Introduction

South Asia is home to approximately a quarter of the world’s population and continues to experience one of the highest fertility rates worldwide with around 35 million births each year1. The region encompasses the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka2. South Asia encounters substantial challenges in maternal and neonatal health, with high rates of morbidity and mortality3. Annually, around 48,000 maternal deaths occur in South Asia4, largely due to preventable causes such as postpartum haemorrhage, sepsis and hypertensive conditions5. Similarly, neonatal mortality is concerning, with approximately one million newborn deaths each year, often linked to complications during birth, infections, and prematurity and low birth weight5. These figures must be improved for the region to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 3, which aims to reduce global maternal mortality to less than 70 per 100,000 live births and neonatal mortality to 12 per 1000 live births6.

To address these poor outcomes, countries in South Asia have accelerated midwifery development in recent decades by expanding education, strengthening professional regulation and increasing workforce deployment, acknowledging the critical role of qualified midwives in reducing health disparities7-9. Historically, birth in South Asia was predominantly managed by traditional birth attendants10, but high maternal and neonatal mortality rates have led to a shift towards training professional midwives7. Governments and organisations began to develop midwifery programs, particularly in countries like Bangladesh7, India11 and Pakistan9, where the numbers of midwives are gradually increasing.

This is important because greater availability of midwives in low- and middle-income countries is strongly associated with reduced maternal and neonatal mortality, particularly where midwifery services are well integrated12. The quantity of midwives is crucial and their experiences are equally important, as midwives can only provide optimal care when working within their full scope of practice, adequately resourced and without facing significant barriers.

While progress has been made in developing, growing and strengthening midwifery in South Asia, the rural and remote regions continue to face distinct and persistent challenges that hinder equitable access to quality maternity care13. Factors such as restricted access to healthcare facilities14, insufficient infrastructure15, and social and economic inequalities16 in rural South Asia have a substantial role in exacerbating these adverse health outcomes. In many rural areas, however, traditional birth attendants continue to provide most maternal and neonatal care17,18, reflecting the persistent gaps in the rural distribution of qualified midwives19. This unequal access means that women in remote communities often face limited antenatal and postnatal care options, increasing the risk of birth complications18. Additionally, there is emerging evidence that climate change and natural disasters have harmful effects on maternal and neonatal health in rural regions, as they exacerbate existing vulnerabilities and limit access to essential healthcare services during critical times20.

Midwives in rural areas, whether in high-income or low- and middle-income countries, face multiple challenges that can greatly impact their ability to provide effective maternal and neonatal care21,22. Systemic barriers include inadequate access to resources and limited professional support, which hinder their capacity to provide high-quality care21-24. Societal norms and the patriarchal hierarchy within the healthcare system can further complicate the role of midwives, frequently positioning them in roles of diminished authority25.

From a scholarly perspective, the existing evidence examining the experiences of midwives in these rural regions is fragmented and has not yet been systematically synthesised. Given the common challenges faced in developing midwifery across South Asia, it would be beneficial to explore the experiences of midwives in these rural areas collectively, enhancing the impact and significance of the findings. Hence, this review aims to explore, map and analyse the available literature on the documented experiences of midwives in rural and remote areas of South Asia. By examining their lived experiences, the review will highlight the current strengths, challenges and gaps in midwifery practice. This information could inform future policy, guideline development and localised practice-focused interventions. The evidence collected may assist in designing context-specific strategies to better support midwives and improve maternal and neonatal health outcomes in rural South Asia.

Methods

Study design

A scoping review was conducted to map the existing evidence on midwifery experiences, identify gaps in the literature and highlight future potential research priorities and policy development26. The Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews was used due to its rigorous, structured approach to evidence synthesis, ensuring transparency, thoroughness and reliability in identifying and analysing existing research27.

