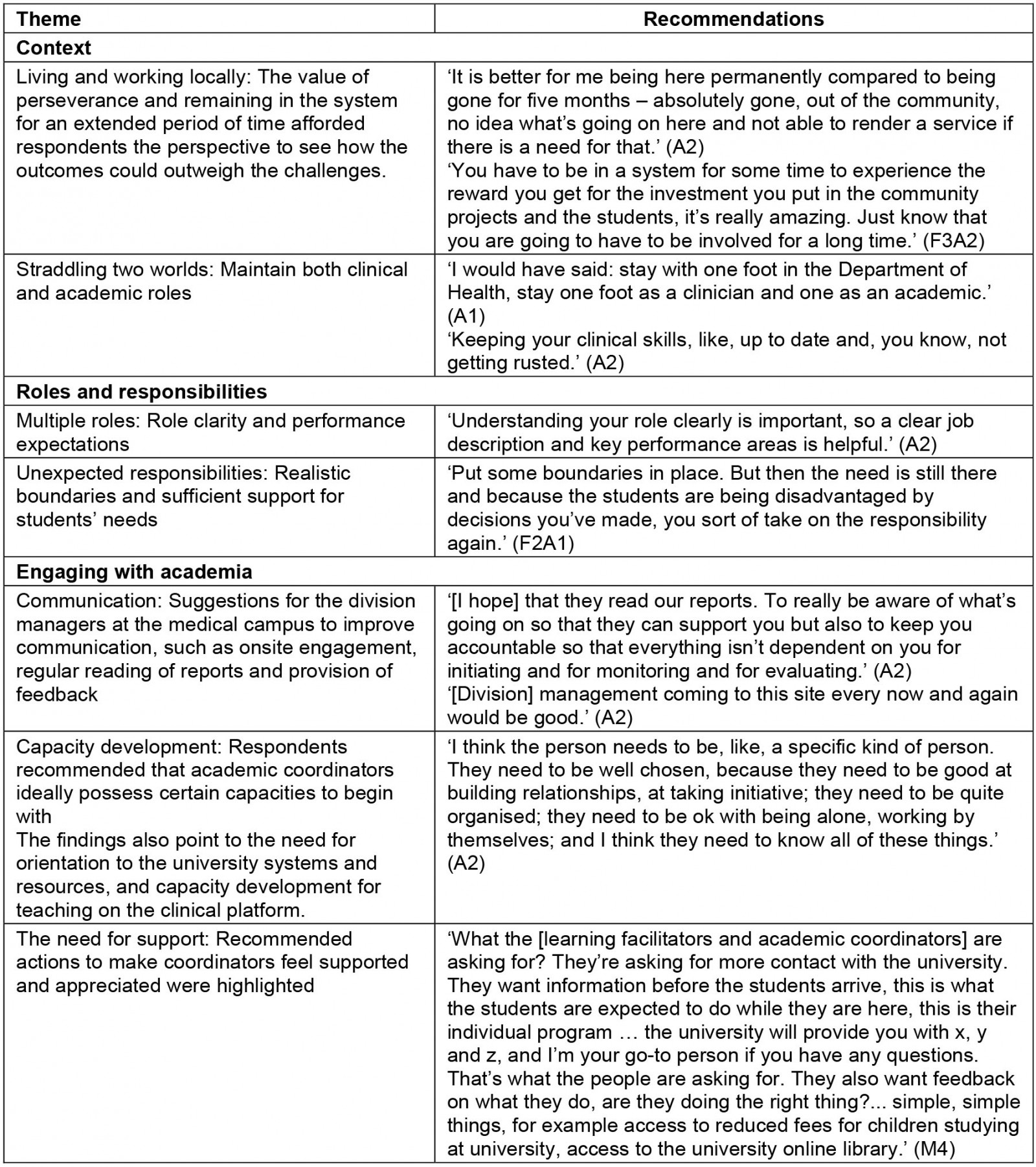

Three overarching themes were constructed from the data during analysis namely: context; roles and responsibilities, and academic support, which are represented in Appendix I with their relevant subthemes and corresponding findings. Recommendations are considered as an additional theme, and as the main focus of this article are presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Recommendations made by participants

