Introduction

The early stages of telemedicine

‘Telemedicine involves the use of telecommunications and virtual technologies to provide health care outside traditional health facilities,’ according to WHO1. Examples of telemedicine include virtual health care at home, where patients such as those who are chronically ill or elderly can receive support in some circumstances without leaving their homes. Remote consultation can be useful to reduce patient visits to clinics during a pandemic, and it facilitates communication between healthcare professionals in remote environments.

A 2005 survey by WHO revealed that teleradiology, teledermatology, telepathology and telepsychiatry were the first available applications of telemedicine1. In these ways the sustainability of health care could be supported by telemedicine2,3.

The use of telemedicine devices in daily practice seems imminent, but issues with privacy, security and quality of service are still to be resolved4-6, and it is imperative that medical students receive adequate training in e-health7. This is particularly relevant in countries with widely dispersed populations where telemedicine has the potential to address many of the key challenges in providing health care8. Before the recent SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic, some published literature indicated a skepticism about the use of telemedicine on a large scale, as there were issues in the domains of policy, funding priorities, and education and training. These authors suggested that it was ‘quicker, easier and more cost-effective not to use telemedicine’9.

Telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic

With the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was an urgent need to adopt new strategies10; teleconsultation solutions already used in previous epidemics, such as Ebola and SARS, were boosted11-13 and gained even more visibility14,15.

Teleconsultation can address the aim of reducing the level of contact among people to prevent cross-contamination and avoid the spread of coronavirus. Nevertheless, the goal of teleconsultation is also to continue providing patients, infected by COVID-19 or not, with medical support11,16-18. For the effective implementation of remote consultations as a modality of health care within a health system, it is important to examine how it is perceived by healthcare professionals, as this could have an impact on its effectiveness19,20. So far, little is known about the changes in consultation in European rural primary care settings during the COVID-19 pandemic11,21-23.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on changes in patient consultation in European rural primary care as well as national regulations for these consultations. The authors hypothesized that the pandemic changed the tools and types of consultation in each country.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study was based on a key informant survey from 16 member countries of the European Rural and Isolated Practitioners Association (EURIPA). EURIPA operates under the umbrella of WONCA (World Organisation of National Colleges, Academies and Academic Associations of General Practitioners/Family Physicians).

Procedure

The steering committee of this project, called the EURIPA Covid-19 study, developed a semi-structured questionnaire with 68 questions, 21 of these including free-text comments.

The first draft of the questionnaire was based on the research objectives through an extensive literature review. Subsequently, a panel of five primary healthcare experts and one methodology expert used a Delphi process to evaluate the validity of the items and the length of the questionnaire, formulate suggested changes and identify missing items. The research team then discussed all feedback until consensus was reached, and a second version of the questionnaire was developed.

Validity

The psychometric properties of the questionnaire were assessed both quantitatively and qualitatively, focusing on validity as a theoretical construct and as an empirical construct. With regard to validity as a theoretical construct, eye validity and content validity were tested. During the development of the questionnaire, eye validity (whether the questionnaire measures at first glance what it purports to measure) and content validity (whether the items adequately represent the entire domain that the questionnaire attempts to measure) were tested. In each case, this was done by EURIPA primary healthcare experts, all international authorities in the field of health care. Construct validity (the extent to which the items in the instrument relate to a relevant theoretical construct) was improved by using the results of the scoping review as the theoretical basis in the first step of the development process.

The informants were contacted directly via email by the national coordinators, and the response rates were all above 50%. The optional free text was analysed to extract the reasons for the non-uniformity of the responses and discrepancies between the official rules on teleconsultation, if any, and the responses from key informants.

Participants

Primary care providers (PCPs), mainly general practitioners, from 16 European countries agreed to participate in this survey.

A convenience sampling technique was used whereby national coordinators (members of EURIPA International Advisory Board) chose informants from different geographical regions within their own country. The informants were contacted directly by the national coordinators; they were required to be PCPs (any professional working in primary health care, such as a doctor, nurse, physiotherapist or assistant) with a good command of English, as the survey was written in English and was not translated into the national languages. The informants were all practising PCPs and were asked to give the general view of the attitude of PCPs in their country.

Because a convenience sample of informants was used, the PCPs for each country may not be representative, although there was an attempt to achieve geographical variation. The national coordinators tried to avoid bias and to recruit practising PCPs with different interests, and not necessarily in telemedicine. The questionnaire was refined after a first pilot study. The authors cannot rule out the possibility of confounding or alternative explanations to results, since the survey responses show attitudes and not actual performance. Participants with complete data could not be distinguished from the less than 10% of participants with incomplete or missing data that were then considered as ‘missing completely at random’ (MCAR) data. The complete case analysis method was used and all participants with incomplete data were removed from the analysis.

Study size

When the number of informants reached or exceeded 30 for countries with 35 million or more inhabitants, and 20 for countries with less than 35 million inhabitants, data collection for that country was terminated.

Main outcome measures

The questionnaire included 68 questions (21 of which were based on free text), including sociodemographic variables, length of clinical experience and experiences of COVID-19 pandemic management and geographical location (Supplementary table 1), either rural, semi-rural and urban areas. The questionnaire was divided into several sections. This article reports on analysis of the questions related to patient consultation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Other sections of the questionnaire will be analysed in the future.

