Introduction

Most countries are challenged with meeting the needs of rural and remote communities, particularly regarding the delivery of healthcare resources and services1, with significant urban–rural disparities in healthcare delivery in many countries2. This results in rural areas performing more poorly in comparison to urban areas on a range of health indicators3,4. Adults with multiple comorbidities in rural communities who require higher levels of care suffer the consequences of inaccessibility to healthcare services compared to their urban counterparts5. Access to health care in rural areas is frequently limited by transportation and availability of local healthcare workers6-8. While the state of rurality may vary across the world, challenges with water, sanitation, and electricity services often contribute to rural deprivation, further adding to the burden of ill health in rural areas9.

Little attention has been paid to the need for policy to address inequities in service delivery between urban and rural contexts. Policies are generally developed as ‘one size fits all’, unintentionally favouring the needs of urban healthcare systems10,11. There have been few coherent strategies that target rural communities and address their needs within the rural context. In other words, critical aspects of what makes rural different – geographically, economically, socially and politically – are often not fully considered when designing health programs and interventions. Furthermore, few countries have made progress in developing systematic methods that attempt to avoid unintended consequences for rural areas in the design of policy10.

The concept of rural proofing seeks to address this gap. ‘Rural proofing’ is a term used to describe the systematic application of a rural lens across policies, to ensure that those policies are adequately accounting for the needs, contexts, and opportunities of rural areas12. The fundamental objective of rural proofing is thus to ensure, from an early stage in the process, that there is rural sensitivity and understanding in ongoing conversations on policy development, initiatives, and any health strategies or guidelines.

There are currently no standards for accounting for ‘rural’ in the policymaking process in most countries13. Factors that need to be considered for rural proofing include geographic factors such as remoteness, topography, and infrastructure; population characteristics such as deprivation, demographic profiles, population numbers and density; the need for healthcare services demonstrated by utilisation patterns, clinical measures and epidemiological data; and other political, social, and historical factors that might impact on delivery and access13. The term ‘rural impact assessment’, akin to environmental impact assessment, as well as ‘territorial impact assessment’14, have also been used to describe the same process.

A term that is much more commonly used than rural proofing is future proofing, which refers to the process of designing or changing something so that it will continue to be useful or successful in the future if the situation changes15. Part of the process of future proofing rural health care is to ensure that young healthcare professionals (HCPs) are engaged with issues of rural health care, including rural proofing. In fact, an important element of rural proofing is to train young HCPs to play an active role in governing and creating policies to ensure not only the continuity of rural proofing, but also its success16-18.

To date, no study has attempted to understand the perceptions, ideas, and knowledge of young HCPs regarding rural proofing, yet they will be called upon to advocate for and lead the implementation of rural proofing efforts, to secure the future of rural health care. Building on that gap, we explored the knowledge and understanding of young rural HCPs in selected countries regarding rural proofing and the future of rural health care. This article focuses on the concept of rural proofing.

Methods

Study design

The study used a qualitative approach based on an interpretivist paradigm, in which the perceptions of young HCPs in relation to rural proofing and rural health care were explored, using interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) to collect data in two phases. The idea for the study emerged through conversations between WHO, Stellenbosch University’s Ukwanda Centre for Rural Health, and Rural WONCA, as part of WHO’s planning of work for a Special Edition of Rural and Remote Health dedicated to rural proofing of national health policies, strategies, plans and programs. The commitment to operationally include the viewpoints of young healthcare professionals in the Special Edition influenced WHO’s inclusion of the article.

