Introduction

Health promotion is a social and political process that aims to maintain and improve the health of individuals, communities and whole populations through empowering, participatory approaches1. Community participation is an essential component of health promotion and can be defined as a collaborative and dynamic process aimed at achieving community-identified outcomes2,3. A number of factors determine the effectiveness of community participation approaches when working with Aboriginal communities, including designing and implementing responsive strategies, Elders and community members leading project steering groups, and developing trusting partnerships between Aboriginal communities and health professionals4-6. A recent systematic review of community participation to empower Aboriginal communities found that approaches taken are still deficient in these factors and the strategies and processes used are not well reported. Levels of community participation fluctuate through the various project phases7, and experiences of community participation, from the perspective of participants, are rarely reported2.

Although community participation approaches are evidently appropriate in developing and implementing health promotion initiatives with Aboriginal communities, more evidence will assist in demonstrating their value4.

Smart and Deadly: a community participation approach to sexual health promotion

Sexual health promotion aims to leverage change at individual, community and policy levels to support positive notions of sexual health inclusive of gender, race, religion and ethnicity8. It was upon this premise that an Aboriginal sexual health promotion initiative was developed. Smart and Deadly was a community-led initiative to develop sexual health promotion resources with young Aboriginal people in north-eastern Victoria, Australia. A regional community forum and subsequent ‘yarn-ups’ (community discussions) to consider sexual health issues for young people were conducted in 2010–2011 and resulted in the formation of a local working group, with majority Aboriginal membership. Extensive consultation with Elders and Aboriginal workers followed. The initiative had three specific objectives: (1) to design, implement and evaluate a local sexual health promotion initiative with young rural Aboriginal people and their families, using the principles of Aboriginal health promotion practice; (2) to support young rural Aboriginal people to develop their own creative sexuality education resources; (3) to produce an audio-visual training resource for non-Aboriginal rural health workers engaging with Aboriginal communities.

The initiative included forums for Elders, parents and carers and a youth forum incorporating creative workshops in film-making, drama and dance and supported by artists, film-makers and actors. Young people were then invited to select dance, drama or film-making and to join a series of workshops over a 6-month period to create eight YouTube clips and rap songs about sexual health and respectful relationships. The filming for the documentary DVD followed this process and provides a narrative about the initiative through the voices of those involved.

The principles of community-centred practice, authentic participatory processes and respect for the local cultural context guided this project. This approach built on young people’s personal capacities, their interests and strengths, and skills in decision-making and leadership. A positive holistic approach to sexual health, sexual diversity and respect was promoted rather than one focused on risk. The project management team fostered active involvement with the health sector, schools, education departments, local councils, tertiary institutions and the broader Aboriginal community sector. Overall, 20 local partner agencies in health and education were involved and over 120 Aboriginal families and community members participated in aspects of this initiative. As the sexual health and respectful relationships arena can generate diverse and strong opinions, establishing and maintaining respectful and culturally appropriate processes was essential. Accordingly, the project team provided regular presentations with the local Aboriginal community working party, which provided opportunity for input, feedback and endorsement for each stage of the initiative.

A summative evaluation of Smart and Deadly was conducted in 2014. The aim of this evaluation was to understand the extent and depth of the Aboriginal community members’ participation in the initiative, the processes that supported particular forms of participation, and perceptions about barriers and enablers associated with community participation more broadly.

This article reports on factors that facilitated the community participation approaches undertaken in Smart and Deadly, focusing on how these were effective in achieving the project objectives and aims to further an understanding of factors that assist in establishing a culturally appropriate, community-controlled context in which community participation can occur6.

Methods

A qualitative summative evaluation was undertaken to understand changes to community and young people’s understandings of sexual health that occurred as a result of the Smart and Deadly initiative. The evaluation also sought to understand the community participation approach that underpinned the initiative and the associated interactions between the Aboriginal community and the health agencies that partnered in the Smart and Deadly initiative.