Discussion

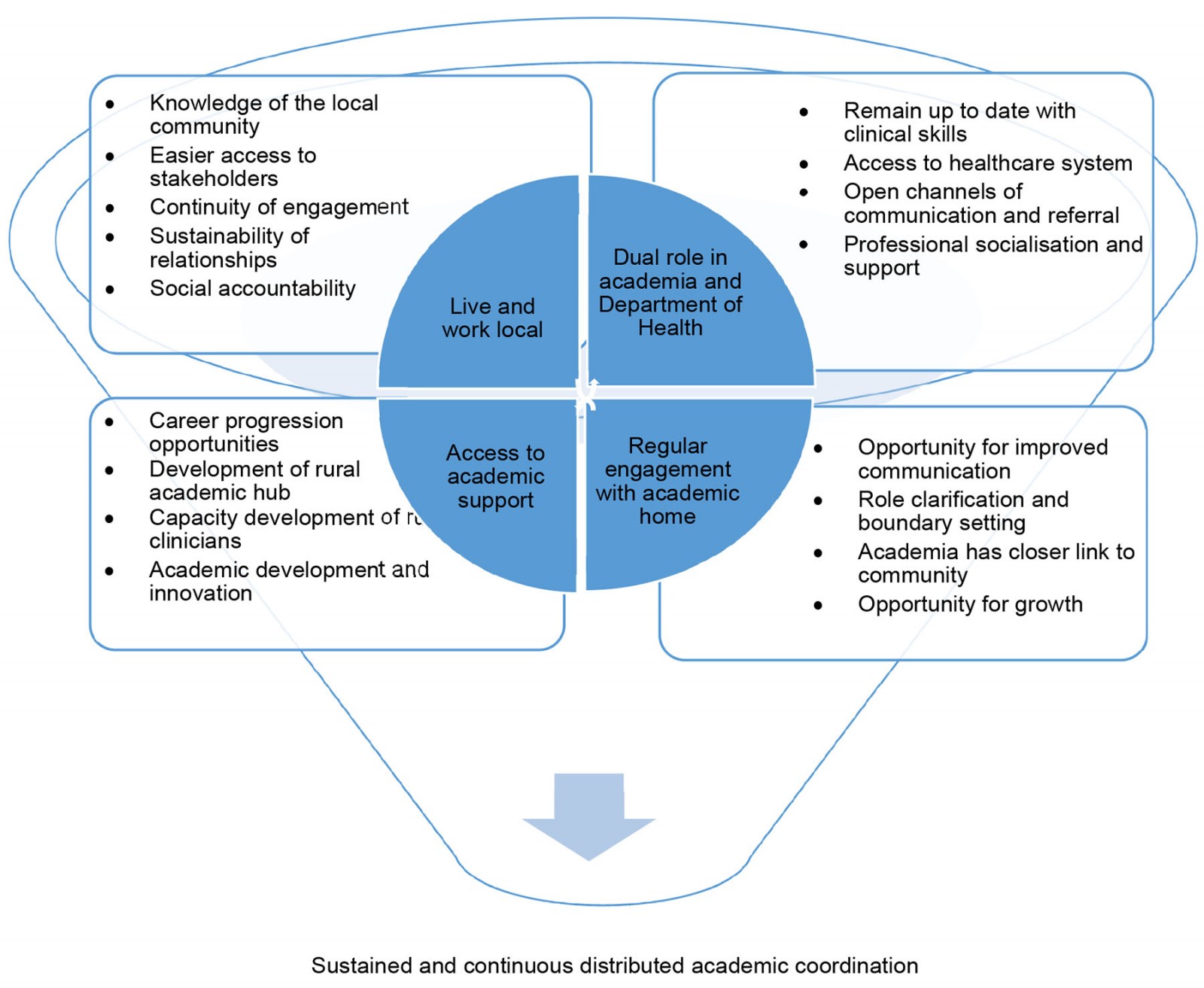

The establishment of a distributed clinical training site for undergraduate students is complex and presents both benefits and challenges that can enhance or impede health professions education. Coordination and training of students on the DTP require capital for physical and human resources, capacity building for clinical educators, distinct differentiation of roles and responsibilities of personnel (clinician v coordinator), and bridging the distance between the DTP and the academic institution33,43,44. These challenges can be mitigated by improving organisational governance and communication between platform and institution44 by recruiting academic coordinators32,33. The aim of exploring the fluid and evolving roles of academic coordinators was to determine what structures and support may best equip onsite academic coordinators as the DTP in South Africa expands. The experiences of the academic coordinators at the RCS resonate with some of the same barriers and disconnects identified in previous studies33,45. Figure 2 provides a summary of the perceived value of considering context, roles and responsibilities, regular engagement and academic opportunity of coordinators on the DTP. These suggestions are explored in light of the existing literature.

Figure 2: Aspects to consider in the support of an academic coordinator on the distributed training platform and what affordances each of these offers.

Figure 2: Aspects to consider in the support of an academic coordinator on the distributed training platform and what affordances each of these offers.

Context (living and working locally; straddling two worlds)

The interdependency of the health and higher education systems is a core tenet of the Lancet Commission’s guidelines on education of health professionals for the 21st century13 and of the conceptual framework adopted by the ASSAf panel in contextualising this transformation in South Africa12. The relationship between these is also fundamental to many of the recommendations for successful distributed training sites44. At the local level of the rural clinical training site, the academic coordinator/clinical supervisor role appears to stand precisely at the juncture of these two systems.

