Introduction

The geographic maldistribution of healthcare workers between urban and rural or remote areas is globally recognised1. People living rurally commonly have poorer health status, shorter life expectancy and higher mortality rates than those living in urban locations2. Workforce undersupply, high levels of workforce turnover and difficulties recruiting to these locations disadvantage these populations and reduce timely access to healthcare services3,4. Retaining an adequate and appropriately qualified health workforce is a key element in the provision of accessible and high-quality primary health care4,5. It is therefore critical that factors affect recruitment and retention of healthcare workers are understood for the development of rural health workforce policy as well as local, state and national recruitment and retention strategies.

Podiatrists are an essential allied health profession. They are integral to the primary care rehabilitation and acute service models required to service communities as small as 1000 people6. General practitioners are increasingly reliant on the podiatry profession to assist people who are at great risk of foot problems7. The podiatry workforce improves health outcomes and quality of life and reduces amputation rates for many people, including those who have complications of diabetes such as neuropathic foot disease, foot pain and vascular impairment8. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians are more likely to develop foot complications, including foot ulceration, amputation and peripheral neuropathy, than non-Indigenous Australians9. Of the total population living in remote areas, the proportion of Indigenous Australians is relatively high10, exacerbating these problems due to challenging engagement with existing services and healthcare service availability11. Approximately 340 (6%) Australian podiatrists are located in outer regional, remote or very remote settings12,13. In major cities, there are 16 podiatrists per 100 000 people; however, in outer regional or remote settings these numbers are 6.4–10.4 podiatrists per 100 00013. Rates of amputation are higher for people living outside metropolitan settings, yet these are precisely the areas where there are limited podiatry services14.

Significant research has been undertaken to address medical workforce shortages in rural and remote areas. The Medicine in Australia: Balancing Employment and Life (MABEL) longitudinal survey has collected detailed information on medical practitioners’ working lives since 200815. The results have been used to understand factors influencing workplace location choices and to develop medical retention policies and incentives to persuade more Australian medical graduates to work in rural areas16. Key findings include the importance of rural immersion to attract students into rural practice, and the need for professional support to help mitigate heavy workloads and improvement of rural professional development opportunities16. However, these findings may not be transferable to allied health professionals because of different education pathways, workplace structures and funding systems17.

Evidence guiding attraction of allied health workers to rural practice is not specific to podiatrists. Features improving attraction include exposure to rural practice during training, inclusion of rural content within the curriculum, tertiary scholarships and return of service requirements3,18. Furthermore, opportunities for career development, such as career progression19-22, access to mentors19,20 and ongoing professional development19,20,23,24, are key pull factors for recruitment17. Previous exposure to the location, such as living or studying in rural locations positively affect recruitment19-21,24-27, in addition to family and friends residing in the location19,26. Extrinsic factors known to have a negative impact on retention include poor access to professional development, professional isolation and inadequate supervision28. Positive extrinsic factors include diverse caseloads and rural lifestyle while autonomy and connection to the community were identified as positive intrinsic incentives28. Although different allied health professions share recruitment challenges, there has been limited exploration of podiatrist decision-making about work choices.

The Stronger Rural Health Strategy aims to address the maldistribution of healthcare workers across Australia to meet the needs of rural and remote communities29. The Workforce Incentive Program targets doctors and general practices to improve access to allied health services and supports multidisciplinary teams in general practice30. The Rural Locum Assistance Program31 and Allied Health Rural Generalist Pathway32 are other examples of government initiatives that have been developed to support and develop the rural workforce. Although these initiatives exist, there is no centralised data reporting the effects on workforce outcomes, making it hard to determine the effect it has specifically to the podiatry workforce.

With this background in mind, this study aims were to explore (1) recently graduated podiatrists’ perceptions regarding working rurally and (2) broader industry views of the factors likely to be successful for rural recruitment and retention.

Methods

This was a qualitative study design using focus group and individual interview data from a large workforce study of podiatrist workforce choices33. Findings are reported using Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research Guidelines34.

Participants

The two participating groups were:

- podiatrists working in Victoria, Australia, who had graduated in the past 5 years, who had worked in a rural or regional setting

- stakeholders of the podiatry profession identified as owners of regionally located private practices employing more than five podiatrists in Victoria (identified through Australian Podiatry Association networks), managers of Victorian public health service podiatry departments (identified through the Podiatry Chiefs network supported by the Victorian State Department of Health and Human Services), national allied health professional associations, and organisations advocating for allied health services in rural and remote Australian communities, because the latter groups have broad perspectives of rural allied health workforce maldistribution challenges and solutions.

Procedure

For group 1, recent graduate podiatrists who completed the Wave 1 Podiatrists in Australia: Investigating Graduate Employment (PAIGE) cross-sectional survey were invited to participate in a focus group33. The survey had been promoted through podiatry conferences, social media (Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram) and targeted emails from peak bodies such as the Australian Podiatry Association and Australasian College of Podiatric Surgeons. At the end of the survey, podiatrists were given an option to leave their contact details to participate in a gift card draw. Podiatrists who had graduated in the past 5 years and worked in any location (metropolitan, regional or rural) and who opted to leave their details were invited to join one of two focus groups.