Data collection

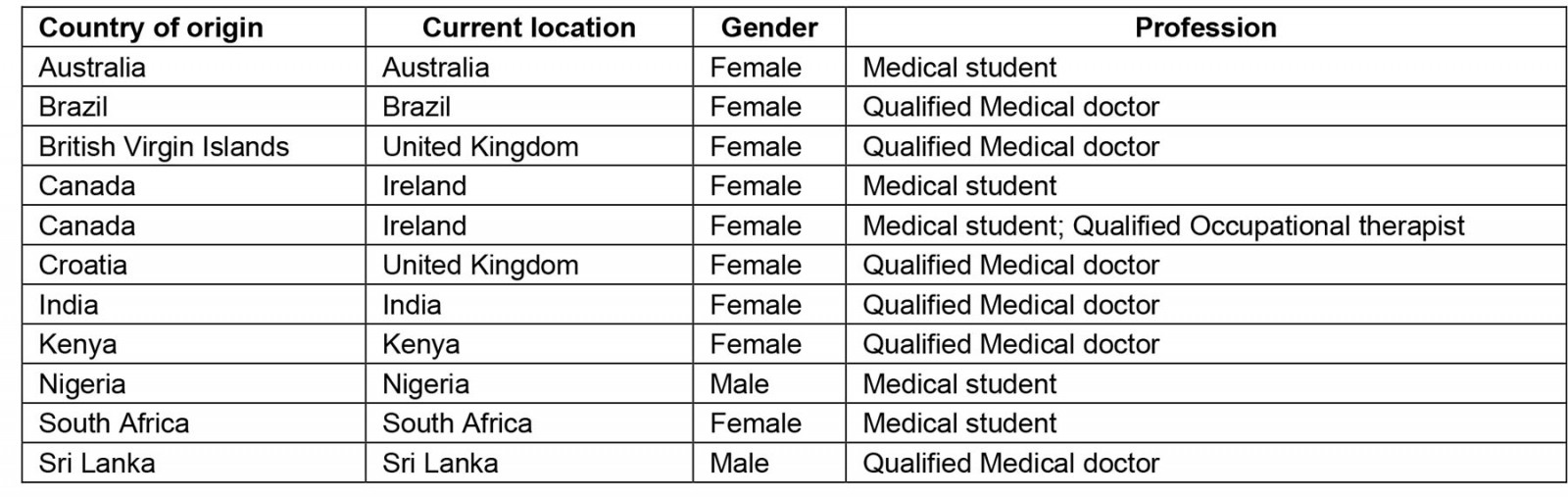

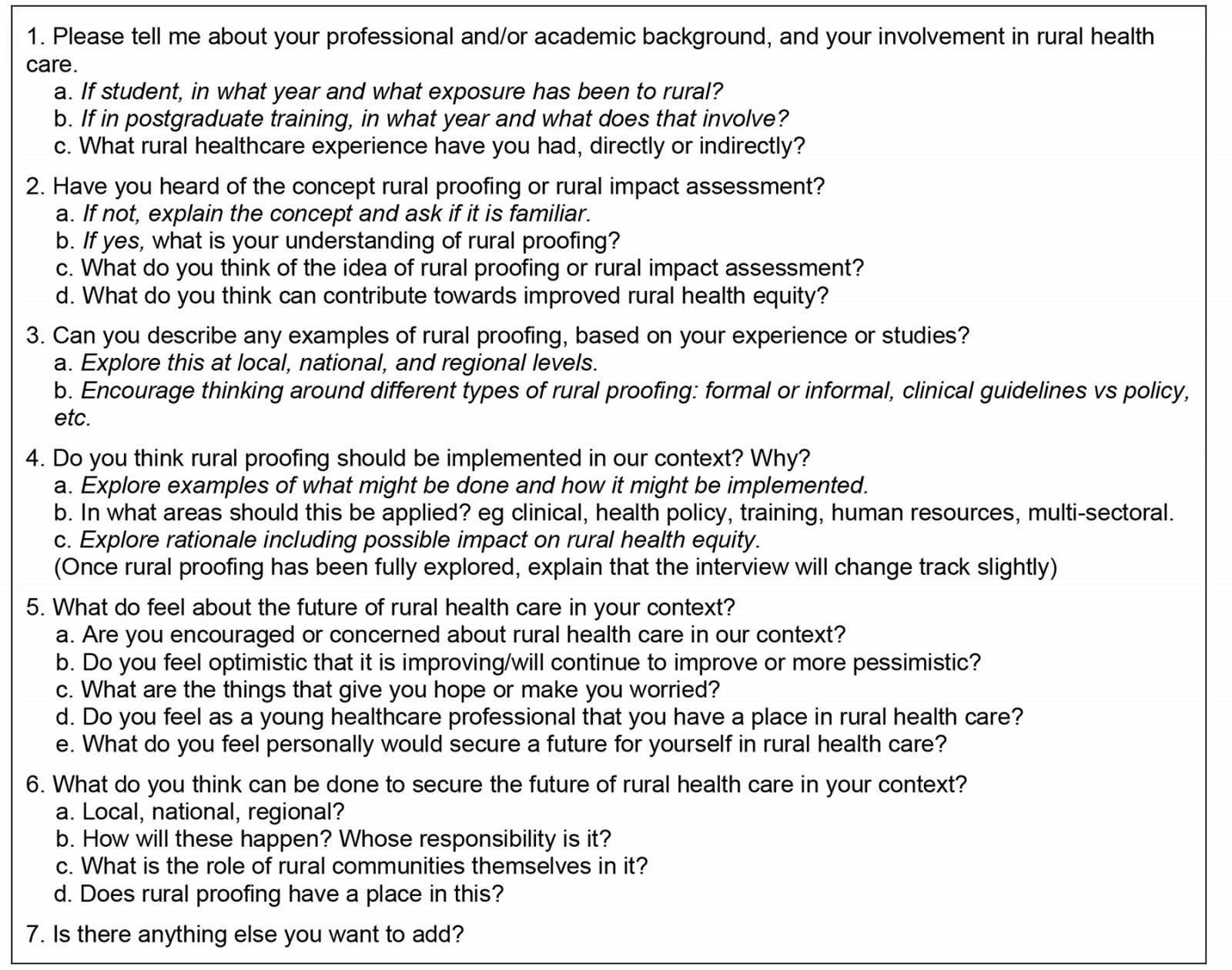

Phase 1: Phase 1 of the data collection involved semi-structured interviews. Data were collected from leaders of the group Rural Seeds, a movement for young rural HCPs, including students, with a rural health background or interest. Young HCPs were invited to participate in individual interviews via emails distributed to the Rural Seeds network. Young HCPs were defined as students, postgraduate trainees, or early career professionals (less than 5 years post final qualification). We deliberately targeted participants from different geographical regions. Eleven young HCPs agreed to participate, coming from Australia, Brazil, the British Virgin Islands, Canada, India, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Sri Lanka, and the UK. Interviews were conducted using Zoom videoconference by two members of the research team (Ian Couper and Ndivhuho Takalani) and recorded with the participants’ consent. The interview was semi-structured, using a standard set of questions to guide the process (Box 1), with exploration of issues raised by participants and conversation being facilitated to obtain rich data. The interviews were conducted from December 2021 to March 2022, each with a duration of 30 to 60 minutes. Recordings were fully transcribed, cross-checked by the investigators (IC and NT), returned to participants for member checking, and imported into ATLAS.ti 22 (https://www.atlasti.com) for analysis.

