Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) is a discussion exploring the issues pertaining to a person’s end-of-life experience1. It involves an understanding of their medical condition, belief networks, values and preferences1, and empowering them to communicate these desires for medical treatment as they begin to lose capacity2,3. The concept of ACP revolves around the principles of autonomy, legal consent, dignity and avoidance of suffering1,4,5. An advance care directive (ACD) formally records the decisions reached during ACP by an adult with capacity5,6 and it is a legally binding document in the Australian state of New South Wales (NSW)7.

ACP, and its formal record in an ACD, is of vital importance for the communication of a person’s wishes surrounding their death to the healthcare system and healthcare workers1. Although there are no statutory ACDs in NSW, common law states that clear unambiguous details within an ACD made by a capable adult about treatment that person does not wish to receive must be respected if applicable to the medical situation at hand2.

ACP is particularly relevant to the increasing ageing Australian population, with over one-third of acute admissions and half of the total number of bed days estimated to be taken by those aged over 65 years by 20501. ACP has been shown to reduce hospital admissions and treatment performed under the premise of medical interventionism, and to facilitate access to palliative care8-11. This emphasises the necessity for organisations such as aged care service providers to encourage the uptake of ACP/ACDs among their clients, as a time of acute care is not the optimal time for such discussions1. By better understanding the current facilitators and barriers surrounding ACP, improvements can be made to foster an increase in uptake of ACDs.

Research surrounding ACP in Australia is still evolving12,13 but current evidence suggests that uptake of ACP and ACDs among healthcare workers in rural Australia is low13,14, which is concerning for older people living in these areas as ACP plays an important role in end-of-life care. Previous Australian research has explored the perspectives and attitudes of general practitioners (GPs) and nurses to ACP15,16 but, to the authors’ knowledge, the perspectives of healthcare workers in residential aged care facilities (RACFs) have not been comprehensively examined, particularly in western NSW where the present study is situated. The present mixed-methods study therefore sought to provide a current perspective on the attitudes and practices of healthcare workers from RACFs towards ACP and ACDs in western NSW. A secondary aim was to examine the influence of experience in aged care on attitudes and practices.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey of current practices and attitudes towards ACP was conducted among healthcare workers of private RACFs in the central west, far west and Orana regions of NSW between July and November 2016. Fifty-six eligible RACFs were identified from the Department of Health’s NSW aged care service list17.

