Introduction

There is an inconsistent provision of palliative and end-of-life (henceforth, palliative) care across Australia, particularly in regional, rural and remote areas1,2. Effective palliative care improves quality of life and the experience of dying through early identification, assessment and treatment of physical, psychological, social, cultural and spiritual symptoms and needs, respecting a patient’s care preferences, and supporting their carers and family in bereavement3,4. Systematic solutions can help to address identified gaps and improve access to and quality of care and support for patients, their families and carers at the end of life1,2.

Australia’s National Palliative Care Strategy advocates for the provision of appropriate and quality palliative care in a suitable setting from providers with capacity and capability3. It is the vision in New South Wales (NSW) that everyone should ‘have equitable access to quality care based on assessed need as they approach and reach the end of life’ thereby making palliative care everyone’s business5. There is a reliance on generalist clinicians to provide palliative care (generalists are not specialist palliative care clinicians but may be specialists in their own discipline), yet generalists report feeling ill-equipped to provide palliative care to their patients, particularly in rural and remote regions where provision of quality health care has well-recognised challenges of infrequent case exposure, limited workforce, poorer access and vast geography6-13.

A palliative approach to care is the collaborative provision of care by generalist, aged care and specialist providers, who identify and holistically address the physical, emotional, spiritual, cultural and social needs of a person and their family. Such care aims to support a person with a life-limiting illness to live as well as possible until they die by maintaining quality of life, and to support their families14. It also improves patient care and outcomes in the last year of life, including fewer hospital admissions and more people dying at home rather than in hospital3,15,16. A palliative approach is a logical response, particularly where there are known gaps, such as a lack of clearly defined roles and coordination of care across provider groups, and in rural and remote communities where access to care is limited due to distance as well as workforce and resource shortages6,7,13,17,18.

The Far West NSW Palliative and End of Life Model of Care is proposed to be a systematic solution for a rural and remote palliative approach to care. The model was developed to enable a consistent and contextually adaptable, patient-focused palliative approach to care so that everyone gets the care they need from appropriately skilled and informed clinicians, in a timely manner, and as close to home as possible19,20. While this is not the first model to support a palliative approach, it provides a uniquely rural response to providing palliative care in Australia15,16,21,22. This narrative report aims to:

- describe the development, design and function of the model

- identify the essential elements to implement or maintain the model elsewhere.

Methods

This narrative report was produced and written from the perspective and experience of key informants, select persons involved in establishing the Far West NSW Palliative and End of Life Model of Care. Informants (authors SW and MC) were purposively selected because they were leaders in the development and establishment of the model within rural and remote communities of far west NSW23. Co-author ES, as an external researcher, reviewed literature as well as internal documents positioning the model and held informal discussions with key informants collecting information on the design, development and function of the model. Quotations in this article come from those discussions. Key informant reflections were also reviewed through a cyclical process of generic qualitative inquiry and analysis to generate and confirm the essential elements of the model. A limitation of this review may be the reliance on a small informant group; however, it is a small team and additional informants may not have enhanced the understanding of the model to such detail.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted through the Greater Western Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/16/GWAHS/136).

Results

Setting

The model was developed in the Far West Local Health District (FWLHD), which serves about 30 000 people, more than 12% of whom identify as Aboriginal. The FWLHD is classified as remote, covering the western third of NSW (approximately 200 000 km2), and bordering three states (Queensland, South Australia and Victoria)24. The provision of palliative care in Australia is variable and, in contrast to many remote regions, a specialist palliative care service (SPCS) has been operating throughout the FWLHD since 1989, providing access to 24-hour palliative care, education and collaboration with generalist providers (including those working in hospital, primary health care, residential aged care facilities and community-based services)25.

Far West NSW Palliative and End of Life Model of Care

The model was developed to be adaptable and relevant for all rural and metropolitan services, including those that have variable access to resources and providers, as it promotes a palliative approach to care that is applicable across services, sites, settings and providers.

The intention of the model is to:

- enhance the local provision of a palliative approach to care for patients, their families and carers

-

improve clinical outcomes for people approaching the end of their lives through:

- earlier identification of need for a palliative approach

- advance care planning

- appropriate care in the last days of life

- patient-centred care

- enable communication, integration and collaboration between providers and care settings

- build and maintain a skilled and confident workforce

- extend capacity of the local SPCS.