For group 2, key stakeholders’ details were accessed through online searches, the Australian Podiatry Association, and the Victoria Podiatry Chiefs network.

All responding participants (focus groups and interviews; designated P1–15 in quotes herein) provided written informed consent. Focus groups with recent graduate podiatrists were conducted in July 2017, and 15 interviews with stakeholders were conducted between July and August 2018.

Data collection

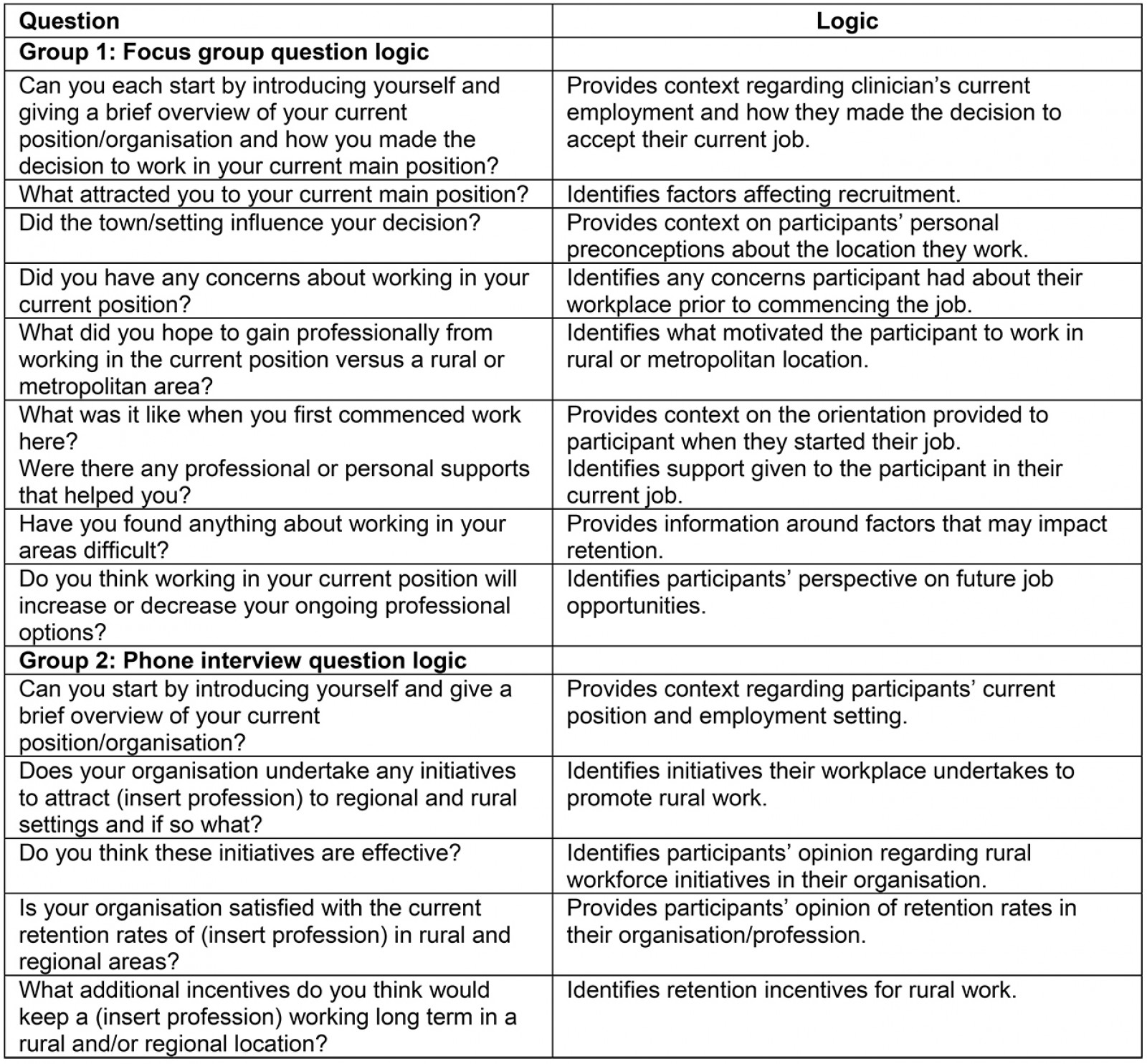

For group 1, data were collected across two online video focus groups (30–60 minutes) and each focus group consisted of up to six participants. Focus groups were conducted to capitalise on group dynamics and facilitate discussion among recently graduated podiatrists35. A moderator who was an experienced qualitative researcher (JW) conducted the focus groups, and a facilitator (AC) took detailed notes informing data analysis. Focus groups were conducted by JW (who is not a podiatrist) to reduce bias and facilitate open discussion. The moderator outlined the discussion purpose and guidelines applying to the focus groups, including confidentiality. A schedule of questions (Supplementary table 1) was utilised to guide the focus groups and promote discussion36.