Analyses

To describe baseline characteristics, proportions were calculated for dichotomized or categorized data, and means were calculated for continuous data. Pearson’s χ2 test was used to measure the association between categorical variables. One-way ANOVA and the two-tailed student t-test were used for continuous variables such as age and seniority (length of experience) while non-parametric tests such as the Kruskal–Wallis test were used for ordinal numeric variables. The statistical significance threshold was set at 0.05. Multivariate analysis by logistic regression model was used to assess the association of multiple variables.

Statistics were conducted using IBM SPSS v27 (https://www.ibm.com/software/shopzseries/ShopzSeries_public.wss). For open questions, as the responses were limited to short sentences, a brief conceptual content qualitative analysis was carried out. Responses (direct quotes) from PCPs were independently reviewed by two members of the research team (DK, OG).

Ethics approval

The responses of respondents were collected anonymously; no formal approval from an ethics committee is required in the countries involved in the survey.

The informants were aware that they could withdraw at any point. Informed consent was received. Confidentiality and anonymity were assured. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Participants

Questionnaire respondents were collected from 406 PCPs in 16 European countries; 245 respondents (60.5%) were females and 160 (39.5%) males. Regarding location of the practice, 152 PC informants were rural (37.5%), 124 semi-rural (30.5%) and 130 urban (32.0%).

Descriptive data

Overall mean age of the respondents was 45.9 years (standard deviation (SD) 11.30) while their average seniority was 18.2 years (SD 11.6). Three hundred and eighty-one (93.8%) respondents were medical doctors; other disciplines (nurses, medical registrants, managers, social workers, midwives, dentists, physiotherapists) accounted for only 24 respondents (6%).