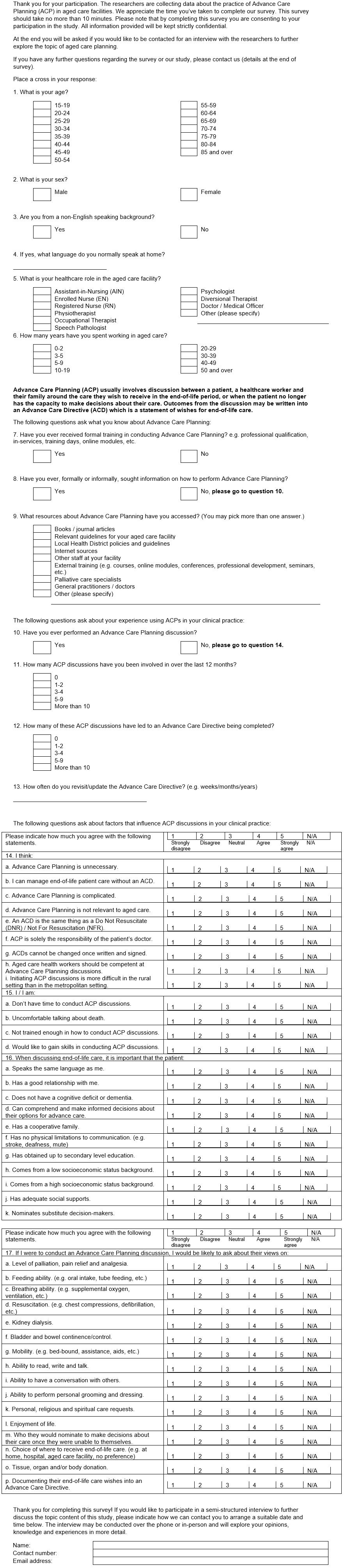

A questionnaire in English was developed (Appendix A) by the researchers, drawing on published ACP documents18 and informed by previously published surveys in the area19,20. The survey tool was designed to delve in more depth into the perspectives and attitudes of healthcare workers than previously published tools have done. Demographic information, as well as details regarding experience in aged care and ACP, were primarily collected through use of closed-end questions. Five-point Likert-type scales were used to collect information about respondents’ knowledge, patient factors, personal factors and communication regarding ACP. A focus group of two nursing staff pilot tested the survey and their recommendations were incorporated into the final version before it was distributed.

Hard copies of surveys, complete with participant information sheet and reply-paid envelopes, were mailed to RACFs following an initial contact call to 56 eligible RACFs17 to gain their consent and an estimate of staff numbers.

Inclusion criteria were professional healthcare staff (including but not limited to nurses, doctors and allied health professionals) of private RACFs in the study region. Respondents in roles not professionally involved with the care of residents in the facility were excluded from the study, including carers.

Survey data were de-identified prior to entry into a Microsoft Excel 2016 database for descriptive analyses. Chi-square tests, or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate, were used to examine the relationship between experience, information seeking regarding ACP and participation in ACP discussions. A Mann–Whitney U-test was performed with the subgroups of those with less than 5 years of experience and those with greater than 5 years of experience working in aged care to compare their perspectives and attitudes towards ACP. Statistical analyses were performed, using SPSS Statistics v22 (IBM, https://www.ibm.com/au-en/marketplace/spss-statistics), with a p-value of <0.05 considered to be significant.

