Introduction

Oral health is ‘a state of the oral and related tissues and structures that contribute positively to physical, mental, and social well-being and the enjoyment of life’s possibilities’1. Oral health during childhood significantly contributes to oral health over the lifespan: primary teeth hold spaces in which adult teeth grow, and children who have early childhood caries (ECC) often develop caries as adults2. Thus, it is crucial to support optimal oral health for all children3,4.

The oral health of Indigenous children in Canada and globally is a major public health issue. Compared to 48% of non-Indigenous Canadian children, 80% of First Nations children and 71% of Inuit children between the ages of 6 and 11 years report having experienced ECC5. Among First Nations children of other ages, ECC prevalence rates are as high as 91%6. Studies have highlighted the associations between oral health and the social determinants of health, including socioeconomic status, geographical location, and sociocultural beliefs5,6. Indigenous Peoples in Canada who live in rural and remote communities often face risk factors that increase the likelihood of experiencing oral diseases, such as the consumption of sugary drinks and processed foods, living in close quarters, having a lack of oral health knowledge, and having reduced access to dental care7.

Studies aiming to understand First Nations’ oral health perceptions have shown that health perceptions and attitudes are often community- and culture-specific, and emphasize the need for community partnerships to create effective programs to improve oral health8,9. These studies focused on adults’ perceptions and beliefs despite oral health issues also being prevalent among the young people of First Nations communities8-11. According to oral health professionals and researchers, children and youths’ understandings must also be considered to implement programs that are appropriate for their target age group9,12.

This project sought to expand upon a previous study that identified oral health barriers and facilitators in an Anishnabeg community in northern Quebec13, and examines the oral health attitudes, perceptions and experiences of children and youth in two Anishnabeg communities. The researchers specifically sought to learn how Anishnabeg children and youth experience and understand oral health through methods that promote the recognition of their voices in their own health matters.

The two Anishnabeg communities

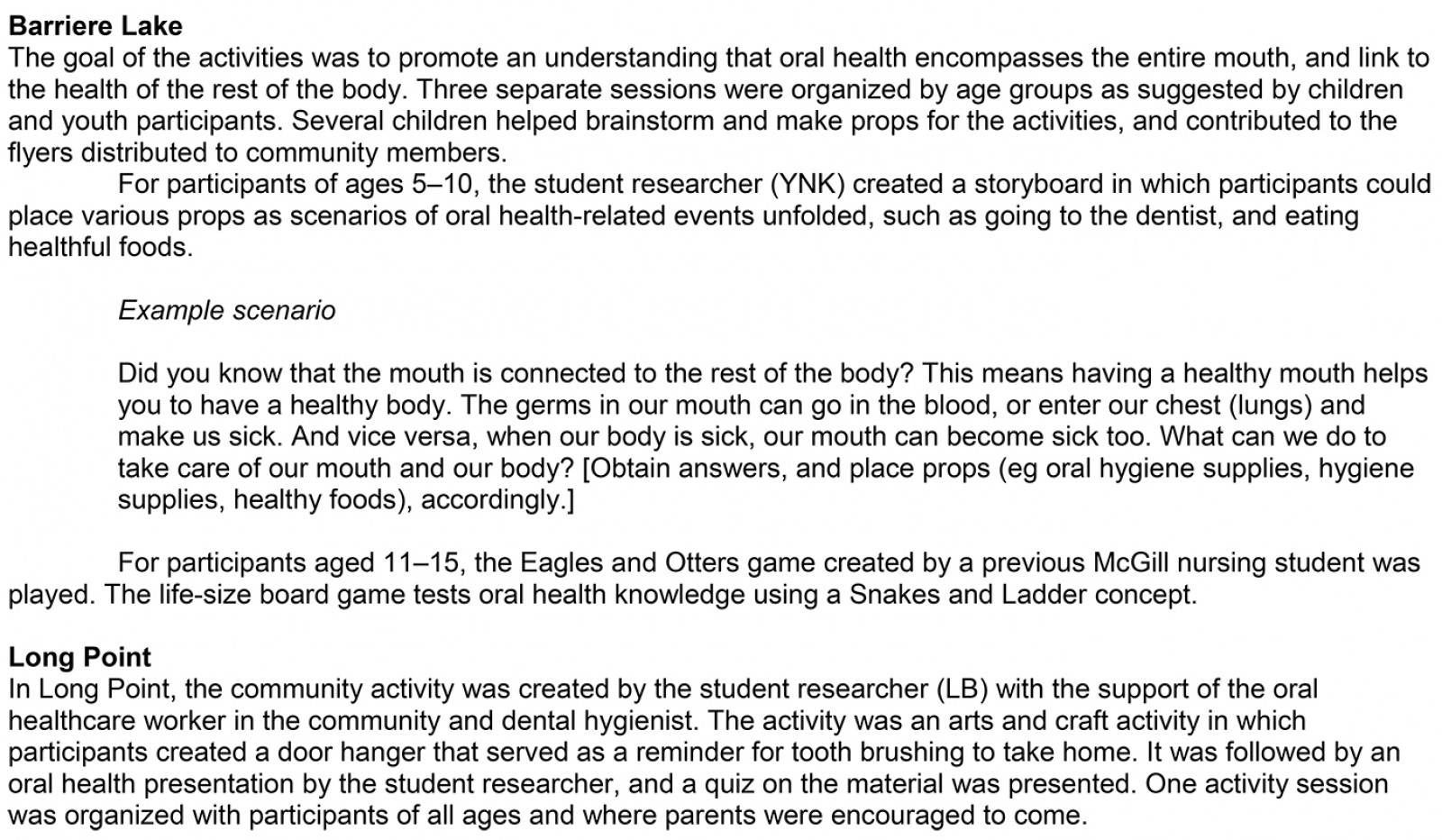

The Algonquins of Barriere Lake and the Long Point First Nation are two of nine Anishnabeg communities in northern Quebec14,15. The two communities each have their own distinct histories, local governing bodies, and services (Table 1). Both communities endeavor to maintain their traditional ways of living by teaching children the Algonquin language, hunting and trapping, and engaging in cultural activities and ceremonies. Nursing stations that are funded and partly managed by Health Canada strive to meet the communities’ health needs.

