Introduction

Working as a physician in rural areas has proved to be challenging due to various factors including long distances, feelings of isolation, fewer professional development opportunities, weather challenges and a lack of system coordination1-4. These challenges may affect emergency medicine in rural and remote areas, both in the working conditions of emergency medical physicians and in the outcome of the patients living in rural areas4,5, where patient mortality may be higher than in urban areas5,6. One study showed that rural physicians found ways to bypass problems by creating their own medical backup system and by finding creative solutions to transportation issues4. A sparsely populated area in Sweden is defined as an area where a person has to drive for 45 minutes to reach the closest town of more than 3000 inhabitants7. One such sparsely populated area is Storuman municipality in the inland part of Västerbotten in Southern Lappland. The region of Västerbotten is pioneering in the field of rural medical research, development and innovation, and in 2014 they became a forerunner in rural research by founding the Centre for Rural Medicine8. There are no hospitals in Storuman municipality – only smaller medical clinics or cottage hospitals, in seven towns in the region9. Cottage hospitals are unique to the sparsely populated rural inland areas of Northern Sweden10. They function as general medical clinics and first-response medical centres. Several healthcare professionals are working at these cottage hospitals: physicians, district nurses, registered nurses, physical therapists and occupational therapists. There is also a mother-and-child healthcare centre. Each cottage hospital is equipped with a small laboratory and an x-ray machine, and there is an ambulance service and a smaller emergency unit that is open continuously9. To the authors’ knowledge, no published literature has described physicians’ experiences working in emergency medicine in rural Sweden.

The aim of this study was to elucidate the experiences of physicians working in an emergency medical setting in a rural area in Northern Sweden using qualitative semi-structured interviews.

Methods

Study design

This qualitative study was approached with a phenomenological–hermeneutic perspective employing an interpretive lens to explore the lived experiences of the physicians working in a rural area. Semi-structured, one-to-one interviews were completed to this end. In principle, as three of the authors are physicians working at a university hospital in a larger Danish city, it is acknowledged that the perspectives and positions of those three authors could influence the study. However, the first author (NMSH) is a medical student originating from Northern Sweden and one of the other authors (EF) works and lives in this very northern part of Sweden, so all authors think that perspectives, opinions and positions are balanced. Furthermore, combining a phenomenological approach with a hermeneutic approach allowed authors to recognise and articulate their positions during the research period. Frequent meetings involving all authors were conducted to discuss the positions and preunderstandings. It was hypothesised that rural physicians would describe challenges and obstacles in their daily work.