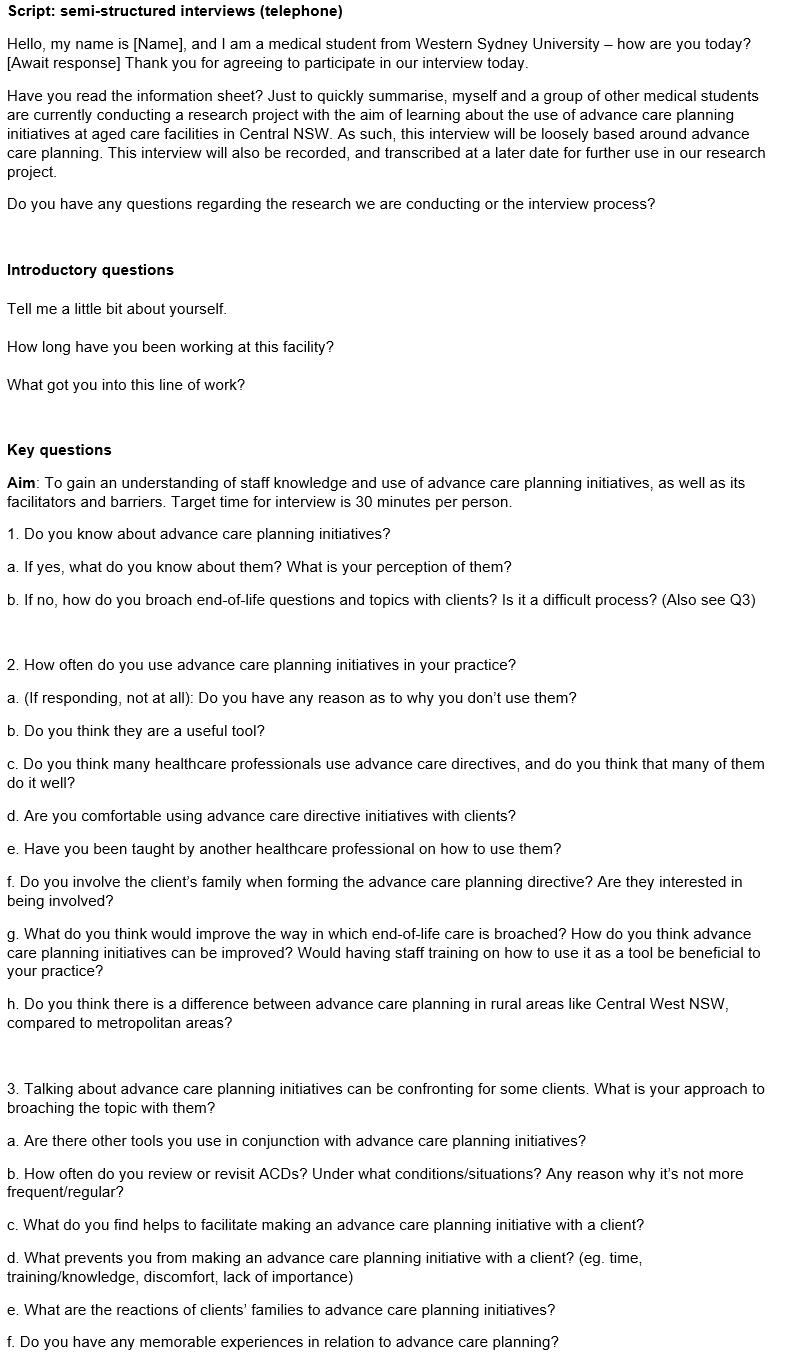

Survey participants could elect to provide their contact details for participation in a semi-structured interview that further explored their perceived barriers and enablers to ACP. Questions used to guide the interviews were derived from topics in the survey and review of the literature (Appendix B). Purposive sampling was used to select interview participants with different roles and durations of work in aged care. Written informed consent was obtained from all prospective participants prior to conducting the interview. To ensure consistency, interviews were conducted via telephone by one investigator (AA) and recorded for transcription and analysis.

All interviews were transcribed verbatim and de-identified prior to analysis. Two investigators (LL and PB) independently analysed the transcripts using a thematic analysis approach. Coding reports were summarised and cross-checked. Where divergent interpretations occurred, further discussion and review of the qualitative data occurred until consensus on the themes and subthemes was reached.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee (approval H11327).

Results

Data presented herein represent a synthesis of the quantitative survey data and qualitative interview data.

Participants

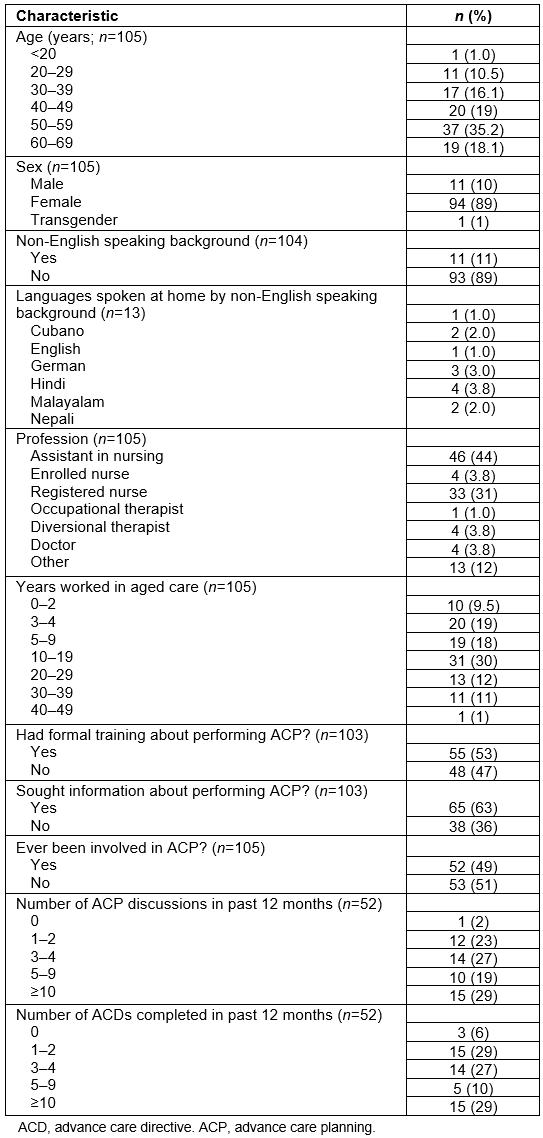

A total of 109 completed surveys from 12 RACFs were returned. Respondents spanned all age categories, with the majority (78%; 82/105) aged between 35 and 64 years (Table 1). Just over half (54%; 56/105) have spent greater than 10 years working in aged care and the majority of respondents were nurses (79%; 83/105).

