Introduction

Rural populations face inequitable access to primary healthcare services and are increasingly challenged to sustain a sufficient healthcare workforce1-3. Limited access to primary care contributes to higher morbidity and premature mortality due to missed health screenings, fewer wellness opportunities, and treatment delays4-7. Rural healthcare access problems are complicated by longer travel distances and disproportionately higher patient-to-provider ratios8. Moreover, in the US, researchers anticipate losses in the rural physician workforce of 23% by 2030, emphasizing a need for a robust pipeline of new rural healthcare providers9-12. Simultaneously, the demand for rural health care will increase because of the comparatively larger proportion of older adults living in these communities, whose advancing age will further strain the capacity of the primary care system13.

Despite the strain in the supply of physicians in the rural primary care workforce, there are encouraging trends in the rapidly increasing numbers of nurse practitioner (NP) graduates12,14,15. NPs have advanced clinical education, are qualified to provide primary care services, and are more likely to practice in rural communities than their physician colleagues5,14,16,17. The complexity and quality of primary care provided by NPs are equitable, and in some cases superior, to those of physicians in terms of patient outcomes and satisfaction16,18-23. In 2016, NPs represented 25.2% of the rural healthcare provider workforce in the US, an increase from 17.6% in 200814. In 2023, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated NP workforce growth of more than 46% between 2023 and 203324,25. This dramatic expansion in the number of NP graduates is shifting the configuration of the primary care workforce15,16,26,27. Unfortunately, estimated turnover rates for NPs are alarming, nearly twice that of physicians28-30. Yet there is a paucity of literature about the factors shown to influence turnover rates among rural NPs28,29,31.

New NP graduates often experience a difficult transition to practice when their faculty mentors are no longer available32. This is especially true for rural NPs, whose experiences of transition to practice are challenged by staffing shortages and healthcare-provider turnover33-37. Rural NPs are significantly more likely than non-rural NPs to be the sole provider in their community or have only one or two other providers in their practice setting38. They also serve populations challenged by higher rates of morbidity and mortality, and inequities in social determinants of health5,33,36,39,40. Rural NPs practice at greater distances from interdisciplinary networks and specialty referral sources33,34,41. Furthermore, rural NPs are often isolated by gaps in access to telehealth and remote consultation, as rural areas are twice as likely to lack broadband services3,8.

Postgraduate residencies are competitive, uncommon, and often inaccessible for new rural NPs42,43. This is important, because the quality of early career experiences with supportive mentoring impacts NPs’ intentions to turnover17,28,29,31,32. The unique complexities of NPs’ early career experiences in rural health care warrant a discipline-targeted research effort, specific to the rural context, where there may be less interprofessional collaboration and mentoring support5,27,29,31,44-46.

Research question and aim

The question driving this review is ‘What is the current state of the science regarding NPs’ early career experiences in rural healthcare practice?’ We synthesized the scholarly literature about NPs’ early career experiences in rural health care and identified the gaps in the literature for future research.

Methods

We applied Whittemore and Knafl’s five-step integrative review (IR) framework47 to derive a comprehensive description of NPs’ early rural healthcare practice experiences including: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation. Integrative reviews are well suited for exploring abstract but related concepts, analyzing and synthesizing diverse research methodologies, and developing conceptual models when there is scarce literature about a complex social phenomenon in a given context48-51. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines informed the approach to reporting this review52.

Search strategy and selection criteria

Four library databases were searched: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and CINAHL. The following key terms were used: 'new graduate', 'postgraduate', 'novice', 'beginner', 'early career', 'nurse practitioner', 'advanced practice nurse', 'advanced practice registered nurse', 'rural', 'remote', 'frontier', 'experiences', 'adapting', 'adjusting', 'belonging', 'integrating', 'retention', 'burnout', and 'turnover'. The bibliographic search was initiated after standardized medical subject headings (MeSH) were applied. With collaboration and oversight of a well-experienced research librarian at the lead author’s institution, appropriate truncation, Boolean operator, and indexing techniques were utilized for each database. No time delimitation was applied.

Inclusion criteria

Article inclusion criteria were as follows: full text; in English; involved exclusively new NPs, stratified for rural primary care practice; and an empirical report (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed method) or a theoretical article focused on the perspectives, social processes, or related phenomenon of new rural NP experiences. Unpublished or non-peer-reviewed documents, gray literature, secondary sources, abstracts, poster presentations, and opinion papers were excluded.

We defined ‘primary care setting’ as the patient’s first point of contact with the healthcare system, where healthcare needs are assessed, and comprehensive services are delivered in the context of an ongoing patient–provider relationship. Additionally, primary care is where basic health screenings are provided, and common acute or chronic health challenges, disabilities, health behaviors, and health risks can be evaluated and managed2,36,53. ‘New’ or ‘early career’ NPs were defined as recently graduated NPs in their first 6 months to 5 years of practice54,55. ‘Experiences’ were defined broadly as NPs’ actions, psychological perspectives, sociocultural interactions, and professional or personal processes conceivably related to rural healthcare practice. Definitions of ‘rural’ vary considerably in research studies56,57; therefore, publications met rural criterion if they were defined as such by their respective authors.

