Introduction

Teletherapy is an effective form of mental health service delivery for many populations1 and can extend mental health services to rural and remote communities that otherwise have limited access to care2-4. The proliferation of teletherapy in these areas presents unique challenges that complicate efforts to improve teletherapy as a mode of service. Prominent among these challenges are technological barriers such as access to high-speed internet and technology infrastructure, issues with insurance coverage and reimbursement, concerns about privacy and security, and limits to interjurisdictional practice3-6. There are also cultural considerations for rural teletherapy practice, such as understanding a distant community’s history and customs, which may present complex challenges for clinicians2,7,8. However, how and under what circumstances clinicians address rural and cultural variables in teletherapy practice, especially when they do not live in the same communities as their patients, is not well understood.

Alaska mental health and service needs

Alaska is a frontline setting to explore clinicians’ significant experiences providing teletherapy to rural communities, given its high proportion of rural and remote communities and acute need for mental health services. Alaska is by far the largest US state by land mass9, nearly three-quarters of its communities are not connected to the road system10, and nearly one-third of Alaskans live in rural areas11. Clinicians are often located in the state’s urban centers or regional ‘hub’ communities, and rural and remote communities tend to rely on community-based health infrastructure. Alaskans have higher rates of substance use, suicide, and serious mental illness for youth and adults compared to US national averages. Suicide is the leading cause of death among adolescents and young adults in Alaska, with 63.3 deaths per 100,000 people – a rate that has risen in recent years, is higher than the national average, and is highest among Alaska Native individuals12,13. Despite the acute need for services, the Health Resources and Services Administration identified 341 mental health professional shortage areas across Alaska. Approximately 56% of the state’s population live in health professional shortage areas14. These are only some of the many contextual variables that professionals within Alaska’s mental health system must consider.

Clinicians working in rural Alaska serve a diverse demographic. With about 16% of Alaska’s population identifying as Alaska Native or American Indian, Alaska has the highest percentage of Indigenous residents of any US state9 – spanning 11 distinct cultures across geographically, economically, and linguistically diverse regions15,16. Nearly 60% of individuals across Alaska’s rural areas identify as Alaska Native17. Non-Indigenous people of color also constitute large proportions of the population in many rural communities18. Furthermore, rural and remote communities across Alaska face distinct economic inequities compared to urban areas – shaped by structural, political, and geographic realities, many of which are consequences of colonization. For example, although lucrative natural resource industries (eg fossil fuels, fishing, mining) are established in rural and remote regions, they operate in limited enclaves, with most high-paying jobs and wealth bypassing local communities. High rates of unemployment and poverty are compounded by costs of living that far exceed those in urban centers16. These realities underscore how geographic and socioeconomic conditions shape access to resources and health care in rural Alaska, and how rural-serving clinicians in Alaska often work with a range of populations that extend beyond any singular rural demographic.

Teletherapy models and guidelines

Scholars and healthcare agencies have created models for implementing teletherapy services in rural communities. For example, the US Department of Veterans Affairs established a model to increase access to mental health care for rural Native veterans19,20, emphasizing collaboration with ‘cultural bridges’ and care coordinators who promote engagement and culturally responsive care through community outreach, multisystem navigation, technological support, professional collaboration, and development of local referral networks20. However, the time and resources needed to build these relationships and systems may not be possible for practitioners outside major healthcare systems.

Summary and research question

Clinicians must recognize and respond to the ways that rurality and remote service provision impact their rural patients’ experiences with teletherapy. However, little is known about the most salient clinical events (ie the critical incidents) that occur during rural teletherapy, and how those events inform clinicians’ practices. There is a need to further explore the practice of rural teletherapy beyond its technological and administrative challenges and general practice guidelines. Therefore, this study sought to explore what critical events informed clinicians’ approach to teletherapy with rural patients in Alaska, and how these events influenced their practice.

Methods

This study used the critical incident technique (CIT)21 as well as thematic analysis22 to explore the most salient events that informed clinicians’ approach to teletherapy with rural patients in Alaska. As a qualitative methodology, CIT has been used by psychotherapy researchers to identify turning points that can inform training23-26, as well as with questionnaire-based research27,28. Within the CIT framework, qualitative data collected in this study were analyzed using thematic analysis22, which complements CIT by providing a nuanced approach to understanding participants’ critical event data.

Participants

Participants were licensed clinicians who had provided teletherapy to rural patients in Alaska and did not live in the patients’ community themselves (ie ‘remote’ teletherapy). Participants were recruited via messages on a statewide professional email list and social media groups, as well as via requests to leaders at various Alaskan behavioral health organizations. We aimed to recruit enough participants so that the critical events reported sufficient coverage of the activity being studied29. As an exploratory study with tight participation parameters, a response of 20–30 participants was expected and sufficient for this study. This sample size is consistent with other CIT studies about clinical turning points and counselor development27,28,30.