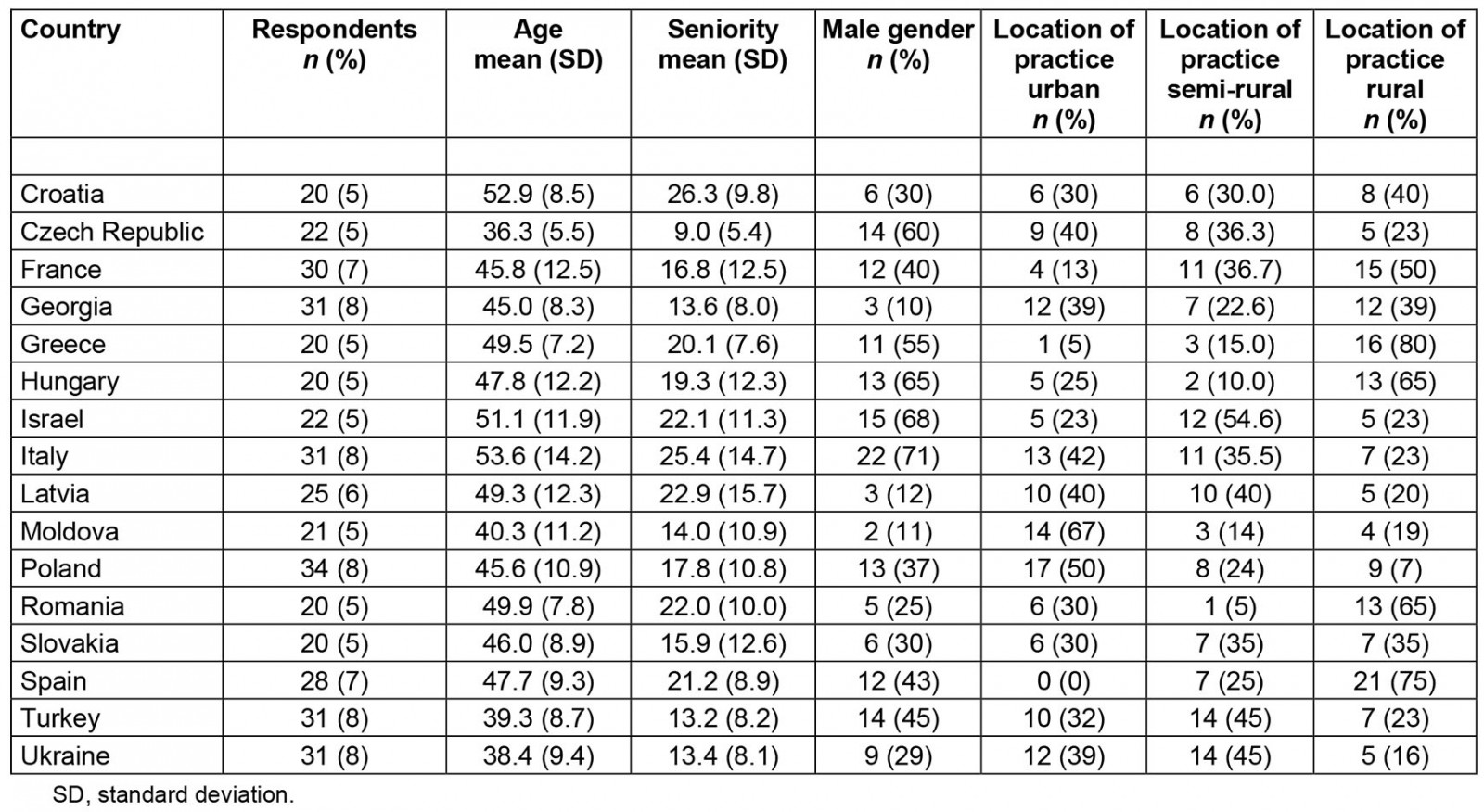

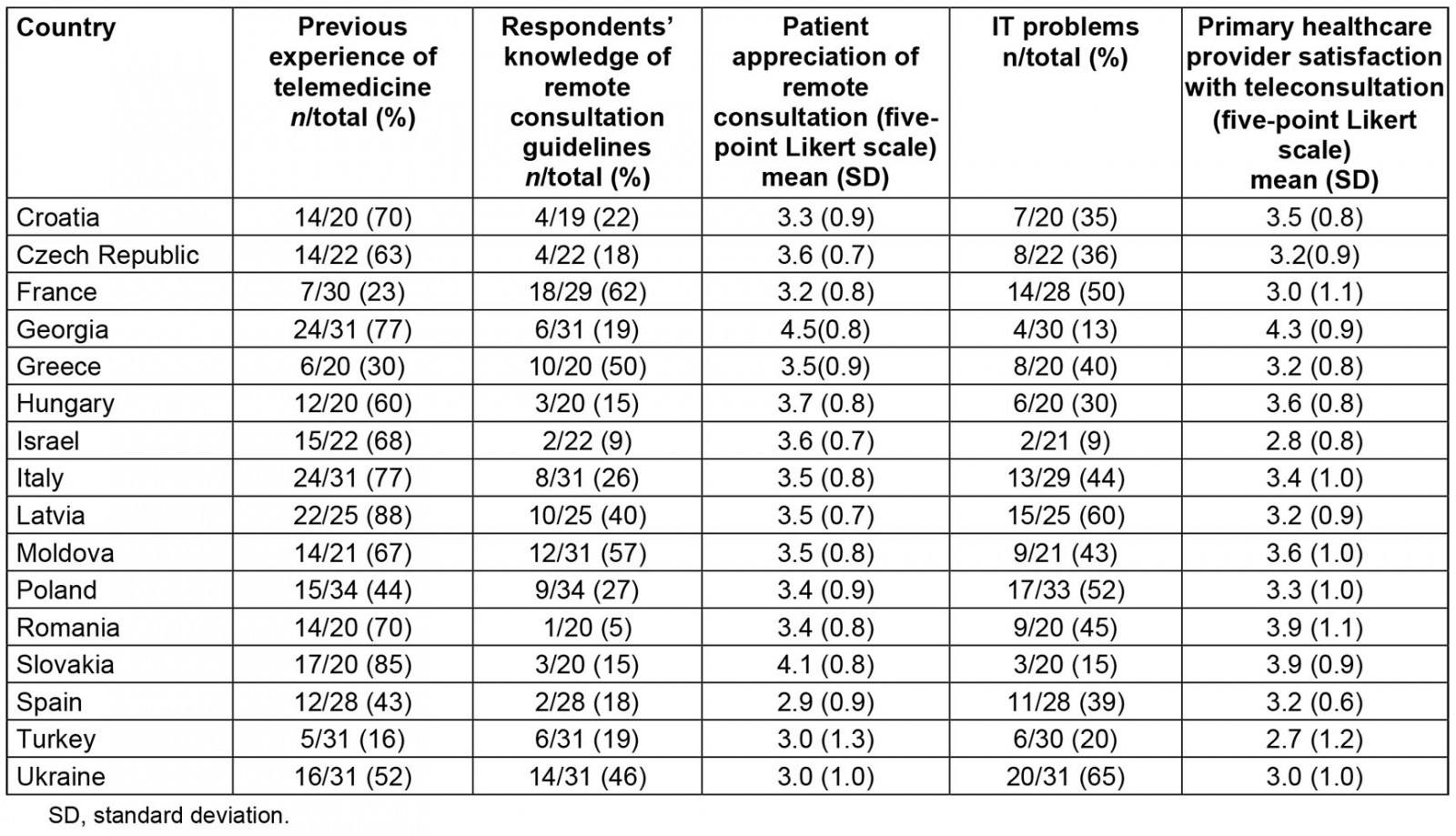

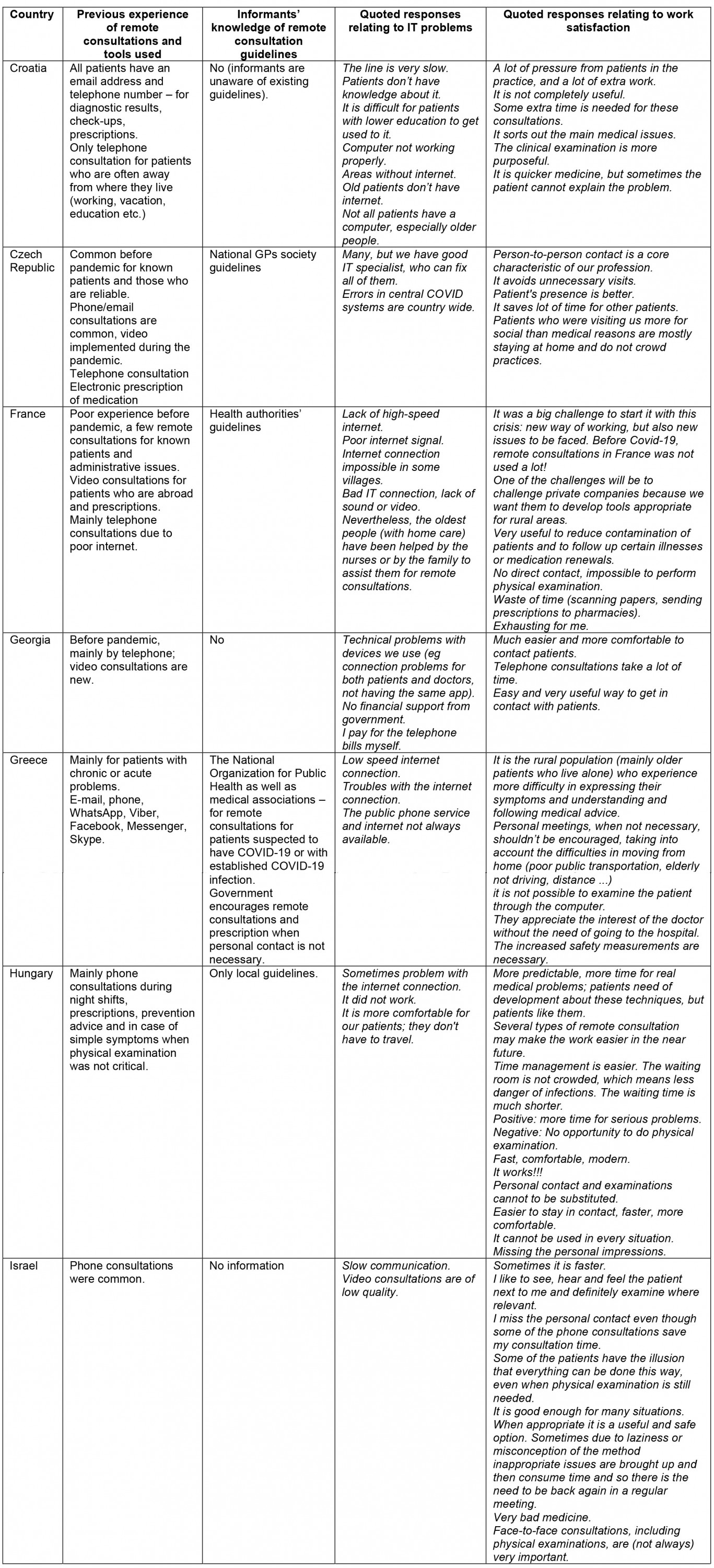

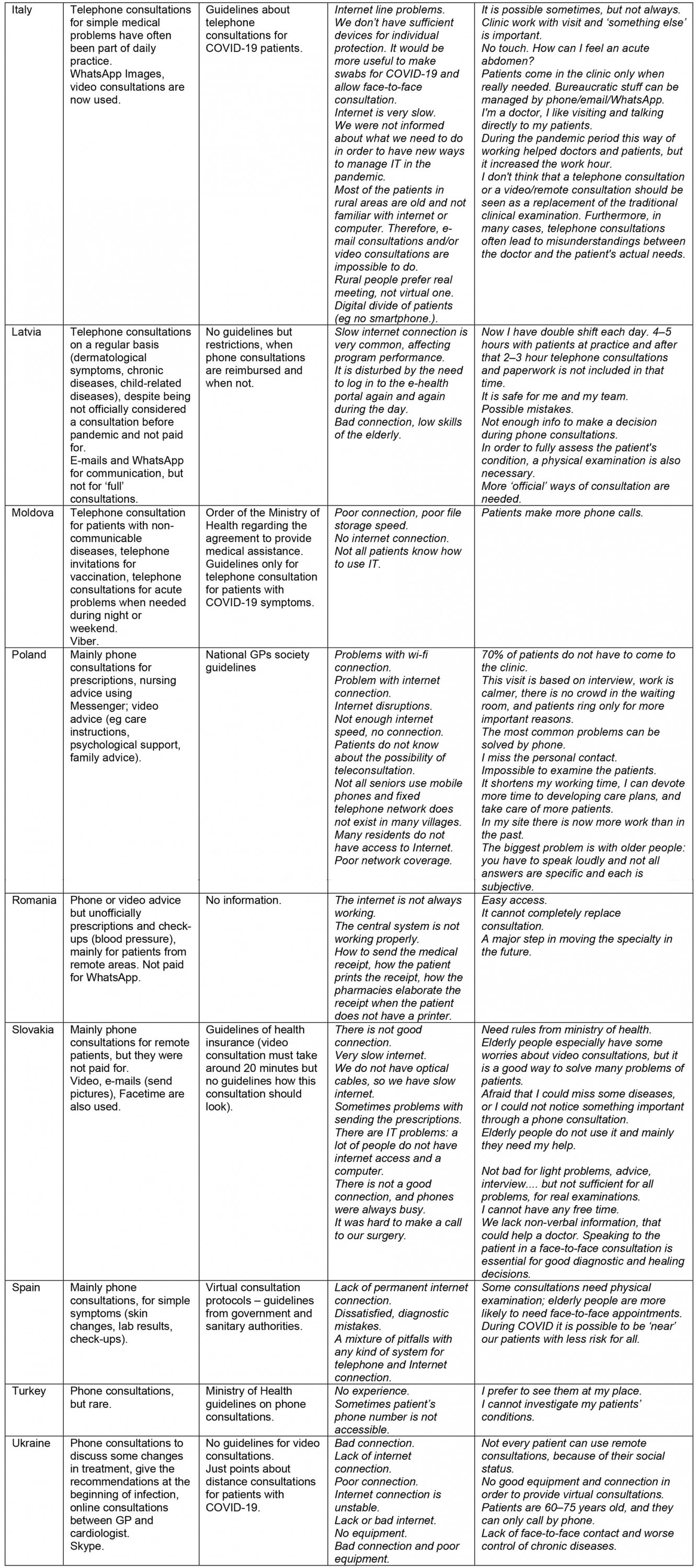

The baseline characteristics of the informants divided by countries and some descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1 while the responses of the informants are presented in Table 2.