Box 1: Interview questions

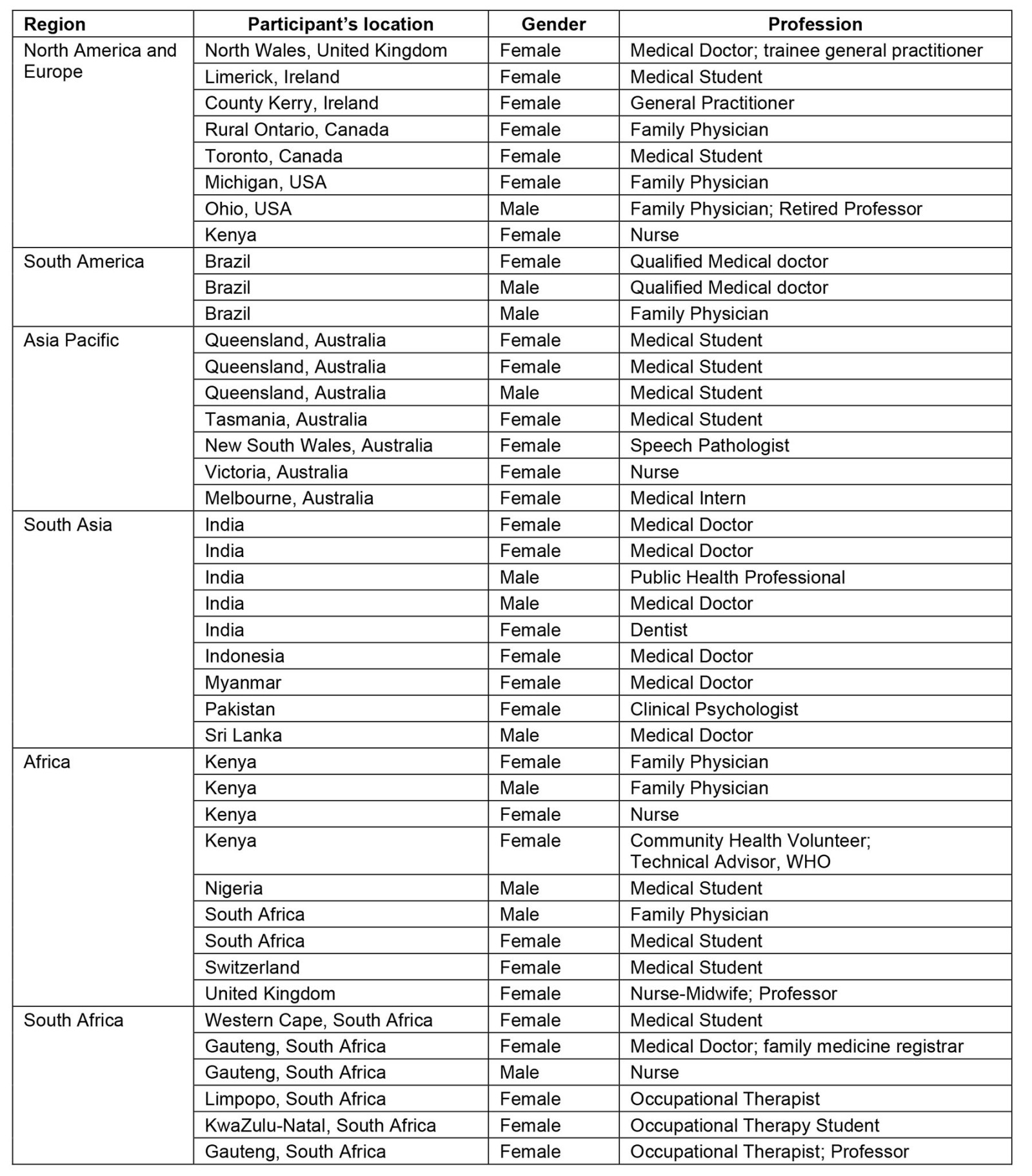

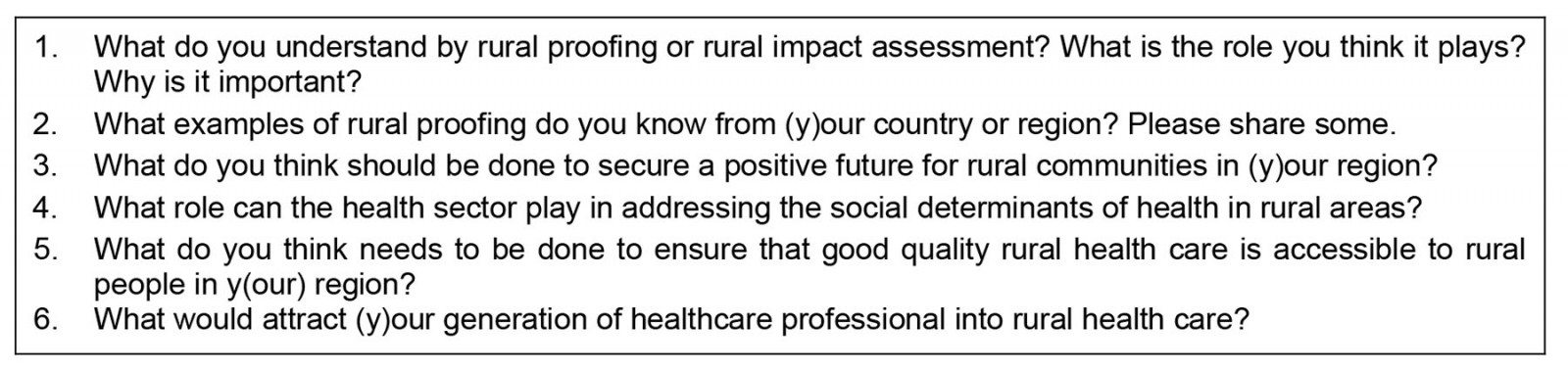

Phase 2: Selected interviewees who showed interest and who were distributed across the regions of the world were invited to take the lead in organising Rural Café discussions. Rural Cafés are engagements where a diverse group of health professionals discuss rural health-related topics; they are a project that has been commonly used by Rural Seeds to interact with members and explore such issues19. These interviewees became part of the research team and arranged the Rural Café events regionally, with the support of the two lead researchers (IC and NT). They invited other, mostly young, HCPs from their region, whom they thought would make a good contribution to the discussion, to join the panel; in a few instances, senior professionals identified by Rural Seeds members as mentors were also included in the panels. The panels, which served as focus groups, were asked to respond to and discuss a series of questions like those posed to the interviewees (Box 2). The following regional online FGDs took place, with the number of participants in each FGD shown in brackets: Africa (9), Asia-Pacific (7), North America and Europe (8), South Africa (6), South America (3) and South Asia (9). All participants joined a Zoom meeting using a shared link. The Rural Cafés were broadcast live on the Rural Seeds YouTube channel. Comments from the audience were shared via the Zoom chat function. Once again, recordings were transcribed and cross-checked by two investigators (IC and IL).

Box 2: Focus group questions

Analysis

Thematic analysis was used to identify common ideas and perceptions. The interviews and FGD transcripts were initially examined separately by three members of the team (IC, IL, and NT) to identify initial codes and categories, and develop a coding index. These researchers then reviewed each transcript to assign the data to codes and categories, and key themes were identified by continuously cross-reading transcripts, evaluating patterns and their relationship. The themes fully overlapped between the individual interviews and FGDs, so these were merged into a single analysis. Data were exported from Atlas ATLAS.ti22 into Microsoft Excel. The themes were then organised in an Excel spreadsheet, with data linked to the theme and categories and shared with the full research team, which reflected on the original data. Participants’ views were checked to be accurately represented in the final themes, and they provided input to the final analysis. The role of the participant researchers in the team was particularly important in ensuring trustworthiness of findings.

Ethics approval

