Introduction

Rural generalists (RGs) play a major part in prevention, early intervention, and care coordination across an extended scope of medical care in small rural communities where access may otherwise be limited by physical distances, transport and costs1,2. RGs are relied upon to deliver not only comprehensive primary care but also 24-hour urgent care and other specialist services in rural towns where there are often few local specialists3,4. The RG workforce has been in constant decline in an era dominated by new graduates determined to become specialists5. Meanwhile, the reliance on overseas-trained doctors in regional and rural areas continues to increase6. However, many rural communities remain strongly engaged with the RG model as the most cost-effective and sustainable way to deliver the required scope of medical services they need, and have been pleased with the emergence of more state-wide RG training programs to assist with a 'grow your own' approach7.

The Victorian Rural Generalist Program (VRGP) is based in Victoria’s five rural regions8,9. It aims for junior doctors to gain primary care experience with mentors working at RG scope, before enrolling in GP training and developing emergency skills and other advanced skills4. Around 35 interns are registered with the VRGP each year. The first postgraduate step of the VRGP is well established as a Rural Community Internship Training program, where RG1s (interns) train in small towns, doing 10–20 weeks of general practice experience with RG supervisors, case managed10. The second step of the postgraduate VRGP training, RG2 is undergoing expansion currently and intends to continue to provide supervised learning at generalist scope in smaller communities where RGs will eventually work; however, this requires an understanding of how to mobilise the supervision capacity for the RG2 group.

The current research about supervision enablers and barriers in rural general practice is quite limited. It is different from the role of metropolitan supervision because RGs are training learners across hospital and community interactions with rural patients within a rural context4,11. Supervisors in this setting need to impart medical ethics and professional norms that align with effective RG practice. Beyond this challenge, the broader literature denotes that supervision is becoming increasingly complex, as there has been a shift away from didactic learning to an informal and dialogue style, encompassing discursive and broader considerations of the learner, their work–life balance, and their learning needs12. For these reasons, the supervision workload can be high for RGs in small rural communities who have significant clinical demands13 and may find it challenging to find time for structured teaching and reflective learning14. Supervision capacity in rural practices is further challenged where domestically trained GPs, the group statistically most likely to contribute to rural supervision15, may be under-represented. Rural GPs have described the potential value of rural settings for vocational learning16. Australian junior doctors in rural areas are just as satisfied as their metropolitan counterparts, but significantly less so with the network of doctors supporting them and opportunities for their families17. While RGs must stretch their skills to meet the needs of communities3, junior doctors may find this overwhelming, without adequate support or back-up18. Promoting high quality of supervision at the RG2 step is a significant issue for up-skilling and retaining RGs to work in rural Australia19.

Supervised learning opportunities for RGs in the Victorian context may be somewhat different from places like Queensland, where RG doctors only need up to two rotations to receive all their training under employment with Queensland Health20. In Victoria, supervised RG training needs to be negotiated across 80 independent hospitals (most employing under one-year contracts) along with independent general practices.

With this background in mind, General Practice Supervisors Australia (GPSA) collaborated with VRGP to explore the enablers and barriers to supervising RG2 learners across a core generalist curriculum, in Victoria’s distributed towns.

Methods

This project was done between June and August 2021, as a collaboration between GPSA, VRGP and Monash University. The project was of interest to GPSA as the nation’s peak body advocating and supporting quality GP supervision, including that of RGs, in alignment with the Australian Government’s directions of an emerging National Medical Workforce Strategy21.

