Introduction

Oral health promotion strengthens individuals and communities and is essential to reducing the global burden of oral diseases, which affect billions of people and pose significant challenges to public health worldwide1,2. The most prevalent oral diseases or conditions – dental caries, periodontal diseases, tooth loss, and oral cancer3 – remain widely distributed among vulnerable populations in both developed4 and developing countries5, as well as among rural residents in Australia6, Chile7,8, India9, Zambia10, and Brazil11. These conditions are associated with lifestyle factors12 and share risk factors with other systemic diseases13.

The use of holistic approaches is a central strategy for promoting oral health more effectively14. However, the evaluation of this health promotion approach across diverse populations remains insufficiently explored. There is well-documented evidence regarding the effectiveness of interventions such as health-promoting schools15 and the influence of health-supportive environments throughout life16. In Latin America, the most commonly implemented oral health promotion strategies have included educational programs and water fluoridation17. Additionally, interventions focused on acquiring new knowledge or developing practical skills are frequently employed and are considered classic approaches in oral health promotion studies18,19. However, traditional health promotion initiatives implemented under unfavorable contextual factors often yield only short-term effects. A systematic review suggested that the least successful studies failed to adequately address key behavioral determinants of oral health18.

Using the Ottawa Charter as a guiding model, oral health promotion can be implemented through a combination of strategies – healthy public policies, supportive environments, community action, personal skills development, and health service reorientation – to achieve more effective results20,21. Several studies suggest that applying these principles in hospitals and workplaces enhances self-care, health satisfaction, and quality of life22,23. These interventions benefit both individuals and communities by fostering healthier behaviors. However, their application in oral health remains limited, particularly in rural and remote areas, where significant geographic barriers are challenging and could be mitigated by such interventions.

In Brazil, one of the various types of rural settings is represented by riverine communities, who live on or nearby riverbanks. Their way of life depends on the river flows, and so does the use of health services24. Residents in these communities face significant challenges in accessing oral health services, as evidenced by a high percentage of individuals who have never visited a dentist25. They often seek dental care only at advanced stages of disease, primarily driven by pain or the need for tooth extraction26, and exhibit high levels of dental caries27.

The Brazilian health system developed an organizational model adapted to the needs of riverine populations through fluvial units, which provide medical, dental, and other health services. Although this model has increased service utilization28, health inequities persist, partly due to the absence of permanent health teams in these territories to carry out health promotion activities. Given the limitations of the itinerant health service model, riverine populations could benefit from effective health promotion strategies that are conceived, planned, and executed by the residents themselves. Such strategies could help reduce oral diseases and shift the motivation for using health services, which remain predominantly biomedical and curative.

To address these challenges and develop oral health promotion practices that recognize individuals’ autonomy as essential to reducing health inequities, this study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of participatory community interventions on the oral health of a rural riverine population.

Methods

A participatory community-based intervention study was conducted in a rural riverine community in Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil. The study was carried out in the riverine community of Santa Maria, located on the left bank of the Rio Negro, 5 hours by regional boat away from the urban area of Manaus, with access exclusively by river. At the time of the study, the community comprised 47 families, with a low population density, standing out for its strong collective engagement. There were three religious temples, a community center, a preschool and elementary school run by the municipality, and a health local support facility where community health workers (CHWs) were based and provided local support to the fluvial primary healthcare unit. The fluvial primary healthcare unit visited the communities along the river on an itinerant basis, docking monthly in the studied community, offering medical and dental care. In the absence of the rest of the primary healthcare team, basic healthcare services were provided by the CHW and an endemic disease control agent, who were local residents actively engaged in community health care.

Recruitment

The study proposal was initially presented to local leaders, who agreed to participate after deliberation with the community. For the interviews and clinical data collection all adolescent and adult residents of the community aged 15–60 years were invited to participate. They were approached in their homes to provide informed consent for participation in the study.