For group 2, individual semistructured online interviews (15–30 minutes) were undertaken by telephone because the interviewees were distributed across Australia. These interviews were conducted by a researcher who had a podiatry background (AC), who used the wider research team to ensure reflexivity and reduce any subject bias. Individual interviews were considered useful to gather information about stakeholders’ individual perspectives regarding recruitment and retention strategies because they represented different agencies that may have divergent views37.

A semistructured interview guide (Supplementary table 1) was developed at study commencement and refined based on results from focus groups, in order to explore the research question.

Focus groups and phone interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim by an external transcription service. Member checking was conducted to check for accuracy of words, ensuring findings were representative of the participants’ perspectives38.

Supplementary table 1: Focus group and stakeholder interview question logic

Data analysis

All transcribed data were de-identified and focus group data were analysed separately from interview data to separate recent graduate perceptions from industry views. Two authors (JW, AC), independently coded focus group data by using an inductive thematic approach (allowing themes to emerge from the data without a preconceived coding framework)39, and two authors (AC, CW), independently coded the interview data. An inductive thematic approach was employed to explore relationships between themes to offer an explanation for phenomena in the data40. This involved (i) reading transcripts line by line and identifying initial ideas, (ii) generating initial codes across the whole of the dataset, (iii) determining relationships between codes and collating these to form themes, (iv) reviewing themes to ensure relevant to generated codes, (v) generating clear definitions of themes, and (vi) reporting themes using quotes as examples40. Recordings were reviewed independently by the first author (AC) and verbal and non-verbal elements of the focus groups and phone interviews were documented in a reflective journal. The journal was then reviewed during the data analysis phase to examine the researchers’ thoughts and interactions during data collection to enrich the research finding38. Consistency of findings was upheld through discussion of interpretations between researchers to confirm codes and emerging themes and subthemes. The final themes were triangulated by exploring areas where the themes intersected between the two groups. Any differences in researcher perspective were resolved by negotiation and, if necessary, regrouped and recoded until consensus was reached towards the final themes. Trustworthiness of the data was promoted by several strategies, including immersion in data, reflexive analysis, and peer debriefing41,42.

Ethics approval

The Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee, Victoria, Australia, approved this study (MUHREC: 19959).

