Introduction

In primary care, chronically ill patient visits account for 80% of consultations1, and these patients use both daytime general practice and out-of-hours services more often than others2. Reasons for this increased visit frequency may include ineffective communication of guidelines around chronic disease prevention and management by healthcare providers and practitioners, as well as patients’ non-compliance with advice or adherence to prescription3.

At present, a range of integrated care practices are being developed and trialled to better meet the needs of people with chronic diseases in primary healthcare settings4. One such organisational approach is the chronic care model (CCM). This model provides an evidence-based framework for chronic care delivery by ensuring effective communications between an informed patient and a proactive practice team5. CCM includes six key interdependent components: community resources, health system support, self-management support, delivery system design, decision support and clinical information systems. The philosophy of CCM is holistic; that is, there is a requirement to review the individual biopsychosocial needs of patients, which may help to inform patient care6.

Primary care systems in Europe differ greatly in the way they deliver care; inequalities in the supply of health services between regions, as well as differences in care between urban and rural areas, have been reported in the European Social Policy Network country reports7. Traditionally, rural practitioners are based in areas of low population with limited resources, remote from specialist health services8. Their practice can involve care of patients with complex and serious illnesses who, in large urban cities, would be managed by a team of specialists9. Reducing rural–urban differences in chronic disease represents a formidable public health challenge10. Previous research shows that individuals living in rural areas experience higher rates of colon and lung cancers, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and obesity11. It is also noteworthy that rural areas have older populations than urban areas. Demographic ageing in rural areas is largely the outcome of the long-term outmigration of young adults, the in-migration of mid-life individuals who then age in place and the in-migration of pre-retired and retired adults12.

The purpose of this study was to determine the points of view of European rural general practitioners (GPs) about the implementation of a CCM in rural primary care settings across Europe, with a focus on the needs of patients, caregivers and healthcare professionals in rural areas.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study was based on a key informant survey from nine member countries of the European Rural and Isolated Practitioners Association (EURIPA). EURIPA operates under the umbrella of WONCA (World Organization of National Colleges, Academies and Academic Associations of General Practitioners/Family Physicians)