Table 1: Descriptions of community settings for two Anishnabeg communities14,15

Overview of ongoing oral health programs in the two Anishnabeg communities

The Algonquins of Barriere Lake and Long Point First Nation face reduced access to oral health services. The communities primarily receive oral health care from the Children’s Oral Health Initiative (COHI), a federal, community-based program that aims to prevent dental disease and promote oral health for First Nations children and mothers during the prenatal and postnatal periods9. As a part of COHI, the same dental hygienist visits the two communities every 4–6 weeks to provide oral health screenings, apply fluoride varnish and dental sealants, and provide counselling and workshops for families. Until 2018, COHI provided services for children aged up to 7 years; due to the need for continuity in oral health care for children, the dental hygienist started seeing all students attending elementary school in the communities. Currently, COHI has increased its age limit to include all children up to 12 years. COHI services are provided in the health clinics, at school during class hours for students, and at daycare centers. Children and youth are given kits with oral health supplies and a note from the dental hygienist that highlights specific concerns or areas for improvement (eg taking enough time to brush thoroughly, or the need for sealants). In each of the two communities, a community member is employed and trained by COHI as a COHI aide. The COHI aides provide oral health supplies and education to children and parents, and coordinate future COHI interventions with the dental hygienist.

A dentist and dental assistant had visited the community of Long Point First Nation once a week for the past decade to hold a free dental clinic open to all registered community members. This dentist has retired, and there is work in progress to form partnerships with new dentists in both communities. Schools in both communities are committed to improving their student’s oral health. In the Kitiganik Elementary School, the breakfast and lunch program for students was modified with the dental hygienist’s input to eliminate unnecessary sources of sugar (eg replacing juice and popsicles with water and yoghurt). Students in both communities brush their teeth in the morning at school, and the COHI program replenishes oral hygiene supplies to ensure this practice is ongoing. All classrooms in Kitiganik Elementary School, and students in kindergarten to grade 5 in Amos Ososwan School, strive to make brushing a daily habit.

Methods

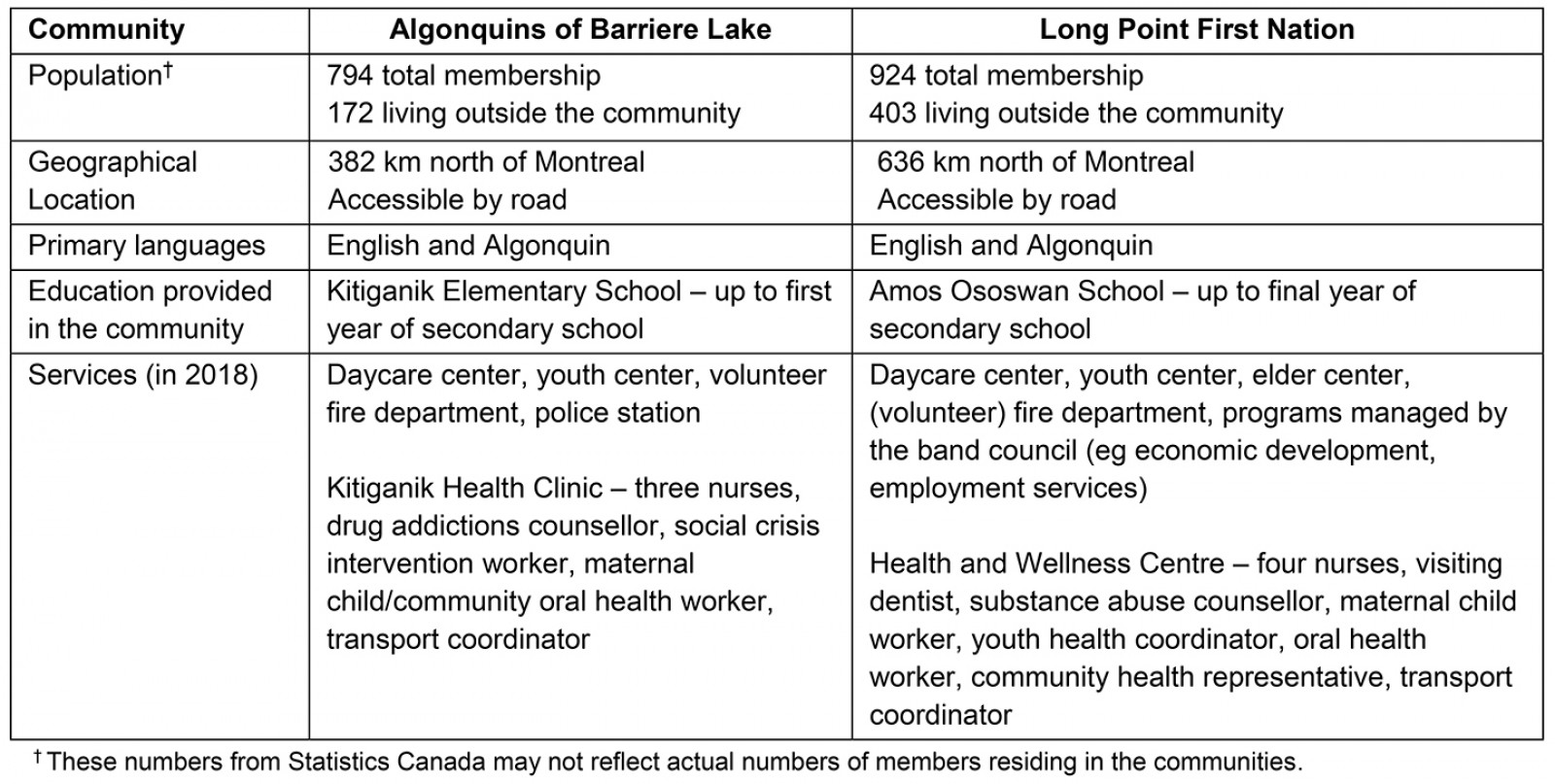

This project was conducted in 2018–2019 (Fig1) as a part of ongoing partnerships between the Kitiganik Clinic, the Health and Wellness Center, the Ingram School of Nursing, and the Views on Interdisciplinary Childhood Ethics Team (VOICE) at McGill University. The project sought to learn how Anishnabeg children and youth experience and understand oral health, and use this knowledge to help promote oral health in the communities.