Results

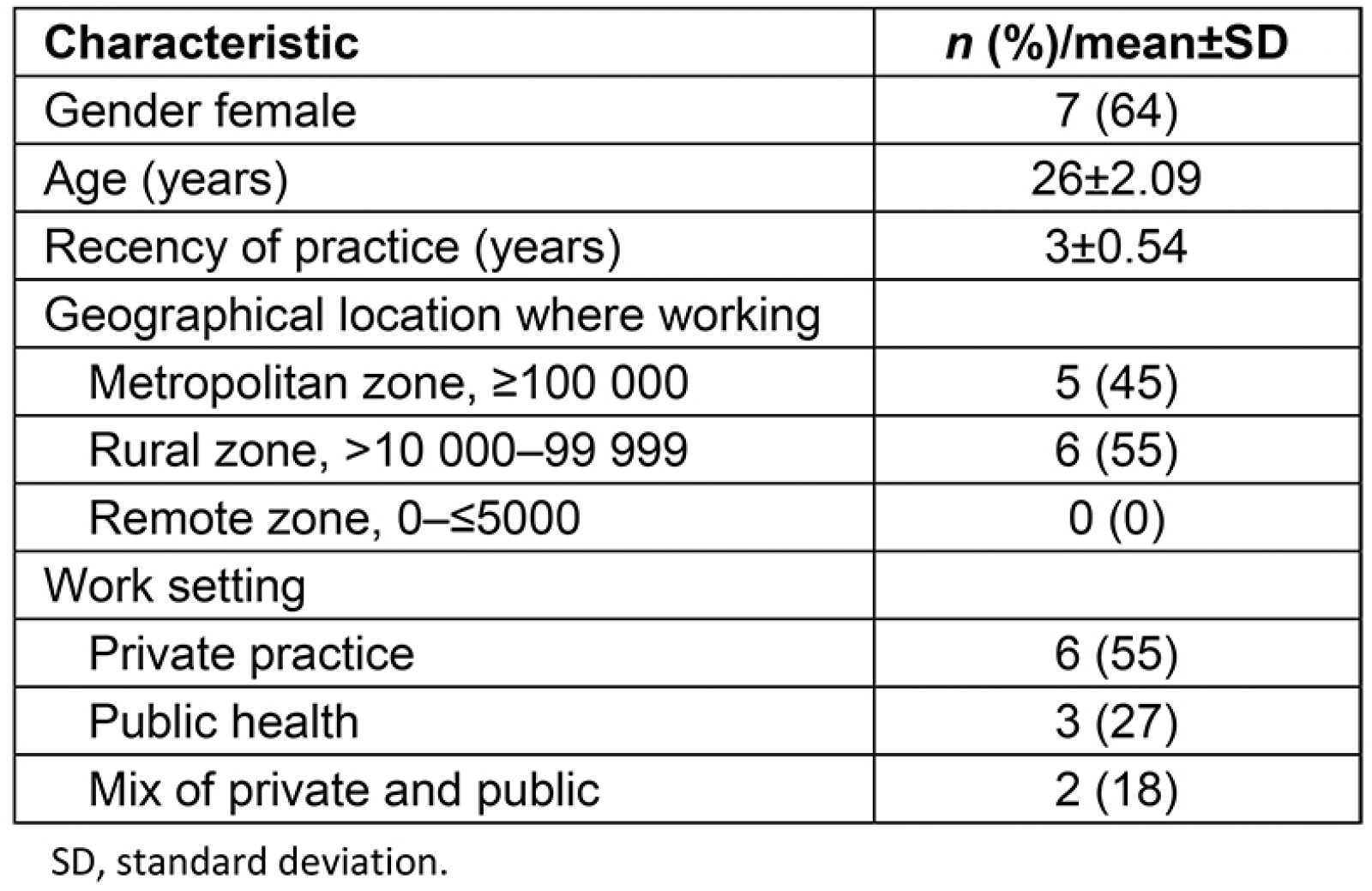

There were 34 podiatrists invited to participate in a focus group and 33 stakeholder interview invitations sent by email. There were 11 podiatrists who gave consent to participate in two focus groups. Participant demographics were summarised by gender, age, recency of practice, geographical working location and current work setting (Table 1). There were 15 stakeholders who participated in one-on-one phone interviews. Participants included nine public health senior managers from regional settings, three private podiatry owners in regional services and three representatives from peak bodies who represented professions whose practitioners may be working regionally or rurally.

