Introduction

In Brazil, sex work is marginalized by society, but female sex workers see prostitution as just a job – a way to achieve financial independence, autonomy, and personal fulfillment1-3. There exists both prejudice and discrimination for the practice of sex work in society4. It is generally considered that sex must be restricted to marriage, and that sexual practice should strictly be for procreation and the satisfaction of male pleasure. Female sex workers (some of whom are married), on the other hand, consider sexual practice a tool for financial purposes, their bodies being an instrument for obtaining profit5-7.

Even though in Brazil (and other countries), prostitution is not a criminal practice, workers using their bodies for sexual practice are still ostracized by society when they reveal their vocation. Sex work is charged with stigmas constructed historically and socially, and is labeled with the most diverse prejudiced stereotypes, leading to compromised well-being, health, relationships, and consequently, quality of life for sex workers8,9.

Women living in rural areas of Brazil suffer from inequalities of gender, class, and race. Rural agricultural workers, especially women, face a constant struggle against the process of social exclusion10-12. 'The scenario in which these sex workers exist is based on the concentration of land, capital and income, and precarious labor relationships'11.

In a context of undervaluation, exploitation, and oppression of small farmers who survive in subsistence agriculture, some women suffer from even more profound inequities – consequences of the patriarchal culture of subjugation, objectification, and allocation to private spaces of homes for the duties of motherhood; in other words, taking care of the children11-14.

Some women (especially those who are separated, widowed, or abandoned by their partners) do not have resources for subsistence; they might have many children to maintain and support, and (without the support of society and the State) struggle to support their family with subsistence agriculture. Therefore, they find in sex work a way to obtain income for sustenance, autonomy, and independence in an environment of exclusion and invisibility, working seasonally between rural and urban areas11,12,15,16.

Several stigmas are associated with female sex workers: breaking with the cultural determinism of the social construction of being a woman; occupying the public space of the street to carry out their work; paid sexual practice as their object of work; and being considered by society as filthy, sinful and deviant. In addition, they also suffer from intersectional inequities of race, gender and social class, among other stigmas and stereotypes attached to them. These negative attitudes are primarily responsible for contributing to female sex workers' greater susceptibility to social vulnerability and prejudice, exacerbating invisibility before the State and society, and keeping them in a vulnerable position when it comes to facing violence from customers4,12,14,17.

As the aforementioned stigmas intertwine with the sociocultural living conditions of this group of sex workers, social inequities and inequalities become notably more potentiated and deepened, greatly interfering in the health–disease continuum, in quality of life and well-being, and affecting family survival and livelihoods. These women already experience difficulties because they live in a rural area: some are mothers and wives; some are microfarmers, who derive part of their income from working on the land and supplement it with income from sexual services – in periods of drought, they have to work hard to help support their families. Living far from the main urban center also contributes to their difficulties12,17. Furthermore, female sex workers suffer from stereotypes and stigmas as a result of the consensual sexual practice adopted as a service to be offered in their profession, with the body as the object of work. Stereotypes and stigmas about sex work also affect a woman's readiness to reveal their profession to healthcare workers, resulting in reduced access to appropriate health services3,10,18.

Women involved in sex work (the technical term given by the Ministry of Labor and Employment, is ‘sexual professional’) offer a service for renting their bodies, which enables autonomy and financial independence and well-being, meeting personal and family needs6,19. The concept of quality of life is appropriate for this type of study because it is broad and at the same time subjective, going beyond the reductionist concepts of health and biology, and expanding to social, affective, emotional and psychological issues, and all of the factors that contribute to guarentee human rights. The wide range of indicators that structure this term influences the conjuncture of variables such as education, culture, leisure, life expectancy, biopsychosocial complex, and above all, the context of individual insertion in this interrelated system20.

In this context, Phenomenological Theory is important for studies with vulnerable populations such as female sex workers living in rural areas, whose lived experiences are borne of singular and multifaceted contexts and the meanings of vulnerability and quality of life, are perceived from the understanding of how these subjective themes and intimates are experienced by female sex workers in everyday life. For this study, we looked at the experiences of female sex workers. These women exercise freedom and autonomy over their bodies, escaping social determinism (breaking with social constructions of gender, sexuality and behaviors expected of women in societies ruled by patriarchy). Thus, because Sartre considers that there is a freedom that is intrinsic to any human being, for the author, freedom and man are understood as one thing because in the world any human being will do, act and choose, in an attempt to be definitive21,22.

