Introduction

According to the 2023 universal health coverage monitoring report, people living in rural settings and the poorest households experience less coverage of essential health services than national averages1. Estimates by WHO suggest that 51–67% of rural populations lack adequate access to essential health services in their communities, leaving behind about two billion people, a quarter of the current global population2.

UN and WHO member states governments have recognized that the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development depends crucially on the transformation of rural areas3. The importance of tackling health inequities and their socio-spatial determinants has been highlighted in World Health Assembly resolution WHA 74.164, the 2023 UN General Assembly-endorsed Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage5, and work by WHO and partners on primary health care (PHC)-oriented health systems strengthening6. The Limerick Declaration on Rural Health Care in 20227 specifically addressed the importance of tackling rural health inequities.

Between July 2021 and March 2022, 51 experts from around the world contributed (as speakers, co-chairs and discussants) to an eight-part webinar series on rural health equity8, the content of which is overviewed in Table 1. The series was convened by WHO and the World Organization of Family Doctors Working Party for Rural Practice (Rural WONCA), with inputs from partners including the OECD and agencies in the UN Inequalities Task Team subgroup on rural inequalities (which, during 2021–22, included a focus on reducing inequalities in public service provision in rural areas in its workplan9).

The aim of the webinar series was to share technical/operational know-how, insights and lessons learnt for both health systems strengthening and action on social and environmental determinants of rural health inequities. The target audience included staff in advisory, programming and technical levels in health authorities, the health workforce represented in WONCA and other global associations, researchers in academia and members of non-governmental organizations, civil society and multilateral system partners.

The authors collaborated for a thematic analysis of all webinar transcripts during 2022–23. The research aimed to inform future normative and capacity-building work, including a forthcoming WHO course on health equity in the context of integrated rural development planning and WHO work on rural proofing for health equity. The objective of the research was to test the framing of rural health equity that underpinned the design of the series and explore the implications for governance approaches. The research drew from current (eg pandemic-informed), cross-regional/global and interdisciplinary narratives to consider drivers of rural health inequities within and beyond the health system. In this way, it contributed to taking stock of current problem conceptualization and identifying emerging prioritization by experts of ways forward. Initial and partial emerging findings were presented at the Limerick Rural Health Conference in 2022 and published as an abstract in the conference collection in Rural and Remote Health10.

The research question addressed by this study is ‘What do the 51 expert narratives from the WHO Rural Health Equity eight-part webinar series convey about the framing of rural health equity and related governance approaches?’ In this research, health governance can be understood as ‘a wide range of steering and rule-making related functions carried out by governments and decision-makers as they seek to achieve national health policy objectives6. Lehmann and Gilson describe these functions as including ‘strategic policy frameworks, effective oversight, coalition building, regulation, attention to system-design and accountability’11.

Table 1: Overview of the eight-part Rural Health Equity webinar series8

| Webinar/presenter names | Title of presentation |

|---|---|

|

Webinar 1: ‘Lessons in rural proofing of health policies, strategies, plans and programmes’, 15 July 2021 Chairs and rapporteurs: Theadora Swift Koller (WHO/HQ), Bruce Chater (Rural WONCA) |

|

| Koller TS, Beltchika N, Mane E | The rural of rural proofing in building forward better for the rural poor |

| Rensburg R | Rural proofing: lessons learnt – South Africa |

| Wilson B | Rural Proofing for Health Toolkit: Country experience – England |

| Montero J | Rural Development National Policy – Chile |

| Moreno Monroy A | OECD principles on rural policy and rural proofing of sectoral policies |

| Koch K | The WHO Handbook on Social Participation for UHC – reflection on how it can be used to support community engagement in rural proofing |

|

Webinar 2: ‘Social participation, inclusion and community engagement approaches for the health of indigenous peoples in rural and remote areas’, 9 August 2021 Chairs and rapporteurs: Theadora Swift Koller (WHO/HQ); Geoffrey Roth (member of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues); Bruce Chater (Rural WONCA) |

|

| Mohan P | Community engagement for health and well-being of indigenous populations: Experiences from South Rajasthan, India |

| de Moura Neto FJ | Intervention as the President of CONDISI of Ceara (Northeast) and Vice-coordinator of the National CONDISI Presidential Forum, Brazil |

| Goklish, NA, Sinquah FL | COVID-19 response from the White Mountain Apache Tribe |

| Le Blanc J | Social accountability with indigenous communities for training of health professionals: Experiences of the Northern Ontario School of Medicine, Canada |

| Aboubakrine MWM | Participation of Indigenous women in the COVID-19 response in Mali |

| Quipallan AV | Statement as representative of the Mapuche People |

| Peachey L | Statement as rural GP and founder of the Australian Indigenous Doctors Association |

|

Webinar 3: ‘Policies to develop, attract, recruit and retain health workers in rural and remote areas and promote gender equality for rural women through health workforce policies’, 15 October 2021 |

|

| McIsaac M | Promoting gender equality for rural women |

| Acluba E | Working in geographically isolated and disadvantaged areas and with children with disabilities in Cagayan Valley in Luzon |

| Ballard M | Community health workers in rural areas: opportunities for gender equality |

| Nashat Hegazy N | Why it's important to establish training for the health workforce in rural areas, and how to do it? |

| Doumbia I, Maiga H | Experience of Gao region in the training, recruitment and retention of health workers in rural and remote areas of Mali |

|

Webinar 4: ‘Intersectoral action with the agricultural sector for strengthening primary health care’, 29 November 2021 Chairs and rapporteurs: Theadora Swift Koller (WHO/HQ); Bruce Chater (Rural WONCA) |

|

| Mugambi J | Bringing the rural health physician perspectives into cooperation between agriculture and health sectors |

| Ivanov I | Cooperation between the health and agricultural sector for occupational health safety and services |

| Pica Ciamarra U | One Health and poverty reduction: a livestock perspective |

| Buzeti T | Programme Mura: The experience of linking health, agriculture and rural development for health equity in Slovenia |

