Introduction

Abortion has been legal in Victoria, Australia, since 2008 (Abortion Law Reform Act 2008 (Vic)) and medical termination of pregnancy (MTOP) has been available in Australia since 2012. These two developments were expected to improve access to abortion for women facing unintended pregnancy, yet decriminalisation has so far not resulted in improving access to services in Victoria or reducing stigma1, and uptake of MTOP has been slow2. It has been estimated that in 2017 there were 12.2 terminations per 1000 women aged 15–44 years in Victoria3, and that during 2014–2016 there were 65 451 abortions with operating room procedure conducted in Victoria4. Similar figures are not available nationally, nor has data been aggregated by metropolitan versus regional and rural areas.

Especially in rural areas, general practitioners (GPs) are often the first point of access when women experience unintended pregnancy and play a key role in facilitating access to appropriate services. This article uses one of the five regions of regional and rural Victoria as a case study to examine GPs’ knowledge and practice in relation to unintended pregnancy and referral for pregnancy-options counselling and abortion. The research explores access to services from the perspective of rural and regional GPs.

The Grampians region spans from western Victoria to the border of the state of South Australia, and includes the major regional centre of Ballarat, which has a population of 100 283. This research focused on seven local government areas in the Grampians region where abortion services are known to be limited. These were areas of relative disadvantage and have a high rate of teen pregnancy5. The precise location where this research was conducted is not reported in this article, to protect the identities of research participants. The total population of the areas researched, as of 2014, was 54 372. All demographic information was obtained from the Department of Health and Human Services Victoria website in 2017.

Research consistently shows that rural women face greater difficulties than their urban counterparts in accessing abortion services both in Australia6 and in other developed countries7,8. MTOP, involving the use of mifepristone and misoprostol to induce abortion, is thought to be a way to improve access to abortion for women in rural and regional areas2. Rural GPs can become prescribers by undergoing a short, online training program with MS Health (a not-for-profit pharmaceutical company under Marie Stopes International). During the data collection period of this study, organisations such as Marie Stopes and the Tabbot Foundation offered MTOP telemedicine services that women could access with support of their GPs. Evidence suggests that tele-abortion can reduce cost, facilitate earlier terminations, reduce stress, make termination of pregnancy more available overall, and is rated favourably by women9.

Rural areas in Australia experience scarcity in health services generally and rely more heavily than urban areas on a workforce of overseas-trained doctors10. Abortion is a controversial issue worldwide, and is still criminalised in many countries11. It is not known whether the reliance on overseas-trained doctors affects access to abortion services. In addition, rural areas are often thought to have a more conservative culture than urban areas12. A qualitative study with 11 professionals working in a range of areas in the Grampians region found practical barriers and negative attitudes reduced women’s access and, as well as the provision of more services, the authors suggest there is a need to normalise the use of family planning services in the area12.

Section 8 of the Abortion Law Reform Act 2008 (Vic) states that practitioners who have a conscientious objection must inform patients of their objection and refer them to a colleague who does not hold a conscientious objection. While conscientious objection can limit access13, in Victoria doctors have a legal right to abstain from providing advice about abortion to their patients, as long as they adhere to the requirement to refer the woman to a provider who does not hold a conscientious objection (Abortion Law Reform Act 2008 (Vic)). This is known in ethics as the ‘conventional compromise’14 or the ‘moderate position’15. While it is an attempt to balance the rights of the patient and the rights of the doctor, there is ongoing debate in ethics literature about the appropriateness of this position16.

This article reports on research designed to address the absence of evidence about GP knowledge and practice in relation to unintended pregnancy services in rural and regional Victoria. The aim was to describe GPs’ practices when women present to them with an unintended pregnancy, and their knowledge and opinion of the services available to support these women in the Grampians. The overall goal was to inform future health promotion and service development in the region.

