full article:

Introduction

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals constitute a minority of the US population, spanning all ages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, geographic regions, religious affiliations, and socioeconomic strata1. Recent studies have documented poorer physical and mental health outcomes among LGBT persons compared to their heterosexual and cisgender counterparts2,3. These trends have prompted calls to prioritize the LGBT community in future research in way that that extends beyond just sexual health issues4,5. Improving the overall health, safety, and wellbeing of LGBT individuals in the USA through both research and practice is a goal of Healthy People 20206.

A substantial amount of the literature on health disparities experienced by sexual and gender minorities focuses on urban residents7. The accrued knowledge on rural LGBT health has been largely derived from small, non-representative surveys and qualitative studies8. Nonetheless, research indicates that health disparities are prevalent among rural LGBT Americans, and might even be amplified in the context of rurality. For example, rural lesbian women report higher than average weight compared to both rural heterosexual women and urban lesbian women9,10. Rural gay and bisexual men may experience greater psychological distress than their rural heterosexual and urban sexual minority comparators9,11. Suicidal ideation, an established concern for the LGBT community12, appears to affect LGBT individuals residing in rural areas at a higher rate than those residing in urban areas, as well as rural, non-LGBT populations13.

Barriers to care experienced by rural LGBT persons might be different from those experienced by their urban and non-LGBT counterparts14, and could help explain these health disparities. Healthcare barriers can be described as systematic obstacles resulting in part from social, economic, or environmental inequalities that prevent marginalized groups from accessing services and attaining their full health potential15. These include high costs, inadequate or lack of insurance coverage, and unavailability of services, as well as lack of culturally competent health care16. The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities recognizes both underserved rural populations, and sexual and gender minorities, as ‘health disparity populations’ that may experience such barriers17.

Feelings of anticipated stigma (concern about possible future instances of discrimination), as well as instances of enacted stigma (actual instances of experienced discrimination) while interacting with healthcare providers have also been documented among rural LGBT persons18-23. For example, in a study involving rural lesbian and gay elders caring for their partners with Alzheimer’s disease or related dementia, participants reported being questioned about their same-sex relationships, being treated with disrespect, and being met with antipathy from their partners’ healthcare providers20. Adverse impacts of anticipated and enacted stigma among rural LGBT individuals include a greater likelihood of delaying or avoiding health services18,19; not revealing their sexual or gender identities, which can result in the inadequate receipt of preventive screenings21,22; and poorer overall health in general23.

An initial step in developing effective interventions to improve healthcare providers’ attitudes towards LGBT patients requires a comprehensive understanding of the prevalence and correlates of these attitudes. Research with urban samples has indicated that personally knowing LGBT individuals24 and having previous professional contact with them25 are associated with generally positive attitudes. Conversely, higher levels of religiosity26 and a heterosexual orientation of the providers themselves27 are associated with generally negative attitudes. Data on the attitudes of rural healthcare providers towards LGBT persons are currently lacking, as noted in a recent literature review8. The study presented here attempts to address this dearth of information using a sample of rural healthcare providers in the US state of Michigan. Specifically, the purpose of this research is to describe existing attitudes of primary care providers in rural Michigan towards gay men, lesbian women, bisexual men, bisexual women, and transgender persons, and to identify independent correlates of these attitudes.

Methods

Recruitment and data collection

Six hundred and twenty potential study participants were identified through a public record of 170 certified rural health clinics across 58 Michigan counties, available through the Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs28. Rural health clinics are medical providers located in non-urbanized areas, as defined by the US Census Bureau, which provide a variety of primary medical care services29. The eligibility criteria included currently practicing as a doctor of medicine, a doctor of osteopathic medicine, a physician assistant, or a nurse practitioner, currently holding primary employment at a Michigan rural health clinic, and currently offering primary medical care services. Primary care providers were specifically targeted for inclusion in this study, because they may be the only accessible healthcare providers for many rural populations30,31.