| Valentine N | Discussant in her role as lead for the Multi-country Special Initiative for Action on the Social Determinants of Health for Advancing Equity, WHO/HQ |

| Kumar P | Discussant in his role as chair of WONCA Rural South Asia |

|

Webinar 5: ‘Improving rural health information systems for health equity’, 15 December 2021 Chairs and rapporteurs: Theadora Swift Koller (WHO/HQ); Bruce Chater (Rural WONCA) Greeting by Anna Stavdal, President of WONCA |

|

| Hosseinpoor A | Using the Health Equity Assessment Toolkit to understand rural-urban inequalities |

| Stenberg K, Hedao P | Using ACCESSMOD to evaluate geographic and time barriers to health services, including examples around addressing snakebites |

| Bryce BA | Increasing access to health services in OECD rural regions |

| Nafula Wanjala M | Harnessing health information systems to strengthen health care in rural and remote areas |

|

Webinar 6: ‘Unpacking the causes and manifestations of rural health inequities: the use of mixed methods research’, 19 January 2022 Chairs and rapporteurs: Theadora Swift Koller (WHO/HQ); Bruce Chater (Rural WONCA) |

|

| Houghton N, Bascolo E | Addressing access barriers faced by rural communities in the Americas through participatory mixed methods analysis [case studies from Guyana and Peru] |

| Kotian SP | Demystifying the barriers to health services in rural areas using mixed methods research |

| Schaefer L | Understanding communities of deep disadvantage in the United States |

| Ruano AL | Bottlenecks and opportunities to have data on rural health better used on policymaking and programming |

|

Webinar 7: ‘Rural women and addressing inequities in health service coverage’, 24 February 2022 Chairs and rapporteurs: Theadora Swift Koller and Evelyn Boy-Mena (WHO/HQ); Bruce Chater (Rural WONCA) |

|

| Marwa M | Improving sexual and reproductive health services and GBV services for disadvantaged rural women |

| Raza A | Improving access to nutrition-related services amongst rural women |

| Mungo C | Tackling inequities in access to cancer prevention, early detection and treatment experienced by rural women globally |

| Emerson M | Provision of intercultural approaches to cancer services for rural Indigenous women |

| Gokdemir O | Capacity building of rural family doctors on gender responsive service delivery |

|

Webinar 8: ‘Innovations for equity-oriented health service delivery in rural and remote areas’, March 2022 Chairs and rapporteurs: Theadora Swift Koller (WHO/HQ); Bruce Chater (Rural WONCA) |

|

| Lkhagvasuren E, Ganbat B | Increasing organizational and social innovations through the ‘Health Equity Champions)’ project in Mongolia |

| Muneene D | Using Digital Health to reduce inequities in access and improve the quality-of-service capacity in rural areas |

| Keel S | Innovations for equity-oriented eye care in rural and remote areas |

CONDISI, Conselho Distrital de Saúde Indígena (General Coordination of Social Participation in Indigenous Health). GBV, gender-based violence.