Twenty-six participants completed the survey. Full participant demographics are presented in Table 1. Most participants endorsed that they currently resided or lived in Southcentral Alaska (84.6%), the location of Alaska’s largest city, Anchorage, with a few residing in Interior (11.5%) and Southeast (3.8%) regions. This is roughly consistent with overall population distributions in Alaska. Participants reported serving patients across all regions: Southcentral (80.8%), Southeast (69.2%), Interior (57.7%), Southwest (65.4%), and Far North (53.8%).

Table 1: Demographics of participants in study of critical events that inform Alaskan clinicians’ approaches to teletherapy with rural patients (N=26)

| Characteristic | Variable | n | % or mean±SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 26 | 45.9±11.3 | |

| Gender | Female | 22 | 84.6 |

| Male | 4 | 15.4 | |

| Identify as rural resident | Yes | 6 | 23.1 |

| Somewhat | 4 | 15.4 | |

| No | 16 | 62.3 | |

| Years licensed | 11.9±9.1 | ||

| License held | Licensed professional counselor | 16 | 61.5 |

| Licensed clinical social worker | 6 | 23.1 | |

| Licensed marriage and family therapist | 1 | 3.8 | |

| Licensed psychologist | 3 | 11.5 | |

| Years practicing teletherapy | 5.9±4.1 | ||

| Years practicing rural teletherapy | 5.6±4.9 | ||

| Received training in teletherapy | 25 | 96.2 | |

| Received training in rural mental health | 22 | 80.8 | |

| Amount of practice that is teletherapy | None/very little | 3 | 11.5 |

| Less than half | 5 | 19.2 | |

| About half | 6 | 23.1 | |

| More than half/all | 12 | 46.2 | |

| Self-identified race/ethnicity | African American or Black | 1 | 3.8 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 | 3.8 | |

| Middle Eastern or North African | 1 | 3.8 | |

| White | 23 | 88.5 | |

| Multiracial | 3 | 11.5 | |

| Hispanic origin | No | 26 | 100 |

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

SD, standard deviation.

Data collection

Data collection involved an anonymous demographic questionnaire and writing prompt that asked participants to ‘think about experiences you have had providing teletherapy to rural patients in Alaska who lived in a community other than your own’ and then ‘recall a specific clinical event with a rural patient that most informs your current approach to rural teletherapy in Alaska’. Participants wrote responses to the following prompts: ‘Write a brief narrative about this event or instance: describe what led up to the event, what happened, and the outcome’; ‘Describe how this event informs your current approach to rural teletherapy in Alaska’; and (optional) ‘What would have better prepared you for this event?’ Given that this study focused on clinicians’ experiences with rural patients without tight parameters of what constitutes rurality, participants were able to describe experiences with any patient who lived outside of Alaska’s major population centers: Anchorage (population 287,145), Fairbanks (population 95,356), and Juneau (population 31,685)9.

Data analysis

Following the CIT method, the first step involved defining the analytical frame of reference: to better understand the experiences of clinicians who provide rural and remote teletherapy within Alaska and to develop practice guidelines for rural teletherapy. In the second step, the first author (PLN), a White male raised in Interior Alaska, reviewed and identified all critical events across and within participants’ narratives, sorted them into content categories, and defined each category. No data were determined irrelevant to or outside of the frame of analysis. Initial coding by the first author was then reviewed and recoded by an independent rater (CMB, the second author), an Alaska Native woman and longtime educator in rural Southeast Alaska communities. Reflexive discussion and code refinement occurred after each round. A second independent rater (EIA, the third author), a Hispanic male raised in urban Texas, repeated the process, which was again followed by reflexive discussion and consensus among all authors. This approach aligned with and enhanced the next steps of CIT – deciding on the level of specificity among the content categories and definitions, as well as sorting incidents into defined categories to establish replicability.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the University of Alaska Anchorage Institutional Review Board (IRB) (IRB approval number 2178244-4). Each participant read and agreed to an informed consent form before anonymous participation. The form asked participants to affirm their status as a licensed mental health clinician in Alaska and that their responses would not include any personal identifying information or protected health information.

Results

The 26 participants in this study provided 27 critical event narratives. Per the survey design, each participant described, in writing, a critical event relating to rural teletherapy practice, their perceived outcome of the event, and an optional narrative describing what would have better prepared them for the event. Many narratives included multiple codable elements within a theme or overlapping themes represented by distinct codes. Other narratives included multiple distinct codes representing distinct themes. Tables 2, 3, and 4 summarize the critical events, outcomes, and preparedness themes along with descriptions, frequencies (percentage of total codes associated with that theme), and narrative excerpts.