Figure 1: Schematic overview of the study design.

Figure 1: Schematic overview of the study design.

Focused ethnography

Ethnography is a process through which a researcher seeks to learn from members of a cultural group to understand their worldview16. The researcher becomes immersed in the sociocultural context of the participants and uses methods, such as participant observation and in-depth interviews, to produce detail-rich descriptions of people’s experiences and sociocultural context17. Focused ethnographies examining smaller social units have been adopted in nursing research to understand how people integrate health beliefs and practices16,17. A focused ethnographic methodology was chosen for this project due to time constraints and its specific aim to understand oral health from children and youths’ perspectives.

Conceptual frameworks

Academic research with Indigenous peoples in the past focused on Western ways of knowing, and Indigenous stakeholders were often not treated as equal partners18. Researchers have been called to collaborate with Indigenous communities on research driven by communities19 and local worldviews, and thereby endeavor to ‘decolonize’ the research process20. The present study was grounded on Bartlett and colleagues’ (2007) framework for Indigenous-guided decolonizing research21. The framework prioritizes Indigenous peoples’ voices, and encourages researchers to situate themselves as co-learners21. The researchers specifically sought to frame the present study in Anishnabeg worldviews and values13,22-24, and aimed to learn about a health concern identified by the communities. The project was guided by community members, and the student researchers also invested time to build relationships with participants by engaging with the communities through concurrent nursing clinical placements.

In the present study, children are viewed as active agents who can speak about their own unique experiences, and shape their own lives and the lives of others25. Thus, the researchers sought to value and respect children and youths’ unique experiences and insights by framing the project with principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR). Through CBPR, participants are active partners in the research project, and researchers seek to generate end-products that benefit participants26. The interview questions and data analysis prioritized oral health perceptions of children and youth (eg What are some ways you take care of your mouth? Why might it be good to take care of your mouth?) rather than imposing Western and biomedical perspectives. At the conclusion of the project, presentations and group activities took place to share preliminary results and to continue oral health promotion with the children and youth.

Project design

This project consisted of interviews, participant observation, and group activities. The student researchers collected and analyzed data in consultation with McGill supervisors, onsite supervisors, and key informants.

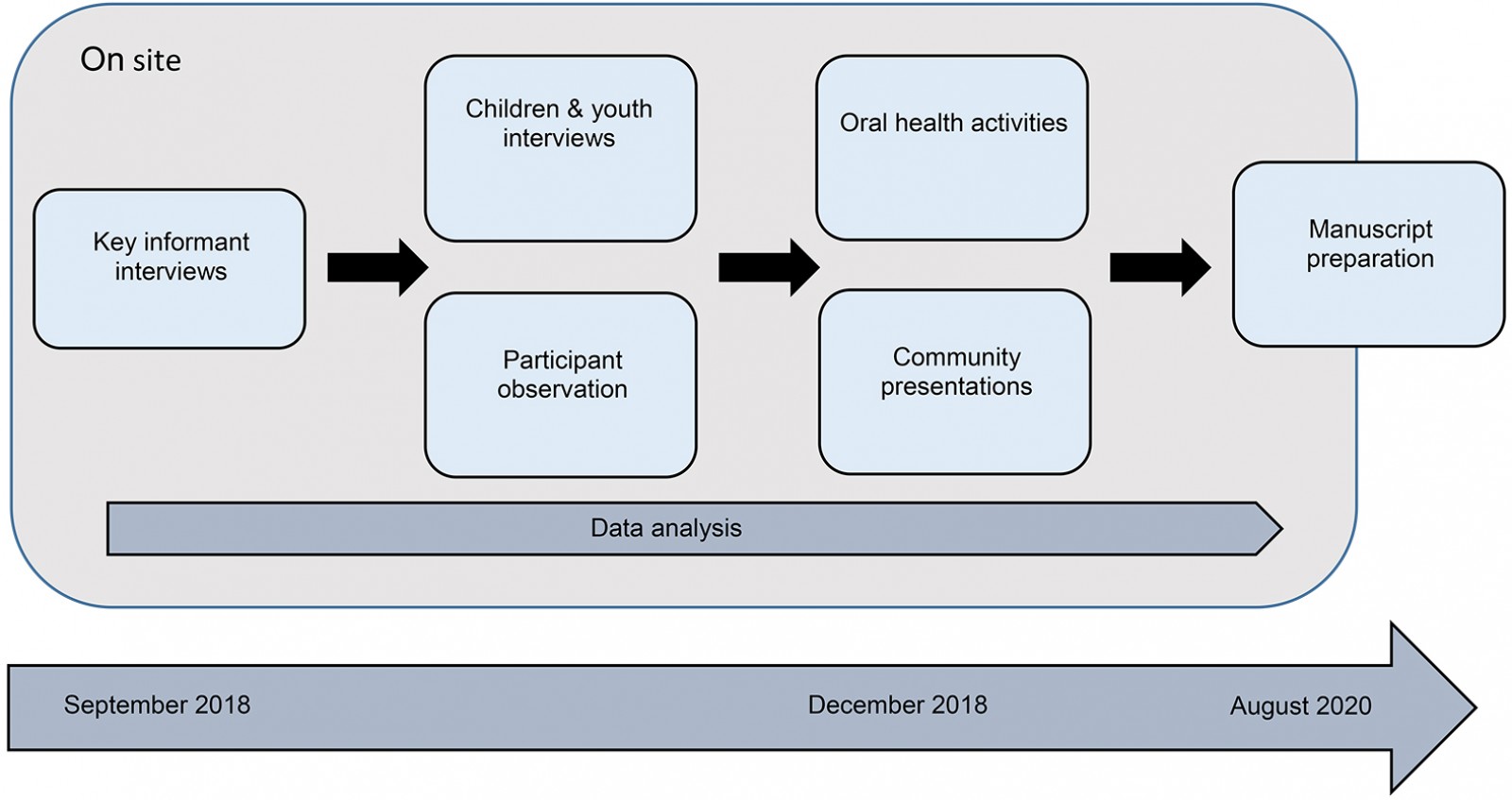

Interviews: Key informants were interviewed during the initial stages of the project to obtain a preliminary understanding of oral health in the communities, and for their input on the interview questions for children and youth. In total, 12 adults in leadership positions were recruited through purposive and snowball sampling (Table 2). All key informants were community members or those with prolonged engagement with the community through their work.