Informal discussions with a small number of rural primary care providers revealed that many rural health clinics currently only have dial-up Internet connections. Using a web-based survey could be a hindrance to engaging potential participants, and had the potential to create significant bias in sampling. Therefore, the research team elected to conduct a paper-based survey. Utilizing a modified Dillman mail-out method32, all 620 rural healthcare providers identified were mailed a study packet containing (i) a personalized cover letter requesting participation, (ii) an informed consent document, (iii) a copy of the survey, and (iv) a postage-paid return envelope. Dillman recommends a series of rapid reminders after the initial survey mail-out to encourage the target audience to respond32. One week after the original mail-out, a research assistant called each of the 170 clinics, requesting to speak with or leave a message for each of the providers who were mailed a packet, asking them to complete and return the survey. Two weeks after the original mail-out, a reminder postcard was sent to each provider who had not yet returned a response. Finally, three weeks after the original mail-out, a second complete study packet was mailed to each provider who had not yet returned a response. Initial mail-outs were conducted during the first 3 weeks of May 2017, and data collection was completed in July 2017.

Survey measures

The survey instrument comprised 84 questions, with an estimated time for completion being 20–30 minutes, the details of which have been published elsewhere33. Age was measured as a continuous variable, whereas race and ethnicity were measured as categorical variables in two separate questions. Gender identity was described to the participants as ‘an individual’s innermost sense of their gender; it can be the same or different from sex assigned at birth’, and the response options were ‘female’, ‘male’, ‘genderqueer or non-binary’, and ‘other’ with an open-ended text field. The survey also asked participants about their sexual orientation using the following response options: ‘heterosexual/straight’, ‘homosexual/gay’, ‘bisexual’, ‘queer’, and ‘other’ with an open-ended text field. Besides eliciting information on participants’ demographic characteristics and professional background (eg length of time practicing in current role as an MD, DO, PA or NP, length of time holding primary employment at a Michigan rural health clinic, average number of patients seen per day), it assessed their past clinical experiences with sexual and gender minorities and issues pertaining to professional training specific to LGBT health. The survey also included a collection of five Attitudes Toward LGBT People scales, developed by Worthen through principal component factor analyses34. These scales have been previously utilized in the same combination to assess general attitudes towards distinct LGBT subpopulations35-37. Participants were asked to indicate their extent of agreement (1=‘strongly disagree’, 2=‘disagree’, 3=‘neutral’, 4=‘agree’, 5=‘strongly agree’) with a series of items to measure their feelings, thoughts and predicted behaviors towards (i) gay men and (ii) lesbian women (eg feeling comfortable with the thought of same-sex romantic relationships, believing that homosexuality is a psychological disease), (iii) bisexual men and (iv) bisexual women (eg thinking that most bisexual individuals are temporarily experimenting with their sexuality, believing that bisexuality is harmful to society because it breaks down natural divisions between the sexes), and (v) transgender persons (eg believing that sex change operations are morally wrong). Finally, participants were asked to opine on general health care in rural Michigan. No monetary incentives were provided for completing the survey.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SAS Analytics Software v9.4 (SAS Institute; http://www.sas.com). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the overall characteristics of the sample. Responses to participants’ levels of agreement with each item in each of the five attitude scales corresponding to specific LGBT subpopulations (gay men, lesbian women, bisexual men, bisexual women, and transgender persons) were combined to generate five corresponding attitude scores34,35. Because the number of items in each scale were different (14 for gay men, 14 for lesbian women, 4 for bisexual men, 4 for bisexual women, and 8 for transgender persons), the scores were standardized to range from 1 (reflecting least favorable attitudes) to 5 (reflecting most favorable attitudes)38. Kruskal–Wallis tests were performed to assess global differences in the attitude scores for each subpopulation across strata of the following participant characteristics: age, race/ethnicity, gender identity, religion, religiosity level, having personal contacts who identify as LGBT, having provided services to patients who revealed their LGBT identity, believing that knowledge of LGBT identity is important for optimal healthcare provision, receiving education specific to LGBT health during their professional degree program, and believing that such education should be required for all primary care providers. Because of an a priori decision to conduct 10 independent tests for each subpopulation, the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was employed to adjust for multiple comparisons39. The false discovery rate (the rate at which characteristics deemed significant are truly null) was limited to 5%. Finally, separate multivariable linear regression models including only significant characteristics identified in Kruskal–Wallis tests were formulated to evaluate independent correlates of attitudes towards each subpopulation.

Ethics approval

Study procedures and materials were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan (HUM00125386).