With regards to personal experience with ACP and ACDs, 49% (52/105) had been involved with ACPs at some point in their career. Of those, 48% (25/52) and 38% (20/52) had completed five or more ACP discussions and ACDs in the previous 12 months, respectively. 53% of all respondents (55/103) had some form of formal ACP training, while 63% (65/103) had formally or informally sought advice about conducting ACP. Informal training from experienced staff in their facilities and formal training such as seminars were reported to be the most frequently accessed sources of advice by the survey participants.

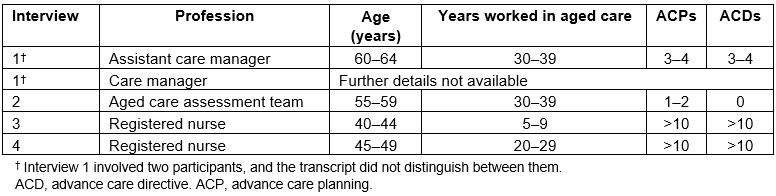

Four in-depth interviews were conducted with five participants (one interview included two participants who had made prior arrangements between themselves to be interviewed together). Demographic details of interview participants are described in Table 2.

Association between experience, training, information seeking and involvement in advance care planning

There was an association between formal training in ACP, information seeking regarding ACP and involvement in ACP. Those with formal training in ACP were significantly more likely to have sought information about ACP (Χ2=18.576; degrees of freedom (df)=1; p<0.001) and been involved in ACP (X2=7.147; df=1; p=0.008).

Years of experience was dichotomised into less than 5 years of experience and 5 years or more for the purposes of analysis. Those with 5 years or more experience were more likely to have participated in ACP than those with less than 5 years of experience (X2=4.685; df=1; p=0.030). The same association was not observed between years of experience and formal training in ACP (X2=0.354; df=1; p=0.552) or seeking information regarding ACP (X2=0.723; df=1; p=0.395).

Table 1: Demographics and personal experiences with advance care planning and advance care directives of survey respondents (n=109) working in residential aged care facilities in western NSW

Table 2: Characteristics of interview participants (n=5)