Interventions

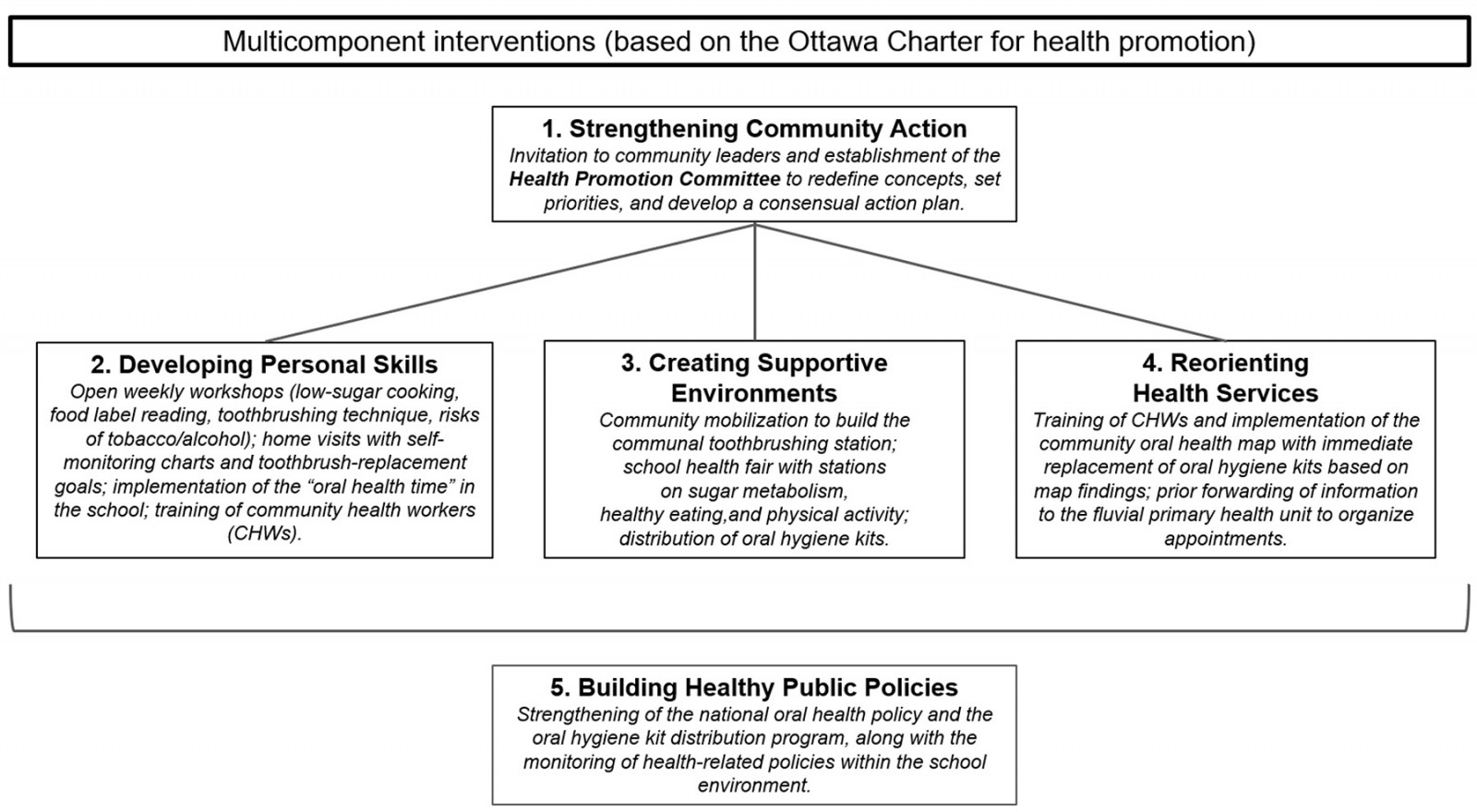

The community implemented a health promotion program focused on oral health, guided by the five action areas for health promotion defined in the Ottawa Charter. The actions are described in the following subsections (Fig1).