Model development, design and function

The model began to take shape in 2012 when resources, funding, interests and opportunities aligned. A specialist palliative physician from the UK who had experience with the implementation of the North West End of Life Care Model, a best-practice specialist palliative care model in the UK, joined the SPCS that year26. The UK model was useful for sharing the details of a specialist palliative service, but far west NSW needed a whole-of-system and inclusive response that would support a culturally relevant palliative approach to care. The UK model was adapted for the context of rural and remote Australia and integrated the five clinically meaningful palliative care phases used to define the Australian national case-mix classification (stable, unstable, deteriorating, terminal, bereavement)27,28. This was a catalyst to formalise and build upon established key clinical specialist palliative care processes and adapt them for application in generalist services, thereby ensuring a consistent and quality palliative approach to care for anyone in need23.

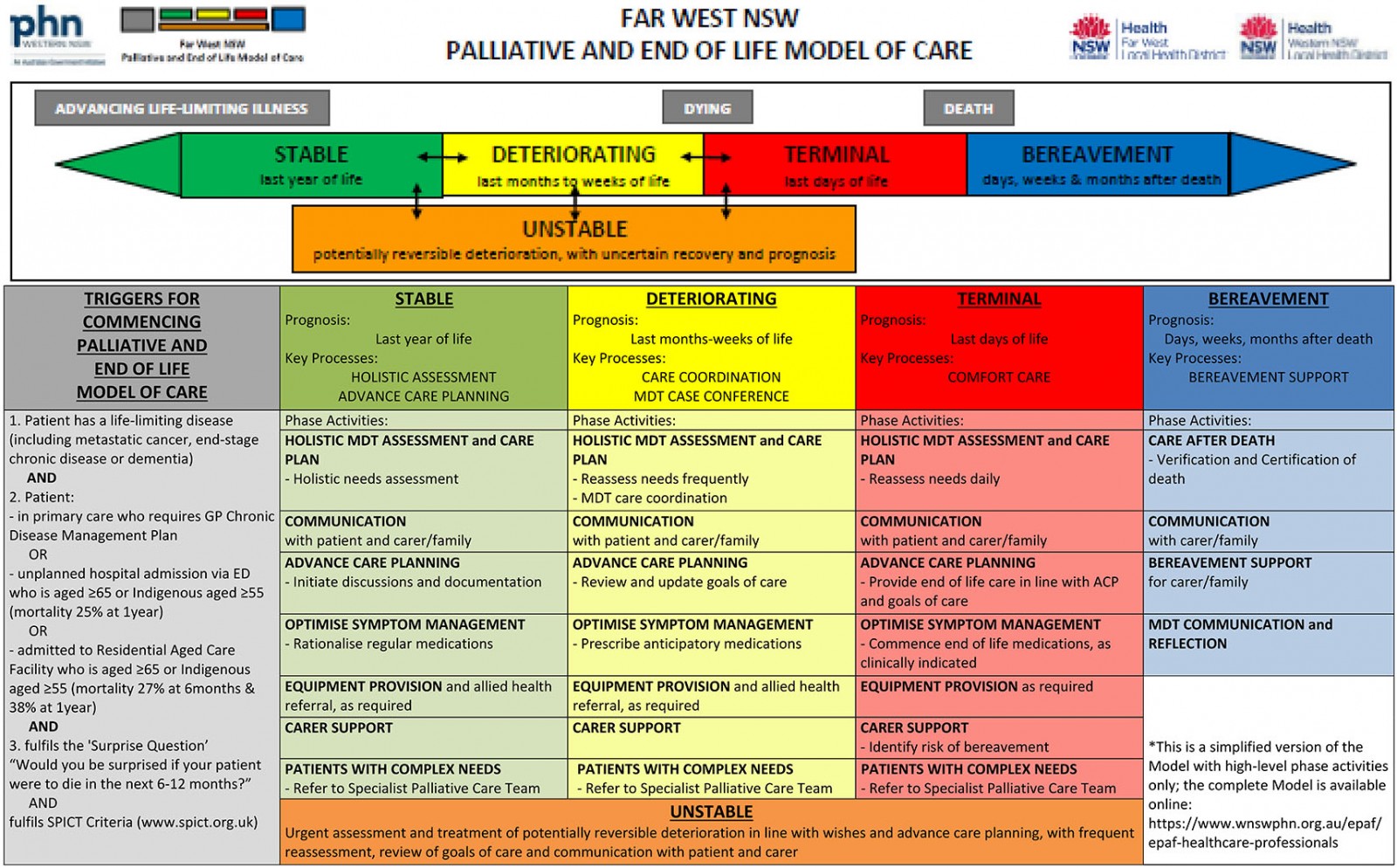

The Far West NSW Palliative and End of Life Model of Care was designed to guide a palliative approach to care in the last year of life, through death and into bereavement (Fig1). The model functions as the scaffolding for locally, culturally and contextually relevant components of a quality palliative approach to care in consideration of a person’s wishes. The model is purposely revisable, ensuring current quality standards are being applied locally. It is also non-prescriptive so that relevant and respectful practice can be applied as appropriate, respecting Indigenous and all other cultures in Australia. This does not define or put boundaries upon relevant and respectful care but recognises the importance of establishing relationships to ensure appropriate care. This makes the model a systematic yet contextually responsive solution for improving palliative care along every person’s journey, regardless of age, diagnosis, culture, location or provider.