All respondents participated voluntarily. Anonymity and confidentiality were assured in the interviews; the potential risk of being identified related to publication of results was included as part of the informed consent process. In the FGDs, participants were made aware of the difficulty in ensuring anonymity and confidentiality given the open nature of the Rural Cafés but were assured that these would be applied in the transcriptions and reporting. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Ethics approval was granted by the Stellenbosch University Health Research Ethics Committee (Project number N21/10/106).

Results

The 11 interviewees consisted of medical doctors and medical students from 10 countries classified at different levels of development. The six FGDs ranged from three to nine participants. Most were medical doctors and medical students, though there were other healthcare workers in a number of the groups, mostly nurses or rehabilitation therapists. Participants mostly came from the country of the organiser of the Rural Café. (See Supplementary tables 1 and 2 for demographic details of participants.)

The common themes that emerged were the value of rural proofing, implementation of rural proofing, and actors in rural proofing. These themes were found across both the interviews and the FGDs and are thus combined in the presentation of the findings that follow.

Overall, the state of rural health care globally was seen to be problematic, with a lack of equity, difficulties in access to health care, and multiple socioeconomic challenges, particularly in relation to living conditions, human resources, and infrastructure. Despite variable and sometimes limited prior understanding of the concept of rural proofing, it was seen to be of great value in making a difference in rural health care, with examples from several contexts being shared.

The value of rural proofing

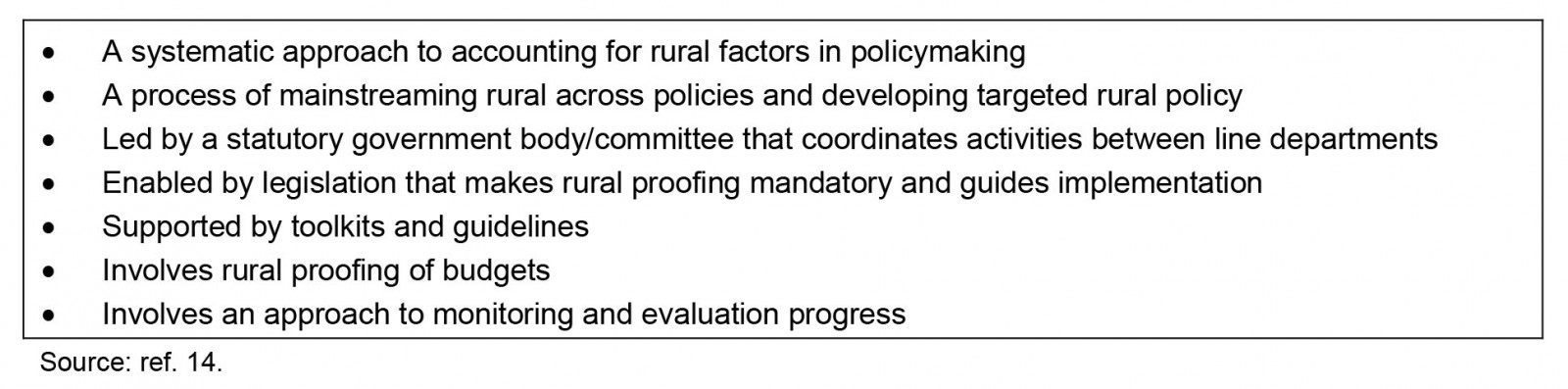

There was significant discussion in both the interviews and FGDs on the concept of rural proofing – its meaning, value, and potential impact. Initially, very little information was given about the concept, and respondents were encouraged to give their impressions based solely on the information that they had. This was done to gauge their current understanding. Then, as the discussion progressed, additional aspects of rural proofing principles were shared, where appropriate, which often led to recognition of these in the contexts of the participants, and/or the sharing of examples. While these conversations were very much part of the explorative interview process, they covered many aspects of rural proofing. This mapped well against the key principles for rural proofing listed in the South African Rural Health Advocacy Project’s Rural Proofing for Health Guidelines14 (Box 3), and often led to a deeper exploration of the role of the health workforce in rural proofing.