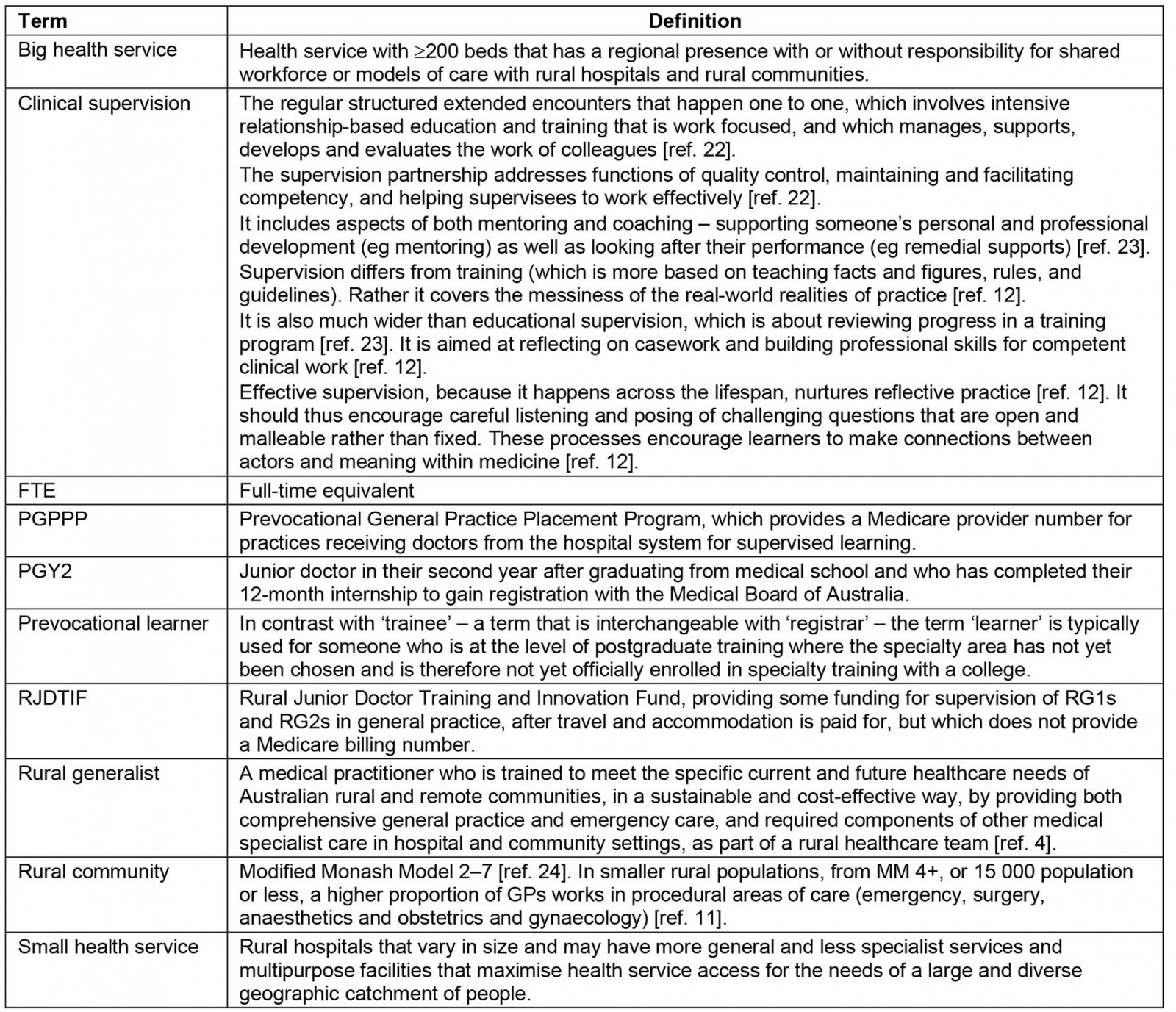

Definition of terms

First, a project advisory group agreed on the project terminology (Appendix I22-24) to support standardised interpretation.

Supervision requirements for rural generalists at postgraduate year 2

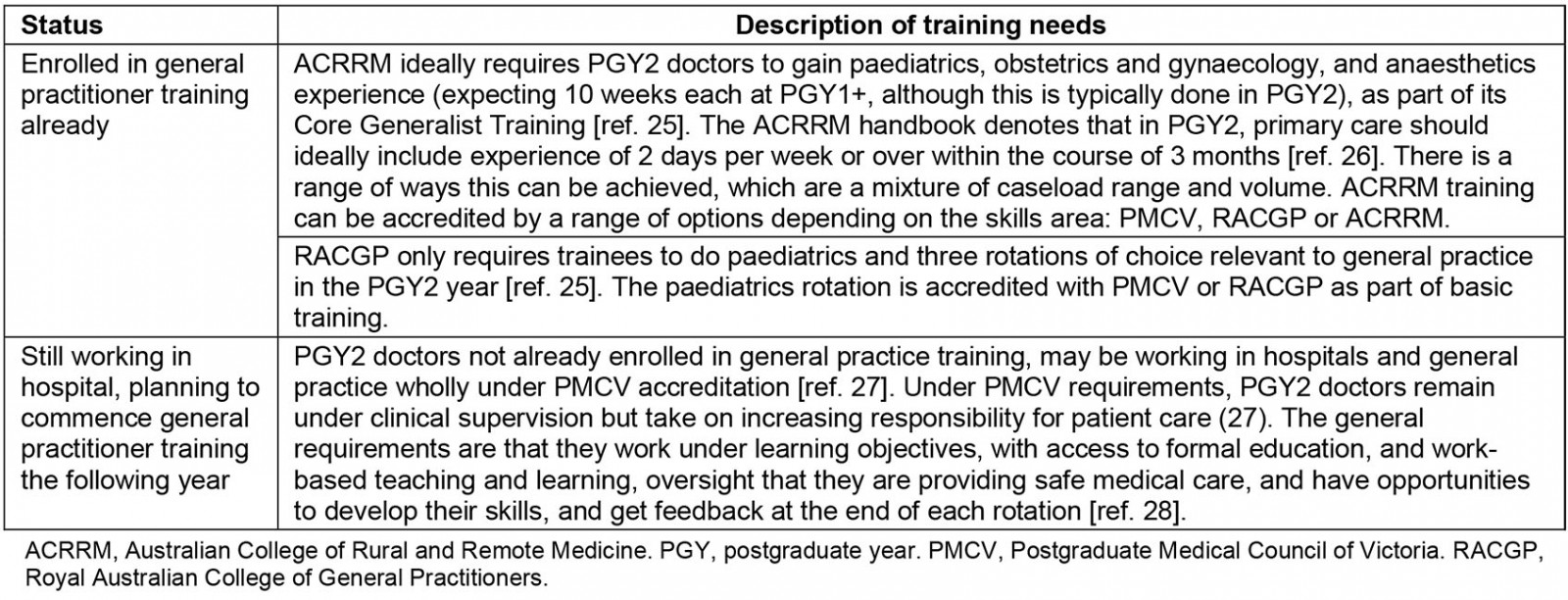

To aid understanding of the supervision scope and requirements of the RG2 group, the requirements for this level of generalist training were defined (Appendix II25-28). Whether pursuing prevocational learning base in hospitals or already enrolled in vocational training at this stage, clinical supervision should be matched to the needs of individual doctors.