Study context

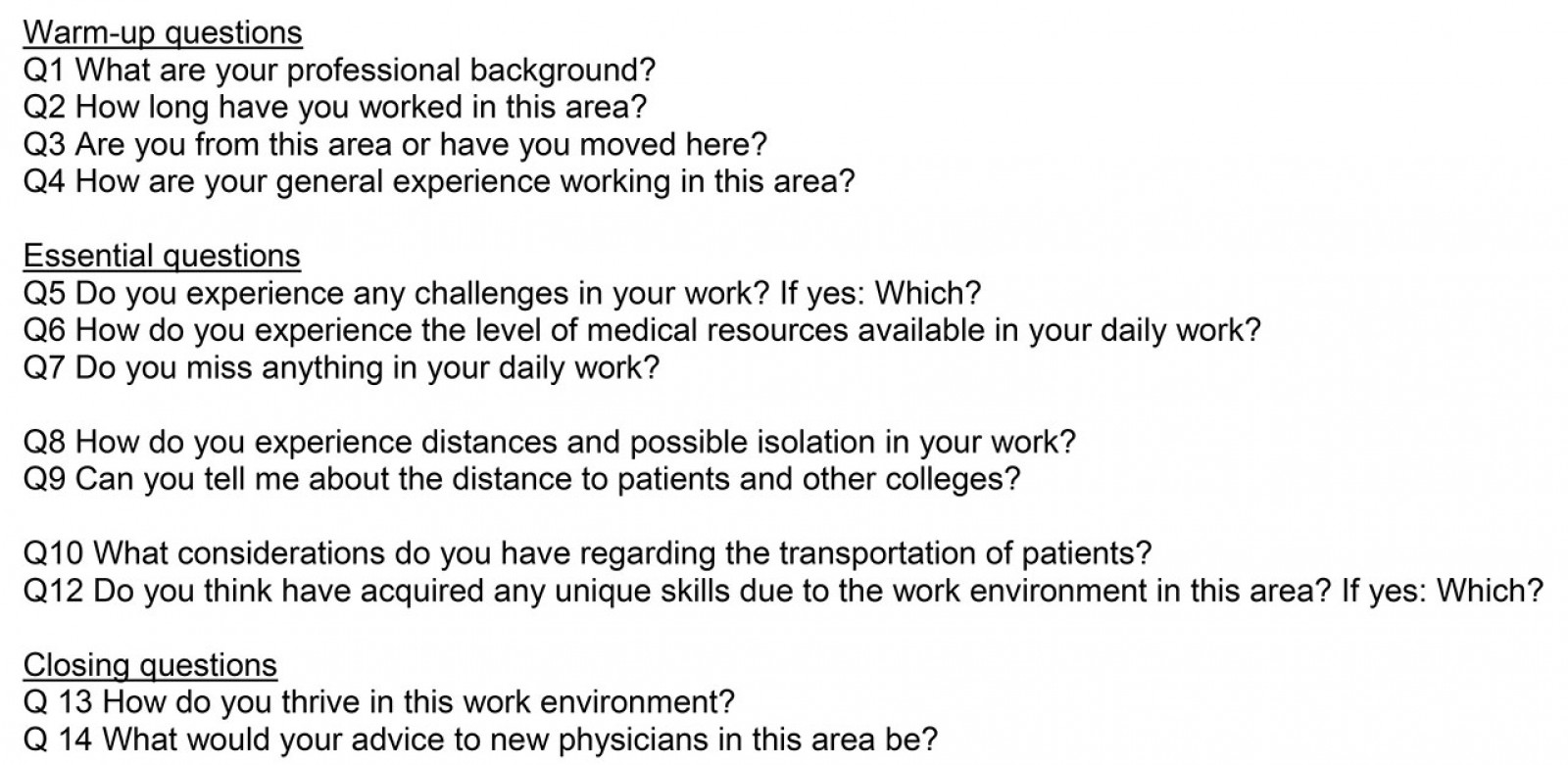

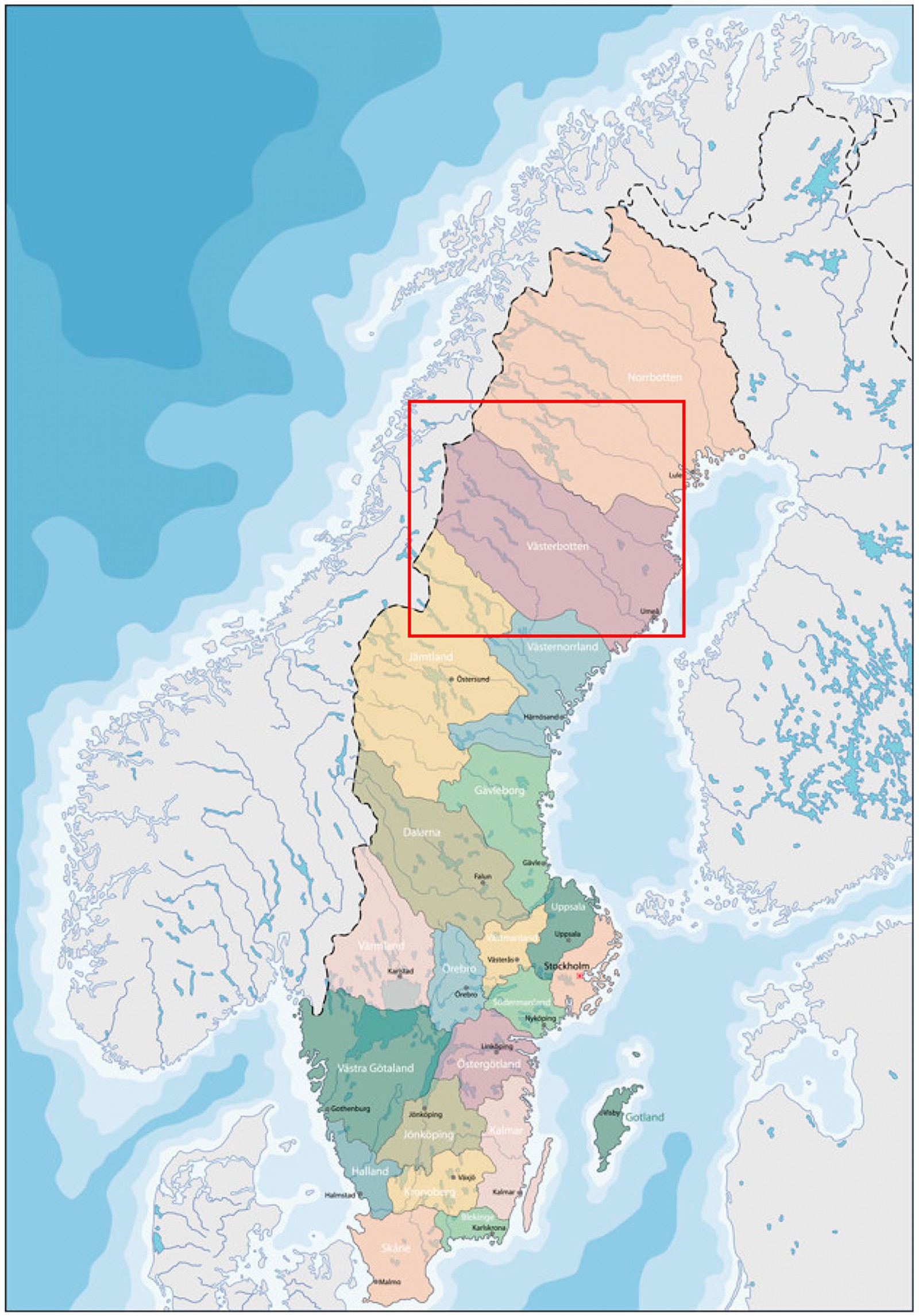

Storuman municipality has two cottage hospitals providing primary and secondary levels of health care. One is located in the mountain area in Tärnaby and the other in the small town of Storuman (2200 inhabitants). Both cottage hospitals in Storuman municipality refer their patients to Lycksele hospital. Lycksele hospital is an emergency hospital strategically placed in the centre of the region of Västerbotten (Figs1,2). It is one of the region’s three emergency hospitals, with a catchment area of approximately 40 000 km2 and servicing approximately 40 000 inhabitants. Lycksele hospital has approximately 600 employees and 80 patient beds, and is a tertiary-level care facility. It provides emergency and obstetric delivery care as well as intensive care, orthopaedic surgery (including prosthetic hip surgery), general surgery, bariatric surgery and various internal medicine specialities. There are also ophthalmological, paediatric and psychiatric outpatient clinics. The hospital has a well-developed pre-hospital emergency care unit with highly trained and experienced personnel due to the vast catchment area. The regional ambulance helicopter is located at Lycksele hospital and performs more than 500 assignments a year. The physician may refer patients to Norrlands University hospital in Umeå if a patient’s treatment needs exceed the capabilities at Lycksele hospital. Storuman cottage hospital is located 100 km away from the hospital in Lycksele, and Tärnaby cottage hospital is 229 km away from Lycksele hospital7. Forty-five