Introduction

Information and communication technology (ICT) can facilitate long-term care; professionals can share their ideas using ICT, leading to mutual understanding and education1. Biopsychosocial factors should be emphasized when taking care of older patients in their homes or in nursing homes2,3. This is vital as older patients can have many medical and social problems because of multimorbidity4. Various professionals are typically involved in addressing these problems to ensure effective care of older patients, including long-term care in their homes and nursing homes, so mutual understanding among different professionals is vital, especially in rural areas5,6. The construction of effective relationships among professionals can further drive the productive use of ICT7,8.

As an aging society progresses, the need for end-of-life care in nursing homes can increase. End-of-life care refers to care that is needed for people dying at home or in medical institutions. Such care requires information to be shared among different healthcare professionals3,4. ICT usage among healthcare professionals can be enhanced to mitigate potential difficulties with end-of-life care.

In end-of-life care, effective communication among family physicians and other healthcare professionals through ICT can be effective because information sharing is often needed. This may include sharing patient information as well as the family’s and facility’s ideas of how long-term care should be provided. Family medicine treats patients in various stages from various perspectives, including long-term care9,10. Therefore, family physicians have a key role in the long-termcare of their patients by collaborating with other professionals11,12. ICT can be used to record their thoughts effectively and share them among healthcare professionals. Ineffective information sharing regarding terminally ill patients may lead to inadequate care and an increase in the number of emergency transportations to hospitals13. Long-term care can be facilitated through direct calls, which can contribute to better care quality14. Reasonable outcomes of long-term care include longer duration of stay of patients in their homes or nursing homes and death while beingsurrounded by their families15,16. Thus, practical ICT usage in long-term care among family physicians and different medical professionals could improve outcomes.

As rural environments may lack healthcare resources in nursing homes and have fewer family physicians, ICT can reduce the burden on family physicians and other healthcare professionals, leading to adequate long-term care17. Through the continuous use of ICT, relationships among patients, families and healthcare professionals can be improved18. Furthermore, ICT in nursing homes can improve healthcare professionals’ understanding of a patient’s clinical course by enabling professionals to share information with each other. Acute changes in patients’ conditions can be addressed in a timely manner in nursing homes, which can decrease the number of emergency calls to physicians and transportation to hospitals. A reduction in emergency transportation can enable patients to remain in nursing homes for a longer period, which can increase the rate of end-of-life care in nursing homes. A previous study in rural settings demonstrated that the application of ICT in long-term care reduced emergency transportation by 31%19. Other rural studies suggested that sharing rural patients’ conditions among healthcare professionals can reduce healthcare professionals’ anxiety, and face-to-face communication among healthcare professionals and patients can also impact on their relationship positively20,21. In the effective use of ICT in rural settings, both onsite and remote communication are important to facilitate not only reduced emergency transportation, but also end-of-life care provided in nursing homes21,22.

Previous studies have not demonstrated changes in the number of patients who receive end-of-life care in rural nursing homes following implementation of ICT19,20,22. Nursing homes in rural areas are experiencing difficulties with long-term care because of a lack of nearby clinics and physicians and the long distances of families from nursing homes. Therefore, long-term ICT use could be effective when providing long-term care in rural nursing homes. This study investigated whether the application of ICT-based communication can reduce the rate of emergency transportations to, and death in, hospitals in rural facilities.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted in Kakeya clinic (a rural clinic) and Egaonosato Nursing Home. Kakeya clinic is located in Kakeya town, which is situated in the westernmost part of Unnan City in Shimane prefecture, Japan, and 30 km away from Unnan City Hospital, the only general hospital in the city. There are three registered family physicians and three nurses at the clinic. The family physicians work at both Unnan City Hospital and the clinic, where they visit once or twice a week. The clinic does not have beds for admission, and emergency cases are transferred to Unnan City Hospital. Egaonosato Nursing Home is located near the clinic; it can accommodate 40 dependent patients. The nursing home has 4 nurses, 32 care workers and 16 clerks. The clinic physicians are charged with the medical care of nursing home patients. Once a week, the physicians visit the nursing home and attend patients. Nursing home nurses can call the clinic whenever the patients have emergency medical symptoms18.

