Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, childhood obesity is one of the most serious public health challenges of the 21st century1; prevalence is rising quickly, and it has well known negative impacts on affected children’s physical and mental health2. Obese children will most often carry this problem into adulthood and develop non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular problems3,4.

Research shows that both child and adult overweight and obesity are more prevalent in rural than in urban areas5-12. A variety of contextual (relating to characteristics of a place) and compositional (relating to characteristics of residents) factors have been put forward to explain the urban–rural differences in weight status. These commonly include aspects related to dietary intake, physical activity, geographical distances and socioeconomic status. Some studies assume that the generally lower socioeconomic status of rural residents can explain geographical differences in weight status10,13. Others have found that rurality increases the risk of being overweight or obese independently of such compositional factors, and calls have been made for context-specific strategies to tackle the problem in rural areas7,13.

Over the past decade or so, several national guidelines have been established for the Norwegian health sector to meet the challenges of overweight and obesity, and ensure professionalism and standardisation of health services14,15. These new guidelines have occurred at the same time as, or due to, the introduction of management principles such as New Public Management (NPM), which requires that procedures, goals and goal achievement are standardised and quantifiable, and they are subject to controls to ensure equal access to treatment options throughout the country16.

NPM is a general theory of how the public sector can be improved by importing business concepts, techniques and values, and it includes practices that are measurable, specialised, and where hierarchical relations are the principal coordination device17. Healthcare providers must deliver on efficiency and quality17 with a focus on costs reduction and increased efficiency in the Norwegian health sector. Working with standardisation of services has been a means for becoming more efficient and enabling equal access to the treatment options, regardless of where in Norway people live18.

The standardised and fragmented discourse in NPM makes certain aspects of work invisible19. What cannot be measured, such as coordination and collaboration between services and care-related tasks that increase the quality of life, becomes invisible and loses its value. An example of this is that different health and education services around a child are poorly coordinated, which can lead to fragmented care where professional caregivers, such as teachers, public health nurses and general practitioners, work in silos.

In Norway, the NPM entered into the area of child overweight and obesity in 2010 with The National Guidelines for the Standardized Measurement of Height and Weight14 and The National Guidelines for the Prevention, Identification, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Children and Adolescents15. These guidelines build on a screening of body mass index (BMI), with 25 kg/m² as the starting point for intervention14. Public health nurses have shown scepticism towards this cut-off level, as they experience it as too low in some cases20.

While one of the motivations for the latter standard was to implement a more contextually based approach15, both sets of national guidelines build on a ‘one size fits all’ approach. This challenges the need for a more contextually based approach as concluded by Krokstad et al7, who suggest that preventive strategies should focus on counteracting the obesity epidemic by acknowledging geographical differences.

Even if the municipalities in Norway vary widely in terms of geography, demography and organisation, they all must adhere to the same national guidelines and laws. This applies to the Public Health Act (2011) which came into effect in 2012 and is one of the most important policy instruments for dealing with environmental, social and structural factors that affect public health in Norway21. The main responsibility for implementing public health measures is placed at regional and local levels, and it involves all sectors in the municipalities. The extreme variation in size, geography, competence and resources among the municipalities in Norway results in different ways of operationalising The Public Health Act. In 2016 the Office of the Auditor General concluded in its investigation that the lack of anchoring public health work across sectors in a municipality is the largest barrier to success in public health work22.

That the main responsibility for implementing the national guidelines is placed at regional and local levels also applies to treatment of overweight and obesity among children20. Public health nurses are recognised as a vital resource in efforts to decrease childhood overweight and obesity because they have great opportunity to interact with children and young people and their parents/guardians23,24. They are responsible for measuring the height and weight in children and adolescents, and initiate treatment when necessary. The protocol for Norwegian nurses is, among other things, to refer children and youth with a BMI of 25–30 to secondary health care14,15. In addition, they have a (standardised) conversation, often by phone, about the issue and possible intervention with the overweight child or adolescent and her or his parents or guardians20.

There is a risk that NPM guidelines complicate the prevention and treatment of rural overweight and obesity because they disregard the specific causes – as well as opportunities – inherent to the rural context. The literature suggests that it is important to learn more about how public health nurses implement national guidelines into practice, but there is limited knowledge about how public health nurses in rural areas perceive national guidelines.

The introduction of the new guidelines in 2010 resulted in negative reactions from the health personnel that were assigned to carry out the weighings20, mostly because no extra resources were allocated for this new work task. Public health nurses questioned the resources available and whether they had the skills to develop and perform all the tasks the guidelines assigned to them. Overweight and obesity in adolescence often mirror complex problems and might demand multidisciplinary follow-up20. This article focuses on public health nurses’ work with overweight and obesity, but these professionals must cooperate with other stakeholders, such as GPs, physical therapists, other health services and parents. Public health nurses report a lack of collaborating partners, both to ensure competent knowledge to help overweight children (which they feel that public health nurses do not have themselves) and for referral options18,20. Therefore, interviews were carried out with other cooperating stakeholders to try to get a better understanding of the public health nurses’ situation.

The focus of this article is the extent to which public health nurses in rural areas of Norway feel equipped to tackle the overweight and obesity epidemic within the framework of the two sets of national guidelines, concentrating on available resources, inter-agency cooperation and the rural context. The data were gathered by a questionnaire and interviews with public health nurses and other municipal stakeholders responsible for the prevention and treatment of overweight among elementary school children in rural areas in Norway.