Critical events

Analysis of critical event narratives yielded 49 codable elements comprising 17 individual codes, organized into six overarching themes (presented in Table 2).

Table 2: Critical event themes identified in study

| Theme | Description | Rate (%) | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural and community context | Events where the patient’s presentation, therapeutic process, and/or mode of care is influenced by cultural and/or contextual factors in their environment. | 36.2 | ‘She ultimately came to her next appointment and was in a room that appeared completely dark, and she was huddled in blankets. She informed me that she missed her previous appointment because her uncle's home, where she was staying, did not have heat and she was up all night tending to the wood stove to keep herself and her younger cousins warm.’ |

| Logistical and technological challenges | Events where teletherapy is challenged due to internet connectivity issues or other barriers within the patient’s environment that affect continuity of care, attendance, or service delivery. | 23.4 | ‘Due to issues with fiber optic lines, patient has been unable to attend multiple sessions in a row. One session was canceled day prior, the next session they tried to call in, but phones were available only for emergency calls and neither video or audio worked through telehealth platform.’ |

| Crisis management and safety concerns | Events where the patient or a patient’s family member presents with a medical, mental health, or other safety concern requiring immediate intervention. | 19.1 | ‘A family member attempted to assault her and her toddler while I was on the phone with them.’ |

| Complex clinical presentations and patient support | Events where the clinician works with a patient presenting with complex needs or presents with a unique circumstance requiring adaptability to maintain continuity of care. | 17.0 | ‘A client who worked on the [name of community] was needing to continue services ... we ended up utilizing phone sessions to ensure continuity of care.’ |

| Clinical boundaries and professional errors | Events where the clinician must set boundaries with their patients or when there is an inadvertent confidentiality breach. | 4.3 | ‘Meeting with a client who had previously disclosed [domestic violence] and only after a few minutes realized that the client's partner was just off camera but able to hear conversation.’ |

| Miscellaneous | Other odd events that impact teletherapy or when the clinician reports there not being any critical events that stand out in their practice. | 4.3 | ‘A client doing the session from her back yard in [name of community] and then a black bear came into her yard and scared her away.’ |

Theme 1: Cultural and community context

Critical events related to the theme of cultural and community context were most frequent. Within this theme, elements coded as ‘encountering generational, natural, and environmental traumas in rural contexts’ and ‘encountering diverse rural sociocultural contexts and community norms’ emerged most. For example, one participant described a boating accident that killed a woman who was highly connected in the patient’s community, whereas another participant described a patient who ‘literally had to climb a mountain to get [data] service so we can talk’.

Theme 2: Logistical and technological challenges

Within the theme of logistical and technological challenges, ‘internet connectivity’ was the most frequent code. Multiple participants described how the lack of reliable internet in rural communities impacted their patients’ abilities to attend treatment, or at other times required switching from video to audio-only sessions.

Theme 3: Crisis management and safety concerns

Within the theme of crisis management and safety concerns, which was cited with similar frequency as the logistics and technology theme, ‘addressing suicide risk’ was the most frequent code. This code often applied to instances where clinicians had to safety plan for when emergency services were not readily available or accessible due to the remote location of their patient.

Theme 4: Complex clinical presentations and patient support

Within the theme of complex clinical presentations and patient support, ‘complex clinical presentations’ was the most frequent code. This code largely represented narratives involving patients with multifaceted issues requiring advanced intervention skills. For example, one participant described working with a patient who ‘had gone for days without sleep and then started being paranoid about his family’, ultimately requiring an emergency welfare check coordinated remotely.

Theme 5: Clinical boundaries and professional errors

Within the theme of clinical boundaries and professional errors, ‘setting clinical boundaries’ and ‘inadvertent confidentiality breaches’ codes were cited with equal frequency. These codes applied to largely unexpected situations where clinicians had to respond to patients presenting in a compromised state or in environments that posed ethical or safety concerns. For example, one participant described setting boundaries with a patient who was drinking alcohol in session, and another situation where their patient’s abusive partner was just offscreen and could hear their conversation.

Theme 6: Miscellaneous events

The ‘miscellaneous’ theme applies to odd or extraneous events that were cited infrequently, or when the participant could not think of a critical event in their rural teletherapy work. For example, one participant described a bear scaring a patient in her yard during a session.