Studies focused on Sartre’s phenomenological approach lead to the understanding of the other while being a self-to-self, whose conduct of the self-seeking it seeks to be (in other words, female sex workers are the self-for-self: when they think of themselves and try to be a being in search of freedom, they try to break with patterns and determinisms socially constructed for being a woman), which results in an affective and effective view on the experiences acquired by the human beings in their day-to-day experiences22,23. In this case, female sex workers who seek to understand and support each other, in a stigmatized and marginalized environment, are better able to survive in the world and satisfy their need for well-being and quality of life.

Therefore, when opting for a phenomenological analysis of, and reflection on, the meanings attributed by sex workers to quality of life, it will not be possible to have interpretations focused on the moral values that tend to judge the professional practice developed by this group of women22. In addition, comments or shallow analyses (based on common prejudiced thinking) that tend to perpetuate stigmas and marginalize sex workers should not be considered4. Nor should there be a discourse that tries to diminish these women and keep them invisible as citizens, just because they practice a sexual freedom that provides income and means to have quality of life, an escape from what is constructed and expected socioculturally for women – that is, the behavior expected of women in patriarchal societies4,23.

Furthermore, the reflections to be built on the meanings of quality of life in the experience of sex work by women are justified by providing opportunities for health professionals to look at a socially stigmatized population group4 placed in a situation of vulnerability by the State, in a poor, semi-arid region of northeastern Brazil. We emphasize that quality of life is not restricted to sexual and reproductive health, and does not refer only to STI prevention, but it is a right that should be encouraged and understood as basic to life and human dignities, and refers to the rights of a person, with total respect for the body and work5,6,9.

Therefore, the objective of our study was to understand the meanings that women in the experience of paid sexual work living in rural areas attribute to the quality of life, from Sartre’s phenomenological perspective.

Methods

Study design

This is a qualitative study, based on Sartre's philosophical–phenomenological approach. We should note that phenomenology does not stop at establishing causal relationships or finding/explaining phenomena and subjectivity; rather, it values directly describing the experience as it is21. Research anchored in phenomenological approaches, such as Sartre’s, directs the researcher to stick to the feasible data of the phenomena, based on the understanding that existence must precede the essence, since human beings have intimate wills and desires that lead them to seek their freedom, even though many experiences and learning throughout life are not pleasant or successful. Freedom starts to make sense to the human being, insofar as they perceive its essence, since throughout life they resignify desires, feelings, practices and behaviors22,23.

The phenomenological approach based on Sartre’s philosophy presents the human being. In this study, it is the woman in the exercise of paid sex work and living in a rural area, in their ontological situation; that is, women who experience autonomy and sexual freedom in their bodies, as well as having sexual practice as a way to obtain income and seek quality of life. For Sartre’s phenomenology, we must consider what is lived through the details of each situation, such as the context, the surroundings, the place, the past, and all the relationships established within his world, that is, the world of the human being, during the course of his or her life22,23.

Search location, selection, and recruitment of participants

The study participants were sex workers from the Sertão Produtivo Baiano region, an area characterized by rural subsistence production, agricultural economy, and a population residing in rural communities with 19 municipalities in its region of coverage, and little more than 400,000 inhabitants23. The sample was non-probabilistic for convenience, having 30 women who met the following inclusion criteria: being 18 years old or older; performing acts of prostitution during the collection period; and living in the rural area of the region. We used a snowball technique, a device for access to participants, because this is a group of social invisibility, with few quantitative records at regional or national level, making population estimates difficult24. The Community Health Agents (CHA) who accompany rural residents were responsible for inviting the participants in advance and highlighted the voluntary and anonymous nature of participation. It should be noted that the CHAs were not involved with the study, but helped with contacting the women.