Methods

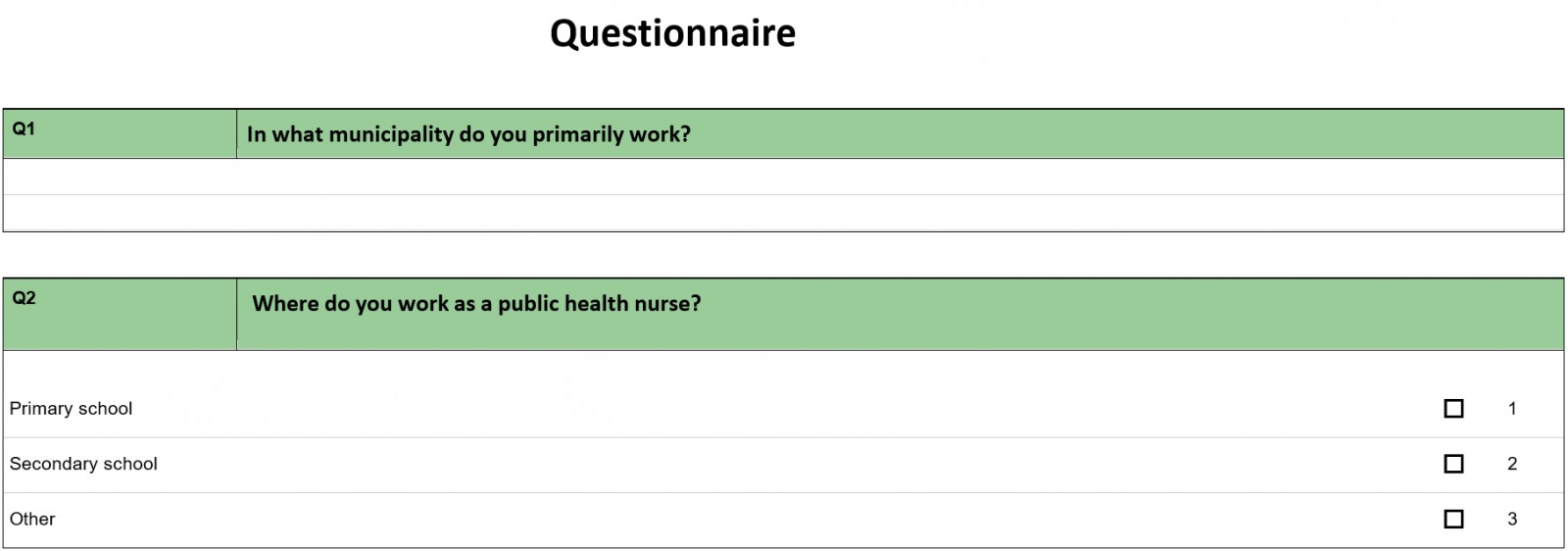

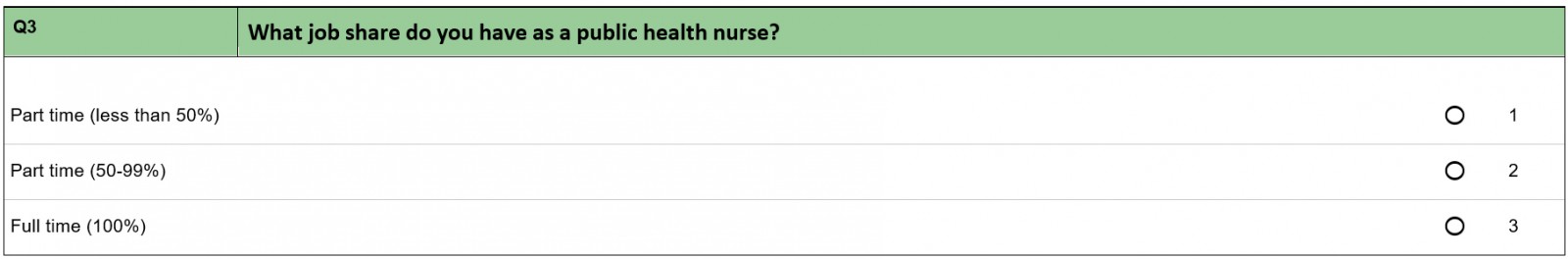

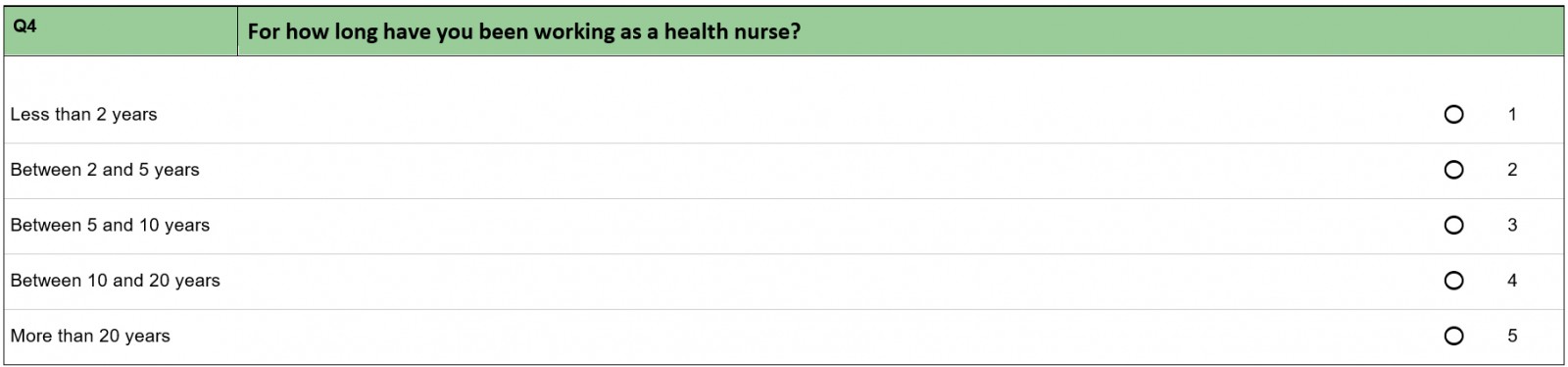

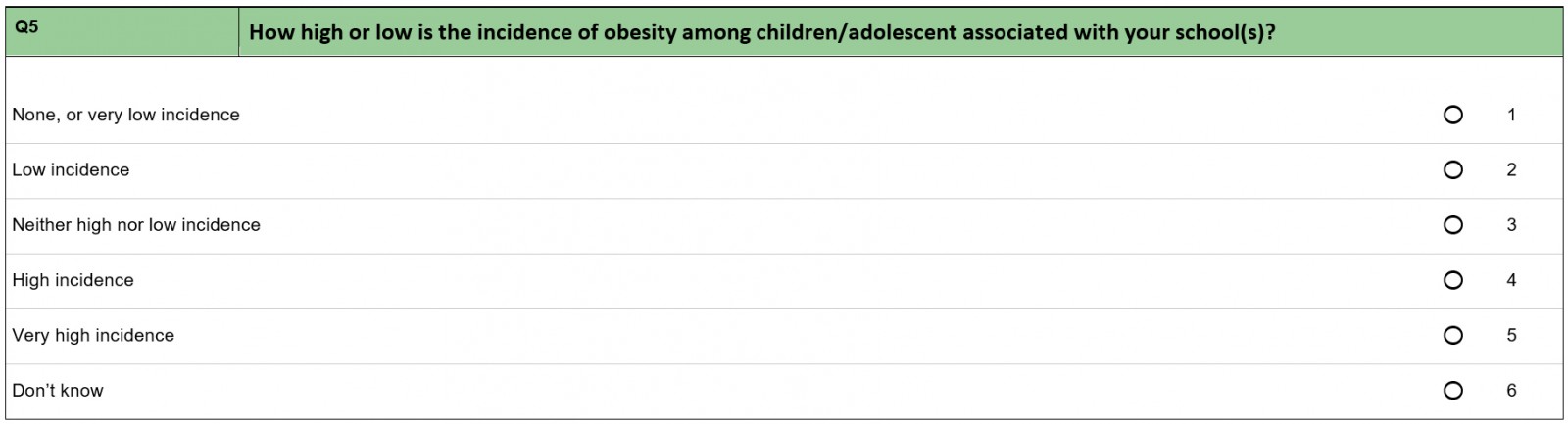

In this study, two approaches were used to gather data. The first approach was a structured questionnaire (Appendix A) that was conducted among members of the National Group of Public Health Nurses in Central Norway (Trøndelag County), which represents a high proportion of the public health nurses who work with children in primary and secondary schools in this area of Norway. The questionnaire covered various topics related to working with overweight and obese children. An area was defined as rural if the municipality met either of the following criteria:

- scored 4–6 on Statistics Norway’s centrality classification, which ranks municipalities on a rural–urban scale from 1 (the most central municipalities) to 6 (the least central municipalities) based on travel time to workplaces and service functions25

- had more than 30% of their population living in sparsely populated areas26.

The main goal of the questionnaire was to gain insight into a range of attitudes and reflections on the ways in which school nurses work with the guidelines.

Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted, informed by the questionnaire, with key informants, such as public health nurses, doctors, principals, physiotherapists and ergotherapists, who work with overweight and obese children (Appendix B). The project was funded by the Regional Research Funds in Central Norway, and the informants were purposively selected from two rural municipalities of this region, one by the coast and one inland. The informants were contacted via the local public health coordinators. A total of 25 informants were interviewed, both individually and in groups; none were interviewed twice. Semi-structured individual interviews give researchers opportunity to follow up on what is important