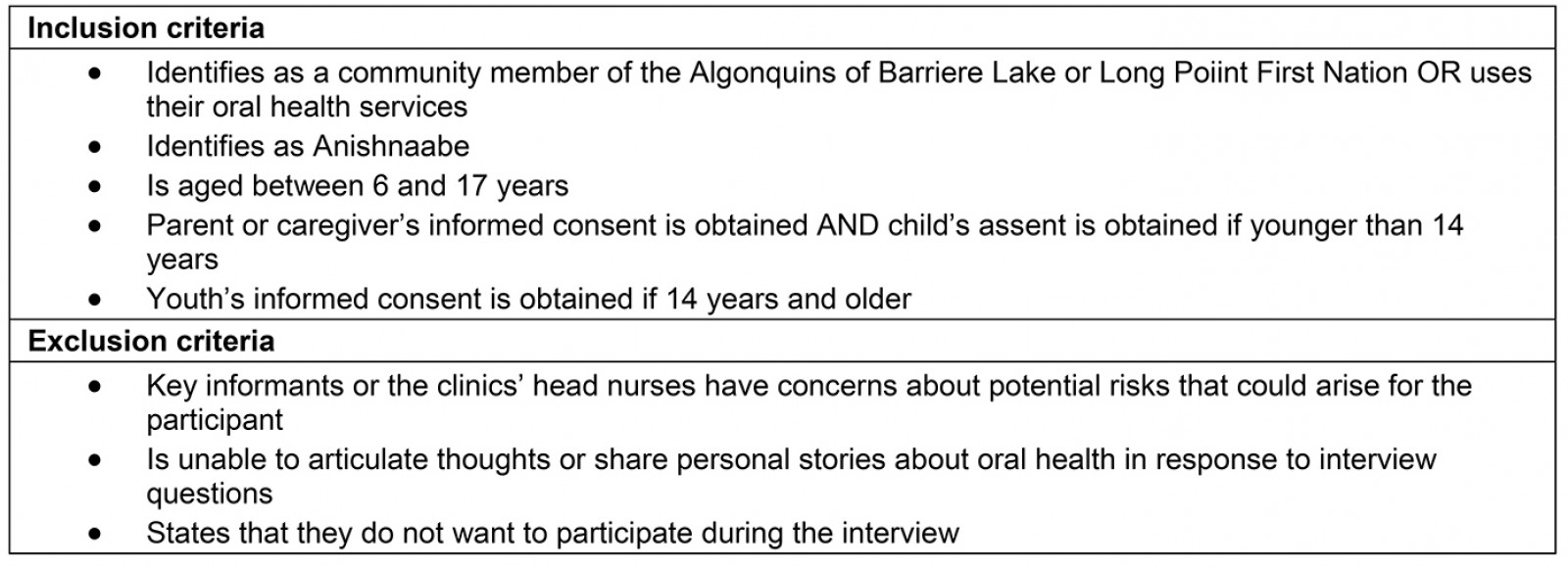

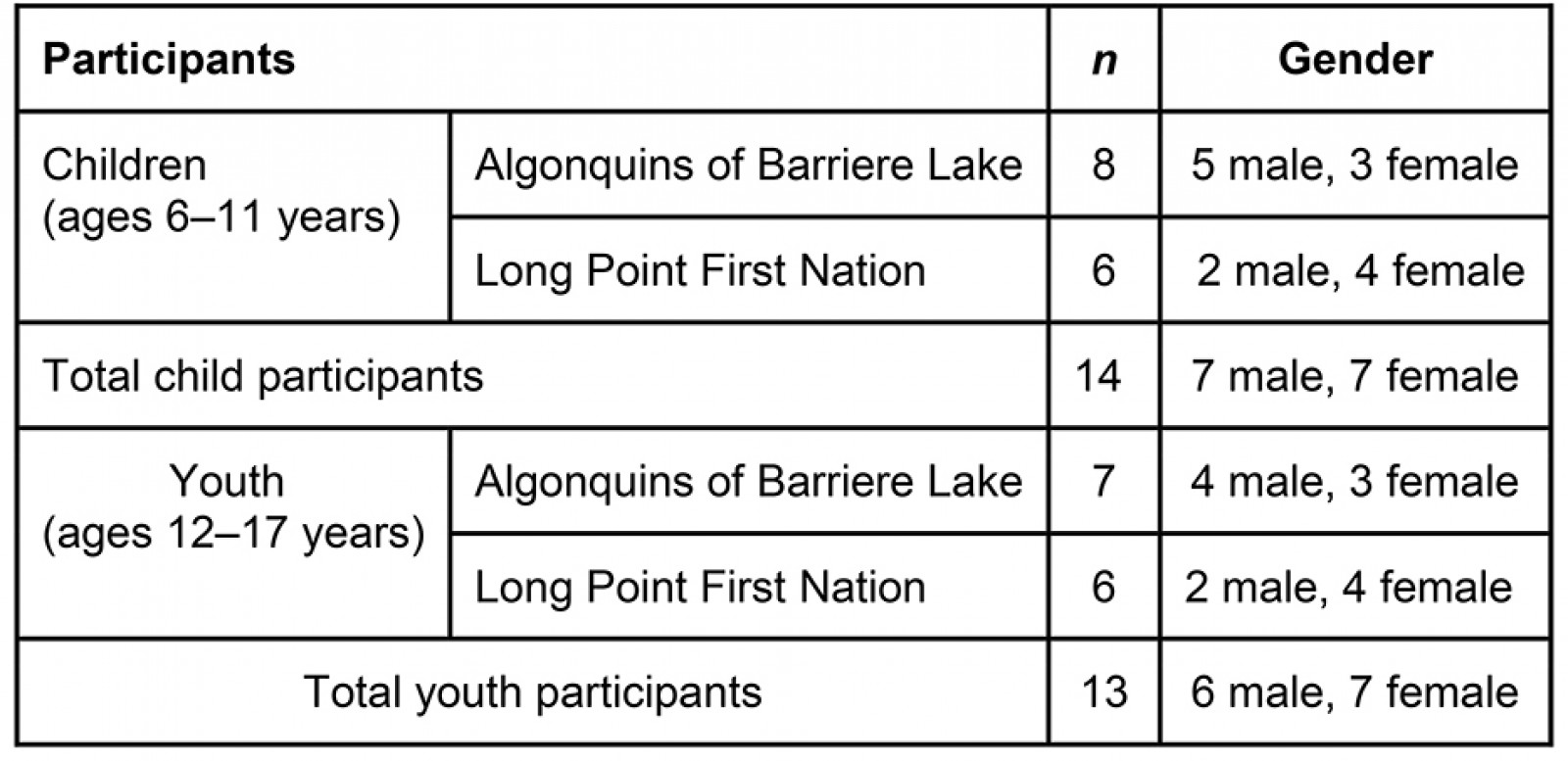

Due to the sensitive nature of non-Indigenous and non-community members conducting research with Anishnabeg children and youth, key informants were closely involved in the sampling of child and youth participants. Key informants helped establish the inclusion criteria with the purpose and nature of the project in mind, and identified potential participants for inclusion (Table 3). Effort was made to obtain a sample indicative of the communities’ young people (Table 4). Interviews with children and youth were conducted after seeking consent from their parents or caregivers, then assent or consent from the child or youth. Interviews took place in private rooms in the health clinics, the Kitiganik Elementary school nurse’s office, or at participants’ homes upon request. Interviews were audio-recorded with permission. For interviews that were not audio-recorded, the student researchers took detailed interview notes immediately following the interviews. In total, 27 children and youth participated in interviews.

Table 2: Key informant demographics

Table 3: Inclusion and exclusion criteria for interviews with children and youth

Table 4: Children and youth demographics

