Introduction

In their landmark report Primary health care – now more than ever, WHO acknowledged the vital importance of primary care in tackling global health problems and urged significant investment in the health workforce1. Despite this, there is still a concerning shortage of primary care providers in both developed and developing countries around the world, particularly in rural areas2.

In the UK, general practitioner (GP) workload has grown in volume and complexity due to an increasing rate of multimorbidity, an ageing population and work being increasingly moved from hospitals to primary care3-5. This increased GP workload, combined with a shortage of GPs due to recruitment and retention issues, has caused a crisis in the general practice workforce6,7.

Poor retention of GPs is a complex problem. Recent data in Scotland show the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) GPs decreased by 160 in just a few years, from 3735 in 2013 to 3575 in 20178. GP numbers are declining as more GPs are leaving to take career breaks, work abroad or retire early9. Although there are many reasons why GPs are leaving general practice, including the increasing workload, financial issues and fears of litigation, job satisfaction is considered the main predictor of GP retention9-11.

Many individual factors are associated with increased GP job satisfaction including variety of work, workplace autonomy, satisfaction with colleagues and recognition for work12,13. Certain practice characteristics have been linked to increased job satisfaction, including a good workplace culture and coordination with secondary care14,15. Many factors are associated with decreased GP job satisfaction, including renumeration, hours of work, administrative tasks and poor physical working conditions15,16. Job stress is associated with decreased job satisfaction, and poor physical and mental health of physicians12,17. This in turn makes GPs more likely to provide suboptimal patient care, reduce their workload and leave general practice9,11,18.

Scotland is the most rural nation in the UK, with 17.2% of its population living in either accessible rural, remote rural or very remote rural areas19. Many challenges are associated with rural general practice, which are well described in the literature20. These challenges have caused many rural areas in Scotland to have the steepest declines in full-time equivalent GP numbers8.

After a poll of GPs in 2017, a new General Medical Services (GMS) contract was introduced in Scotland in 201821. In rural areas, concerns were raised in terms of it negatively impacting primary care services, shared by both patients and doctors alike22. The contract confirmed the removal of the Quality and Outcomes Framework and introduced GP ‘clusters’: professional groupings of practices, which work together to drive improvement. The new contract also seeks to expand the multidisciplinary primary care team to help reduce GPs’ workload and it introduced a new funding formula, which aimed to better reflect practice workload and to ensure practice income stability21.

It is vital to understand what affects the job satisfaction of rural Scottish GPs and how this differs with non-rural GPs, to maximise the effectiveness of strategies to improve GP retention across the whole of Scotland. This article’s aim is to compare job satisfaction, job stressors, job attributes and intentions to reduce work participation between rural and non-rural Scottish GPs.

Methods

Design and setting

Data for both rural and non-rural GPs were taken from the Scottish School of Primary Care National GP survey, using validated measures of job satisfaction, stressors and attributes23.

Participants

The Scottish School of Primary Care survey was posted to all 4371 Scottish GPs in July 2018, with two follow-up reminder mailings with extra copies of the questionnaire sent in August and September 2018. The initial mailing in July included the option of completing the survey online, and two additional email reminders with the link to the online survey were sent in August. A total of 2465 GPs responded, giving a 56% response rate and a nationally representative sample of Scottish GPs23.

Each GP was asked to give their practice code or name. This then allowed each GP’s rurality to be defined from the practice location using the Scottish Government Urban Rural Classification on a scale of 1–824. Classes 1–5 represent settlements with populations of >3000; classes 6, 7 and 8 represent accessible rural areas, remote rural areas and very remote rural areas, respectively, all of which are areas with a population of <3000. This eight-fold classification can be simplified to six-fold, three-fold and two-fold classifications24. For this study, the two-fold classification system would be used, as a binary grouping is much less complicated in the analysis and subdividing classes 6–8 would have reduced the sample size for the rural groupings. As per the two-fold classification, GPs who worked in a practice in classes 6–8 were categorised as rural GPs, and GPs working in practices in classes 1–5 were categorised as non-rural GPs24.

Outcome variables

The Scottish School of Primary Care survey featured questions on four related domains of working lives: job satisfaction, job stressors, positive job attributes and negative job attributes, as well as questions on intentions to reduce work participation.

Domains of working lives: Job satisfaction was measured using questions about satisfaction with 10 different aspects of work, each of which were rated on a seven-point scale: 1 (‘extremely dissatisfied’) to 7 (‘extremely satisfied’)25. The answers were averaged to give a mean job satisfaction score in the range of 1–7.

Job stressors were measured after asking participants about pressure they experienced from 13 different job stressors. Pressure from each job stressor was rated on a five-point scale: 1 (‘no pressure’), 2 (‘slight pressure’), 3 (neutral’), 4 (‘considerable pressure’) and 5 (‘high pressure’). The answers were averaged to give a mean job stressor score in the range of 1–5.

Positive job attributes were measured by asking participants to rate how strongly they agreed with nine statements relating to desirable job aspects. Similarly, negative job attributes were measured by asking participants to rate how strongly they agreed with four statements relating to undesirable job aspects. Each job attribute was rated on a five-point scale, where 1 is ‘strongly disagree’, 2 is ‘disagree’, 3 is ‘neutral’, 4 is ‘agree’ and 5 is ‘strongly agree’. The answers were averaged to give mean positive and negative job attribute scores in the range of 1–5.