Methods

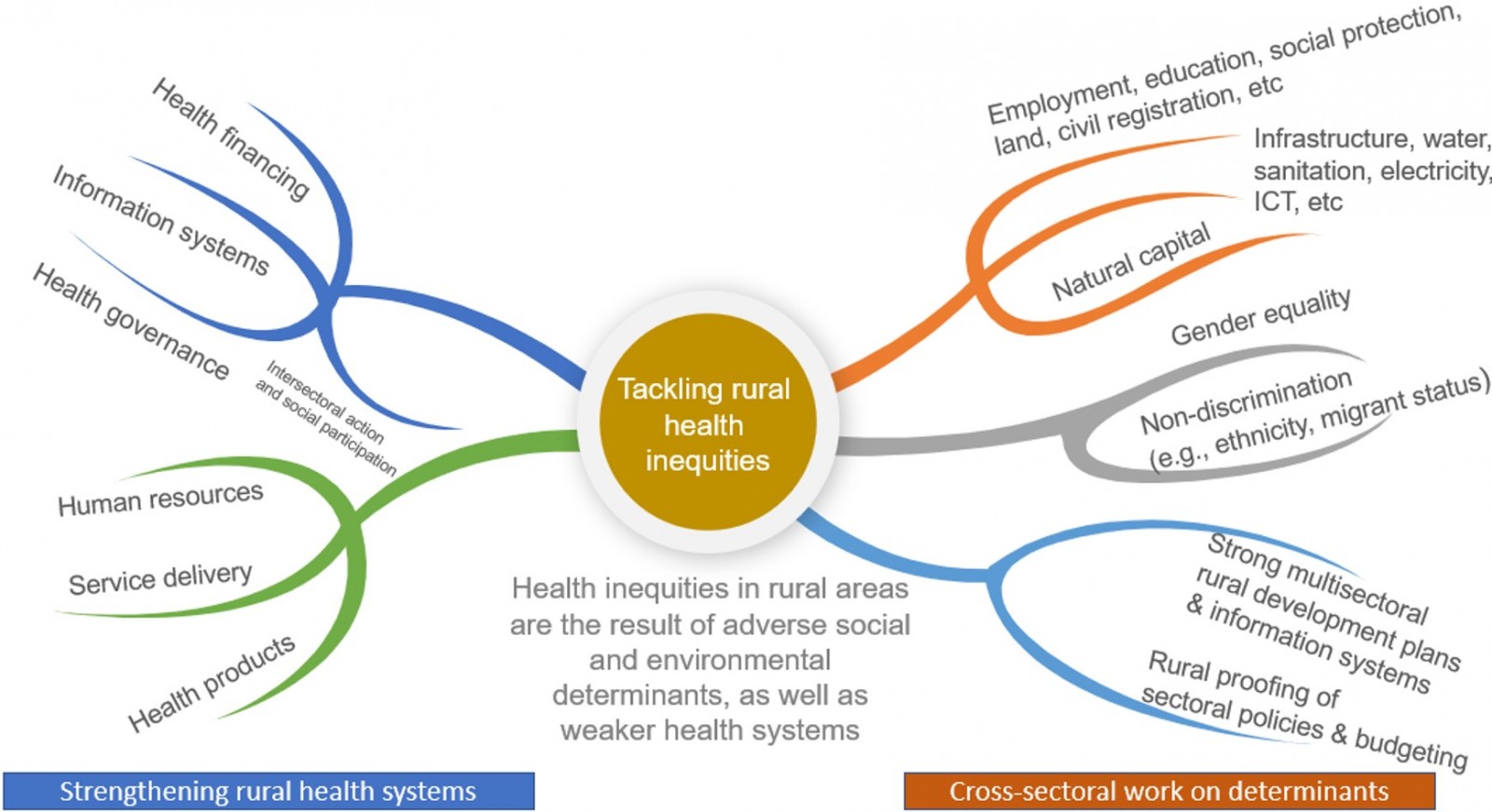

The framework underpinning the design of the webinar series drew on previous work by WHO12,13 applying a health-systems-wide and cross-sectoral action lens to rural health equity, as depicted in Figure 114.

Informed by the framework, the topics of the webinar series and speakers are summarized in Table 1. Not all topics of the framework could be covered due to resource constraints. Criteria for speaker engagement included relevant technical knowledge/expertise and practical country-level experiences on the topic, the capacity to speak in English or have interpretation into one of the official UN languages arranged, and availability at the time and date required (across time zones). Due attention was given to select speakers from different geographic regions, country income levels and gender/sexes. Thematic variation of inputs linked to the topic of each webinar was also considered. Specific attention was also given to recruiting Indigenous speakers, as 73% of Indigenous Peoples live in rural areas globally15.

All webinars were open to the public and recorded for parallel release on the WHO website, with the consent of the speakers. Each webinar was transcribed using automated transcription in Zoom. To enable the webinars to conceptually inform different WHO products, each transcript was then cross-checked with the recording and corrected for accuracy by WHO staff.

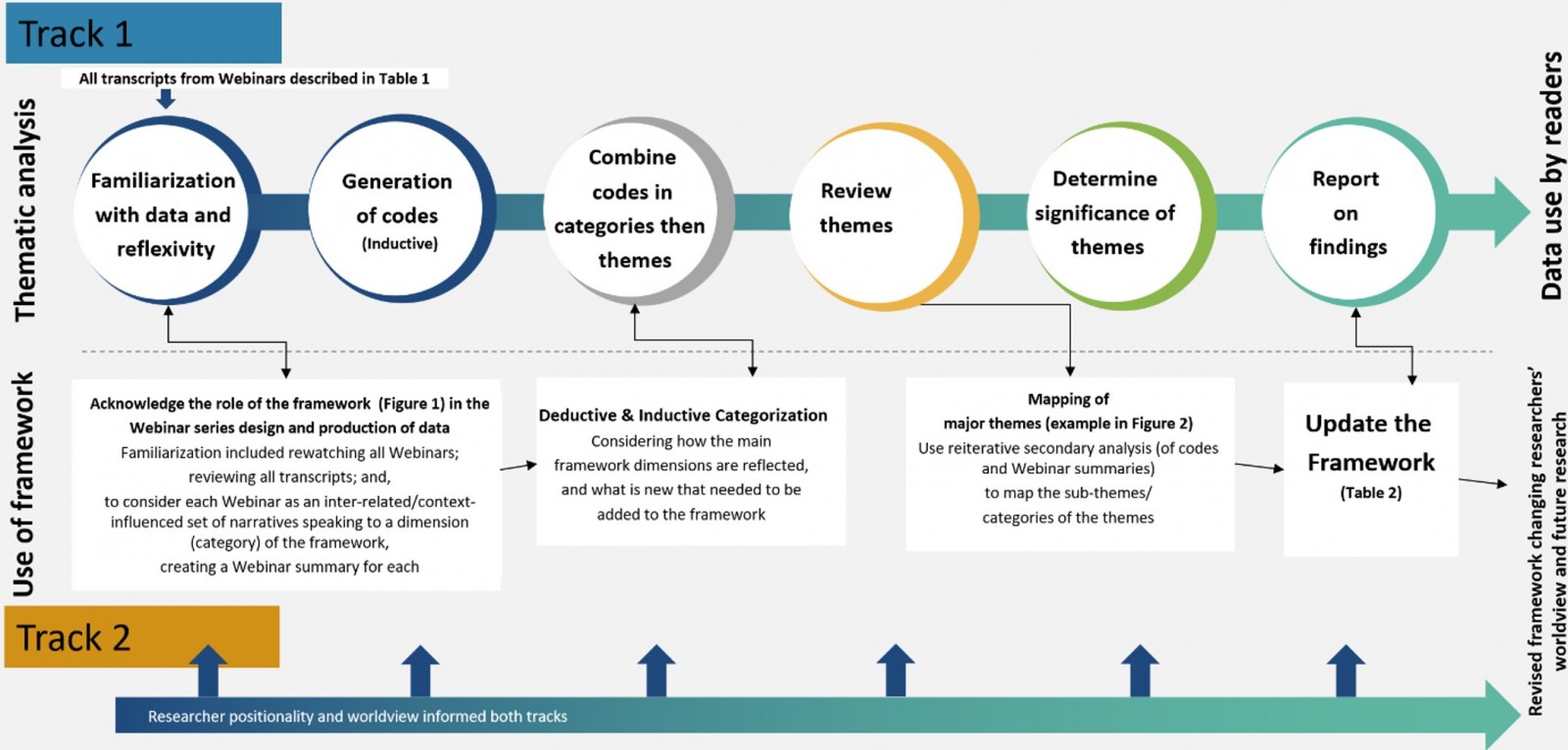

Following transcription, a framework-informed thematic analysis was undertaken (Fig2). Thematic analysis was considered by the authors as the appropriate method to respond to the research question, given the focus on experiences and views of webinar speakers. This approach drew on the six steps for thematic analysis of Clarke and Braun16, as well as recent work by Braun and Clarke17, to inform track 1. As a basis for inspiring track 2 and its interface with track 1, the lead author drew on the work of Pope and Mays on framework analysis18. In terms of positionality, both authors had roles in the design and execution of the webinar series, including for the selection of speakers and chairing. The first author has a technical background in health equity and has worked for WHO across a range of country contexts in supporting national health authorities. The second author, as both a GP in a rural area and an academic, has extensive experience in primary care in rural areas and coordinates with other GPs globally through the rural working party of WONCA.