Study selection process

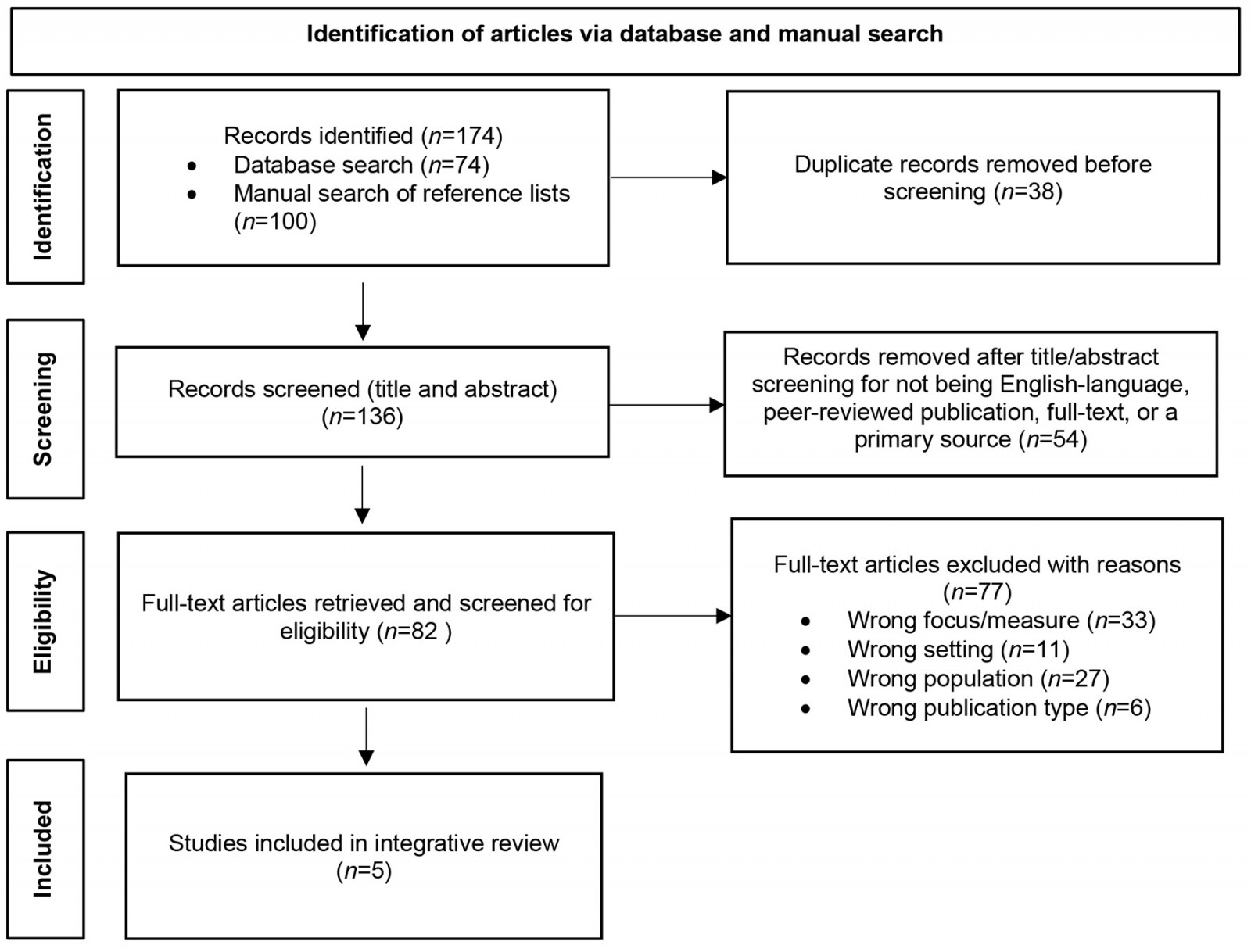

The modified flow diagram in Figure 1, informed by the PRISMA model52, depicts the process used to review and select relevant studies. Seventy-four articles were retrieved from the databases and exported into an electronic reference manager. The first author manually searched the 74 reference lists of retrieved sources for additional relevant articles and identified 100 additional articles not captured in the database search, yielding a total of 174 articles in the first stage of the literature search. Duplicates were removed, resulting in 136 articles to screen for English texts, peer-reviewed publications, and full-text articles. Subsequently, 54 articles were removed from the screening stage (Fig1). A total of 82 articles were assessed for eligibility. Only five studies met the inclusion criteria of the literature search.

Figure 1: Modified PRISMA flow diagram of article selection process.

Figure 1: Modified PRISMA flow diagram of article selection process.

Data evaluation and analysis

We developed an evaluation tool to appraise the quality of each source, including data about the setting, population, and purpose; alignment of research questions with a theoretical framework and study design; study adherence to ethical guidelines; clarity and rigor of data collection and analysis; and summary of findings and their relevance to the proposed research. Components of the data extraction and evaluation tool were adapted and combined from McMaster’s qualitative research guidelines58, Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ)59, and suggestions from several literature review resources47,48,52,60,61. Two reviewers (CMS, AMH) independently extracted, documented, appraised, and reviewed the selected components from each article and discussed discrepancies until consensus was reached. The evaluation did not include a scoring component, because most studies were qualitative, and evidence ratings are not standardized for dissimilar research designs47,60.

In keeping with Whittemore and Knafl’s (2005) framework47 and PRISMA guidelines for processing and reporting52, articles were independently reviewed (CMS, AMH) for their identifiable themes and contributive value to the literature review objective. Findings from the selected studies (n=5) were extracted, characterized, and compiled into matrices (data reduction)47. Characteristics of the studies and relevant findings are presented in Table 1. Matrix data were then reorganized into tables according to common themes and experiences to promote the visualization of patterns and relationships across sources (data display)47. Repetitive and significant patterns were extracted, summarized, categorized, and compared between studies. The categories were analyzed for cogency and arranged into abstracted clusters.