Intentions to reduce work participation: GPs’ intentions to reduce work participation were measured using four questions asking how likely they were in the next 5 years to reduce their work hours, leave medical work entirely, leave direct patient care or to continue medical work but outside the UK (to work abroad). All four questions are considered separate outcomes and were measured on a five-point scale where 1 is ‘none’, 2 is ‘slight’, 3 is ‘moderate’, 4 is ‘considerable’ and 5 is ‘high’.

The details of the domains of working lives and intention to reduce work participation are also stated by Hayes et al23 in their article, which compared data from the Scottish School of Primary Care survey to data from a similar survey of GPs in England.

Statistical analysis

Frequencies were run on all variables to check the data were clean and coded correctly. Differences in characteristics between rural and non-rural GPs were analysed using the χ2 test of association. This test was used because it tests whether there is a relationship between two variables, which each consist of two or more independent, categorical groups. Mean average scores for the domains of working lives were calculated and the independent samples t-tests were used to compare these between rural and non-rural GP groups because the mean average scores for the domains of working lives were continuous variables with normal distribution. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare scores for the intention to reduce work participation questions between rural and non-rural GP groups because the variables for intention to reduce work participation were ordinal with a non-parametric distribution.

Linear regression analysis was conducted on the mean domain of working lives scores and intention to reduce work participation scores to test if GP age, GP gender and any differences found between the two groups in terms of GP demographics had any effect. In this article, the criteria for a result (dependent variable) to be considered significant was p<0.05. The regression analysis included any demographic variables significant at the p<0.1 level, to ensure all potential independent predictors were controlled for26. The enter method was used for the linear regression because there were a small number of predictors, and it was not known which independent predictor would create the best prediction equation. An interaction variable between gender and rurality was added to the regression analysis to see if gender affected the association between rurality and working lives and intentions to reduce work participation. All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Science v25 (IBM; https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/spss-statistics/25.0.0).

