Trachoma Elimination Program

The program commenced in 2012 and focused on adding value to the Australian Government’s efforts to eliminate trachoma. The program aimed to increase the number of Aboriginal people being screened and treated for trachoma. It was based on the premise that community engagement is central to the elimination of trachoma1. The program employed and supported local Aboriginal community-based workers (CBWs), and residents living in remote communities, to provide a bridge between external medical and health promotion services and community members. During implementation, the Indigenous Australia Program (IAP) required evaluation expertise to assist with learning from project implementation, sourcing relevant literature and identifying improvements.

Evaluation and ways of working

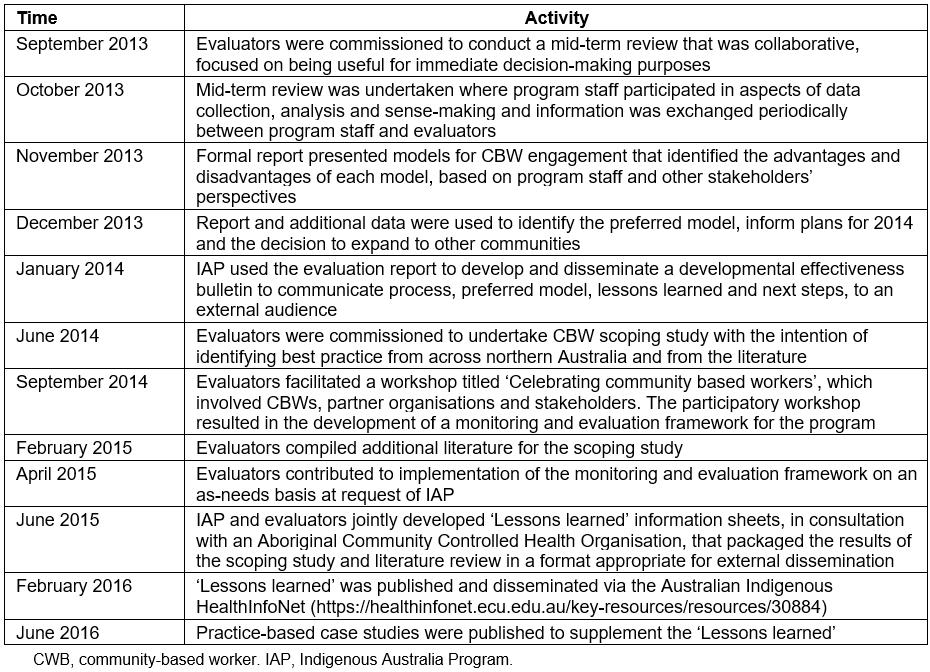

Between 2013 and 2016, IAP commissioned the external evaluators Pandanus Evaluation for approximately 10 days each year to provide evaluation expertise. There was flexibility in the contract to enable the evaluators to be responsive to the knowledge demands of IAP as they arose. A daily rate was negotiated that could be broken down into smaller segments of part days. Travel and expenses were allocated but may or may not have been used depending on the demands for travel to the field versus desk-based activities. The contract allowed for the evaluators to submit an invoice when the work was completed, which suited the unpredictable demands of IAP’s knowledge needs. Initially in 2013, IAP did not intend to commission the evaluators over a 3-year period, but the quality and timeliness of the utilisation-focused evaluation information resulted in the contract being re-negotiated annually, informed by a developmental evaluation approach across the duration of implementation2,3. Table 1 summarises types of engagement with evaluators and flow of information.

IAP was explicit in its intentions to use the evaluation to learn about what was working well and what was not, and to make decisions about program modifications based on the available findings, discussions and strategic advice from the evaluators. This ‘learning though evaluation’ framed how the evaluators reported to the program managers and staff. IAP and the evaluators agreed that providing regular briefings about achievements, issues and challenges as they were identified would provide the opportunity to discuss what was happening. This way of working is consistent with a ‘developmental evaluation approach’, where evaluation participants apply evaluative thinking to interventions that are developing as they are implemented3.

The evaluators presented findings, based on a combination of focused discussions and formal interviews with stakeholders and informants, observations during site visits and document and literature reviews, to the IAP team periodically, either verbally or by written report, at mutually agreed points in time. IAP would request additional information to clarify issues raised. They also provided opportunities to discuss options to address what was not working well and strategies that could add value. This process facilitated the application of evaluative thinking and lessons learned to the ongoing planning process. Through the process, the next steps in the evaluation would be identified or planned steps confirmed. Evaluators also provided confidential briefings, verbally and written, to the team leader if they thought it prudent. There were no ‘surprises’ when more formal reports were presented. The evaluators also facilitated participatory ways of developing a monitoring and evaluation framework with IAP, stakeholders and CBWs, and various data collection and ‘sense making’ workshops.