The questions were about previous experience of telemedicine, the respondents’ knowledge of remote consultation guidelines, the presence of internet issues (lack of broadband or unreliable internet connection) and the appreciation of new types of consultation by both patients and PCPs. There were considerable statistically significant differences between countries again. According to the informants’, previous experience in remote consultation varied from 88% (22/25) in Latvia to 16% (5/31) in Turkey. Regarding the respondents’ knowledge of remote consultation guidelines, the positive responses varied from 62% (18/29) in France to 9% (2/22) in Israel. Internet issues were stated by 65% of the respondents in Ukraine (20/31) but only by 9% (2/21) in Israel. According to the respondents, both patients and PCPs like these alternative methods to face-to-face consultation, with only Spain scoring less than 3 in the five-point- Likert scale average for the ‘patients’ appreciation of teleconsultation’.

It is important to note that collected information relates to the respondents’ perception of patient appreciation of teleconsultation and not the true patient appreciation of teleconsultation; no patients were interviewed. PCPs’ satisfaction with remote consultations was above 3 in all the countries apart from Israel (2.8, SD 2.8) and Turkey (2.7, SD 1.2). However, even for PCPs satisfaction, the differences between the individual countries are significant.

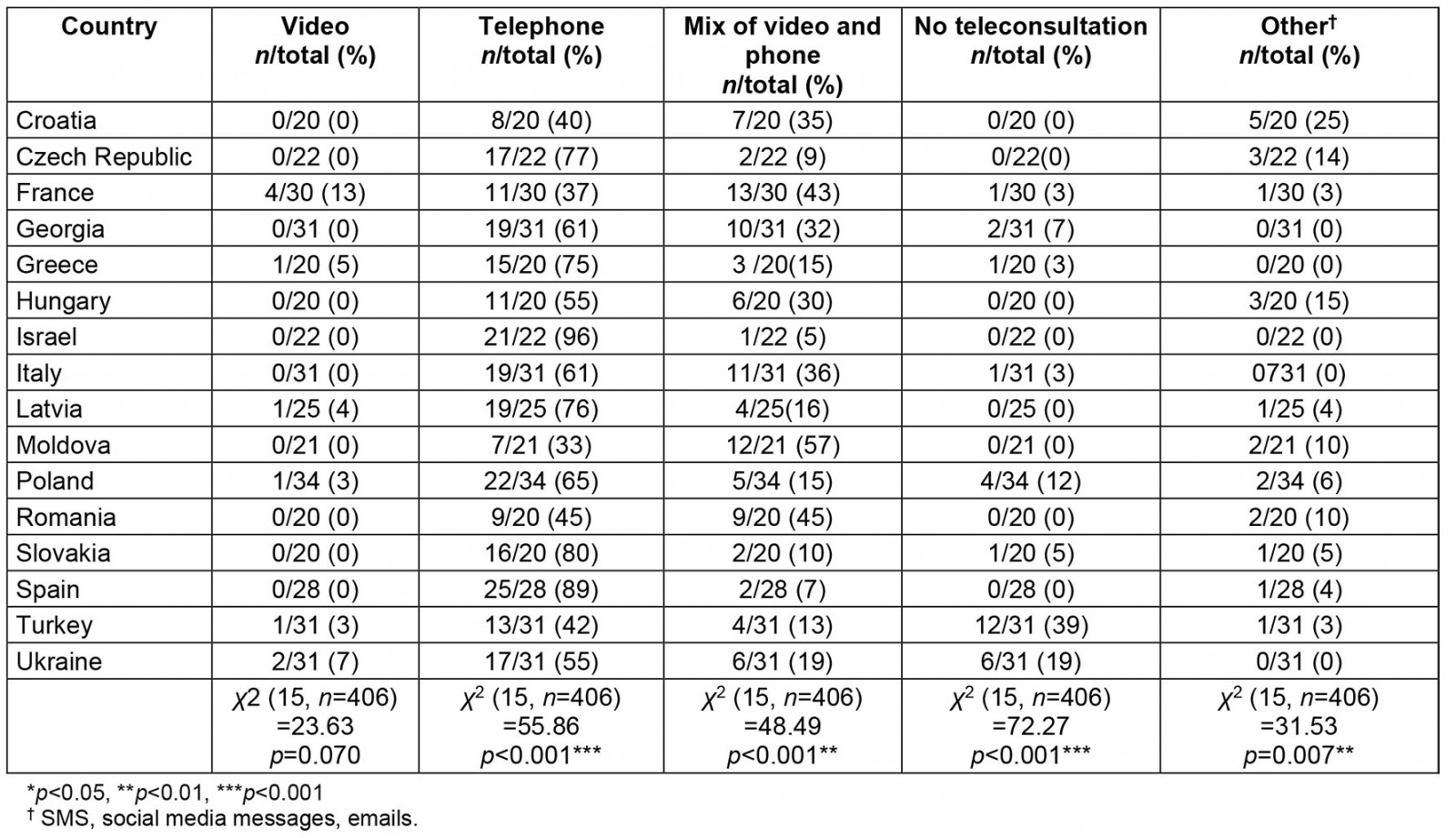

There were considerable differences between countries in the adoption of the different types of consultation by informants, and these differences were statistically significant. Video-consultation was mentioned as the preferred type of consultation for the 13% of the informants in France (4/30) but no informants at all in Croatia, Czech Republic, Georgia, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Moldova, Romania, Slovakia and Spain stated that they prefer a video consultation. Telephone consultation was the preferred type of consultation for 96% of the respondents in Israel (21/22), while the lowest appreciation of telephone consultation was found in Moldova 33% (7/21). The preferred types of consultations are summarized in Table 3.

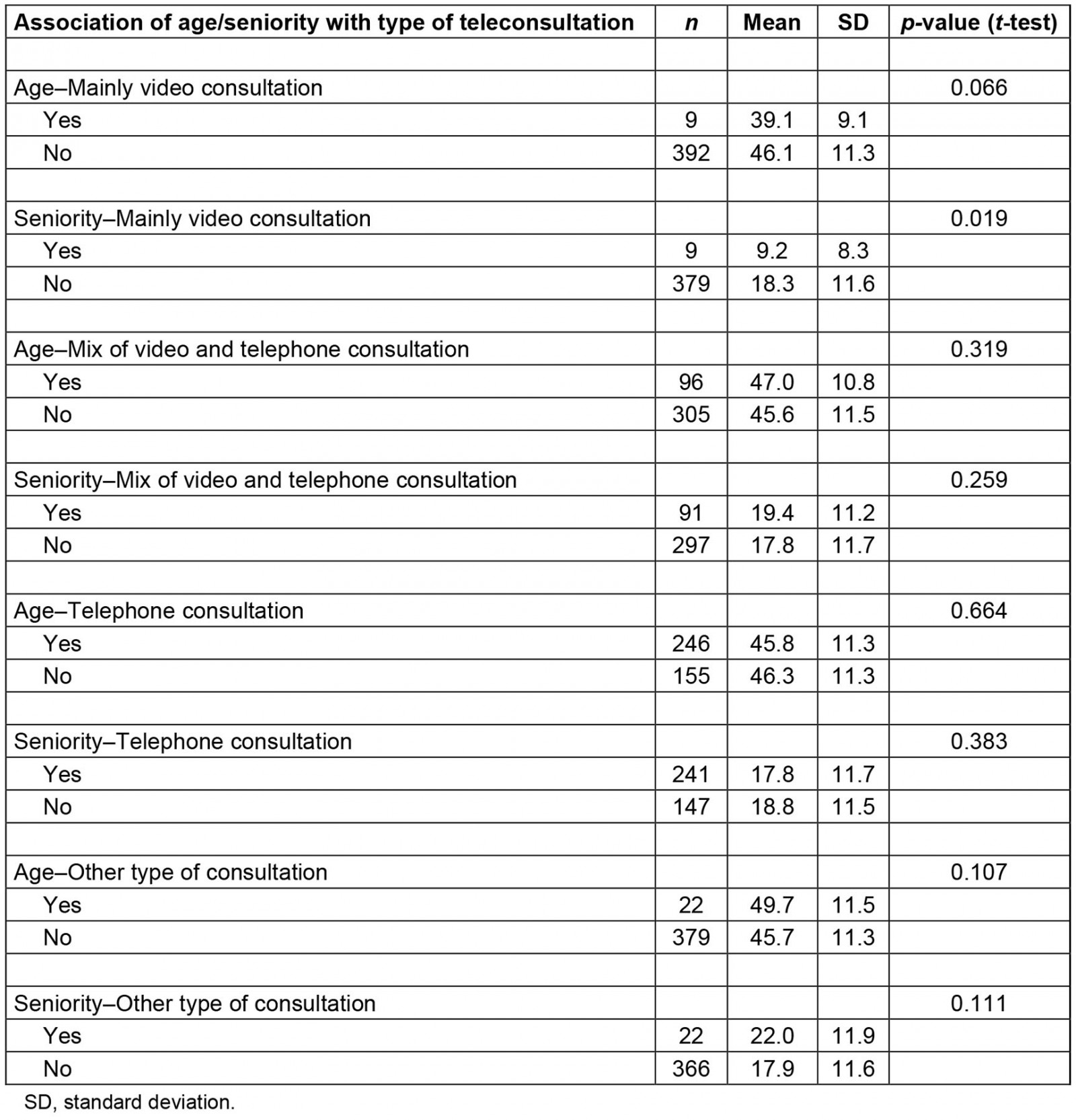

Only seniority seems to have a statistically significant association with video-consultations: less senior people were more likely to adopt video-consultation, while all other associations were not found or the difference between the two groups, although relevant, did not reach a statistical significance, as it was for age and video-consultation.

No statistically significant association was found between gender and attitude to adopt video-consultation and on the level of PCPs satisfaction. The same applies for the site of practice (rural, semi-rural, urban).