When participants were first asked what they thought about rural proofing, their level of knowledge of the term ‘rural proofing’ was quite low.

To be fair, I am not so familiar with this concept. (INT11, Brazil)

I have heard of it, but I haven't heard of it for years. (INT8, United Kingdom)

The content was, however, well described in one FGD.

Rural proofing is… a kind of commitment by the government to review and examine the various public policies that it applies to ensure that the rural areas are not disadvantaged … many times wherever public policies are applied … urban areas invariably get the advantage of those policies… (FG, South Asia)

Participants mostly saw rural proofing as being the idea that one is seeking to make a difference to rural health care.

By rural proofing, you are talking about actions and things that we can do to improve the healthcare system in rural areas. (FG, Brazil)

What I understand is it’s … a sort of commitment by the authorities to … [ensure] the public policies and the … rules and regulations are not disadvantageous for rural people, or … comply even with the rural communities. Or the rural communities are not … ill-treated due to the public policies and the regulations that are in place. (INT9, Sri Lanka)

One participant described rural proofing in terms of the deficit in preparation and/or training of health professionals that needs to be addressed.

From my understanding of it, it’s … a recognition that … the people who often end up in rural environments aren’t necessarily equipped to be able to function in those environments … you apply your cookie cutter medical school curriculum to an environment that does not necessarily fit that description. (INT8, UK)

When the term was defined, or explained differently, it was immediately understood by participants, who then argued strongly for its value, regarding health care and action on the determinants of health.

I think that the idea of rural proofing is a good one … it’s an advocacy tool, and I think that it can work very well. (FG, South Africa)

Rural proofing would definitely benefit both the rural communities … and even the entire health workforce, because when you talk of rural proofing, it’s including health, or like the policies involving your basic sanitation ... Those need to be strengthened, because I see that as a starting point, like basic sanitation, water, electricity and even transport, and even the land. (INT10, India)

Despite their varied understandings, most participants shared several examples of what they considered to be rural proofing (or the result of rural proofing) in their contexts.

Clinics being built in rural communities … it is important to make sure that even clinics that don’t ... have the knowledge about certain conditions or the special care that rural communities should be receiving, should be backed up by specialized outreach services. (FG, South Africa)

One example was shared with doubt that it was an illustration of rural proofing, but provided an example of the patient-centred focus that should ideally emerge because of rural proofing health policies and programs.

One thing that could possibly fall under rural proofing is the district nurses that we have in Wales. [These] are nurses in the community that see the patients in their homes, and sometimes what they will do is they will see a patient, and they’d think … I’m a bit concerned about this patient; would you mind also doing a visit … it’s just useful in a rural community to have that feedback from another healthcare professional … especially for patients who are housebound. (INT8, UK)

There were some participants who felt that rural proofing was palpably lacking in their contexts.

I have to be honest, I have noticed more of a lack of rural proofing, than actual rural proofing. (INT8, UK)

I don’t remember anything right now. Maybe especially because in Brazil, we don’t have guidelines, or anything related to that. (INT11, Brazil)

Questions were raised about the kind of response there might be to the term’ rural proofing’, and whether it is a helpful one.

I do find that the term ‘rural proofing’ is a little bit provocative. It’s more of a defensive thing … although I think it’s a helpful term in legislation and accreditation, it’s probably less helpful in talking about disparities, inequities, those sorts of things, because it does come across as rural trying to … ‘get their share’ … That means we treat everybody the same. But as we all know, equity is not about treating everybody the same … our culture is one that argues against splitting out rural from urban or any minority group from … the rest, and just saying everyone matters and we are going to do the same for everybody. (FG, South Africa)

One participant explained how rural proofing should also benefit marginalised groups within rural communities.

Rural proofing … would come in handy by making sure that not only is health care provided to … the general rural community, but also Indigenous members of the community ... Rural proofing can not only ensure accessibility but protect against discrimination of Indigenous community members. (INT7, Australia)

Related to this, it was noted that local application is critical, and this becomes challenging in a context of great diversity.

I do think it’s important to have rural proofing health policies but then again it really needs to be tailored to the needs of the local population and I don’t think it will work in the [countries] that are heterogenous and high in diversity. (FG, South Asia)

Rural proofing was seen by many as a key to achieving equity in health care.

I’m thinking rural proofing will be one of the best ways in which we can ensure there is rural health equity … because whenever we demand that, whether it is in education, in agriculture, in health care especially, that you tell us how this will impact. For example, human resources, how will this impact? Will it pull human resources to rural areas, or away from? … that will be an important component to start at least bridging that gap [in rural health care]. (INT2, Kenya)

Box 3: Principles of rural proofing for health

Strategies for rural proofing

Participants discussed a range of rural proofing ideas and strategies that they thought needed to be put in place, as well as the enabling framework that is needed and the challenges to rural proofing. Strategies related to education, health professional curricula, infrastructure, and intersectoral action.

Strategies for rural proofing are seen to require focused attention, to change the culture of the healthcare system.

I believe one of the most important things … that I can see in Brazil is to pay more attention in such areas … I mean policies, well-written, debated, that people really care about it. So, change some cultural aspects of the rural healthcare system, decentralise it. (FG, Brazil)

The starting point for all strategies was seen to be driven by the local context. This involves engaging with communities as described in relation to improving rural health care.