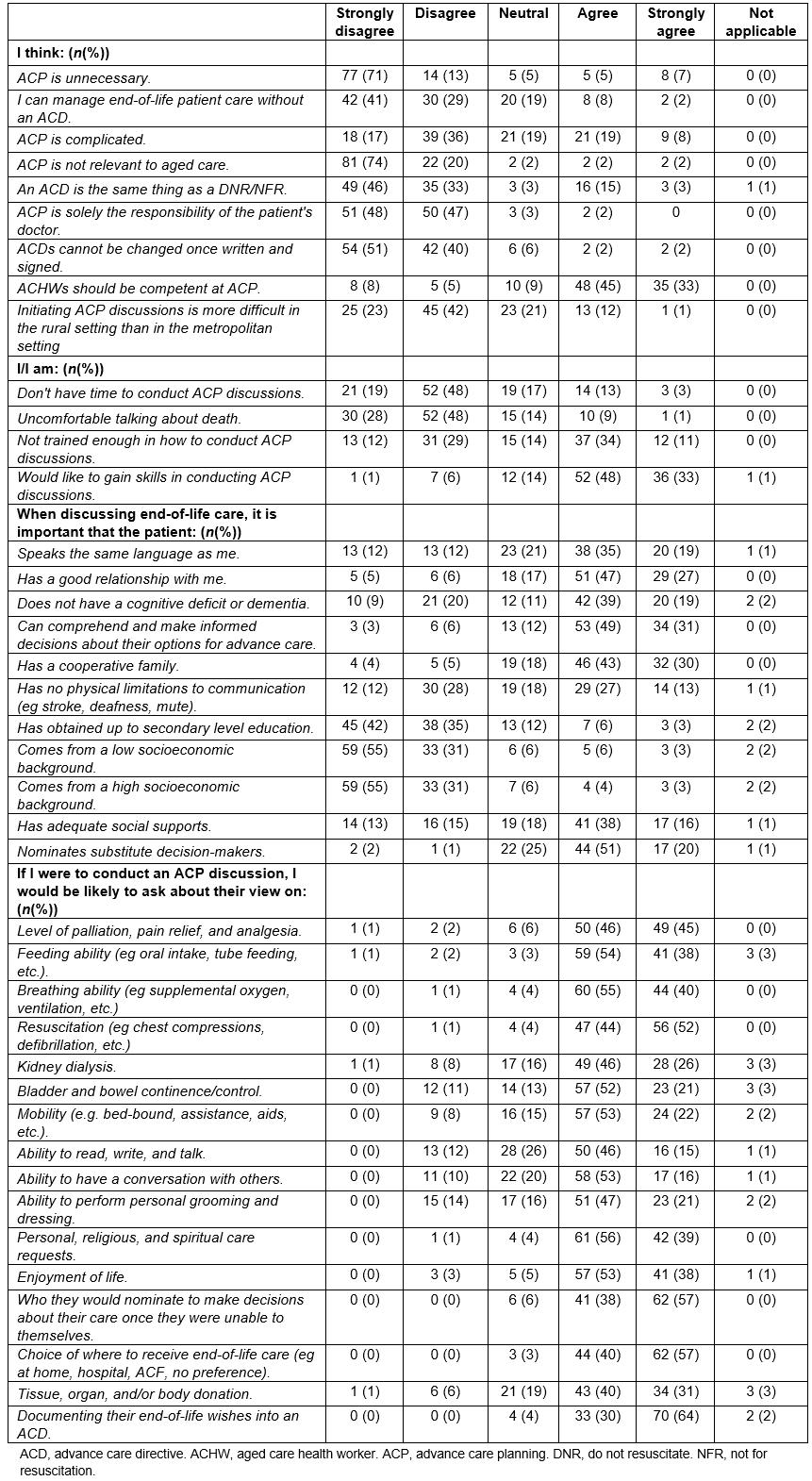

Table 3: Assessing attitudes and practices regarding advance care planning in residential aged care facilities in western NSW

Utility and uptake

Respondents recognised the importance of ACP in RACFs (Table 3), with the majority strongly disagreeing with the statements ‘ACP is unnecessary’ (71%; 77/109) and ‘ACP is not relevant to aged care’ (74%; 81/109). Most respondents understood that there was more to an ACD than just being a ‘do not resuscitate’ (or ‘not for resuscitation’) order (79%; 84/107) and that they can be revised as the situation changes (91%; 96/106).

Almost three-quarters of respondents (70%; 72/103) indicated that end-of-life care of patients is more manageable for them when an ACD is in place. Most indicated that they thought ACP was a responsibility of all aged care health workers, who should be competent in the practice. Just over half of participants disagreed with the statement that ACP was complicated (53%; 57/108) and when asked about the rural setting making ACP more difficult, 65% (70/107) of respondents disagreed that it was an issue.

Overall, the majority of respondents were comfortable talking about death (76%; 82/108) and thought that they did have enough time to conduct ACP discussions in the workplace (68%; 73/108). Regarding the statement ‘I am not trained enough in how to conduct ACP discussions’, respondents were relatively evenly split, with 45% (49/108) responding in the affirmative and 41% (44/108) responding in the negative to this statement. Despite this difference, most respondents (81%; 88/109) said they would like to further their skills in conducting ACP discussions.

Most agreed (76%; 21/27) that ACDs should be revisited every 12 months. All interviewees thought that they should be revisited when the patient’s clinical condition deteriorates or new information arises.

I don’t think we’d really have time to be revisiting them more often than annually. If there’s ... a rapid decline in the person’s condition, we would revisit that again with their appointed power of attorney. (Interview 1)

The utility of ACDs lies in their pre-emptive nature of addressing uncomfortable questions and scenarios while the patient is of full mental capacity and time is available for comprehensive discussions. Almost all survey respondents (94%; 103/109) agreed that they would raise the issue of substitute decision-makers with patients, with most (62/87; 71%) feeling that it is important for substitute decision-makers to be nominated during end-of-life discussions. In the absence of ACP these questions may not be answered confidently by family, particularly when the patient is rapidly deteriorating. This issue of unnecessary resuscitation was emphasised in the interviews as a highly distressing situation that ACP can help prevent.