Procedure

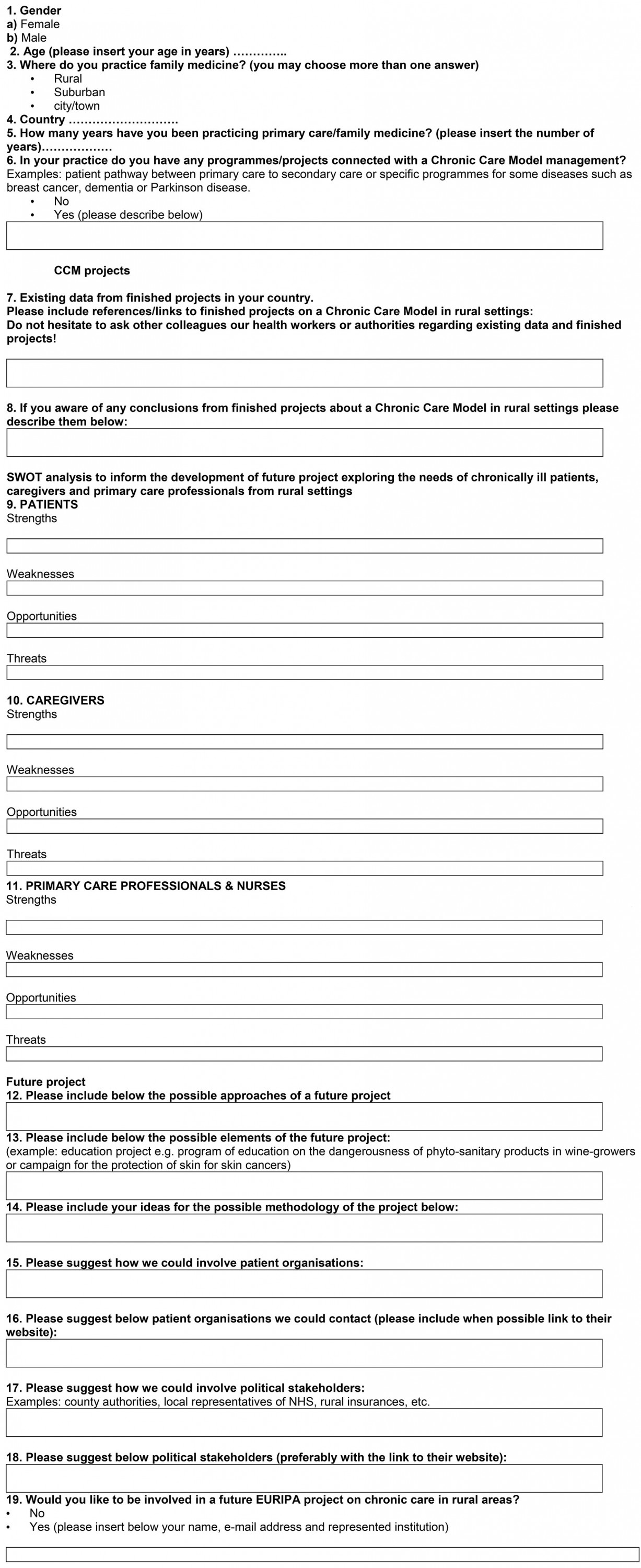

The survey was constructed by co-authors on the EURIPA International Advisory Board (DK, FP, JRS, BB, GD, KJ, AM, JAS, VT, JBK) who identified and agreed critical factors related to CCM. The structured part of the questionnaire was built on these critical factors. Open (free-text) responses to some questions were incorporated to explore issues pragmatically and at a deeper level, considering the complexity of healthcare7-9. The data were collected between May and December 2017 using the online survey tool Survey Monkey.

The authors planned thematic analysis of qualitative data and descriptive analysis of quantitative data.

Participants

GPs from nine European countries agreed to participate in this survey. A convenience sampling technique was used whereby national coordinators (DK, FP, JRS, BB, GD, KJ, AM, JAS, VT, JBK) chose informants from different geographical regions within their own country. The informants were contacted directly by the national coordinators. The informants were required to be practising primary care physicians with a good command of English, as the survey was written in English and was not translated into the national languages.

Main outcome measures

The questionnaire comprised 19 questions including sociodemographic variables, length of clinical experience, and experiences of chronic care and geographical location (Appendix I). Respondents were explicitly asked to complete a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis of CCM for patients, caregivers and healthcare professionals in rural primary care settings. The second part of the questionnaire included possible approaches to future projects and their elements, methodologies and types of involvements of the stakeholders. These factors will be analysed in a separate article.

Analyses

Preliminary analyses were conducted separately, by two authors from each of the following countries: Poland (Q1–6), Italy (Q9), Portugal (Q10) and Romania (Q11). At the end, analyses were discussed within the wider authorship team. As the qualitative responses were limited to short sentences, a brief conceptual content analysis was carried out. Codes were manually assigned and analysed, based on similar word segments and with a degree of implication allowed. For example, ‘access’ and ‘accessibility’ were coded into the same categories, and phrases such as ‘doctor/patient connection’ or ‘doctor/patient relationship’ were coded together. SWOT responses were considered by the co-authors to ensure that they had been correctly allocated within the framework, and reallocated where necessary. Pertinent quotations are included to evidence findings and are attributed by participant number.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University in Wroclaw, Poland (approval no. KB-422/2014). The participants were aware that they could withdraw at any point. Informed consent was received. Confidentiality and anonymity were assured.