Figure 1: Framework of the oral health promotion intervention guided by the Ottawa Charter.

Figure 1: Framework of the oral health promotion intervention guided by the Ottawa Charter.

Action area 1: Strengthening community action

A health promotion committee was established in the community, with a scheduled plan for meetings aimed at fostering community engagement in health promotion through participatory workshops. The committee included the school principal, health local support facility manager, the community leader, one representative from the mothers’ group, and one representative from each religious center. Meetings were held monthly over a 6-month period and were mediated by a dentist with training in public health. The workshop topics included the meaning and social representations of oral health, determinants and risk factors for oral health, and prevention of oral diseases, conducted in 1-hour in-person sessions. During these workshops, decision-making, along with the proposal and implementation of strategies to improve the population’s oral health, was actively encouraged, so that the following actions were all proposed by the committee. Based on these workshops, the different components of the intervention were subsequently implemented concurrently throughout the 8-month intervention period.

Action area 2: Developing personal skills

A dentist (main researcher) and a nutritionist, both with training in public health, conducted workshops and training sessions aimed at developing personal skills for the community, the school, and healthcare workers.

For the community

During individual home visits, a dentist empowered participants to engage in health promotion, create supportive environments, and develop personal skills for a healthy lifestyle. These efforts were tailored to address key individual risk factors, including sugar consumption, oral hygiene, and smoking/oral cancer. Collective activities were conducted through weekly workshops held in a community space, covering topics such as healthy cooking; ultra-processed foods and food labeling; oral hygiene and fluoride; and harmful alcohol use, smoking, and oral cancer. Each face-to-face session lasted for 2 hours and included slide presentations and discussion groups. Additionally, an educational manual on oral health care was distributed using social media, accompanied by videos created by the residents themselves.

For the school

The catering staff received training on sugar and ultra-processed food use, while oral health was integrated into the school curriculum in collaboration with the school principal. Each training session lasted for 1 hour.

For the healthcare workers

Given the significant role of the CHW as the only health team member permanently in the territory, these agents participated in monthly face-to-face training sessions led by a dentist. Topics included oral health diagnosis; common risk factors and manual biofilm control techniques; harmful alcohol use, tobacco, and oral cancer; and case discussions. Educational resources featured slide presentations, case discussions, and feedback on health record monitoring.

Action area 3: Creating supportive environments

Supportive environments for health promotion were identified, planned, and developed collaboratively with community members, based on workshops conducted by the health promotion committee. The local committee decided to construct a communal toothbrushing area for use by students in front of the local school. The community funded the construction independently. After the building was completed, the school implemented mandatory toothbrushing under the supervision of a CHW. Healthy food consumption was also promoted within the school environment by encouraging a reduction in sugar intake. In partnership with the school principal, the committee also decided to organize a school-based health fair for the community. Students prepared themed rooms with educational content on the relationship between sugar and non-communicable diseases, as well as strategies for prevention. Oral hygiene items, including toothbrushes, fluoridated toothpaste, and dental floss, were distributed to the community twice during the intervention, with a 3-month interval between distributions. Visual materials, such as posters on healthy eating, sugar consumption control, oral hygiene, harmful alcohol use, smoking, and physical activity, were displayed in religious spaces, while digital cards were created for distribution via a messaging app.

Action area 4: Reorienting health services

The health unit team, including the manager and CHWs, developed a community map to identify the availability of oral hygiene items in households and reinforcement of tooth-brushing; risk factors for oral cancer; and signs and symptoms related to the oral cavity, such as soft tissue lesions and dental pain. This tool enabled the early detection of issues and facilitated referrals for professional care when necessary. If a lack of oral hygiene items or usage exceeding 4 months was identified, the agent requested a replacement kit from the health center and delivered it to the family. The team updated the community map on a monthly basis.