You need to have that knowledge about what’s happening in the community, not just in the healthcare setting ... You need to know the pharmacy, you need to know the food delivery people, the social services people as well, all the carers that are available in the area, the district nurses. (INT6, UK)

It starts with opening up these platforms to the communities themselves to find out what do you think needs to be changed at this scale, and what can we do to make your life better, or to make health more accessible to you, or to make you more aware of what it is you need to do to take responsibility for your own health … (FG, South Africa)

This means there needs to be consultation with frontline workers and patients.

Someone who has the capability to change the policy that’s in place, should be also running the assessment [of the policy] ... But they should be considering the feedback that they are getting from frontline staff and patients … (INT6, UK)

Linked to this was the expressed need for ongoing evaluation of interventions in rural communities to ensure solutions are relevant and sustainable.

In terms of securing … a positive future for the rural communities in my country, … doing a continuous assessment of the local population needs and challenges … and its assessment tools can be very essential. (FG, South Asia)

The greatest challenge in rural proofing policy is implementation of the rural-responsive measures that it may produce, which seem to be related to human resources and ultimately to funding.

As far as rural proofing goes, I don’t know whether that will make a difference if we can’t provide the things that are set in policy … (INT6, UK)

There needs to be an argument made for the way funds are allocated as a basis for rural proofing.

Health care is probably the black hole of the government’s money, and they don’t really like spending into our future … we really need to validate what we’re saying when we lobby them for change or for … rural proofing and future investment with statistics … and … I think that the way that we allocate resources in rural areas needs to be … very individualised to local community, and the consultation needs to come at a level of local community. (FG, Asia-Pacific)

Improving education as a route to improving rural health was seen to be a major focus in rural proofing.

Health literacy is quite poor in rural areas … there aren’t even enough teachers to work there… Because of a lack of education, that leaves an abundance of issues, like not being able to understand why smoking is bad, and therefore, smoking a lot, and therefore developing comorbidities. (INT7, Australia)

In terms of attracting doctors and other healthcare workers, exposing students to rural medicine as early as possible was advocated as an important strategy.

I noticed something that exposure to rural medicine should be started very early, at school or internship. In my perspective, I wasn’t personally introduced to rural medicine during my internship. (FG, Africa)

One of our activities at Rural Seeds is conducting … workshops in medical schools to talk to medical students about rural health. We discover that most of the time, the students, they get flash ideas of working in urban centres, and negative talks of working in rural areas. So, we are trying to realign, or to attract them to the rural health. (FG, North America)

This requires a change in healthcare professional curricula.

I feel rural health is not really spoken about enough in medical circles … I really feel like as students, we should learn more about rural health when in school, and that way, we are more conscious of it, and the need for us to advocate for those in rural communities. I feel if people understand rural health from medical school and the problems that they face, then they are more willing to go into these communities, even if it is for a short term. (INT4, Nigeria)

This should be continued in postgraduate training.

Right now, in family medicine, residents, we are talking more about that, because we are in different places … we are always exchanging experiences and trying to think of little things that we can do so that we can ensure better outcomes in the rural areas. (FG, Brazil)

Infrastructure is another area that was singled out as requiring rural proofing, although from the perspective particularly of retaining health professionals.

They do not give enough infrastructure to the rural areas. So, there must be a policy that states for instance the issue of the road network. There must be a policy that actually obligates people to develop that, to develop housing in rural areas, to develop water and sanitation in rural areas … one of the major reasons why … most doctors and healthcare professionals I have met don’t work in rural areas, is poor infrastructure ... (INT2, Kenya)

Actors in rural proofing

Developing and implementing rural proofing strategies requires a range of people at different levels to be involved. Everyone has a role to play: organisations, individuals, government at different levels, professionals, and communities.

I’d say it’s everybody’s responsibility. For example, there are so many different organisations, civil society organisations, medical, nursing associations, that influence policy in Kenya. It’s the responsibility of anyone who is working, especially in the rural area … because state [actors] or state [agencies], are made up of people. (INT2, Kenya)

All sectors of the community must be involved, and due attention must be given to linking health and social services based on an understanding of community needs.

It’s also very important for us healthcare professionals to be part of that, and then also to include religious leaders and cultural leaders … if there are people who are experiencing abuse at home, who are experiencing all sorts of problems, the community leaders and the religious leaders, they must be part of the stakeholders because they are the ones who have the proper insight into how they approach those specific problems at that given time. (FG, South Africa)

How do you get governments to listen, and to make a decision on rural health and social care The most important thing is thinking how we can actually link health and social care together for the benefit of communities. (FG, Africa)

Health professionals can assist in empowering rural communities to advocate for their own needs.

I think a big role we have to play is community empowerment, empowering them to know what they are entitled to. Empowering them to know what it means to get health, to know what it means to get access … if they don’t know, they won't be able to ask for it. When they are empowered and educated to know what it is that they need … then I think they can play a bigger role, because right now, they are still at the background. (INT2, Kenya)

At the same time, there must be work done at a national level to have impact.

… what I have seen work, cascading down, is once we get the concept of rural and rural proofing into policy at national level, that will be a great win, because counties and every other person in schooling in rural areas, look to national policy. Once something is made policy, then you have the authority so that it can be implemented. If it’s not policy, we are not doing it. But if it is policy, yes, we have a right to ask … to allocate resources. (INT2, Kenya)

There needs to be a whole-of-government approach to addressing recruitment and retention of healthcare workers in rural and remote areas.