Procedure and semistructured interviews

GPSA aimed to interview a range of practices and health services, whether supervising PGY2/RG2 doctors or not, to inform the topic. Maximum variation sampling was used to ensure the variety of participants would broaden the potential application of results in a context where all practice settings and communities differ widely29.

In collaboration with the project advisory group, a list of contacts was developed and checked for accuracy, including GPs, practice managers and small health service executives within each of the regions where RG2 training was being targeted for expansion. These GPs were in MMM 4–7 towns, working at generalist scope, and the health services were those engaged with the RG workforce. GPs/practice managers and health services were invited by email and phone (SMS). Participants read the explanatory statement online and submitted written consent whereby they selected an interview time with one of three trained qualitative interviewers, two of whom had a non-GP clinical background and academic expertise on supervision (BOS and PM) and one who had a business and systems-focused background (CT). None had prior relationships with the participants but two had a background in research about supervision models. Three email reminders were sent by GPSA, and regional coordinators also prompted participants to enrol in the study.

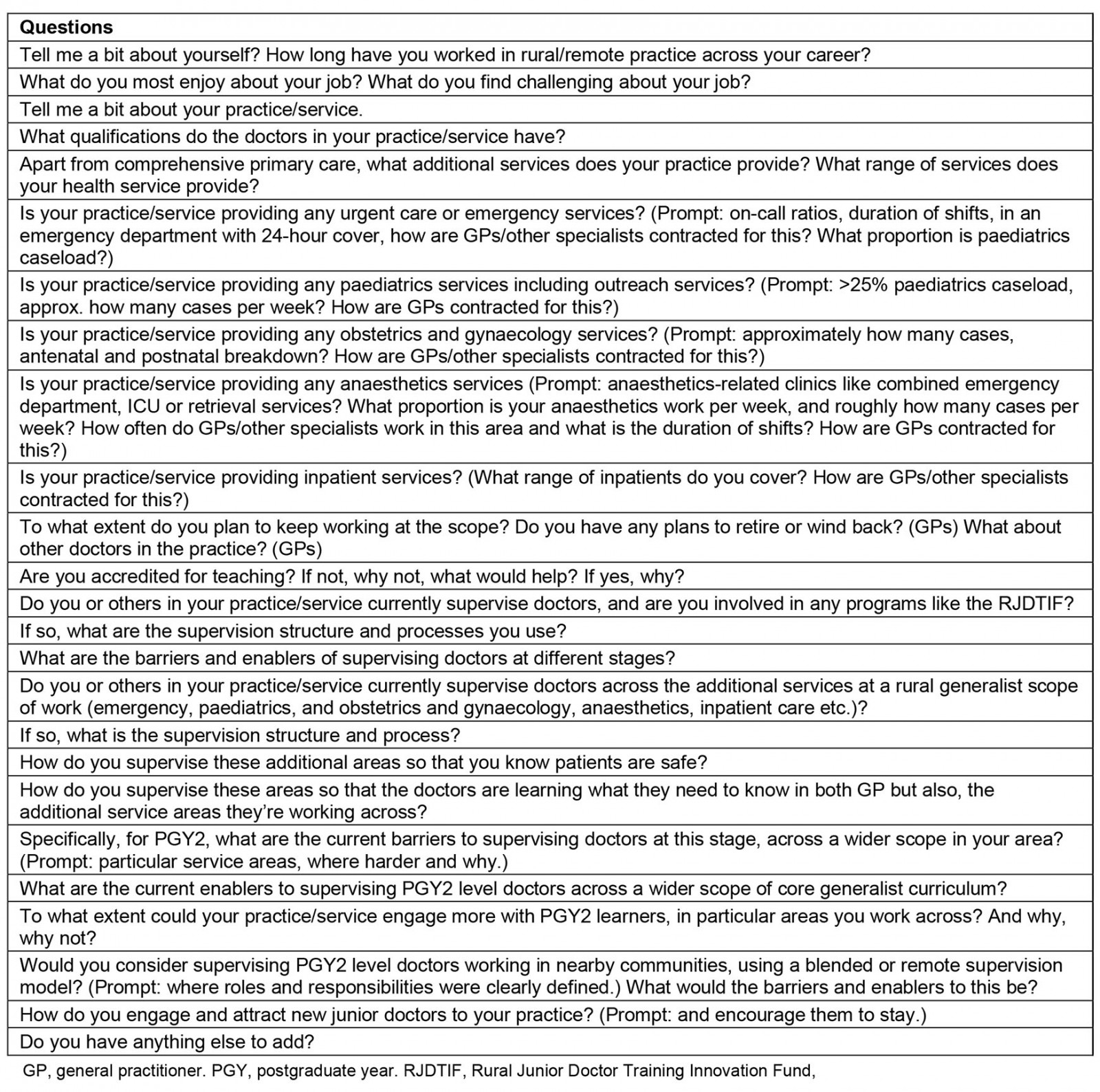

Interviews followed a semistructured interview schedule, tailored to interviewee (Appendix III). The schedule was determined in line with the literature review and supervision requirements of PGY2 and piloted with the project advisory group. The interview guide was circulated to participants prior to the interview to support deeper reflection. All interviews were conducted by Zoom or telephone, audio recorded and then transcribed verbatim. The duration of interviews was determined by participants. There was no payment for participating.