Table 1: Characteristics and relevant findings of sources selected for literature review

| Author(s), publication year and country | Purpose | Design and participant sample | Findings relevant to literature review objectives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conger and Plager, 2008, US | To describe the lived early career experiences of APNs in the context of the theme ofconnectedness versus disconnectedness in rural healthcare practice. | A secondary analysis of an interpretive phenomenology study; five focus groups and 14 individual interviews (30 total participants); master’s-prepared APN graduates with ≥1 year practice experience; 76% were NPs; 87% practiced in rural settings. | The central theme, Rural Connectedness v Rural Disconnectedness,describes the rural early career APN experience of developing support networks, connecting with their rural community, building relationships with urban centers, and utilizing technology to cope with the constraints of rural healthcare practice and mitigate the effects of isolation. Developing these relational elements resulted in the new APNs’ experience of rural connectedness. In contrast, the absence of these social connections was associated with APNs’ perceptions of loneliness, isolation, intentions to leave the community, and rural disconnectedness. |

| Gonzales et al, 2022, US | To describe the experiences and perceived needs of early career NPs during the transition-to-practice period. | A quantitative descriptive survey of Nebraska NPs, currently practicing in primary care and <3 years post-graduation; 87 participants; 44% of participants were rural; and 52% in their first year of practice. |

New rural NPs scored similarly to non-rural NPs in their recalled perceptions of self-confidence and clinical preparedness for providing primary care at the beginning of their first year of practice and 3 months later. These scores improved significantly with time in both groups. Still, an overwhelming majority (85%) of all participants would have been interested in pursuing a postgraduate residency opportunity to aid their transition-to-practice experience if one had been accessible. New rural NPs differed significantly from non-rural NPs in their reported access to medical and social referral sources for their patients. Moreover, rural NPs had limited opportunities to engage in quality improvement projects or professional committees, and fewer practice ownership opportunities than non-rural NP respondents. |

| Kaplan et al, 2023, US | To investigate rural NP residency programs’ characteristics and impact on NP transition-to-practice experiences and retention in rural primary care. | A qualitative, descriptive study of rural NP residency programs; semi-structured interviews with 8 NP residents, 12 administrators, and 4 clinic personnel. 12 of the 20 rural residency programs participated (60%). |

New rural NPs were motivated to participate in rural residency programs for the following reasons: lacking confidence or desiring more rural clinical experiences, rural job security or loan repayment incentives, preferring the rural lifestyle or desiring to sustain existing rural social connections. Research studies spanning a broader timeframe than 12–15 months are indicated to determine the impact of rural residency programs on retention in rural primary care. |

| Owens, 2018, US | To explore RNs’ lived experiences with transitioning into their rural FNP professional identity, and how new professional identities developed during their first year of rural primary care practice. | A phenomenological study of 10 master’s-prepared FNPs from one rural Midwestern university during the first year of clinical practice were interviewed twice, once at 6 months and again at 12 months. All participants had prior personal and professional rural experiences, including RN experience and FNP student rural clinical rotations. |

Transitioning into a new professional identity and acquiring advanced rural practice skills were scaffolded by pre-existing rural clinical experience. Ongoing involvement in professional development and continuing education opportunities were essential to providing safe, high-quality, evidence-based care. Feelings of stress, overwhelm, and anxiety were noted initially but resolved over time. Mentoring, supportive orientation experiences, and positive interpersonal interactions with patients and colleagues enhanced transitioning experiences and work satisfaction. Professional identity development was characterized by a sense of clinical competence and autonomy to provide high-quality patient care and perceiving oneself as a valuable contributor to improved primary care access for rural populations. |

| Owens, 2021, US | To explore the experiences of rural NPs during their first year of rural practice and their perceptions of professional identity formation while transitioning from RN to FNP. | A phenomenological study of 12 rural FNPs (42% master’s-prepared and 58% doctoral prepared), in the first year of rural primary care practice. Graduates from three Midwestern universities were recruited, a broader catchment area than the prior Owens (2018) study. Individual interviews occurred twice during the first year of practice, at 6 and 12 months, respectively. All participants had a pre-existing rural health background, having worked as a rural RN before becoming an FNP. |

Rural FNP skills, knowledge, roles, and responsibilities were built upon past rural RN experiences and also depended on ongoing professional development and continuing education. Positive, collaborative interactions with other providers, interprofessional team members, and patients mitigated feelings of isolation. These relationships also supported the learning, socialization, and formation of a professional identity. Incentives to work in the rural setting included a passion for lifelong learning, job availability, loan repayment programs, preferences for autonomy and full practice scope, preferences for the rural healthcare setting and lifestyle, and a desire to improve rural residents’ access to primary healthcare services. FNP professional comportment, a unique concept in this study, was characterized as respect for and collaboration with interprofessional team members, engagement in full practice scope and practice autonomy, and accountability for providing safe, ethical, patient-centered care. Successful FNP professional identity formation resulted in perceptions of competence, confidence, and satisfaction, with no intention to turnover. |

APN, advanced practice nurses. FNP, family nurse practitioner. NP, nurse practitioner. RN, registered nurse.

Results

The literature review yielded five articles that specifically addressed the early career experiences of rural NPs, including three phenomenological studies62-64; one descriptive qualitative study42; and one descriptive, quantitative program evaluation65. With one exception63, all studies had been conducted in the previous 6 years42,62,64,65, suggesting that this substantive area is relatively novel in the rural healthcare workforce literature.

Summary of the evidence

Our findings indicated that studies about new NPs’ experiences in rural healthcare practice were heavily focused on the recruitment, preparation, and transition-to-practice phases of NPs’ early careers (0–15 months of practice)42,62,64,65. Sample sizes were consistent with the study designs. The qualitative studies included individual interviews and focus groups, and sample size range was 8–23 NPs42,62-64. There were 87 NP participants in the quantitative program evaluation65. All five studies were conducted in the US.