Results

Participants

The sample consisted of 227 GPs (female n=117, male n=110) from nine countries: Italy (IT; n=30), Romania (RO; n=27), Czech Republic (CZ; n=26), Hungary (HU; n=26), Poland (PL; n=26), Ukraine (UA; n=26), Slovakia (SK; n=25), Turkey (TR; n=22) and Portugal (PT; n=19). The respondents’ median age was 45 years (range 22–70, interquartile range 20); median years of practice 12 (range 0–42, interquartile range 19). All respondents practised primary care in rural settings, with some also practising in cities or towns (50.22%, n=114) and suburban settings (17.18%, n=39).

SWOT analysis results

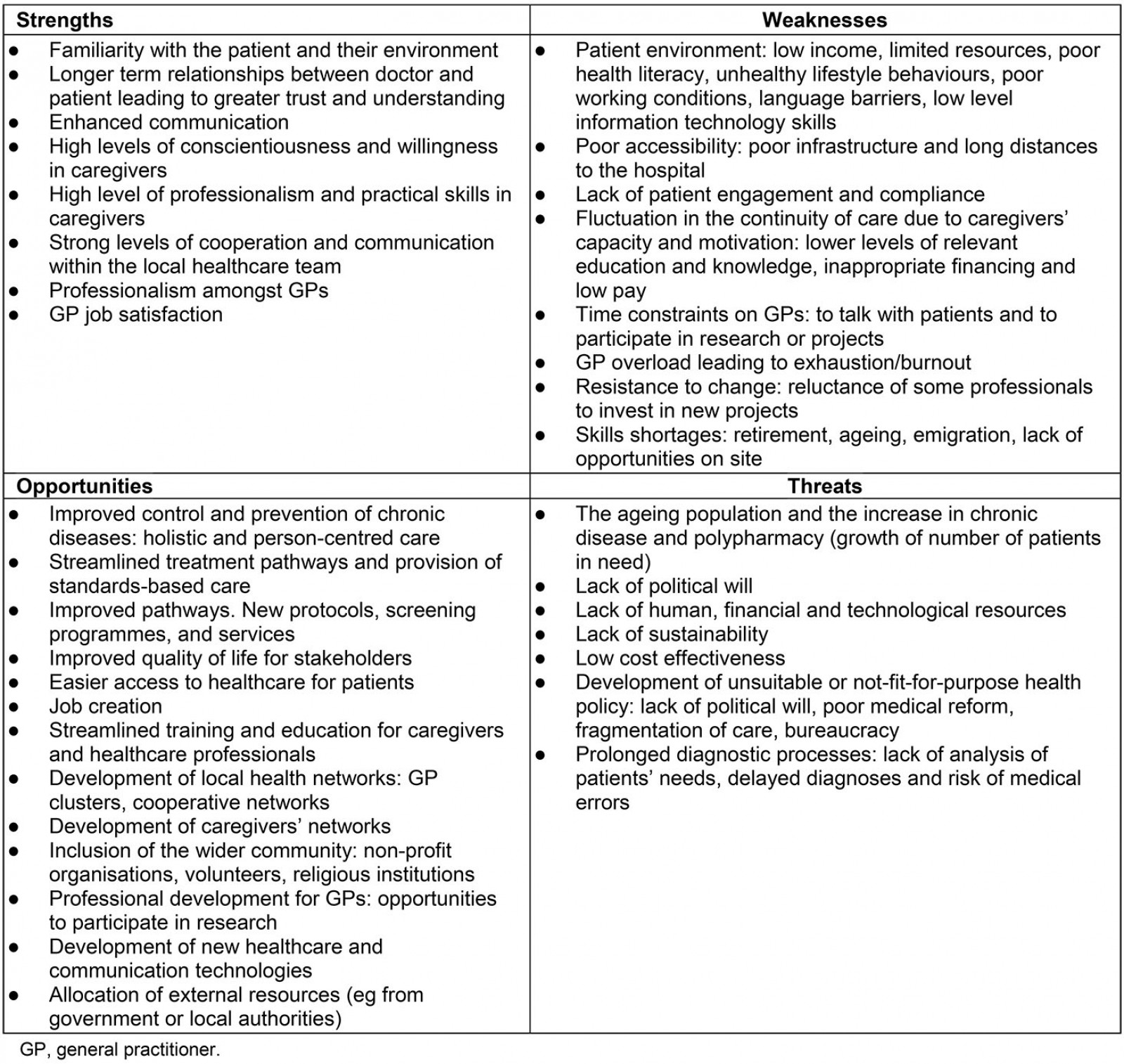

Strengths: Strengths are defined as internal capabilities of a CCM system in a rural area that would benefit healthcare performance. The main strengths perceived by GPs were professionalism, relationships and communication. The GPs considered that, in a rural community, the GP and nursing staff would have a high level of professionalism, enabling them to achieve a high standard of knowledge, qualifications and experience. Their rationale was that since professionals working in these areas do not always have close professional networks or opportunities to discuss their therapeutic decisions with others, they have to rely on their own experiences and be rigorous about continuing professional development:

Well qualified human resource (HU2)

Professional knowledge and experience (HU15)

There was also a view that there would be enhanced communication and cooperation between health and social care teams through positive working relationships and living in a close-knit community. Linked to this was the view that rurally based doctors and nurses would also benefit from a closer relationship with their patient, that they would be more familiar with each other and have a thorough understanding of their family circumstances, working conditions and living accommodation:

Better cooperation with patient, with relatives, more familiar access, better information about patients and their relatives, better anamnesis [case history] and diagnostic process (SK9)

These relationships, over the longer term, were believed to enable doctors to gather a more accurate history and symptoms, positively affecting the diagnostic and therapeutic process. For example, this would be expected to enable the detection of diseases at an earlier stage, to build a holistic vision of care for chronically ill patients, and to enable comprehensive care and the individualisation of care, better care management, better work organisation, and faster and more precise selection of the best treatment options for the patient:

Disease control. Early detection of complications (UA6, UA15)

Timely detection of the disease, proper treatment, prevention of complications (UA8)