Eligibility criteria

The Population, Concept, and Context28 framework was used to systematically identify and delineate the key topics for exploration, ensuring a focused and comprehensive approach to the literature search. As detailed in Table 1, the population criteria focus on midwives, including variations of titles reported across the region, while excluding traditional birth attendants and the term ‘skilled birth attendant’ unless it explicitly refers to midwives. The concept encompassed any aspect of midwifery practice or experiences, and the context related to rural and remote areas within South Asian countries. This review includes both qualitative and quantitative studies, randomised controlled trials and systematic and integrative reviews, along with opinion papers.

Table 1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria using the Population, Concept, and Context framework28.

| Aspect of framework | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

Midwives Nurse-midwives Auxiliary nurse-midwives Community midwives Public health midwives |

Traditional birth attendants including traditional midwives Skilled birth attendants |

| Concept | Midwifery practices and experiences | |

| Context |

South Asia including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka Rural and remote locations |

Countries outside South Asia Urban locations |

Search strategy

The search strategy aimed to identify relevant peer-reviewed studies and grey literature using a three-step approach. First, an initial search of PubMed was conducted to identify relevant articles, with keywords from titles, abstracts and index terms used to inform the development of a comprehensive search strategy. In the second stage, a systematic search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus and CINAHL in April 2025. The search combined keywords and Boolean operators, using truncation to capture variations such as "midwi*" to capture ‘midwife,’ ‘midwives’ and ‘midwifery’. The search terms were based on the Population, Concept, and Context framework and included a combination of ‘midwifery’, ‘rural’, ‘remote’ and the countries of South Asia as shown in Appendix I. Studies published from 2000 onwards were included, in line with the approximate establishment period of professional midwifery in the region. Although no language exclusions were applied, the search was conducted in English. The final stage including searching grey literature using Google and Google Scholar, and manually searching reference lists, which ensured a comprehensive coverage of the topic.

Data extraction and analysis

A modified data extraction tool29 was used to systematically capture relevant information including study type, participant and key findings, with this allowing for the identification of common key themes, patterns and gaps in the literature. Thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (2006)30 was employed to synthesise and interpret the findings from the included studies. An inductive approach was used, allowing themes to be generated from the data without imposing a predetermined framework. All included studies were read in full and relevant data were extracted into a coding framework. Initial codes were generated line-by-line to capture key concepts and patterns in the findings. These codes were then collated into potential themes, which were reviewed, refined and clearly defined through iterative comparison across studies. The process involved constant checking of the data to ensure that themes accurately reflected the evidence, and final themes were agreed upon by the research team. This approach enabled a nuanced interpretation of the documented experiences of midwives in rural and remote settings of South Asia.

Quality assessment

Although quality assessment is not typically required in a scoping review31, it was incorporated here as an additional measure to evaluate study quality. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool was used for this purpose, designed to assess methodological rigor across qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods research32. This tool provides a quality score based on specific criteria and is recognised for its validity, reliability and accuracy33. Studies were scored according to five criteria, with each fulfilled criteria contributing to a cumulative score out of 100%32. A score of 100% indicates high methodological quality, while lesser scores suggest a lower quality32.

