full article:

Introduction

The shortage and maldistribution of health professionals in rural and remote areas remains a global problem, deterring a significant percentage of the population from access to healthcare services1. In Australia, there is a marked undersupply of healthcare workforce throughout regional, rural and remote areas2. Particularly, the numbers of general practitioners (GPs) in proportion to the population tend to decrease significantly with greater remoteness and rurality3,4. Given this recognised maldistribution and the consequent health outcome inequality5, the recruitment and retention of GPs in rural and remote regions has attracted considerable attention nationwide6,7.

At both the system and service level, multiple strategies have been adopted to improve rural access to health services8. To aid these policy responses and initiatives, many research studies have investigated the contributing factors behind the recruitment and retention of GPs in rural areas. For example, factors that are often reported as contributing to successful recruitment and retention of rural health professionals, including GPs, are financial incentives, clinical autonomy and community support2,9-11. In contrast, management issues, workload, spouse satisfaction and child education potentially impede GPs’ participation in rural practice12-15.

Despite the existing studies in this field, the community factors behind recruiting and retaining rural GPs are not fully understood16. This may be because the nature and impact of the pull and push factors that impact GP recruitment and retention vary across regions and contexts. There may also be interplay among coexisting factors that compound or relieve issues related to successful recruitment and retention. To address this multi-factorial and context-dependent issue, there is a need to extend understanding, in both breadth and depth, of rural communities’ assets and capabilities that impact GP recruitment and retention. It is imperative to go beyond mere identification of major community factors, to the elucidation of their underlying reasons and distinctive features. Such in-depth insights are vital for the development of a comprehensive approach to improving and sustaining rural GP workforce.

By presenting the qualitative findings from a previously published pilot study, the aim of this article is to provide a much broader and comprehensive contextual understanding of the experiences and insights. The study explored health service representatives’ perceptions of advantageous and challenging factors important in GP recruitment and retention in the Hume region of Victoria, Australia16. These advantages were associated with transfer arrangements, nursing workforce, perception of quality, allied health workforce, and GP workforce stability. Conversely, the challenges were linked to spousal satisfaction, schools, access to shopping or other services, and on-call or practice coverage16,17.

Methods

The pilot study utilised the Community Apgar Questionnaire (CAQ)17 to examine the community factors in GP recruitment and retention in the Hume region, and was framed by a concurrent triangulation mixed methods design to confirm and cross-validate research findings18. This research design is one of the more simple mixed method designs, where the dominance is neither given to the qualitative or qualitative methods, but data are merged in the interpretation stage of the study to strengthen the knowledge claims of the research18-22.

The CAQ consists of 50 factors, categorised into five classes: geographic, economic, scope of practice, medical support, and hospital and community support. Three open-ended questions were also included to validate the selected factors and capture richer details on the researched issue16. It was administered using face-to-face structured interviews with a total of 40 health service representatives, including 14 chief executive officers (CEOs), 14 directors of clinical services (DCSs), and later interviews were followed up with seven general practice managers and five GPs. The interviews were conducted separately, in private locations, and had an average duration of 35–60 minutes.

Recruitment of participants was achieved by inviting all district health facilities and bush nursing services and general practices associated with the health facilities in the Hume region to participate in the study. Initial contact was made by telephone and email. Among the identified services, 14 health facilities and nine general practices participated in the study. Some general practices were co-located with or were integrated as part of the health service. Running the CAQ required a minimum of a two individuals from each service to participate, who had responsibilities for recruitment and retention activities16,17.

The principal aim of the CAQ was to assign numerical scores to the qualitative ratings of the 50 community strengths or challenges and their relative level of importance to recruiting and retaining GPs in the rural community16.

Four-point Likert scales were used to score the 50 factors in terms of their advantage or challenge to the community (major advantage = 2, minor advantage = 1, minor challenge = –1, major challenge = –2), which was weighted according to their perceived importance (very important = 4, important = 3, unimportant = 2, very unimportant = 1). These were then scored using the following algorithm to create a community asset and capability measure that ranged from –8 to 8 where higher scores indicated more developed community asset and capability in terms of GP recruitment and retention16:

(community advantage/challenge score) x (community importance score) = CAQ score

Although the CAQ’s focus was to numerically ascertain a community’s advantages and challenges, the structured interviews also provided an opportunity for the participants to discuss each factor in detail. As such, the study encompassed aspects of phenomenology where participants moved beyond the structure framed by the CAQ to share personal beliefs, situations and experiences that created in-depth meaning and greater contextual understanding than initially anticipated23-25.