Complex care, know-how in managing patients’ health conditions, home care (CZ5)

Holistic vision (PT14)

Knowing the needs of patients (RO7)

This ability to make a connection with their patients and to practise ‘real medicine’ (SK4), along with working in a beautiful setting, were conducive to job satisfaction and a strength of rural CCM. Respondents also suggested that the longer term relationships between professionals, patients and families could lead to a greater level of trust and mutual understanding than might be found in urban areas:

Sincerity, good relationship with doctors (SK5)

Relationships between patients and caregivers are similarly viewed as a strength, particularly in terms of the support that caregivers provide to patients. GPs perceived that caregivers’ professionalism and range of practical skills were important strengths. They understood that caregivers could and would acquire knowledge about the disease, its progression and latest methods of treatment, as well as having practical experiences from managing issues or needs on a daily basis. They suggested that caregivers would have a high level of conscientiousness and willingness to support patients, as they were likely to be ‘family’ (relatives or neighbours) rather than formally employed caregivers. Support provided by loved ones was viewed as advantageous as they understand their character and habits well. This enabled support to be better matched to the individual needs and preferences of the patient.

They are from the families of the ill person, so they know their patients and they do their work very well (SK3)

This led to an additional strength in the rural community that relates to the extent people go beyond the basic ‘necessary’ care or support and extend this to include ‘non-essential’ care and social wellbeing. GPs commented that a particular strength was the emotional connection between caregiver and patient in terms of providing love, kindness and goodwill, as well as support. The GPs surveyed suggested that having a dedicated, meticulous and effective caregiver assisted in maintaining a chronically ill patient’s condition and is often ‘better, faster, and cheaper … at home’ (RO9) than might otherwise be achieved. These findings are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Summary of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of a hypothetical chronic care model approach in rural areas across Europe

Weaknesses: Weaknesses are defined as internal factors that would negatively affect performance. The most significant weaknesses in the implementation of CCM in rural areas are aspects associated with the patient; this includes their wider environment such as their health literacy, socioeconomic circumstances, living environment, lifestyle behaviours, working conditions, language and information technology skills.