Results

Sample characteristics

Between May and July 2017, 123 of 620 potential participants (19.84%) who were mailed study packets and sent a series of reminders returned the survey. Responses came from 45 of the 58 Michigan counties with operational rural health clinics. Of these 123 individuals, 113 (91.87%) provided complete data on each item in the five scales assessing attitudes towards distinct LGBT subpopulations, and were included in the analytic sample. No significant differences in demographic characteristics were observed between these participants and the 10 individuals who were excluded due to missing data.

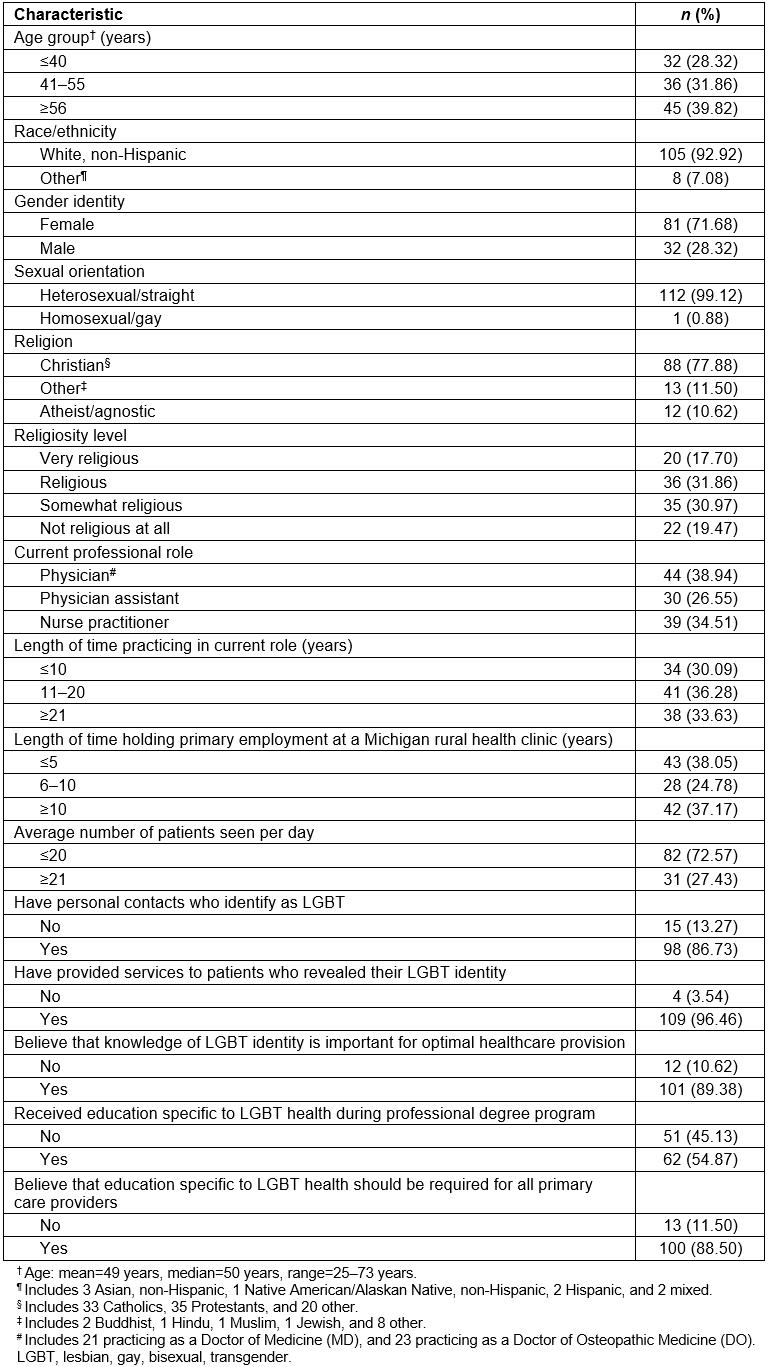

Descriptive characteristics of the 113 participants are presented in Table 1. Age range was 25 to 73 years (mean=49 years), and the majority were non-Hispanic white (92.92%). Eighty-one (71.68%) were female, 32 (28.32%) were male, and none were genderqueer or non-binary, or any other gender identity. Only one participant (0.88%) identified as homosexual/gay, and none identified as bisexual, queer, or any other sexual orientation. More than three-quarters (77.88%) identified with a Christian faith, and most participants indicated being somewhat religious (30.97%), religious (31.86%), or very religious (17.70%). Twenty-one (18.58%) were currently practicing as an MD, 23 (20.35%) as a DO, 30 (26.55%) as a PA, and 39 (34.51%) as an NP. More than three-fifths (61.95%) reported holding primary employment at a Michigan rural health clinic for 6 or more years.