Application of ICT

To share patient information between the clinic and nursing home, an ICT system called Mame-net was used, which was established by the local government of Shimane prefecture in Japan. Using this system, the clinic and nursing home can share patients’ medical and care conditions, as well as acute and chronic changes in patients’ medical conditions. After posting patient information via the ICT, a computer-generated notification mail is automatically sent to all medical and care professionals involved in a patient’s care. The physicians and nurses predominately share patient information using this system. If any patient shows emergency symptoms, the nurses are required to call the physicians directly by phone, rather than use the ICT system18.

Participants

An interventional study was performed with all patients who were admitted at Egaonosato Nursing Home between 1 April 2018 and 31 March 2020. As an intervention, ICT usage started on 1 April 2019. Participants were all patients living in the rural nursing home during this period; the intervention group was defined as patients living therein after application of the ICT system and the control group as patients living therein before application of the ICT system (1 April 2018 – 31 March 2019).

Data collection

Patients’ background information was obtained from the clinic’s electronic medical records. The background information included age, sex, serum albumin concentration and renal function, dependent care level based on the Japanese long-term insurance system (stages 1–5; 1: least dependent and 5: completely dependent), medical histories and the Charlson comorbidity index calculated from medical histories23, number of medicines and history of previous admission to hospitals within the past 6 months. The ICT system data were obtained from the ICT system database. The primary outcome of this research was the number of emergency transportations to hospitals by participant group (rate of emergency transportations to hospitals) and the secondary outcome was the number of patients requiring end-of-life carein the nursing home by participant group (rate of end-of-life care in the nursing home). Regarding the conditions of ICT usage, the characteristics of the participants, frequency of use and users’ perception of ICT were measured. The ICT users’ perception regarding end-of-life care in the nursing facility was queried using a four-point Likert scale questionnaire, to determine the effectiveness and difficulties in the use of ICT and the burden of end-of-life care in their work. The questions were ‘Do you feel that ICT usage is useful in end-of-life care in nursing homes? Do you feel stress regarding end-of-life care in nursing homes? Do you feel greater burden following application of the ICT system?’

Analysis

To analyze the differences in participant characteristics and the rate of death in the nursing home and emergency transportation to hospitals between the intervention and control groups, t-tests and χ2 tests were used. The Charlson comorbidity index was categorized binomially to assess the severity of medical conditions: ≥5 or not23. The questionnaire assessing ICT users’ perceptions regarding end-of-life care was categorized binomially: a rating of greater than 2 was considered a positive response. A significance level of p<0.05 was used for all comparisons. A minimum of 40 participants were required in each group based on α=0.05, β= 0.10 (power of 90%) and a between-groups difference of 20% in the rate of end-of-life care in the nursing home. Cases with missing data were excluded from the analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR v1.50 (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University; https://www.jichi.ac.jp/saitama-sct/SaitamaHP.files/statmedEN.html), which is a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation; http://www.r-project.org)24.

Ethics approval

Participants and ICT users were informed that the data collected in this study would only be used for research purposes. Participants were also informed of the aims of this study, how data would be disclosed and their personal information protected, after which they provided written informed consent to the researchers. This study was approved by the rural City Hospital Clinical Ethics Committee (approval number 20200013).