Focus groups and semi-structured interviews were conducted according to the specific roles of participants in Smart and Deadly: project participants, stakeholders and project partners, and project developers and designers. All participants were asked to comment on their involvement in Smart and Deadly and on the quality of the engagement and participation processes. Sampling was purposive, with participants recruited according to their role(s).

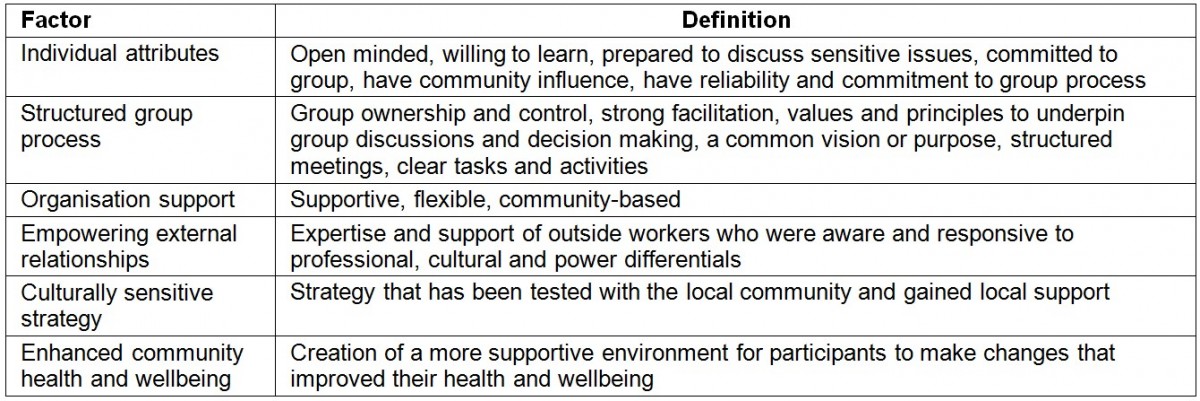

To understand the extent to which Smart and Deadly utilised culturally appropriate, relevant approaches to community participation with Aboriginal communities, evaluation findings were compared to the YARN model3 (Fig1). The YARN model was specifically created for planning and evaluating community participation strategies relating to sexual health promotion and comprises six factors that occur in a cyclic process (Table 1). These factors can work together or reinforce other factors within the model, as a means for understanding how community participation can be genuinely manifested.

Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed and de-identified to ensure anonymity and then organised for thematic analysis9. A deductive content analysis approach was used through comparing evaluation results to the YARN framework10. Coding and categorisation were undertaken individually and a final list addressing the study purpose was selected from the collection of discerned themes, following dialogue between the coding authors. Whilst the evaluation participants were not involved in data analysis, three members of the authorship team, who are Aboriginal, provided insight to the results from a cultural perspective. The voices and language of the participants have been used in reporting the results.

Figure 1: The integrated YARN model3.

Figure 1: The integrated YARN model3.

Table 1: Definition of the six factors of the YARN model3

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was provided by the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number 1339305) and the Victoria Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation through a letter of approval dated 20 March 2013.

Results

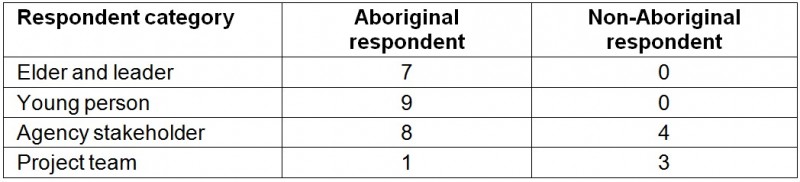

Thirty-two individuals participated in interviews, with four people participating in both a group session and a semi-structured interview. All of the Elders and program designers who participated at any level in Smart and Deadly volunteered for this study (Table 2).