To commence the two-track approach in Figure 2, the lead author further familiarized herself with the data, specifically by rewatching all webinars and reviewing all transcripts. She also applied a reflexive lens, acknowledging the role of the framework in influencing the data collection and also the interrelated and context-influenced nature of narratives within the same webinar. The data familiarization extended to producing narrative summaries for each speaker and then for each webinar in tables.

The lead author then coded the data (transcripts of the chairs, speakers and discussants/commentators). She then undertook a process of combining codes into categories, grouping the categories and then identifying the themes. The process of categorization was both inductive and deductive, as it both considered how the original framework used to design the webinar series was reflected in the data, while also gathering new insights from the data to create new categories (and subsequently inform the framework). Then, using the mapping function of NVivo v1.7 (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo)and drawing from both the coded data and the webinar summaries, she mapped and produced summaries for categories of themes and subthemes/categories. (See Figure 3 as an example output.) This was followed by further analysis of the data using an inductive and deductive approach (both serving to expand the broad framing on rural health equity issues originally used to design the series, while also adding to it more detail – the result was Table 2).

The lead author then produced the article manuscript with intent to writing it for both a policymaker and a research audience, with inputs/feedback from the second author. In the selection of quotes for the manuscript, due attention was given to thematic relevance as well as geographic and gender balance of speakers. As the webinar series had spanned local, national and global perspectives on issues and included specific case studies, the selected quotes reflect this intentionally as it enables readers to navigate across the levels of understanding and experiences of a given issue.

Figure 1: Representation of rural health equity that informed design of the webinar series.

Figure 1: Representation of rural health equity that informed design of the webinar series.

Source: TS Koller14.

Figure 2: Two-track approach to the framework-informed thematic analysis.

Figure 2: Two-track approach to the framework-informed thematic analysis.

Source: adapted by TS Koller from Clarke and Braun, and Pope and Mays16-18.

Ethics approval

As all information used in the article was already freely available in the public domain, ethical clearance was not required. Prior to submission, the draft article was shared with webinar speakers for whom quotes are featured, in case they wished to provide feedback.

Results

This section reports selected findings in relation to framing of rural health equity and implications for governance approaches. Narratives are identified by the last name of the speaker (as done in Table 1) given the nature of the data, with select usage of verbatim quotes from the webinar transcripts. It can be noted that the analysis incorporates narratives about a broad range of country contexts, including Australia, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Egypt, Finland, France, India, Japan, Kenya, Mali, Mongolia, Philippines, Slovenia, South Africa, Tanzania, Thailand, UK and the US.

Theme 1: Primary healthcare-oriented health systems strengthening are central for rural health equity

Across expert narratives, PHC-oriented health systems strengthening6 was identified as a priority for rural health equity. This was in keeping with the original framework for the series (Fig1), with the role of specific PHC strengthening levers6, or strategic and operational interrelated focus areas that can leverage action towards PHC goals, coming through strongly.

A persisting subtheme across the dataset was the role of the rural PHC workforce in enabling equitable access to health services, suggesting that any framework for rural health equity must give this dimension a central role. The attraction, recruitment and retention of generalist health workers in rural and remote areas, including through rural pipelines, clearly emerged, and WHO and partner guidance on ways to do this was shared2,19. Case studies of successful interventions were also shared. For example, Doumbia and Maiga described the Gao School of Nursing (EIG), a result of a public–private partnership that, since 2000, has shown considerable success in helping to fill health worker gaps in northern Mali. The EIG created a rural pipeline for nurses from northern areas, providing job opportunities for members of local communities while facilitating more equitable health service coverage. EIG graduates represented 78% of providers in the northern health facilities in 2019, with retention factors including scholarships and financial aid, marital status of women, working environment, proximity to the EIG (for continuing competencies development), allocation of on-call housing, and water point and solar electrification.

An example of a rural pipeline approach was also shared by Le Blanc from the Northern Ontario School of Medicine in Canada. As part of its efforts to attract rural youth, there is an explicit focus on attracting Indigenous youth, with a comprehensive approach:

It starts right in childhood, focusing on pathway programs, working with local science educators to develop an interest in health careers as a pathway, as well as building strong connections back with alumni and creating opportunities to see role models.

We have an admission stream in which an Indigenous admissions committee, which is chaired by Indigenous physician …, selects our applicants and we do have a focus on ensuring there's a particular population representative within our student body, which is about a 20% target for Indigenous trainees.

Additional health workforce subthemes included the working conditions and remuneration of the rural health workforce, including community health workers, how the health labour market can contribute to gender equality and social inclusion in rural areas, the generalist competencies and clinical courage (defined as ‘practicing outside of their usual scope of practice to provide access to essential medical care’20) of rural health workers, and the ongoing capacitation of health workers in rural and remote areas. The following quotes elucidate the linkages between gender inequalities and working conditions:

The formulation of health workforce policies in rural and remote areas really needs to acknowledge the pervasive gender dynamics and resulting occupational segregation. (McIsaac)

The community health worker workforce in Africa, for example, is more than three-quarters women, and 86% of those women do not receive a wage. So, it's time for a change … It's worth noting that when we look across the world and see where community health workers are paid and where they're not, it does not track with GDP per capita. Some of the poorest countries in the world, Liberia, for example, do pay these rural women. (Ballard)

Expert narratives across the series reflected the interdependent nature of subthemes within the PHC theme, suggesting that strengthening health systems in rural areas must account for the linkages, interreliance and synergistic nature of all PHC strategic and operational levers, and that a framework for rural health equity could benefit from emphasizing this. For example, the interactions between health workforce shortages and other PHC levers including models of care (including how referral systems work), physical infrastructure, and funding and resource shortages were unpacked in the narrative by Nafula Wanjala providing insights from her experience at a health centre in rural Kenya:

In theory, we had a catchment population of about 25,000. I was the only medical officer working there with one clinical officer and 16 nurses … After three months of working there, what happened was I realized we're not able to give the services that were necessary because despite us being a health center, we served as a referral centre to about 16 other dispensaries and three other health centers.