Methods

This mixed methods study was designed in collaboration with an expert reference group, consisting of representatives from a local women’s health service, primary health network, primary care partnership and a number of health services. The collaboratively developed study design included a survey of GPs practising in the chosen catchment areas, and a follow-up semi-structured telephone interview. The eligible population was 84 GPs publicly listed as practising in 33 practices in the area. All were sent a letter of invitation with a paper survey, invitation to participate in an interview, and a reply-paid envelope. Two weeks later, each practice was sent an email with a link to the online version of the survey. This approach was deemed the most appropriate recruitment method, and most likely to elicit a response.

Data were collected between April and August 2017. The survey included both closed and open-ended questions. It asked participants to indicate how often they discussed the following when women presented with unintended pregnancy: pregnancy-options counselling, surgical termination of pregnancy (STOP), MTOP, tele-abortion, sexually transmissible infections and contraception. GPs were also asked how often they referred women to another provider because of a conscientious objection. An open-ended question asked GPs to detail their impression of available services to support women facing an unintended pregnancy. Six GPs indicated on their questionnaires that they were open to being interviewed, with five GPs ultimately participating in a telephone interview. The sixth GP was not available for an interview during the period of data collection. In the semi-structured telephone interviews, GPs were asked to elaborate on the questions asked in the survey: their practices when women present with an unintended pregnancy, what termination-of-pregnancy services they were aware of, what the referral pathways were, and how they thought GPs could support women better. Example questions included ‘Can you tell me the steps you would go through with a woman presenting with an unintended pregnancy?’ and ‘In your opinion, is there anything GPs could do better to help patients with an unintended pregnancy?’ The interview duration was 15–35 minutes. All were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

This was a mixed method study involving surveys and telephone interviews. The participants included GPs practising in seven local government areas in the Grampians. Interviews were conducted by one of two researchers (LK or SC). LK and SC read through all the transcripts separately and then collaboratively developed a coding framework able to capture the main themes in the data. The data were then coded and further analysis performed on coded data. Due to the sensitive nature of the research and the research context of small rural communities, special care was taken to remove identifying information from the data. Feedback and advice from the expert reference group was sought on how to interpret and present the results.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Health Sciences Human Ethics Sub-Committee of the University of Melbourne (ethics number 1748829).

Results

Survey findings

Sample: A total of 84 GPs were approached to participate, 27% (n=23) completed the survey and 6% (n=5) also agreed to participate in a semi-structured interview, which is comparable to other studies in general practice17. Twelve were female and 11 male; they were aged 27–67 years and had worked in the region for approximately 9 years (range 2 months – 30 years). Participants saw approximately three women per year with unintended pregnancy (mean=2.9), while there was one outlier who saw 25. Sixty-five percent of participants (15 of 23) received their medical training overseas. This is higher than the 47% reported for regional and rural areas in Australia10. Of these overseas-trained doctors, 10 were male and 5 were female.