The overarching theme that emerged from the evaluation of Smart and Deadly was that trust was the foundation upon which facilitators of community participation ensued. The identified facilitators of community participation were cultural safety and cultural literacy, community control, and legacy and sustainability.

Table 2: Type and number of interview respondents

Trust

Trust by the community in the project team was evident in the relationships between these groups. From the perspectives of two project team workers, trusting relationships stemmed from previous work together.

It helped a lot that I had worked in this area before and worked on projects where I guess I took a similar approach so it was very much about partnership but with the ownership clearly with the Aboriginal community. So there was definitely an element of trust with me that helped … (Participant 1, female, non Aboriginal project worker)

An Aboriginal member of the project team also described how his history with members of the Aboriginal community was important in encouraging the community to participate in Smart and Deadly:

I was connecting community to the program and especially the kids … I’d seen them go through all of primary school and I’d known their family … So I had that relationship with the community and the trust from like the professional working community as well … I think its nine or ten years I’ve worked in the community. (Participant 2, male, Aboriginal project worker)

Although length of community consultation time is not specifically mentioned in the YARN model, participants described it as being integral to building trust between the project team and the Aboriginal community.

They weren’t locked into trying to get it done in a year, or two years or three years. We weren’t running to their time schedule. They actually made time to make sure they were making the right contacts in the community. They took time to have lots of conversations. I think that was the key. (Participant 3, female, Aboriginal Elder)

The YARN model factors of ‘empowering external relationships’ and ‘individual attributes’ were exemplified in narratives that described reciprocity (mediated through respectful and ongoing consultation) and inclusivity, and collective building of trust and strengthened relationships, all indicators of community participation. The importance of relationships was articulated clearly by participants who stated ‘Aboriginal culture is based around relationships from persons, one to another, the land areas, it’s all based on relationships’ (Participant 4, male, Aboriginal Elder) and ‘If person A buys into the whole project then you’ve got their family and you’ve also got their friends who also buy in because it’s all about 'Well, if they do it and I trust their opinion, then I’m going to be involved too'’. (Participant 3, female, Aboriginal elder)

Cultural safety and cultural literacy

Cultural safety and cultural literacy, as facilitators of community participation, were the most significant subthemes identified. Both relate to the YARN model factor ‘empowering external relationships’. Cultural safety, which refers to an environment in which there is no challenge to, disrespect for or challenging of a person’s identity11 was a concern explicitly expressed by Aboriginal Elders. This concern appeared to be based on descriptions of previous experiences with other organisations, not connected to Smart and Deadly, that reflected passive participation; where decisions were made in isolation from and then imposed on the community. Issues discussed included a past history of culturally inappropriate research practices and subsequent exploitation through unsanctioned appropriation of community knowledge and (reputational) harm to the community. As a result, when discussing the planning and development of Smart and Deadly, Aboriginal Elders expressed the necessity to guard and protect young people that would be involved:

It was about how do we make sure that when research is conducted on our families that it’s going to actually benefit the community instead of tear us apart? (Participant 3, female, Aboriginal elder)

However, it was evident in the interviews that the project team were acutely aware of the need to provide cultural safety through recognising and addressing any professional, cultural or power differentials that arose. An Aboriginal community member noted a project worker’s responsiveness to issues that were raised:

… she [project worker] was really on the ball when she got any kind of feedback and changed, or did things differently or left it if it needed to be left or took it up if it needed to be taken up. (Participant 6, female, Aboriginal traditional owner)

Responsiveness to cultural safety was also evident in how project coordination issues were handled. This aspect of cultural safety reflected the YARN model factor ‘organisation support’ as these narratives identified agility, flexibility and effectiveness in project coordination and organisation, and deference to community voices. This approach reflected community participation in that multiple perspectives were able to be expressed in a safe environment:

... the [meetings] were open to anybody to give any opinion ... and it felt comfortable to do so. And you don’t always get that, you don’t always feel comfortable to say, ‘Well actually I don’t agree with that ...’ (Participant 7, female, non Aboriginal community liaison worker)