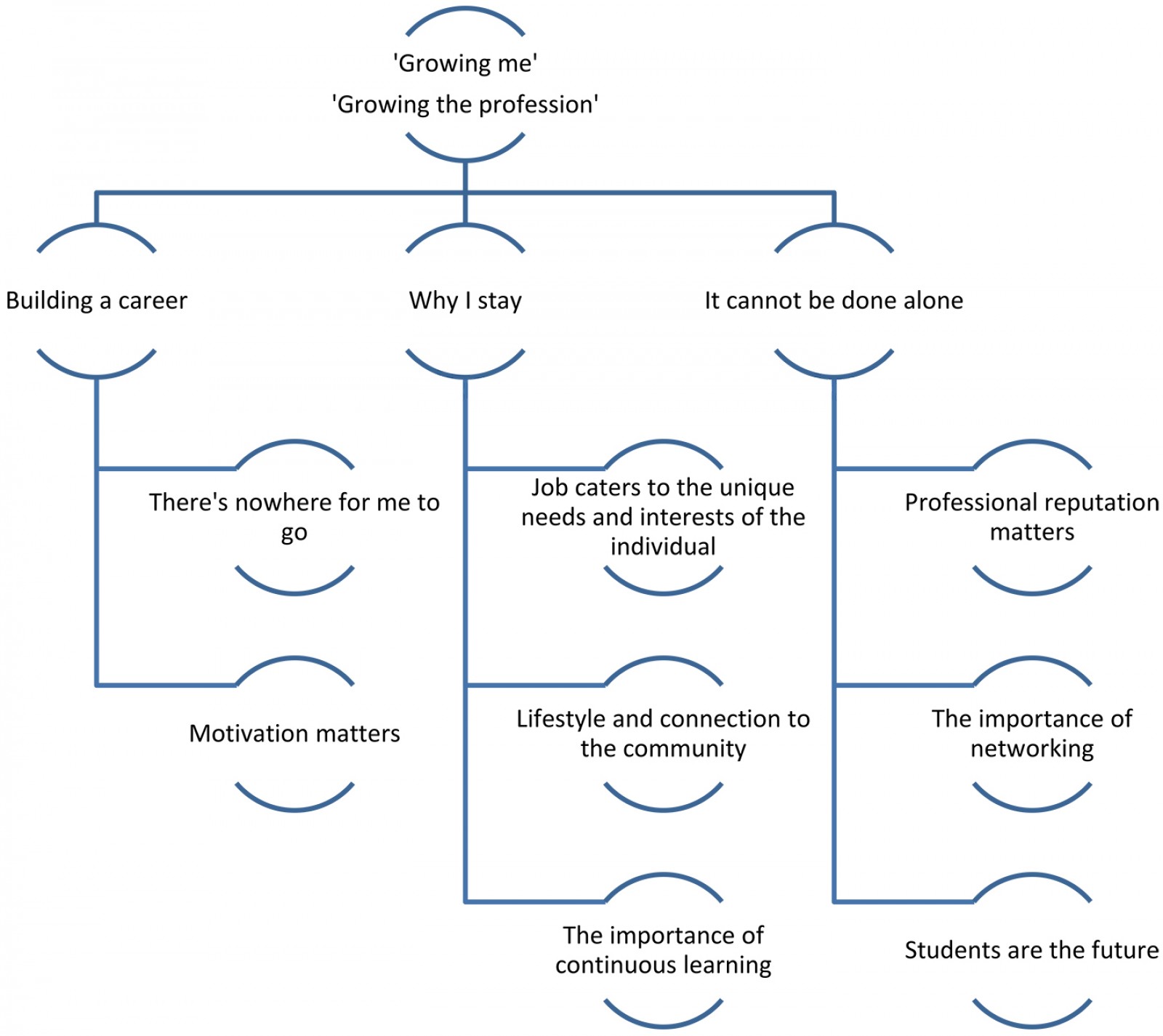

Participants from both groups provided rich responses to open-ended questions about their perceptions of rural work and initiatives considered as successful for both recruitment and retention. The overarching theme that resounded after triangulating the data was the importance of ‘growing me’ and ‘growing the profession’. Three superordinate themes were also generated: (i) building a career, (ii) why I stay, and (iii) it cannot be done alone (Fig1).

Table 1: Demographics of 11 podiatrists who participated in focus groups

Figure 1: Focus group and interview themes.

Figure 1: Focus group and interview themes.

Theme 1: Building a career

A clear theme was the importance of having opportunities to build a career for new graduates, and its potential for this to affect rural recruitment and retention. Subordinate themes included: (i) there’s nowhere for me to go, and (ii) motivation matters.

All focus group participants were concerned about job availability within their first few years of clinical work (both those working in rural locations and those working in metropolitan locations). Participants readily identified that they sought jobs in their preferred area of clinical interest (eg sports or high risk). However, when job availability was limited (eg public sector employment), they were forced to look to other settings such as the private sector, leading to exposure to working outside of a primary clinical interest.

I wanted to work in public health throughout Uni, that was my goal. I prefer working with high-risk clients and you see more of that in public health I think than the private. (P4, focus group)

Participant concerns about getting a preferred job in a specific field stemmed from a perceived lack of opportunity for career advancement in podiatry as a profession, and the ability to change clinical area of interest. For example, all participants stated a perception of difficulty in gaining future employment in the public setting if they only had experience working in a private podiatry setting. Further, participants working in public settings expressed concerns about job insecurity or advancement due to the perceived frequent changes in funding models.

Probably the lack of flexibility and funding within the department. There is just no money to make me a [next higher grade] … There are no opportunities for career progression in podiatry in [health service name] since the restructure which just happened a few weeks ago. (P8, focus group)

Stakeholder participants identified the importance of career progression as an incentive to retain employees (both rural and metropolitan), including opportunities to take on more responsibilities professionally and clinically.

You actually need to have clear pathways and the opportunity to earn more money and the opportunity to always feel like you’re always growing as a professional. (P13, phone interview)

Similarly, stakeholders all identified factors they believed lead to clinicians leaving regional or rural locations or the profession. A common finding was the impact of short-term contracts. Participants explained that employees were keen to settle in a regional or rural location, but ongoing funding was commonly tenuous.

It’s a tension. I’m sort of getting with one of my [junior staff] now. And I go, well yes, you’ve got the talent, yes, I could see you operate on that level, but I just don’t have the means at this moment in time to create a [next level] position for you. So, it’s a source of stress. (P3, phone interview)

I do think that, particularly in podiatry, especially with the government’s changing of the [funded program model], we’re really seeing that the public sector workforce is changing, and the positions are not permanent anymore and people are being locked into fixed term contracts. It’s quite a sad situation. (P4, phone interview)

Stakeholders identified the importance of understanding a clinician’s motivations behind applying for different rural positions and what they sought from the role itself.

I want to know what their reasoning is. I know they need a job, I know it’s a given that they have to earn a salary. But I want to know what makes them incentivised to want to live here specifically as opposed to competing for a position closer to home in somewhere like Melbourne. (P3, phone interview)

Theme 2: Why I stay

Focus group participants described factors that make them want to stay in a rural job and stakeholders identified initiatives seen as beneficial for retention, as matters that could be applied to rural workforce development. Subthemes included (i) job caters to the unique needs and interests of the individual, (ii) lifestyle and connection to the community, and (iii) the importance of continuous learning.

Recently graduated podiatrists working rurally valued the variety of clinical work with people who had different health needs.

It’s very broad in a regional city, you see lots of different stuff. See lots of kids from the schools, lots of sporting and the elderly of course. I guess the diversity of what we do in a regional city is a bit greater than what you’d do in a big town or larger city. (P11, focus group)

They also cherished feeling they had made a difference in the life of someone seeking their care.