All interviews were audio-taped with consent. Qualitative data was generated from the extended responses of the respondents to these structured interviews. The qualitative data collected from the interviews were transcribed and descriptive coding was performed to help with the data identification. Accordingly, the participants were coded on the basis of their role within the healthcare organisation (CEO, DCS or GP) and their interview order (1, 2, 3 and so on). An essentialist or realist paradigm and a deductive thematic approach were selected to be used in the study to allow a simple method of systematically identify recurring themes, behaviour and experience, which then became a description of the phenomenon26,27. The analysis was conducted with these ‘additional’ comments and stories and were triangulated according to the pre-determined themes in the CAQ, while allowing for emerging themes to be added where applicable.

Overall, the process assembled singular and small ideas or experiences from each participant and combined these to form a comprehensive and rich understanding of the phenomenon or experience. As information emerged from the data, it was placed into the corresponding pre-classified or newly identified themes. The next step was a process of breaking these clusters of data into smaller subthemes and then into overarching themes26,28. The relationship of these themes to the literature was then examined to form an interpretation and conclusion27-29.

The analysis revealed substantial and additional information that was central to the 50 factors. Nevertheless, only comments and stories relating to the top advantages and challenges, as determined by the quantitative numerical scores, are presented and discussed qualitatively here. These top-rated factors received a consistently large amount of additional explanations, elaborations and/or relevant strategic approaches to improving rural GP workforce.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study was obtained by Albury Wodonga (HRECAW409/15/4), Northeast Health Wangaratta (HRECNHW160) and the Goulburn Valley Health (GVH09-15) human research ethics committees.

Results

The face-to-face interviews with the health service representatives included comments related to the primary advantages and challenges of the recruitment and retention of GPs in the Hume region16. In most cases, there was little variation in terms of the themes that emerged across all the different groups that were interviewed. The comments provided not only the identification of, but also explanation for, and elaboration on, the strategic approaches to those pull and push factors, as outlined in Table 1. Thus, the analysis demonstrated that the comments among many of the participants did provide contextual data regarding the multifaceted issues of recruiting and retaining GPs in rural regions extending beyond the factors themselves.

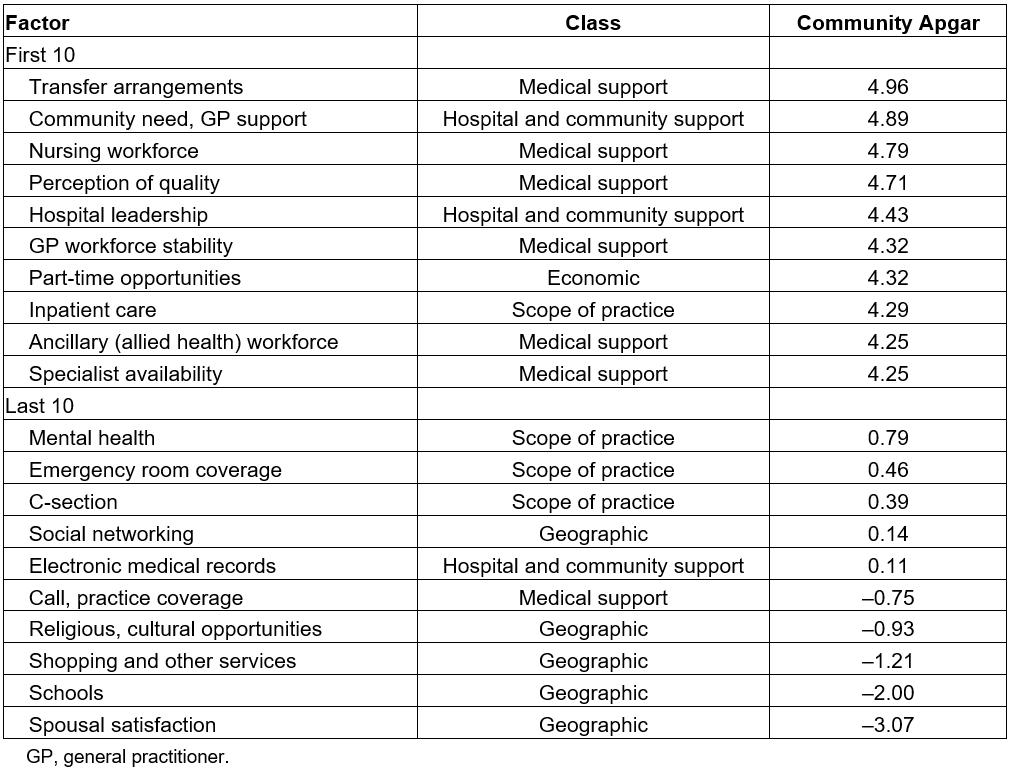

Table 1: First 10 and last 10 factors, their class and overall Community Apgar Questionnaire scores

Advantages

As identified by the respondents, the major advantages were mainly associated with the classes of medical support (transfer arrangements, nursing workforce, perception of quality, ancillary staff workforce and general practitioner workforce stability), hospital and community support (hospital leadership, community need/general practitioner support) and economic factors (part-time opportunities and income guarantee).