The findings presented above show that rural placement of coordinators enabled a greater ease of access in engaging potential clinical sites and establishing rules of engagement between the site, the university and the students, and orienting students to the sites. This speaks to institutional support and alignment with the needs of already overburdened clinical staff working in healthcare facilities. The practice of appointing rural coordinators is in line with existing literature related to nursing and occupational academic coordinators32,33. The positive findings related to context stood in contrast to academic coordinators residing outside distributed training sites who experienced challenges in establishing a similar level of rapport with the local community and healthcare system. Furthermore, the continued presence of rural-based coordinators also seemed to affect the perceived social accountability of the university in terms of maintaining continuity of services in the absence of the students. The importance of this is highlighted by the call for socially accountable university–community partnerships46,47. Allowing a fluid role for academic coordinators to work within the healthcare system where the students are training has the potential to benefit not only the students but human resources for health, as well as alleviate the expressed need academic coordinators have in remaining connected to their clinical work.

Health professions students’ success depends on relationships with peers, teachers and the community15,46. A breakdown in any of these relationships will impair student success9. In particular to the student–teacher relationship, placement of permanent staff in remote areas provides opportunity for role modelling and mentorship47, which plays a crucial role in inspiring junior doctors to practise in rural areas48. The continuity of engagement between the academic coordinator and student may also facilitate the development of what Walters et al (2021) refer to as clinical courage in rural areas, which is heavily dependent on interpersonal relationships and relationships with the local community and healthcare system, which can be fostered by academic coordinators who are local to the training site49. Many of the onsite clinicians recruited by the faculty as academic coordinators left their clinical positions in practice and took up full- or part-time employment with the university. This affected the academic coordinators' access to patients, multidisciplinary health care teams as well as opportunities to maintain their clinical skills. The resultant professional isolation academic coordinators experience as a result may impede the maintenance of the relationships required for the development of clinical courage49.