Participants were approached via professionals from the Regional Testing and Counseling Center of the municipality where the Alto Sertão Produtivo was based, in an area of prostitution close to the open market in which rural workers and small farmers sell their cultivated products, and where sex workers take advantage of market days to perform sexual services. Before proceeding with the collection of information, researchers met weekly (starting November 2016 and ending April 2017) to plan. This is an important step for qualitative research based on theoretical references (such as the present study with phenomenology references) and requires researchers to deepen the theme, in addition to observation and familiarity with the participants and their daily lives. Those responsible for the project made use of weekly meetings to carry out an extension project linked to a university in the region (always at the end of the day, before the female sex workers returned to their rural homes), with the purpose of facilitating feminist workshops for the sex workers who subsequently contributed to the study. The feminist workshops preceded data collection and served to bring the participants closer, to create a bond with them and better understand their circumstances and daily life.

The workshops were important for dialogue and exchange of knowledge about health education and life in sex work, and to get to know women more and better understand their context (sex worker and rural woman with seasonal displacements between urban and rural areas) and their views on what constitutes well-being and quality of life. These weekly outreach activities took place in a meeting room provided by a church in the prostitution region and close to the fair, known as 'Beira da Lagoa', a place that also has bars and rooms used by women arriving from the countryside to perform their paid sexual services with customers, and also by farmers and/or other sellers of fresh food and groceries (mostly marketers from other municipalities or the countryside).

Data collection

Data collection took place between April 2017 and June 2018, with those women who accepted the invitations, in the meeting hall of the aforementioned church, located close to the region and the working environments of these women. The collection process lasted for another year due to the difficulty in recruiting participants, and finished when the ideal number of participants was reached so that it was possible to reach saturation.

Data were collecting by applying a script prepared by the researchers. The script included items for the characterization of the participants using two open questions to guide the interview in-depth: (1) 'Tell me what you mean by quality of life, as a sex worker'; and (2) 'Tell me how you experience well-being and quality of life when you are a sex worker and a rural resident'. The questions structured for characterization included the variables age, education, religion, job satisfaction, and use of condoms and contraceptives. We recorded the interviews (average duration 35 minutes) using a cell phone. With the phenomenological interview, we could deepen (without the interference of the researcher) the subjectivity around the theme and the connections established between needs, well-being, achievement of quality of life, the exercise of sex work, and being a resident of the countryside, while retaining the important and subjective marker of the human being within the health–disease continuum.

Data analysis

We organized and transcribed the interviews in full using Microsoft Word 2016 software, then subjected the transcriptions to interpretive analysis (Sarte’s progressive–regressive analysis). This type of analysis contributes to the researcher’s understanding of unique but universal aspects in the lived experience of people based on a back-and-forth movement of the elaborate narrative of their existence, and favoring the analysis of the ontological freedom of being and their understanding of the condition of freedom21-23.

The interpretations favored the theoretical reference of Sartre because it allows analysis from the relationship of the human being with the phenomena to be investigated (the meanings that sex workers attribute to quality of life), making it possible to understand the ontological duality that comprises this being: without-in-itself (the conscience) and being-for-itself (something that is not consciousness, but the reality external to it). This phenomenological philosophy points to consciousness as a classification of the being turned away from itself, in the search for its being. The being-in-itself (the being/person itself) is full and stable, and his or her 'ontological duality is marked by a relationship that, on the part of the for-itself (the nothingness), tries to achieve a synthesis of becoming an in-itself being: himself and for himself (the being that seeks freedom)' 25: 295.

Nothingness does not have its genesis in being, but in an anthological pole that reveals human reality. It is through human behavior that nothingness is revealed. With this dubiousness, there is the presentation of the person as an insufficient being, and for this reason, he or she understands freedom – freedom that makes it possible to seek sufficiency, the filling of voids and desires, because his or her existence lacks substance and sense22,25.

The analysis proposal made it possible to interpret the meanings (and particularly the meanings built on quality of life) based on the experience of women during the daily life of sex work, combined with being a resident of the rural area. Sartre’s phenomenological interpretative analysis was preceded by, and facilitated with, the dialectical hermeneutics of the narratives and their stages of operationalization of the data to situate the researcher in the context of social actresses26.