Critical event outcomes

Seventy codable event elements emerged from participants’ ‘outcome’ narratives, representing 18 individual codes organized into seven themes, which are presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Critical event outcome themes identified in study

| Theme | Description | Rate (%) | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural and contextual sensitivity | Events that resulted in the clinician increasing their sensitivity to cultural and/or contextual factors unique to their patient’s rural community, influencing their understanding of their patients' lives, treatment, and other forces that impact their work together. | 30.0 | ‘This experience was a stark reminder for me that folks living in rural areas often do not have access to ‘givens’ that we have in larger cities, including heat and running water. The burden of providing for oneself and one's family in the ways that many Indigenous folks within our state do in rural and remote areas cannot be overlooked when it relates to a client's goals, needs, treatment plan, etc.’ |

| Teletherapy access and access challenges | Events that resulted in highlighting additional teletherapy access challenges or facilitators, as well as actions clinicians have taken that address or reinforce service access, that are unique to rural and remote Alaska. | 17.1 | ‘I am unable to help without the ability to meet. She is unable to get the help she needs at a time when being cut off from the rest of the world makes things harder.’ |

| Crisis management and planning | Event results in clinician taking extra steps to plan for, assess, and respond to situations that present risk for their patients. | 14.3 | ‘I make sure I know where they are at the start of every session and have emergency and non- emergency numbers programmed in my phone or have someone I can text to get the welfare check going if it goes bad. We also really talk about what's a crisis and I do more assessment for suicidal ideation and safety planning.’ |

| Flexibility in treatment | Events that result in clinicians adapting their mode of treatment delivery and/or clinic policies to facilitate treatment and continuity of care. | 14.3 | ‘This experience affirmed my tendency to provide folks with multiple exceptions to the rule ... because I am aware of the complicated factors and barriers that may prevent someone from being able to join a telehealth session consistently in these areas.’ |

| Other clinical challenges | Events that resulted in clinicians being more intentional about setting boundaries as well as becoming more aware of frustrations with the work. | 11.4 | ‘I discuss boundaries ... have on clothes, please put down your device if you have to go to the bathroom, no driving, no alcohol or drug use in the session.’ |

| Positive outcomes | Events that result in clinician noticing generally improved therapeutic outcomes as a result of their efforts to establish, maintain, or further their rural and remote teletherapy work with patients. | 8.6 | ‘I could tell that the client was excited to share their knowledge and experience ... [and] how much whaling meant to [them] ... this session strengthened our therapeutic alliance, and contributed to a positive therapeutic outcome.’ |

| Professional development and support | Event results in clinician seeking additional supervision, consultation, or learning in order to meet the unique service needs of their patients. | 2.9 | ‘I engaged in consultation and supervision for good measure, and I had previously taken 2–3 trainings about the ethics of and specific techniques for providing therapy remotely.’ |

| Other | Events that result in another outcome not otherwise described in other themes. | 1.4 | ‘... also, there is a loss of income for me.’ |

Theme 1: Cultural and contextual sensitivity

Outcomes relating to cultural and contextual sensitivity were most frequent. Within this theme, multiple elements emerged that were coded as ‘increasing sensitivity to rural contextual factors’, defined as the clinician becoming more responsive toward rural situational and environmental factors, such as limited access to resources, sheer remoteness, or lack of other ‘givens’ in non-rural contexts that impact patients’ lives and health care. Emerging with similar frequency in this theme were events coded as ‘increasing sensitivity to rural cultural factors’, defined as the clinician becoming more aware of factors such as the values, heritage, and practices significant to their patient’s life and community. While often overlapping and interconnected, these ‘context’ and ‘culture’ codes are differentiated by their emphasis on situations and environments unique to patient rurality (context) versus how their patients enact practices, beliefs, and values (cultural) specific or non-specific to their rurality.

Theme 2: Teletherapy access and challenges

Within the theme of teletherapy access and challenges, ‘anticipating and preparing for technological challenges’ was the most frequent code. Participants described preparing for any anticipated service disconnection by ensuring a backup form of communication, during and outside of crises.

Theme 3: Crisis management and safety planning

Within the theme of crisis management and safety planning, ‘preparing for and addressing safety concerns’ – whether it be local resource planning, confidentiality checks, location verification, suicide assessment, or proactively establishing disconnection plans – were cited similarly to codes within the teletherapy access and challenges theme. In these cases, participants’ responses were specific to crises.

Theme 4: Flexibility in treatment

Within the theme of flexibility in treatment, most codable elements depicted clinicians becoming more fluent and comfortable with switching from video to audio-only modalities, whereas a few other participants described being more open to allowing policy and procedure exceptions due to the various ways sessions are disrupted by rural contextual factors.

Theme 5: Other clinical challenges

Within the theme of other clinical challenges, many participants described elements coded as ‘setting and maintaining boundaries with patients in session’. Boundaries that participants described were often about ensuring reliable phone connections for backup communication, as well as forming robust crisis management plans as prerequisites for initiating services. In other instances, boundaries involved behavioral expectations, such as wearing proper clothing and abstaining from substance use in session.