So immediately after they knew there was a doctor there, they began sending all their patients from the dispensaries and the health center to our health center as a referral center. But since it was a health center, we did not have a theater. We did not have any radiological services. And so there was so much we could not do, and we could not cover the hospital 24/7.

Expert narratives highlighted the subtheme of investing in innovations in service delivery in rural and remote communities. Wilson described how innovative partnerships with community groups and support networks for service delivery had emerged during the COVID-19 period in rural England, and the importance of systematically supporting/integrating these into the health system moving forward. Keel described efforts to tackle rural–urban inequities in eye health through service delivery innovations by Lions Outback Vision in Western Australia, which has provided a statewide teleophthalmology service linking patients in rural and remote communities to consultant ophthalmologists based in the state capital city. There is also a linked outreach component, as described by Keel:

Patients who after their telemedicine consultation require specialist care are booked in for an appointment at an upcoming outreach visit. And these outreach visits are multipronged and consist of visiting primary eye care workers who really play an instrumental role in improving the efficiency of referral and more targeted referral to the specialist services, but also ensuring ongoing care following treatment at the specialist services.

There's also periodic outreach specialist clinics that are set up in regional hospitals. And then there's also Lions Outback Vision Van … This vision van consists of three consulting rooms, and it includes quite sophisticated equipment and that enables the care of quite a significant range of eye common eye diseases such as glaucoma, diabetic, retinopathy and trachoma.

Theme 2: Addressing rural health inequities requires cross-sectoral work on social and environmental determinants

The theme of addressing determinants of health (in other sectoral domains and through integrated rural development planning) was emphasized in multiple expert narratives. Monroy emphasized that ‘a sectoral view is not enough when spatial scale matters’, and that the lack of an integrated approach to rural development could result in fragmentation and inefficiencies. Such inefficiencies and cross-sectoral dependencies are particularly evident when considering determinants of well-functioning health systems, such as water and sanitation, electrification, broadband, civil registration and roads. The example of Chile’s Rural Development National Policy was shared by Montero, who emphasized the importance of coordinated action across working ministries, under the umbrella of the policy and through engagement in a dedicated multi-stakeholder committee for rural development.

Multiple expert narratives and participant comments during the webinars stressed that integrated rural development was also necessary to account for rural communities’ main source of livelihoods globally, agriculture, and its role in rural health and wellbeing. The relevance of this was articulated by Kumar, a GP in India:

I can just say that not all diseases can be treated by just medicine. We need to focus on social determinants of health. Those who come with anxiety and depression because of lack of jobs, poverty, out of pocket expenditure, they won't feel better with medicines … Since most of our rural communities depend on agriculture, it's one of the most important areas to focus on.

The subthemes of poverty, lower formal education and literacy levels, gender inequality, food insecurity, lack of social protection, increasing safety and security issues, and lack of employment opportunities were identified from the dataset as key rural social determinants of health. Examples of how these influence health inequities in rural communities were provided across country contexts. For example, Bryce described how lack of economic opportunities in rural areas contributed to substance use in the US, and Mohan described how gender inequality exacerbates other determinants of health inequities in rural Rajasthan, India. Chater described how rural health workforce strategies that support rural pipelines contribute to addressing some of these determinants while also addressing workforce shortages.

Additional determinants particularly salient to rural areas were also identified as subthemes from the expert narratives, with these including the need to address land ownership and land inheritance issues, employment in agriculture, outmigration and weakening of social fabric in rural areas, biodiversity loss and ecosystems disrupted by climate change, Indigeneity and connection to the land, histories of colonialization and structural discrimination, inadequate emergency/disaster preparedness and response in rural areas, and socio-spatial disinvestment or continued weak investment in rural services and infrastructure (eg impacting roads, public services, and information and communications technology/broadband capacity). Koller (in the joint presentation by Koller, Beltchika and Mane) made the explicit links between these determinants, human rights and social fractures in rural areas:

Lack of public services or the inadequacy of public services in rural areas also jeopardize key rights such as the right to a healthy, adequate and nutritious diet; the rights to education, health, social protection … Those inequalities and inequities also increase the risks of violence and tensions in the rural communities.