Before [ACDs became routine at our organisation], we had a little lady that only came in for respite ... she arrested and we had no advance care planning ... so we had to try and resuscitate. The family all turned up ... one person was saying ‘keep going’ and the other person was saying ‘no, stop’ and it was not pleasant for anybody involved. (Interview 3)

Having a good relationship with the patient was seen by survey respondents (73%; 80/109) as an important factor in ACP. A cooperative family was another important factor supporting effective ACP (73%; 78/106). However, it should be noted that not all survey participants (9/109; 8%) believed that it was important for the patient to comprehend and make informed decisions about their end-of-life care options during ACP discussions.

There has been a trend in recent years towards ACDs being completed proactively by RACF staff at earlier stages in residents’ care, even if they are unlikely to be candidates for end-of-life care in the near future.

Initially [ACP was] something that we always avoided. Let’s get them into care before we talk about it because it will scare them off, but now we’re all more comfortable with the whole idea. (Interview 2)

The removal of the distinction between low- and high-level Australian RACFs has led to the wider implementation of ACP discussions underpinned by support from local health districts and primary health networks.

[Ten years ago] we were only low-level care ... but since that time we’ve adopted aging-in-place and so now they stay here and pass away and have terminal palliative care. (Interview 2)

Roles and responsibilities

Implementing ACPs in RACFs requires a framework in which healthcare workers understand each other’s roles, and the responsibility is shared and delegated. ACP discussions were frequently initiated by experienced registered nurses and not necessarily with a doctor.

I notice more often now the nurses are doing it and explaining it all and then the doctor’s just signing off on it at a later date ... I think it probably gets more complicated with terminally ill patients ... the oncologists, the GP and the palliative care nurses work together quite well. (Interview 2)

Almost all survey respondents (95%; 101/106) disagreed with the statement that ‘ACP is solely the responsibility of the doctor’. While GP input was necessary to medically clear management plans made in the ACD, the practical extent depended both on the GP and the complexity of the patient’s situation. To support management of complicated patients, interviewees described use of local palliative care teams when available, including specialist nurses, physicians, and often oncologists.

While only half of survey respondents (53%; 55/103) had received formal training, over three-quarters (78%; 83/106) believed that aged care health workers should be competent at ACP discussions. When presented with the statement ‘I am not trained enough in how to conduct ACP discussions’, the survey responses were equivocal with 41% (44/108) expressing disagreement, 14% (15/108) neutral and 45% (49/108) agreeing. Further examination of participant ratings for this question and their self-reported participation in ACP discussions in the previous 12 months (dichotomised to <10 discussions or ≥10 discussions), however, did not show any significant association between the two variables (p=0.284, Fisher’s exact test). This reflects differing levels of self-perceived ability at conducting ACP. Interview participants emphasised the practice of ACP discussions as a process of continual improvement. Subjective ability in ACP performance is implied to increase with time and number of discussions completed. As such, experienced team members tended to perform the majority of ACP. Openness to further training and upskilling in ACP was common among participants (88/109 survey responses; 81%).

The palliative care nurse specialist from Primary Health gives education sessions to the staff regarding advance care planning every two months. (Interview 1)

I think some of us nurses that aren’t in the palliative care stream probably need to be a little bit more educated and proactive ... You’re nervous when you’re doing it, but if you learn properly, you’re confident that you know what you’re talking about. (Interview 1)

Influence of experience on perspectives and attitudes to advance care planning

A subgroup analysis was conducted with two groups: those with less than 5 years of experience working in a RACF, and those with 5 years or more. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups when examining their responses related to their views on the positive role of ACDs, the level of intervention acceptable, level of functioning to be maintained, and the need to inquire about specific requests with end-of-life care (data not shown).