This theme was also highlighted by project team members; one stated:

... it was lucky that we found out about that [issue] when we did because it was very close to the date of [the event] and it could have been a real [disaster], someone pointed out to us, ‘if that persons says that, we will walk out.’ (Participant 8, female, non-Aboriginal project worker)

Grounded in cultural safety and the development of cultural competence through learning and experience, cultural literacy12,13 signifies a willingness and capacity to fluently navigate complex protocols and sensitivities for a given specific culture. Cultural literacy was described as being very important to the success of the project:

… you [Smart and Deadly] has a culturally literate external coordination [sic]. That was really important. Having a person that is able to speak and knows our community, has worked in it before, has already gained a level of trust, has already gained a level of acceptance and already knows the cultural cues from within our community … (Participant 6, female, Aboriginal traditional owner)

Another community member felt that Smart and Deadly provided opportunities for discussion between young people and their parents about sexual health in a culturally appropriate way:

… it was good to bring it [sexual health] back to the surface, to talk about it and have a cultural approach to this thing rather than just being a shame job or left to confident parents or for kids to find out themselves … (Participant 4, male, Aboriginal Elder)

Attributes of cultural literacy, expressed as respect, sensitivity and shared understanding demonstrated by the project team, were reported by community cultural liaison workers and Elders. For example, when it came to discussing aspects of sexual health that were men’s business and women’s business, the project team were aware of cultural expectations. One Elder noted:

… they [project workers] did … at times split [young people] up into separate [gender] groups to talk about stuff, which I think is culturally relevant and appropriate. (Participant 4, male, Aboriginal Elder)

Another Elder described the approach of the external project team more generally:

I thought [project worker] and their people, they were very respectful and they listened very carefully, took notes and everything like that but they were very respectful of what the Elders said … (Participant 9, female, Aboriginal Elder)

The respect that the project team demonstrated for young people ensured their voices and experiences drove ideas, particularly around drama and dance. As a cultural liaison worker noted, ‘... the respect they [the project team] had for the kids and the [Aboriginal] workers, was outstanding ...’ (Participant 11, female, Aboriginal Elder)

Community control

Community control related to the factor ‘structured group process’ in the YARN model, particularly in relation to group ownership and control. Community control was described as the preferred approach by the project team and as essential by Aboriginal Elders. They discussed aspects of the initiative, where outsiders and community worked together to develop and implement projects:

I like they did have the guts to sit back and let the community take control [in spite of them holding the project funds] because I can imagine how hard that would be for them … it did feel like a community run, community controlled program that we interacted with anyway. It didn’t feel like an outside thing. (Participant 3, female, Aboriginal elder)

What preceded community control were long periods of consultation between the Aboriginal community and the project team, which resulted in trusting relationships. One Aboriginal community member noted:

Consultation in our communities can take, and should take, at least a year for us to be fully comfortable and acceptable with what you are doing, why you are here and then allow you to come in and do it. (Participant 6, female, Aboriginal traditional owner)

This was echoed by other participants: ‘There was, from my point of view, there was continual, constant consultation …’ (Participant 11, female, Aboriginal Elder) and ‘… building rapport and trust and that happens in a relationship that moves forward, it goes slow but there’s that mutual understanding that maybe wasn’t there in the beginning.’ (Participant 4, male, Aboriginal Elder)

The long consultation periods enabled a range of community participation processes to occur. Community members described these as: (i) the establishment of a planning group comprising local Aboriginal community members, who drove the project and ran some of the meetings associated with the initiative; (ii) regular attendance of the project team at the local Aboriginal working party, which manages local affairs and decides upon and endorses local initiatives; (iii) attendance by the project team at meetings where parents and Aboriginal education workers were present to discuss the initiative and ask for opinions and feedback; and (iv) selection of a facilitator by the project team and Aboriginal community together, for aspects of the initiative that required one.