healthcare professionals are employed at Storuman cottage hospital in total. Of these, three specialists and three residents are permanently employed physicians. Storuman cottage hospital services 4600 registered patients. Tärnaby cottage hospital has a patient list of 1600 registered patients. Fifteen healthcare professionals are employed at Tärnaby cottage hospital. Of these, two specialists and one resident are permanently employed physicians. At least one physician is permanently on duty in Tärnaby while three or four physicians are on duty in Storuman during the day. The cottage hospitals have an emergency ward staffed with nurses day and night. This enables them to keep patients overnight for observation or treatment. Tärnaby cottage hospital has the capacity for two emergency ward beds and Storuman cottage hospital has eight emergency ward beds. Additional patients are referred to Lycksele hospital whenever the maximum capacity is reached. Some patients living on the outskirts in the municipality and close to the Norwegian border have to travel up to 300 km to receive hospital care7. On 1 October 2020, an on-call system for physicians changed in Southern Lappland, meaning physicians at Storuman and another local cottage hospital, the Vilhelmina cottage hospital, were covering the entirety of Southern Lappland during evenings and weekends. With the exception of Lycksele municipality, only one physician-on-call covers the entirety of Southern Lappland at night. This means that, in some instances, a physician not present with the patient may supervise patient care through video chat with a nurse and the patient11.