Data analysis

Each interviewee was assigned a unique identifier. The research team sought to interpret emergent findings using inductive thematic analysis. First, the research team read the full transcripts, re-reviewed recordings, and independently coded the data for meaning30. This happened with no pre-set coding frame, in line with inductive analyses processes. Additions and alterations to the codes were made as blocks of five transcripts were completed. The authors then double-coded another transcript, identifying reasonable concurrence with the codes and adding extra codes if these were relevant. The material was discussed, annotated and then organised into emerging themes, layering and reorganising these to make sense of the data31. All stages of analyses occurred with the research team working in distributed sites and meeting weekly online, to challenge each other’s ideas, reduce subjective biases and test any assumptions32.

After feedback from the advisory group, the research team pursued further rounds of inductive analyses by re-reading the original transcripts for meaning, and discussed the results regularly to allow for internal confirmation or disconfirmation32. This process enabled thick description and triangulation of a final set of themes and subthemes that the team agreed upon32. There was no pre-set coding framework, although the research team involved in coding were conscious of the existing literature as a backdrop for informing the analysis.

To aid analyses, participant characteristics were appended to unique identifiers and accompanied all transcript codes and thematic text showing stakeholder type as GP (general practitioner), HS (small health service) or BHS (big health service), and region of training as Hume, LM (Loddon Mallee) or BSW (Barwon South West).

Ethics approval

This research had ethics approval of Monash University (project no: 29263).

Results

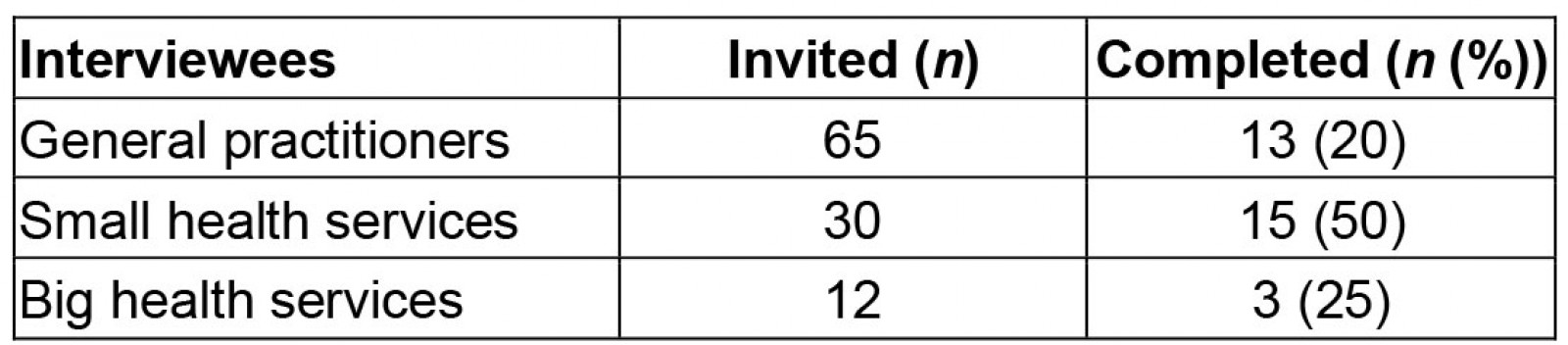

Of a sampling frame of 107 individuals, 29% responded, including 20% of GPs, 50% of small health services and 25% of big health services (Table 1).