for each informant. The advantage of focus group interviews is that informants engage in dialogue with each other, which can offer a broader understanding of the interaction between stakeholders and stimulate further reflections among informants27. Even though only the interviews with the public health nurses were analysed for this article, the interviews with other stakeholders offer background information about the situation of overweight children in these two municipalities. Four individual interviews and four focus group interviews were carried out in this study, a total of eight interview settings. The interviews, which were audio-recorded and transcribed, were conducted at the informants’ workplace, each interview lasting 1–2 hours.

The analysis process applied was inspired by the work of Tjora28 and the stepwise deductive inductive strategy that aims at developing codes, categories and concepts as a basis for reaching new understandings of the topic in question. The transcribed interviews were analysed in two steps. First, an overall process of coding based on the themes in the interview guide was conducted. The transcriptions were read several times, and words and sequences with a relevant content were marked. The second level of analysis involved a more thorough coding of the parts of the interviews that connected to the standardised guidelines. We inductively collected the codes that had a mutual thematic connection29. The coding and the grouping of codes28,29 led to a closer focus on the three categories.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (approval number 927132).

Results

Based on analysis of the questionnaire answers from the 57 public health nurses (40 of them working in what we define as rural municipalities), and the qualitative interviews, three categories were identified: competence and resources, lack of interdisciplinary cooperation, and the importance of seeing a child in context.