Action area 5: Building healthy public policies

Health policies within the school environment were monitored, and the workshops promoted the regular identification of obstacles to the adoption of health and intersectoral public policies. Additionally, they emphasized the development of proposals to address these barriers, thereby assisting public managers in their decision-making processes. As part of these efforts, the national oral health policy was strengthened through the scheduled distribution of oral health kits, aligned with the population’s needs, with the distribution and needs assessment carried out by the local health team.

Study variables and data collection

Data collection was conducted at two time points: T0 (baseline) and T1 (8 months after the start of the interventions). Data were obtained through a questionnaire administered via face-to-face interviews and clinical oral examinations. The questionnaire included instruments to assess demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, health-related behaviors, health promotion actions (oral health literacy, oral health beliefs), intermediate health outcomes (dental services utilization), and health and social outcomes (dental pain, dental caries, periodontal status and oral health-related quality of life), as proposed by Nutbeam (1998)29.

Oral health literacy was assessed using the Health Literacy in Dentistry-14 (HeLD-14) instrument, which includes 14 questions measuring the ability to seek, understand, and use oral health information. Items were rated on a 0–4 scale, with total score ranging from 0 to 56. The higher the score, the better the oral health literacy30,31. The oral health beliefs instrument rated the perceived importance of six behaviors – avoiding sweets, using fluoride toothpaste, visiting the dentist, maintaining oral hygiene, drinking fluoridated water, and flossing – on a 1–4 Likert scale. Total score ranged from 6 to 24. The lower the score, the more positive the beliefs32. Health-related behaviors (tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity), as well as dental services utilization and dental pain in the previous 6 months, were measured using questions from the most recent Brazilian National Health Survey and Brazilian National Oral Health Survey33. The OHIP-14 questionnaire, comprising 14 items across seven dimensions (functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability, and disadvantage), assessed oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL). Participants reported impacts over 6 months on a Likert scale (0–4), with higher total scores indicating greater impact on OHRQoL34,35.

The clinical oral examination evaluated periodontal status (gingival bleeding and dental calculus) using a flat no. 5 intraoral mirror (Duflex®) and a WHO-type ballpoint probe (Stainless®). Quadrants for examination were randomly selected by drawing one upper and one lower quadrant. All permanent teeth in the selected quadrants were examined, excluding any primary teeth. Measurements were recorded at six sites per tooth. Gingival bleeding and calculus were noted per tooth if at least one site of the examined tooth presented the condition. The outcomes were represented by the proportion of teeth with bleeding sites and the presence of dental calculus. Additionally, as a secondary outcome, the number of decayed, missing, and filled teeth was evaluated using the DMFT index. Examinations were conducted in a home setting by two trained and calibrated examiners, following the Brazilian National Oral Health Survey 2020 protocol using the in-lux method, with inter-examiner agreement for the DMFT index showing weighted kappa values between 0.843 and 0.907.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis of the data was performed to characterize the participants and evaluated instruments at T0 and T1. The differences in oral health literacy scores, health-related behaviors, OHRQoL, and oral health indicators between the two study times were assessed using the non-parametric Wilcoxon paired test for continuous variables and McNemar and Cochran's Q tests for categorical variables.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (CAAE No. 75442823.4.0000.5020, Federal University of Amazonas). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

Results

A total of 61 individuals from the rural riverine community were assessed in the study at baseline (T0), with a mean age of 35 years (standard deviation ±12.3), ranging from 15 to 59 years. The average number of years of formal education was 10 years (±0.5), with 93.4% stating they could read and write. Just over two-thirds of the sample had a monthly family income of up to one minimum wage. At T1 (8 months later), 60 individuals were reassessed. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the evaluated population at baseline.