For this study, the second level of interpretation (hermeneutic–dialectic) was considered to assist in the analysis because the interpretation was based on individual communications, on the observation of customs, behaviors, meanings, and rites. This analytical method occurred in three stages: (1) ordering the data; (2) classification of data, from the convergences and divergences of the interrogations of the structures of the narratives considered relevant for rural sex workers, and afterward, with the survey of the categories; and (3) final analysis favored with interpretations26 and articulations with the theoretical reference – in this study, Sartre's ontological phenomenology22,23.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Higher Education Center of Guanambi with protocol number 2,007,080 in 2017, respecting all the principles that involve research with human beings, including the reading and application of the informed consent form. Before data collection, informed consent forms were provided to all participants. To guarantee the anonymity and confidentiality of each sex worker, a code was assigned, the letter 'P' for the participant, followed by a number, such as P.01, P.02 (...) until P.30.

Results

Among the 30 participants in this study, most women were between 18 and 35 years old (78.26%), had a low level of education (53.62%), identified as black (59.42%), identified as Catholic (55.07%), had worked for less than 5 years (68.12%), were not satisfied with the profession (55.97%), used condoms during sexual intercourse (63.77%), and reported using hormonal oral contraceptives (66.66%).

The profiles obtained from the observations and interaction with sex workers living in cities that make up the Alto Sertão Produtivo Baiano showed that they were residents of the rural area and/or cities smaller than the region's headquarters. Many of them were married or divorced, and were in paid sexual service to supplement their income in order to support themselves and their families. Some of the women had been abandoned by their companions and were unable (due to lack of financial resources) to maintain subsistence agriculture; they were frequent visitors to the centers of the street markets to advertise sexual service and had clients who were mostly traders and marketers. They rented rooms from owners of houses and bars, which indirectly facilitated paid and consented sexual service.

The narratives we collected conveyed some meanings that referred to the women’s daily lives, both as related by sex workers and observed by researchers. In this way, it was possible for researchers to better understand the similarities and meanings, allowing us to make inferences in the subjective dimensions organized and operationalized by hermeneutics–dialectics. From these inferences, three categories of analysis were evident: the understanding that sex workers from rural areas have about quality of life; whether they believe they achieve it or not (the quality of life); and what is important to achieve well-being.