Common themes

Three themes emerged from the analysis: trajectory of early career practice for rural NPs (Table 2), commitment and persistence of new rural NPs (Table 3), and adaptive and maladaptive early career factors for rural NPs (Table 4). Each main theme (Tables 2–4) comprises two or three subthemes.

Trajectory of early career practice for rural nurse practitioners

The first theme was that there is a particular trajectory of new rural NPs’ early career experience. The trajectory has three distinct yet iterative phases: preparing for rural healthcare practice, transitioning to rural healthcare practice, and adapting to and sustaining rural healthcare practice (Table 2).

Table 2: Early career trajectory of rural nurse practitioner practice

| Early career phase | Citation(s) | Synthesis of primary sources |

|---|---|---|

| Preparing for rural healthcare practice | Conger and Plager, 2008 | An important aspect of preparing for rural clinical practice was providing a rural emphasis in the NP educational program, including rural placements for clinical rotations. |

| Gonzales et al, 2022 | New rural and non-rural NPs in Nebraska had similar mean scores measuring their perceptions of preparedness to provide complex primary care. | |

| Kaplan et al, 2023 | NP postgraduate residency programs provided new rural NPs an opportunity to gain additional rural clinical preparation and extended mentoring support. | |

| Owens, 2018, 2021 | Prior rural RN experience was considered foundational for further advancing rural NP clinical judgement, skills, and professional comportment. | |

| Transitioning to rural healthcare practice | Gonzales et al, 2022 | Mean scores of NPs’ retrospective perceptions of confidence and preparedness for practice improved after 3 months of initiating clinical practice. Yet 85% of respondents would have been interested in pursuing a postgraduate residency program to support their transition to practice had one been available. Teaching new graduates how to develop a community-specific support network would have benefitted them in their transition-to-practice period, including how to make referrals for medical and social services in the rural setting. Ensuring quality mentorship and orientation experiences and promoting collaborative relationships with experienced healthcare providers in proximity to new NPs is critical to successful transition experiences. |

| Kaplan et al, 2023 | Rural NP postgraduate residency programs provided structured curricular and professional networking support for the first 12–15 months of the early career and were designed to foster workforce retention during the transition-to-practice phase. | |

| Owens, 2018, 2021 | Rural educational experiences, including rural theory courses and rural clinical rotations, marked the beginning of the transitioning process and continued throughout the first year of practice. Initial feelings of stress, isolation, and anxiety improved as supportive relationships were established over time. Other factors that characterized a successful transition to practice included participation in an NP residency or mentoring program, involvement with interprofessional teams, access to continuing professional development and learning opportunities, perceived value in learning about and providing care for rural populations, and establishment of the NP professional identity. | |

| Adapting to and sustaining rural healthcare practice | Conger and Plager, 2008 | Supportive clinical relationships and integration into the rural community contributed to a sense of connectedness and resourcefulness, mitigating the effects of professional isolation. Conversely, a higher turnover intention in new rural NPs was attributed to feelings of isolation, lack of access to collegial relationships or mentors, lack of support staff and electronic support, and disconnectedness in the rural healthcare setting. Rural career survival was enhanced when NP graduates advocated for and developed their own early career support systems. |

| Gonzales et al, 2022 | Compared to non-rural NPs, rural NPs reported fewer opportunities for engagement in professional committees and quality improvement projects, and were less likely to be invited to ‘buy in’ as owners of their clinical practice. | |

| Kaplan et al, 2023 | Most rural residency programs are too new (1–2 years) to offer substantive insights about their impact on long-term NP retention in rural settings. | |

| Owens, 2018, 2021 | Successful early career transition experiences and professional identity formation were associated with work satisfaction, perceptions of confidence and competence, and no intention to turnover or leave the rural healthcare environment in the first year of practice. |

NP, nurse practitioner. RN, registered nurse.

Preparing for rural healthcare practice

Common to the five articles, we found that preparing for rural healthcare practice was the earliest process in the trajectory of new rural NPs’ early career experience. Patterns of preparation for rural healthcare practice were classified as pre-existing rural registered nurse (RN) experiences, rural NP educational emphases or curriculum, NP student clinical rotation experiences in rural settings, or involvement in a rural postgraduate NP transition-to-practice program42,62-65. NPs considered their past rural experiences foundational to their ability to develop the advanced skills and knowledge required for rural NP practice62,64.

We also found that postgraduate NP residency programs helped prepare NPs for rural healthcare practice. These programs utilize a competitive admission process and typically provide new NP graduates with formally mentored clinical learning experiences and incrementally advancing responsibilities for their first 12 months42. Kaplan and colleagues found that these residency programs were sought by new NPs because of a desire for more rural clinical preparation and professional transition support beyond those provided by their formal educational program42.

Transitioning to rural healthcare practice

The second phase of the NPs’ early career trajectory pertains to their transitioning experiences from being a student to becoming an advanced practice provider in rural health care. Three studies42,62,64 reported that this transition occurs mostly during the first year of practice. The transitioning experience was portrayed as a critical moment in which formalized mentoring, professional support, and structured orientations were needed. Qualitative data suggested that prior rural professional experiences as RNs, educational preparation, and the development of supportive professional and community networks contributed to successful transition-to-practice experiences42,62-64. However, there were insufficient longitudinal empirical data to determine whether rural postgraduate residency programs significantly improve the long-term retention of rural NPs42.