The mean total HeLD-14 score was 40.7 (±8.5) at T0 and 45.4 (±5.4) at T1, with increases identified across all domains after the interventions. The largest differences were observed in the accessibility domain (6.4±1.6 at T0; 7.2±0.9 at T1) and the utilization domain (6.5±1.8 at T0; 7.4±1.0 at T1). The economic barriers domain presented the lowest mean score and the smallest variation (3.4±1.9 at T0; 3.9±1.2 at T1). Regarding oral health beliefs, participants had a mean score of 8.0 (±2.1) at T0 and 6.3 (±0.7) at T1. All these differences were statistically significant (p≤0.001). Table 2 presents the mean scores of the instruments.

The proportion of participants who visited a dentist in the previous year increased from 55.7% at T0 to 71.6% at T1, while those who had not visited a dentist for more than 3 years decreased from 3.0% at T0 to 1.6% at T1 (p=0.004). Most attendances were at public services (72.1% at T0; 76.6% at T1), with a very large percentage at the fluvial primary healthcare unit (70.4% at T0; 76.6% at T1). Dental pain in the previous 6 months showed a reduction after the intervention, but the difference was not significant. Data on dental health service utilization and dental pain are presented in Table 3.

Improvements in OHRQoL were also observed following the intervention. The mean Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP)-14 score decreased from 19.3 (±7.3) at T0 to 17.3 (±4.9) at T1, with reductions in all evaluated domains. In terms of periodontal status, the average proportion of teeth with bleeding on probing decreased from 27.1% to 4.8% (p<0.001), while the average proportion of teeth with dental calculus decreased from 10.6% to 5.7% (p=0.001). The DMFT index showed no significant difference between time points. Data on oral health-related quality of life, dental caries, and periodontal status are presented in Table 4.

Table 1: Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics and health-related behaviors in a rural riverine community, Rio Negro, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil

| Characteristic | Variable | n (%) / mean±SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 35±12.3 | |

| Sex | Male | 29 (47.5) |

| Female |

32 (52.4) |

|

| Race/skin color | White | 2 (3.3) |

| Black |

13 (21.3) |

|

| Brown |

46 (75.4) |

|

| Literacy (can read and write) | Yes | 57 (93.4) |

| No |

4 (6.6) |

|

| Years of education |

10±0.4 |

|

| Educational level | Never went to school | 4 (6.6) |

| Incomplete primary education |

9 (14.8) |

|

| Completed primary education |

5 (8.2) |

|

| Incomplete high school |

12 (19.7) |

|

| Completed high school |

28 (45.9) |

|

| Incomplete higher education |

1 (1.6) |

|

| Completed higher education |

2 (3.3) |

|

| Recipient of cash transfer program | Yes | 46 (75.4) |

| No |

15 (24.6) |

|

| Income | Up to half a minimum wage | 13 (21.3) |

| More than half a minimum wage up to one minimum wage |

29 (47.5) |

|

| More than one minimum wage up to two minimum wages |

18 (29.5) |

|

| More than three minimum wages |

1 (1.6) |

|

| Tobacco smoking | Never smoked | 47 (77.0) |

| Currently smokes |

9 (14.8) |

|

| Does not smoke currently but has in the past |

5 (8.2) |

|

| Alcohol consumption | Never | 22 (36.0) |

| Less than once a month |

24 (39.3) |

|

| Once or more per month |

15 (24.6) |

|

| Physical activity | ≥150 minutes per week | 48 (78.7) |

| <150 minutes per week |

13 (21.3) |

SD, standard deviation

Table 2: Oral health literacy and oral health beliefs in a rural riverine community, Rio Negro, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil

| Characteristic | Variable |

T0 (baseline) (mean±SD) |

T1 (after 8 months) (mean±SD) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral health beliefs | 8.0±2.1 | 6.3±0.7 | <0.001 | |

| Oral health literacy | HeLD-14 total score | 40.7±8.5 | 45.4±5.4 | <0.001 |

| Receptivity |

6.7 ±1.3 |

7.0±1.0 | <0.001 | |

| Understanding |

6.2±2.1 |

6.6±2.0 | <0.001 | |

| Support |

6.7±1.7 |

7.3±0.9 | <0.001 | |

| Economic barriers |

3.4±1.6 |

3.9±1.2 | 0.001 | |

| Accessibility |

6.4±1.6 |

7.2±0.9 | <0.001 | |

| Communication |

4.9±2.1 |

5.9±1.5 | <0.001 | |

| Utilization |

6.4±1.8 |

7.4±1.0 | <0.001 |

HeLD-14, Health Literacy in Dentistry-14. SD, standard deviation

Table 3: Utilization of oral health services in a rural riverine community, Rio Negro, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil

| Utilization characteristic | Utilization variable | T0 (baseline) | T1 (after 8 months) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n |