Medical support factors: Transfer arrangements were highlighted as appealing to GPs, especially when well-developed protocols were in place to ensure critically ill patients could receive greater care as needed. Given the lack of many specialist services at rural health facilities, GPs would ‘want to know what the process is and how it’s going to happen’ (CEO-10). A standardised procedure for transferred arrangements would be a reassurance to GPs that they can ‘move them on’ (CEO-12) without unnecessary stress or frustration. Some typical comments were as follows:

It’s a major advantage, because they need to be able to get someone out if they need to. (CEO-02)

I’m working with [names] and our GPs in setting up five standard clinical pathways … So, we have very good transfer arrangements. It’s a major advantage. Our GPs really appreciate it, because they’re well supported. (DCS-11)

Regarding support from other medical staff, having a good nursing workforce was perceived as a crucial pull factor in recruiting and retaining GPs. The main reason for this was thought to be the tight-knit interdependence between nurses and GPs in providing quality care to patients, especially in small rural facilities. If the capacity of the nursing staff was ensured, and their relationship with GPs operated on trust and open communication, the respondents saw that as advantageous to retaining GPs. In some cases, the nursing workforce was depicted as one of the deciding factors in GPs’ decisions to stay or leave.

Having a good team is an advantage … because some people won’t go to certain places if they don’t like the nursing staff. (DCS-04)

That’s another strong one. We’ve got good nurses. They’re really essential. (GP-01)

I think as far as the way we operate with our nursing staff – with the support they give to the GPs, with the care planning in chronic disease management, which takes a lot of the workload off of the GPs … Also, just having that support … They’ve got a nurse who’s got 30 years of experience standing next to them. So, I would say that’s very important. Especially the young ones coming in, they like to know they’ve got the support. (GP-05)

In addition to the nursing staff, having a good ancillary staff workforce was identified as a major advantage. The respondents especially emphasised the role of allied health staff, such as occupational therapists, physiotherapists, social workers, speech therapists and dieticians, in assisting GPs in providing well-rounded quality health services. The existence of these allied health staff within a facility would facilitate the referral pathways and provide GPs with a supportive working environment. Well-staffed and skilled allied health workforce, therefore, was felt to contribute positively to GP recruitment and retention. As stated by some respondents:

We’ve got a full-time physiotherapist, and she’s fabulous and the doctors love her. She’s great. We have a visiting speech therapist and dietitian once a month. I think the services we provide are pretty good, compared to other places, so the doctors think that’s good. (DCS-11)

We’ve got those services within the organization, and that is important. And it is a major advantage, because the referral pathways here are quite easy. You’ve got to have district nursing, [and] allied health ... That’s all a big advantage from the recruitment perspective. (GP-07)

Apart from the current workforce condition, GP workforce stability in a facility’s employment history was frequently discussed as a critical factor in attracting GPs. According to one respondent, ‘a high turnover of doctors can be a red flag’ (CEO-10). Interested GPs would link high turnover with potential issues. On the other hand, a stable workforce was associated with high job satisfaction in a good working environment. In addition, stability was felt to reassure new GPs of the available support for an easy settling-in as, reflected by two participants who stated:

It’s very important for new doctors coming in to say, ‘Okay, there is some stability here’. The other reason it’s important is not just that turnover might suggest issues, but that they know that people are going to be around for a while and the load won’t necessarily fall on them ... That gives them a feel that they’ve got time to settle in and get to know the place, and they’re got seniors to go and talk to if they need to. (GP-08)

I reckon that’s a major advantage, because that’s what I do get asked in a lot of interviews as well, ‘Is your registrar staying on?’ They’re asking to see if people want to stay … So, I’d say that’s very important. (GP-05)

Perception of quality, or the reputation of the health facility as a provider of quality medical care, was also identified as an advantage in various communities for the recruitment and retention of GPs. As a respondent stated, ‘We have a very good reputation in the community, so that’s probably a major advantage’ (GP-08). This perception of quality was believed to be shaped by various factors, including being up to date and modern, being well-organised and properly presented, and ‘doing very well in what we do’ (CEO-05). The positive reputation built by a health facility was considered important in attracting GPs because GPs would feel comfortable working in a well-run facility with a high level of quality care and they just ‘don’t want to work in a dodgy place’ (CEO-01).