Theme 6: Positive outcomes

The theme of positive outcomes represented instances where participants perceived the critical event being resolved satisfactorily. Within this theme, many participants noted events that became coded as ‘strengthening confidence in teletherapy practice’. Multiple participants described how their critical event reinforced their current teletherapy practices.

Theme 7: Professional development and support

In the theme of professional development and support, participants described seeking additional supervision, consultation, or learning.

Theme 8: Other outcomes

The ‘other’ theme described event outcomes not otherwise reflected in any of the other themes, such as a clinician noticing a loss in income.

Critical event preparedness

Analysis of the 16 narratives (optional survey item) about what would have made clinicians more prepared revealed 36 codable elements comprising 14 individual codes, categorized into three overarching themes. The ‘preparedness’ themes that emerged from the data are presented in Table 4.

Table 4: Critical event preparedness themes identified in study

| Theme | Description | Rate (%) | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness and experience | Clinician identified a need for greater professional and/or personal experience with rural and remote teletherapy and/or with rural and remote populations in general. | 50 | ‘Having traveled to a rural village to better understand their lived experience or having that lived experience myself.’ |

| Training and education | Clinician identified a need for additional training or educational opportunities specific to rural and remote teletherapy. | 41.7 | ‘More discussion of the ethics, techniques, and other specific issues related to remote therapy delivery being discussed in therapist spaces. Greater availability of trainings and/or better publication of trainings so I can hear about them. National standards related to teletherapy and similar services.’ |

| Resources and infrastructure | Clinician identified a need for more professional resources specific to rural and remote teletherapy or better infrastructure to support the work. | 8.3 | ‘It was difficult to maintain a good internet connection and the screen frequently froze along with other tech issues.’ |

Theme 1: Awareness and experience

Within the theme of awareness and experience, illustrated by half of responses, participants emphasized the importance of gaining experience in rural contexts, including living in or spending time in remote Alaskan communities.

Theme 2: Training and education

The theme of training and education included calls for more training on reconnecting and establishing safety outside of sessions, rural ethics, emergency response in areas without services, developing national rural teletherapy standards, and offering supervision focused on rural and remote contexts beyond basic cultural information.

Theme 3: Resources and infrastructure

Within the theme of resources and infrastructure, participants highlighted the need for improved internet connectivity, and advance preparation and sharing of emergency plans and resources.

Discussion

This study explored the critical events that most informed clinicians’ approaches to remote teletherapy with rural patients in Alaska. It also explored the event outcomes as well as participants’ beliefs about what might have better prepared them to address such events. The data revealed multifaceted accounts of what participants perceived to be the most complex, challenging, or notable elements of practicing rural and remote teletherapy in Alaska. Across the critical event and event outcome narratives were prominent themes of attending to rural contextual and cultural factors; responding to crises, traumas, and complex clinical concerns; navigating technological barriers and ethical challenges; and practicing clinical and administrative flexibility in light of unique circumstances with their patients. Regarding what would have better prepared them for these events, participants identified greater awareness and experience, more training and education, and better resources and infrastructure as most important. Altogether, these themes highlight the complexity of rural and remote teletherapy and add to the teletherapy literature by demonstrating the necessity of conventional teletherapy practice standards and rural mental health competencies, while also illustrating their insufficiency to fully address the many interacting forces that impact this clinical work. Findings suggest that teletherapy and rural mental health competencies should be viewed through a broader framework that includes contextual humility, a concept that is introduced and explored here.

Contextual humility encompasses clinicians’ awareness of and respect for the unique situational and environmental factors that shape rural patients’ lives. The concept of contextual humility emerged from the qualitative data because no other construct adequately described how participants responded to and learned from events where a clinical, cultural, ethical, technological, and/or administrative concern interacted with a rural environmental pressure, creating novel situations requiring thoughtful and complex responses. Teletherapy facilitated a service that may have been inaccessible to patients otherwise; it also complicated interventions and challenged clinicians to address variables within unfamiliar contexts. For example, some participants described grappling with traumas or crises within their patients’ rural settings that might not have arisen, or that may arise at lower rates, in urban areas. Others described situations in which their patients’ rurality profoundly impacted their ability to consistently attend sessions, follow through with recommendations, or receive help during a mental health or medical crisis. The participants, who were living in other (often more urban) communities, had to adapt their expectations, assumptions, and interventions to align with their patients’ psychological, physical, and situational realities. Therefore, interventions required both contextual and cultural humility, as well as many other clinical competencies. This was captured best by one participant who reflected that the ‘givens’ of one community could not be assumed for another.