Competence and resources

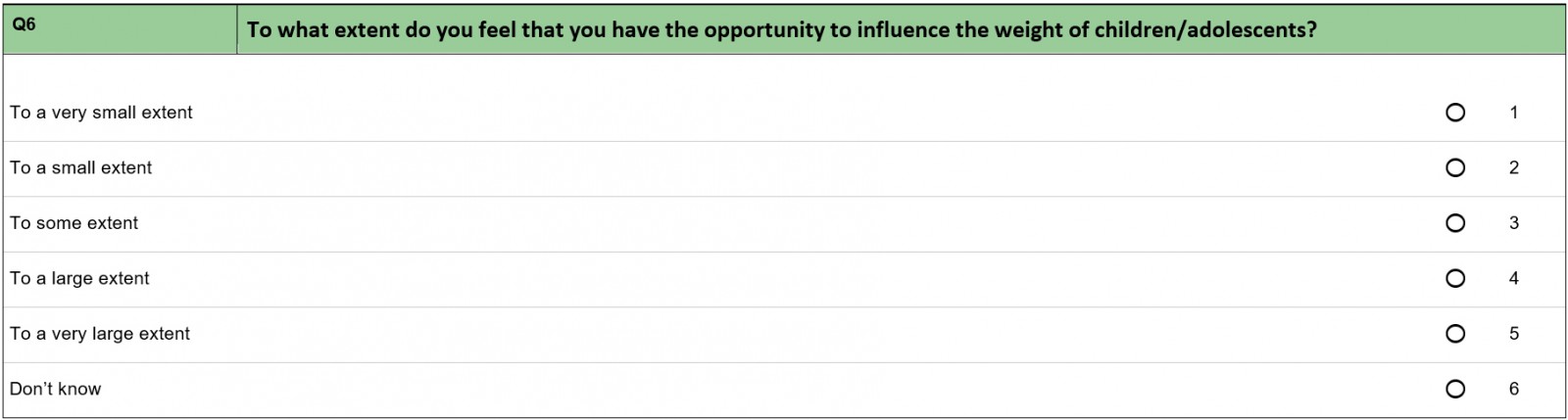

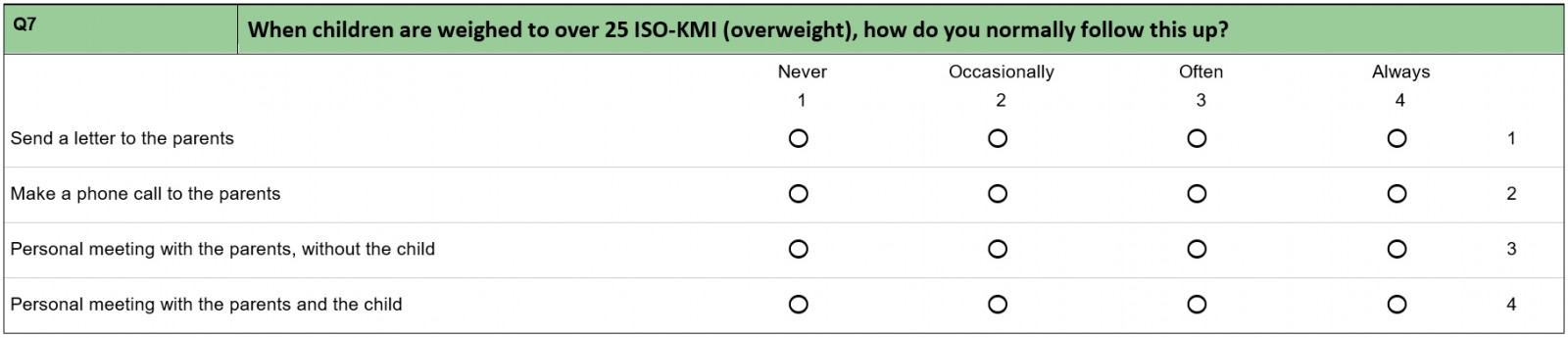

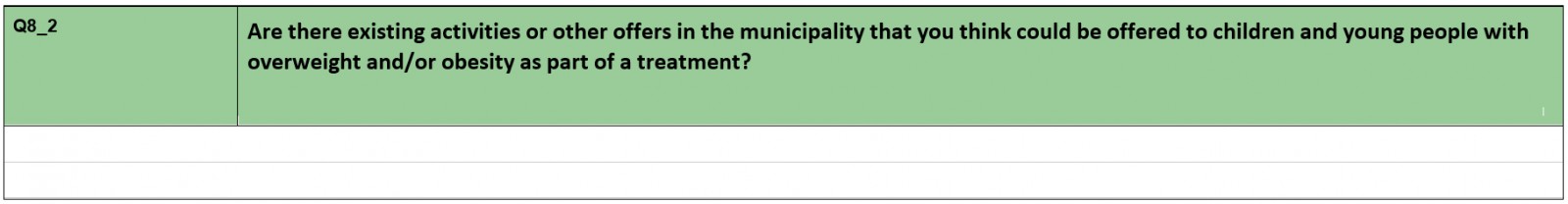

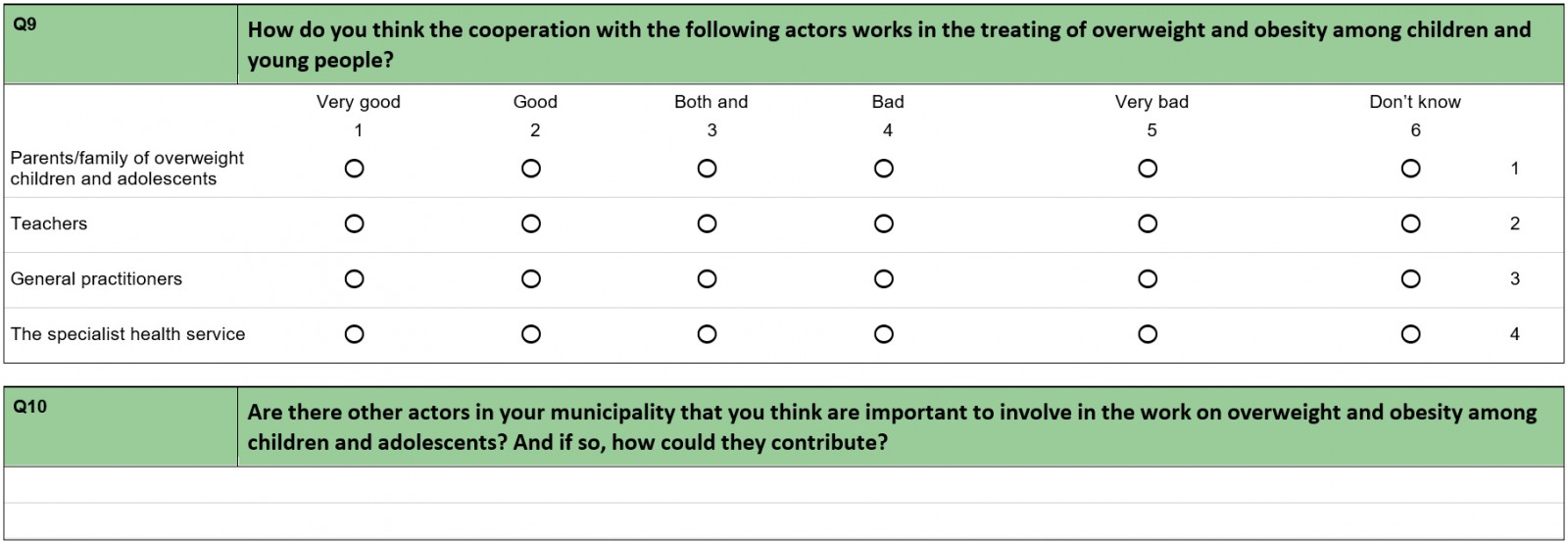

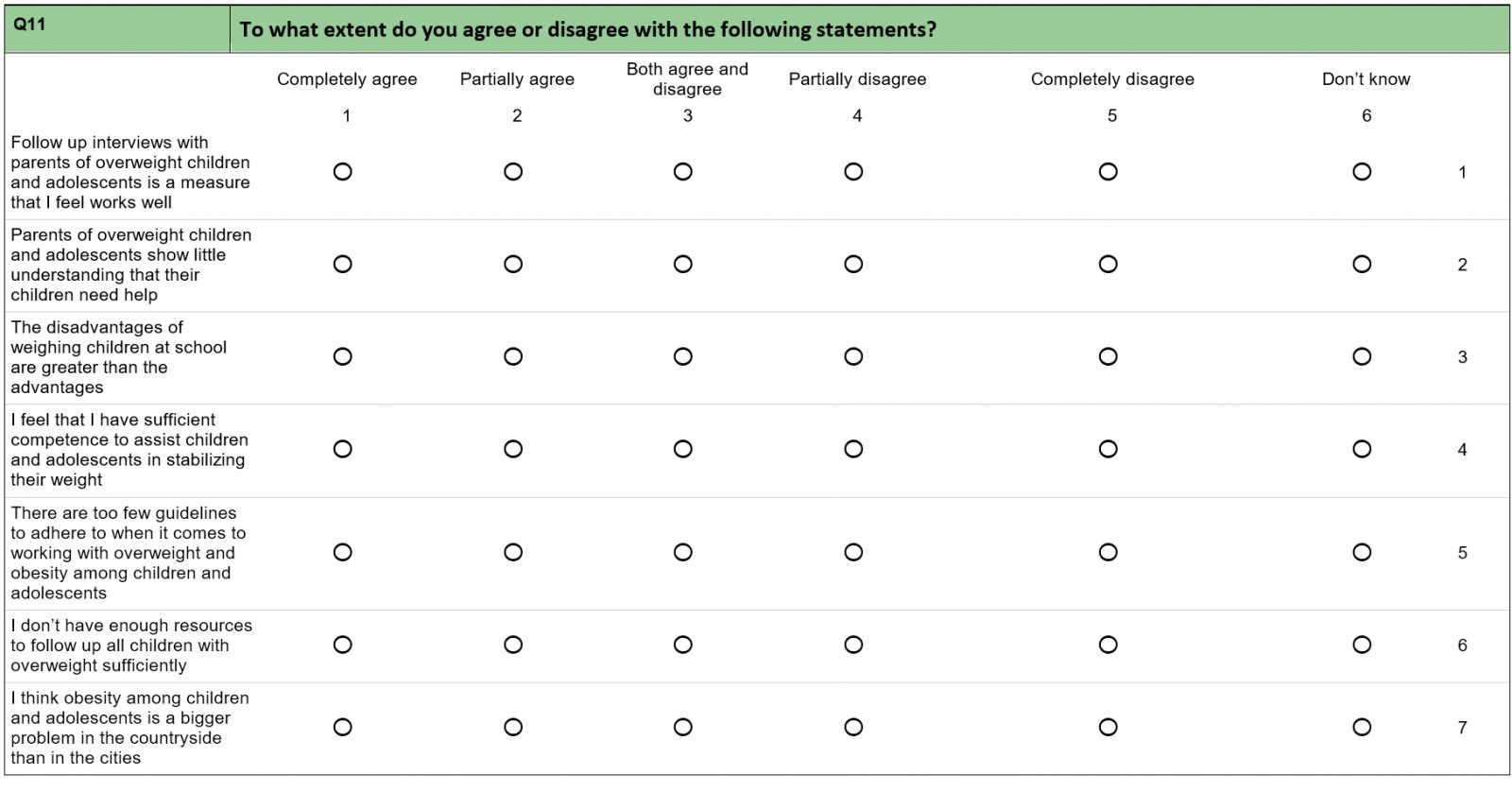

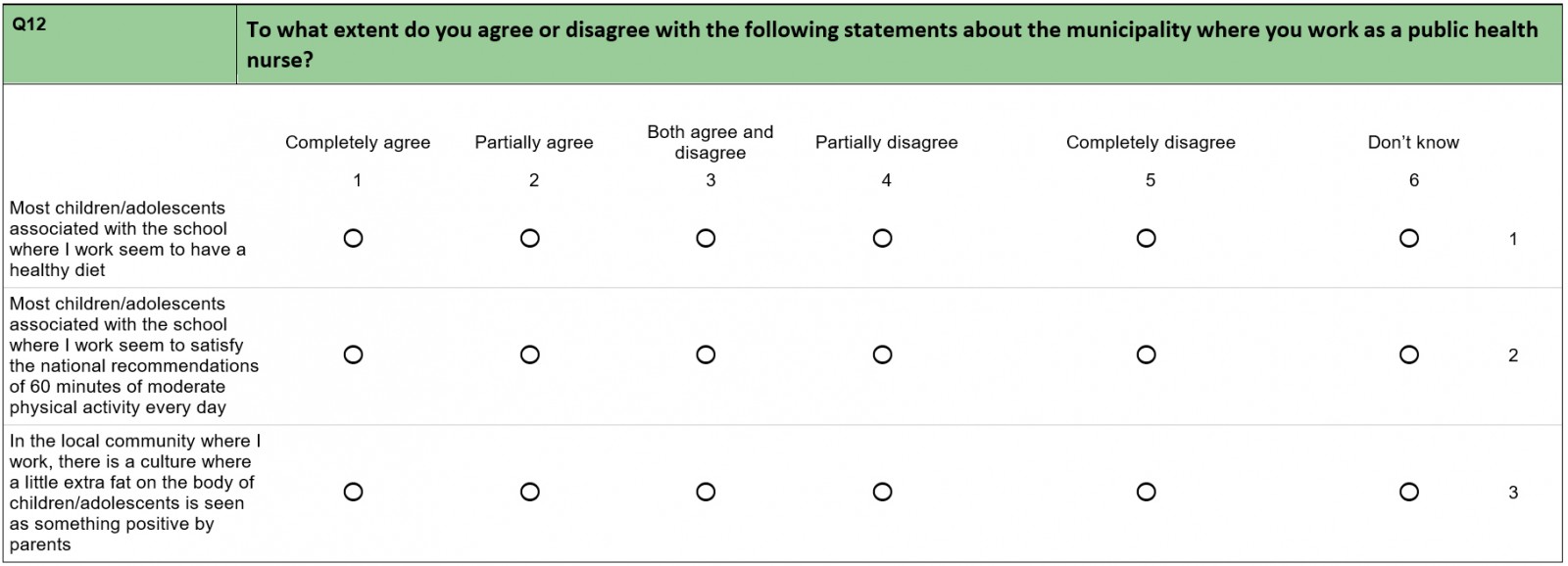

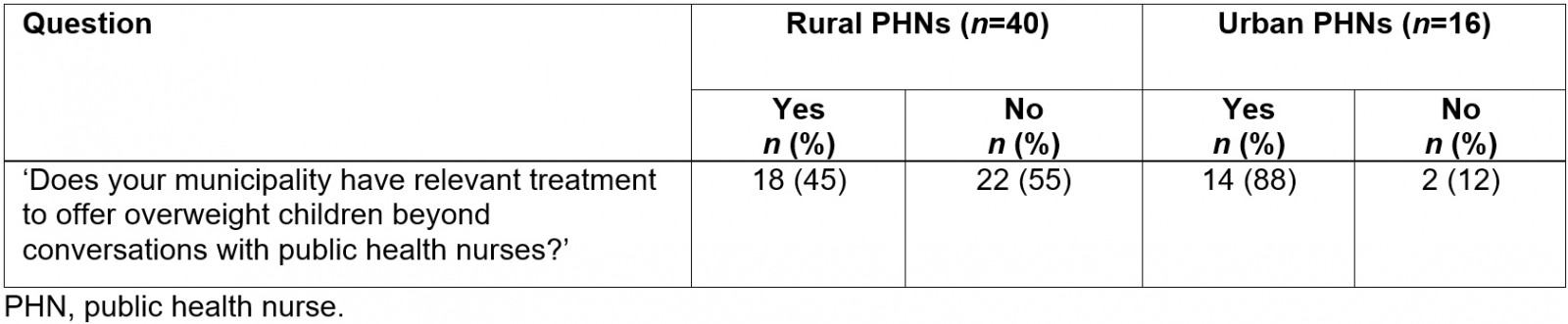

When The National Guidelines for the Standardized Measurement of Height and Weight were introduced in 2010, public health nurses who had to do the weighing expressed frustration about the lack of resources for the new tasks14,15. Three questions in the questionnaire focused on resources and competence. Comparing the public health nurses working with children in rural and urban areas revealed a key difference concerning treatment for overweight children.