Participant observation: Participant observation sessions supplemented the interview data and allowed the researchers to engage informally with participants to gather rich, in-context information. Student researchers obtained consent or assent from participants, and consent from parents, oral health professionals, and school teachers when applicable. Participant observation took place in school classrooms, during dental appointments with the dental hygienist and dentist, in the waiting rooms of the clinics, and during group activities.

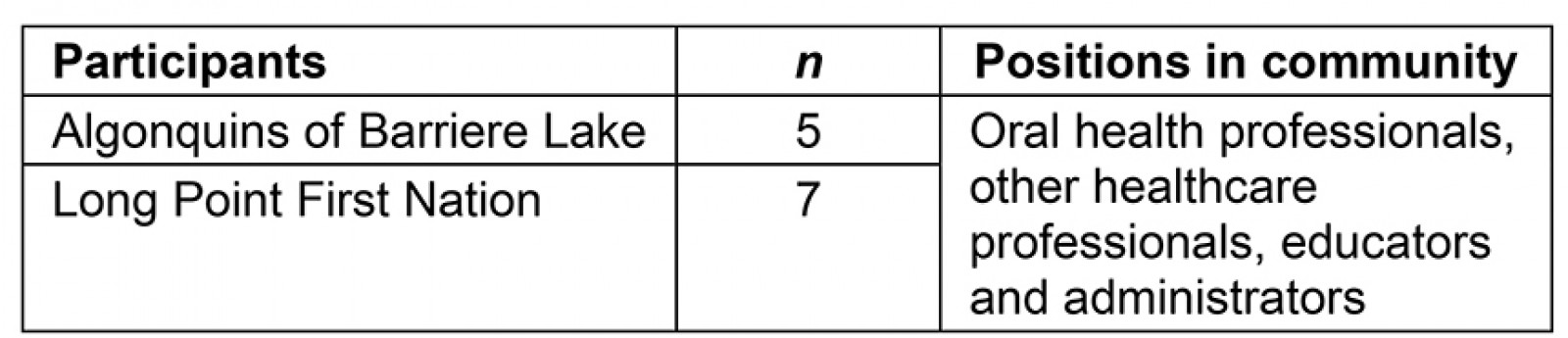

Group activities: Interactive activities open to the communities took place towards the end of the study. During interviews, children and youth gave ideas for the types of activities they wanted to have, and the activities were developed for each community based on preliminary results (Appendix I). Throughout group activities, participants were eager to answer questions and listen to peers, thereby reinforcing existing oral health knowledge, and correcting oral health misconceptions. In every session, healthy snacks such as fruit and vegetable platters, granola bars, and fruit smoothies were made together to display easy and healthy snack ideas. To conclude the activities, dental supplies were distributed as prizes.