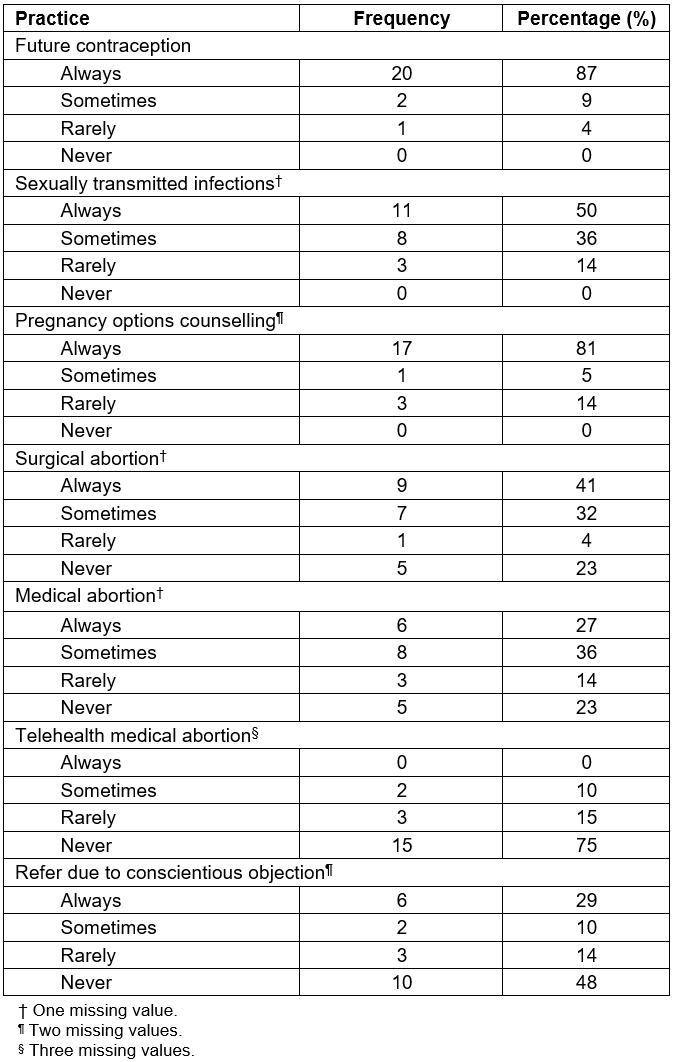

Practice when women attend with an unintended pregnancy: Table 1 shows a summary of GPs’ practices when women presented with an unintended pregnancy. Thirty-nine percent of participants ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’ referred patients to colleagues because of conscientious objection. No participant would ‘always’ discuss telehealth medical abortion, 27% would always discuss MTOP, 41% would always discuss STOP, 50% would always discuss sexually transmissible infections. Much more common practices were pregnancy-options counselling (always discussed by 81%) and future contraception (always discussed by 87%).

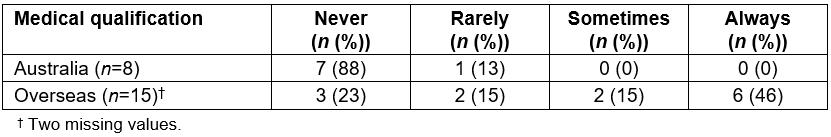

Of the eight participants who ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’ referred women on to colleagues because they held a conscientious objection, all were trained overseas. These eight participants made up 61% of the overseas-trained GPs (although there were missing data for two participants). Table 2 shows referral due to conscientious objection, by training.

The majority of survey participants who reported ‘never’ or ‘rarely’ referring women on to colleagues because of a conscientious objection said they ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’ discussed termination of pregnancy (either STOP or MTOP). This suggests that most GPs with a conscientious objection to abortion are meeting their responsibility to refer women on. However, of those who did not refer patients, two said they ‘rarely’ discussed options counselling, two ‘rarely’ discussed MTOP, and one ‘rarely’ discussed STOP. These numbers need to be interpreted with caution as the sample is small; however, of concern was a participant who reported ‘rarely’ referring women on due to conscientious objection but also ‘rarely’ discussing options counselling, STOP or MTOP.

Table 1: Reported practice of general practitioners when women present with an unintended pregnancy

Table 2: Participant referral for conscientious objection, by country of medical training