% |

n | % | |||

| Most recent dental attendance | Up to 1 year | 34 | 55.7 | 43 | 71.6 | 0.004 |

| More than 1 year up to 2 years |

17 |

27.8 | 12 | 20.0 | ||

| More than 2 years up to 3 years |

8 |

13.1 | 4 | 6.0 | ||

| More than 3 years |

2 |

3.0 | 1 | 1.6 | ||

| Provider of most recent dental visit | Public service | 44 | 72.1 | 46 | 76.6 | 0.642 |

| Private service |

10 |

16.4 | 5 | 8.3 | ||

| Health insurance |

1 |

1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Other |

6 |

9.8 | 9 | 15.0 | ||

| Place of last dental visit | Fluvial primary healthcare unit | 43 | 70.4 | 46 | 76.6 | 0.780 |

| Urban primary healthcare unit |

2 |

3.2 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Private dental office |

6 |

9.8 | 4 | 6.0 | ||

| Other |

10 |

16.3 | 10 | 16.6 | ||

| Main reason for most recent dental visit | Cleaning, prevention, or check-up | 30 | 49.2 | 33 | 55.0 | 0.532 |

| Dental pain |

1 |

1.6 | 2 | 3.3 | ||

| Tooth extraction |

18 |

29.0 | 13 | 21.6 | ||

| Root canal treatment |

7 |

11.4 | 7 | 11.6 | ||

| Other |

5 |

8.1 | 5 | 8.1 | ||

Table 4: Dental pain, oral health-related quality of life, dental caries, and periodontal status in a rural riverine community, Rio Negro, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil

| Characteristic | Variable |

T0 (baseline) n (%) / mean±SD |

T1 (after 8 months) n (%) / mean±SD |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dental pain in previous 6 months | Yes | 14 (22.9) | 8 (13.3) | 0.057 |

| No |

47 (77.1) |

52 (86.6) | ||

| OHRQoL | OHIP-14 total score | 19.3±7.3 | 17.3±4.9 | <0.001 |

| Functional limitation |

2.9±1.4 |

2.5±1.0 | <0.001 | |

| Physical pain |

3.2±1.6 |

2.7±1.0 | <0.001 | |

| Psychological discomfort |

2.8±1.4 |

2.5±0.9 | 0.002 | |

| Physical disability |

3.0±1.6 |

2.5±1.1 | 0.001 | |

| Psychological disability |

2.7±1.2 |

2.5±0.1 | 0.011 | |

| Social disability |

2.3±0.9 |

2.3±0.7 | 0.400 | |

| Handicap |

2.3±0.9 |

2.2±0.5 | 0.008 | |

| DMFT | DMFT total | 9.4±5.9 | 9.6±6.0 | 0.083 |

| Decayed teeth |

0.8±1.3 |

0.8±1.4 | 1.000 | |

| Missing teeth |

5.8±6.2 |

5.9±6.2 | 0.557 | |

| Filled teeth |

2.8±2.5 |

2.9±2.5 | 0.747 | |

| Periodontal status | Bleeding | 27.1±21.4 | 4.8±9.7 | <0.001 |

| Calculus |

10.6±18.7 |

5.7±13.6 | 0.001 |

DMFT, decayed, missing, or filled teeth. OHIP-14, Oral Health Impact Profile-14. OHRQoL, oral health-related quality of life. SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

The study findings showed that normative and subjective oral health outcomes, as well as oral health literacy, improved after the participatory community-based interventions on the riverine population. Subsequent to the implemented actions, gingival bleeding and dental calculus decreased and OHRQoL improved. Dental services utilization increased, although economic barriers remained a huge challenge. These results support the efficacy of the strategies adopted to promote the oral health of the remote rural population.