Logistic regression including age, gender, site of practice, seniority, IT issues, previous experience of remote consultation and respondents’ knowledge of remote consultation guidelines confirmed that the only factor significantly associated with the adoption of video-consultation was seniority (inverse relationship) of the PCP (OR 1.19, 95%CI 1.02–1.40, p=0.03). Finally, age, gender and seniority of the informants were checked for an association with the preferred types of consultation. The outcomes are shown in Table 4.

Table 1: Respondent characteristics

Table 2: Questionnaire responses

Table 3: Types of preferred remote consultation in study countries

Table 4: Association of age, seniority and gender of respondents with preferred type of remote consultation

Analysis of answers to open questions

Table 5 summarizes the free-text comments of the informants.

Table 5: Summary of data from open-ended questions

The respondents usually used telephones before the pandemic (‘especially in a flu pandemic’, ‘mainly during night shifts’) and they mentioned that ‘now it is legal’ and ‘can also ‘examine’ patient through phone, video or email (send pictures)’.

Especially in rural settings, it ‘is difficult for my patients to come to my practice so often I offer ‘phone or online consultations’ and ‘… all [patients] have my e- mail address and telephone number’.

The phone consultations were used for ‘reporting of diagnostic results and health status, follow-up, prescriptions, prevention advice, nursing advice using Messenger, care instructions, psychological support, telephone invitations for vaccination’, and respondents were ‘receiving questions, videos, photos from the patients on WhatsApp before the Covid19 pandemic. Photo (eg skin problems) and audio consultation (eg in case of simple diarrhea)’.

The IT problems could be classified as ‘lack of internet/electricity/devices/applications’, ‘lack of knowledge about the consultation process from both sides (patient and physician)’ and ‘payment of IT/ phone bills’. Although phone and/or video consultations saved time, in some places not only patients but also physicians couldn’t use this opportunity. Physicians and nurses helped elderly patients to use devices in some settings.

Work satisfaction has new dimensions among physicians: ‘clinical examination’ seems more purposeful while physicians felt under pressure from patients. This process is ‘avoiding unnecessary visits’, it is ‘good as keeping a kind of overview in quarantine times, but not suitable for all the medical conditions and for all our patients’, and ‘very useful to reduce contamination of patients and in the follow up of certain illnesses or medication renewal’. Also, ‘it is much quicker medicine, but sometimes, the patient cannot explain the problem’.

One of the challenges could be for elderly people and/or living in rural areas:

… to challenge private companies – because we want them to develop tools appropriate for rural areas.

Also:

… it is the rural population (mainly older patients who live alone) who experience more difficulty in expressing their symptoms and understanding and following medical advice.

Some conclusions from respondents on remote consultations were:

Positive: more time for serious problems.

Negative: no opportunity to do physical examination.

Sometimes it's faster but it would be great if I could examine the patients. And because I'm new a lot of patients don't know me and don't trust me on the phone.

I don't think that a telephone consultation or a video/remote consultation should be seen as a replacement of the traditional clinical examination. Furthermore, in many cases telephone consultations often lead to misunderstandings between the doctor and the patient's actual needs.

I do not have good equipment and connection to provide virtual consultations, also a lot of my patients are 60-75 years aged, they can only call me by phone.

I'm a doctor, I like to visit and to talk directly with my patients.

Guidelines on remote consultations

Regarding the respondents’ knowledge of remote consultation guidelines, respondents reported guidelines only for COVID-19 patients, mainly prepared by local authorities and in some countries, such as Slovakia, by health insurance companies. Some respondents raised the issue of a high level of complexity of these guidelines: ‘I did not read’ and ‘It’s very long’. This should be considered in the development of future guidelines suitable for primary care.

Discussion

Principal results

Many differences between countries on the level of adoption of remote consultation have been found in this study. Significant differences between countries were also found in adopting alternative arrangements for face-to-face consultation: remote teleconsultation is well appreciated by both healthcare professionals and patients, but the most common way of remote consultation remains telephone consultation. A factor significantly inversely associated with the adoption of video consultation was the seniority of the PCP.

The difference between countries may be explained because most countries in this study have not created a regulatory framework to authorise and integrate telemedicine into their national health systems, including during emergency and public health outbreaks24. Unlike countries with a capitation system policy, those with a different remuneration scheme, for example fee for service, need to adopt rapid change in their reimbursement policies. In the USA, the use of Skype, Zoom, Google Hangouts, Apple and telehealth visits has been authorised and reimbursed at the same rate as face-to-face visits since 1 March 202025. In France, patients have been reimbursed when using telemedicine solutions since September 2018; in March 2020, due to the COVID-19 crisis, the French government issued a decree allowing French health insurance to cover any medical teleconsultation24. Health authorities in many other countries have implemented telemedicine user guidelines to incentivise people to use such services during the COVID-19 pandemic11.

The present study confirms that although during the pandemic most doctors changed their clinical attitudes, most of them rely on the most traditional alternative to face-to-face consultation, telephone consultation, which accounts for an average of 61.3% (249/406) consultations, varying from 33% (7/21) in Moldova to 96% (21/22) in Israel. A mixture of video and telephone consultation is also quite popular at 24% (97/406), but again there is great variation between countries, from 5% in Israel (1/22) to 57% (12/21) in Moldova. A mixed-methods longitudinal study in the UK in 2020 during the pandemic21 found that consultations were administered in 89% of the cases by telephone while only 1% were coded as video, increasing to 3% for patients aged more than 85 years. Fewer than 1% of consultations coded by GPs were e-consultations via email.