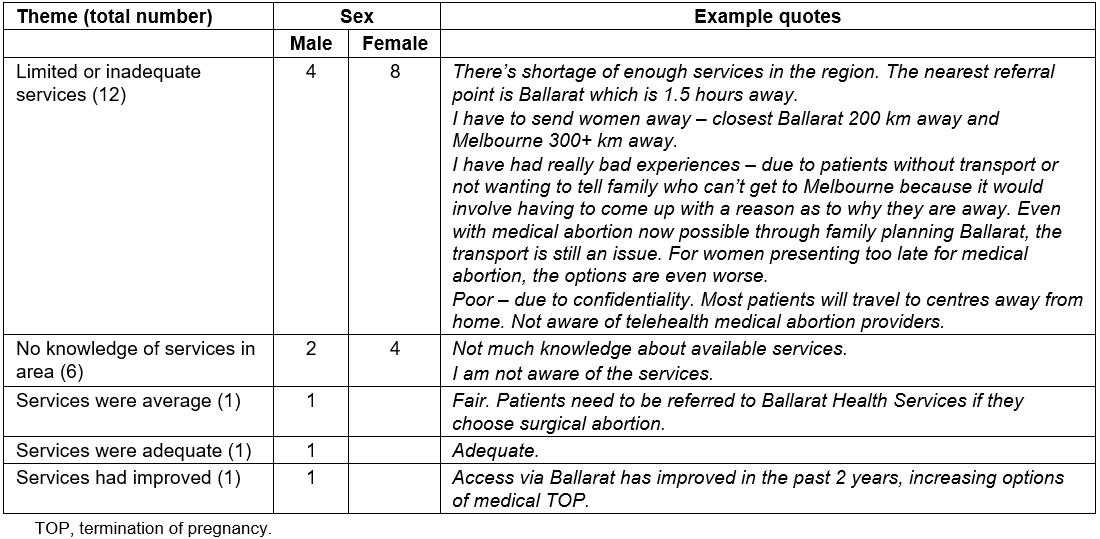

Perceived adequacy of services: Participants were asked an open-ended question about their opinion of the services for women facing an unintended pregnancy in the Grampians region. Only three survey respondents said the services in the region were adequate, average or improved. The remaining 18 participants described the services either as limited or inadequate, or claimed to have no knowledge of the services. Example quotes are provided in Table 3.

Nine participants reported referring women out of the area to either Ballarat, a regional city in the Central Highlands of the Grampians; or to Melbourne, the capital city of Victoria, for terminations. One of the survey participants described the difficulty in supporting patients presenting with unintended pregnancy when they needed to refer women out of the area. They wrote:

I have had really bad experiences – due to patients without transport or not wanting to tell family who can’t get to Melbourne because it would involve having to come up with a reason as to why they are away. Even with medical abortion now possible through family planning Ballarat, the transport is still an issue. For women presenting too late for medical abortion, the options are even worse.

Table 3: General practitioner participants' opinion of services for women with unintended pregnancy

Interview findings

Interviews were grouped according to the particular positions the GPs occupied in relation to unintended pregnancy services, in order to illuminate their particular perspective. These groups were a city doctor who ran a regular clinic in one of the smaller Grampians towns, two conscientious objectors and two GPs who had considered becoming MTOP providers.

The conscientious objectors revealed that ‘conscientious objection’ occurred in different forms. Rohan and Robert (all participant names are pseudonyms), expressed different degrees of conscientious objection. Both were Christian. Rohan referred patients on to colleagues if they requested a termination but was comfortable prescribing the morning-after pill. He said:

If somebody comes and sees you within seventy-two hours and you can prevent it, then that’s alright … Prevention is better than having an abortion.

Robert, on the other hand, while not personally comfortable with performing terminations, had no objection to referring women to services where they could be obtained. Robert saw many patients for sexual and reproductive health and described himself as ‘the first port of call for a lot of women’ with unintended pregnancy. He did not ‘lose sleep’ over referring women to an abortion service and was extensively involved in the woman’s care up to the point of referral:

I do a scan … to see how many weeks they are, which sort of leads to which direction [STOP or MTOP] … Unless people are very clear in their own mind that they want a termination, I usually like to see them a second time to talk it through.

Two of the GPs interviewed, Jennifer and Julie, had considered becoming MTOP prescribers. Jennifer was new to the region and, at the time of interview, had referred her first patient for termination. Julie noted that while she was keen to become a prescriber, support from other services was needed:

… when we saw this patient, there wasn’t any feasibility that she could get an ultrasound locally for a couple of weeks … we were going to have to send her to Ballarat anyway, so it kind of defeats the purpose.