… [it] made me feel like I made a difference … I really love my work. (P4, focus group)

Participants gave varied responses about working in private practice settings in rural locations, highlighting how their initial experiences shaped how they felt about remaining in the workplace.

Well I felt like I was really thrown in the deep end and I didn’t have anyone to ask questions, I didn’t have anyone to clarify anything. I had no reception help; I was pretty much running the show … (P1, focus group)

Stakeholder participants described the importance of roles catering to the unique needs of an individual. This included opportunities for flexible working arrangements to accommodate employees’ hobbies or social/family responsibilities. Ensuring the job itself kept employees interested and satisfied was considered to facilitate retention. The wide variety of rural caseload was also considered challenging, with graduates requiring skills to deal with this.

… we know that health professionals don’t necessarily get into the job for the money, it’s the skill mix and the challenge. (P8, phone interview)

Focus group participants working in both rural and metropolitan settings readily identified different lifestyle preferences affecting and driving their decisions about where to work and live. Valued attributes were having a short commute time from home to place of work, being geographically close to family and friends, flexible work hours and the ability to live with family with the purpose of saving money.

I think the flexibility to work hours, my bosses are very flexible in terms of the hours that I want to work ... (P3, focus group)

I was born and bred there; I have been there my whole life. It has been really easy, I still live with my mum and dad. I got work straight away and I was really really lucky I could stay in [regional location] with all my friends. (P7, focus group)

I guess I only would have moved if it was home. The ability to live at home has been good to save a bit of money. (P11, focus group)

Stakeholders also talked about unique lifestyle factors attractive for work in regional and rural locations. This included a more relaxed pace of life when compared to metropolitan locations, shorter commute times, and financial incentives.

More affordable housing prices is definitely an incentive. Let alone not dealing with traffic in the morning, having a more relaxed pace of life and really only being 3 hours from Melbourne should they wish to return home, or take in some of the attractions from the city. (P3, phone interview)

I know there’s a couple of guys who work down in [regional city] and they essentially do it because they can go surfing every morning. (P8, phone interview)

Stakeholders described the importance of making new employees feel welcome when starting in a new rural position by connecting them with other employees to assist integration into the broader community. This included opportunities for social interaction both within the workplace and outside of work hours, reducing the risk of isolation.

They need to feel like they’re part of a team … not only from a clinical point of view but from a supervision and delegation point of view, and also probably more of a social point of view as well. (P6, phone interview)

Stakeholders described professional isolation as a factor negatively affecting retention, specifically in rural or remote locations where the podiatrist might be the sole practitioner. High clinical demand was also reported by participants as a potential for burnout, including limited leave opportunities or fatigue due to high numbers of students on placements requiring supervision.

But, burnout’s a huge problem here. You’re seeing much more high-risk clients, we all do here. So, sometimes it’s not even the physical hours here, sometimes it’s because you might be thinking about that work at home, and that’s why you could be burning out. (P7, phone interview)

Focus group participants commonly expressed a desire for a career that was personally satisfying and had opportunities to continue to learn. This was closely linked to having a job where they felt valued, and could access support from podiatrists with greater experience, work within a multidisciplinary team and engage in professional development.

My boss is really accommodating … he is always teaching me if we have a spare moment, we have a podiatry group that meets every month with podiatrists in the area … (P5, focus group)

Stakeholder participants highlighted the importance of providing a culture of continuous learning and growth opportunities as imperative for both recruitment and retention. This included access to both structured and appropriate supervision for their position, as well as feeling supported in a broader sense through a team environment.

We provide one-on-one supervision, but we also have a really small office space in our department, and it means that we actually have a lot of informal supervision that happens as well, people can come and ask questions and it’s a very, you know, friendly workforce. (P4, phone interview)

Student placements were also identified by stakeholders as important for a workplace learning culture and enabling staff to develop non-clinical skills.

Having student placements and supporting student placements is really important in terms of fostering that learning culture but also for people to develop their supervision skills and develop some of their non-clinical skills. (P12, phone interview)

Participants also identified the importance of providing opportunities for professional development and supporting research opportunities or specific training programs relevant to job roles.

They’re very supportive of us doing research, going to conferences and basically pushing things a fair bit to extend ourselves … (P13, phone interview)

Theme 3: It cannot be done alone

The importance of building partnerships within the community, other health services, tertiary institutions, peak bodies, and government entities was identified by participants in both groups as important for both retention and recruitment of allied health clinicians, including podiatrists. Subthemes emerged, including (i) professional reputation matters, (ii) the importance of networking, and (iii) students are the future.

A novel finding was focus group participants raising concerns as to how to improve the professional reputation of podiatry in regional or rural areas and gaining more support from podiatry peak bodies to do this. Participants perceived that people with foot or ankle concerns often went to a different health professional before seeking their service.