Results

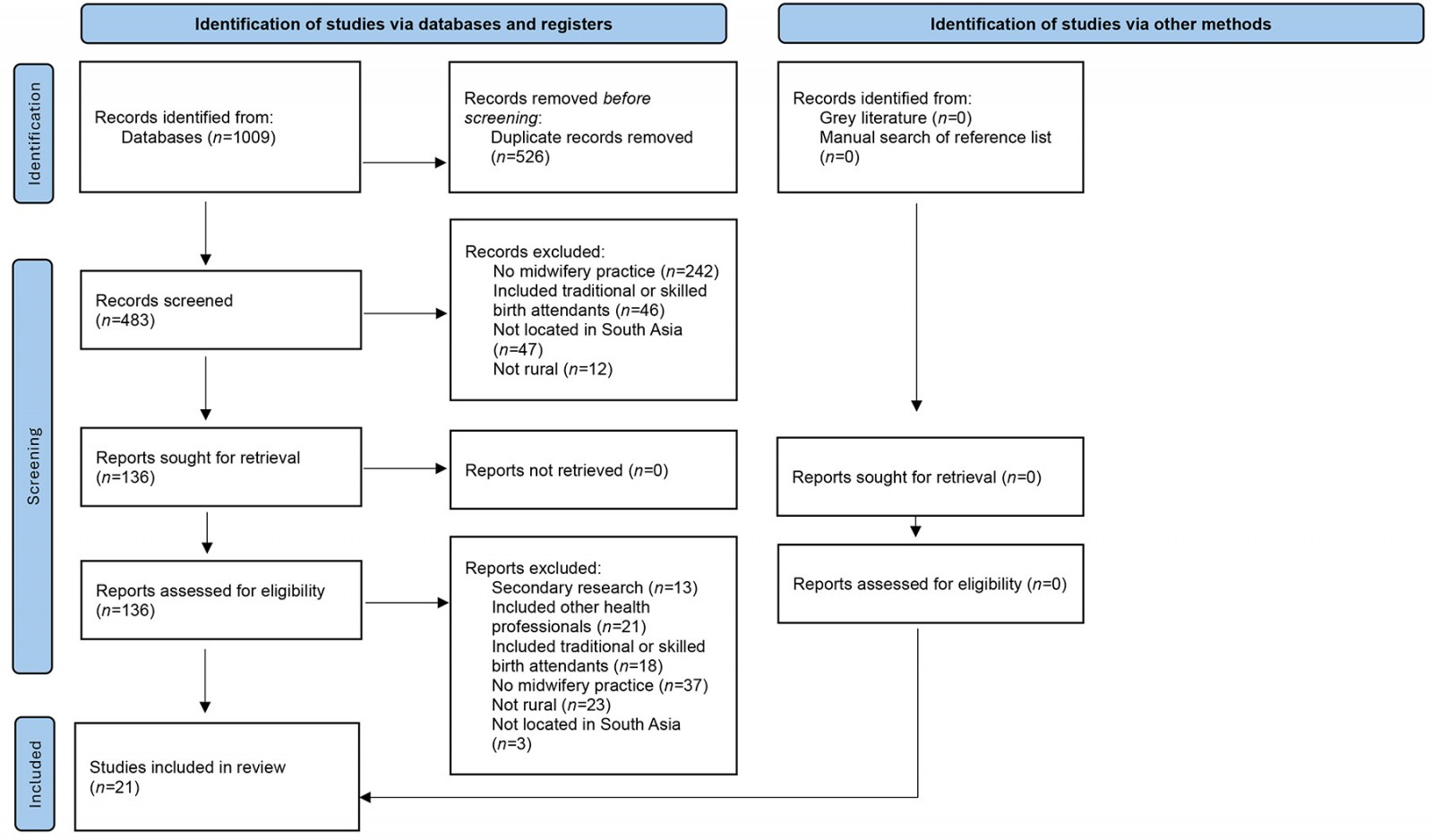

The initial search yielded a total of 1009 articles. After removing duplicates, 483 articles remained for screening. Following a screening, 347 articles that did not align with the established inclusion and exclusion criteria were excluded, leaving 136 articles that were retrieved, read and evaluated for eligibility based on these criteria. The reasons for exclusion included secondary research (n=13), inclusion of other health professionals (n=21) or traditional birth attendants (n=18), no midwifery practice included (n=37) and not located in rural regions (n=23) or South Asia (n=3). Ultimately, 21 articles were included in this study. This search strategy was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses34 guidelines (Fig1).

Figure 1: Identification and inclusion of literature using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart34.

Figure 1: Identification and inclusion of literature using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart34.