Regarding previous experiences with sexual and gender minority individuals, most participants (86.73%) had personal contacts who identify as LGBT. Almost all (96.46%) had provided services to patients who revealed their LGBT identity, and the majority (89.38%) believed that knowledge of LGBT identity is important for optimal healthcare provision. Nearly half (45.13%) reported not having received education specific to LGBT health during their professional degree program. However, most participants (88.50%) believed that such education should be required for all primary care providers.

Table 1: Descriptive characteristics of 113 rural primary care providers, Michigan, USA, May–July 2017

Provider attitudes towards LGBT persons

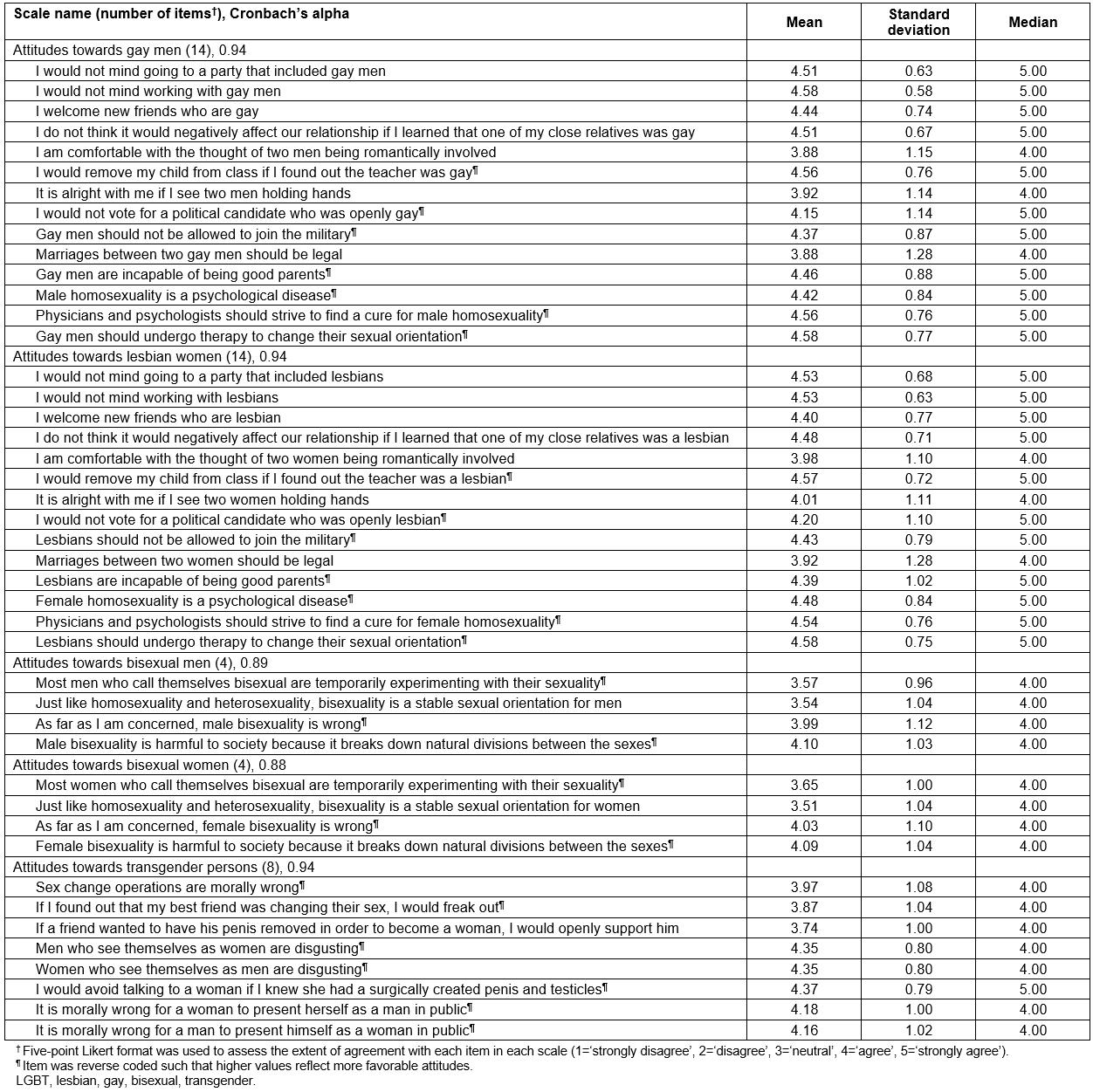

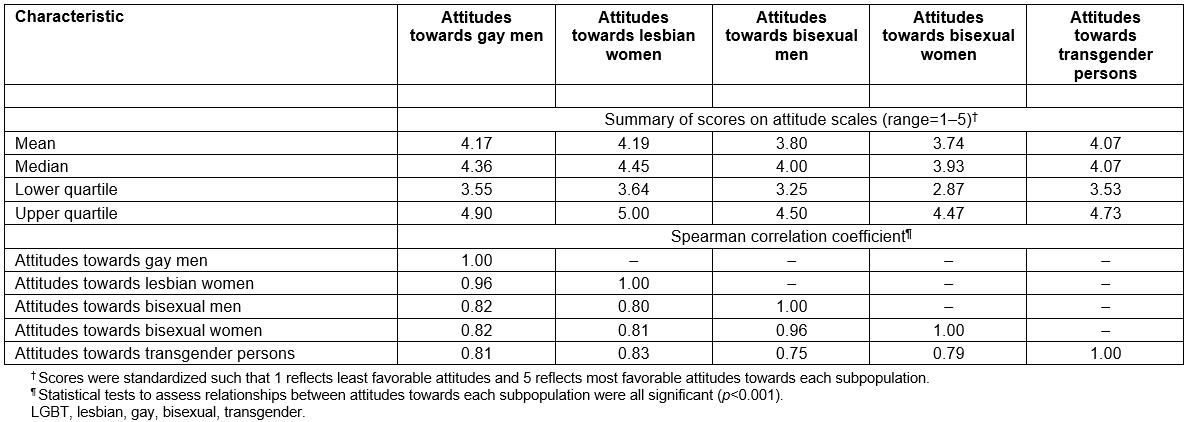

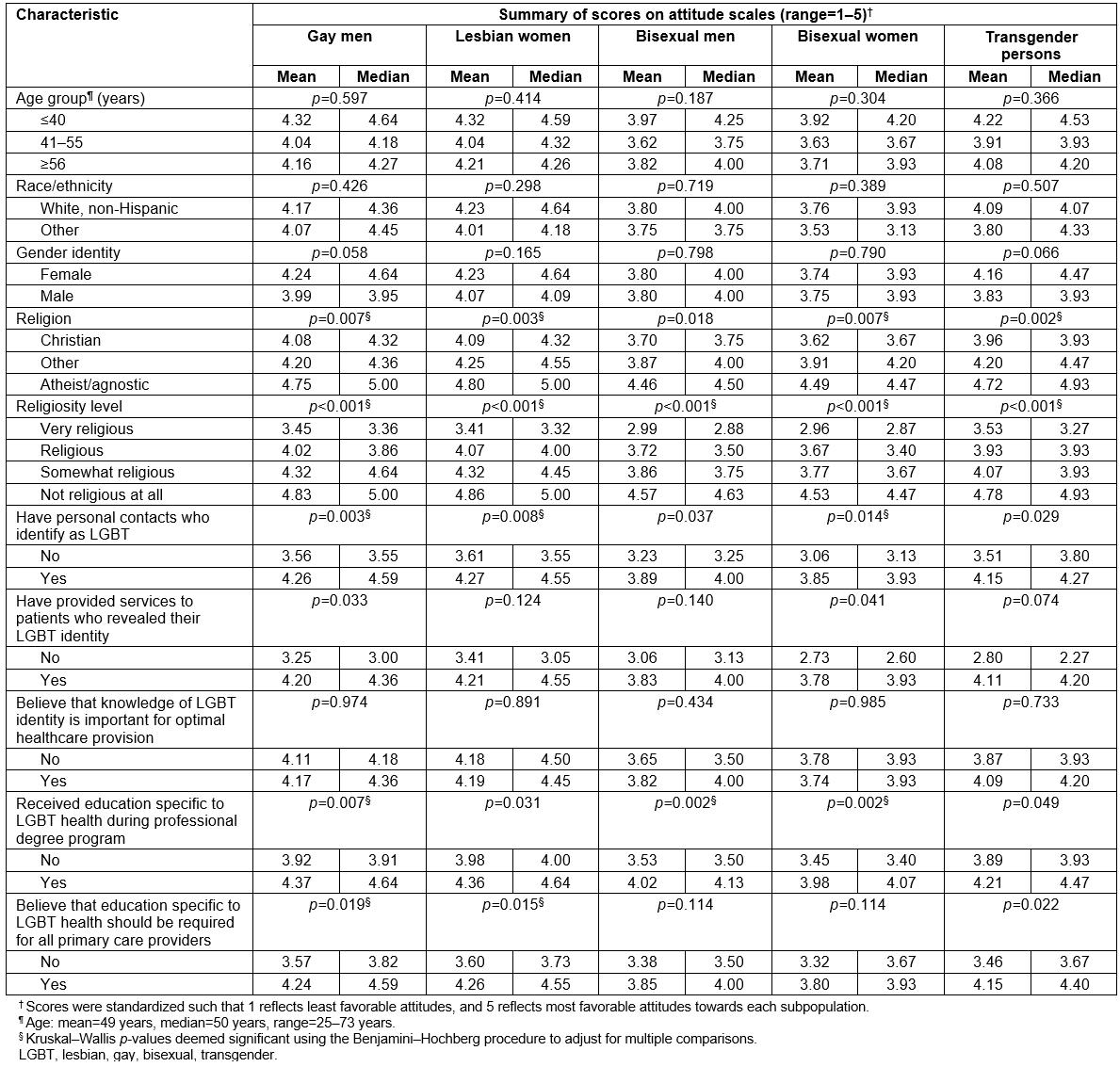

Individual items comprising the five Attitudes Toward LGBT People scales to assess rural primary care providers’ attitudes are described in Table 2. Cronbach’s alpha values for each scale were approximately equal to 0.90, reflecting excellent internal consistency40. The overall attitudes of participants towards gay men, lesbian women, bisexual men, bisexual women, and transgender persons, and their correlations, are