Adapting to and sustaining rural healthcare practice

The final iterative early career phase of rural NPs, after the first transitional year of practice, is adapting to and sustaining rural healthcare practice. There was a substantive gap in the literature about the way this phase is experienced by rural NPs, because practice experiences beyond 15 months were not explicitly represented in the articles42,62-65. Still, there were long-term implications from the findings about NPs’ ability to integrate into a rural community, adapt to the challenges of rural practice, understand rural culture, and form a rural NP professional identity. These experiences were suggestive of adapting to and sustaining rural healthcare practice and were associated with career satisfaction and no intention to turnover62-64. Conversely, NPs’ feelings of isolation and disconnection, which were attributed to a lack of mentorship and insufficient early career support, hindered their ability to adapt to the unique demands of the rural healthcare environment63. Therefore, the final phase of their early career experience as rural NPs involved a dynamic process of both successful strategies and struggles in coping with their transition.

Commitment and persistence of new rural nurse practitioners

The second theme in our analysis related to NPs’ persistence to continue their rural healthcare practice despite the challenges they were experiencing, and their perseverance to grow professionally. The second theme pertains to factors that motivate, activate, and sustain early career rural NP practice. This theme subsumed three aspects of the NPs’ professional experience: motivation to practice in a rural healthcare setting, engagement in rural healthcare practice to enhance confidence and competence, and experience of connectedness and social support in rural healthcare practice42,62-65. These three aspects facilitated their commitment and persistence as new rural NPs (Table 3).

Table 3: Commitment and persistence of new rural nurse practitioners

| Experiences and perceptions | Citations | Synthesis of primary sources |

|---|---|---|

| Motivation to practice in a rural healthcare setting | Kaplan et al, 2023 | NPs with the strongest expressed commitment to work in a rural healthcare setting were those with a prior history of rural personal or professional experience. Motivators to participate in a rural postgraduate NP residency program was influenced by a perceived lack in prior rural RN experiences or NP clinical rotations. Other motivators included financial recruitment incentives to practice in a rural setting, perceived job security, existing personal connections to the rural community, and preferences for rural living. |

| Owens, 2018, 2021 | New NPs reported the following motivating factors for choosing to work in a rural setting: a desire to improve rural populations’ access to primary care, a preference for and expectation of close relationships with patients, families, and colleagues, a preference for the challenging variety of patient needs in rural settings, increased professional autonomy, a passion for lifelong learning in the context of resource-limited settings, and financial incentives or job availability. | |

| Engagement in rural healthcare practice to enhance confidence and competence | Gonzales et al, 2022 | There were no statistically significant differences in recalled perceptions of self-confidence to engage in full-scope practice between rural and non-rural NP participants. Confidence increased significantly after 3 months of practice in both groups. |

| Kaplan et al, 2023 | New rural NPs reported a desire for more confidence in their clinical competence as a motivating factor for participating in a postgraduate residency program. New rural NPs also reported feeling more confident and competent as result of the structured transition-to-practice support. | |

| Owens, 2018, 2021 | NPs reported feelings of overwhelm, stress, and anxiety initially. But, after the first year, all participants reported feelings of satisfaction, competence, and improved confidence with no intention to turnover. | |

| Experience of connectedness and support in rural healthcare practice | Conger and Plager, 2008 |

The presence of other healthcare professionals, accessible communication with urban centers, and sufficient clinical support personnel contributed to perceptions of connectedness. Early career NPs also recognized the importance of involvement in community events, understanding the community culture, and connecting with community social agencies to foster connectedness and support. A lack of supportive professional colleagues and resources led to a sense of disconnectedness and turnover. Insufficient support staff, role diffusion (ie serving in the role of primary care provider as well as case manager), poor communication, and lack of understanding from urban centers regarding rural healthcare constraints also contributed to disconnection. |

| Kaplan et al, 2023 | Rural postgraduate residency programs served as a supportive and progressively autonomous transition-to-practice environment for new NPs, including regular engagement with peers, preceptors, and mentors, structured didactic content, and a gradual increase in productivity expectations. Some programs also offered journal clubs and telehealth instruction. | |

| Gonzales et al, 2022 | Compared with urban NPs, rural NP respondents were significantly more likely to report limited access to referral sources in their practice environment. Rural NPs also reported significantly less or no access to quality improvement projects or committee work, and little to no opportunity for participating in clinic ownership. | |

| Owens, 2018 | Positive relationships with colleagues, staff, patients, and communities enhanced the experience of transition. It was critically important to have a designated mentor along with a successful facility-specific orientation experience in the first year of practice. | |

| Owens, 2021 | Participants practicing as the only provider in their rural location reported feelings of isolation initially. All participants reported role diffusion and lack of anonymity in their practice community. New NPs felt their learning and socialization processes were supported by collaborative interactions with mentors, other providers, interprofessional team members, and patients. |

NP, nurse practitioner. RN, registered nurse.

Motivation to practice in a rural healthcare setting

Intrinsic motivators, originating from an internal value or sense of personal satisfaction, were presented several times in the early career rural NP literature42,62,64. A preference for rural living, prior experiences and existing rural relationships, a passion for rural healthcare practice, and a desire to improve healthcare access for people living in rural communities emerged as recurrent intrinsic motivators to work in rural healthcare settings42,62-64. The desire to increase clinical confidence and competence motivated new NP graduates to participate in rural postgraduate residency programs42. In three studies, extrinsic factors were also reported to motivate NPs; the most common external motivators were financial incentives, including financial opportunities such as loan repayment programs and job security42,62,64.