Publication characteristics

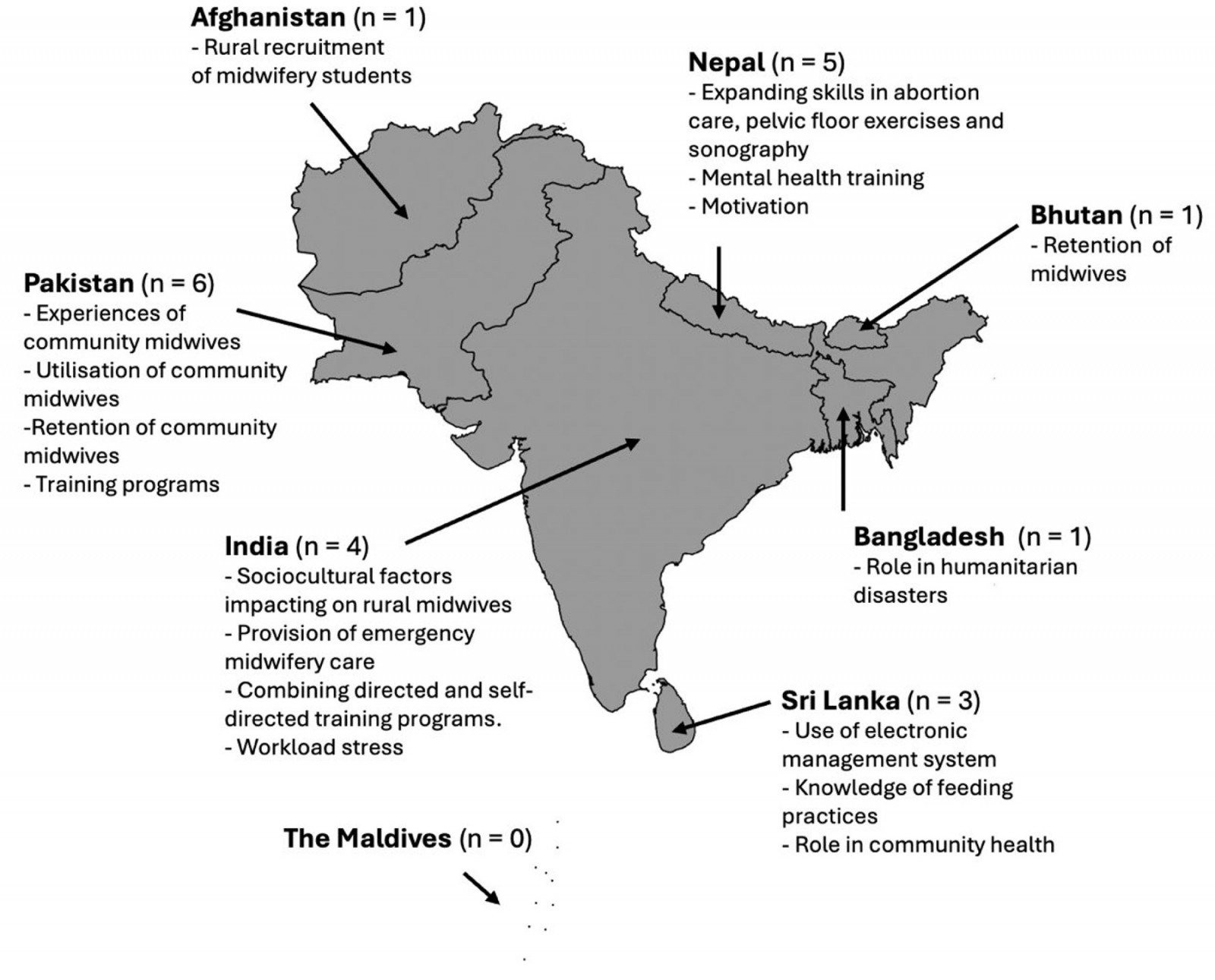

Overall, the studies covered a diverse range of topics related to midwifery, with a publication time frame of 2009 to 2025, and most studies published since 2016 (Appendix II). The publication characteristics revealed contributions from various countries in the regions, including Afghanistan (n=1), Bangladesh (n=1), Bhutan (n=1), India (n=4), Pakistan (n=6), Nepal (n=5) and Sri Lanka (n=3), while no research was found regarding the Maldives (Fig2). A range of research methodologies was employed, comprising qualitative studies (n=8), quantitative analyses (n=9), mixed-methods studies (n=3) and case studies (n=1). Interestingly, the terms for midwives varied across countries, such as nurse-midwives in India, auxiliary nurse-midwives in India and Nepal, community midwives in Pakistan, public health midwives in Sri Lanka, and midwives in Bangladesh, Bhutan and Afghanistan. Because all these terms related to professional training that culminated in a midwifery qualification, they were considered appropriate for inclusion.