Data analysis

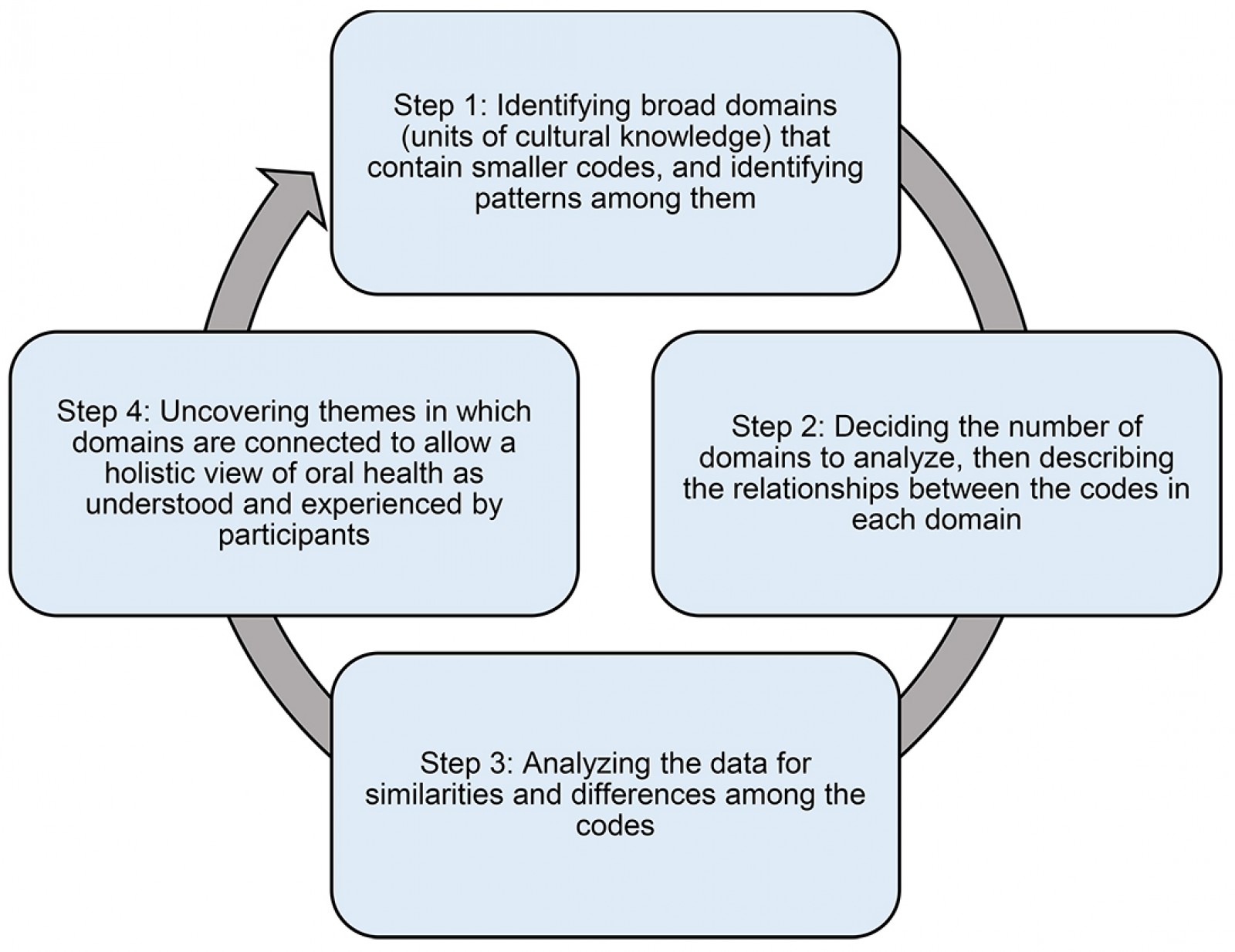

Data analysis was iterative and concurrent with data collection (Fig2). The student researchers (EB and YNK) performed a thematic analysis of interview transcripts and field notes from participant observation16. Throughout data analysis, the perspectives of children and youth participants as well as local understandings of oral health were prioritized21,25.

To ensure methodological rigor, several strategies were used: (1) the student researchers generated data from multiple sources (interviews and participant observations); (2) two additional researchers on the team at McGill University (FC and MEM) participated in iterative unfolding of the design, data analysis, and interpretation; (3) the student researchers aimed to capture experiences that were indicative of the two communities, and kept a record of demographic information about participants and research context to help ensure transferability; and (4) preliminary themes were shared with key informants throughout analysis to gain feedback and interpretation, and, towards the end of the study, group activities with students and presentations to community members allowed the student researchers to disseminate preliminary results and gain feedback16,17. Sharing preliminary themes allowed the student researchers to continue to situate themselves as co-learners and promoted the communities’ engagement at every step of the research project.

Figure 2: Data analysis.

Figure 2: Data analysis.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the McGill Institutional Review Board. The project followed principles outlined in the Tri-Council policy statement for research with First Nations, Inuit, and Metis people27, and project approval was received from the two clinics, the dental hygienist (DC), and respective schools.

Results

Five main themes were identified, which illustrate children and youths’ oral health beliefs, knowledge, and practices in the two communities.

1. Children and youth primarily describe oral health in relation to their teeth only

Children and youth construed definitions of oral health using their own experiences, and focused on the appearance of their teeth. Having good oral health meant that teeth were ‘white like paper’, and ‘clean’, whereas poor oral health meant that teeth were ‘yellow’ or ‘black’, ‘crooked’, and ‘rotten’. Although having caries was a negative experience, having caries did not necessarily mean that one had poor oral health. Rather, oral hygiene was viewed as essential for achieving oral health, with tooth brushing, flossing, and using mouthwash spoken about in every child and youth interview. Some participants also mentioned drinking water and eating fruits and vegetables to keep their mouth healthy.

When the student researchers asked participants about the link between oral health and overall health and wellbeing, only a few seemed aware of this link. Several young participants of Long Point First Nation explained that oral health affected multiple realms of their lives. One youth stated: ‘[Oral health is] really, really important. It’s not just physically but also mentally’. Children and youth who stated there was no connection between oral health and general health still discussed the effect of oral health on psychological wellbeing. Children from the Algonquins of Barriere Lake highlighted the positive and negative feelings associated with oral health experiences. One child stated that he felt ‘a little bit sad’ about having cavities, while another spoke about how brushing alleviated the worries of potential cavities: ‘[When I brush] it feels good knowing that all the cavities are starting to go’. Others reported feeling happy or relieved after a dental appointment because they knew their teeth were being looked after.

2. Motivators for maintaining oral health

For children and youth, consequences of poor oral health were key motivators for practicing oral hygiene. A participant from Long Point First Nation explained: ‘When I was young, I wasn’t too into oral health … I didn’t really know the consequences. It’s mostly the consequences that … makes you want to act’. The consequences of poor oral health discussed by children and youth included experiencing toothaches or tooth loss, and having aesthetically displeasing teeth, which in turn could negatively affect their image.