Hospital and community support factors: With regards to hospital and community support, the two factors of effective hospital leadership and high community need/general practitioner support were emphasised as contributing positively to recruiting and retaining GPs to these rural facilities. Hospital leadership, including CEOs and other levels of management, were believed to be highly advantageous when there was ongoing collaboration, mutual support and open communication with GPs. Commenting on this, some respondents noted:

The relationships are critical. You’ve got to work on those to make sure. It’s also around developing those services and the consultation with the medical officers to make sure you have their support and that you’re moving in the right direction and they feel part of the decision-making. (DCS-07)

It is a major advantage, because you have to be able to have good working relationships. In rural communities, if you’ve got an adversarial relationship with your GPs, you’re holding to nothing. (CEO-12)

Community need and support for GPs emerged as an important factor not only from a business perspective, but also from a family perspective. Specifically, the respondents repeatedly emphasised the fact that a strong support from the community would be a guarantee for GPs’ income as well as for their families to comfortably settle down and get engaged in the community after their relocation. The following comments reflect this:

If they can see that there’s a need and there’s a revenue stream and they’re committed to a community, they’ll do it. (CEO-02)

It’s going to be very important for a new GP. I mean, if they’re bringing their family here, they’re not going to want to be outcast. (CEO-10)

It’s important to the success of that person staying here, because if they’re not going to get the consultations, they will go elsewhere. It’s important that the community knows about it and supports it by knowing that it’s there, and important for the practices to refer. That’s pretty important to the sustainability of that. (CEO-11)

At Christmas time, you should see. … the presents that come in here. And we have farmers come in with fruit. And we get a lot of ‘thank you’ cards … I don’t know if you noticed the flowers that [GP name] herself got from a patient last week. It made her cry. (GP-02)

Economic factors: Part-time opportunities and income guarantee were two economic factors that the respondents considered to be greatly advantageous. Throughout the conversations with the respondents, there was a clear emphasis on the availability of part-time options as a pull factor to GPs, ‘particularly for women, it’s a major advantage’ (CEO-01). This is because working part-time would allow them to have a better work–life balance, ‘if you’re a young mum and a doctor as well and wanting only two days a week’ (DCS-11). For more senior GPs, part-time work could provide them with opportunities to contribute to the community without the pressure of full-time work. For junior GPs, it would facilitate their further study or their exposure to more varied experiences elsewhere. Overall, the respondents’ comments depicted part-time opportunities as appealing to various groups of GPs.

If a husband and wife team comes, they could both work part-time and have a great life. (DCS-03)

Probably for the reasons that some of them are relatively junior and would want [life] experiences elsewhere as well. I know a couple had young families, so they want to work part-time and not full-time. I think having part-time opportunities is important. (CEO-11)

One of our doctors is 73, just retired, and she worked one day a week. Used to work 3 days a week. Lives 100km away and used to drive up here … The fact that we can do it would be a major advantage, because I’d say a lot of people wouldn’t allow that. (GP-04)

It’s probably a major advantage. A lot of them don’t want to work full-time. It’s very important … You know, because we’ve had quite a few say they want to drop half a day for study or one’s just had a baby. He wants to drop a day to spend time with the family. (GP-05)

Coupled with the choice between full-time and part-time work, income guarantee was considered to play a part in attracting GPs. This was felt to be especially important for younger GPs, although stable income would be significant to all interested GPs when it involved relocation to a rural area with the whole family. The reason for this was ‘they want to know that they’re going to have a certain income and maintain a certain lifestyle, with wife and children’ (CEO-14). Income guarantee would usually be offered in the first few months, but some facilities could make it an ongoing commitment, which was considered to be very important.

Initially, for the first two or three months, they are guaranteed a certain amount of income. After that, it’s a percentage of what they earn. The more patients they see, the more money they earn. It’s a major advantage and important. (CEO-05)

I guess it depends how important money is to you, but I’d say it’s a major advantage as a junior doctor. (DCS-11)

If I was a new doctor, I would ask that. Absolutely. If it were available, that would be an advantage. (GP-03)

They are guaranteed minimum income per day. That’s extremely important and a major advantage. It’s ongoing, as well. A lot of contracts will do that for the first six months or the first year, but ours is an ongoing commitment to do that. (GP-07)

Challenges

The major challenges of GP recruitment and retention were largely linked to the geographic class (spousal satisfaction, schools, shopping and other services, religious/cultural opportunities and social networking). Other major challenges were in connection with call/practice coverage, obstetrics/caesarean section, emergency room coverage and electronic medical records as outlined in Table 1.