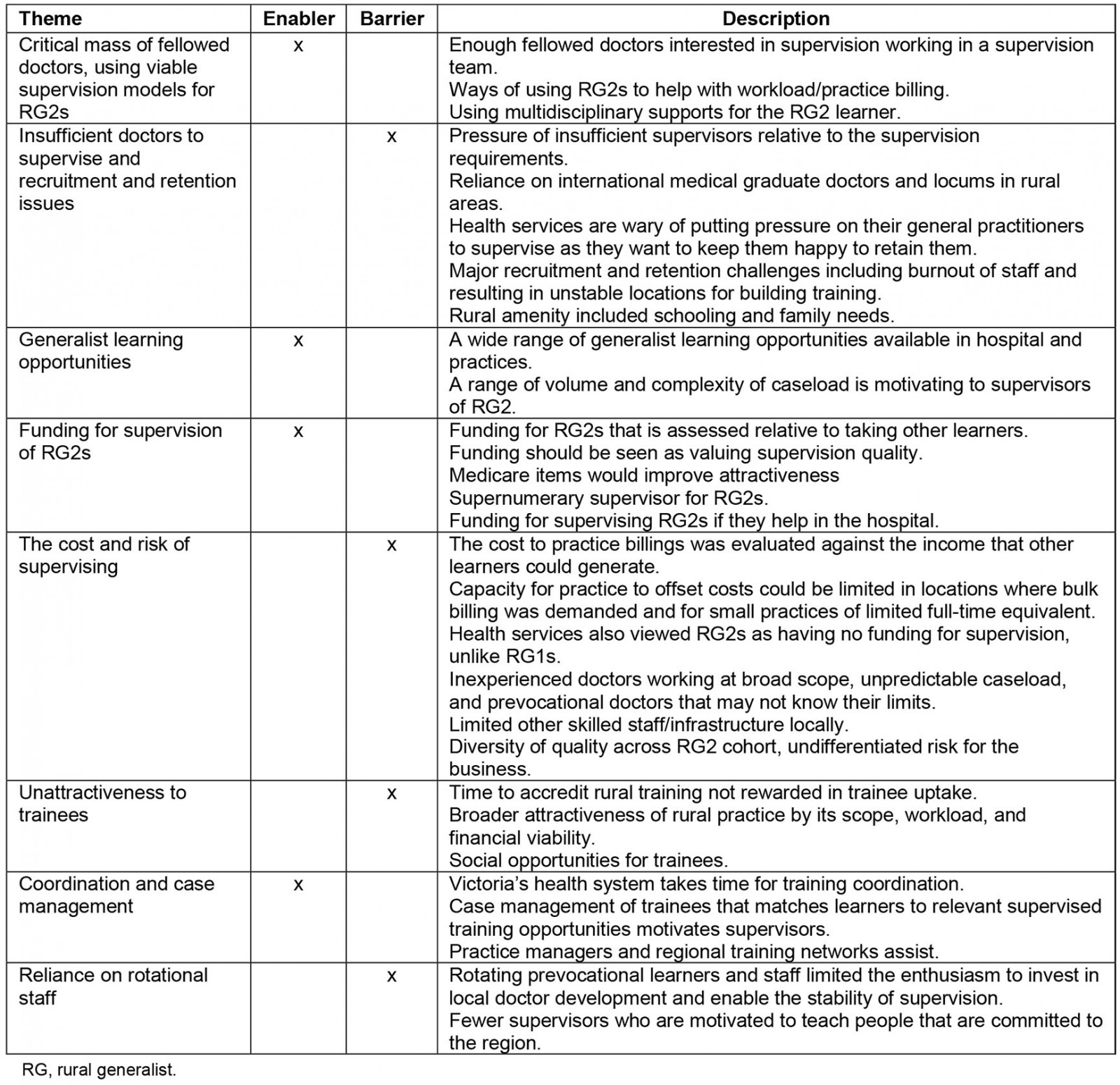

The themes are described in Table 2. Some enablers and barriers covered similar issues such as issues related to critical mass or funding/cost, whereas other themes stood alone as enablers or barriers. Where there was an overlap, the data on the enabler and barrier were presented consecutively, to provide juxtaposed perspectives of the same topic.

Table 1: Interview sampling frame and respondents

Table 2: Description of major themes

Enabler – critical mass of fellowed doctors using viable supervision models for RG2s

Having enough fellowed doctors interested in supervision on the ground was a critical enabler. This improved the viability of supervision: ‘… enough resources within the practice … I think makes it viable’ (123_GP(LM)). Spreading the supervision workload mitigated burnout: ‘it’s someone else’s turn the next day’ (191_GP(Hume)). Having more supervisors on deck was enabling because RGs ‘[wore] multiple hats … [and are] in demand’ (129_GP(BSW)), covering a broad scope of RG workload in small rural towns.

Some practices used RG2 learners efficiently around the practice workload:

… they just come with us to the nursing home … they can be seeing one patient while you’re seeing another patient … they can be typing your notes … as you go. (191_GP(Hume))

Wave consulting was considered effective:

… you’ve got a student and a PGY1 who aren’t eligible for Medicare. Then the supervising GP touches base with each of those learners and then there’s a business Medicare transaction. (157_HS(Hume))

Prevocational doctors could also support on-call situations, at restricted scope:

If I’m on-call … I can send the intern over in advance, and he can make sure the line’s in, he’s done the ECG and all those things that you actually don’t get paid for anyway … (191_GP(Hume))

To enable this, these practices set out to assess the prevocational learner’s skills up front:

… [for interns we are] parallel consulting at the beginning … to see where do they ask for help … get that idea as to what is their scope of practice, how much knowledge do they have. (101_GP(Hume))

It also helped to connect RG2s with learning opportunities across the multidisciplinary practice and hospital team: ‘The whole team is the enabler’ (039_GP(Hume)). One health service noted they are creating a multidisciplinary program to support the trainee ‘almost sort of wraparound services’ (157_HS(Hume)) and another reiterated the richness of cross-learning from using other staff, ‘[in doing] meetings with the allied health staff, they understand … that whole multidisciplinary approach …’ (034_HS(BSW)).