Looking at infrastructure, education, accommodation, and all of that … how do we get the government, or whoever is responsible for doing that, to make it so that they do look at it holistically? (FG, Asia-Pacific)

HCPs, and their organisations, are seen to have a vital role to play in bringing about change.

It’s up to us all to pressurise our own people to focus more on the primary health care, that is rural health care, and through them, to pressurise the policymakers, the Parliament … the most important thing is to make them realise, make them insightful, that rural health care is very important in different ways … because it’s primary health care or rural health care, it’s the majority’s health care. Majority health care is important in getting votes as well. (INT9, Sri Lanka)

This means health professionals becoming involved in advocacy; in other words, it means people like me working for rural health and advocating for rural health, and making sure we get it on the agenda. So, advocacy is going to really play a big role. (INT2, Kenya)

If this advocacy can be done as a multidisciplinary team, it will be so much stronger.

I think if we could … not have only one association that is busy equipping HCPs but also occupational therapists, pharmacists, community health workers, health promoters, if you have policy developers, politicians, all of these people collaborate together, I think a beautiful outcome would come from that. (FG, South Africa)

Discussion

This article explores the ideas of young HCPs from selected countries across six continents regarding rural proofing. It was evident across the series of interviews and FGDs that the concept of rural proofing is understood, even while the term ‘rural proofing’ may not be well known. This raises questions about the usefulness of the term. Participants agreed that the state of rural health care could be addressed through implementation of a comprehensive approach to rural proofing, with the involvement of a range of actors in addition to HCPs themselves and the communities in which they work. The findings suggest that rural proofing is essential to the future of rural health care.

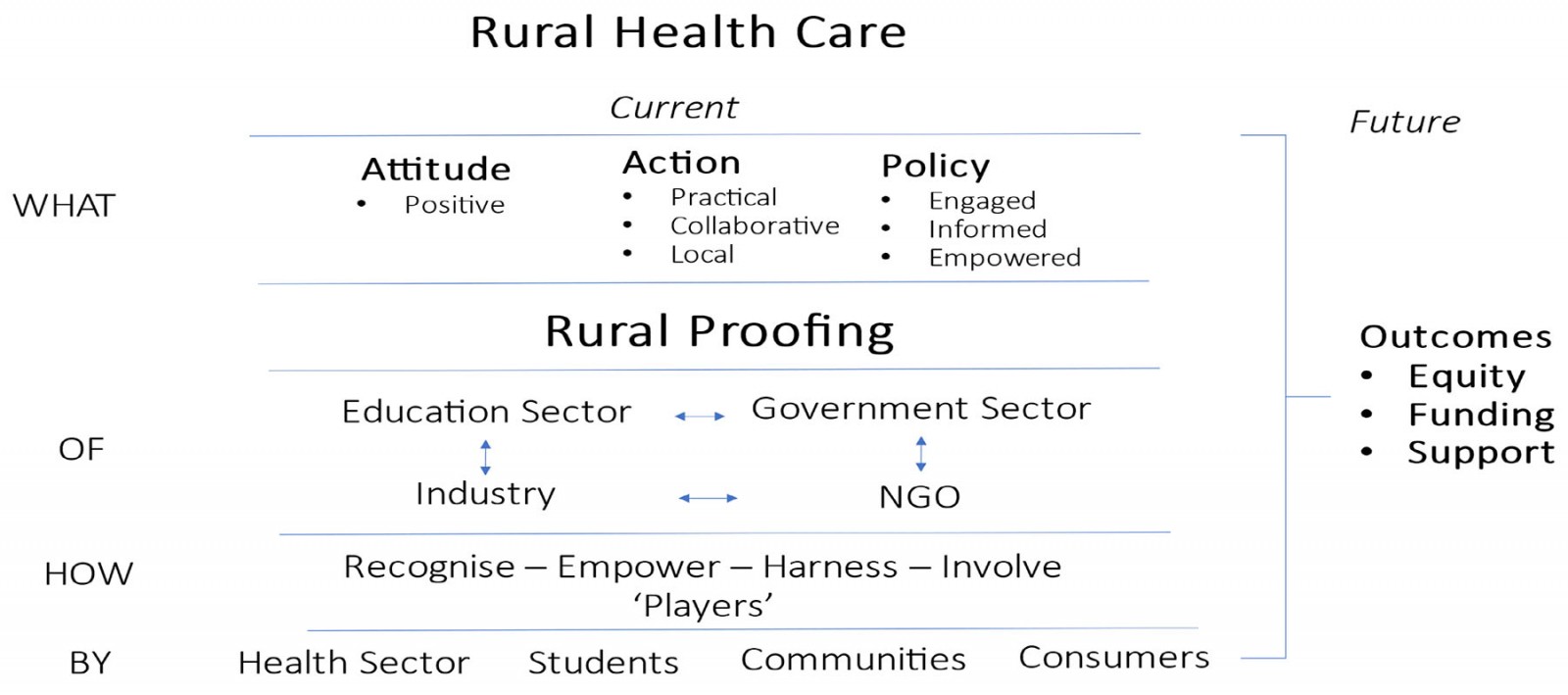

Figure 1 summarises the findings, highlighting the focus of the participants on making a difference to the current state of rural health care. This is based on positive attitudes, collaborative action and engaged policy development. Rural proofing can be achieved across multiple sectors that impact health, if there is recognition of the range of actors. This allows each actor’s strength to be utilised effectively, so they are empowered to be involved. These actors include young HCPs and students, communities, and consumers (patients). The expected outcomes of this for the future are greater equity, improved funding, and enhanced support for rural health care. This conceptualisation adds to the understanding of rural proofing in the literature. Its significance lies particularly in its action-orientated, inclusive, and empowering approach to this concept. It builds well on the guidelines for rural proofing referred to previously14.