The rural experience

The rural context has inherent attributes that influence the performance of ACP and ACDs, particularly in the environment of RACFs. The majority of survey respondents (65%; 70/107) did not think that initiating ACP discussions was more difficult in a rural setting. Rural healthcare workers may experience a sense of familiarity with patients that facilitates these conversations, as the interview participants noted that patients and families are more likely to be known to staff in their communities and that this established rapport eases the end-of-life discussion.

I’ve looked after these people when I’ve worked in the community ...I already have a good rapport so there’s no barrier to getting their advance care plans completed. They’re quite open to discuss it. (Interview 1)

The sense of community greatly facilitates the process of ACP as healthcare workers become personally invested and may devote extra time and attention to patients’ end-of-life care, ultimately enriching the experience for all involved.

I find it very easy to deal with doctors out [rurally]. As soon as we need them, they come. It doesn’t matter what time of day it is or anything else. (Interview 3)

About two-thirds of survey respondents (68%; 73/108) disagreed that they ‘did not have enough time to conduct ACP discussions’. Despite acknowledging resource limitations, it seems that meeting patient needs through ACP is not left wanting.

I was at the time the only registered nurse there [that could discuss ACDs] ... we’ve just had another R.N. start about eight months ago. (Interview 3)

There was one poor guy doing all the palliation and they’ve recently proved that there was enough patients for two people ... I think we do a really good job with our limited resources out here, but there’s room for more education and ... doctors that are interested in palliative care. (Interview 2)

Discussion

The present mixed-methods study sought to provide a current perspective on the attitudes and practices of healthcare workers from RACFs towards ACP and ACDs in western NSW.

The findings support that healthcare workers endorse the implementation of ACP and recognise its benefit for the continuing care of patients in RACFs. Almost half of the participants reported having been involved in ACP at some point. Of these, most had conducted three or more ACP discussions in the previous 12 months and all but three had completed one or more ACDs in the previous 12 months. This contrasts with evidence suggesting ACP interest and ACD performance among healthcare workers in rural Australia are low13,14 and is encouraging given the commitment from various levels of government to further the ubiquity of ACDs in healthcare through clinical guidelines, state action plans and a national policy framework1,21,22. The shifting landscape of aged care service delivery, including the removal of low- and high-level care categories23, alongside attitudes generally favouring early ACP, is also likely contributing to the subjective increase of ACD uptake in western NSW. Years of experience in the aged care setting was not associated with general attitudes and practice of ACP in this study, suggesting that there is agreement in priorities for end-of-life care irrespective of experience and this may be influenced by both formal and informal training. Future research could explore this in more detail.

The possibility of recent increases in ACD uptake being partially attributed to the removal of distinction between low- and high-level Australian RACFs was explored in the interviews. Where before some low-level care facilities did not engage in ACP, this structural change has led to the wider implementation of ACP discussions underpinned by support from local health districts and primary health networks.

While there is evidence of increasing ACP uptake within the studied population, the use of ACP should be implemented with due caution. It has been recommended by bodies such as the Australian Law Reform Commission that the appointment of a substitute decision-maker can be important but should not be a condition of receipt of aged care, and that measures to prevent elder abuse and undue influence, such as ensuring the person has testamentary capacity, should be implemented24.

This study highlights the important role that healthcare workers other than doctors can play in the delivery of ACP in western NSW. Although published guidelines reinforce a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to ACP21, it has been suggested that this model of care delivery is lacking clear roles and can be a barrier to the ACP process13. In western NSW, nurses appear to lead the way in ACP, involving doctors and other professionals as needed, such as in complex chronic and palliative care streams. A nurse-led model of ACP has been promoted before25,26. RACF nurses are well suited to perform ACP due to their exposure to patients requiring end-of-life planning. Empowering nurses with further training and support would likely provide enhanced coordinated care to patients, reducing the burden on rural doctors who themselves face several personal barriers to conducting ACP well among their patients15,27.