Barrier – insufficient doctors to supervise and recruitment and retention issues

A major barrier for some towns was having insufficient fellowed doctors to make supervision possible at the required level: ‘… three IMGs [international medical graduates] at level one supervision, which is the same as an intern supervision, then we are talking about three specialists. Where do I get them?’ (007_HS(BSW)). Another general practice voiced this as a low ratio of fellowed GPs ‘… of that 4.1 we only have 1.6 FTE [full-time equivalent] who are fellowed’ (060_HS(Hume)). The shortage of staff available to supervise meant some communities sought advanced learners with less onerous supervision needs: ‘We take a GPT3 [GP registrar who is in their final year of training] every now and then … because they don’t need to be supervised as much and it takes the burden off the clinic’ (201_HS(BSW)). Extensive effort was dedicated to recruitment to improve supervision capacity, but it often failed or resulted in doctors of inadequate full-time equivalent to supervise: ‘We spent about $20,000 on industry advertising. Guess how many inquiries it netted? Not one inquiry’ (222_HS(LM)); ‘We haven’t been able to recruit, or we’ve been able to recruit but compromise with part timers’ (200_HS(Hume)). International medical graduate and locum use was often the outcome of recruitment failure, but capacity to supervise relied on the doctor’s registration status and the investment of short-term staff in the training agenda.

Retention also affected the stability of supervised training in some areas. They were the result of RGs ‘getting older or effectively semi-retiring’ (200_GP(Hume)). Pivotal RG supervisors who suffered burnout were a major loss to training capacity:

… He was an excellent clinician. He was a GPA [GP anaesthetist]. Everybody loved him … But he said, I just can’t keep working like this. I’m that burnt out. (021_HS(BSW))

Beyond that, the medical workforce turnover in rural general practice was noted to be extreme in some places: ‘[Having lost] 7 GPs in [x] since Christmas … people are driving over 100 kilometres to see a GP’ (067_GP(BSW)). The quality of schooling and available housing was a factor related to doctor recruitment and retention: ‘once we had children and [started] looking at schooling we thought we’d go back to Melbourne’ (101_GP(Hume)).

Enabler – generalist learning opportunities

The wide range of generalist learning opportunities in small towns was an enabler for supervisors to engage with RG2s: ‘[we do] … acute medical or paediatric or post-operative … geriatrics and palliative care … acute respiratory … abdominal and chest pain … Good range to be exposed to’ (009_GP(LM)). Others added, ‘we admit … we do our ward round each day’ (129_GP(BSW). Health services also had a range of generalist learning opportunities: ‘I’ve got two theatres … dialysis, chemo, theatre, acute … plus all your community stuff’ (021_HS(BSW)); ‘… We have an outpatient facility … 24/7 obstetrics service …’ (048_HS(Hume)). Aged and palliative care were other areas offering great learning opportunities – ‘… it’s a huge responsibility and huge learning curve, to look after people in aged care facilities’ (039_GP(Hume) – and providing a wide caseload: ‘We’ve got three nursing homes in the area that we attend … we do palliative care, both at home and in the hospital or the local hospice …’ (116_GP(BSW)).

Enabler – funding for supervision of rural generalists

Funding for supervising RG2 learners was considered an important enabler of quality supervision in rural settings: ‘… I think that if we are really serious about making supervision a priority for these doctors … we do need to fund it’ (067_GP(BSW)); ‘… at the moment we get $120 or $125 an hour for PGY1s. That’s way under what we would earn per hour …’ (101_GP(Hume)). One respondent queried whether Medicare billing item numbers were available for RG2 doctors as was the case under the Prevocational General Practice Placement Program: ‘you’ve still got to see every patient [with] PGY2s … can they get a provider number?’ (039_GP(Hume)). It was also proposed that having ‘a paid position to supervise’ RG2 learners could be enabling: ‘… but funding for that supervision that is almost a supernumerary GP’ (127_GP(BSW)).

Barrier – the cost and risk of supervising

Although the funding was considered enabling, this needed to align with the perceived cost of supervising the RG2 group, in terms of both time and money. Taking on RG2s required busy RG practices to consider ‘how you’d work it out, and how you fund it’ (009_GP(LM)); ‘[for learners] that need one-on-one supervision … it’s too intensive in terms of the busy-ness of the practice …’ (207_GP(LM)). Re-engaging with RG2s was noted to ‘be very, very difficult’ as ‘consulting times would blow out’ (116_GP_(BSW)). One health service executive noted the increased cost impost of supervising RG2s compared with PGY3s because of the effects on the supervisor’s billing efficiency: ‘[the GP’s] not going to smash through 40 people a day … a GPY3 [third postgraduate year] will make it faster …’ (201_HS(BSW)). The capacity to offset the cost of supervising was further limited in rural settings where bulk billing services were needed, ‘… you’re dealing with a rural population who find it really unfair to have to pay gaps’ (101_GP(Hume)), and also hard for smaller practices:

… we’re talking about fractions in tiny, tiny practices – how do you make that financially viable? … someone’s got to take a hit … with paying … [for] … training …’ (222_HS(LM))

Rural hospitals commented that funding could support PGY2 supervision, in line with the funding that follows PGY1s: ‘there are very few opportunities for small rural health services to be funded and supported to train HMO2s and 3s’ (200_HS(Hume)).