Results

GP and practice characteristics

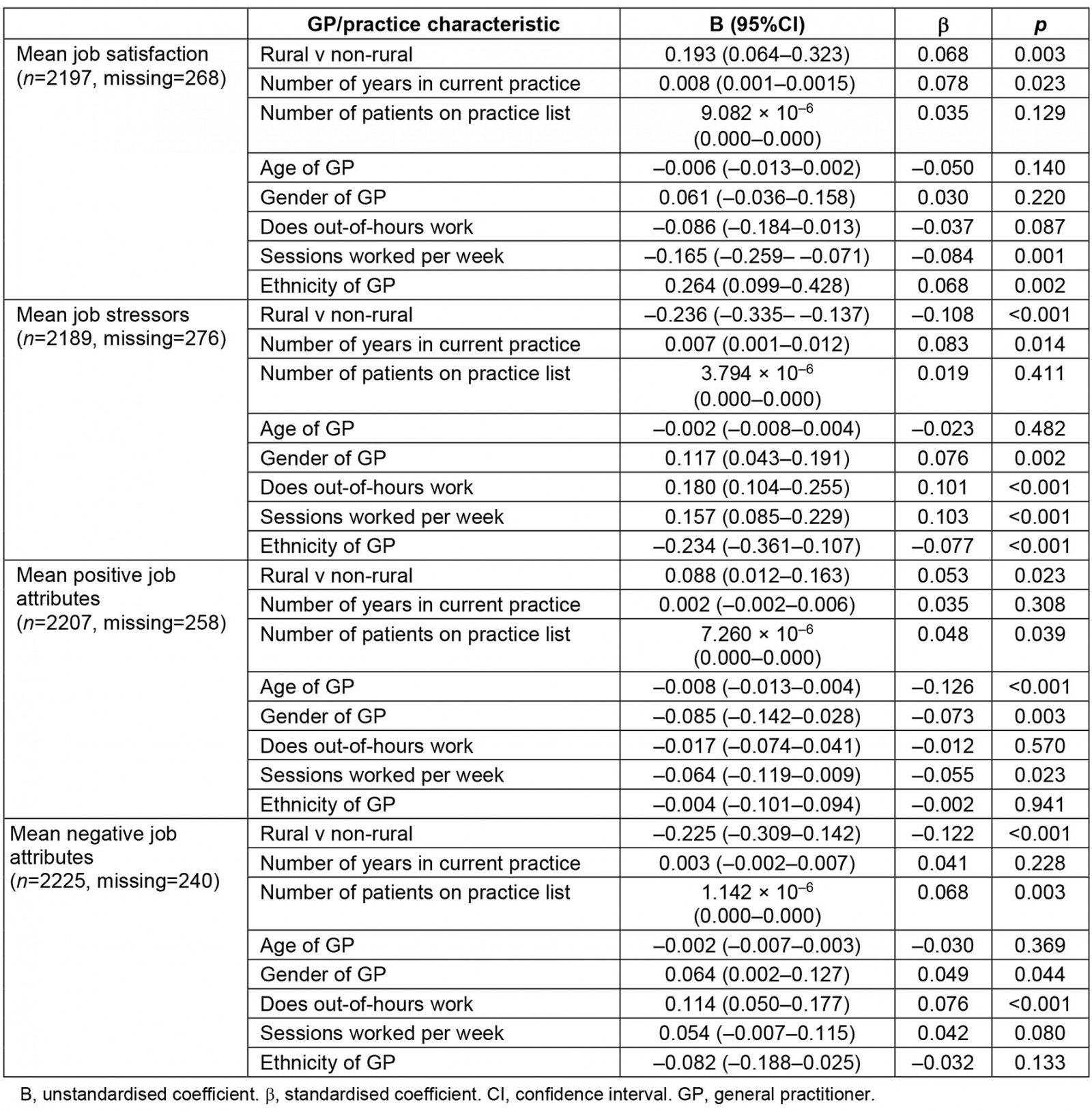

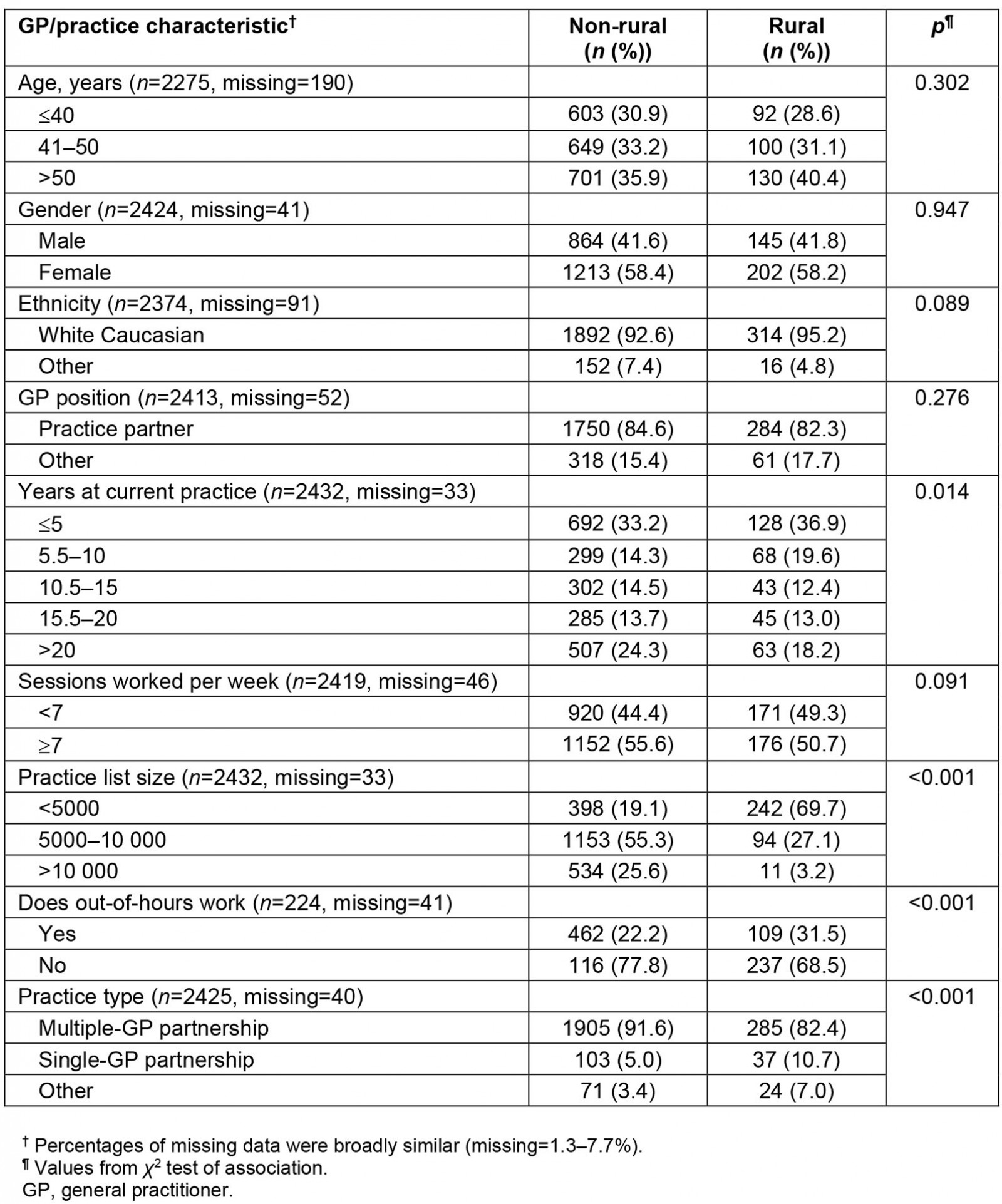

Out of the 2465 GPs who responded, 2432 (95%) gave information that allowed the classification of their practice. Out of these 2432 GPs, 2085 (85.7%) were classified as non-rural GPs and 347 (14.3%) were classified as rural GPs, according to the Scottish Government’s binary classification. Table 1 shows that, among GPs from rural and non-rural practices, there were no significant differences in the age, gender or proportion of GPs who are GP practice partners. Compared to non-rural GPs, rural GPs were significantly more likely to have been at their practice for fewer years, to work in smaller practices and to do out-of-hours work, and less likely to work in a multiple GP partnership (Table 1).