Engagement in practice to enhance confidence and competence

New NPs desired to improve their professional confidence and competence. Prior rural RN healthcare experience and rural NP educational experiences impacted NPs’ perceptions of confidence to provide safe, quality care for rural patients42,62-64. Participation in formal mentoring opportunities and postgraduate NP residency programs contributed to perceptions of a successful transition-to-practice experience, enhancement of an NP professional identity, and confidence to meet the demands of the rural advanced practice role42,62,64. New NPs’ perceptions of confidence improved over the first year of clinical practice42,62,64,65.

Connectedness and support to sustain rural healthcare practice

The final subtheme relates to the new rural NPs’ experience of support, or lack thereof, in their community of practice. Early in their careers, rural NP participants reported greater difficulty accessing patient referral sources and fewer occasions to participate in quality improvement projects or business opportunities than non-rural NPs65. Furthermore, participants felt disconnected and unsupported by professional consultants and referral resources among urban healthcare providers who misunderstand the unique constraints in personnel, diagnostics, medications, and equipment that inexperienced rural NPs have to navigate63. Insufficient support contributed to feelings of disconnectedness in the rural setting63.

Based on the complexity of the rural healthcare context, new rural NPs recognized a need to establish supportive relationships with the networks available to them, including former classmates, nutritionists, mental health nurses, pharmacists, community health nurses, and electronic resources63. Given the realities of geographic isolation, rural support networks included both local relationships and non-professional community connections, as well as out-of-town relationships with urban healthcare centers. Early career NPs’ sense of local connectedness was enhanced by participating in community events, building trust, understanding the community culture, and connecting with community agencies63. On the other hand, rural ‘disconnectedness’ was characterized by a lack of professional and community networks and relationships, a lack of onsite mentoring, and insufficient clinical personnel and equipment63.

Owens also consistently found that new rural NPs attributed their supportive early career relationships among colleagues, mentors, patients, and rural community members to their successful development of a professional identity and sense of career satisfaction62,64. Conversely, when rural NPs felt disconnected from professional support and development opportunities, and alone in their practice setting, they reported feelings of isolation62,63. New NPs’ perception of isolation and experiences of disconnectedness and loneliness contributed to intentions to leave the community63.

Adaptive and maladaptive early career factors for rural nurse practitioners

The third theme emphasizes factors that helped early career NPs adapt to the challenges of the rural healthcare setting and factors that influenced their intention to leave rural healthcare practice. These adaptive and maladaptive factors seem to have implications for their rural career longevity and are represented in Table 442,62-65. These factors either supported them in the retention of their jobs or influenced their intention to leave rural healthcare practice. We found that adaptive factors were those elements of the early career experience conducive to rural NPs' personal, professional, and social development and wellbeing. Moreover, adaptive factors contributed to their intention to sustain a career in the rural context.

Maladaptive factors referred to rural early career experiences that hindered NPs’ professional identity formation, ongoing professional development, and rural satisfaction (eg insufficient accessibility to the resources necessary for early career adjustment). We also found that maladaptive factors were influential in early career rural NPs’ intention to turnover.

Table 4: Adaptive and maladaptive early career factors for rural nurse practitioners

| Factor type | Early career phase | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Choosing and preparing for rural healthcare practice | Transitioning to rural healthcare practice | Adapting to and sustaining rural healthcare practice | |

| Adaptive | Former personal or professional rural experiences (Kaplan et al, 2023; Owens, 2018, 2019). A desire to provide primary care to rural underserved population (Kaplan et al, 2023; Owens, 2018, 2021). Existing personal or professional support networks in the rural community, financial incentives and rural job opportunities, a preference for rural lifestyle, a preference for full practice scope and professional autonomy (Kaplan et al, 2023; Owens, 2018, 2021). Preparation to advocate for and develop local relationships and a referral network in the rural community of practice (Conger and Plager, 2008). | Participation in a rural NP residency program or access to a designated clinical mentor and formal orientation process (Kaplan et al, 2023; Owens, 2018, 2021). Access to referral sources and social support services for patient care needs (Conger and Plager, 2008; Kaplan et al, 2023; Owens, 2021). Positive communication experiences with providers, nursing staff, patients, interprofessional team members, and urban health centers (Conger and Plager, 2008; Owens, 2018, 2021). Accessible professional development and continuing education opportunities (Kaplan et al, 2023; Owens, 2018, 2021). | Personal connections, social networks, and engagement in local activities to increase familiarity with the people, agencies, and community culture (Conger and Plager, 2008). Relationships with patients, their families, professional colleagues, and the public (Owens, 2018, 2021). An increasing capacity and appreciation for autonomy, collaboration with an interprofessional team, and positive relationships with patients (Owens, 2018, 2021). |

| Maladaptive | Insufficient learning opportunities in NP educational or clinical rotations (Kaplan et al, 2023). Inability to access a rural postgraduate residency programs (Gonzales et al 2022; Kaplan et al, 2023). Ill-preparation for the resource limitations, complexity of care, role diffusion, lack of accessible collegial and electronic support, rural case management challenges, and reported feelings of isolation and loneliness (Conger and Plager, 2008). | Perceptions of isolation due to the relative lack of mentoring, lack of support staff, and lack of referral sources (Conger and Plager, 2008). Few opportunities to engage in professional development and networking activities, including continuing education conferences and professional committee involvement (Conger and Plager, 2008; Gonzales et al, 2022). | Negative or insufficient communication experiences with urban healthcare colleagues who misunderstand the complexity of the rural healthcare context and implications of resource limitations (Conger and Plager, 2008). Challenging personal and professional social boundaries in rural healthcare practice, including role diffusion, lack of anonymity, and limited back-up support for vacation or personal leave (Conger and Plager, 2008) Persistent perceptions of disconnectedness, a lack of relationships within the community, loneliness, isolation, and fewer opportunities for professional development (Conger and Plager, 2008) |