Geographic factors: The geographic factors most strongly believed to impact negatively on recruiting and retaining GPs in the Hume region were spouse satisfaction and schools. According to the respondents, the wellbeing of family members was among the top concerns of GPs. As a respondent commented, ‘your family and your spouse being happy in the decision is very important’ (GP-08). For that reason, limited employment opportunities for their spouses, identified as the most important concern in terms of spousal satisfaction, and limited education choices for their children in the region, were major push factors.

Many respondents expressed their concern for the shortage of jobs for the spouses of GPs, which could mean their certain withdrawal from the offer or intention to leave after a short period of time. ‘I reckon that would be the number one biggest problem, and I reckon it would be the biggest challenge for recruiting’ (CEO-09). If the spouses were working in the specialised non-medical professions, the opportunity of getting suitable employment within the local area was believed to be very difficult. If they worked in the same healthcare area, it might not be as challenging. However, even when spousal employment could be guaranteed, the potential feeling of being isolated could pose a threat to GP retention.

In this town, I would say it’s a major disadvantage. It depends what they’re into … If they’re a nurse, we’ve got a job for them, but if work in [information technology] or as an engineer, it’s limited. (CEO-14)

I think that would be a challenge, unless they are in health themselves. If not, where do they go? … so they’d have to be travelling. (CEO-10)

We’ve had some wonderful overseas trained doctors, but the spouses and families would feel quite isolated in this community. Hence, they go to the bigger centre. (GP-07)

With the lack of school choices, a widely perceived characteristic of rural regions like Hume, schools were frequently discussed as a challenge. Particularly if the GPs have school-aged children, ‘education is often something that is brought up when you’re recruiting doctors into towns’ (CEO-02). Many respondents believed doctors preferred to send their children to private schools, which were often not accessible, especially when children were of high school age. ‘Doctors are well-educated themselves, so have a keenness to make sure that their children are well-educated …’ (GP-01). Consequently, if they were not comfortable with their children commuting to a private school by bus or attending a boarding school out of town, they would choose to leave. Other comments included:

There are good schools, but not the elite private schools, so we have lost doctors. (CEO-01)

In terms of private education, which seems to be the common thing, there’s not much of a variety around here. It would be a challenge. I’d say major, because most of the doctors that are coming to the area are young. (DCS-11)

I’d say that if I really cared about my kids’ education that would stop me coming here … I’d say it’s very important for GPs with kids. (GP-02)

There are schools available, but I guess the travel for the private if you want the secondary school is probably the issue … So, the retention, it makes it really hard. (GP-05)

In addition to spousal satisfaction and education, difficulties in ensuring the wellbeing of the whole family were also discussed in terms of the shortage of shopping and other services. In most cases, major shopping centres were reported to be at least half an hour or an hour away. It would be even more challenging for GPs from another cultural background due to the unavailability of cultural foods within the region.

There’s nothing here, so it’s a major issue for them. (DCS-07)

I think they’ve got to access outside of here, because there’s not much in here ... All the staff will either go up or they’ll go down to the northern suburbs of [major metropolitan city] and do their shopping. (CEO-11)

It’s very limited. You can’t get a coffee here. Not before 10, and only on certain days … I think it’s a major challenge. There’s the little [supermarket], but if you want something … If you’re an Indian or an Egyptian person, seriously, the [rural supermarket] is not going to have the groceries that you need. (CEO-14)

GPs from a different cultural background could also encounter the frustration with limited religious and cultural opportunities, from the view of the respondents. Although the level of negative impact was felt to depend on each individual’s religious and cultural needs, this shortcoming could certainly pose a challenge for GP recruiters. Apart from Catholic and other Christian denominations, opportunities for all other religions were described as being inadequate. This lack of breadth in cultural opportunities here ‘does mean that that group has to go outside to meet their religious and cultural needs, which can be tricky’ (CEO-02). While not being depicted as a make-or-break factor, it could, along with other challenges, increase international GPs’ intentions to leave.