I find in the country a lot of people would see a [other health profession] for plantar fasciitis or an acute ankle sprain. Rather than us being their first point of call. (P7, focus group)

Focus group participants felt the general public was unfamiliar with the role of a podiatrist. Furthermore, participants described a perceived stigma of being viewed as glamourised ‘pedicurists’. Participants highlighted a need to dispel public myths about training and expertise.

It’s a matter of each and every podiatrist out there trying to give a best of a service with as much knowledge, expertise that they can and that way the word of mouth and the way that podiatry is perceived will hopefully change. (P11, focus group)

The reputation of the practice or health service was identified by stakeholder participants as important for recruitment. Participants stated if an employer had a positive reputation in the community, there would be more applicants. This also extended to the health service or practice being active in the community, so the community understood podiatrists’ roles as part of the healthcare team. Participants working in public health services identified the importance of raising the profile of allied health, to ensure allied health services were considered in the implementation of new services, increasing opportunities for current employees and future funding.

One of the things which we’ve grappled with over the years … a lot of people tend to not really know what we do … I think there is a lot of work that could be done in not only the podiatry arena but raising the allied health profile in general. (P6, phone interview)

Similarly, group 2 participants also described recognition of the podiatry profession, and the generalist scope of rural podiatrists, being critically important for rural retention.

So if we look at the Rural Generalist Program that’s being offered through Queensland at the moment, I think that one of the things that’s been highlighted is this desire for recognition and much broader skills and the access to training in those regions that might be able to better equip them to deal with a broader range of issues in regional areas. (P14, phone interview)

Common statements related to the importance of connecting employees who work in similar locations. This included networking events, new graduate programs and peak bodies offering professional development events outside metropolitan locations.

One of the things we’re doing in a regional context is increasing regional partnerships and pathways, because the thing is if they’ve got that engagement, if they’ve got that support, then they’re going to stick around if they think that they’re part of something. (P6, phone interview)

That’s just something I do for the podiatrists in my region, to try to be more supportive broadly, public and private, just to get good links so that we feel like we’re part of a podiatry community, not just working in isolation all the time. (P13, phone interview)

A stakeholder identified consolidating health services into larger health networks to improve opportunities for rural podiatry career progression. Another participant discussed the effects of public and private services collaborating, to improve health outcomes for people with foot health needs. Government funding for podiatrists was also highlighted as important for both rural recruitment and retention to support professional development activities and postgraduate study.

There are groups that are State based but federally funded, like Health Workforce Queensland that run things to help with recruitment. They also have scholarships and things like that available to help people transition from being a graduate to being a practitioner, including subsidised professional development. (P15, phone interview)

Stakeholders highlighted the issue of unequal distribution of students to regional or rural locations from tertiary training institutions as problematic for future recruitment.

From what I can gather from the response is that students aren’t obligated to take placements in the likes of [regional setting] or [rural setting]. My colleague in [outer metropolitan setting] had 11 students this year and we have zero … I am quite annoyed at the fact there is a very unequal distribution of students. (P3, phone interview)

Initiatives such as providing placements for high school students or attending career nights were used by health services for future workforce promotion. Student placements were seen by all participants as very important for future recruitment. It was also a common finding that health services were more inclined to hire someone who had completed a placement at their health service over someone who had not, and new graduates were attracted to rural jobs when they had previously enjoyable clinical placements in those services.

When students tend to come here, more often than not over the years I’ve seen them come back as grade ones or new graduates, so there must be something about what we’re doing which is right, they seem to want to come back. (P6, phone interview)

Discussion

This is the first study to explore in depth the perceptions of recently graduated podiatrists regarding rural work. This study highlights many similarities between what new graduates look for and what initiatives stakeholders see as successful strategies for both recruitment and retention. Recently graduated podiatrists are likely to be attracted to rural work and retained in rural areas if they foresee opportunities for career progression in stable jobs that offer diversity of work, as well as if they have a background of training and living in rural areas. Finally, they are attracted to the rural lifestyle and roles where they can access quality professional and personal supports. Building employment models that span public and private podiatry practice opportunities in rural geographic catchments might be attractive to new graduates seeking a breadth of career options. It is also important to recognise rural generalist podiatrists for the extended scope of services they provide, while raising public awareness of the role of rural podiatrist as an essential part of the multidisciplinary rural healthcare team.

These themes align with the recent WHO global recommendations43 concerning rural workforce (including recommendations about rural background, training and professional support to increase recruitment and retention44); however, they also demand some thought as to how the podiatry profession organises itself across public, private and generalist multidisciplinary care in order to align with rural settings and thereby attract new graduates to rural areas. The Rural Health Commissioner’s Office produced advice about service integration as a means of creating attractive rural allied health positions, where podiatry full-time-equivalent roles could be shared across public and private sectors, with aggregated back-of-house administrative supports to increase service efficiency45.