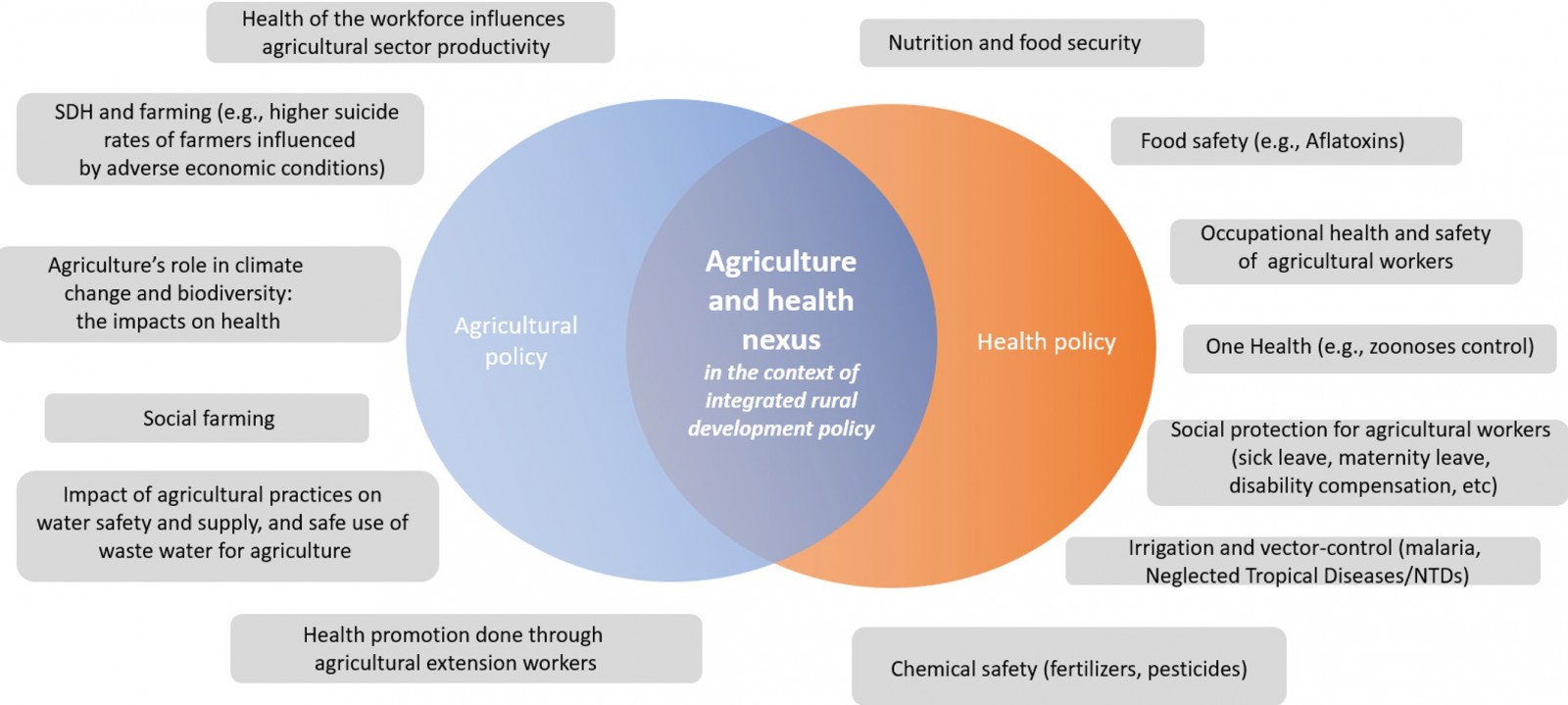

The subtheme of agriculture as a determinant of health was well covered by the dataset, as it had been the subject of a dedicated webinar. The links between health and agriculture were noted by Mugambi, who described how food and agricultural policy and practices can impact communicable (eg malaria, neglected tropical diseases) and non-communicable diseases (eg malnutrition, obesity and diabetes), while highlighting that foodborne illnesses and livestock-related zoonoses can be major drivers of ill health in both rural and urban populations. Mugambi also described how ill health in rural areas negatively impacts agricultural sector productivity. The role of agriculture in driving rural health inequities was further elaborated in expert narratives covering applications of One Health approaches and poverty reduction (Pica Ciamarra); occupational health safety and services (Ivanov), the role of the rural health workforce in galvanizing local and community intersectoral action for health with the agricultural sector in Kenya (Mugambi), and a cross-sectoral initiative in Slovenia (Programme Mura) bringing together the health, agriculture and development sectors for improved health, labour market and local economic outcomes (Buzeti). For the latter, the specific role of agricultural extension workers for health promotion was explained by Buzeti:

Agriculture extension service took on a lot of health promoting activities, being for safety at the workplace but also being for the short supply chain development and bringing the local organic production produce into the kindergartens, into other public institutions in order to improve dietary habits. That's how we actually have a health-in-all-policies approach with a very strong equity focus.

Figure 3 gives an overview of the subtheme components emerging from the dataset related to the agricultural and health policy nexus.

In understanding social and environmental determinants in rural areas, the expert narratives pointed to ‘history’ as a subtheme, suggesting the need for a historical lens that examines both spatial socioeconomic development alongside social exclusionary processes linked to the distribution of power and resources. While it is difficult to reflect history itself in the framing of rural health equity, expert narratives conveyed that it cannot be absent. For example, Schaefer described how 80 of the 100 most disadvantaged places across income, health and mobility in the United States of America are rural counties, and the history of these counties was a determining factor:

When we use a regression model to predict disadvantage in the 21st century in the United States, we are able to predict with quite a bit of precision that simply based on the rate of enslavement in 1860. So this told us a lot about the importance of both of focusing on rural communities, which are deeply understudied in the United States, and also understanding how much history matters.

In the coverage of the historical aspect, expert narratives also stressed the importance of understanding histories of resilience, self-determination and community assets (with this identified as an important subtheme). For example, Peachey described how community-controlled health services and a significant increase, over the past 25 years, in the number of Indigenous health workers have contributed to improved health outcomes for Aboriginal Australians. Emerson described the relevance of intercultural care that is done by Diné/Navajo Indigenous Peoples in the USA, including traditional health messaging grounded in their matrilinear worldview, and acknowledgement of the important role of Diné women in providing leadership for health.

Figure 3: Overview of findings related to the agriculture and health policy nexus.

Figure 3: Overview of findings related to the agriculture and health policy nexus.

Source: TS Koller, based on the thematic analysis. SDH, social determinants of health.