Results

Demographic data

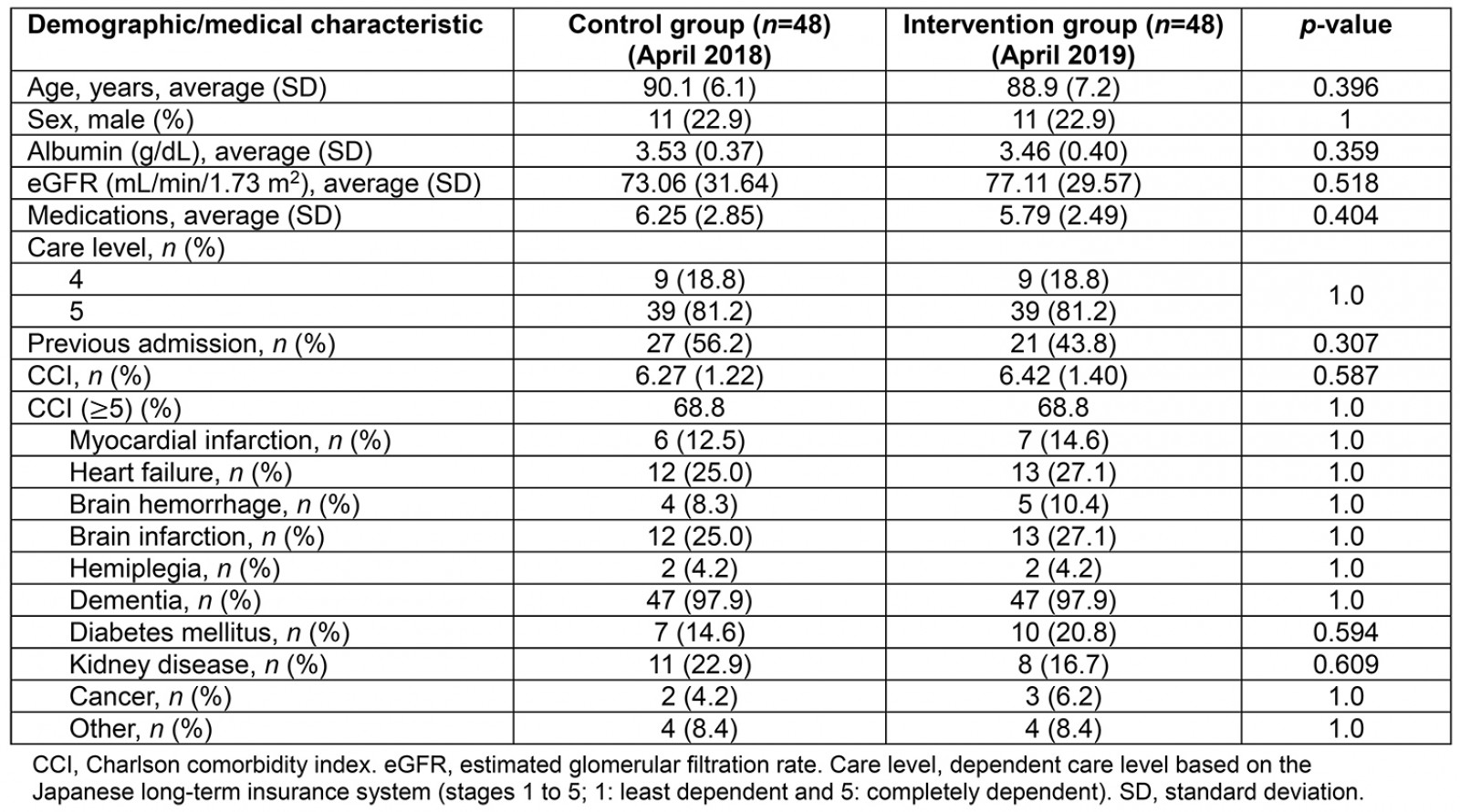

The total number of participants was 96 (48 in the ICT usage group and 48 in the control group) and the average age was 89.5 years (standard deviation = 6.7). There was no difference in the background data between the intervention and control groups (Table 1). The frequency of Charlson comorbidity index score ≥%uFF15,denoting the presence of severe medical conditions, did not differ between intervention and control groups. ICT-driven information sharing between the clinic and nursing home was performed 64 times per month, on average.

Table 1: Demographic data of nursing home participants (ICT usage and control groups)