The processes were also in line with the knowledge translation approach, described as ‘A dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically-sound application of knowledge to improve [health]’4.The evaluators synthesised existing knowledge from the literature with the emerging findings. This process was participatory, engaging key stakeholders from the beginning, with the evaluators acting as a knowledge broker and responding to knowledge needs from both groups over a long period of time5. These processes can also be described as a form of ‘integrated knowledge translation’, which allows a co-production of knowledge through integrating different stakeholders’ knowledge bases, creating a ‘sustained synergy’ (p. 33), and facilitating a collective approach to solve problems6. In this way, the translation of evaluation findings, alongside research and other forms of data analysis, occurs in an ongoing, sustained way.

Table 1: Timeline summarising types of engagement with evaluators and flow of information

Lessons learned

1. Combining external information and practice-based knowledge with local knowledge and experience is invaluable

IAP’s strengths were in understanding the immediate implementation setting and the target audience for the evaluative information. However, the external evaluators were able to report on the views of the CBWs, health service staff and stakeholders about how the CBW component could be strengthened. The flexible contract arrangement enabled IAP to be able to ask for answers to specific information needs as required. IAP, knowing the target audience requirements, ensured that the information sourced by the evaluators in a timely manner was packaged in a way that suited the audience. The amount of work required to achieve the ultimate product was substantial on both sides but the information was what was needed, at the right time and in an appropriate format.

2. It is useful to incorporate evaluative information from inception and for the duration

IAP found value in having relevant and timely information about the strengths and weaknesses of the models of service delivery to assist in preparing for discussions internally with management, communicating to senior executives and the board, and sharing successes and lessons learned externally with donors and stakeholders. Having access to critical friends who could share the day-to-day achievements and frustrations, be a sounding board to test ideas and engage with others who had a long-term, big-picture perspective was of great benefit to the IAP. The value of informal interactions and engagement should not be underestimated as a legitimate source of evaluative thinking applied at exactly the right time.

For the evaluators, receiving feedback that the information being provided was useful meant that effort could be focused on refining the results and answering any remaining questions. Because of the in-depth discussions between program staff and the evaluators prior to the provision of formal pieces of work, no additional time was required and the terms of the consultancy were satisfactorily met. No time was wasted wondering if they were on the ‘right track’ because the collaborative approach meant there was constant assurance that we were all on the ‘same track’.

3. A collaborative working relationship can result in higher quality information being produced

Value for the evaluators came in the form of being able to engage with the CBWs through participatory approaches to ensure their insights could be incorporated into the mix of information obtained. This information could only be secured because of the existing relationships that the IAP had with the community members and the introductions that were made. Involving community in the co-design of the monitoring and evaluation framework was essential to ensure a meaningful yet rigorous document that would be useful in the long term.

However, for community members the distance between evaluative knowledge and benefits for their communities was understandably a stretch. Improvements in the program ‘down the track’ can seem intangible for community members wanting to see immediate positive change. IAP attempted to bridge this gap by making the link between involvement with the evaluators and a tangible benefit connected to the actual program a priority.

An example was calling the workshop to develop the monitoring and evaluation framework ‘Celebrating community based workers’. This title ensured that all participants understood that there was not only a focus on evaluation but also an emphasis on learning, celebrating success and sharing stories between communities, and it resulted in practical information being immediately accessible for the people who needed it the most.

IAP aims to ensure that evaluation activities are undertaken with the appropriate respect for, and participation of, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals and communities with a focus on reciprocal respect, cultural humility and appropriate acknowledgement7. Hence, using a collaborative approach not only resulted in higher quality information being produced but was consistent with a culturally appropriate way of incorporating evaluation expertise.

4. It is important to communicate findings to different audiences in different formats

Evaluators found frequent, short telephone conversations, face-to-face briefings and facilitated discussions to be effective and efficient ways of reporting findings during the course of the evaluation, providing an opportunity for clarification and facilitating ‘learning along the way’. The workshop and facilitated discussions that brought together key stakeholders enabled everyone to hear the same information and discuss it as a group.

Written reports, development effectiveness bulletins and information sheets were targeted to different groups and served specific purposes. As information came to hand, IAP made this information more widely available to an external audience. The information was packaged in ‘Lessons learned’ information sheets that formed part of a wider knowledge translation project8.

Conclusion

As a result of the evaluation, IAP arrived at a clearer understanding of the potential and importance of evaluation. The evaluation elicited information that could be used immediately for learning and improvement, as well as for sharing with stakeholders and others, in appropriate formats. The trusting relationship that developed between IAP and the evaluators during the consultancy led to an openness and willingness to use evaluative thinking when considering what was happening in the program. IAP realised that there was no blame to be apportioned when it was discovered that some aspects of the program were not going so well. Issues could be rectified after they were identified, and strengths celebrated. The lessons learned from the evaluation may be helpful to other organisations and program managers, and encourage them to undertake a utilisation-focused evaluation, using a developmental approach for learning and program improvement.

References

You might also be interested in:

2008 - Sharing after hours care in a rural New Zealand community - a service utilization survey