The qualitative studies used in-depth interviews and focus group discussions to explore a wide range of topics, including the influence of social factors on the acceptance of midwives35, the experiences of midwives36, the barriers and facilitators affecting midwifery care37, and service utilisation38. Additionally, these studies examined the impact of mental health training on midwifery practices39, the feeding and infant nutrition practices and knowledge of midwives and mothers40, the midwives’ experiences with promotion of community health interventions41 and experiences of completing the Helping Babies Breathe training program42.

Nine studies included utilised quantitative methods, including questionnaires, surveys, observations, descriptive case review and program evaluation, and a health service utilisation report. The topics explored included factors affecting the retention of midwives43,44, workload stress45, emergency obstetric care46,47, pelvic floor muscle training education for midwives48, midwifery-led ultrasonography49 and abortion care50, and implementation of electronic information management system51.

Three studies used mixed-methods approaches, including interviews, focus group discussions, surveys and semi-structured feedback forms to examine the retention of midwives in rural employment related to various recruitment strategies52, developing a tool for measuring midwifery motivation53 as well as exploring the effectiveness of directed and self-directed training54. A case study was conducted to investigate the role of midwives in delivering care during humanitarian crises and emergency situations55.

The articles reviewed revealed several key themes, including commitment to being a midwife, scope of practice education, resources and workforce, technology, society and culture as well as environment and weather. These themes serve as a framework for discussing the findings.

Identified themes

Commitment to being a midwife

Midwives across rural South Asia demonstrate a profound commitment to their clinical roles, with many expressing a deep sense of pride and responsibility for improving the health of their communities37,53. In rural Nepal, auxiliary nurse-midwives reported being highly motivated by their work, viewing it as a vital contribution to maternal and neonatal health53. Similarly, community midwives in rural Pakistan identified themselves as trained health professionals, providing comprehensive maternal care in stark contrast to traditional birth attendants36. Midwives’ increasing confidence in managing obstetric and neonatal emergencies is notable in the literature, with nurse-midwives in rural India effectively assessing and referring women in midwife-led clinics for emergency care, achieving significant success – with only one recorded maternal death over 8 years46.

Nurse-midwives have shown competence in dealing with complex emergencies, such as postpartum haemorrhages, and have further developed their skills over time, even in managing complex cases like twin births46. In rural Pakistan, community midwives reported that completing the Helping Babies Breathe program was highly beneficial in enhancing their neonatal resuscitation knowledge, practical skills and overall confidence42. Despite these achievements in complex and emergency care, a critical gap persists in knowledge regarding basic infant and child feeding and nutrition practices, as evidenced in rural Sri Lanka, where the understanding of public health midwives falls short of national clinical guidelines40.

Scope of practice

The data revealed insights into auxiliary nurse-midwives working within the normal scope and an expanded scope of midwifery practice, including areas such as abortion care50 and sonography49, as well as pelvic floor muscle training48. A study from Nepal involved the training of auxiliary nurse-midwives in rural and remote regions for 5 days in medical abortion procedures, resulting in a 98.5% success rate50. Women also received pain management as part of their care, with an 85% uptake of post-abortion contraception, including oral contraceptives, implants and intrauterine devices50. Another study in rural Nepal involved the training of auxiliary nurse-midwives to use sonography for detecting third-trimester complications49. The auxiliary nurse-midwives demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in identifying non-cephalic presentations, multiple gestations and placenta praevia49. A cost analysis of this intervention showed this approach was projected to prevent 160 perinatal deaths at a cost of US$65 (A$100) per life saved over a 5-year period49. Additionally, training auxiliary nurse-midwives in pelvic floor muscle exercises enhanced their knowledge and resulted in improved pelvic floor muscle strength in mothers who participated in the program48.