Children and youth explained that wanting to avoid pain was a powerful motivator. One youth from the Algonquins of Barriere Lake explained:

[If I don’t take care of my mouth] it’s going to hurt and I’m going to go on the same path as my brother. He has to take Orajel every night, and he cries because it hurts.

Several key informants and youth from the Algonquins of Barriere Lake recalled adults using scare tactics such as, ‘brush your teeth or else your teeth are going to look like [insert name]’s’, where the community member referred to had discolored or missing teeth. These scare tactics promoted the conceptualization of tooth brushing as a means to prevent teeth from appearing unhealthy.

Children and youth were sensitive to the effects of the aesthetics of their teeth on self-presentation. Youth and key informants mentioned that having imperfect teeth prevented people from smiling because they felt insecure about their teeth. One youth from the Algonquins of Barriere Lake shared: ‘Every time I take a picture, it’s so yellow my teeth … I don’t like the yellow teeth’, as an explanation for taking care of her teeth. Another youth described the social implications of oral health by explaining that her brothers teased each other and even physically fought about their ‘yellow teeth’.

The media and social events motivated youth to practice oral hygiene. One youth from Long Point First Nation mentioned:

The media affects a lot of the youth. You see people with perfect teeth … and then you look at yourself and you don’t have that. It kind of pushes you to brush your teeth.

Another youth from the Algonquins of Barriere Lake explained:

The most time we brush our teeth is before an event, like going to the movies, out with friends, or to check out a hockey game, so it doesn’t stink …

This comment was alluding to the impact of aesthetics of oral health during social gatherings, which motivated youth to engage in oral health behaviors.

3. Oral health tends to be put ‘on the side table’ and not highly prioritized by adults or children

Throughout the interviews, it was evident that oral health was not highly prioritized by participants. One key informant shared a belief that she said was commonly held by adults, and noted its consequences:

If you didn’t have teeth when you were younger, [people think] it’s okay for your kids to not have teeth growing up … They don’t realize they’re hurting their own kids, because [they] want to eat food but they can’t because they can’t chew, they can’t bite into it.

One youth from Long Point First Nation similarly explained that oral health is not always an immediate priority:

Forgetting [to brush is] not really a big deal … when it gets to the point when you haven’t brushed [for] a few days, it can be problematic.

Children and youth attributed cavities to eating unhealthy, but candies and junk food were still prevalent in their diets. Children often enjoyed junk food from the corner stores and during community events, and adults in the community of Algonquins of Barriere Lake were observed distributing sweets and other sugary snacks as rewards for good behavior.

As a key informant stated, oral health was ‘put on the side table’ in the face of other priorities, and financial limitations affecting families’ access to oral health materials and services. In Long Point First Nation, a young child recalled that her mother did not provide toothbrushes and toothpaste for her brother ‘because she didn’t have no money’. In some large families, parents had the challenge of prioritizing every child’s oral health equitably: a youth with eight siblings shared that she was unlikely to see the dentist soon because her parents were ‘always too busy with [her younger] siblings’.’ Health workers advised parents to bring their children to the dentist, but many parents ‘[were] too busy and they just [did not] care as much,’ according to a youth from Long Point First Nation. The dental hygienist said that parent involvement is a priority she aims to address in her work. Parental involvement was often challenged by reasons such as being unavailable when the dental hygienist was on site, and having financial limitations and priorities that competed with dental appointments outside the community.

4. Children and youth recognize parents and caregivers influence their oral health

Children and youth in the two communities had differing views on how their parents and caregivers contributed to their oral health. Most children and youth in Long Point First Nation mentioned an adult family member as being significant in instilling oral hygiene practices. One youth shared:

I think that the parents are [helpful to oral hygiene] because I probably wouldn’t have [taken] care of my teeth if my mom hadn’t told me everyday to.

This youth was explaining that her oral hygiene practices would be poor without her mother’s support.

Children and youth in the community of Algonquins of Barriere Lake recognized that parents helped with their oral hygiene when they were younger; however, they now viewed themselves as capable of maintaining their own oral health. For example, one youth replied, ‘I take care of myself, and [my parents] take care of themselves’, when describing oral hygiene practices at home. According to another youth, parents were not strict about tooth brushing:

I just go straight to bed [at night] and my mom doesn’t say anything. And [later] when she says go brush your teeth, I say I’m too tired and she lets me go to bed.

Children and youth may have minimized parents’ and caregivers’ contributions because they do not perceive parents and caregivers as strong oral health role models. One child stated that his father ate unhealthily since ‘he drinks pop everyday’, and several children described that they never saw their parents brush their teeth or were unsure if they saw the dentist.

5. Children and youth demonstrate agency in oral health

Children and youth exhibited agency in oral health in several ways, one of which included taking responsibility for practicing oral health behaviors. Many children stated they reminded themselves to brush, rather than their parents. A youth from Long Point First Nation explained that she stopped drinking pop when she learned the amount of sugar in one can, while another tried to consume small amounts of sugary foods at a time and practiced oral hygiene immediately after. Several youth participants from the Algonquins of Barriere Lake who lived and attended secondary school in another community scheduled their own medical and dental appointments.

Participants also promoted the oral health of family members and peers by reminding them to brush their teeth, and some had taught older family members how to brush properly. One child from the Algonquins of Barriere Lake shared that she tells her friends at school: ‘go brush your teeth … I’m going to be waiting outside [the bathroom]’. Student researchers also observed participants exchanging oral health information, such as the amount of toothpaste, or what the dental drill does, with dental professionals and peers, demonstrating that they have and can share detailed oral health knowledge.

When asked about the potential ways to close existing oral health gaps in the community, children and youth in Long Point First Nation volunteered various solutions. For example, one child suggested making ‘stands all around [the community to] give out toothbrushes’ in order to improve access to oral health materials. Other solutions included providing healthy snacks at school, increasing the dental hygienist’s visits, having oral health home visits, and teaching older children about oral health so they can teach the younger children. These examples demonstrate children and youths’ ability to recognize problems that affect them and respond with creative solutions.