Theme 3: Governance approaches should promote rural health equity

Within the theme of ‘governance for rural health equity’, the subtheme of ‘rural proofing’ was explored through a dedicated webinar. Rural proofing is a governance intervention entailing the systematic application of a rural lens across policies, programs and initiatives, to ensure that they are adequately accounting for the needs, contexts and opportunities of rural areas21-23. Yet, the need to apply a rural lens in health sector policymaking and programming was a theme that persisted in expert narratives across the series. Important insights were provided on lessons learnt from rural proofing in different country contexts, including South Africa and the UK. Rensburg described how rural proofing in South Africa had contributed to the inclusion of sparsity indicators in the resource allocation decisions in provincial and district funding formula, as well as influenced health workforce policy. Drawing from his experience in England, Wilson explained how rural proofing can help manage rural challenges such as distance from services, lost economies of scale, costs and infrastructure gaps, while also optimizing overarching service outcomes. Related to applying a rural lens in programming, the need to adapt disease-specific policies and programs for rural areas was poignantly expressed by Mungo, who explained that, of all women who die from cervical cancer each year, the majority come from rural areas of countries that have been unable to provide preventative measures.

Within the governance theme, expert narratives also pointed to other subthemes such as the need for policymaking and programming for rural health equity to be based on local community needs, reflect the heterogeneity within rural populations, engage the community in their design, and account for traditional health practices and community assets for health from the very start of policy formulation. The subtheme of spatial diversity across rural communities, from semi-rural to very remote, from mountainous to island, was identified as relevant to consider in health programming, as were the specific needs of populations including people experiencing poverty, women, older persons, youth, Indigenous Peoples, ethnic minorities, herders and nomadic peoples, migrants and refugees. Lkhagvasuren and Ganbat described a Mongolian government initiative that solicited provincial health centre proposals for local action on health equity, based on needs assessments of populations at risk of being left behind such as persons lacking registration in a local area, remote area herders and uninsured people. Marwa described a project for first-time young mothers in Tanzania’s rural Kigoma region, a region with a considerable refugee population. Goklish and Sinquah highlighted special measures for and targeting of older persons in multigenerational households in the White Mountain Apache Tribe’s response to COVID-19 in the USA.

Enabling governance for rural health equity to be evidence-based, informed by strong information systems, was a key subtheme. Expert narratives suggested a continued need for strengthening of health information systems to allow for health inequality monitoring across health indicators by rural and other dimensions of inequality, allowing also for trend analysis. Hosseinpoor described how the WHO Health Equity Assessment Toolkit24 could contribute to this. Stenberg and Hedao described the role of spatially responsive analyses for acute health needs in rural areas on which saving lives depended on urgent receipt of appropriate care, such as emergency obstetric care and snakebite treatment. They described how the ACCESSMOD25 tool enables five different types of relevant analysis: accessibility analysis, geographic analysis, referral analysis, zonal statistics and scaling up analysis. Nafula Wanjala described how – deriving from her experience in managing facility-based data collection in rural Kenya – data for improving health services should be robust but simple, owned by all relevant actors, integrated, contextualized and ‘tell a story’ for closing coverage gaps and enhancing quality. Houghton and Bascolo as well as both Kotian and Schaefer explained the role of assessing barriers to health services and using participatory research methods. Ruano called explicitly for greater attention to participatory approaches:

Rural populations and their data need to be put at the centre of their development It is important for us to reflect on the level of participation that we're fomenting …, if we're really just asking communities to participate in a tokenist way, or if we're actually doing the work to empower them and give them enough tools and enough capacity to co- decide with us …

Within the governance theme, budgeting and investing in rural health systems was an additional subtheme. Expert narratives suggested that decisions could go beyond health sector budget allocation formulas to take a wider cross-sectoral view. This would entail looking at the multiplier effect of investments for health on local economies and labour markets in rural areas. It also entails consideration of a wider economic system that underpins the resilience, dynamism and attractiveness of rural areas, and is grounded in an explicit decision to support balanced territorial development. Different experts highlighted how health services in rural areas can keep/make them places where people want to live and integrated economies can thrive. Ballard shared that investments by a health system in community health worker programs can yield significant returns through saving lives and creating rural employment. Pica Ciamarra drew the links between adoption of One Health approaches by livestock holders and its potential impact on breaking the disease-driven poverty trap through improved productivity and profitability, while also protecting the world at large from costly public health threats (including pandemics) caused by zoonoses. Chater provided an example of the localized economic and labour market benefits of integrated social and health care:

We've talked about the policy frameworks that support all this … about making sure those policy settings are right and localizing economic benefit. We had one of our doctors at a conference in Albuquerque talking about the massive benefit of having aged care in his town and the economic benefits of having extra health workers, extra aged care workers, and those people still in their communities. So making the most of that, rather than seeing it as a burden.

Rensburg highlighted that, while this cross-sectoral view of cost and benefits is an opportunity, it is also a challenge in the current context:

I think the biggest challenge for us is really just to look at all of these intersectoral challenges and how we can better link health not just to healthcare, but also to articulate health as an enabler of development, as something that can contribute to addressing a number of different SDGs [Sustainable Development Goals].

Drawing on the findings from the thematic analysis, an updated version of the framework for rural health equity used to design the webinar series is shown in Table 2, incorporating insights from the expert narratives.

Table 2: Updated version of the framework for rural health equity used to design the webinar series, incorporating insights from the expert narratives

| Pathway 1: Tackling inequities in health service coverage and quality experienced by rural and remote communities | Pathway 2: Advancing intersectoral action for health and health equity in rural and remote areas |

|---|---|

|

|

Cross-cutting themes:

|

|

Discussion

Through its focus on framing rural health equity, this thematic analysis of 51 expert narratives identified insights for informing future work on policymaking and practice in three domains: PHC-oriented health systems strengthening, cross-sectoral action on determinants, and governance approaches.

The thematic analysis evidenced that framing of rural health equity issues needs to account for PHC-oriented health systems strengthening issues in a way that highlights their indivisible, interrelated and synergistic nature, taking a system-wide approach. This is in alignment with systems-thinking approaches that underpin political declarations on universal health coverage5, and reviews of rural health tools, frameworks and approaches26-28. It is also in alignment with findings from recent country-specific assessments to identify barriers to health services in rural and remote areas29,30 that show, for instance, how too-limited competency allocated to primary care practitioners can influence barriers linked to waiting times for secondary level care, financial barriers or financial hardship due to out-of-pocket expenditures, and barriers related to opportunity cost and transport for people living in rural areas.