Community participation is essential for the success of oral health promotion interventions, particularly in vulnerable populations. Dimitropoulos et al (2018)36 and Dimitropoulos (2020)37 demonstrated that programs co-created with Indigenous and rural communities, including training of CHW, improve adherence to preventive practices and reduce dental caries. These results support our findings, as our community-led intervention also improved preventive behaviors and clinical outcomes. Similarly, interventions led by non-dental professionals, such as nurses and CHWs, also showed a positive impact on oral hygiene and self-care behavior38,39. In addition, school programs that incorporate ongoing education reinforce the importance of integrating various community sectors in promoting oral health15,16,40. To ensure the sustainability of these actions, public policy support is crucial, especially in rural areas where structural barriers limit access to dental care19. Furthermore, active community engagement and the recognition of local knowledge are essential to successful interventions after they enable strategies that are culturally appropriate and better suited to the population’s needs.

Most oral health promotion studies adopt classical strategies, such as fluoridation and supervised brushing, which are broadly implemented in school and community programs to prevent dental caries and improve oral hygiene17,40. The efficacy of fluoride in reducing dental caries is widely recognized and stands as one of the most effective methods for disease prevention at the population level41,42. However, in rural riverine areas, logistical challenges hinder fluoridated water coverage43, and the distribution of fluoridated toothpaste with no cost or using fluoride in other ways remains limited. Moreover, evidence indicates that interventions exclusively based on these strategies have a limited impact when not combined with other health promotion efforts and access to dental care44. Thus, the effectiveness of these initiatives depends on integrated and participatory approaches that foster behavioral and structural changes, ensuring greater equity and sustainability. The positive outcomes found in our study reinforce this need, showing that multicomponent participatory strategies are suitable for rural and remote settings where traditional approaches alone may be insufficient.

The intervention improved oral health literacy, with the greatest gains in the accessibility and utilization domains, while economic barriers showed the smallest change. Oral health beliefs also improved. Similar results were reported by Soares et al (2022)45, who identified the economic barriers domain as the lowest in a population also composed of Brazilian adults and older adults. This similarity reinforces our finding that socioeconomic constraints remain a major challenge, even when educational and behavioral gains are achieved. Oral health literacy and oral health beliefs interventions forged in local context have shown potential for improving oral health in vulnerable populations. Studies involving Indigenous adults in Australia demonstrated that an educational training program led by members of the local Indigenous community, consisting of multiple instructional sessions over 1 year, enhanced oral health knowledge and behavior46,47. In addition, motivational interviewing conducted at home improved oral health literacy in vulnerable Chilean families48.

The relationship between oral health literacy and oral health behaviors and outcomes has been acknowledged, linking low literacy levels to lower tooth-brushing frequency, inconsistent flossing, and increased demand for emergency dental care49-51. Moreover, it was reported that individuals with low oral health literacy also presented a higher prevalence of severe periodontitis52 and faced more barriers to accessing dental services, which contributes to inadequate oral hygiene practices and irregular dental visits53. In terms of oral health beliefs, sociodemographic and psychosocial factors influence oral health. Adults with higher educational levels place greater value on preventive practices54, while parental beliefs and childhood socioeconomic status impact health throughout life55. In rural China, low educational levels were associated with poor knowledge and unfavorable behavior in adults56, whereas negative parental beliefs about fluoride and the importance of teeth increased the prevalence of dental caries in children57.