Respondents suggested that health literacy is a challenge in rural areas. Lack of knowledge about the causes and symptoms of diseases might lead patients to ignore their symptoms and mean that they only engage with a GP when the disease is significantly advanced. Health illiteracy can also cause a lack of awareness and underestimation by patients of disease-prevention activities:

They often ignore their diseases and present to health professionals in advanced stages of diseases (RO8)

This may also result in increased levels of anxiety from patients when attending appointments.

Respondents suggested that health illiteracy also extends to patients’ ability to operate health technologies, which makes them less able to make effective use of technology and electronic communication. Health illiteracy might also prevent patients’ effectively communicating with health professionals, which might lead to misunderstandings around treatment or compliance issues, and these may be misinterpreted by doctors as a lack of cooperation:

Not willing to take part or be involved, not willing to share concerns/facts/emotions related to disease (PT11)

Some doctors reported that occupational conditions such as ‘chemicals, agricultural dust, high and low temperature burden’ (SK22) and lifestyle behaviours such as ‘alcohol, tobacco, obesity’ (SK 5) could also negatively affect the implementation of CCM. Mobility and accessibility were also key. Patients often have to travel long distances between their place of residence and a health centre, and do not always have access to a car:

Long distance to high-performing medical centres; difficult transport (RO9)

Balancing workloads was seen as a huge weakness within the system and a barrier to the successful implementation of CCM. The emphasis here was on the formal social care system, which was viewed by respondents as precarious, with a shortage of workers and with those who were available often under-trained or under-educated, overworked and undervalued, with associated consequences for remuneration. Respondents commented about ‘poor salary’ (SK15, SK16), ‘low payment’ (HU23) and ‘financial shortage, poverty’ (CZ20). Similar comments about overwork and under-resourcing were mentioned in relation to healthcare professionals. Staff shortages were noted and said to be due to emigration, retirement or unwillingness to work in rural areas:

Disappearing medical offices (when they retire, there is nobody who would like to work there – in some rural places) (SK8)

Staff emigration, staff aging (PL2)

Attention was paid to the high demands placed on professionals, low staff salaries and a lack of appropriate facilities (eg lack of laboratories for conducting tests, poor facilities in medical centres):

Lack of human and technological resources (mobile phone, transport) (PT4)

The absence of laboratory and equipment (UA5)

Small salary. Problems with the staff. Lack of equipment (UA7)

Critically, doctors also commented on the lack of time they were able to spend with patients as a weakness in the adoption of a CCM system. As a consequence of these factors, respondents believed that professionals working in rural areas were at an increased risk of overwork and ‘burnout’ (CZ8, SK10, SK22). This opinion has not been elucidated further in the scope of this project, but the authors hypothesise that this happens, because in rural areas GPs usually work longer hours compared with their urban counterparts and there is no space for further activities13,14. Concerns were also raised by respondents around staff morale and their potential willingness to engage in new projects and embrace change. They also noted the effects that these issues could have on the continuity of care during implementation of CCM.

Weaknesses are summarised in Table 1.

Opportunities: Opportunities are defined as new initiatives that could be generated by the implementation of CCM in rural areas. The principal opportunity perceived by respondents was the improved control and prevention of chronic disease in patients, using a new holistic and person-centred model. For the respondents, the introduction of CCM is synonymous with a proactive approach to disease comprising improved awareness and greater responsibility for personal health:

Improvements in the quality of healthcare, improvements in quality of life (HU24)

Health education, develop self-management tactics (RO27)

Proactive in disease (SK14)

Responsibility for their own health (HU15)

Respondents believed that the introduction of CCM would assist patients to improve their knowledge and management of their own diseases.