Discussion

This study adds to the existing body of oral health literature by bringing forth Anishnabeg children and youths’ oral health experiences and understandings, which has been limited in the literature4,8,9. The participants in the present study described oral health primarily in relation to their teeth, and mentioned various motivators for practicing oral hygiene. Oral health was a recognized community issue but not always prioritized by families. Children and youth recognized contributors to their oral health and demonstrated agency in oral health.

The participants of the study focused on the appearance of the teeth and oral hygiene. Similarly, non-Indigenous children explained that the appearance and color of teeth are directly related to oral hygiene and reflect a person’s ability to engage in self-care28. While dental health is undeniably a significant component of oral health, focusing solely on the teeth may minimize oral health’s contribution to overall health and quality of life, and consequently affect children and youths’ motivation to maintain oral health practices28,29. Future strategies to improve oral health in the two communities should include increasing awareness of oral health’s connection to overall health, or integrating oral health within programs that promote general health and wellbeing.

Participants’ descriptions of oral health incorporated Minimadizuin, an Anishnabe conceptualization of health and wellbeing23. Minimadizuin involves taking care of one’s mental, emotional, spiritual, and physical aspects, and caring for one’s family and community23. For children and youth, eating healthy foods and drinking water was a prominent way of promoting oral health, and they highlighted that tooth brushing alleviated the worries of potential toothaches. Children and youth encouraged others to take care of their oral health, and even monitored peers and family brushing their teeth. Oral health interventions in the future could support the communities in better realizing that practicing oral health contributes to mental, emotional, spiritual, and physical wellbeing.

Similar to other studies in First Nations and other Indigenous communities, this study confirmed the key role of dental hygienists and local health workers in promoting oral health12,30,31. The dental hygienist and Anishnabeg oral health workers supported oral health in environments with reduced access to oral health care by assessing and educating clients outside the dental office and connecting clients to other resources30,31. Oral health interventions during school hours facilitated continuity of care by ensuring all students receive counselling. However, doing so may inadvertently decrease parents’ felt need to be involved in their children’s oral health despite parents’ involvement being crucial. Moreover, young people aged more than 7 years are typically not eligible for COHI services, but studies have highlighted that adolescence is a good time to establish or modify health-oriented behaviors28,29. It is important to find ways to encourage parents and caregivers’ involvement to promote the maintenance of positive oral health behaviors, while ensuring oral health services like COHI are accessible and available to all school-aged children.

Children and youth in this study endeavored to be active in their oral health and those of others. This agency is in contrast to research with non-Indigenous children who did not explicitly state motivators for maintaining oral hygiene practices aside from being told to do so by caregivers29. The agency participants of the present study exhibited with regards to oral health could be from students having contact with dental professionals during daily activities (eg school and community events). Dental professionals’ presence in the community may serve as consistent reminders to practice oral hygiene; this context contrasts to non-Indigenous children in other studies who are typically exposed to oral health primarily in dental offices28,29. The present child-focused study demonstrates that Anishnabeg children and youth are active agents who can affect their own health outcomes and be mobilized to bring about change in the oral health of those around them.

Despite oral health professionals’ prolonged engagement with the two communities, oral health issues persist. This reality can be attributed to several factors, many of which are tied to the social determinants of health. The Algonquins of Barriere Lake previously identified community priorities superseding oral health, such as addressing drug and alcohol use, physical and sexual abuse, and unemployment, each identified because they were seen as directly affecting health and wellbeing13. Farmer and colleagues (2017) noted that addressing barriers to health such as financial and food insecurity takes precedence over oral health for many First Nations communities31. Addressing these barriers could indirectly improve oral health by creating space for communities to begin actively addressing and prioritizing oral health.

A previous study conducted with the Algonquins of Barriere Lake found knowledge alone was not sufficient for influencing oral health behaviors13. Similarly, participants in both communities knew the harmful effects of eating sugary foods but still continued this practice. Access to healthy foods is limited due to both communities’ isolated locations, and participants were quick to identify this as hindering healthy eating. A lack of fresh produce is commonly experienced by remote communities and exacerbates oral health inequities31-33. Interventions that prioritize community-based initiatives and policies that target the social determinants of health, such as securing access to clean, fluoridated water and fresh produce, improving housing conditions, and economic growth, should be coordinated with oral health interventions to make lasting improvements13,31,34.

Strengths and limitations

The participatory approaches employed and the relationships between the two health clinics, McGill’s Ingram School of Nursing and VOICE contributed to the success of this project. The student researchers resided in the communities for 4 months, enhancing their knowledge of the communities’ health beliefs and values, and allowing ongoing dialogue with community members. Although a sample indicative of the communities’ children and youth was sought through the help of key informants, participants’ views should not be seen as representative of all young people in the communities of Algonquins of Barriere Lake and Long Point First Nation. Another limitation is that no Elders were included as key informants. Despite these limitations this study allowed for unique insights into the everyday oral health experiences and understandings of Anishnabeg children and youth.

Conclusion

This project captured the unique oral health understandings and experiences of Anishnabeg children and youth of the Algonquins of Barriere Lake and Long Point First Nation. The findings demonstrate that children and youth are active agents who promote their own oral health and are able to affect the oral health of others. In addition to their agency, the role of parents and caregivers in children and youths’ oral health was highlighted, and structural barriers such as the reduced access to fresh produce and financial insecurity were mentioned as hindering oral health. Potential future directions for the communities include continuing to empower children, youth, and adults with regards to their oral health; implementing health programs that situate oral health as a contributor to general health and wellbeing; and supporting other positive health behaviors, such as access to fresh produce.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the participation of the Algonquins of Barriere Lake and Long Point First Nation. We appreciate the contribution of participants who willingly shared their knowledge and experiences, and the support of Kitiganik Elementary School, Amos Ososwan School, communities’ health workers, and staff at Kitiganik Clinic and the Health and Wellness Center.

References

You might also be interested in:

2017 - A double whammy! New baccalaureate registered nurses' transitions into rural acute care