Table 1: Characteristics of rural GPs compared to non-rural GPs in Scotland (n=2465)

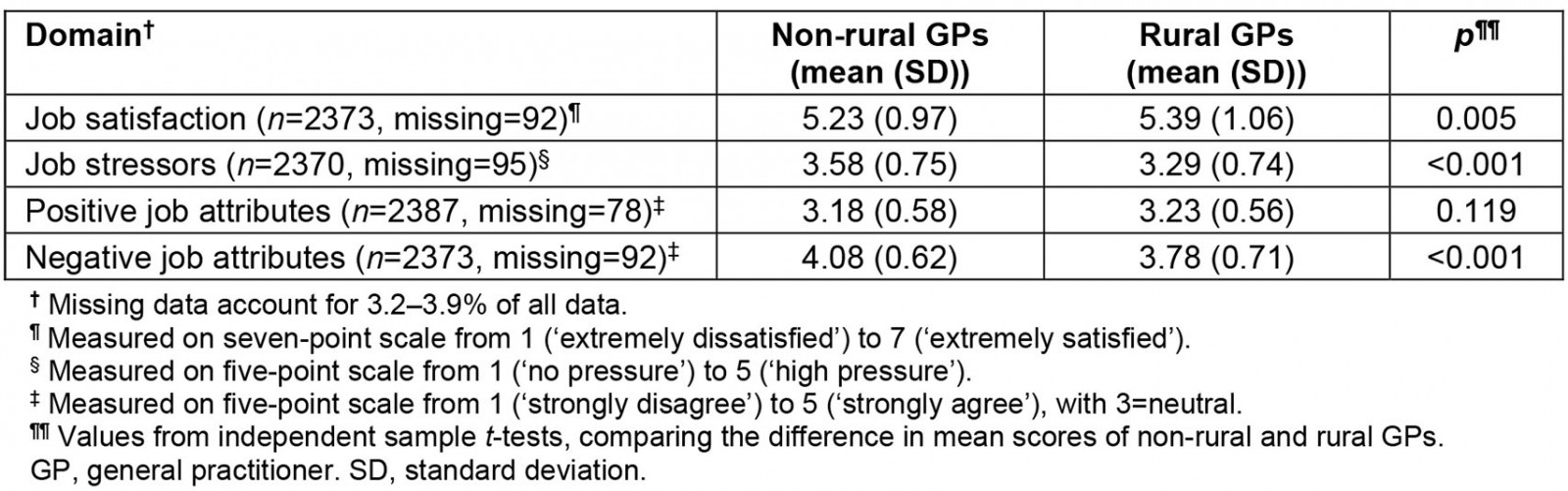

Comparison of working lives between rural and non-rural GPs

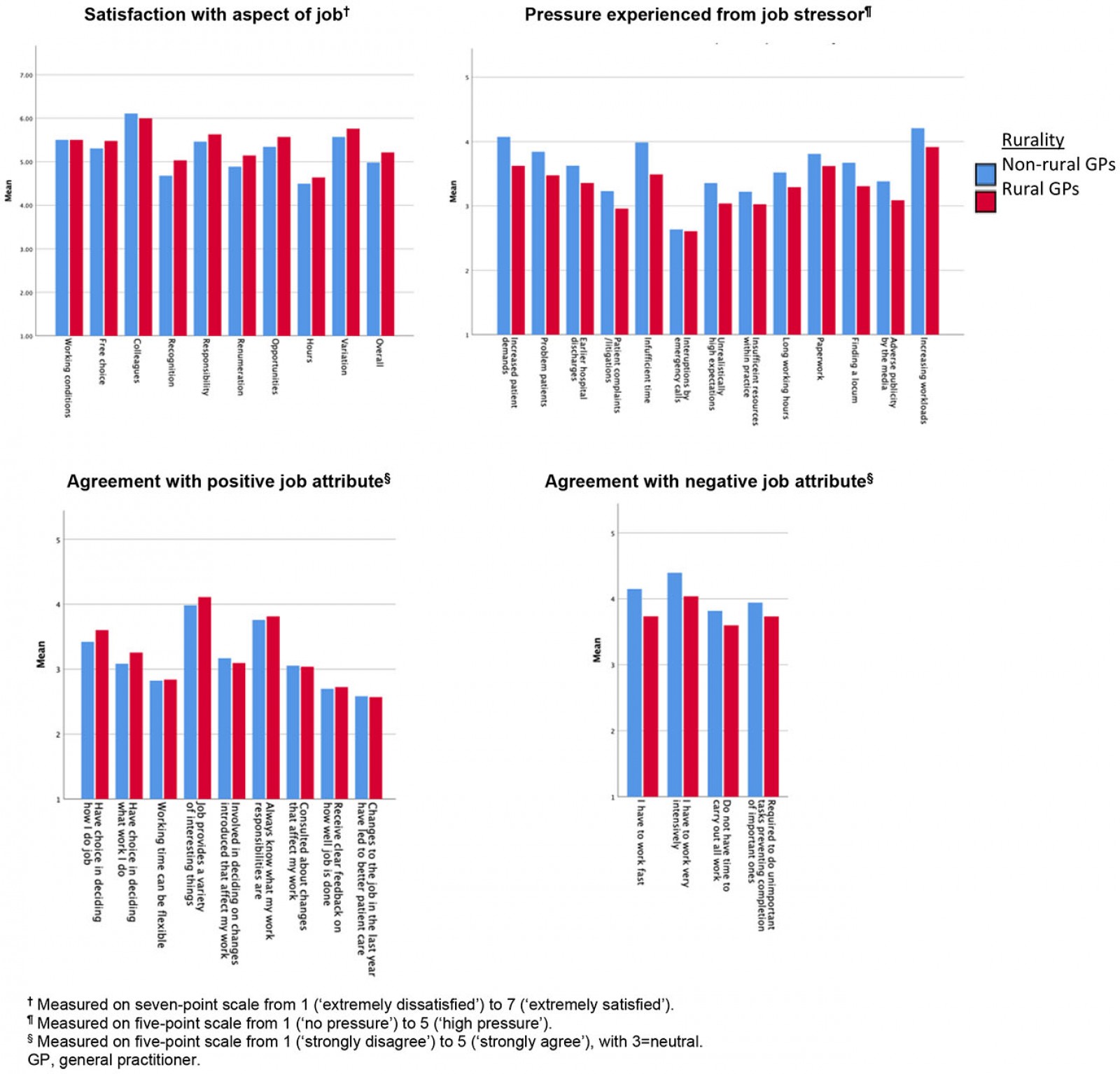

In unadjusted (univariate) analysis, rural GPs in Scotland reported significantly higher mean job satisfaction than non-rural GPs (Table 2); rural GPs were significantly more satisfied with the amount of free choice (p=0.008), recognition (p<0.001) and responsibility they get in their jobs (p=0.018) (Fig1). Rural GPs were also significantly more satisfied than non-rural GPs with remuneration (p=0.002), variation (p<0.001) and opportunities available in their jobs (p<0.001) (Fig1).

Rural GPs reported significantly lower mean job stressors than non-rural GPs (Table 2), with significantly less pressure from job stressors relating to patient demands (p<0.001), time (p<0.001), administrative tasks (p<0.001), earlier hospital discharges (p<0.001), unrealistically high expectations by others (p<0.001),and adverse publicity from the media (p<0.001) (Fig1).

Overall, both groups reported similar mean positive job attribute statements (Table 2). However, compared to non-rural GPs, rural GPs had significantly better scores relating to variety and autonomy: ‘My job provides me with a variety of interesting things’ (p=0.002), ‘I have a choice in deciding how I do my job’, (p=0.003) and ‘I have a choice in deciding what I do at work’ (p=0.006) (Fig1).

Rural GPs also reported lower mean negative job attributes than non-rural GPs (Table 2) and agreed significantly less with each of the four negative job attribute statements (p<0.001) (Fig1).