Similarly, they believed that CCM would be a chance for patients to gain better access to medical care, medical information and treatment. Respondents mentioned the possibility of novel and streamlined treatment pathways and the provision of standards-based care. This could lead to the development of new work processes including protocols, screening programs and new services. One opportunity was that of gaining access to a doctor in different ways than visiting them, for example gaining medical advice by phone:

Access to medical information, investigation and treatment (RO15)

The ability to call a doctor by phone (UA25)

The respondents also perceived that the CCM would bring benefits by consolidating family health units into a primary care network, which would facilitate cooperation with external professional organisations. This enhanced network system would ultimately allow easier access and progress for patients along the treatment pathway.

Alongside these improvements, respondents saw job opportunities, including the chance to create a new caring profession, with opportunities for people in terms of employment and social prestige:

It is an opportunity for unemployed people (SK7)

Doctors from Ukraine and the Czech Republic also commented that the CCM model has the potential to offer caregivers a chance to improve their professional competence by participating in training and networking, both with other caregivers and other stakeholders, for example non-profit organisations, volunteers, religious institutions and others:

Deepening cooperation between individual social service providers and other partners, from both the non-profit and the public sector (CZ18)

Similarly, respondents described the potential for professional development in rural areas, including the opportunity to participate in scientific research, or join professional networks such as GP clusters:

Participation of practitioners in research (PL13)

Continuous improvement of skills (UA17)

Opportunities for the development of new healthcare and communication technologies were noted and believed to offer an opportunity for higher quality patient experiences. New technologies were thought to offer healthcare professionals an easier way of consulting and sharing experiences:

Web networks, sharing ideas, questions and research with peers from different settings (PT15)

Finally, respondents also saw opportunities for increased investment and the allocation of external resources, for example from the government or local authorities. The opportunities described are summarised in Table 1.

Threats: Threats are factors that could harm the performance of the CCM system in a rural area. Respondents considered the main external threat to successful performance of the CCM to be the ageing population and the increase in the number of people with chronic disease and polypharmacy. They considered that a growth in patients with multiple needs would equate to a growth in requirements for human, financial and technological resources and that this might pose a threat to the health of patients. Doctors were concerned that they might not have the appropriate resources or equipment to perform procedures or make accurate diagnoses, and the consequences of that would be ‘mistakes in care’ (CZ2):

Inappropriate financing. Long waiting lists for outpatient services, inappropriate capacity (HU 24)

Late diagnoses from not enough information about diseases (SK4)

There were also concerns that the ‘political environment’ (RO1) could pose a threat to the implementation of CCM through the development of unsuitable or not-fit-for-purpose health policies, and changing political priorities with service and funding implications:

Missing unified political will, lack of vision, very rapidly changing expectations (HU12)

Closure of social services (UA6, UA7, UA9, UA14)

The administration, evaluation and implementation of CCM was also considered a threat to its success, particularly in terms of cost-effectiveness, bureaucracy and fragmentation of care. Respondents perceived that the implementation of CCM might be a challenge and suggested that changing healthcare policy activities using limited or subjective data, without a full understanding of the reality of healthcare professionals’ work in the countryside, would be risky. The threats of a hypothetical CCM approach are summarised in Table 1.

Discussion

In this study the main strengths perceived by GPs were professionalism, relationships and communication. The cooperation between health and social care teams through positive working relationships was seen as a great opportunity. The longer term relationships between professionals, patients and families could lead to a greater level of trust and mutual understanding than might be found in urban areas. Other authors have indicated that communication and relationships developed over a long time between patients and physicians can have a positive impact (eg in patient care, patient adherence to treatment, holistic understanding of multi-morbidities or some other aspect of care)15; in addition, positive working relationships between patients and community health workers or primary care nurses are an important component of the multidisciplinary team effectiveness16,17. In general, promotion of a multidisciplinary approach is seen as a positive outcome of CCM18. Other opportunities of CCM described include greater involvement of nurses in the care of chronic patients: ‘program tailored to region needs’; ‘commitment to follow guidelines’7,19. In the present study, relationships between patients and caregivers were similarly viewed as a strength, particularly in terms of the support that caregivers provide to patients. GPs perceived that caregivers’ professionalism and range of practical skills were important strengths. The respondents also conceived that the CCM would bring benefits by consolidating family health units into a primary care network, which would facilitate cooperation with external professional organisations. This enhanced network system would ultimately allow easier access and progress for patients along the treatment pathway.