It is clear from our findings that there is similarity to the De Villiers et al (2017) scoping review in that there is an expressed need for capacity building of clinical supervisors in health professions education10. In this study, however, clinicians who exited the clinical healthcare system to become academic coordinators on the DTP indicated their desire for continued professional development to maintain clinical skills competencies. The need for capacity building on the DTP also needs to extend to the processes of community engagement and the maintaining of profession-specific clinical skills9. The distancing of these clinicians from their professional practice to accommodate student training and support results in a sort of no-man's-land where coordinators felt removed from their clinician peers working in the health system as well as their academic colleagues based on the faculty campus. Reconsidering the space academic coordinators find themselves in may be an important contribution to enabling and supporting them as the DTP grows. Cohesive teamwork among clinicians within the clinical site and sustained relationships of trust with community stakeholders is an imperative part of health professions education on the DTP18. The results of this study indicate that this is made possible if the academic coordinator remains linked to the healthcare system.

Roles and responsibilities (innovation and collaboration; multiple roles; unexpected responsibilities)

Clinicians who become involved in student supervision are often new to academia, with limited to no experience or training in health professions education23. Additionally, clinicians reportedly feel uncertain and insecure in their roles as teachers, especially at the initial stages of student engagement, as most clinicians do not intentionally pursue teaching roles until students are allocated to the facilities where they work23,50. The findings of this study demonstrate that while capacity-building workshops and short courses on clinical teaching offered by the university might be helpful in building teaching capacity, translation of this theory in the academic coordinators context requires onsite support and guidance. The establishment of a community of practice with remote support and training is recommended in preparing distributed training educators, but how this is enabled requires further exploration18,24,31. It would benefit both institution and individual if academic coordinators were supported to develop a strong teacher identity over time and a sustained commitment to the responsibility of training future colleagues23 while potentially pursuing an interest in an academic career.

Health professionals working as clinicians based in rural or remote contexts noted a blurring of boundaries, as well as expectations outside of their scope of practice, which increases their workload51. Similarly, the findings of this study suggest that academic coordinators’ responsibility to academia, the health service, the community and the student results in a blurring of boundaries and a subsequent non-specificity in their scope of work. Academic coordinators’ time and capacity was spread thin between students, academic programs and the local community. Without the support of additional personnel at the distributed site, academic coordinators face a risk of burn-out and resignation. One would expect a high turnover rate of personnel in this environment, which has been identified in literature relating to physiotherapy academic coordinators and compromises the momentum and sustainability of the DTP43,45, but that was not the case in this study. Some respondents, although overwhelmed and tired, driven by a strong sense of responsibility, seemed drawn to the variability and challenge of the work, which has been identified as a favourable attribute when recruiting academic coordinators who are most likely to be successful on the DTP in a study by Silberman (2020)43.

A possible solution to this risk of overburdening the academic coordinator is to adopt a supervised peer learning approach, where students support each other’s learning, and the supervisor offers guidance to multiple students (as teacher, facilitator, stimulator and/or team player) in a simultaneous, integrated process of learning and patient care within a broader ward culture of learning21. This is possible when a good relationship with other health professionals on site and a shared agreement with health services management is maintained45. In this scenario, the academic coordinator need not be split between students’ learning and their own skill development and maintenance.

Regular engagement (resource challenges; communication; capacity development; need for support)

On-site visits by faculty staff for the development and maintenance of relationships with academic coordinators appear to be pivotal for inclusive engagement to ameliorate any feelings of isolation or exclusion from the facility. A recent study by Greco et al (2021) echoes this sentiment52. To mitigate the expenses of multiple disciplines doing onsite visits, McGrew et al (2008) suggest adopting ‘circuit riders’ who visit sites on a rotational basis so that academic staff have the opportunity to interact with staff, students and stakeholders during a rotation51. These onsite visits provide an opportunity to recognise and provide the necessary support in terms of human resources challenges, academic capacity development, juggling multiple line managers, communication breakdowns, administrative and even psychological support to the coordinators. The need for adequate and reciprocal communication between onsite academic coordinators and the academic department at the faculty was expressed, and from the findings it is suggested that this would ameliorate the challenges coordinators face. A possible solution would be online support systems, such as regular online platform meetings or peer support groups, which could be implemented in order to improve support for academic coordinators on the DTP. Effective communication and ultimate development of relationships have the potential to provide a feeling of equal partnership and influence to the various parties involved52-54.