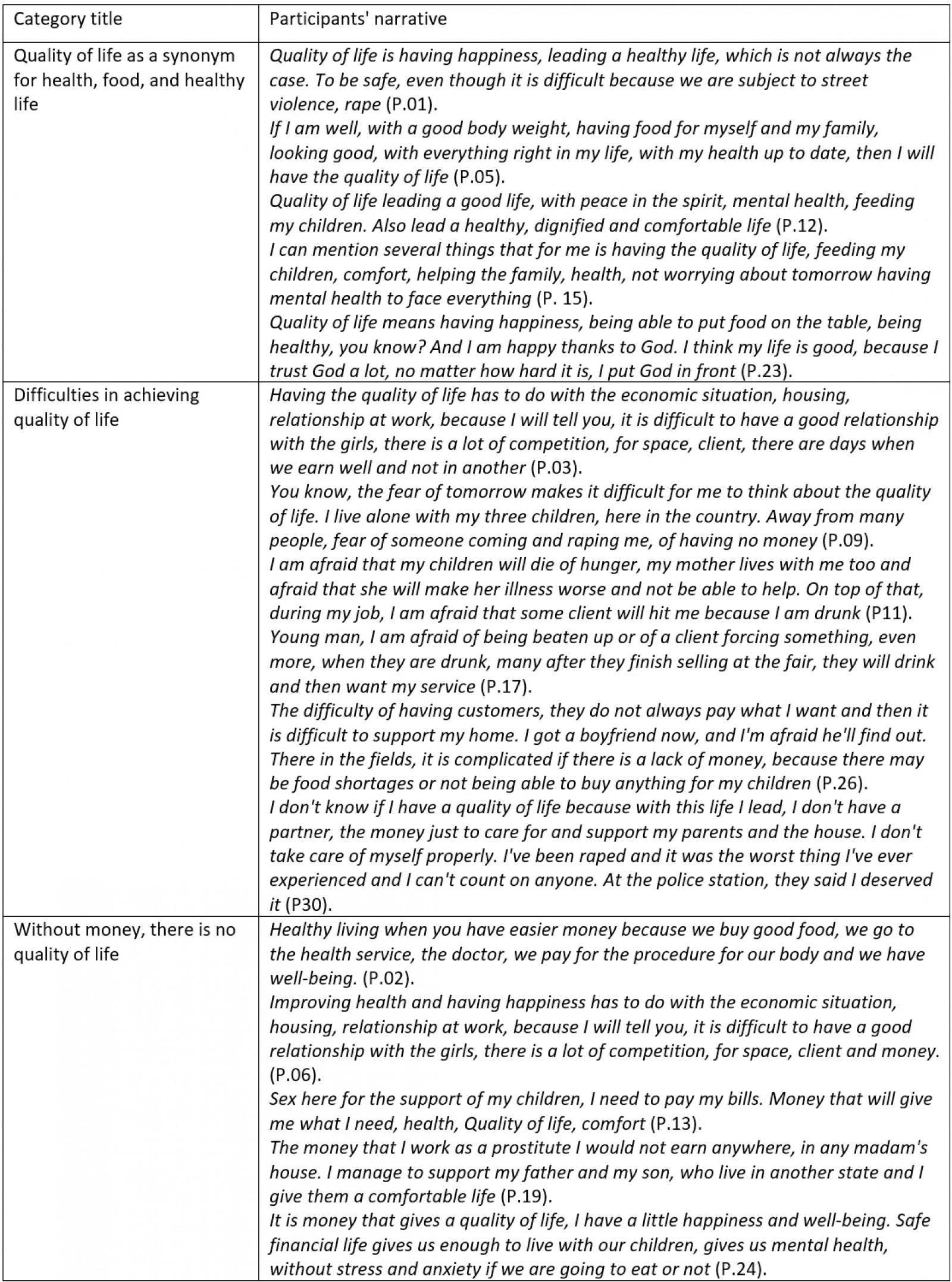

Thus, three categories of analysis emerged, organized in a framework: (1) quality of life as a synonym for health, food, and healthy life; (2) difficulties in achieving quality of life; and (3) without money, there is no quality of life. Next, we structured a table organized by category and the synthesis of narratives of participants who converged for each category (Table 1).

Table 1: Organization of categories with the narratives of female sex workers in the rural area of Sertão Produtivo Baiano, Brazil (n=30)

The sex workers' narratives above reveal meanings that refer to their daily lives in the context of their struggle to survive in a region far from the big city centers. Their existence is hampered by living in the countryside and having to move to the city to obtain income to guarantee their own survival as well as that of their children and, in some cases, their relatives.

The women’s fears of not being able to achieve the goals of income, food, and health, or of suffering violence or even death, are significant obstacles in the pursuit of quality of life. The fact that these women are sex workers reveals the freedom they intend to obtain in this profession, since their existence is marked by facing situations of vulnerability and social problems for survival and quality of life. Moreover, sex workers struggle, as multifaceted women, for freedom and recognition by various levels of society, because they are constantly fighting against patriarchal social constructions that dictate how a female should behave.

Discussion

The meanings that sex workers give to quality of life reflect the day-to-day issues peculiar to the life of a prostitute, as well as their precarious circumstances in the rural area where they live. It is also considered that learning and experiences are acquired in contact with clients in the sexual service while being a woman and mother who earns income from sex work1,14,15. Therefore, the ideas above are based on three transversal categories: (1) the understanding that sex workers have about quality of life; (2) the difficulties encountered both in the profession and in the countryside; and (3) the importance of money as a means to have well-being and quality of life.

The narratives point out that the perception and the reach of quality of life, based on phenomenology, are not limited to the presence of health or absence of disease, but include other subjective aspects, such as healthy life, food, comfort, feelings, and emotions (positive and negative), and above all, financial safety. Consequently, they unveil the broader sense of quality of life as something geared to the subjective sphere of what is important for well-being and happiness.