Legacy and sustainability

The YARN model factors of ‘enhanced health and community wellbeing’ and ‘culturally sensitive strategy’ were evident in the theme of legacy and sustainability, as demonstrated by several young Aboriginal participants ‘... we’ve been able to use it for our own purposes like jobs and school, which is very good.’ (Participant 12, Aboriginal young person, gender unknown)

Aboriginal community members also identified long-term dividends, effectively the project’s legacy, when they said:

A legacy is something that you leave behind as a positive thing. I see that it [Smart and Deadly] is a positive thing because if you just flip the page back five years in this community and what was going on with sexual health, with our teenagers ... and the inability to talk to them ... (Participant 6, female, Aboriginal traditional owner)

… we can now talk to our young people, our older people, all kinds of people in our community, about sexual health … that is one of the quality outcomes and it is also going to have a sustained impact. And what I mean by that is that people will start to talk, they will get more education or more knowledge from talking and therefore able to look after themselves a lot better. (Participant 9, female, Aboriginal Elder)

However, a number of participants discussed their frustration at the discontinuation of Smart and Deadly and the lack of sustainability after so much effort had been invested by the community and the project team.

Yeah, it’s funding you know, and that’s the frustrating thing about working in Aboriginal health or I suppose in mainstream health as well. You start something really good and then it just, no more money to keep it going and because it is not ... our core business ... I can’t do it in my everyday role. (Participant 13, female, Aboriginal worker)

Discussion

This article reports on factors that facilitated the community participation approaches undertaken in Smart and Deadly, focusing on how these were effective in achieving project objectives. The themes identified in this study provide an opportunity to better understand community participation in the Aboriginal context. This is important, given that community development and empowerment approaches have been recognised as a key strategy for tackling the complex and interrelated health issues evident within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities14.

Comparison of the Smart and Deadly evaluation to the YARN model found that a range of community participation approaches occurred, with trust the foundation upon which these were based. Trust between the project team and the Aboriginal community was founded on previous relationships between these groups and the long consultation periods preceding Smart and Deadly. This formed the basis upon which facilitators of community participation – cultural safety and cultural literacy, community control, and legacy and sustainability –were utilised. Overall, the type of community participation effected in Smart and Deadly was appropriate for the issue, available timeframe, the community concerned and the resources available2.

Comparing the evaluation results to the YARN model demonstrated that facilitators of community participation can be present within a range of themes and that community participation is a complex, non-linear process. Whilst theoretical models can be useful in articulating what needs to occur for a community participation process to be effective, the reality is that communities, issues and contexts are dynamic and somewhat unpredictable2. Establishing trust as the foundation for community participation created a context that could respond to evolving situations and relationships between the project team and the Aboriginal community.

Whilst use of the YARN model is highly productive in identifying many of the factors that enable community participation in the Aboriginal context, the importance of trust has been highlighted in this evaluation. Other studies have shown similar findings that good working relationships at a personal level between professionals and Aboriginal communities generates trust upon which project implementation can occur6,15. Conversely, previous experiences of community participation in unrelated projects appeared to reflect tokenistic approaches, resulting in some members of the Aboriginal community feeling suspicious about the motivations of outsiders offering to work together on health-related projects. This issue has also been identified by others where similar scepticism in the motivations of non-Aboriginal professionals in working with Aboriginal communities has been noted15.