summarized in Table 3. Distributions for each of the five scales were skewed to the left, indicating generally favorable attitudes towards LGBT individuals. All Spearman correlation coefficients were greater than 0.70, indicating strong positive relationships between attitudes towards each LGBT subpopulation41. Attitude scores stratified by selected participant characteristics are presented in Table 4, and described in detail below.

Table 2: Items comprising scales to assess attitudes of 113 rural primary care providers towards distinct LGBT subpopulations, Michigan, USA, May to July 2017

Table 3: Overall attitudes of 113 rural primary care providers towards distinct LGBT subpopulations, and their correlations, Michigan, USA, May to July 2017

Table 4: Attitudes of 113 rural primary care providers towards distinct LGBT subpopulations stratified by selected characteristics, Michigan, USA, May to July 2017

Correlates of attitudes towards gay men and lesbian women

On adjusting for multiple comparisons, Kruskal–Wallis tests indicated significant differences in attitudes towards gay men across strata of religion and religiosity level, with relatively low scores noted for those identifying with a Christian faith, and progressively decreasing scores noted with increasing levels of religiosity. Participants who did not have personal contacts who identify as LGBT also had significantly less favorable attitudes towards gay men. However, those who had received education specific to LGBT health during their professional degree program, and those who believed that such education should be required for all primary care providers, had significantly more favorable attitudes. Multivariable linear regression modeling identified associations with religiosity level (p<0.001), having received education specific to LGBT health (p=0.044), and believing that such education should be required (p=0.003).

Regarding attitudes towards lesbian women, Kruskal–Wallis tests indicated significant differences across strata of religion and religiosity level, with the magnitude and direction of results paralleling those observed for gay men. Participants who had personal contacts who identify as LGBT, and those who believed that education specific to LGBT health should be required for all primary care providers, had more favorable attitudes towards lesbian women. The multivariable analysis identified significant relationships with religiosity level (p<0.001), and believing that education specific to LGBT health should be required (p=0.001).