Professional education and training

The evidence concerning the education and training of midwives, community midwives and auxiliary nurse-midwives in rural regions was notably limited, yet key insights emerged regarding gaps in communication training35, reliance on senior staff for guidance37,53 and confidence in their professional skills37. In rural India, auxiliary nurse-midwives expressed concerns about inadequate training in essential communication and negotiation skills, which are critical for navigating the often unwelcoming village environments in which they work35. They also reported a lack of awareness about their legal rights and how to manage harassment or abuse encountered in the field35. Conversely, auxiliary nurse-midwives from Nepal53 and community midwives from Pakistan37 noted that senior staff frequently played a crucial role in providing education and support, helping to enhance their clinical knowledge. This same study from rural Pakistan37 highlighted that community midwives felt well prepared after their 18-month training and 6-month internship, perceiving themselves as competent and capable qualified professionals, despite the challenges they faced. Auxiliary nurse-midwives in rural Nepal reported that further training in perinatal mental health greatly enhanced their competencies, particularly in pathophysiology, counselling, making appropriate referrals and reducing the stigma associated with mental health conditions in their communities39. Both directed and self-directed training programs for auxiliary nurse-midwives in rural India effectively enhanced their knowledge, skills and confidence in areas like pre-eclampsia and neonatal resuscitation54. Additionally, more than half of the participants retained crucial knowledge and skills as found through an assessment at 3 months post-training54.

Resources and workforce availability

Significant challenges concerning midwifery resources and workforce availability persist across various rural regions in South Asia. In rural Pakistan, for instance, inadequate remuneration for midwifery services is a pressing issue37,47, with community midwives receiving a monthly stipend of US$50 (A$74)37. These midwives reported being expected to supplement their income by charging clients for their services, despite indicating that most women were unable or unwilling to pay37. Auxiliary nurse-midwives in rural India highlighted a critical shortage of essential supplies, medications and appropriate facilities, often contending with minimal equipment, substandard accommodation and poor transportation options35. A separate study conducted in a rural region of India reported that 72% of auxiliary nurse-midwives experienced work-related fatigue, 51% suffered from muscle strain linked to their duties and 54% reported experiencing workplace stress45. In rural Pakistan, inadequate transportation services and insufficient security measures were frequently cited as barriers to effective midwifery care47. Regarding the workforce, a study conducted in rural Afghanistan revealed that community-led recruitment strategies, facilitated by community mobilisation efforts, resulted in higher employment rates in rural regions compared to traditional recruitment methods reliant on national or regional entrance examinations52. Research in rural Bhutan indicated that the retention of midwives in remote areas was positively correlated with factors such as higher average monthly income, personal origins and values as well as favourable working and living conditions43. Likewise, in rural Pakistan, community midwives were significantly more likely to stay in midwifery after graduation if a family member also worked in the health sector44.

Technology

There was limited evidence on the utilisation of technology in midwifery care, with only three studies addressing this issue45,49,51. The first study introduced an electronic information management system for public health midwives in rural Sri Lanka, yielding overwhelmingly positive outcomes51. The public health midwives expressed high satisfaction with the system, showing a strong preference for its continued use and potential expansion across the region. The primary reason for this favourable response was the substantial time savings compared to traditional handwritten documentation methods51.

As previously mentioned, a study conducted in rural Nepal provided auxiliary nurse-midwives with ultrasound training for third-trimester assessments, enabling them to identify potentially life-threatening complications and significantly improving maternal and neonatal outcomes49. A study conducted in rural India found that 45% of auxiliary nurse-midwives faced challenges using mobile and tablet applications while performing their tasks45.

Society and culture

Sociocultural factors emerged as the most prominent theme affecting midwifery care, encompassing issues like patriarchy35, gender norms35,39 and community politics35-37,53. The patriarchal structure of society, along with entrenched gender norms and social restrictions, was particularly evident in a study from rural India, where auxiliary nurse-midwives faced these challenges in community settings rather than hospitals35. Gender norms complicated discussions on topics like contraception, especially with men, who perceived these midwives to possess questionable morals35. Moreover, the societal preference for male children led to midwives receiving reduced or no payment when assisting the birth of baby girls, or to their exclusion from future births altogether35. Similarly, in rural Nepal, auxiliary nurse-midwives identified the birth of a girl as a factor contributing to maternal depression39. Unfortunately, instances of sexual harassment were frequently reported by auxiliary nurse-midwives in rural India35.