Level of training can either be a facilitator or barrier to ACP/ACDs. The present study’s findings suggest there are disproportionate numbers between staff who have received formal ACP training (approximately half of respondents) and the large majority, who believe all aged care staff should be competent at performing these discussions. This disconnect reiterates the role of upskilling in building the confidence of the rural workforce, an identified issue among GPs and nursing professionals15,19,25,28. Informal training and advice in ACP is also carried out by more experienced nurses and local palliative care teams in western NSW. Given staff are receptive, the authors conclude there is a role for the increased provision of formal training from bodies within the healthcare system. Rhee, Zwar and Kemp15 suggest that interventions to improve attitudes and skills in ACP should be system-wide, resulting in the development of formalised structures to communicate and implement ACDs where completed. These interventions should also align with recommendations from government legal bodies, such as those addressing potential elder abuse 24. Systematic change is only achievable when the healthcare workers involved can be brought aboard.

Within the studied rural RACFs, the perceived reduced number of staff available to provide appropriate care and subsequent time constraints were acknowledged as a barrier26. This may reflect the steadily declining number of nurses working in aged care in Australia. Between 2003 and 2016, the number of registered nurses decreased from 21% to 15% of the aged care workforce29. Perceived staff deficits can make management of ACP discussions cumbersome, particularly during times of administrative change. Surprisingly, further interview analysis suggested that factors including support from available local healthcare bodies such as palliative care teams, primary health networks and the local health district are able to counteract problems stemming from such issues. Interview data demonstrated that professionals in these settings were both more resourceful and willing to invest their personal time and effort into continuing care for residents, further alleviating the aforementioned barrier.

The authors hypothesised that the rural setting would confer limited resources to the delivery of ACP30. However, working in a RACF within western NSW was uniformly identified through the interviews to be a strong enabler in initiating ACP discussions, as it was synonymous with working in a supportive community where subsequent care plans were handled with considerable care. This was also seen in a positive light when overcoming cultural barriers to conducting comprehensive ACP discussions. For example, it was acknowledged in the qualitative arm of results that some patients were originally uncomfortable with conversations dealing with death30,31. This was offset by several facilitating factors such as improved rapport and substantial community support when the patient and their family are known to the healthcare worker within the small community. There was little to suggest that this cohesive environment was absent from metropolitan facilities; however, many of those interviewed had little-to-no experience working in such settings.

The authors postulated that some barriers to ACP would be related to communication issues. Those identified included diminished capacity to make informed decisions due to dementia4, and the lack of a supportive family. Such barriers were reportedly mitigated through the early implementation of ACP, often before the resident was admitted into the RACF or before significant functional decline. However, situations in which people lack the legal capacity required to begin the ACP process or to revise a previously completed ACD are not uncommon, and these cases were unfortunately not addressed in this study’s results. Blake, Doray and Sinclair32 have explored several challenges surrounding ACP in the context of dementia, and have particularly recommended that adopting collaborative negotiation for a ‘most agreeable outcome’ may be more appropriate when making treatment decisions for these patients32.

Strengths and limitations

The majority of this study’s population were female (89%) and aged 30 years or more (88%). This correlates well with existing data on the RACF workforce, which suggests that 80.5% of workers are aged 35–64 years and 89.5% are women33. However, as several large facilities declined to provide consent or failed to return posted surveys (12 out of 56 RACFs participated – organisational participation rate 21%), the study population and this study’s results may not be entirely representative of the central west, far west and Orana regions’ RACFs. In addition, there was an under-representation of doctors in the study and so this data may not be representative of the perspectives of doctors within the studied region. It is also possible that the method of recruiting survey and interview participants tended towards those with a more positive perspective and/or experiences with ACP and ACDs.

As the studied region is relatively culturally homogenous, results may not be generalisable to a metropolitan area containing a wider variety of cultural backgrounds, religions and languages spoken.

Conclusions

ACP plays a critical role in aged care and end-of-life care, and several factors influence its implementation into RACFs in western NSW. There is a consensus that ACDs are important and will only become increasingly so given Australia’s ageing population. Healthcare workers find that ACDs provide a large benefit in optimising care for their patients. The present research also shows that, within the central west and Orana regions, ACDs are approached in a multidisciplinary fashion with responsibility shared among multiple practitioners, and that a patient’s ability to communicate effectively is conducive to the facilitation of an ACD. Current healthcare workers are desirous of more training, but acknowledge that on-the-ground experience may be more beneficial.