Figure 1: Map of Sweden. The region of Västerbotten is marked with a red square.

Figure 1: Map of Sweden. The region of Västerbotten is marked with a red square.

Figure 2: Map of the municipalities in Västerbotten divided into healthcare regions. Cottage hospitals are located in Tärnaby, Sorsele, Storuman, Malå, Vilhelmina, Dorotea and Åsele. Hospitals are located in Lycksele, Skellefteå and Umeå.

Figure 2: Map of the municipalities in Västerbotten divided into healthcare regions. Cottage hospitals are located in Tärnaby, Sorsele, Storuman, Malå, Vilhelmina, Dorotea and Åsele. Hospitals are located in Lycksele, Skellefteå and Umeå.

Data collection

An interview guide was constructed according to the method of Kvale et al12. The guide consisted of questions based on the existing literature on the subject. The following topics were explored further: medical resources, feelings of being alone, absence of medical backup, transportation and medical education. The interview guide consisted of warm-up questions, essential questions and concluding questions. By using a semi-structured interview guide, explorative and probing questions could be asked when encountering new topics. (See Appendix I for the translated interview guide.) All the interviews were audio-recorded. The interviews were conducted in Swedish, allowing for the greatest degree of detail when analysing the data. Quotes from the interview that were included in the results were then translated to English.

The author NMSH participated in the daily clinical work at Storuman cottage hospital for 4 months. During this time, author NMSH made unstructured observations of the environment and had informal interviews and conversations with various physicians, nurses, physical therapists and other staff members. The information gathered in this process was used as field notes in accordance with the literature13,14.

Participants

Physicians working permanently at both Tärnaby and Storuman cottage hospitals were eligible for inclusion. Through purposive sampling, residents and consultants were included in the study and interns and substitute physicians working for only 1 or 2 weeks at a time were excluded in order to ensure lived experiences from physicians working full-time in the area. The notion was that physicians in temporary positions might not have gained in-depth experiences or would not have the same understanding of working in a rural area compared to physicians with full-time employment in the area. In total, the author NMSH obtained six recorded semi-structured interviews. At Tärnaby cottage hospital, the author NMSH interviewed two specialists and one resident. All three were living and working in the area. Three specialists were interviewed in Storuman. Two of them were living and working in the area. Two residents at Storuman cottage hospital were scheduled for interviews but, due to lack of time, they were not formally interviewed. Instead, they were part of member check of the synthesised analysed data giving feedback to the findings in the study15. Additional quotes from these physicians were included in the study due to their deep insights and knowledge of the topics.

Data management and analysis

All six interviews were transcribed verbatim with help of a secretary. Analyses of the interviews were performed using the systematic text condensation method16. The analysis process followed four steps, including reading through all of the interviews to get a general sense of the content and reading through the text for a second time creating ‘meaning units’16, then going through all the meaning units sorting them into categories and, lastly, synthesising all the meaning units to form statements regarding the participants’ experiences.