Medico-legal concerns and business risks were also noted as barriers to supervising RG2s by health services and practices alike. Some GPs noted that the rural context demanded stronger oversight by supervisors. This related to the RG2’s group’s level of ‘… knowledge and familiarity with working in the community … it could be a medical legal nightmare’ (039_GP(Hume)). The unconscious incompetency of junior doctors was noted for its potential to create ‘a dangerous situation when they don’t know what they don’t know …’ (082_GP(LM)). The possibility they ‘may not be necessarily good at recognising when they need to ask for help’ was enhanced given their enthusiasm (177_BHS(BSW)); but ‘… there’s not quite enough supervisors to make a really safety net …’ (079_GP(BSW)). It was noted that RG2 skills were mismatched with the unpredictable caseload in rural communities and the lack of staff, ancillary services and immediate back-up: ‘… You get your farming accidents, your AMI [acute myocardial infarction] … there’s not an emergency doctor behind you’ (021_HS(BSW)). The impact on an RG2’s career of a negative event could be long lasting:

ultimately it might just be down pumping on that chest for 55 minutes praying to God that they come back to life … You traumatise that PGY2 for life … (201_HS(BSW)

It was widely accepted that, ‘most of the time, nothing bad will happen’; however, this did not allay fear for supervisors questioning:

… if something bad happens … was I really in the room with them when I said I would be? Well, no, I wasn’t. I was saving someone’s life down the hallway … (201_HS(BSW)

One health service executive noted the de-skilling of rural staff as an issue: ‘Our nurses don’t intubate people regularly reliably’ (201_HS(BSW)). The RG2 cohort was perceived as a business risk, having the skill level of a ‘… completely undifferentiated new graduate …’ (116_GP(BSW)). Health services also perceived little to gain from this group: ‘… PGY2 level, it’s not like the health service really gets any benefit from them …’ (048_HS(Hume)).

Barrier – unattractiveness to trainees

Another barrier to RG2 supervision was that the investment in developing accredited training often did not translate into trainees being attracted to these positions ‘even if the GPs are super enthusiastic, all of them, to be supervisors …’ (200_HS(Hume)); ‘There’s a real sense of disappointment for the GP when the potential trainees don’t choose their practice’ (157_HS(Hume)). Some areas were having trouble attracting registrars, let alone more junior doctors: ‘… we can’t even attract, in the last couple of years, registrar placements’ (207_GP(LM)). The lack of succession outcomes from training also impacted on the supervisor’s enthusiasm:

You know, it’s hard to year after year after year, train people to have them leave … [over] about six to seven years … every registrar that we trained … every one of them left. (039_GP(Hume))

The financial squeeze on rural general practice was also thought to make rural training unattractive to trainees as was the breadth of practice, ‘… doctors in this generation don’t want to do that’ (021_HS(BSW)), and the rural lifestyle was not necessarily attractive to junior doctors: ‘It can be very difficult because there is no social life’ (226_GP(LM)).

Enabler – coordination and case management

Investing in coordination and case management was considered important to enable independent health services and practices in Victoria’s different towns to work together for supervised generalist training:

Enablers would … be someone like the VRGP coordinating that … [it is] a massive amount of … time … organising all the different learners … [and the] different requirements and rules (191_GP(Hume))

This was echoed by a health executive: ‘The model I’ve described to you is actually an enormous amount of work on a small rural hospital to put in place’ (133_HS(Hume)). Case management of trainees is an important part of the solution to match learners to relevant supervised training in Victoria: ‘I’ve seen [VRGP staff] doing incredibly successful case management of junior doctors’ (157_HS(Hume)). Practice managers, Regional training networks and the PMCV were also seen as important coordination entities: ‘… a massive amount of our practice manager’s time is organising all the different learners and [their] different requirements and rules …’ (191_GP(Hume)); ‘I started having conversations with PMCV … [to build up] an internship program …’ (007_HS(BSW)).

Barrier – reliance on rotational staff

A final deterrent to supervising RG2s was that rural towns were using rotational staffing models, including learners who were not necessarily dedicated to the area:

The hospital increasingly employs [doctors] who just rotate in and out of here … it’s not helping us, and I think our practice would have a low [level of interest]. (207_GP(LM))

Supervisors were interested in trainees who were committed to the region, of whom they saw few ‘… on a pathway to long-term commitment to our town’ (207_GP(LM)). Additionally, the use of locums and fly-in fly-out staff did not provide a consistent supervisor base:

… for [x], they basically have a fly-in fly-out GP workforce. I don’t think they have enough onsite consistency to supervise someone to the degree that I would be comfortable with. (110_BHS(LM))

and, while one respondent noted some locums have ‘a keen interest in teaching’, this was clarified as being ‘probably the exception rather than the rule’ (200_HS(Hume)).

Rotational hospital staff also made it hard to designate a continuity of supervision:

We’ve got … areas where the supervisors are not rotating so people can have a designated supervisor, but they’re not always rostered … continuity is a challenge. (177_BHS(BSW))

Discussion

Building supervised training for prevocational learners across a generalist scope in distributed rural communities is a complex undertaking given the many diverse enablers and barriers at play. These may intersect in different ways in different communities; however, as aggregate findings, they suggest that supervised learning needs to be addressed at multiple levels of the system, the community, the clinical settings and the clinicians. The factors affecting supervised learning for RG2s are a lot more complex than described in previous research, which was centred on enabling rural GPs to supervise registrars13. Such papers mainly dealt with the general practice component of supervision for registrars in a general practice alone and not the nuance of supervising RG2s across a range of community services, at generalist scope, involving complex and unpredictable caseloads. The complexity found in this study also stems from supervising learners at the prevocational stage, their level of perceived competency, and the capacity to safely fit them into a large workload of RG doctors without affecting personal livelihood or reputation, while maintaining patient wellbeing. This occurred in environments that may be very stretched for resources and are therefore supervising RG2s was regarded warily given the potential for something to go wrong. Unlike registrars at advanced stages of general practice training, the RG2 learners were rightly or wrongly viewed as a highly variable cohort unfamiliar with the context and likely to need full-time oversight or, at minimum, thorough vetting before they joined the business.