The literature available suggests that acceptance of midwives within communities varied across countries, significantly influencing their ability to provide effective care. In rural India, auxiliary nurse-midwives from outside the community often encountered resistance, making it challenging to provide care35. This hostility was partly due to the auxiliary nurse-midwives being non-locals, but was also deeply rooted in the caste system, a rigid and complex social hierarchy where social status dictates their societal and professional roles35. Auxiliary nurse-midwives perceived as belonging to a lower caste faced severe discrimination, including restrictions on physical contact with women and frequent abuse35.

In contrast, community midwives in rural Pakistan were mostly embraced as vital members of the community, having established strong, trust-based relationships with women36,37. Many women described midwives as blessings, noting their availability at any hour and their willingness to walk long distances to provide care37. Similarly, in rural Sri Lanka, public health midwives successfully integrated into their communities, offering maternal and child healthcare services while also providing essential links to state health services, promoting sexual and reproductive health and advocating for comprehensive maternal care41.

Environment and weather

An interesting insight from the literature was the significant impact of extreme weather and environmental conditions on midwifery care. In rural Pakistan, where community midwives provide home-based care, adverse weather was identified as a major barrier to care provision36. For example, snow in high-altitude and mountainous regions severely hindered community visits, inducing anxiety among midwives36. Similarly, during the rainy season, frequent road blockages and landslides further complicated their ability to reach women in need37. In contrast, midwives deployed to flood-affected rural regions in Bangladesh were found to be highly effective in providing midwifery care, particularly during perinatal emergencies and referral to tertiary health care facilities55.

Figure 2: Summary of study results based on country in South Asia.

Figure 2: Summary of study results based on country in South Asia.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this scoping review represents the first comprehensive exploration of literature regarding the diverse experiences, knowledge and practices of midwives in rural and remote settings of South Asia. It identified challenges encountered by midwives, auxiliary nurse-midwives, community midwives and public health midwives in providing maternal and neonatal care, which are often intensified by entrenched sociocultural beliefs35,37, resource limitations35,37,47, inadequate funding35, geographic isolation and extreme weather conditions36,55. The available literature suggests that, despite these significant obstacles, empowering midwives by expanding their full scope of practice49,50, implementing modern technology51 and fostering community integration37 are effective strategies for enhancing midwifery care. Furthermore, combining research from various countries highlights that differing sociocultural settings, midwifery practices and geographical contexts could significantly influence midwifery care in rural South Asia, suggesting the necessity for tailored and individual interventions.

While pregnancy and birth are recognised as a deeply significant rite of passage around the world56, social and cultural factors play a crucial role in shaping midwifery care in rural South Asia57. The dominance of traditional norms in these regions creates considerable obstacles for midwives, whose contemporary clinical practices frequently conflict with entrenched ideologies and longstanding customs58,59. This challenge is not limited to South Asia but mirrors a broader trend observed in developing nations, where attempts to modernise healthcare systems often neglect cultural sensitivities, resulting in diminished community acceptance and adequate utilisation of available services60. A large study highlighted that interventions aimed at addressing cultural barriers are essential for enhancing maternal and newborn health outcomes61. More attention needs to be paid to understanding and integrating local cultural norms into healthcare delivery, which can substantially influence service uptake61. Such a culturally sensitive approach could be effectively implemented in South Asia, enabling midwives to fully utilise their diverse skill sets within a practice framework that respects and incorporates local customs and practices%u200B

A notable finding from this review was the significant role and benefits of incorporating modern technology into midwifery care across rural areas. Implementation of electronic health management systems51 and ultrasound technology49 has proven advantageous for both auxiliary nurse-midwives and the communities they serve. Rural regions in South Asia present immense potential for the adoption of cost-effective and sustainable technologies. For example, the use of telehealth services by midwives led to increased interactions with pregnant women and improved satisfaction by women62. In Bangladesh, midwives trained in telehealth within urban settings observed a marked increase in clinic attendance and enhanced antenatal education for women and their families63. Given the widespread availability of mobile phones and service, feasibility and positive health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries64, this technology could be leveraged further to improve the quality of maternal and neonatal care.