Julie, who had almost 30 years’ experience in the region, faced a similar difficulty when she considered learning about MTOP. A requirement for MTOP is having surgical backup available in case of MTOP failure:

I did ask [the] obstetrician, gynaecologist who is here in [our town] whether [they’d] be happy if I learnt about RU486 [MTOP], would [they] be my back up and the answer was ‘no. I’m not doing it’.

Thus, despite these GPs’ willingness to become providers to improve rural women’s access to terminations, rurality presented other restrictions that made it difficult for them to do so. Lisa, the city doctor working in a smaller town, added further perspective on the limitations of tele-abortion services in towns with one or two GPs. In her experience:

Rural women don’t like to go where people know them. So, they’ll often be happy to travel to Ballarat or Melbourne for a termination. These women travel anywhere, anytime. They don't think twice about it.

Her perspective was that concerns about confidentiality would trump concerns about convenience and travel. Thus, even if local GPs in these small towns were to become abortion providers, or if they were aware of the availability of tele-abortion services, Lisa’s perception was that the likelihood that women would use these services was small.

Discussion

The findings from this mixed method case study reveal several concerns from the perspective of GPs working in the Grampians region. A clear majority of GPs described the services as limited or inadequate, while some GPs said they were unaware of services. Given these GPs saw on average three women per year with an unintended pregnancy, the lack of adequate referral options is concerning.

This study found that a higher than average proportion of GPs in the region were trained overseas (from a range of countries, including in Asia, Africa and the Middle East). Within the group of GPs who were trained overseas, very high rates of conscientious objection to abortion (65%) were found. This is higher than the only available estimated rate of conscientious objection among doctors in Australia, of 15%17. A significant concern is the two participants who neither referred women nor discussed MTOP or STOP. It is possible that these two doctors hold a conscientious objection, but did not refer women to a colleague (an obligation that is enshrined in law in Victoria). Many of the countries in which these doctors were trained are likely to have restrictive abortion laws and/or policies that do not support women’s access (although this is not true for all countries in which GPs were trained). It is not known how GPs trained overseas become accustomed to different laws and practices, nor the best methods for achieving accurate knowledge and acceptance of abortion law for overseas-trained doctors. On the basis of these findings, it is imperative that further research at a national level is conducted to determine the extent of conscientious objection, and to work with stakeholders to ensure the law is understood and abided by in all settings.

Knowledge of the option of MTOP and tele-abortion, which has been favourably evaluated by women and providers, was inconsistent and only two of the interview participants discussed having offered it to women. Very few participants in the survey regularly discussed tele-abortion with women. In addition, even those who had discussed the option with women were often not able to use it due to lack of ultrasound facilities. It is likely that the promise of tele-abortion is far from fulfilled in the Grampians region and possibly in other rural areas in Victoria. There is an opportunity to offer local training and increased opportunities for doctors and nurses to upskill in these areas in the Grampians and other similar geographic areas.

This research is limited by the sample size for both the survey and the interviews. While the response rate was only 27%, this is equivalent to similar surveys with health professionals17. Ideally, further work will need to be conducted with hospital staff, gynaecologists and pharmacists, who did not form part of the population of interest for this study. In addition, saturation was not reached for the interview component of the study, so there are likely to be issues and attitudes present in the population that are not reported in this study.

Conclusion

Overall, there is a need to improve knowledge, services and adherence to legal and professional obligations in relation to termination of pregnancy, and there are clear opportunities to achieve this, with all interview participants expressing strong support for the prevention of unintended pregnancy, and many highlighting the need for good support for women up until the point of termination. Training, education and further and wider stakeholder engagement will all offer pathways to increase awareness and services for women.

Acknowledgements

This study was designed in collaboration with a project reference group comprising staff from the following organisations: East Grampians Health Service, Grampians Community Health, Grampians Pyrenees Primary Care Partnership, Stawell Regional Health, Western Victoria Primary Health Network and Wimmera Health Care Group. The members of the reference group also critically reviewed the results of the study. The authors thank the reference group members for their invaluable contributions to the research.

References

You might also be interested in:

2008 - Alcohol harm and cost at a community level: data from police and health