Alongside these improvements, respondents saw job opportunities, including the chance to create a new caring profession with opportunities for people in terms of employment and social prestige. Similarly, respondents described the potential for professional development in rural areas, including the opportunity to participate in scientific research or join professional networks, such as GP clusters. Opportunities for the development of new healthcare and communication technologies were noted and believed to offer an opportunity for higher quality patient experiences. New technologies were thought to offer healthcare professionals an easier way of consulting and sharing experiences. This must be put in the context that broadband and access to mobile technologies varies and in some rural settings the quality of service is poor. This aligns with the literature where change can be seen as a revitalising activity; some authors describe enthusiasm for care improvement20 along with career promotion opportunities and skill development21.

Patients’ health literacy, socioeconomic circumstances, living environment, language and information technology skills are the most significant barriers to the implementation of CCM in rural areas. Lack of knowledge about the causes and symptoms of diseases might lead patients to ignore their symptoms and mean that they only engage with a GP when a disease is significantly advanced. Health illiteracy can also cause a lack of awareness and underestimation by patients of disease prevention activities, and these may be misinterpreted by doctors as a lack of cooperation22. Other authors, however, think that CCM could be seen as an opportunity because the patient is screened by healthcare staff before seeing physician and there is a structured assessment in patient education15.

In the present study, workload was considered a barrier to the successful implementation of CCM, especially when there was a shortage of health personnel, or they were overworked and undervalued. Data from literature confirms that staff turnover is often a big issue and that many GPs complain that unions are unsupportive. Clinicians are sensitive to workload and time commitments20. In a Belgian mixed-methods study in which the authors assessed the degree of implementation of CCM, along with the facilitators and barriers they encountered, the intervention was felt to be too complex; it targeted different components, resulting in too many priorities19.

In the present study, staff shortages were noted and said to be due to emigration, retirement or unwillingness to work in rural areas. This project has shown that the professionals working in rural areas in the nine countries in this study are at an increased risk of overwork and burnout. Concerns were also raised by respondents around staff morale and their potential willingness to engage in new projects and embrace change. This supports the findings of Hroscikoski et al, who noted that staff in five clinics undergoing multiple care process changes struggled with change fatigue and apathy23. Regarding burnout, Graber et al found staff morale and burnout reduction associated with reports of improved care outcomes21. The main threat in the present study to successful performance of the CCM was considered to be the ageing population and thus the increase in the number of people with chronic disease and polypharmacy. Time constraints and inadequate time to work on intervention have been consistently cited as one of the main barriers to implementation of a CCM, as screening all patients is considered time consuming15, and the increase in administrative tasks is perceived as increasing workload19. Low staff salaries and a lack of appropriate facilities were seen as a problem by respondents. This is in line with the lack of reimbursement strategy and lack of financial resources shown by Nutting et al20, and further studies conducted in Belgium19. Furthermore, software very often did not meet goals, and there are sometimes hidden and unexpected implementation expenditures7.

Lack of staff expertise in a team approach to implementation has been consistently shown in the literature, and smaller organisations are the ones that face the most difficulties in addressing these barriers20. In the present study, respondents were concerned about the lack of resources and equipment to perform the procedures involved in CCM. The development of unsuitable or not-fit-for-purpose health policies was another concern and was noted by Sunaert et al, who described the poor organisation of primary care in their region19. The administration of CCM was also considered a potential threat, particularly in terms of bureaucracy and fragmentation of care. Difficulty with patient registry was confirmed, along with the need for technical support7. Mobility and accessibility were also key factors in the present survey. Patients often must travel long distances from their place of residence to a health centre, to access specialist care, and do not always have access to a car, which is typical for rural areas.