In terms of non-Christian religion, there's very little available. Well, there's nothing available, as far as I’m aware ... A devout Christian probably wouldn’t be a problem, but a devout Muslim. That could be difficult for them. (GP-08)

There are no cultural opportunities here, so that’s a challenge and a big disadvantage. (CEO-04)

If you’re a Jew, if you’re a Muslim, if you’re a Hindu. I’ve got a lot of Indian staff here. Their ability to worship is limited. (CEO-09)

For GPs with an Australian background, another challenge brought about by the geographic barrier was social networking. Many respondents highlighted the difficulty of GPs in establishing professional networks in the area because there were not many doctors around. As some respondents commented:

We don’t have a big network of doctors and other professionals in the town, so for GPs to have a social network, it can sometimes be a bit limiting. (DCS-02)

It’s a challenge. They’re socially isolated, because there’s not a lot of them. (CEO-05)

In the small communities, it’s very important, because they run the risk of being isolated. That connectedness is usually very important to those people. (DCS-07)

When it comes to social networking with community members, GPs were believed to face challenges as well. Being a doctor in a small town would mean a blurred boundary between work and social life. Social exchanges between GPs and community members, whether it was at a supermarket or a cafe, would be related more or less to their work as a doctor. ‘There’s just no escape’ (CEO-14) because ‘they walk down the street and half the people are their patients’ (DCS-02). This fact of being easily recognisable as a doctor was described as being detrimental to GP’s social networking, hence a negative recruitment and retention factor.

We’ve got a young doctor who came to us and she’s living in town. One of her constant struggles is having the social networks, because if she goes to the [sporting] club, people see her as a doctor and want to talk about stuff, yet she needs a social outlet. It’s tricky. (GP-01)

It’s a disadvantage … because people stop you on the road and the supermarket, asking, ‘What has happened to my report?’ (GP-03)

Scope of practice factors: Regarding scope of practice, emergency room coverage with on-call requirement was described as challenging. For example, some GPs would be discouraged by the fact that they ‘get called out in the middle of the night’ (CEO-10). In some cases, issues with the emergency transfer procedure could make it more frustrating. As a respondent commented, ‘That’s probably a major challenge at the moment, just in terms of their transfer practices, so we’re working on that’ (CEO-03).

Obstetrics, and particularly caesarean section, was found to be a special challenge whose negative impact was clearly observed whether or not it was part of the available services. On the one hand, if the facility did not have the capability to support obstetrics or caesarean section, it could be a push factor for those GPs with an interest in that clinical exposure and in extending their scope.

We’ve had some that have come here for an interview and clearly want to be involved in obstetrics. The moment they hear that’s not the case, they’re not interested, so it is a big factor. (GP-01)

We don’t offer it. We do have a problem. A lot of the registrars coming through, they have a lot of interest in that area, and we can’t offer it. (GP-05)

On the other hand, if obstetrics and caesarean section were available at the facility, there would be a real challenge in recruiting GPs with the appropriate skills or interests. As a respondent stated, ‘If you’re offering obstetrics, it would be a major challenge to recruit someone’ (CEO-12). Even when GP obstetricians could be found, keeping their interest, maintaining their skills, and retaining them could be difficult due to the lack of client demand in ‘an aging community with very few births’ (CEO-04). Others stated:

If they wanted to continue their skills, they wouldn’t come here. It would be a major challenge, I suppose. (DCS-13)

I think it would be a challenge, because the work wouldn’t be there, and I’d be worried about the person’s skills. (CEO-14)

Other factors: With respect to medical support, the respondents tended to stress the challenge of on-call/practice coverage. From their observations, on-call/practice coverage could present a disincentive to most GPs, simply because ‘they don’t like on-call’ (DCS-06), or ‘they detest it’ (CEO-10). Due to the small number of GPs in a town or area, ‘it is an issue, because these few have to be spread [to cover the on-call]’ (DCS-07). Being on-call frequently would leave a disturbing impact on their home life and their family, leading to possible pressure, frustration, weariness and burnout. The following comments clearly underline this challenge.

On-call is very important and probably a major challenge. I think that’s the thing that puts most people off from going into the bush. (GP-08)

If you’ve only got one, two or three GPs, it’s horrendous for them, because they’ve got no work–life balance, and that’s so important. (CEO-06)

With more GPs, you can spread the load, but if you’re one and there’s a large on-call, it’s burnout. (CEO-14)

They do have to be on-call. The ones that have been doing it for 30 years are sick of it, and the younger ones … It’s got rocks on it, type of thing. Working full-time is enough for them. (DCS-13)

Another challenge of GP recruitment and retention was observed in the absence or under-use of electronic medical records (EMR), a hospital and community support factor. While EMR was reported to be successfully implemented at many health services, quite a few respondents mentioned their struggle with the traditional way of managing medical records. ‘We haven’t got the IT here. It’s a real issue. It’s our biggest challenge’ (CEO-04). According to these respondents, the lack of an efficient EMR system could negatively affect their provision of quality care due to possible miscommunication and delay.