Contextual humility overlaps with cultural humility, which Hook et al (2013) defined as ‘having an interpersonal stance that is other-oriented rather than self-focused, characterized by respect and lack of superiority toward an individual’s cultural background and experience’ (p. 353)31. However, contextual humility extends beyond cultural humility by addressing how environmental and situational forces interact with cultural, clinical, ethical, technological, and administrative elements of teletherapy. Scholars like Goodwin et al (2023) have discussed factors such as rural housing conditions, poor internet connection, and limited resources that influence rural and remote teletherapy, albeit through the lens of cultural competency7. However, a cultural lens alone risks conflating the enactment of cultural practices, beliefs, and values with environmental and situational pressures – especially in crises like those described by many participants, which required adept interventions tailored to patient context. In other words, social and structural determinants of health are not the same as culture32. Many participants described needing to enhance their crisis preparation and response protocols, practice administrative flexibility, and set firmer boundaries with patients. These reflections frequently stemmed from situations where a rural environmental pressure interacted with a clinical, cultural, ethical, technological, and/or administrative concern. Therefore, contextual humility creates more conceptual space to understand, anticipate, and respond to challenges within rural and remote settings through a virtual mode of care. As illustrated by one participant:

She ultimately came to her next appointment and was in a room that appeared completely dark, and she was huddled in blankets. She informed me that she missed her previous appointment because her uncle's home, where she was staying, did not have heat and she was up all night tending to the wood stove to keep herself and her younger cousins warm. By the time her appointment came, she was so exhausted that she slept through it.

The narratives in this study also reflect how rural and remote teletherapy encounters are inherently cross-contextual, much like Sue and Sue (2022) asserted that all clinical encounters are cross-cultural33. Multiple participants described increased vigilance in anticipating, assessing, preparing for, and adapting to crisis and other novel situations not necessarily familiar in their home environments, such as how a death can broadly affect the community or how rural geographic and socioeconomic factors may change healthcare utilization behaviors. Some clinicians responded with flexibility and ‘outside the box’ approaches, such as adapting clinic policies or fluidly switching between video and audio formats. Others emphasized more deliberate boundary-setting and clearer prerequisites to initiating services, such as providing crisis resources to patients before intake or ensuring well-defined disconnection plans. Still others described these experiences as prompts to become more trauma-informed and practice humility in light of differing pressures and priorities from what may be seen in an urban area. These adaptations reflect advanced integration of well-established teletherapy competencies (eg described in Maheu et al, 2018) while incorporating them into rural and remote teletherapy settings34. These adaptations suggest that competence in rural and remote teletherapy involves more than incorporating teletherapy-specific skills on top of in-person clinical practices. Rather, it involves integrating teletherapy competencies within a contextual and cultural humility framework that accounts for environmental and situational factors unique to rural care, where the clinician and patient are participating from potentially very different settings.

Recommendations for training, practice, and research

The results from this study point to several implications for teletherapy training, practice, and future research. Taken together, these recommendations emphasize the importance of contextual humility as a guiding concept for all remote teletherapy, and rural teletherapy in particular.