It is clear from this that young HCPs want to see practical implementation of meaningful solutions to the difficulties they have seen and experienced in rural health care; it is not simply about developing high-level policies without positive impact on local communities. Participants described a need for practical solutions that are appropriate to rural communities, countering geographic narcissism20 and structural urbanism proactively21. They also described a need for working horizontally across sectors, from local to national policymakers and planners.

The young HCPs interviewed in this study argued that the ‘one size fits all’ approaches have no place in current healthcare planning. Policies need to account for the heterogeneity of contexts and diversity of populations within rural and remote areas, and implementation of responsive measures. The young HCPs further agreed that governments and relevant policymaking bodies do not invest sufficient time and effort to address the issues that underlie the inaccessibility of health care in rural and remote areas, as highlighted by Swindlehurst et al10. This was seen to be one of the major contributors to the continued neglect of rural and remote communities in general. The HCPs agreed that one of the difficulties in accounting for the rural context in policy development and strategic planning is that there is little guidance on how this could be done. This is the critical role that rural proofing can play if this becomes entrenched in policy and strategy processes13.

Throughout the interviews and FGDs, a common theme related to rural proofing involved the education and exposure of medical students and young HCPs to rural health care. Many participants discussed how their training related specifically to urban areas; as a result, they were unsure that they had the tools necessary to meet the needs of rural populations. They also spoke of a lack of enthusiasm towards rural health care in universities and limited opportunities for on-the-ground rural health training. The need to address these issues, and strategies for doing so, have been widely discussed in the scientific literature. This has been demonstrated in multiple literature reviews16,22-26, including in this journal27-29. Evidence-based educational strategies that impact on rural health care form a significant part of the WHO guidelines on improving rural health workforce30. For this reason, in any policy discussion related to rural proofing, the appropriate education of health professionals for rural health care needs to be included.

The findings suggest a wealth of wisdom and understanding among young HCPs that needs to be harnessed. Further research that captures the perceptions of a wider group of young HCPs should be considered. This includes obtaining feedback on a series of possible interventions that may be included as part of rural proofing.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the place of rural proofing in addressing the state of rural health care.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the place of rural proofing in addressing the state of rural health care.

Recommendations

The following recommendations emerged regarding to rural proofing:

- Increase familiarity with the concept of rural proofing and how it can be actioned across the health policymaking and planning cycle, through advocacy and publications such as this.

- Adapt rural proofing processes for local contexts addressing the heterogeneity of populations inequities across rural contexts and vulnerable populations.

- Rural proof the ways in which health workers are recruited, trained, and retained in rural health care.

- Ensure that rural proofing policy commitments are properly instigated (eg through legislation), governed (eg through policy coherence across sectors and levels), guided (eg through handbooks and toolkits), resourced (through budgeting and human resource allocation), and measured (through equity-oriented monitoring and evaluation) to result in implementation

- Adopt a whole-of-society approach to rural proofing to address social and environmental determinants of health.

Strengths and limitations

The perceptions of this group of young HCPs are not necessarily representative and thus cannot be generalised. However, the study targeted a group of people across the world who are playing a role as leaders among young healthcare professionals and have a particular interest in this area. They were an appropriately informed sample who provided rich information.

We acknowledge that, given the nature of Rural Seeds, the participants were almost all medical professionals, and thus the inclusion of other health professionals, such as nurses, pharmacists, and rehabilitation therapists, was very limited.

Involvement in the research team as participants enabled the voices of young HCPs to be authentically expressed in the process, ensuring that the research was truly participant led31.

It was originally intended that the two phases would speak to each other and provide different information but in fact the degree of overlap was such that they were merged. Thus, the developmental understanding that was expected did not occur. Also, the ability to test out ideas raised in the first phase was not able to be done. However, the data collected were substantially reinforced by the process.

Conclusion

Our study reinforces the need to engage the wisdom of those who have a deeper understanding of rurality by recognising, empowering, harnessing and involving current and future health workers, communities, and patients at the earliest stages of policy development and in the implementation and ongoing monitoring and evaluation of policy that influences healthcare services in rural areas.

This should be supported by rural proofing at all levels, underpinned by an approach that values local communities who are engaged, informed, and empowered through the process. At the same time, it is clear in the minds of young HCP leaders that, without a strong rural health workforce, rural proofing will not be possible.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the tragic death on 24 June 2023 of Mustapha Tukur, a medical student leader from Nigeria, who was a Rural Seeds ambassador and part of the team of authors on this paper. We dedicate this article to his memory.

We thank all participants for their time and willing contributions.

Ukwanda Centre for Rural Health, Stellenbosch University, gratefully acknowledges its partnership with the WONCA Working Party on Rural Practice and Rural Seeds in carrying out this research.

Funding

This research and the resulting article were commissioned to Stellenbosch University by WHO, through WHO Agreement for Performance of Work with Stellenbosch University, registration number 2021/1166157-0. This is linked to the WHO and Government of Canada project entitled ‘Strengthening local and national primary health care and health systems for the recovery and resilience of countries in the context of COVID-19’.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

This article represents solely the views of the authors and in no way should be interpreted to represent the views of, or endorsement by, WHO. WHO shall in no way be responsible for the accuracy, veracity and completeness of the information provided through this article.

References

Supplementary material is available on the live site https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/8294/#supplementary

You might also be interested in:

2019 - Teleneurology service provided via tablet technology: 3-year outcomes and physician satisfaction

2007 - Is walking barefoot a risk factor for diabetic foot disease in developing countries?