Correlates of attitudes towards bisexual men and women

Significant differences in participants’ attitudes towards bisexual men were observed across strata of religiosity level, and having received education specific to LGBT health during their professional degree program in Kruskal–Wallis tests, adjusted for multiple comparisons. Results from the multivariable linear regression model indicate that higher levels of religiosity (p<0.001) and not having received education specific to LGBT health (p=0.008) were both independently associated with less favorable attitudes.

Regarding attitudes towards bisexual women, Kruskal–Wallis tests indicated significant differences across strata of religion, religiosity level, having personal contacts who identify as LGBT, and having received education specific to LGBT health, with the results being in the same directions as those for gay men, lesbian women, and bisexual men. Multivariable linear regression modeling identified associations with religiosity level (p<0.001), and having received education specific to LGBT health during their professional degree program (p=0.005).

Correlates of attitudes towards transgender persons

Kruskal–Wallis tests, adjusted for multiple comparisons, revealed significant differences in participants’ attitudes towards transgender persons across strata of religion and religiosity level, with the direction of results paralleling those observed for other subpopulations. Only higher levels of religiosity were independently associated with less favorable attitudes (p=0.001) in the multivariable analysis.

Discussion

In light of the current paucity of data on attitudes of rural healthcare providers towards LGBT individuals in the US8, this research fills a critical gap in the extant literature. Survey results revealed generally positive attitudes of primary care providers in rural Michigan towards gay men, lesbian women, bisexual men, bisexual women, and transgender persons. This is encouraging given the documented associations between experiences of healthcare-associated stigma and negative health outcomes among rural sexual and gender minorities18-23. Multivariable regression analyses identified significant correlates of rural provider attitudes towards distinct LGBT subpopulations. Variations across levels of religiosity, a somewhat immutable characteristic, are consistent with recent studies examining the relationship between providers’ personal beliefs and their views of LGBT patients26,42,43. Variations across the previous receipt of education specific to LGBT health, and believing that such education should be required for all primary care providers, support the need for interventions to improve cultural competency among rural healthcare providers.

LGBT individuals residing in rural areas might be particularly vulnerable to poor physical and mental health outcomes on account of their geographic isolation and residence in communities in which their identities are stigmatized, as well as other sociocultural factors made salient at the intersection of these two aspects44. Prior research with rural LGBT persons has identified a vast array of healthcare barriers, including difficulties in transportation to urban health centers18,45, lack of social support13,46, suboptimal health insurance coverage11,47, financial constraints18,47, hostile environments48,49, and rural cultural mores regarding sexuality and gender46,50. Primary care providers may be the only accessible healthcare providers in some rural communities30,31, and are uniquely poised to offer vital prevention, screening, and treatment services for LGBT patients throughout their life course14. The generally favorable attitudes of rural providers towards LGBT subpopulations noted in this sample align with results from studies involving predominantly urban samples25,51. This may reflect temporal shifts in the general US population, which is increasingly embracing a more inclusive view of sexual and gender identities52. Establishing long-term relationships with local LGBT-friendly providers could be a mechanism to reduce both anticipated and enacted stigma experienced by rural LGBT patients23.

Despite recent indications that the personal attitudes of providers towards LGBT individuals are improving51,53, they may continue to be influenced by religion and varying levels of religiosity. For example, a national online study involving 1166 nurse educators found a strong association between higher degrees of religious observance and progressively negative attitudes towards LGBT persons26. In Georgia, higher levels of religiosity and lower levels of familiarity with different religious perspectives on sex were associated with less favorable attitudes towards LGBT patients43. In Tennessee, some medical providers cited religious freedom, without being specifically prompted to discuss this issue, as a reason to deny treatment to LGBT patients42. In this study involving rural primary care providers in Michigan, increasing levels of religiosity were independently associated with less favorable attitudes towards gay men, lesbian women, bisexual men, bisexual women, and transgender persons. However, religion was not associated with attitudes towards each subpopulation after adjusting for religiosity level. Although personal contact with LGBT persons has been found to counteract potential negative influences that increasing religiosity levels may have towards harboring unfavorable attitudes towards the community26,54, this phenomenon was not observed in the multivariable analyses. But given that almost the entire sample had previously provided services to patients who revealed their LGBT identity, there appears to be a separation between one’s personal beliefs and professional responsibilities. Social justice advocacy organizations support the provision of high-quality care based on medical best practices and the health needs of a patient, as opposed to the moral or religious beliefs of the provider55. Further research with larger samples of rural providers across the USA is needed to better understand how religion and varying religiosity levels impact optimal healthcare delivery to sexual and gender minorities.