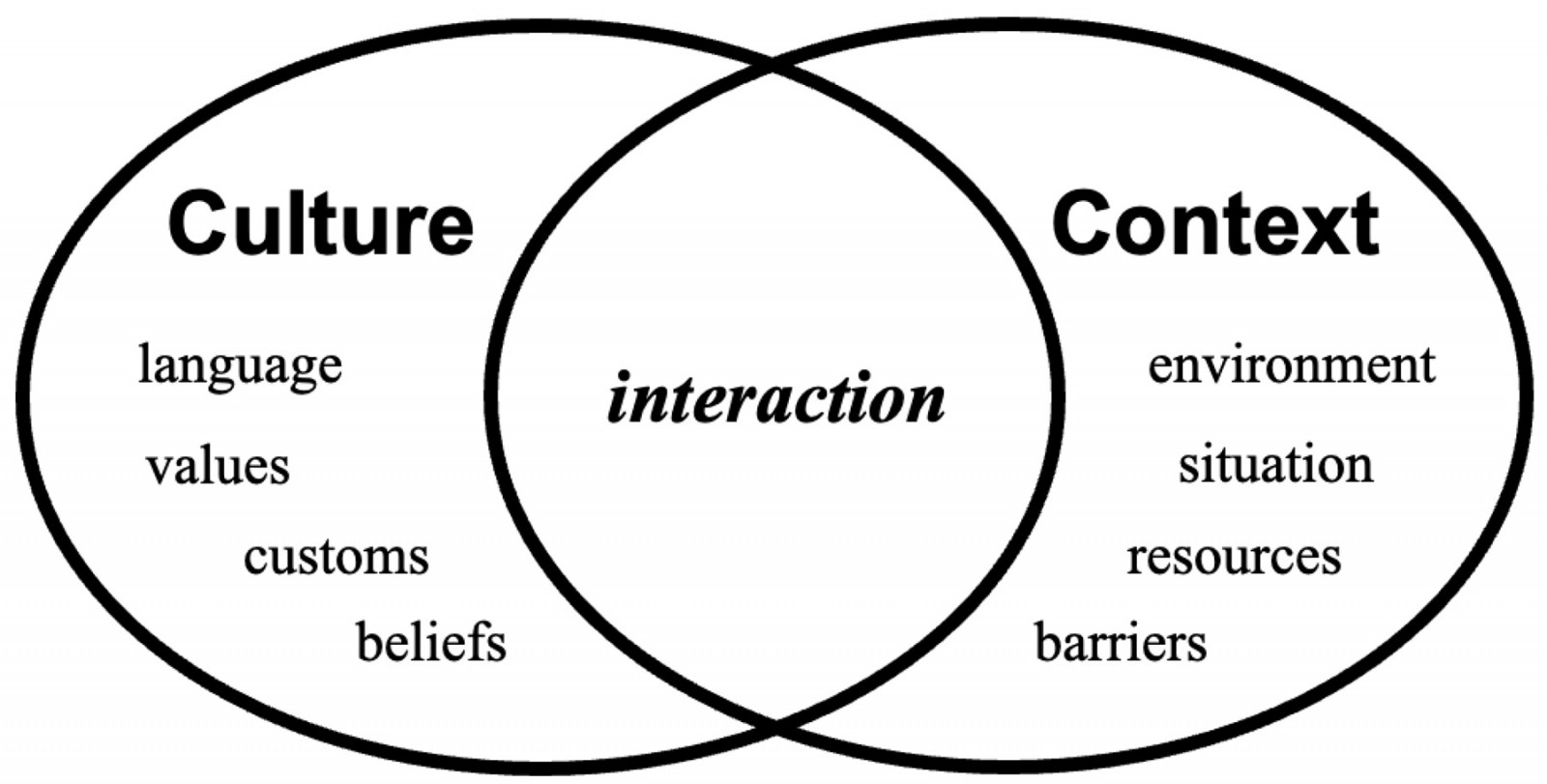

This study highlights the need to expand the scope of rural teletherapy competence to include contextual assessment, responsivity, and reflexivity. For instance, Maheu et al. (2018) identified ‘cultural competence and diversity’ as an essential subdomain of teletherapy, asserting that clinicians should ‘[assess] for cultural factors influencing care’ and ‘[create] a climate that encourages reflection and discussion of cultural issues in an ongoing manner.’ (p. 97)34. Regarding rural mental health, Malone (2011) stated that ‘adaptation of professional practice norms is often required to accommodate geographical barriers and resource limitation’ (p. 293)35. The present study integrates and expands these ideas, suggesting that competence in rural and remote teletherapy explicitly includes assessing for diverse contextual (ie environmental and situational) factors influencing care, fostering ongoing reflection and discussion of such factors with patients, and adapting practice norms to accommodate geographical barriers, resource limitations, and historical and social contextual factors. A unified framework (Fig1) using both cross-contextual and cross-cultural lenses can enhance existing teletherapy guidelines, placing specific skills within a dynamic framework responsive to rural and remote settings rather than in discrete domains.

Adding and integrating a contextual lens to rural teletherapy training should also explicitly include awareness, knowledge, and skills pertaining to the situational and environmental realities impacting rural and remote teletherapy. Several participants in this study highlighted the extra preparatory measures they now take to account for these variables before working virtually with rural patients following a crisis, emphasizing the explicit effort needed to most effectively practice with rural and remote patients. It would also mean that all practice guidelines would be framed in light of the conflicts that can arise when situational and environmental pressures impact the implementation of conventional skills or practice guidelines. This would not only emphasize preparedness on behalf of clinicians but also acknowledge the need for clinicians and organizations to embrace flexibility and humility when practicing teletherapy with rural patients.

Clinicians practicing rural teletherapy must move beyond generic training and consider what additional experiences, knowledge, skills, and resources will be needed to equip them to be responsive to the realities of rural and remote patients. The additional preparation, training, experience, and resources needed to meet these challenges were reflected across participants' responses about what would have better prepared them for their critical event. Participant responses specifically included statements about needing lived experience in rural communities, the importance of being trauma-informed, and a desire for supervision by clinicians with rural experience. Others called for national rural and remote teletherapy standards, more discussions about unique ethical challenges, and additional training targeted at technical skills needed to navigate the complexities of this work. Contextual humility encompasses these responses, which span practice competencies across various levels and highlight how rural teletherapy competence requires a fundamental perspective shift, away from the assumptions and practice guidelines aligned with urban norms and toward increasing respect for the values, needs, and factors unique to rural living.