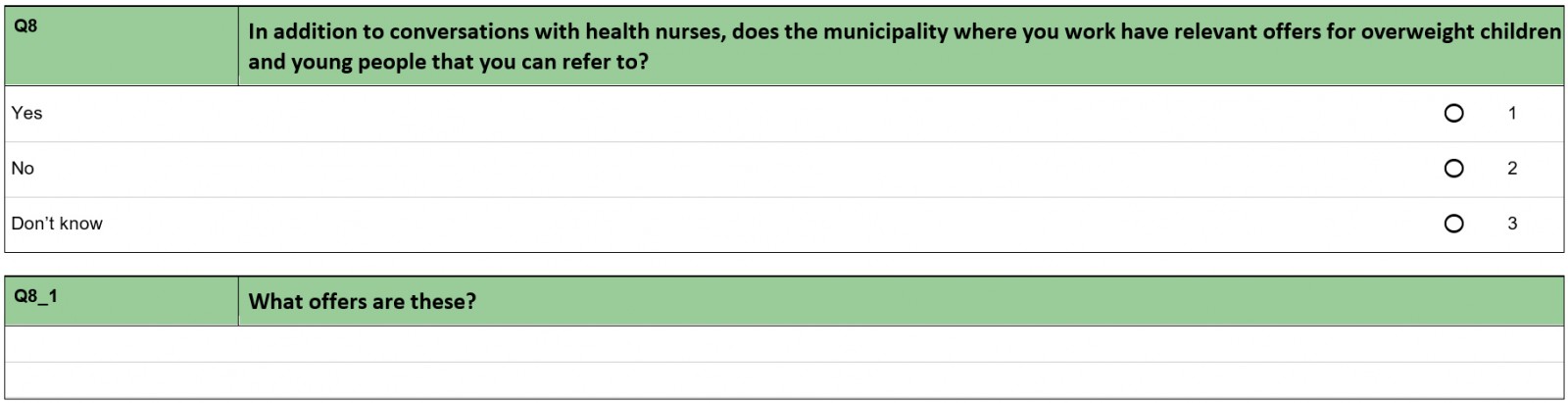

Table 1 shows that less than half of the rural public health nurses reported that their municipality had treatment options for an overweight or obese child beyond the standardised conversation with public health nurses. Almost all of the urban public health nurses, on the other hand, reported that they did have relevant treatment to offer. This shows a large discrepancy in the public health nurses’ assessment of relevant treatment options their municipality can offer overweight children.

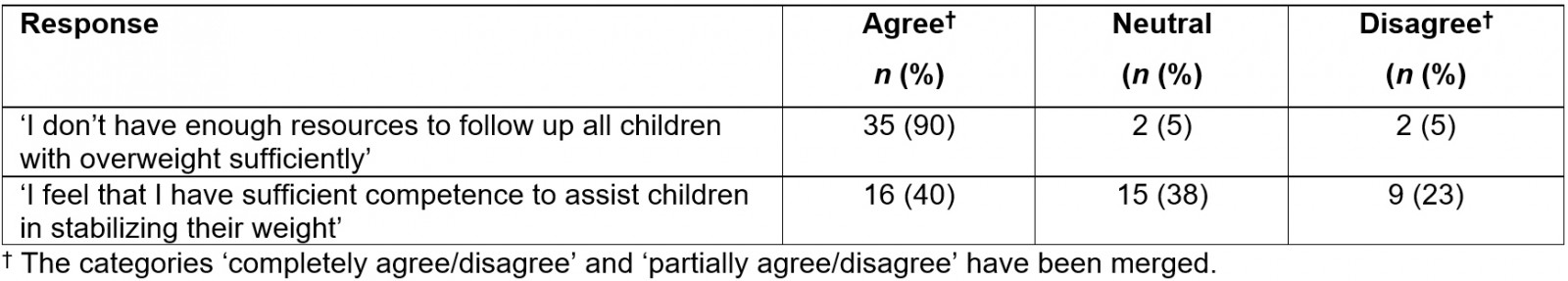

Several of the public health nurses answered that they felt a lack in resources to follow up all the overweight children, and that they did not have the sufficient competence to assist children in stabilising their weight. The resources referred to include a lack of time, employees, economic resources and other resources.

This concern also arose in the qualitative interviews with the informants. The interviews showed that the perceived lack of offers, solutions and resources caused a sense that the weighing was unethical.

Many of the public health nurses avoid the weighing because they don't have any tools if they uncover a problem. And therefore, they think of it as unethical. Just to point out [they are] overweight, and not be able to offer any solutions for how to handle it. (Health coordinator, municipality 1)

A consequence of this is that the public health nurses merely tell the child and the parents that the child is overweight without being able to offer a solution. Some public health nurses find this rather unethical and therefore they avoid weighing the children. The situation was exacerbated by the fact that rural public health nurses often work alone and have no one to share these thoughts with. The rural public health nurses pointed out a need to look at the situations of the overweight children from different perspectives. Several public health nurses suggested a stronger focus on interdisciplinary cooperation as a solution to these challenges.

Table 1: Treatment for overweight children by public health nurses in rural versus urban areas (n=56)

Table 2: Responses concerning resources (n=39) and competence (n=40) among rural public health nurses