This SWOT analysis was conducted to illustrate factors that GPs perceived might affect the implementation of a CCM in rural primary care settings. Obtaining the views of more than 200 doctors (key informants) from nine European countries is considered a strength of this research. A systematic review conducted in 2015 identified multiple barriers and facilitators of implementing the CCM across various primary care settings24. The main emerging issues were those related to the internal structure of the organisation, the implementation process, and the characteristics of the individual healthcare providers – among them, the culture of the organisation; its structural characteristics, networks and communication, the climate of implementation and promptness; the support leadership and the attitudes and beliefs of the suppliers.

Rural communities across Europe are often presented as a homogenous group when in fact there are likely to be differences between countries and within countries. Specific challenges facing different rural settings are complex, including for example the distinct nature of rural primary care, as mentioned in the present project and the relationship to secondary care, but also factors such as transport infrastructure, geography and population density. Having said that, there are common characteristics, opportunities and problems in European primary care that justify this survey.

Major assets of the current health systems include the calibre, training and effectiveness of healthcare staff, as well as the likely strength of relationships and communications within and between staff, patients and caregivers in rural areas. While the quality of relationships and communication was very much in evidence, it is essential that policymakers ensure that rural practices are adequately staffed and skilled to prevent professional burnout and ensure that patients receive appropriate care. This requires political will as well as human, financial and technological resource allocation. The level of health education and literacy suggested by doctors in this study is not evident in all of the members of their communities. Respondents suggest that educating patients and caregivers and improving their health literacy would be critical to the success of a CCM in rural communities. In terms of delivery system design and clinical information systems, respondents suggested that healthcare policymakers will need to think holistically about systems to ensure sustainability and efficacy, as well as addressing their concerns around bureaucracy, further fragmentation of care and avoiding the introduction of errors in diagnostic processes.

Given that this study drew on perceptions of rural GPs from nine European countries, the authors are confident that this study will be useful for European health policymakers to implement CCMs that consider the peculiarities and priorities of rural care, characteristics that have been neglected far too often in past decades.

Limitations

A survey with open-ended questions was used rather than conducting in-depth interviews with doctors. Although this enabled access to a wider breadth of responses from a sample of European GPs, the format ultimately reduced the depth of the data available and constrained the analyses. Although this data from doctors on the implementation of CCM was comprehensive, the authors recognise that the viewpoints of other stakeholders across the healthcare system would have been beneficial. The short questionnaire was developed in a multistep process and refined after a first pilot study. Yet, it was not validated against other measures apart from a face validation procedure. The authors cannot rule out the possibility of confounding or alternative explanations to the results since the survey responses show subjective points of view.

In future research it will be worth paying attention to the in-depth information about the role of the third sector/NGOs in dovetailing with the CCM and thus helping to alleviate many of the identified challenges. Often through, for instance, day centres or lunch clubs they have ready access to these patients and may even refer patients to healthcare workers. In available publications it is not clear how that relationship plays out in the CCM model. The concept of social prescribing is also important as it involves the third sector in providing non-clinical support to people25.

In the current project, patients were not included in the study, but it is suggested that engaging with patients in future studies would be important. This would help to understand what influences patient choice in addressing health and wellbeing issues in the context of chronic ill health. In rural areas it is important to understand factors affecting access to services, physically but also in terms of social and cultural constraints, such as social class, education, poverty and deprivation as well as stigma and confidentiality.

Conclusion

Rural doctors believe that CCM would have benefits for individual patients, caregivers and/or social care professionals but that these benefits would need to be balanced against potential resource and cost implications. Ensuring adequate staffing levels and staff competency are issues that would need to be addressed promptly during implementation of CCM in rural settings. Improving health literacy among patients and their carers will be essential to ensure their full participation in the implementation of a successful CCM. Further research will need to be conducted to understand how the potential pitfalls of such a system could be addressed before its widespread implementation.

References

You might also be interested in:

2009 - Challenges faced in implementation of a telehealth enabled chronic wound care system