Clinicians can anticipate the complexities of rural and remote teletherapy by recognizing how contextual, cultural, clinical, ethical, technological, and administrative factors interact to create challenging clinical situations. Research has emphasized the value of integrating cultural bridges and local care coordinators to tailor teletherapy to the needs of rural Native veterans20. Additionally, research on low teletherapy utilization in a rural and remote Aleutian Islands community in Alaska suggested that the greatest barrier to rural teletherapy utilization is broken trust resulting from historical trauma36. However, many clinicians – especially those in private practice and those less familiar with life in rural communities – may lack the ability to employ cultural bridges, visit the communities where their remote patients reside, or fully recognize the many factors impacting their patients. This underscores the need for cross-contextual principles that integrate the teletherapy, rural mental health, and cultural competence literatures into a cohesive and articulated approach for clinicians who are doing this work.

Organizations supporting clinicians who are practicing rural teletherapy should attend to systems-based challenges such as improving technical support, adopting flexible clinic policies, and helping clinicians access training resources and supervision to assist with the complexity of rural and remote teletherapy. While the results of this study emphasized clinician-level adaptations to the complexities of rural and remote teletherapy, they also reflected how their work interacted with system- and infrastructure-level factors such as no-show policies and limited internet access. Similar challenges and recommendations have been noted internationally. In New Zealand, Werkmeister et al (2024) found that telehealth implementation and practice amid the COVID-19 pandemic were constrained by factors such as inadequate leadership, unclear policies, workforce shortages, and technical support issues37. In Australia, the Centre for Community Child Health (2020) emphasized capacity-building and infrastructure development alongside improving accessibility, acceptability, and awareness to expand their telehealth model for remote communities38. These publications underscore the importance of looking beyond individual clinicians to implement, deliver, and sustain teletherapy in rural and remote communities. The collective perspectives from participants in this and other studies suggest that implementing and sustaining rural teletherapy requires integrated attention at the individual, organizational, and policy levels.

Those working at the organizational and policy levels need to balance regulatory flexibility with clarity. Participants emphasized that flexibility was necessary to meet rural patients’ needs. Creating additional policies – such as national teletherapy standards, as suggested by some participants in this study – may complicate the service landscape by decreasing clinicians’ ability to adapt to unique situations if the regulations are ambiguous, restrictive, and/or not created with rural patients in mind. At the same time, clear regulations could help clinicians by providing guidance on issues such as privacy and confidentiality – a concern mentioned by multiple participants and reflected in the telehealth literature7. This reflects a tension: regulation is necessary to support quality health care, yet it can also constrain practical efforts to expand access in rural communities. Similar concerns have emerged in the telesupervision literature, where Noon et al (2025) argued that psychologist licensure policies regulating the use of telesupervision may limit rural workforce development, whereas regulatory clarity, at a minimum, could increase its viability39. Werkmeister et al (2024) likewise call for clarity in telehealth policy37. The medical field has echoed this concern with calls for structured approaches to assessing digital health policy implementation to avoid reinforcing health inequities40. These perspectives highlight the challenge of reconciling the need for clear yet flexible rural teletherapy standards – an issue the field must address for teletherapy to improve rather than perpetuate rural health inequity.

Finally, future research should develop a comprehensive rural teletherapy model that integrates data from clinical practice and patient outcomes across communities. This study was limited by its small sample size and the inclusion of only licensed clinicians within Alaska. Given the cultural, socioeconomic, and geographic diversity of rural Alaska and rural communities in general, a study that inquired about their patients' cultural, socioeconomic, and geographic variables would have helped participants articulate how specific aspects of culture and context influenced their work. Future research should recruit more participants and elicit more detailed data, potentially using interview-based or mixed methods. While this study focuses on clinicians’ retrospective self-reports, research focused on patients’ experiences is equally necessary to understand the most important elements of rural teletherapy.

Figure 1: A cross-cultural and contextual framework for teletherapy guidelines.

Figure 1: A cross-cultural and contextual framework for teletherapy guidelines.

Conclusion

Participants’ reflections on critical events within rural and remote teletherapy in Alaska revealed the paramount importance of contextual humility – the awareness of and responsiveness to situational and environmental forces alongside cultural, clinical, ethical, technological, and administrative considerations – as an additional guiding lens for practice. Participants also reflected a dynamic interplay between teletherapy as a mode of care and the clinical, cultural, and contextual factors impacting their rural patients’ lives. These conclusions reinforce existing teletherapy and rural mental health competencies while suggesting the need to integrate existing and new competencies into a cross-contextual framework. This research provides additional direction for teletherapy training, practice, and research while introducing basic elements of an integrative rural teletherapy model to support clinicians in recognizing and responding to the many forces shaping their patients’ lives.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

You might also be interested in:

2020 - Organophosphate exposure and the chronic effects on farmers: a narrative review

2014 - Correction, article no. 2907: Non-physician communities in Japan: are they still disadvantaged?