Adaptive early career factors

Adaptive experiences were characterized by supportive social and professional networks within the rural community, engagement in local events, building trust within the healthcare team, and understanding the rural culture beyond the clinical context63. These relationships and experiences were often developed before the start of the rural NP career, resulting from existing personal attachments to the community, rural RN experiences or NP educational clinical rotations, or participating in a rural NP postgraduate residency program42,62-64. As NPs transitioned into rural practice, they noted the importance of supportive communication, reliable access to referral networks and mentorship, formal orientation processes, and involvement in interprofessional teams42,62-64. Although the NPs’ early career experiences beyond 12–15 months of practice were not explicitly referenced in the selected studies, three studies62-64described how these adaptive factors contributed to the NPs’ sense of job satisfaction and lower intention to turnover, including their abilities to establish social networks and perceptions of community connectedness.

Maladaptive early career factors

Maladaptive early career factors were also represented in each of the five articles42,62-65. Maladaptive factors included perceptions of inexperience and isolation, unmet desires for mentoring, unreliable access to professional networks, challenges accessing professional development opportunities, and insufficient backup coverage42,62-65. Participants’ difficulty adjusting to the lack of anonymity in rural communities, and role diffusion in clinical expectations, were also notable62,63. Those new rural NPs who perceived themselves as isolated, disconnected, and unprepared for the realities of rural healthcare practice expressed a higher intention to leave their community of practice63.

Discussion

The aim of this integrative review was to analyze and synthesize research about the phenomenon, identify the gaps in the literature, and discuss implications. Early career NPs represent a substantial and growing proportion of the rural primary care workforce14but need better representation in the rural workforce literature. New rural NPs are frequently ‘lumped’ together in research samples with allied healthcare providers, RNs, experienced NPs, and other population groups27,31,45,66. Therefore, reported findings may not represent the unique practice scope, educational background, support networks, or career stage specific to NPs43. Our review indicates that these specific factors are critical contributors to the early career experiences of rural NPs and necessary to elucidate for an accurate understanding of their professional needs and turnover risks.

Trajectory of early career practice for rural nurse practitioners

The early career phase of rural NPs is a dynamic trajectory towards adapting and sustaining a fulfilling rural healthcare practice, albeit with challenges and struggles42,62-65. Medical and allied health literature supports our findings on the trajectory of early career rural healthcare practice, demonstrating that integrating with rural communities occurs in stages55,67-69. However, our review provides a more nuanced understanding of rural NPs’ transitioning process to confident and competent rural primary care providers.

Preparing for rural healthcare practice

Rural healthcare providers have unique preparational needs, different from non-rural providers1,70-72. Because rural health care is considered to be a distinctly challenging practice environment69,70,73,74, preparation for practice can be enhanced with rural didactic and clinical educational experiences31,39,42,68,70,75-78. Although Gonzales and colleagues (2022) reported no significant differences in perceptions of preparedness between rural and non-rural early career NPs65, other studies involving more experienced rural NPs suggested otherwise78,79. Studies indicate that the unique demands of the rural environment often require rural NPs to expand their skills beyond those learned during educational programs to include a broader range of clinical competencies and procedures to serve their isolated communities41,72,79-81.

Transitioning to rural healthcare practice

The role of formative life experiences and existing relational ties in the rural setting were recurrent findings in the data about transitioning to rural healthcare practice42,62,64. Access to mentoring, formal orientation processes, referral networks, and transition-to-practice supports were also of critical importance42,62,64.

Adapting to and sustaining rural healthcare practice

Current early career rural NP research targets the first year of practice and emphasizes concepts such as preparedness, clinical competence, transition-to-practice experiences, and professional identity development42,62,64,65. Conger and Plager’s (2008) study indicated that psychosocial factors such as community connectedness are also implicated in sustaining a career in rural healthcare practice63. Medical and allied healthcare literature further suggests that sociocultural community integration, including the development of personal and professional relationships with local residents and involvement in community activities, contribute to the successful adaptation and retention of healthcare providers55,69,71,82-84. However, developing these relationships may be especially challenging for individuals with no former personal or professional background in the rural environment55,74,83.

Commitment and persistence of new rural nurse practitioners

While coping with their relative inexperience, new rural NPs must navigate a distinctly complex healthcare context, including difficulty accessing the clinical support they need and the professional engagement opportunities they desire63,65. The motivators, perceptions, and social networks of new rural NPs are important to explore because they provide qualitative data for non-rural educators, researchers, and professional colleagues about the lived realities and challenges of the rural healthcare environment.

Motivation to practice in a rural healthcare setting

Extrinsic motivators for NPs to choose the rural setting for their area of practice included financial incentives, loan repayment options, and job availability42,62,64, which are consistent with findings from a systematic review of rural healthcare providers85. However, it is unclear whether these motivations impact new NPs’ ability to successfully transition to practice and sustain a long-term career in rural health care42. In contrast, intrinsic motivators may carry more staying power. Kaplan and colleagues (2023) reported that NPs’ prior personal and professional experiences in the rural environment, preference for the rural lifestyle, and existing connections to the community were strong internal motivators for choosing rural healthcare practice42. Additionally, altruistic desires to positively impact rural residents’ access to health care emerged as a source of career satisfaction62,64. Advancing an understanding of NPs’ intrinsic motivators for choosing rural practice may improve recruitment policies and target individuals more likely to sustain rural healthcare careers42,46.