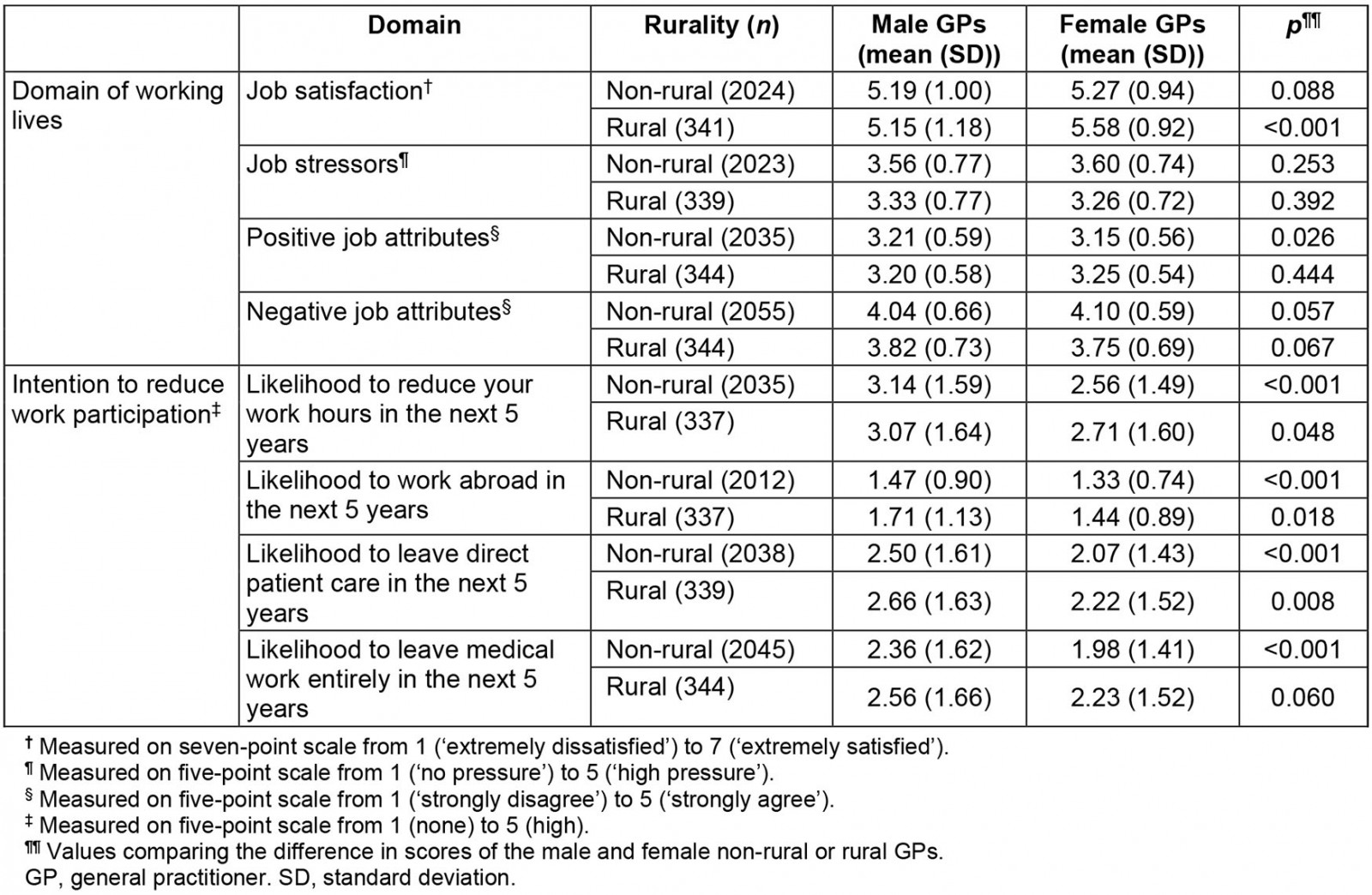

Univariate analysis also revealed that rural female GPs reported higher mean job satisfaction than male rural GPs (mean difference=0.43, p<0.001). Rural male GPs had very similar mean job satisfaction scores to non-rural male GPs (means=5.15, 5.19) (Table 4).