The analysis process used a combined inductive and deductive approach drawing on the theoretical model by Kolhatkar et al, who described the complexity of factors influencing the rural experience of emergency medical physicians4, but at the same time remaining open to new themes if they were identified in the process. Hence, the results were divided into four categories: (1) the close working relationships with the closest referral centre, Lycksele hospital, (2) the continuing medical education system and the specialised rural residency program, (3) the physicians’ adaptability to the rural environment and problem-solving attitude and (4) having a relatively functional transport system. A member check including two physicians from the same study setting was performed after the analysis process was completed. The two physicians at Storuman cottage hospital listened to the content and provided feedback and insight into the material, ensuring the authenticity of the results. The study followed the guidelines and standards for qualitative research established by Malterud17.

Ethics approval

Before the interviews, written permission was obtained from the chief of the two cottage hospitals to interview the physicians during their working hours. Subsequently, the eligible participants were asked to fill out a written consent form stating that they were informed about the project and would allow recording of audio. To preserve anonymity, a schematic overview of the participants could not be created. The study followed the Swedish ethical guidelines according to the law (2003:460) of ethical trials on studies involving humans18. This study was exempt from ethics approval according to Swedish legislation.

Results

The rural physicians described working in an overall thriving environment. All study participants reported enjoying their work. In particular, they enjoyed the variety in seeing and following up patients in a general practitioner’s (GP’s) office as well as handling the emergency medical part, with the entire range of emergencies, from minor to life-threatening injuries. Besides variety with emergency medical and non-emergency clinical work, the participants expressed pleasure in manual work, for instance treating fractures, performing minor surgeries and performing ultrasonic examinations.

I started working here as a young physician, and I have enjoyed the emergency medical aspect of the work. I have liked the serious emergencies, but also the common aspects of emergency care like fractures and wounds, where you can work with your hands and do things. That has been nice.

There was a notion among physicians working in the area that despite the general satisfaction regarding the work, some previous colleagues had found it impossible to thrive in the rural conditions because of factors not related to their work. These former colleagues had cited factors such as distances to friends and family and the diminished opportunities for spare time activities other than those related to enjoyment of nature.

Close working relationship with Lycksele hospital

All participants in the study reported that cooperation and communication with Lycksele hospital was a tremendous asset aiding their everyday work and in medical emergencies. The specialists working at Lycksele hospital are very familiar with the geographic distances between them and the seven cottage hospitals they service. This understanding of the rural aspects was in contrast to the cooperation physicians experienced when consulting specialist at Norrlands University Hospital in Umeå. Here, they often needed to remind their colleagues about the distances some patients had to travel to see a specialist, and they had to coordinate logistics so that a patient’s appointments in Umeå were arranged on the same trip.

Those who work in Lycksele, they know the distances and our conditions, and that is often a relief. It is often much worse when you call Umeå where you can talk to a physician that doesn’t even know where the village is located.

The personal working relationship was another reason believed to contribute to the good working relationship with Lycksele hospital. Residents at the cottage hospitals had acquired personal working relations with colleagues working at Lycksele hospital during their internship, hospital rotations and their residency as rural GPs. Most physicians working at the rural cottage hospitals lived and worked in the same environment, and they had worked together in Lycksele during their internship and their residency program. There were daily interactions between the rural GPs working in Southern Lappland and the specialists on call at Lycksele hospital for consultations.

It is an advantage that we know each other. We know the hospital physicians in Lycksele, for example, 80% of our patients are referred there. We know each other so if I call and say that now you have to be prepared, they will be, they usually never question that.

Continuing medical education system and specialised rural residency program

Most physicians in this study had the experience that the most severe medical emergencies were rare. Thus, it could be difficult to maintain the emergency medical skills over time. Many of them pointed out the need for refreshing emergency medical skills through regular hands-on training. The yearly meetings held by the Swedish Society for Rural Medicine provided opportunities for the specialists to meet, share experiences and train together.

The interns and residents working in the rural areas have structured learning opportunities, mainly due to the Rural Medical General Practitioners Residency Program created in 2010 at Storuman cottage hospital. It was invented to equip GP residents with knowledge essential for working in a rural area. As one participant pointed out, the area now reaps the fruits of that investment, as most of the GP residents working in Southern Lappland are participants in this custom-made residency program.