Engagement in practice to enhance confidence and competence

For many NPs, the initial months following graduation are turbulent and overwhelming, marked by perceptions of inadequacy, uncertainty, impostorism, and increasing clinical responsibility62,86-88. We found that new rural NPs’ initial sources of confidence to practice in rural healthcare are derived from prior rural work experiences and rural curricular features in NP educational programs42,62,64. However, confidence levels also improved with spending more time in practice, such as in the first 3 months65to a year of practice42,62,64. Again, these findings hold implications for exploring the nuances of preparing early career NPs and the processes that promote experiential learning, relationship-building, and clinical competencies required for rural healthcare practice.

Connectedness and support to sustain rural healthcare practice

Support networks, community integration, and local connectedness emerged as significant contributors to the commitment and persistence of NPs in the rural healthcare setting42,63. Critical processes such as building community connections, establishing a sense of belonging, and navigating rural sociocultural contexts have been reported in the broader workforce literature for years55,69,89-91. These processes need better representation in new rural NP theoretical frameworks, educational outcomes, and retention initiatives. For instance, Gonzales and colleagues (2022) suggested teaching NP students how to make medical and social referrals in rural settings65. Conger and Plager (2008) stressed the importance of educating students about the unique constraints of the rural healthcare environment and their critical need for self-advocacy to develop connections for early career professional support63.

Adaptive and maladaptive early career factors for rural nurse practitioners

Adaptive and maladaptive early career factors are novel concepts in the context of rural NP literature. We found that adaptive factors contribute to career stability, while maladaptive factors impact NPs’ intentions to leave rural healthcare practice. The rural workforce literature has established that the rural patient population suffers from disproportionately complex health needs, inequities in social determinants of health, and widening gaps in their rates and severity of chronic diseases, addictions, mental health crises, and premature death5,6,37,92. However, relatively little is published to account for the unique needs, experiences, and perspectives of the NP population serving them31.

Recommendations for research, education, and policy

The lack of description about early career NP experiences of rural health care beyond the first year of practice leaves an essential gap in our understanding about the processes and experiences that occur between rural NPs’ transition-to-practice career phase and their retention or turnover in rural healthcare practice. NPs who are new to rural life were underrepresented in these data as well. Hence, NPs with no personal or professional rural life history may experience amplified difficulties and unique insights during early career development, including greater challenges establishing their professional and personal support networks and more vulnerability to turnover55.

Prior research focusing on NP graduates’ preparedness for the generic skills and competencies of primary care17,93,94may not capture the unique complexities of rural practice. A targeted approach exploring rural NPs’ perspectives about their preparation for and transition to practice, and long-term retention outcomes in those settings, is indicated41,42,72,78. Rural NPs from a larger catchment area should be represented within a broader window of time during their early careers (ie first through fifth years of practice), so the sequencing of their preparation, processes, values, and responses to the rigors of the rural healthcare context can be deeply explored. An early career theoretical framework, informed by a more heterogeneous rural NP sample, could provide a meaningful foundation for developing future empirical studies and relevant research instruments.

In allied health literature, successfully ‘adapting’ to rural practice has been explored as a key element associated with reduced intention to turnover69,74. However, NP literature lacks clarity about disciplinary-specific components of adapting29, and it needs better definition in the context of rural NP practice. For example, notable adaptive processes such as building community connections, establishing a sense of belonging, and understanding the impact of rural sociocultural factors have been reported in the broader workforce literature for many years but need better representation in early career rural NP theoretical frameworks and research46,69,83,89-91.

The supply of early career rural NP literature is scarce and relatively nascent. Thus, we recommend that policies developed for the recruitment and retention of rural NPs be co-designed using the perspectives of rural NPs themselves46. Educational curricula, student clinical rotations, and postgraduate residency programs should provide experiential opportunities for new NPs to prepare for the intricacies of rural healthcare practice, including the complexity and intensity of care coordination demands, strategies for establishing mentoring support, and how to develop professional referral networks in geographically distanced and resource-limited areas17,42,63,65.

Limitations

The search strategy terms, database limitations, and selection criteria applied to this review may have unintentionally excluded relevant primary research. Because so few studies were identified, caution must be taken about the generalizability of findings. In addition, although no time delimitation was applied to the search and most of these studies were published within the past 5 years, none captured the experiences of new NPs in rural health care in the post-COVID pandemic era. Different themes may emerge if we extend the time range beyond the year 2024. This reinforces the need for ongoing research. Another notable limitation of the articles identified for this review is that all lacked an explicit definition of ‘rural’. This is a common problem in rural healthcare research and there is no universal recommendation or consensus about which definition or criteria to use56,57.

Conclusion

The tension between low resources and high demands in rural areas creates a uniquely complex early career context for rural healthcare providers. Qualitative research on the full continuum of early career processes and rural NP experiences would contribute to advancing rural workforce knowledge about the unique aspects of rural NPs’ preparation, transition, and adaption to the rural healthcare setting5,29,44-46. We found scant scientific literature that specifically represented early career rural NPs, even though they are regarded as an increasingly significant stopgap for the worsening rural primary care physician shortage facing the US2. Specifically, contributors to new NPs’ intention to leave or ability to adapt and sustain a career in rural healthcare practice warrant further exploration. Evidence-informed educational initiatives, postgraduate residency programs, and recruitment policies would benefit from an in-depth understanding of the early career needs of this increasingly prominent sector of the rural primary care workforce17,27,31,42,66,81.

References

You might also be interested in:

2013 - Transforming rural health systems through clinical academic leadership: lessons from South Africa

2010 - Expressions of depression in rural women with chronic illness