Other studies, looking at occupational therapists, identify that there may be professional challenges unique to rural practice, including lack of professional support, difficulties in accessing continued professional development and limited understanding of the role of an occupational therapist25,26. In rural areas, communities may view nurses and doctors as being able to provide podiatric care, and this may be cheaper in situations where people are less inclined to hold private health insurance; however, increasing podiatric service use is likely to reduce the burden on current medical workforce shortages and increase the quality of specialist footcare advice to rural people. Mixed public and private podiatry services may be important for community members who incur cost-related barriers to podiatry service access46, and more use of podiatric services is likely to increase public awareness, particularly in rural settings where information is spread by word of mouth. Further, rural communities may not know whether they need a referral to podiatry services and may need information about how to access the services. This could be promoted through rural primary health networks.

Recent podiatry graduates sought access to strong podiatry supervision, working within a multidisciplinary team and opportunities for professional development to build a satisfying career. The need for ongoing learning and support for new rural allied health workers by more senior staff has been identified in international literature reviews and is supported by national policy advice in Australia for a supervision package to support rural allied health providers to invest time in supervision18,45. The benefits of continued professional development in rural areas are well documented as retention factors throughout the rural workforce literature44. Extending beyond improved patient care and quality assurance, continued professional development is identified in the literature as helping to enhance career development, improve morale for individual allied health professionals and produce a well-informed and motivated workforce45. This highlights the benefits of supporting continuous learning for not only the benefit of patient care but also the recruitment and retention of rural podiatrists.

Previous rural experience has been established as a well-known factor for facilitating the uptake of rural work, including a rural upbringing or undertaking a student placement in a rural location47. However, this study builds on this specifically for allied health, where the evidence is still emerging18. Stakeholders emphasised the importance of building partnerships between health services, tertiary institutions, peak bodies and government entities as fundamental for growing training and practice networks that will foster the future allied health workforce (advice from Australia’s Rural Health Commissioner’s Office in 2020)45. Previous studies call on tertiary institutions to integrate rural curriculum content to not only expose students to rural practice but also to assist in the development of specific skills to become competent rural practitioners26. This aligns with WHO global recommendations and might assist with retention where rural podiatrists are skilled to work across a range of undifferentiated rural complex caseloads.

Stakeholders highlighted a number of policy initiatives that could be applied to attract rural podiatrists, including the Rural Locum Assistance Program31, the Allied Health Rural Generalist Pathway32 and using service and learning consortia across rural and remote Australia to embed ‘grow your own’ health training systems45. Government policies are important for investing in the future rural podiatry workforce, funding enough ongoing public positions and considering their integration with private and outreach roles, to meet the foot health needs of wide geographical catchments45. Consolidation of health services in rural settings was a novel finding of this study. Stakeholders highlighted the benefits of collaboration of smaller health networks to improve opportunities for career advancement and to prevent professional isolation. It might be important for rural podiatry roles to be developed within team settings and in partnership with rural and remote communities, where longer-term contracts are possible, enable team-based care and link to community needs (therefore being both rewarding and sustainable)18.

The limitations of this study must be considered when interpretating the findings. Although these data provide an accurate reflection of the perceptions of the participants, it may not be reflective of the entire podiatry profession, including those who graduated more than 5 years ago. Similarly, this study only included participants who were practising in Australia, so the results may not be transferable to podiatrists practising in other countries. Furthermore, different data collection methods were used between the two groups, which may affect the richness of the data35.

Attitudes towards workplace experience can change over time; therefore, further research is required to understand the factors influencing recruitment and retention of podiatrists in both rural and urban settings. A mixed-method approach with longitudinal data of podiatrists would provide more comprehensive information regarding the effect of their workplace experiences and the key factors influencing workforce decision-making in their careers.

Conclusion

This study explored perceptions of recently graduated podiatrists towards working rurally at the start of their careers and the initiatives stakeholders see as successful for both recruitment and retention. This research identifies the importance of the profession organising itself and building sustainable rural jobs that meet the needs of communities and the expectations of new graduates in order to recruit and retain this group. Opportunities for rural origin students and rural podiatry training along with ongoing quality supervision and professional development are paramount to growing the rural podiatry workforce. Rural communities in Australia have complex footcare needs and specialist podiatry support could be better integrated as part of rural multidisciplinary team-based care, but this may require increased community awareness and better recognition of rural generalist podiatrists. Partnerships with the community, other health services, tertiary institutions, and government entities will be essential to address integrated solutions that foster increased access to skilled rural podiatrists.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from Australian podiatrists and podiatric surgeons for their continued contribution to the PAIGE study and assisting in its dissemination. They also acknowledge Drs Matthew McGrail and Deborah Russell for their initial support in design of Waves 1-3 PAIGE surveys.

References

Supplementary material is available on the live site https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/6930/#supplementary

You might also be interested in:

2016 - Contribution of military psychology in supporting those in rural and remote work environments