The thematic analysis clearly pointed to the need for framing rural health equity to account for social and environmental determinants of health and acknowledge the role of history. This is in keeping with literature about the health system being an open system, influencing and influenced by the context in which it operates31. Being open, health systems of rural areas are interdependent on the wider rural development context, as described in the findings from this thematic analysis.

The need for cross-sectoral approaches to solving rural workforce shortages has been highlighted by the WHO guideline on health workforce development, attraction, recruitment and retention in rural and remote areas2 as well as work by Rural WONCA on rural pipelines19. This proportionate focus on the determinants of rural health equity is also in keeping with White’s rural health framework32, and the work of knowledge hubs such as the Rural Health Information Hub in the US, through the Rural Health Equity Toolkit33 and the accompanying Social Determinants of Health in Rural Communities Toolkit34. In addition, it is reflected in national strategies on rural health such as that of the New Zealand government35. The thematic analysis findings elucidated that rural health inequities must be seen through the lens of history/time and the confluence of both spatial and social inequalities in power and opportunities, synergizing with Krieger’s description of ecosocial theory and people’s health36. Krieger highlights the importance of understanding conceptually the ‘multilevel spatiotemporal processes of embodying (in)justice, across the lifecourse and historical generations’. Histories of colonialization and discrimination on different grounds, as well as histories of land use, regional and sectoral economies, as well as biodiversity loss and climate change, cannot be unlinked from rural health inequities today. Health policies and programming must account for, operate in and contribute to transforming these historical contexts.

The thematic analysis findings have illustrated ways in which governance influences rural health inequity. As described in the previous section, findings shed light on governance issues such as inter- and intra-sectorial policy and programming coherence, effective rural-proofing mechanisms, evidence-based decision-making drawing from strengthened equity-oriented information systems, ground-up participatory decision-making approaches, rights-based governance (including for self-determination), and greater accountability for redressing socio-spatial inequities and optimizing rural communities’ assets.These findings suggest that unlocking rural health inequities will require the study of government commitments, governance mechanisms, and capacities to effectively implement measures for territorially balanced development and area-based strategies for equity within and between territories. As such, political science, as a field of study, offers important insights for tackling rural health inequities.

The thematic analysis illuminated multiple entry points where further research could be beneficial for rural health equity. These spanned the levers for PHC-oriented health systems strengthening. For example, the need for continued implementation research on building the cross-cutting capabilities of rural health systems and communities for adopting digital innovations was clearly identified. An opportunity is also evident for case studies and comparative analyses of country experiences in domains such as rural proofing of health policies, and social accountability in medical education for rural Indigenous health workers, among many more. Regarding wider determinants of health, further research can be done on whole-of-government approaches to tackling rural health inequities, both nationally through cross-sectoral policy alignment and locally through local action plans, grounded in a context-specific and rural stakeholder-informed understanding of the causal pathways by which rural health inequities are generated. More research could also be done to understand the social and economic multiplier effects of public service provision in rural areas, and to consider how weights for such investments account for their contribution to the attractiveness and resilience of rural areas.

With regard to limitations of the research, the original framework used to design the webinar series14) covered more issues than were reflected in the eight topics selected for the series. While covering additional rural health equity topics in depth through dedicated expert speakers would have been salient, it was not possible due to human and financial resource constraints at the time. The eight webinar topics were jointly agreed by co-organizers following deliberation on their operational relevance for the target audience (see Methods). An additional limitation was that the webinar series included very few speakers or examples from countries experiencing humanitarian crises, where rural populations face particularly aggravated risks for health and wellbeing, thus underlining the need to have these voices better integrated into global work on rural health equity moving forward.

Conclusion

Across the world and where information systems allow for appropriate disaggregation, health and health service coverage indicators are often worse among rural populations for many health conditions37. This article has reported selected findings from a thematic analysis of 51 expert narratives available in the public domain in an eight-part webinar series on rural health equity. Through the focus on governance for rural health equity approaches, the findings have relevance for the further design of policies, programming, monitoring and evaluation for rural health equity by national authorities, as well as for the activities of researchers, WHO, Rural WONCA and partners.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all speakers who took part in the webinar series, as their contribution of time and knowledge made this work possible. The authors also thank WHO colleagues Pramila Shrestha, Susana Gomez and Claudia Quiros as well as members of Rural WONCA for their contribution to the organization of the webinars on which this manuscript is based, and WHO colleagues Hortense Nesseler and Pramila Shrestha for their work in cleaning and cross-checking the transcriptions against the webinar recordings. Special gratitude goes to Shannon Barkley, formerly with the WHO PHC Special Programme, for her support to launching the series as part of the WHO and WONCA workplan; as well as additional WHO, OECD, International Fund for Agricultural Developmentand Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations colleagues who collaborated in either being or identifying speakers. In their capacity of PhD supervisory team to TSK (who is conducting part-time PhD studies in Applied Health Sciences at the University of Aberdeen, alongside her WHO employment), Lucia D’Ambruoso, Aravinda Guntupalli and Philip Wilson provided methodological inputs important to the thematic analysis and reviewed the first draft. Lastly, gratitude goes to Alia El-Yassir and Erin Kenney for support for the publication of the findings.

Funding

Funding for the Rural Health Equity webinar series and the thematic analysis came from the Government of Canada grant to WHO ‘Strengthening local and national Primary Health Care and Health Systems for the recovery and resilience of countries in the context of COVID-19’ (headquarters allocation for the Department of Gender Equality, Human Rights and Health Equity).

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

This article represents solely the views of the authors and in no way should be interpreted to represent the views of, or endorsement by, the World Health Organization. The World Health Organization shall in no way be responsible for the accuracy, veracity and completeness of the information provided through this article.