We don’t have electronic medical records. In aged care we do, but we don’t in acute, which is backwards, but anyway … It’s a region [wide] issue in not having proper electronic stuff and no one talks to each other. (DCS-04)

The issue is, when you don’t have an integrated record, you’ve got multiple hard copies or you’ve got a dislocation between what happens here and what the practice sees. (CEO-11)

Suggested strategic solutions

The suggested solutions provided useful information for the development of initiatives to facilitate GP recruitment and retention in the Hume region. Most of the recommended strategic actions were directed towards addressing the identified challenges.

To deal with spousal satisfaction, which was the most common refusal reason as observed by the respondents, it was highly recommended that efforts be made to incorporate spouses in recruitment strategies.

For a lot of people, if their spouse can’t get employment, they won’t come. Often you’ve got to look at [the GP and spouse] as a package ... I know there are times that we’ve made jobs in order to be able to attract those people, so that’s the level of importance that we place upon it. (DCS-07)

To offset the geographic barriers such as limited schools, shopping, and religious/cultural opportunities, a practical solution would be to ‘sell your strengths’ (DCS-03) and ‘promote the type of lifestyle that they would have here’ (DCS-13). In doing so, the aim was to attract GPs with a genuine interest in what rural communities could offer. The provision of an intern program, for example, could be a step towards this goal, in which the overall emphasis was put on finding the right fit for rural communities.

I think identifying the key things we do well and how that gets promoted. If [names] are selling something at the college, the hospital needs to be complementing that, so we need a bit of a joint sales pitch coming from different perspectives … on the same wavelength. (DCS-03)

Provide an intern program that has a GP focus. There’s been a very strong clinical training to enable that. (CEO-01).

In addressing the challenges associated with GPs’ scope of practice and on-call responsibilities, the recommended solutions included building a stronger nursing and medical workforce to provide GPs with the necessary support. The introduction of nurse practitioners or the rural and isolated practice endorsed registered nurse (RIPERN) role within certain health services was a typical example of this approach. It was felt that RIPERNs could effectively alleviate the on-call responsibility of GPs.

What we’ve done to improve the on-call situation is to have more trained nurses. And also having ‘remote doctor on-call weekends’, I call them, which means the on-call for the urgent care for the weekend is done via … video consultations. I mean apart from the fact that they also line that up with the rural ambulance. (GP-08)

I think something that the health service can do for the GPs is to ensure our skill set and capacity is good, so that’s the RIPERN stuff. (DCS-06)

Some of it is by other workforce models. The RIPERN, the nurse practitioner. Those people are rostered to work anyway, and if their skill base is higher then it’s a good support for those medical officers. (DCS-07)

Establishing closer partnerships with other health services was also highly recommended. Collaborative coordination of workforce, resources and professional development was believed to be beneficial for all involved healthcare facilities.

I think probably some of it comes down to building partnerships with other health services, so if we do recruit a GP that wants to do some obstetrics, they can go up the road a day a week. (DCS-02)

I think we could be in collaboration with our more central [regional] health services to come up with ideas ... We could have fantastic opportunities for professional development and sharing of workplace resources. (DCS-05)

I think it’s the relationship with other health services. You know, ‘I’ve got a GP five days a week. He wants some [Accident and Emergency] experience. Can he come and work in your [Accident and Emergency] one day a week?’ (CEO-10)

For GPs who wish to do further training or ongoing education, potential solutions would be the provision of more choices and flexibility. As emphasised by the respondents, hospital leaders could attract and retain more GPs with open communication and responsiveness to their needs.

In terms of professional development … they can do exchanges and have extended leave. I’m sure all these flexible work options are in place. Now with the internet, they can study remotely or take a leave of absence and go and work in wherever they want to for six months and come back. Perhaps just be a little bit more responsive and innovative as communities, and do more within what we’re able to do. (CEO-13)

Discussion

The qualitative findings illuminated the most important advantages of recruiting and retaining GPs in the Hume region, which were mainly linked to medical support, hospital and community support, and economic factors.