The interventions improved periodontal conditions, with decreases in bleeding on probing and dental calculus, while the DMFT index showed no significant change. OHRQoL also improved after the intervention, with overall score reductions observed across all evaluated dimensions. Individuals in rural areas tend to experience poorer OHRQoL due to the high prevalence of caries, dental calculus, and subjective oral symptoms, as well as the lack of regular dental care58-60. Our findings suggest that participatory interventions may help counteract this trend, as reductions in subjective impacts were observed despite the structural barriers characteristic of rural areas. In riverine areas, particularly in the most remote communities, worse oral health indicators – including higher levels of pain, caries, and the need for extractions or endodontic treatment – are strongly associated with poorer OHRQoL26,27. In this context, community engagement programs have proven to be effective in improving oral health perceptions and behaviors60. Regarding periodontal condition, socioeconomic inequalities and urban–rural disparities influence both disease incidence and access to treatment, while educational level impacts disease progression61-63. Its prevention requires both individual and population-based approaches, combining health education strategies and wider public policies64, while behavioral strategies that consider the local context contribute to reducing disease progression65.

Dental visits increased, long gaps in care decreased, and most consultations took place in public services, mainly at the fluvial unit, while dental pain showed a decline after the intervention. Access to oral health care in riverine communities of the Amazon is in part provided by fluvial family health teams, which use boats to reach remote areas and visit the localities at a defined time interval66. However, challenges such as geographic isolation, high costs, limited services availability, and a shortage of professionals hinder their utilization25,26. Another study carried out with riverine populations of the Rio Negro showed that a quarter of the riverine population had not received dental care in the previous 3 years25, and that regions served only by fluvial units show higher rates of tooth loss compared to those covered by fixed health units67. Adopting preventive models that incorporate the social and cultural realities of the population, rather than exclusively reinforcing the biomedical paradigm, may encourage the continual use of services and reduce the demand for care only in emergency situations. Community-led interventions, carried out by those who live in the area, can further enhance engagement and ensure culturally appropriate strategies.

The main limitation of an intervention study without a control group is the difficulty in attributing the observed effects exclusively to the intervention, as the absence of an unexposed group prevents direct comparisons. Additionally, natural changes over time may influence the results independently of the intervention, restricting the study's external validity and making it harder to generalize the findings to other populations and clinical settings. However, selecting an appropriate comparison group can be challenging, especially in heterogeneous communities with distinct characteristics. The adoption of a single-group pre-test–post-test analysis may be justified by greater community engagement in the intervention, which influences the results and makes comparisons with an external group more complex. Moreover, this approach allows for greater control over variables affecting outcomes, such as socioeconomic factors and access to healthcare services, reducing the risk of bias resulting from differences between groups.

This study highlights the positive impact of community-driven interventions on oral health literacy, service utilization, and periodontal health in a riverine population, despite persistent economic and structural barriers. The findings support existing evidence on the effectiveness of culturally tailored participatory approaches in advancing oral health equity, particularly in geographically isolated communities.

Conclusion

The proposed community-based interventions positively influenced oral health in a rural riverine population. The significant increase in HeLD-14 scores, particularly in accessibility and utilization domains, suggests improved capacity to seek and use dental care services, although economic barriers remained a challenge. The higher frequency of dental visits indicates increased engagement with the healthcare system. Additionally, improvement in periodontal conditions highlights the intervention’s effectiveness in addressing both subjective and clinical oral health outcomes. Despite the lack of change in the DMFT index, the overall improvements reinforce the potential of integrated participatory strategies in enhancing oral health within vulnerable communities. Future studies should explore the long-term sustainability of these interventions and assess their applicability in other remote populations to guide evidence-based public health policies.

Funding

The study was funded by the Amazonas State Research Support Foundation (FAPEAM), Program Inova Amazônia Fiocruz, call for projects 04/2022, by the ILMD Fiocruz Amazônia PROEP-LABS, call for projects 025/2022. The project was carried out during the term of the Postgraduate Development Program in the Legal Amazon (PDPG -CAPES), call for projects 013/2020. FJH is a FAPEAM Research Productivity Fellow.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this study.