The development of the model was led by the SPCS; they are not only aware of best practice, but can drive evidence-based care in the generalist space by sharing knowledge, tools and support. The model can be responsive to state-level palliative care policies or directives, such as the NSW Health End of Life and Palliative Care Framework 2019–2024, Framework for the Statewide Model for Palliative and End of Life Care Service Provision, and Palliative and End of Life Care – A Blueprint for Improvement5,19,29. The model can also include mandated or state-endorsed documents and forms, such as Advance Care Plans or NSW Health Advance Care Directives, the NSW Health Resuscitation Plans and the Last Days of Life Toolkit from the Clinical Excellence Commission30-33. According to one key informant:

It’s actually about … what is already around me that I don’t have to develop. Don’t write a new resus plan, every state will have a resus plan, use it. … There’s stuff out there for all of these things, you’ve just got to choose what works for your location.

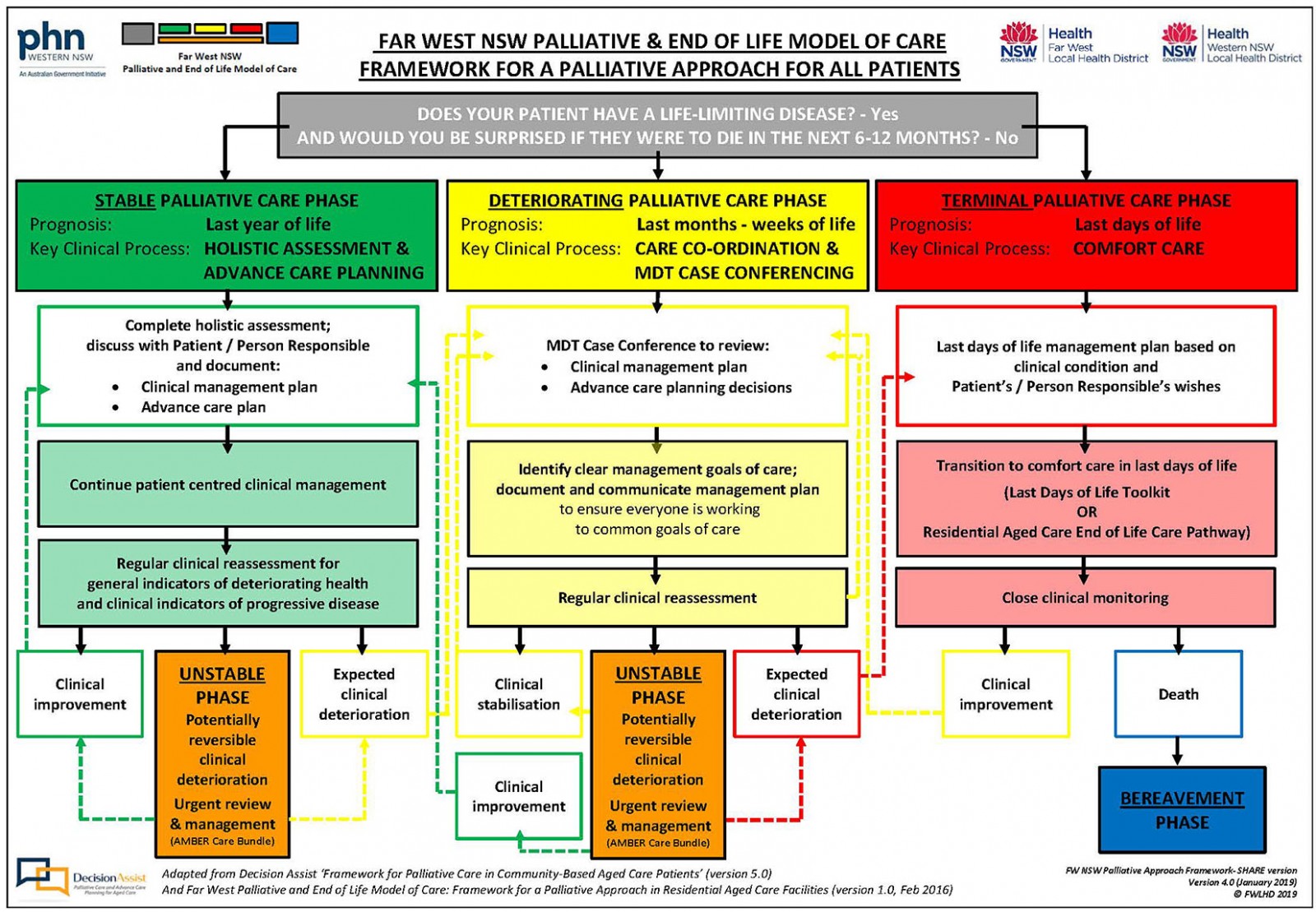

It can also incorporate national or state palliative programs like the then available Decision Assist or NSW Health last-days-of-life home support services (Hammond Care)34,35. For example, the Framework for Palliative Care in Community-Based Aged Care Patients is a Decision Assist tool modified to align with the model, thus enhancing its application for residential care (Fig2).

Functionally, the model introduced evidence-based triggers to assist earlier identification of people who would benefit from a palliative approach36-38. Earlier identification can change the course of care and quality of life. The inclusion of prognostic indicators, clinical prompts and key palliative care processes, such as care planning and comfort care, assist the provision of evidence-based multidisciplinary care and support the transition of care for patients and their families within the five palliative care phases.

The model is adaptable and inclusive, making it relevant and applicable for various health settings and conditions. Combining international, evidence-based best-practice with national, state and local clinical standards aids engagement and confidence for use, thereby extending the capacity of the SPCS to support complex cases. For instance, the application of standard medication guidelines has helped to ensure patients are prescribed appropriate palliative medications as needed. Building upon established relationships with local pharmacists and general practitioners helped to ensure timely and pre-emptive access to such medications.

Figure 1: The Far West NSW Palliative and End of Life Model of Care.

Figure 1: The Far West NSW Palliative and End of Life Model of Care.

Figure 2: The model-modified Decision Assist framework for palliative care.

Figure 2: The model-modified Decision Assist framework for palliative care.