Lack of interdisciplinary cooperation

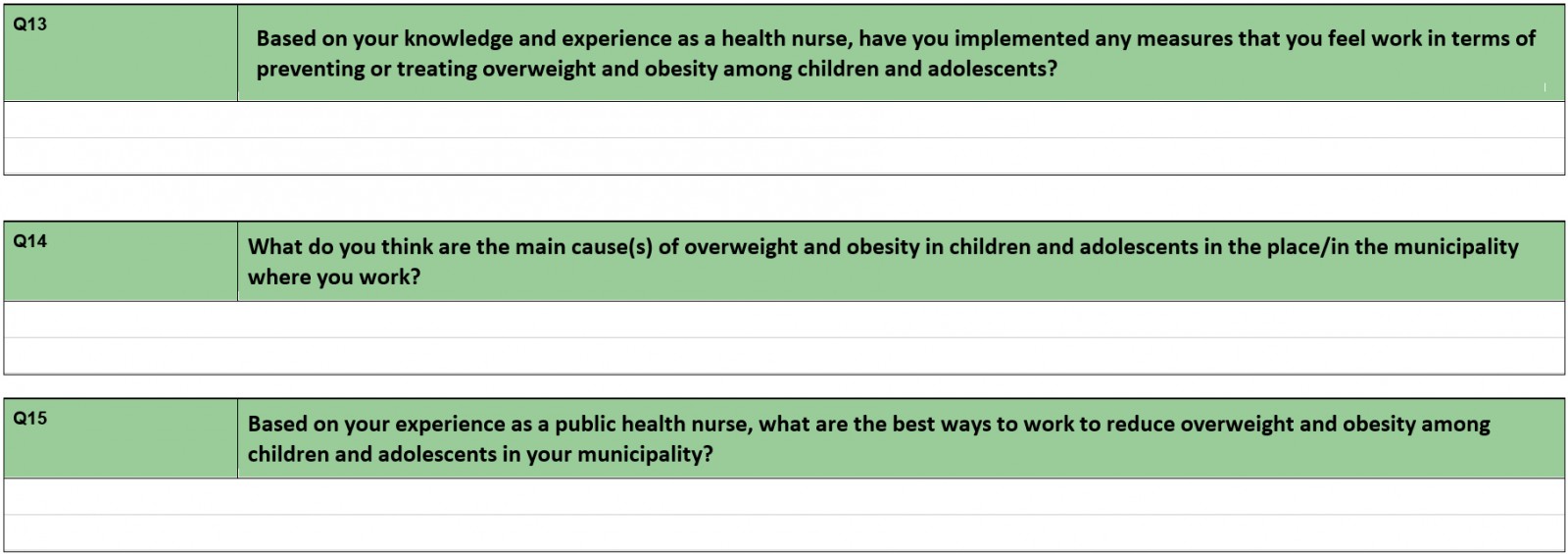

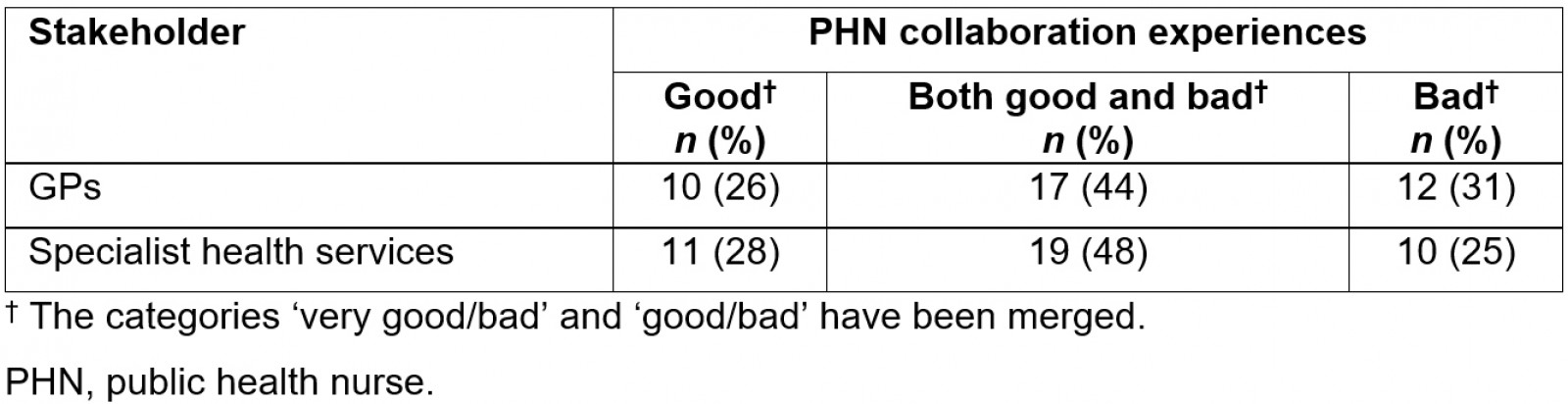

The rural public health nurses revealed ambivalence toward the quality of collaboration with different relevant stakeholders in their municipality. In the introduction we saw that the Office of the Auditor General argued that the lack of anchoring public health work across sectors in a municipality is the largest barrier to its success22. Our data confirm that the public health nurses were ambivalent about their collaboration with different stakeholders.

Only a quarter of the public health nurses considered their collaboration with general practitioners and specialist health service as ‘good’. At the same time, the interviews showed that several school nurses wanted more interdisciplinary cooperation. The main reason given for this was the complexity of the overweight problem:

Those who struggle with overweight often struggle with additional problems. Social issues, family issues, or economic. It is complex. I therefore miss a broader focus. [It would be good if] more stakeholders contribute. We as public health nurses might contribute with communication, guidance, support, motivation. But there might be other factors that also play a part. If it is economic, then other stakeholders need to be contacted. (Public health nurse, municipality 2)

The public health nurses suggested interdisciplinary cooperation to better grasp the complexity of being overweight or obese and saw improved cooperation as a solution for the lack of resources.

The questionnaire showed that a fairly large proportion of the public health nurses were ambivalent in their assessment of the cooperation with doctors and specialist health services. In the qualitative interviews, one of the explanations for this was the lack of a common understanding of the challenge they are facing:

We get the best results when we have a common understanding and work tightly with the target group, child welfare, educational psychology services, a common understanding of life mastery, mental health. There are different definitions and different ways of defining roles. We have a common responsibility. We have different competencies and background. (Public health nurse, municipality 2)

GPs were most often mentioned in relation to cooperation. The guidelines are that when the BMI level exceeds a given level, the public health nurses must refer the child to the GP. Several public health nurses experienced this cooperation as difficult, and the different understanding of overweight and the need for treatment was a recurring theme:

We talked a lot about the fact that the doctors don’t see the problem that the health nurse sees and that a disagreement occurred, and it gets unpleasant. Public health nurses received telephone calls from the doctors that wondered what they were up to. They don’t understand why the children are sent to them. In some cases, they react to the BMI cut off level for overweight. (Health coordinator, municipality 1)

The doctors don’t know what to do. They lack a code for diagnosis. They know that this is a group of patients that needs a time resource. It’s easiest for them to refer them to the specialists in the cities. (Public health nurse, municipality 1).

Interdisciplinary cooperation is considered a solution for handling a complex problem, and at the same time avoids leaving stakeholders alone in this situation. The main challenge is that public health nurses and doctors often interpret the concept of overweight differently. Since the overweight child or youth often has additional problems, doctors do not always see the weight problem as the most urgent. The health nurses even perceive the doctors not having a code for diagnosis when it comes to children’s overweight. The lack of a common understanding neither promotes constructive cooperation nor a holistic approach to treating children with overweight.