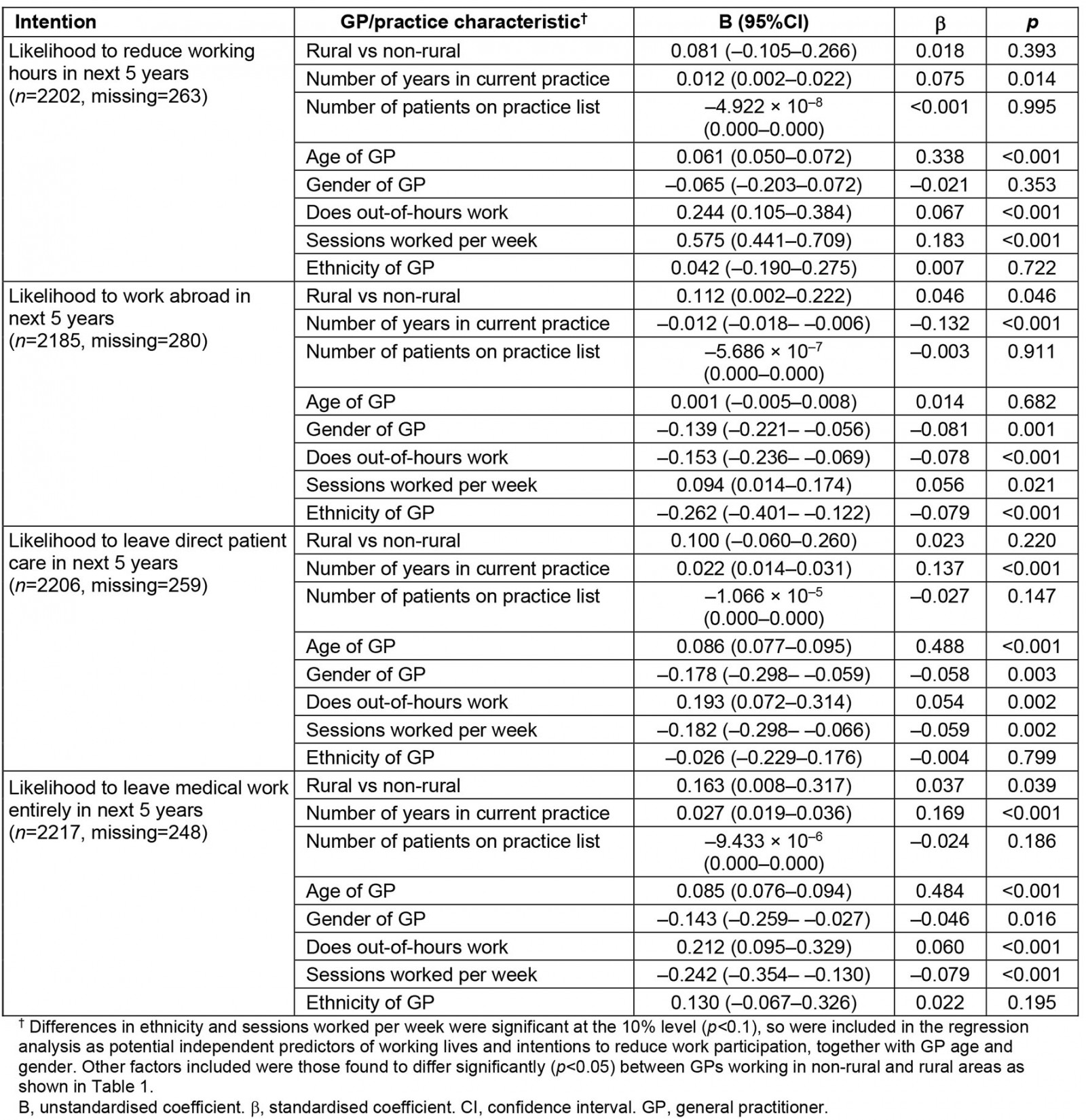

These apparent differences between the two groups of GPs found in the univariate analyses were explored in adjusted (multivariate) analysis, to control for potentially confounding factors between GPs in rural and non-rural areas. Adjusted analysis revealed that compared with GPs in non-rural settings, GPs in rural areas had higher mean job satisfaction (p=0.003), (Supplementary table 1). An interaction variable between gender and rurality was added into the regression model, which showed a significant interaction between GP gender and rurality in mean job satisfaction (β=0.093, p=0.008). No significant interactions were found between GP gender and rurality for the other three domains of working lives (job stressors, p=0.113; positive job attributes, p=0.090) and negative job attributes, p=0.053).

Table 2: Domains of working lives mean scores for non-rural GPs v rural GPs in Scotland (n=2465)

Figure 1: Scottish GPs’ mean scores for individual questions on the domains of working lives in rural and non-rural settings.

Figure 1: Scottish GPs’ mean scores for individual questions on the domains of working lives in rural and non-rural settings.