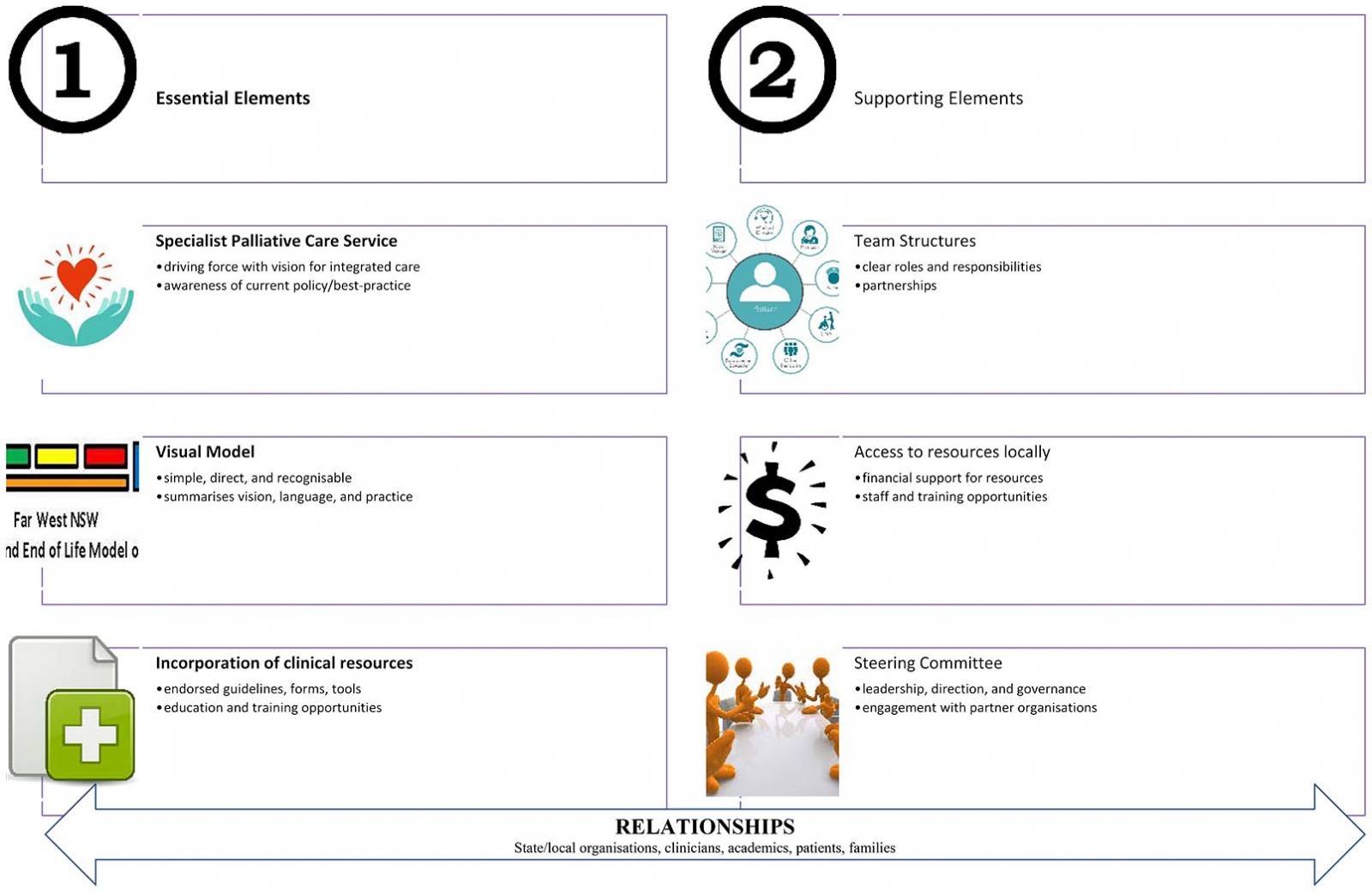

Essential elements

There were three essential elements to the development and maintenance of the model. These elements are necessary to implement and maintain a palliative approach to care using the model elsewhere. The first essential element is the local specialist palliative care service. They are a driving force who must have a vision and desire for integrated and patient-centred care, an awareness and radar for current policy and best practice, and a genuine relationship with community partners. The second essential element is having the visual representation of the model – something simple, direct and recognisable that summarises the vision, language, practice and expectation for a shared palliative approach to care within all five palliative phases. The third essential element is incorporating key clinical guidelines, forms and tools, along with regular education and training opportunities, to maintain awareness and the application of the model. When everyone is working with the same resources and using the same language, there is a consistency and comparability of care (Fig3).

There are three additional supporting elements to consider when implementing the model. First is having team structures with clear roles and responsibilities, as described by a key informant:

Yes, you need somebody to drive it and the vision, but you need that partnership as well, and you need somebody committed to the ongoing education and training.

The second supporting element is access to care and resources within the local context; this includes harnessing financial support through grants or local generosity to fund needed equipment or other resources, as well as new staff positions and training opportunities. Third is having strategic leadership and governing direction from a palliative and end-of-life steering committee that aids awareness and the consistent application of the model.

All of this activity is underscored by relationships – whether at state or local levels, with other clinicians or academics, or with the patients and their families. Without these working relationships, the model would not be what it is, nor would it be possible to implement or maintain a palliative approach to care.