Table 3: Experiences of collaborating with different stakeholders among rural public health nurses (n=40)

Importance of seeing a child in context

One of the main purposes of implementing national guidelines was to secure a professional approach and equal access to public health services across the country14. This meant in praxis a strategy of ‘one size fits all’ of standardisation and quantifiable measures. The public health nurses in the present study expressed a sense that the lack of resources, ethical concerns around weighing, as well as dysfunctional cooperation, could be improved by considering a child’s wider context and by taking advantage of the experience and contextual knowledge of public health nurses. This includes knowing a child’s extended family, personal context, and her or his leisure activities:

In the countryside you often live in multi-generational housing, there are several houses on the farm. One boy that was overweight, he ate dinner at home before he ran on to the grandmother’s house, and the grandmother always said: ‘You have to eat something’. So, it is not only the nuclear family that has to be treated, it’s the whole extended family. (Public health nurse, municipality 1)

If one boy in 8th grade is in downhill skiing, which is a sport where you benefit from being heavy … then you need some weight, and you may be big with a lot of muscles, versus one that is doing gymnastics who is thin … so there will be huge differences, and we have to open for professional judgement, you cannot follow the guidelines strictly by the rules … (Health coordinator, municipality 1)

The familiarity with the children’s surroundings is thought of as of great importance when trying to uncover the reasons for their overweight. The public health nurses pointed out that you need this information to be able to do a good job:

I wouldn’t dare not to do the weighing and measurement myself. If I were sick that day, then I wouldn’t have sent out the letter without knowing who the kid was. I have to know who the letter goes to. (Health coordinator, municipal 1)

It was mentioned that the public health nurses had an understanding that this knowledge of the children was easier for rural public health nurses to achieve:

I remember discussing the importance of knowing the child with a colleague from Trondheim (a city in Norway), and she said there were too many children … they didn’t have a chance to get to know them all good enough … While here you have a better overview of who the children are. (Health coordinator, municipal 1)

The public health nurse feels that she must know the child before deciding how to proceed. This indicates that the BMI in isolation is not considered sufficient for the development of a treatment plan. Because of the various reasons for the overweight, some public health nurses also questioned whether the BMI cut-off values are too static. Another health nurse wondered if the cut-off is too low because what was perceived as overweight a few decades ago is considered normal these days. Making room for judgement about when a high BMI is a problem and adjusting the BMI cut-off level were brought up as respective solutions.

Discussion

The new standardised BMI screening-based guidelines were introduced in Norway with the aim to identify children who were at risk for overweight or obesity. In addition, it was aimed to secure professionalism and standardisation of healthcare services, no matter where in Norway people live14. The data revealed several challenges connected to the use of guidelines in rural areas. One big issue was the lack of resources and treatment options. This put the public health nurses in a situation that they felt was unethical. The mandatory phone calls to parents about their child’s overweight are difficult to carry out when it is perceived that there are no options for treating it. In some cases, this even led to an avoidance of carry out weighings.

To improve the work with overweight and obesity, and to compensate for the lack of resources, the public health nurses suggested a focus on improvement of interdisciplinary cooperation. Because most health-related institutions are in close proximity and the health stakeholders often meet informally outside of work, inter-agency cooperation may be easier in rural than in urban areas13,30. Lack of a common understanding and an ambivalent relationship between different stakeholders might risk a loss of opportunity of cooperation when following the national guidelines for prevention, identification and treatment of overweight and obesity. As it is now, cooperation is damaged according to the public health nurses, by different perspectives from doctors and public health nurses. The increased complexity of services in NPM-related coordination has led to a need for a management system that simplifies tasks and services in such a way that they can be measured and counted31. When stakeholders cannot see the complexity of the situation because they must focus on the narrow, measurable parts of their work, focusing on the codes for diagnosis, then this can lead to different perceptions on the obesity problem and complicate cooperation.

The school nurses viewed a holistic and contextual approach as essential for successful interventions with overweight and obese children and youth, in stark contrast to the NPM-inspired narrowing and standardising of the scope. The nurses underlined the importance of knowing the children’s surroundings, their family history, their leisure activities, and so on. Research suggests that the desire for a systematic evidence-based approach is reflected in a pressure to describe individuals in terms of pre-determined categories, which are then applied to ‘everyone’21. This makes it difficult to implement and take advantage of contextual and individual measures. The rural public health nurses perceive the rural context as a possibility to obtain more thorough knowledge about a child because of the transparent conditions rural areas often provide (where ‘everybody knows everybody’). The standardised and fragmented discourse in the context of NPM makes certain aspects of work invisible24. An example of such aspects is being able to have a dynamic adaptation to situational variability, which the nurses highlight as valuable, including a more pragmatic handling of BMI levels.

Although the public health nurses in this study largely demonstrated a common understanding of the topic, it cannot be claimed that this understanding is shared by all of Norway’s public health nurses. This might be considered as one of the limitations of this study. The geographical delimitation for the selection of informants (both for the qualitative interviews and the questionnaire) gave us the opportunity to explore the topic in depth, but at the same time losing the ability to generalise and thus the transfer value to other countries. However, the opportunity for in-depth exploration is one of the strengths of this study, considering that rural public health nurses’ thoughts and comments on this topic have received little focus in previous research.

Conclusion

Childhood obesity is one of the most serious public health challenges of the 21st century and is more prevalent in rural than in urban areas5-8. This article has explored the extent to which rural school nurses and other municipal stakeholders feel equipped to tackle the obesity epidemic by following national guidelines, and whether characteristics of rural areas can be used as an advantage in treating overweight and obesity among children.

The rural school nurses have thorough knowledge of the children and their surroundings, which provides them with experience-based knowledge that they can use in combination with professional judgement. They feel that they are well placed to determine an approach to an overweight or obese child. The use of sound judgement is, however, a break with NPM principles of a systematic, evidence-based and knowledge-based approach. Pre-determined categories and the logic of ‘one size fits all’ makes it difficult to explore local context and culture to better understand how individuals perceive, understand and act in the world they inhabit, obstructing customised solutions.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the members of the research team in project KOMPASS; Ellen Ersfjord (postdoctoral research fellow, University of Adger), Tanja Plasil (PhD) and Professor Line Oldervoll for comments and discussions during the project period. A thankyou also to the informants in this project, who spent time and resources to share their experiences with the project members. The authors also thank The Write Room and Gerda Wever for excellent work editing the article.

Statement of funding

This work was funded by the Regionalt forskningsfond Trøndelag (project number 285225), Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Institute for Social Research and Institute for Rural and Regional Research.