That is why we created the Rural Medical General Practitioners Residency Program, so that they can learn and practice to make those decisions and it is about ten years ago now. Among the young physicians, we have trained ourselves. [The knowledge and competence in rural medicine] is very good … they are very competent and learn a lot and practice a lot of things you wouldn’t do if you were a GP resident in the city.

Many of the participants expressed both a need to and a responsibility for the individual physician to refresh emergency medical skills and protocols on their own before coming to work at the cottage hospital. The participants expressed the need to train with the team at the cottage hospitals. However, some physicians expressed concerns about the frequency of the team training sessions and wished for scheduled training sessions more frequently. At the same time, they acknowledged that they did not work in a hospital, and therefore were not expected to maintain hospital-level requirements.

We have practiced a few times since I came here, and that was only short rehearsals. We have gone through the equipment in the emergency room … but we don’t have … you should have a yearly circle of trainings, [in] even years we practice these four things once a quarter, and [in] odd years we practice these things. Some things one should practice once a quarter every year, like for example unconscious patient, both adult and child.

Physicians’ adaptability to the rural environment, and problem-solving attitudes

Another factor for thriving was rural physicians’ ability to find ways to solve problems and be solution oriented. The participants were highly inclined to fix things in order to help the patient, even if they lacked the proper qualifications in the area. This was everything from solving medical needs to organise for someone to take care of a patient’s pet if the patient was admitted to the hospital. It was described how the rural reality of having a limited number of hands was solved by working outside the normative professional role as a physician and stepping in to give the nurses practical assistance in medical emergencies to get the job done.

At the emergency room in the hospital, I would never ask a physician with responsibility to help out and cut off clothes or insert a urine catheter and such. That is automatically done by the nurses, but here you are needed and before I can examine the patient and do ABCD … I often do nurse’s tasks in the emergency room and it is an advantage that one feels comfortable with inserting cannulas or at least knows how to do a capillary CRP [C-reactive protein], not all physicians know how to do that, but it facilitates the work a lot.

An unfiltered intake of emergency patients would undoubtedly require a great knowledge of both hands-on skills and theoretical understanding, suggesting that rural physicians face high requirements and expectations. Though it might be fulfilling and exciting, it raises questions about the level of stress rural physicians must be under at times, and whether all physicians can handle this pressure. Many of the participants described that they knew they had to handle the uncertainty of a reality where anything can happen, and that they might be the only physician on site. Should this physician be a junior physician, however, he or she could cope with this uncertainty by calling a senior physician. Many pointed out that they rarely felt alone because they always knew whom to call. This became easier to handle with increasing experience in the field. It seemed comforting for many of the physicians to know that they did their best. They acknowledged that, if they were not there, no physician would have been attending them.

If a child dies or is seriously injured, that is the hardest for me personally, but then it’s good to know that you have done what you can, and you cannot require more. We have the resources we have, but if we did not do what we could, then nothing would have happened, so that is the alternative.

Having a relatively well functioning transport system

This study show that a factor for creating a thriving environment was having a well-functioning transport system, although many of the study participants emphasised that the considerations they made in advance of transportation of a patient were far more complicated than the actual logistics of organising it. The participants described how they were balancing the need to keep the ambulance in the village as a resource in local emergencies with the need for a patient to be transported to the hospital. Many times, if the patient was stable and pain was manageable, a taxi service or a private car could be used to transport the patient to hospital to keep the ambulance on site in case of a local emergency.

What we need to think about here, that you don’t have to think about in a city is that we might only have one ambulance and if we send it away we will be without an ambulance for several hours. And then if one patient emergently needs to get to Lycksele, but isn’t unstable, like if one suspects a fracture and can be sent in a stretcher car, then we prefer that. Because if we are without an ambulance and if someone gets a heart attack or someone here in the village gets seriously ill … so that is one thing you need to think about in these situations in rural areas, that are unique for rural areas.