The International Confederation of Midwives stressed the importance of ensuring midwives possess the required knowledge and skills to function within their full scope of practice65, with the findings demonstrating the substantial benefits of this approach in areas like abortion care50. These findings resonate with global data indicating that when midwives are empowered to deliver comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services, significant advancements in maternal and neonatal health follow66. A predictive modelling study even suggested that fully utilising the skills of midwives and deploying them globally could avert up to 67% of maternal deaths, 64% of neonatal deaths and 65% of stillbirths annually by 203566. Nonetheless, implementing such comprehensive care faces hurdles, particularly in patriarchal societies, where sensitive services such as contraception and abortion can encounter resistance67. Encouragingly, South Asia is progressively advancing sexual and reproductive health rights, creating opportunities for midwives to provide these crucial services effectively and safely68.

Rural South Asia, with its diverse geography – including the mountainous regions of Bhutan and Nepal, the coastal and river deltas of Bangladesh and the remote atolls of the Maldives – is particularly vulnerable to adverse weather events69. The present review identified that midwives in these regions already face significant challenges posed by these conditions, for example community midwives in rural Pakistan identifying extreme weather, such as snow and flooding, as a major barrier to providing essential care36. Given that South Asia is at high risk for natural disasters exacerbated by climate change, these challenges are expected to intensify, resulting in transportation disruptions, food and water shortages, and adverse impacts on healthcare systems69. Additionally, climate change appears to be influencing maternal health outcomes, as evidence from Bangladesh points to increased rates of hypertensive disorders among pregnant women, attributed to rising salinity levels in rural areas70. This emphasises the critical need for climate action and the development of strategies that ensure midwifery services can be maintained amid worsening environmental conditions.

Limitations

While attempts have been made to ensure a high-quality methodology, this review has several limitations. Although the search was broad and allowed for articles beyond the English language, the search terms themselves were restricted to English, potentially excluding relevant studies published in languages from the region.

Additionally, the variability in terminology used to describe midwifery roles across different South Asian countries may have caused some relevant studies to be overlooked. A key limitation of this review lies in the risk of overgeneralisation, which may obscure important contextual differences within individual countries. Moreover, this review did not examine the preference and perceptions of women regarding midwifery care, which is an important aspect that warrants further exploration. Understanding these views could provide valuable insights into the utilisation of midwifery services, potentially identifying areas for improvement. Importantly, while this review represents the first systematic account of midwifery experiences across South Asia, it is essential not to generalise the findings, as each country and region presents has distinct cultural and societal contexts that impact and shape the role and practice of midwives. Despite these limitations, the themes extracted can inform future research and practice-orientated initiatives. This topic is extremely important for the region and for achieving a key United Nations Sustainable Development Goal.

Conclusion

This scoping review highlighted the diverse experiences of midwives across South Asia, discussing both the significant challenges and promising practices that impact their roles in contributing to maternal and neonatal health outcomes. The findings identified the critical need for targeted interventions to address barriers such as sociocultural constraints, inadequate resources and community integration. Future research should focus on expanding the scope of practice of midwives to enable comprehensive sexual and reproductive healthcare in rural South Asia. Additionally, interventions must address sociocultural barriers, such as patriarchal norms and assess the impact of climate change on midwifery services to ensure sustainable healthcare provision. Importantly, midwifery care across South Asia is significantly shaped by diverse contextual factors, with promising advancements addressing the needs of women and their newborns, although continued culturally appropriate efforts are required to ensure equitable health outcomes across the region.

Funding

This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Stipend Scholarship.

Conflicts of interest

The authors confirm that they have no financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work presented in this article.