The vital needs for cultivating core competencies in LGBT health provision among emerging healthcare professionals, and creating healthcare environments that are welcoming, inclusive and protective are increasingly being recognized56. Recent studies with predominantly urban samples have revealed an implicit provider preference favoring heterosexual individuals over gay men and lesbian women57, a belief among some providers that knowledge of a patient’s sexual or gender identity is irrelevant to providing medical care58, and a lack of professional training in LGBT health issues59. In recognition of the significance of provider stigma as a potential threat to the health of LGBT individuals, the US Department of Health and Human Services60, the Association of American Medical Colleges61, and the Institute of Medicine62 have all called for enhancing provider education and sensitivity towards LGBT patients. Although the majority of this sample believed that education specific to LGBT health should be required for all primary care providers, only slightly over half reported receiving such education during their professional degree program. Not surprisingly, both variables were independently associated with more favorable attitudes towards LGBT persons. Future institutional efforts could include assessments of the existing curricular content, and enhancing student’s knowledge about the social and economic realities faced by LGBT patients. Results from a Canadian study demonstrate that an LGBT-focused curriculum recently introduced at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine has been effective in increasing medical students’ knowledge on LGBT health issues, regardless of their pre-existing levels of awareness63. A similar finding was observed in a study examining the effectiveness of an educational intervention designed to improve knowledge and attitudes regarding LGBT-specific health care among nursing students in Illinois64. Incorporating trainings on sexual and gender diversity, and the unique healthcare needs of rural LGBT patients may help create more culturally competent providers.

Study limitations

Despite being among the first to examine attitudes of rural healthcare providers towards LGBT individuals, this study is not without limitations. Participant recruitment might have been limited by relying solely on the Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs’ public record of certified rural health clinics28, as there may be other locations that also provide services to rural LGBT patients. Given the focus on Michigan, these results cannot be generalized to rural providers in other US states. Only one-fifth of potential participants actually returned the paper-based survey. Non-response could have been due to the survey’s length, or because of concerns around confidentiality, especially among providers who suspected that their opinions might be viewed negatively. One cannot rule out the possibility of social desirability bias when responding to items on the attitude scales, which might have overestimated the prevalence of favorable attitudes of rural providers towards LGBT patients noted in this sample. Another limitation is that the sample was predominantly non-Hispanic white and female. Previous research evaluating racial/ethnic differences in attitudes towards sexual and gender minorities in the general population has found mixed results65,66, but women have been consistently documented to express more positive attitudes than men67-70, a trend that might explain the overall favorable attitudes observed in this study. Using single-item measures to assess religion and religiosity level limits the ability to establish the validity or reliability of these constructs. Finally, the authors acknowledge that the lack of information on attitudes among urban healthcare providers towards LGBT individuals precludes a direct comparison between rural and urban settings in Michigan.

Conclusion

This study illuminates the realistic potential for heterogeneity in high-quality healthcare provision to rural LGBT patients, and reveals some noteworthy points of future programmatic intervention. Educational opportunities, perhaps in the form of workshops and seminars, must be afforded to providers across the spectrum of healthcare fields to learn about the characteristics and specific needs of sexual and gender minorities. This might help improve attitudes and understanding among those who are not entirely comfortable with LGBT individuals, possibly due to their higher degrees of religious observance. Accurate, unbiased, and nonjudgmental content about the health risks and care guidelines pertaining to the LGBT community should continue being incorporated into the curricula of medical, nursing, dentistry, pharmacy, and other health professional schools. Ensuring the delivery of culturally competent care to rural LGBT individuals will require multi-level systemic changes that include ongoing provider trainings, enhancing physical healthcare environments, support from the administration, and increasing staff diversity.

references:

You might also be interested in:

2020 - Barriers and bridges to implementing a workplace wellness project in Alaska