Growth of coordinators into academics who can contribute to the field where they work and live could have important consequences, not just for their career trajectories; it will also serve as an incentive to remain on the distributed platform and build capacity at these sites55. In a no-man’s-land between clinician and academic where the prospects of career mobility are unclear, health professions education and mentorship beyond clinical and supervisory skills may empower and enable academic coordinators to consider a career as an academic. Research into the academic career trajectories of faculty-employed academic coordinators in physiotherapy showed that clinically based academic coordinators are far less likely to advance to permanent academic employment or advance along tenure track in relation to academic coordinators who are based at the faculty39. Potential reasons for this include there not being an academic coordinator assessment survey based on the unique roles that these faculty staff fulfil39. Providing an opportunity for academic development and promotion for academic coordinators on the distributed platform has the potential to improve job satisfaction and subsequent sustained coordination of a successful learning model.

Formalised governance structures for monitoring and reporting would enable continued engagement, identification of challenges and facilitators, a redress of barriers and accountability by academic institutions. This would, however, require open communication channels, which should be encouraged and protected, as highlighted by the SUCCEED framework54,56. There are opportunities for a streamlined and defined governance structure that clearly maps out the synergies and overlaps that would ensure migration towards relationship development, support, and the ownership of a shared vision and process25.

This discussion of findings offers important considerations for planning, preparing and maintaining new distributed training sites, especially as it relates to the evolution and employment of academic coordinators on the platform, as encapsulated in Figure 2. These insights are especially important in light of the current expansion of health professions training, for which strategies are needed to attract and retain clinician–academics in remote locations.

Limitations and recommendations

The aim of this article is not to generalise, but to increase awareness of the complexity of establishing and sustaining rural distributed training sites, particularly with respect to the vital role and challenges academic coordinators play in this process. Although the findings of this study are bound to academic coordinators from RCS in the Western Cape, South Africa, and therefore consist of a small population, the participants are from five different health professions programs and have been involved with students placed at multiple sites over a number of years (Table 1).

We acknowledge that experiences some years later at RCS as well as at newly established sites could be very different from what they were when the data were collected in 2017. A follow-up study to explore and evaluate the strategies put in place to remediate and improve relationships, support and capacity at these sites may prove beneficial. The publication of the SUCCEED framework in 2020 and the process of its development at Stellenbosch University provide an opportunity to explore to what extent the framework is currently being considered at RCS and other newly established DTPs. Exploring the experiences of academic coordinators involved in the newly established Upington training platform in the Northern Cape Province, 800 km away from the faculty home, is recommended and could offer valuable insights into the lessons learnt since the development of RCS and the SUCCEED framework.

There are many lessons to be learnt from the experiences of academic coordinators whose roles have evolved and transitioned at such a fast pace, testing their own perseverance, innovativeness, altruism and purpose.

Conclusion

Insights from a range of academic coordinator experiences of living and training students on a DTP highlight the academic, professional identity and role clarification challenges of being remote faculty staff. Insights into the value of living and working local to the distributed training site while fulfilling roles in both academic and clinical environments are explored. We provide recommendations on how health science faculties can prepare someone for the unique and critical role of distributed academic coordinator and how to provide them with adequate support and recognition. The potential value to both the individual coordinator and the academic institution when the recommendations are put into place are crucial to the sustainability of what has already been shown to be a successful model of training internationally. Recommendations derived from a low–middle income context related to remote site communication, development of formal governance structures, clear role definition as well as promotion and retention strategies could be adopted, adapted and innovated to help meet the needs of distributed academic coordinators in other contexts across the globe.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sandisiwe Matyesini for her work in critically reviewing the article and her contribution to logic and flow, and Amanda Msindwana for her objective view of the data interpretation and reflective sessions to enhance the trustworthiness of data presentation.

Funding

The data used for the purposes of this article were collected as part of a larger study funded by Ukwanda Centre for Rural Health, Stellenbosch University.