With regards to medical support, the ease of transfer arrangements was emphasised as a crucial factor, given the typical limited access to specialists in rural facilities. This is consistent with the findings of other researchers30-32, who highlight the importance of well-developed inter-hospital transfers in improving patient outcomes. The reassurance that critically ill patients have easy access to higher level care could minimise the stressors for rural GPs. Other factors such as nursing and ancillary staff workforce were indicated to be essential in attracting and retaining GPs if they could demonstrate capacity in quality care and ability in handling relationships. Similar findings can be found in the literature33-35, with indications that interprofessional team cohesion built on trust, support and reciprocity could reinforce GPs’ intention to stay. The present study also highlighted the positive impact of GP workforce stability36 and the reputation of a facility as a quality healthcare provider17 on GP recruitment and retention.

In terms of hospital and community support, this study confirmed the major role of hospital leadership. Specifically, hospital leadership characterised by ongoing collaboration, mutual support and open communication with GPs was described as contributing positively to recruiting and retaining GPs in these rural facilities. This is in alignment with the literature about the relationship between health service management and the retention of rural health professionals36-40. In addition, community need/GP support was found to be advantageous for attracting GPs, further supporting previous health workforce findings41-43.

Economic factors such as part-time opportunities and income guarantee were also depicted as appealing to GPs in the Hume region. This finding reinforces the existing body of literature36,44-46 and offers implications for the use of flexible work arrangements and financial security in stabilising rural health workforce.

On the other hand, the identified challenges of GP recruitment and retention in the Hume region were mostly related to geographic factors, many of which are similar to those experienced by other rural health providers. Spouse satisfaction and schools are commonly reported as having a great impact on health professionals’ intention to leave or stay40,47-49. The lack of social or employment opportunities for spouses and limited quality schools for children seem to be a persistent concern, which highlights the need for the inclusion of these factors in strategies to address the high turnover of GPs in rural areas41,50.

The shortages of shopping/other services, religious/cultural opportunities, and social networking are often described as challenging for health professionals, including GPs, working rurally40,42,51. Other notable challenges were in connection with call/practice coverage40,51,52, and electronic medical records. All of these challenges are associated with the region being geographically isolated, a signature characteristic of rural areas.

Potential countermeasures against these limitations would be to promote rural strengths, targeting GPs who are genuinely attracted to the rural lifestyle and practice46,52. Accordingly, there has been a strong support for recruiting rural-raised and community-oriented applicants to medical school, rural residency and rural practice9. The rural pipeline, in which rural healthcare facilities collaborate with educational providers in offering rural-oriented clinical training, is often cited as an effective approach in this direction7,53-55. Other practical solutions would be to strengthen the rural nursing and medical workforce, as well as to foster partnerships with other health services for mutual benefits in shared workforce and resources.

Based on the findings of this study, the development of short-term and long-term improvement plans, and marketing strategies for successful recruitment and retention of GPs, would most effectively encompass a number of approaches. These may include hospital leadership, at all levels of management, promoting collaboration, mutual support and open communication with GPs. Importantly, being flexible and responsive to GPs’ needs will assist rural practice participation, such as providing full-time or part-time opportunities that encompass choice around contract and salary options. This also includes developing standardised clinical practices (eg transfer arrangement procedure or EMRs) and establishing a capable medical workforce. Upskilling the nursing staff, including nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists and RIPERNs, may also be beneficial to ensure they can adequately support GPs in a collaborative team-based approach to healthcare provision.

The wellbeing and satisfaction of family members have been found to be vital factors affecting GPs’ intention and decision to work rurally. Therefore, GP recruitment and retention strategies must encompass a holistic approach to address and incorporate spousal employment and children’s education. Consideration should also be given to the establishment of partnerships or region-specific agreements with larger centres or services for shared workforce and resources. For example, the use of tele-health or collaborative after-hour and emergency care would reduce the stressors for rural GPs, and at the same time increase access to special care for low-resource rural communities.

Conclusion

Through this qualitative study, a number of modifiable and non-modifiable factors were identified as being either highly advantageous or challenging for the recruitment and retention of GPs in the Hume region. The underlying reasons for and nature of those advantages and challenges were revealed through participants’ observations of the local health service providers. These findings reinforce the fact that the influencing factors behind health professionals’ decisions to stay or leave are complex and multifactorial, which confirms the need for a flexible multifaceted response to improving GP workforce in rural areas. The suggested solutions from this study could inform decision-making, particularly in terms of how best to address the GP workforce issue within the scope of available resources and capacity.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by the Australian Government Department of Health through the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training Programme. Initial funding for the development of the critical access hospital Community Apgar Program was provided by the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, Bureau of Rural Health and Primary Care. The authors would also like to acknowledge the research assistance provided by the Australian Academic and Research Advancement Services, and the Family Medicine Residency of Idaho for their contribution.