Intentions to reduce work participation

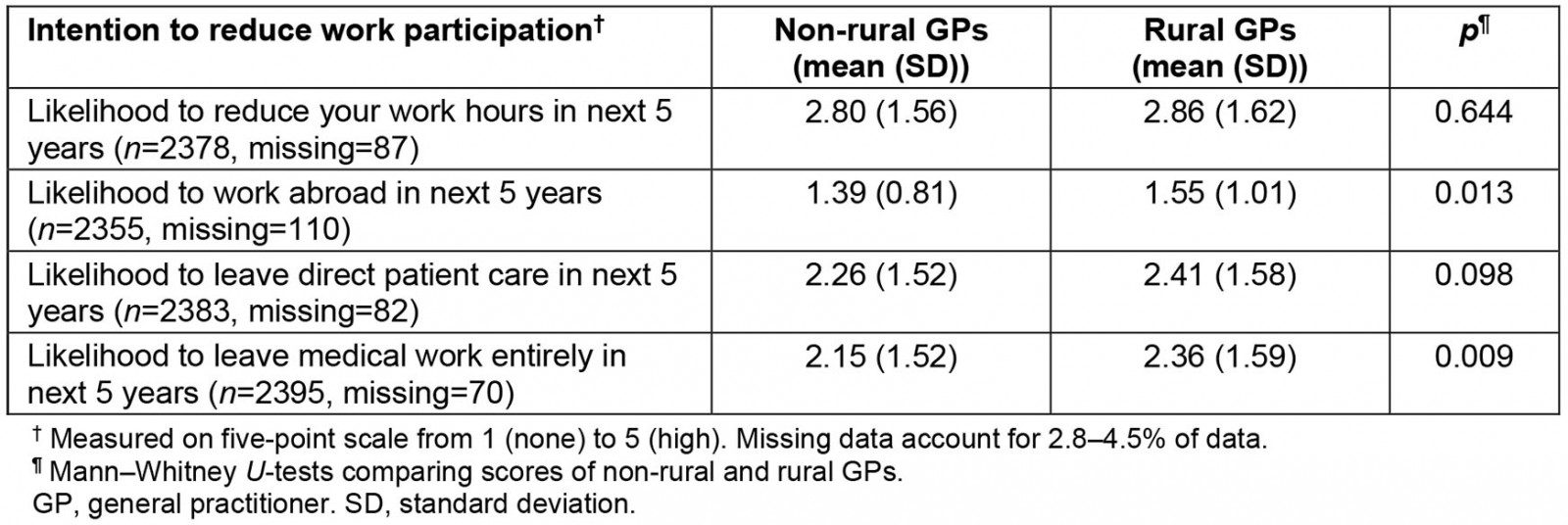

In unadjusted (univariate) analysis, rural GPs were more likely to anticipate that they would work abroad or leave medical work entirely in the next 5 years than non-rural GPs. There were no significant differences between rural and non-rural GPs for intentions to reduce their work hours or leave direct patient care in the next 5 years (Table 3). Univariate analysis also found male GPs were more likely than female GPs to reduce their hours, work abroad and leave direct patient care in the next 5 years in both rural groups (p=0.048, 0.018, 0.008, respectively) and non-rural groups (p<0.001) (Table 4).

After controlling for other potential independent predictors in adjusted (multivariate) analysis, working in a rural area remained positively associated with likelihood to work abroad and to leave medical work entirely in the next 5 years (Supplementary table 2).

However, no significant interaction was found between GP gender and rurality for intentions to reduce work participation by reducing work hours, working abroad, leaving direct patient care or leaving medical work entirely (p=0.552, 0.154, 0.742, 0.927, respectively).