Therefore, as in other previous surveys carried out with female sex workers, the notion of quality of life for women who perform sexual services and come from rural areas is intrinsic to emotions, to the meeting of needs, and to subjective, behavioral, and attitudinal actions that provide balance in the health–disease continuum, as well as coping with adversities from being a sex worker and, above all, acquiring income to obtain food and subsistence and comfort items3,16,27,28.

Such subjective aspects show the meanings built into the ontological conception of the without-in-itself (consciousness) and being-for-itself (something that is not consciousness, but the reality external to it), by revealing the being through language, gestures, feelings and the relationships established with their context for freedom1,7,22,23.

Understanding of the psychological and emotional aspects, including fear of violence or lack of money and food, is connected to the meanings that sex workers attribute to their own existence, and to the dangers of being a woman in a sexist country, ruled by a patriarchy that has high rates of femicide and gender-based violence. Added to the above issues, there exists prejudice against sex workers, perpetrated by clients, society and the State, denying them their citizenship rights, rendering them marginalized and socially invisible7,22.

These marks that these women carry (because they live in the countryside and are sex workers) refer to the experiences acquired throughout their existence, defined by the Sartrean method as temporality. This term gives the idea that time (past, present and future) allows a constant movement of transformation and adaptation of the human being to different realities. This favors the constitution and obtaining of meanings that people give to some situations that cause marks or transformations, or that have impacted them throughout their existence22.

The peculiarities of being women, sex workers, residents of a rural area and often black and poor make this group of women vulnerable and insecure in their duties as prostitutes, with the potential for rape or other violence a constant fear. They are judged as criminal by society when they expose themselves on the street to earn money in exchange for sex, losing the protection they should have from the State. Thus, when rape or other violent acts are perpetrated against these women, the aggressors go unpunished, and the crimes committed against them fall into oblivion16,17,28,29. This condition is reflected in the high rate of femicide in Brazil, where being a woman is enough to justify the behavior of a 'man', and his 'good customs' of a dominating male, whose sexuality can be expressed in public spaces, being encouraged since adolescence. This social construction of being a man in a society ruled by patriarchy points to the 'ideal construction' (pejorative) of the female figure, especially if it is linked to some panorama of expression of female sexuality, in which the woman may only express her sexuality in the confines of her private home, and only with her husband5,13,16.

A study developed in a southwest Asian country showed that the financial independence and autonomy achieved by prostitution allows, in addition to satisfying personal needs, the workers to protect themselves, their children and other family members, and provides a means to create support networks to deal with the consequences of violence. In that same study, the workers were also protected by the intervention of the State, with public policies and recognition of the sex work profession guaranteeing legal support, access to labor rights, security, and protection from violence, all of which contribute to a good quality of life9. In this sense, the understanding of quality of life (even if incipient and not anchored in theoretical aspects) is linked to what is pointed out in the sphere of human and constitutional rights. For the sex workers studied in the present work, quality of life includes the freedom to express their opinions, beliefs, ideas, senses, emotions and values. In addition, when discussing the concept of quality of life, sex workers emphasize that the meanings of quality of life are expressed in the daily experience of being a woman performing sex work and living in a rural area28,30.

Some sex workers associate well-being with greater access to health services, some emphasize the psychosocial and emotional aspects more and some consider purchasing power for goods and services (as well as access to different sectors of society) as the primary factor in achieving well-being30. Understanding this is essential because these women suffer from intersectional concerns involving issues of race, class, and gender, and many are also rural workers (it is noteworthy that they do not have financial assistance from the government and, therefore, have difficulties maintaining family farms). Most rural sex workers make up the base of the social pyramid, where quality of life is associated with the need for subsistence. Accordingly, they are always in search of better socioeconomic conditions for themselves and their families, and, consequently, their success or otherwise significantly contributes to their well-being2,4,5.

This fact occurs, a priori, due to the fact that there is an oscillation in the gender roles attributed to women, as well as in the social perception of what it is to be a sex worker – a woman who sometimes experiences pleasure and values herself, sometimes focuses on her work and remuneration to meet the basic demands for subsistence. Pleasure itself, self-worth and subsistence are essential for the survival of sex workers in society. This will for survival reveals that sex workers are in a state of struggle to exist in patriarchal societies. This occurs because the very concept of a woman as a sex worker contradicts the socio-natural determinism of the Christian woman subjugated by her husband, with sex professionals having the ability to obtain income from sex outside the marriage7,13,14,31.