As to solving logistical challenges, the participants found ways to solve these problems in medical emergencies if necessary and did not perceive them as challenges that could not be overcome. The greatest contributors to transportation problems were weather conditions and reduced ambulance availability. If a helicopter was not available due to weather conditions and all the land ambulances in the area were occupied, the patient would be kept at the local emergency ward at the cottage hospital for stabilisation, waiting for a helicopter or ambulance to arrive. The weather in this area changes very quickly and, due to weather conditions, the helicopter cannot fly for half of the times required. If the helicopter could not fly the entire way due to bad weather, but a ground-based ambulance was available, the patient could be loaded into the ambulance and the ambulance would initiate transportation, only to rendezvous with the helicopter along the way. As such, the flexibility of the transportation system allowed physicians to find alternative solutions to the challenges. Often, participants described that they needed the skills of the anaesthesiologist working in the helicopter rather than the transport capability of the helicopter service itself, as the anaesthesiologists could induce anaesthesia on site. This could enable the rural physicians to reduce fractures that could not otherwise have been treated in alert patients. One participant described how an anaesthesiologist was transported to the cottage hospital by taxi when the helicopter could not fly. If the patient was stable, the next of kin could be asked to drive the patient to Lycksele hospital rather than have the patient wait for an ambulance. This was the preferred way to transport the patient if the pain was manageable, as the patient would have someone to take him or her home from the hospital following treatment.

We have a service car that belongs to the cottage hospital. One time, a patient at the senior care facility had to be attended by a physician. All the ambulances in the area were occupied, and the only ambulance available was in Vilhelmina [about 70 km away], and it didn´t feel right to have the Vilhelmina ambulance drive all the way up here just to transport a patient for just 400 meters, so I used the service car and drove to the patient instead.

Overall, the physicians described the flexibility and adaptability of the transport system to be a great resource in their work, with the possibility of changing strategies midway so if one transport option was not available another could be employed.

Discussion

In this qualitative study, physicians were generally thriving when working in a Swedish rural area. Interpersonal relationships and the formation of a strong network between colleagues were crucial factors in the job satisfaction of the physicians. Logistical challenges that physicians encounter were frequently solved, sometimes by applying improvisational solutions.

To the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first to explore physicians’ experiences working in emergency medicine in a rural area where the physicians also live permanently in this rural community. A previous study by Sturesson et al described that incentives for physicians working in rural areas temporarily were an acceleration of the process of being recognised as a specialist or simply increased salaries19. The obstacles were perceived as having fewer opportunities concerning personal and professional life for themselves but also for their family members. Overall, the participants in Sturesson’s study considered it unattractive to work permanently in rural and remote areas. Most of the participants stated that they did not want to move to a rural area unless it was absolutely necessary19. In the present study, it was hypothesised that this would be the case as well. However, throughout this study it became clear that the participants worked in an overall thriving environment where all physicians expressed enjoyment in their work. The majority of the participants also lived in rural communities themselves, suggesting that the study participants either wanted to both live and work in a rural environment, or that the physicians had other previous attachments to the area, either through family connections or other connections. This notion is confirmed by the literature that shows those physicians who are drawn to the rural work grew up in that environment or had a passion for the nature in those areas4,20.

The physicians expressed unselected intake of patients at the cottage hospitals and variety in their work as major reasons for their job satisfaction. They enjoyed hands-on tasks, where the participation in the manual work with the patients gave the physicians a vital role in medical emergencies. This finding differs from the literature, where rural GPs are just one of many providers in medical emergencies in some places. In these settings, ambulances have direct communication with the hospital and may bypass rural physicians and instead drive directly to a hospital21. In the rural areas of Southern Lappland, however, the ambulance often transports the patient to the cottage hospital first, having a local physician-on-call assessing the patient while the ambulance is waiting for potential continued transport to Lycksele hospital.