Figure 3: Essential and supporting elements for maintaining (or implementing) the model and a palliative approach to care.

Figure 3: Essential and supporting elements for maintaining (or implementing) the model and a palliative approach to care.

Promotion (the future)

The vision is to provide coordinated, consistent, quality, palliative approach to care for all residents in their place of choice with the application of the model. The model offers a basic design within which evidence-based practice and tools are applied, and this can change the experience of dying. The ability of the model to systematise a palliative approach and be contextually relevant ensures consistent quality care and enables transferability.

Model 2.0 is now available with the digital development of the Far West Electronic Palliative Approach Framework (ePAF) and a shared health record39. The model is unchanged, and the functionally supportive documents and resources are now available electronically. This will bridge clinical care settings and enable clinicians to provide a timely, consistent, safe and contextually appropriate palliative approach to care. Model 2.0 is readily translatable to other care locations, including regional and metropolitan areas. Further research to examine the influence of the model on the provision of palliative care, as well as its digital variation, is needed.

Conclusion

The Far West NSW Palliative and End of Life Model of Care is a simple, systematic and translatable solution. It has the potential to enable a consistent yet contextually adaptable, patient-focused palliative approach to care, whether in remote towns or metropolitan cities. With the model, everyone can receive the palliative care they need from appropriately skilled clinicians, in a timely manner, and as close to home as possible.

References

You might also be interested in:

2019 - Outreach specialist's use of video consultations in rural Victoria: a cross-sectional survey