The sense in which money and financial security are understood (important factors in quality of life) is presented with an ambiguous meaning, real and subjective, as evidenced in a study carried out with French sex workers, showing the importance of financial stability when associated with sexual service with customers2. The meaning is real, because it enables subsistence and access to goods and services, and subjective, because it is associated with pleasure, which is experienced in a dubious way in its context – with customers (in which there is a transaction of income for the pleasure of a man) and with their steady companions/partners to obtain self-esteem, affection, feelings and balance of emotions2,21,23,32.

In Sartre's perspective, time, and (in this case) the past, does not determine people's actions in the future. However, the past reflects on present decisions and therefore cannot be modified, but it can be re-signified through attitudes, behaviors, actions, and other ways of coping22. In this sense, the participants' narratives express, within Sartre’s regressive aspect, that considerations about the quality of life for female sex workers are permeated both by learning and by the needs and experiences lived in the scope of sexual service1,8,12,13.

For these reasons, quality of life is understood by sex workers to be broader than issues involving the health–disease continuum. For this group of women, quality of life encompasses other factors, such as socioeconomic factors, psychosocial well-being, positive self-image and better health conditions, as well as guarantees of security and protection from the government to develop its service and reduction of aforementioned social stigmas20,27.

In an ethnographic study carried out on the Amazon border between Brazil, Colombia and Peru, different aspects of the meanings of sexual satisfaction (money for subsistence and pleasure with steady partners) presented by sex workers residing in the Alto Sertão were revealed. Women develop a new system of social and decolonial production as they break with counter-colonial paradigms and desires (they are simultaneously mothers, sisters, neighbors, lovers, wives or girlfriends and 'whores') to obtain income and independence14. It should be noted that decolonial production is linked to a thought that detaches itself from the logic of a single possible world (capitalist), and points to a plurality of contexts and worldviews. It is a search of the human being for the right to be different and to present his or her thinking and positioning11,13,14.

Therefore, although there are people who associate quality of life with greater access to health services, there are some sex workers who associate it with psychosocial–emotional well-being, and others with the acquisition of purchasing power for the acquisition of goods and access to various sectors of society, such as health services3,30. Results of previous studies carried out with female sex workers from France, Africa, and in the Alto Sertão Produtivo Baiano (Brazil), revealed the importance of the money from sex work for such women mainly due to its role in facilitating the acquisition of goods2,3,32.

The factors limiting our study relate to the restrictions of the study universe that allowed us to present the meanings about quality of life for a segmented population group associated with a single context, among the several existing in Brazil and the world. Another limiting factor is the theoretical gap on the object of study when it crosses a taboo topic, and the lack of interest among researchers in further studies of sexual service performed by women in the rural area, in interface with the understanding they have about quality of life, as well as with the aspects of life and health of this group of women. Therefore, further research on the subject is needed in other regions of the world to broaden the discussions.

From these results, there is a need, in the practice of health professionals, for dispensation of humanized and empathic care, free of judgments, prejudices, stigmas, and discrimination. Many female sex workers yearn to vent, to obtain knowledge about preventive and health promotion practices, such as care and self-care and the search for quality of life. Thus, assistance for these women must be centered on universal, integral, and equitable actions, based on the promotion of human dignity and on the real needs as articulated by them.

Conclusion

Female sex workers associate quality of life with health, healthy life, food, and the means to obtain them. Being a sex worker in a poor, rural region of Brazil makes it difficult to achieve quality of life for several reasons, including the fear of problems arising from such work, which exposes women to violence, and worrying about whether they will have income the next day because money is essential to meet their needs and those of their families, as well as for comfort and well-being. Although people who break biological determinism exhibit behaviors and practices that are not expected of women, sex workers face adversity (women, who are mostly poor, black, and vulnerable) by choosing a vocation that allows for certain freedoms, including autonomy, financial independence, and survival in the face of social inequities, which are striking in the poorer regions of Brazil.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

You might also be interested in:

2014 - 'Heart attack' symptoms and decision-making: the case of older rural women