Other elements facilitating thriving were the systemic factors supporting rural emergency medical work by creating educational opportunities and having a system in place managing both transportation of patients to the hospital and, if necessary, transporting physicians to the patient. The educational opportunities for emergency medicine in rural areas in Sweden were found to be groundbreaking. This includes the rural residency program for future rural GPs, courses held by the Swedish Society for Rural Medicine, and connections to ongoing research at the Rural Medical Centre22. Studies have shown that physicians around the world face educational challenges to equip themselves for rural work in general23, and for emergency medical work in rural and remote areas especially4,24. The literature describes the importance for medical graduates to practise in rural settings in order to gain a broader understanding and knowledge of clinical practice25. This substantiates the findings in the present study. Our participants suggested that transportation in itself was not an issue in this setting. It was rather a discussion of whether to send the patient to hospital, keep the patient at the cottage hospital, or send the patient home, and what mode of transport to use, depending on the medical situation. This finding is supported by a Norwegian study that finds transportation of patients is functioning fairly well in the healthcare system in Scandinavia, even in rural areas26. That is in sharp contrast with studies from other parts of the world where transportation is described as a major issue in medical emergencies4.

A thriving element was the good relationship of physicians with their referral centre, Lycksele hospital, in this study. Mutual understanding of the geographic reality in which the rural cottage hospitals operate was believed to contribute to this relationship. Additionally, the more support the cottage hospitals can get from their specialist colleagues, the more patients may be treated at the local cottage hospital, which may reduce pressure at the emergency department in Lycksele. Previous literature confirms the importance of supportive professional relationship but also takes into consideration that these relationships might be unattainable for locum physicians and newcomers who have not yet established professional networks4,27. In a Canadian study, the authors recommend building and strengthening the relationship between rural and urban emergency departments to promote a shared understanding and in turn heighten quality in patient care28.

A final thriving factor found in this study was the physicians’ problem-solving attitude and adaptability to the rural challenges. This inclination to fix things in part evolves from the demands of many situations and lack of other resources, and it may enable the physician to take action in a situation regardless of prior qualifications. In addition, the personal characteristics of physicians choosing to work in rural emergency medicine may equip them to handle challenges and unforeseen situations. This notion is corroborated in the literature from around the world4,20,27.

Despite the findings of a thriving environment in this study, studies on rural health display challenges to recruit physicians permanently1-4,19-21. This was not described as a major issue for the participants in this study, but this may be due to the nature of the study, investigating medical emergencies and not the general structure of rural work. However, clinical observations at the two cottage hospitals indicate that this region indeed struggles to recruit physicians permanently, but are working around the problem by employing recurring locums familiar with the area.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was that two of the authors (NMSH and EF) had an active involvement in the clinical work in the area. They got to know the participants in the study as well as the community in which they lived and worked. This provided a deeper insight into experiences and challenges the rural physicians faced when working in emergency medicine in this setting. During the first author’s stay in Southern Lappland and following discussions with the author EF, challenges not mentioned in the interviews became evident along the way.

A limitation to the study was that questions were not explored in depth during the interviews as the author’s prior understanding of rural emergency medicine from the literature centred on more practical aspects of the job, which were later explored in the interviews. Another limitation of the study was lack of critical informants among the interviewees. Due to the timeframe of this project, it was not possible to interview locum physicians and physicians who for various reasons had moved away from the rural areas. This may have given the study a one-sided perspective of the documented experiences. One author completed data gathering, management and data analysis limiting the realm of broadness the study could have otherwise provided.

Conclusion

The participants in this study reportedly work in a generally thriving local environment in a rural healthcare system. A close-knit professional community across the area founded in the specialised rural residency program along with personal characteristics and problem-solving attitudes are factors contributing to the thriving elements. Further research is needed to fully explore the experiences or challenges the rural physicians face in specific medical emergencies unique to rural areas, as well as to explore how recruitment to this area can be made attractive. The findings in this study are relevant for future physicians interested in rural emergency medical work in Southern Lappland as material for mental preparation.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the study participants for their time and involvement.

References

You might also be interested in:

2014 - Knowledge and perceptions of Chagas disease in a rural Honduran community

2005 - Rural nursing unit managers: education and support for the role