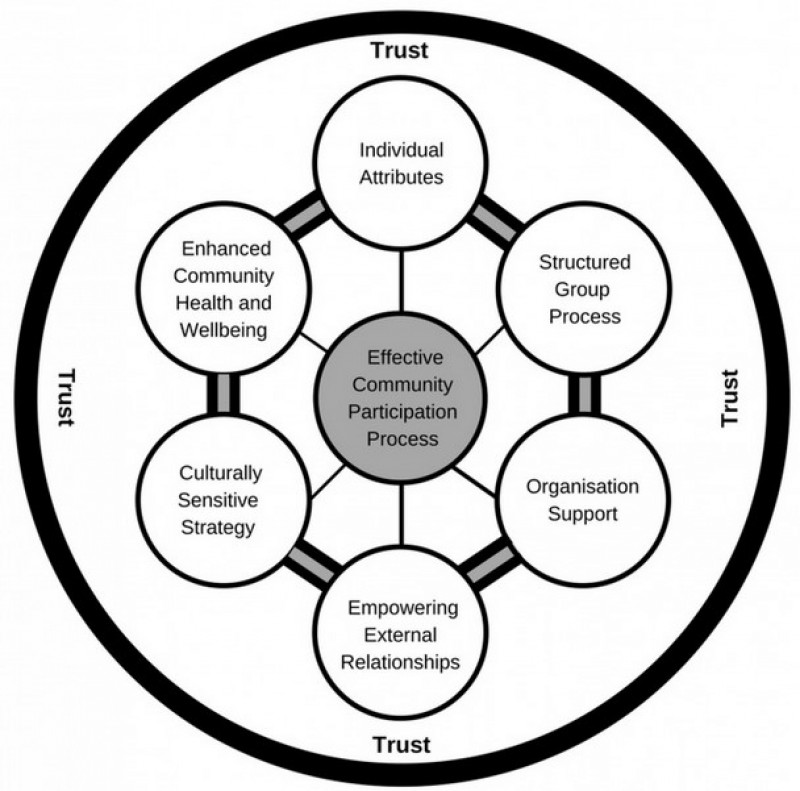

Trust has been identified as important for developing relationships between stakeholders16, and subsequently as critical to the success of Aboriginal health initiatives4, where the literature describes the importance of relationships in Aboriginal community partnerships with mainstream agencies12,17. As noted by Taylor et al16, Aboriginal community and mainstream partnerships can be challenging. However, trust appears to be a strong precursor to a community feeling that it has control and that this control will not be usurped further into the participation process. The finding about trust from this study could add a valuable component to the YARN model, extending it to include trust between Aboriginal communities and project workers as the basis upon which the YARN model factors are predicated. Figure 2 illustrates trust as a contextual element in which effective community participation occurs.

A more explicit focus on longer consultation periods with Aboriginal communities, with one of the aims being that of developing trust, would be beneficial in undertaking community participation. Such an approach may result in relationships and partnerships that are forged through cultural literacy, are grounded in cultural safety and that ultimately support community control. This may be particularly relevant when the issue is culturally sensitive, as in the case of sexual health when it is not readily discussed and may be related to specific cultural mores. Adding the finding of trust to the YARN model would then involve defining trust as a process occurring within the timeframe needed for the development of relationships between Aboriginal communities and project workers. Trust may help to establish a culturally safe environment in which factors seen to facilitate effective community participation can occur. The development of trust needs to be seen as a culturally appropriate initial step in developing a working relationship with an Aboriginal community that is focused on needs and outcomes identified by that community.

Although this study provides significant insight into community participation in an Aboriginal context, some limitations exist. This was a small qualitative study and therefore findings cannot be generalised because Aboriginal communities are heterogeneous in terms of cultural beliefs, connections to country and particular historical experiences.

Figure 2: The integrated YARN model with the addition of trust.

Figure 2: The integrated YARN model with the addition of trust.

Conclusions

Comparison of the Smart and Deadly evaluation to the YARN model found that trust was the foundation upon which facilitators of community participation occurred. These were cultural safety and cultural literacy, community control, and legacy and sustainability. This article provides specific detail in relation to how this was achieved and suggests modifying the YARN model to formally recognise the importance of trust in establishing approaches to community participation with Aboriginal communities.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to sincerely thank all evaluation participants for generously sharing their lived experiences.