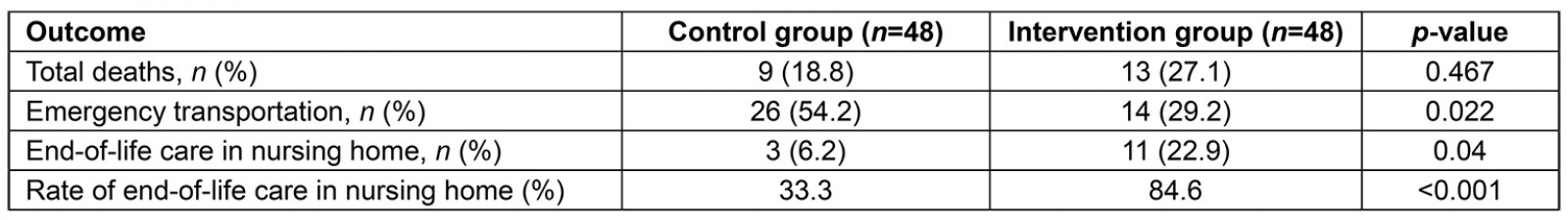

Rate of death, emergency transportation and end-of-life care in the nursing home

There is no statistical significance between the two groups regarding the number of total deaths. With respect to end-of-life care, the number of deaths in the nursing home was larger in the intervention group. The rate of emergency transportation was 54.2% (26/48) in the control group and 29.2% (14/48) in the intervention group (p=0.022). The total number of deaths was 9 (18.8%) in the control group and 13 (27.1%) in the intervention group. The rate of end-of-life care in the nursing home was 33.3% (3/9) in the control group and 84.6% (11/13) in the intervention group (p<0.001; Table 2).

Table 2: Rates of death, emergency transportation and end-of-life care nursing home participants (ICT usage and control groups) in April 2018 and April 2019

Perceptions of ICT users regarding ICT usage and the burden on their work

Data were collected by utilizing information obtained from the questionnaire, which was completed by 52 users (4 nurses, 32 care workers and 16 clerks). Of the users, 62.1% considered ICT to be effective, 45.3% felt stress regarding end-of-life care and 23.1% felt increased burden from the application of ICT to their work.

Discussion

This study revealed the effectiveness of ICT use in rural clinics and nursing homes for reduction of emergency transportation of patients from nursing homes. ICT usage can increase the effectiveness of communication in long-term care between clinic physicians and nurses in nursing homes, decrease the number of emergency transportations to hospitals and increase the number of patients who receive end-of-life care in the nursing home. Therefore, the continuous and efficient usage of ICT can reduce the burden on not only medical professionals, but also patients and their families.

The reduction in the rate of emergency transportation to hospitals can be attributed to frequent information sharing and effective usage of family physicians’ knowledge and skills through the ICT system. Older patients often have various medical problems that fall within several specialties25; therefore, physicians in one specialty experience difficulties dealing with these medical problems26. In the present study, frequent information sharing between family physicians and nursing home nurses facilitated physicians’ clinical reasoning and prepared them for the changing symptoms in patients. In addition, the clinic physicians had previous experiences in primary care within the specialty of family medicine. Differences in physicians’ specialties can affect how patients’ symptoms are approached, which can change how physicians decide a patient needs emergency transportation27,28. As family physicians can address various medical problems comprehensively, constant information sharing could drive family physicians to adopt a proactive approach toward patients, which could in turn prevent emergency transportations. Furthermore, although no statistical significance was obtained, the number and proportion of deaths in the nursing home tended to be larger than in the intervention group. It might reflect improved practice of end-of-life care in the nursing home, which was undetectable by statistical type II error.

An increase in the frequency of ICT systems usage and end-of-life care in nursing homes can improve the quality of rural medical care from the perspective of comprehensive care. Nursing homes can be considered a substitute for terminal care locations; in the former, patients can be cared for in an environment similar to their homes29. Many older people hope to be living in a nursing home when they are in terminal condition30. As society is aging and young people tend to leave rural areas, many older people must live alone and are therefore isolated30,31. Comprehensive care, as promoted by governments to engender effective care of older people in communities, can be accomplished by improving care in nursing homes32,33. End-of-life care in nursing homes should be promoted in remote and rural areas by ICT and through mutual understanding among healthcare professionals33,34. The continuous provision of ICT should be implemented in rural areas to enhance comprehensive care.

This study had several limitations. As it was performed in a single nursing home located in a Japanese rural area, the study’s setting cannot be representative of rural medicine in developing and developed countries in terms of the lack of medical resources, aging societies and isolation of older people. Future studies should investigate these constructs in other rural settings, such as remote islands or in developing countries. Another limitation pertains to the sampling method. Likely confounding factors were included in this study; however, randomization of the sampling process could further address potential confounds. Therefore, future studies should implement randomization to overcome this limitation.

Conclusion

ICT-driven nursing home care can reduce emergency transportation from nursing homes, and nursing home patients can remain longer in nursing homes without being admitted to hospitals. Therefore, these findings highlight that the continuous provision of ICT can facilitate end-of-life care in nursing homes.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants who took part in this study.

References

You might also be interested in:

2019 - Outreach specialist's use of video consultations in rural Victoria: a cross-sectional survey

2015 - Portable power supply options for positive airway pressure devices