Video consultations alone were not so popular in the present study, accounting for only 3% (10/406) of the total respondents. In France, 13% (4/30) of the respondents are in favour of video consultation alone while in many other countries (Croatia, Czech Republic, Georgia, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Moldova, Romania, Slovakia and Spain) no respondents are in favour of video consultation alone. This is in line with what was found by other authors26; a qualitative study conducted in Spain showed that even though 83% of the interviewed informants had not conducted a video-consultation, they considered it to be an adequate option for health care (96.2%). In the UK, telephone consulting is widespread but, prior to the pandemic, video-consultations were very rare27,28 and the success of e-consultations was low but increasing29,30.

Only a few respondents seem to refuse any alternative to face-to-face consultation with no respondents at all in many countries (Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Israel, Latvia, Moldova, Romania and Spain), while Turkey seems to be the most traditional country: 12/31 respondents 285 (39%) are against video-consultation. This is in line with what has been found by other researchers26-28 where the increasing success of remote consultations has been highlighted. Other ways of remote consultation, including mobile SMS, social media messages and emails, account for only 5% (22/406) of respondents, ranging from 25% (5/20) in Croatia to 0% in Georgia (0/31), Greece (0/20), Israel (0/22), Italy (0/31) and Ukraine (0/31). In a British study, the consultation rate for GP-to-patient only using SMS messages was also very low21.

The factor that seems more related to the adoption of more sophisticated ways of remote consultation such as the video consultation is seniority – those who are less senior are more disposed to adopt video-consultation as a reliable alternative to traditional ways of consultation. A Catalan study, carried out before the pandemic, confirms that the youngest professionals, under 40 years of age, are more likely to be intermediate or advanced users of technology4.

Special educational programs should be implemented to increase e-health competencies both in patients and family doctors.

In the present survey, 56.9% (231/406) of respondents declared previous experience of remote consultations.

Remote primary care consultations, conducted mainly by telephone, video, or through asynchronous text-based GP–patient communication via email or mobile SMS had started to become more and more prevalent before the pandemic21. In Denmark, GP telephone triage and patient emails were already standard practice before the pandemic31, and the US Kaiser Permanente has been offering secure GP–patient email communication and routine telephone/video consultations for many years32.

Internet issues were reported on average by 38.2% (152/398) of respondents; these issues were stated only by 10% (2/21) of respondents in Israel but by 65% (20/31) in Ukraine and by 60% (15/25) in Latvia, two countries with a high rural population. Surprisingly, IT issues were also raised by 50% (14/28) of French respondents. In a recent British study, GPs declared varying levels of IT problems with video-consultations and while some GPs had high expectations of video calls, as the pandemic declined others felt that face-to-face consultation was increasingly preferable to video-consultation for patients who needed visual assessment21. Regarding this issue, some authors are very concerned about equity: video-consultation will increase access for those with good IT skills, but it will increase the already existing health inequities28,33. Increasing the availability of new tools thatrequire sophisticated infrastructures, without investing adequately in rural and dispersed areas, will inevitably lead to an increase of inequity. Fortunately the countries with a fee-for-service reimbursement scheme that did not previously reimburse remote consultation have all taken urgent measures to change this scheme; however, this problem is far from being completely solved.

Limitations

This was a small-scale, mixed-methods study and there could be limitations related to the transferability of these findings. Nonetheless, the aim of addressing healthcare professionals’ perceptions about the implementation of remote consultations in their daily clinical practice was achieved. Because a convenience sample of informants was used, the PCPs for each country may not be representative, although there was an attempt to achieve geographical variation. The national coordinators tried to avoid bias and recruit practising PCPs with different interests, and not necessarily in telemedicine. Because this is a survey of key informants, the authors could not fully assess the representativeness of the sample. However, to get the most accurate picture of selection bias, all researchers kept a detailed log of selection and recruitment strategies in their country. The sample is also compared as closely as possible with the national population of GP practices.

The questionnaire was refined after a first pilot study. However, it was not validated against other measures apart from a face validation procedure. The authors cannot rule out the possibility of confounding or alternative explanations to these results, since the survey responses show attitudes and not actual performance. However, the results align with the outcomes of previous studies4. The study did not explore the patients’ points of view directly but only what was reported by PCPs. Future studies will be needed to explore patients' views on teleconsultations during the pandemic and verify whether these attitudes will tend to change rapidly or persist once the pandemic is over.

It is important to note that differences in the number of answers to each of the questions, the online questionnaire and the selection process may be a source of independent biases in generalizability of the results.

Conclusion

The study respondents identified both positive and negative aspects related to remote consultations and the difficulties associated with their implementation. Both PCPs and patients have rapidly adapted to this alternative to face-to-face consultation, although most of them prefer the most traditional way of remote consultation: telephone consultations. The less senior PCPs are more likely to adopt more sophisticated ways of remote consultations so it is likely that in the near future video-consultation will become more successful. A digital divide is still a major concern and, apart from a few exceptions, Internet issues were claimed by a considerable number of informants both in urban and rural settings. Legal, ethical and regulatory issues should be addressed by health authorities for an effective remote consultation implementation.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks are also due to all PCPs across Europe who actively collaborated in responding to the survey.

References

Supplementary material is available on the live site https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/7196/#supplementary