Table 3: Intentions to reduce work participation of non-rural GPs v rural GPs in Scotland

Table 4: Domains of working lives and intention to reduce work participation mean scores of male and female GPs working in non-rural and rural areas of Scotland

Discussion

In a large and nationally representative survey of GPs’ working lives in Scotland the authors found important differences between GPs working in rural and non-rural settings. GPs in rural areas reported significantly higher job satisfaction, lower job stressors and lower negative job attributes compared with GPs in non-rural settings. However, this overall higher job satisfaction was due to rural female GPs’ high job satisfaction scores. Rural GPs were, however, more likely to intend to work abroad and leave medical work entirely within 5 years than non-rural GPs, and this was not related to gender.

The reasons behind this surprising finding that higher job satisfaction was linked to a higher intention to move or quit in rural areas can only be surmised. GPs in rural areas were significantly more satisfied with their remuneration than those in non-rural areas, and it is possible that rural GPs have higher earnings and/or the cost of living is lower than in more non-rural settings, and thus they can financially afford to retire earlier. According to various media reports, many rural GPs also had concerns over the new Scottish General Medical Services (GMS) contract when it was first introduced which perhaps made them more likely to consider early retirement. Other possible reasons may be unrelated to work per se, such as family life and geographical isolation.

Recent research has found that patients in rural areas of Scotland are more satisfied with their GP practice than patients in non-rural areas, and this trend has stayed consistent for over a decade27. Patients in rural areas were more satisfied with their practice in terms of continuity of care and aspects of patient-centred care, particularly the amount of time they were given when seeing their GP27. This higher patient satisfaction in rural areas may also contribute to rural GPs’ increased job satisfaction. Alternatively it might suggest that rural patients are generally less demanding, which is supported by the present study’s finding that, compared to other GPs, rural GPs experience significantly less pressure from increased demands from patients.

Some 20 years ago, Simoens et al16 analysed survey data from 802 GPs in Scotland using the same measures of job satisfaction and similar measures of job stressors and intentions to quit as the present study used. GPs appeared to be more satisfied across the measures of job satisfaction in 2018 than they were in 2001. However, research suggests GP job satisfaction increases after the introduction of a new contract28, and the current survey was conducted soon after the introduction of the new GMS contract in April 2018. Simoens et al found no difference in job satisfaction or stressors between rural and urban GPs16; however, comparisons are limited due to the differences in sample size and the classification of rurality used in the two studies.

Research across many western countries has found GPs who work in rural areas are often more satisfied than their urban counterparts, and some research has attributed rural GPs’ increased job satisfaction to them carrying out a larger range of activities than urban GPs12,15,29,30. The present study’s findings corroborate these previous findings. Research by Ulmer and Harris30 found that rural GPs in Australia were more satisfied than urban GPs using the same measures of job satisfaction as the present study. Research in Australia by Gardiner et al31 found 52.7% of rural GPs surveyed had seriously considered leaving rural general practice in the previous 2 years. In comparison, only 26.7% of rural GPs in the Scottish School of Primary Care survey reported the likelihood of them leaving medical work entirely in the next 5 years as ‘considerable’ or ‘high’, suggesting the rural GP retention rate may be higher in Scotland than in Australia.

The strengths of the present study include the relatively high survey response rate of 56% of all GPs in Scotland, which is higher than most previous studies. Given the respondents were nationally representative in terms of age, gender and practice deprivation, the findings may be generalisable to the Scottish GP workforce. Another strength is the use of validated measures for the domains of working lives. The main weakness of this article is that the cross-sectional design of the survey means causal inferences should only be drawn with great caution. A second potential weakness is that data relating to some factors, such as GPs’ mental health, remuneration and relationships with patients, were not gathered, and these may have influenced the findings if they had been included in the survey, especially as these have been found in previous work to affect GP job satisfaction12,13,32. Finally, statistical significance does not necessarily equate with meaningful differences, and many of the differences in mean scores were of a rather small magnitude. However, job stressors and negative job attributes showed differences of moderate magnitude (a third to almost a half of standard deviation), and thus are likely to be meaningful in practice.

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly changed the way GPs and patients interact together, with many more phone, video and email consultations now being held33. The data used in this article were collected before the COVID-19 pandemic began, so future research is needed to explore how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the working lives of Scottish GPs, and whether it has affected rural and non-rural GPs differently.

Conclusion

This study identified significant differences in working lives between rural and non-rural GPs in Scotland. After controlling for these differences, rural GPs were more satisfied, experienced less pressure from job stressors and were happier with most of the aspects of their job compared to non-rural GPs; yet rural GPs were more likely to intend to leave medical work entirely in the next 5 years. Further analysis showed rural GPs’ increased job satisfaction can be attributed to female rural GPs’ increased job satisfaction. Although some of these differences are small, they may signal serious implications for the future care of patients in rural areas. These findings also corroborate research conducted across the world finding that rural GPs are more satisfied despite the challenges of rural general practice. Future research should explore why rural GPs are more likely to leave despite higher job satisfaction and how the new GMS contract and COVID-19 has affected the working lives of GPs in Scotland.

References

Supplementary material is available on the live site https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/7270/#supplementary

You might also be interested in:

2007 - Drivers of professional mobility in the Northern Territory: dental professionals