On a positive note, a wide range of factors were noted to enable supervision of RG2 doctors. Among these were supervision teams, inclusive of multidisciplinary models where PGY2 learners were able to stretch themselves. Practices that had wide experience of supervising interns, particularly those familiar with RG interns, were able to highlight a range of viable methods for building RG2s into the practice model, including getting their assistance with notetaking, working up patients, and wave consulting to generate billings. Many noted that funding models for supervision should be given considerable focus to ensure supervision is viable in rural practices with small full-time equivalents, reliant on mostly bulk billing (due to community needs) and with long waiting lists.

Staffing shortages prevail in rural areas and may have a major impact on supervision capacity, particularly when many practices are already supervising overseas-trained doctors, as is common in rural areas, at level 1 supervision (overseeing every encounter). Similarly, rural areas that built accredited training and experienced failed recruitment were de-motivated to supervise. Burnout is a major issue, not necessarily related to supervising, but the overall workload as an RG. Burnout impacts on the retention of RGs, and supervision can contribute to RG burnout, highlighting the importance of structuring supervision to be sustainable for the doctors in a town, particularly those in small practices.

While rotational workforce systems including locums may offer a solution for workforce shortages, regions reliant on these systems are potentially moving farther away from developing their local health workforces because the very nature of locums undermines stable supervision capacity for RG training. One way to transition these regions to 'grow your own' might be to adopt innovative supervision models using roving supernumerary clinical supervisors that would add immediate capacity to the multidisciplinary team models on the ground. Remote supervision models have been described but may require some adaptation to fit with RG2 supervision needs33, including having a level of onsite supervision and clear demarcation of roles and responsibilities between onsite and offsite supervisors.

The aggregate findings suggest that expanding supervised learning for the RG2 step in the RG pathway will require a longer-term build, including convening regional networks to discuss the implications of the findings in their own region. They will also need to consider pockets of strength that can be a starting point for expanding RG2 supervision, perhaps starting with practices familiar with the intern group and locations that are more attractive to learners. The latest iteration of the Prevocational General Practice Placement Program, the Rural Junior Doctor Training and Innovation Fund program may also require more explanation for practices to understand what it offers, along with the VRGP explaining the quality and regional commitment of the RG2 group – so that they are seen as worth supervising. While the VRGP offers coordination and case management, further collaborative resources may be needed to invest in capacity building for supervision at the RG2 level. The findings of this project have been applied to develop a supervision roadmap, which will be applied to ongoing planning of RG training through the Regional Networks in Victoria34.

This research has some limitations. Participants were unfunded and the research relied on a purposive sample invited to participate over a tight timeframe during the COVID-19 pandemic. There is the chance that there was selection bias towards those with extreme views; however, the study achieved a varied sample, which resulted in broad perspectives making the research more widely applicable to the shared decision-making around RG2 supervision that is common in Victoria’s rural communities. It is worth noting that further saturation of the findings may have happened if more focus was placed on one type of stakeholder, such as GPs. Although this study had limited individual stakeholders responding, the respondents were able to talk about their whole health practice context and community. Further, this study achieved a strong response rate given how busy rural health services and doctors are, especially in the context of the pandemic. Caution should be exercised in applying these findings to rural settings outside of these regions, as the data are only indicative.

Conclusion

This research sought to explore the enablers and barriers to the supervision of RG2 learners across a core generalist curriculum in distributed towns in three rural Victorian regions. The findings denote that such supervision capacity is complex to mobilise at the RG2 step, and is affected at many levels of the system, including recruitment, retention and the workload and responsibility that RG doctors carry in small rural communities. It is also affected by the viability of practices and their capacity to offset the costs and risks of supervising more junior doctors. Supervision for the RG2 level could be expanded by focusing on practices with critical mass, models of supervision that help RG2 learners to support practice efficiency, and using opportunities for these doctors to learn from the wider team. Supervision can also be enabled by funding for supervision along with case coordination and management. Finally, it may rely on building up a vision about the value of the RG cohort and their intentions to stay in the region. Developing supervision capacity should be viewed as a long-term undertaking, which requires regional commitment and stepwise planning. This is going to be imperative in achieving engaged and skilled RG trainees to serve Victoria into the future.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded through the Regional Networks of the Hume, Loddon Mallee and Barwon South West through a Victorian Department of Health Training and Capacity Grant. The authors acknowledge the traditional custodians of the lands on which this work was conducted. They acknowledge the participation of a wide range of stakeholders who generously gave of their time for this project.

References

appendix II:

Appendix II: Training requirements for postgraduate year 2 level doctors depending on their status

You might also be interested in:

2014 - Mount Isa Statement on Quad Bike Safety

2013 - A national study into the rural and remote pharmacist workforce

2010 - Health worker effectiveness and retention in rural Cambodia