Dear Editor

The COVID pandemic has affected provision of outpatient services due to face-to-face clinic cancellation. Our local paediatric diabetes service sought innovative solutions to service replacement, initiating telephone clinics and then drive-through clinics (families travelling to the clinic, but remaining in the car, with blood obtained for HbA1c from the patient’s finger projecting through an open car window). Concerns remained that COVID lockdowns would adversely affect clinic attendance, despite changes to clinic structures to mitigate this. The clinic cares for a rural population, covering the south-west quarter of Wales, in the United Kingdom.

Non-attendance at a clinic potentially leads to suboptimal outcomes and poor utilisation of resources. Higher HbA1c has been associated with higher missed clinic rates1. In our context, it is important to know the implications of clinic changes due to the pandemic on clinic attendance rates and therefore the overall care of diabetic children.

A retrospective review of electronic data for 184 paediatric diabetes patients in a rural setting in south-west Wales was undertaken. Comparisons between numbers recorded as attending the clinic, ‘did not attend’ (ie non-attendance with no explanation) or ‘could not attend’ (ie non-attendance with explanation) were made, for two periods of 6 months (April – September 2019 and 2020), covering pre-COVID face-to-face clinics and COVID-lockdown virtual clinics. Rates of clinic attendances for individual patients were tracked through. Patients’ glycaemic control (HbA1c) during the specified time intervals was also recorded.

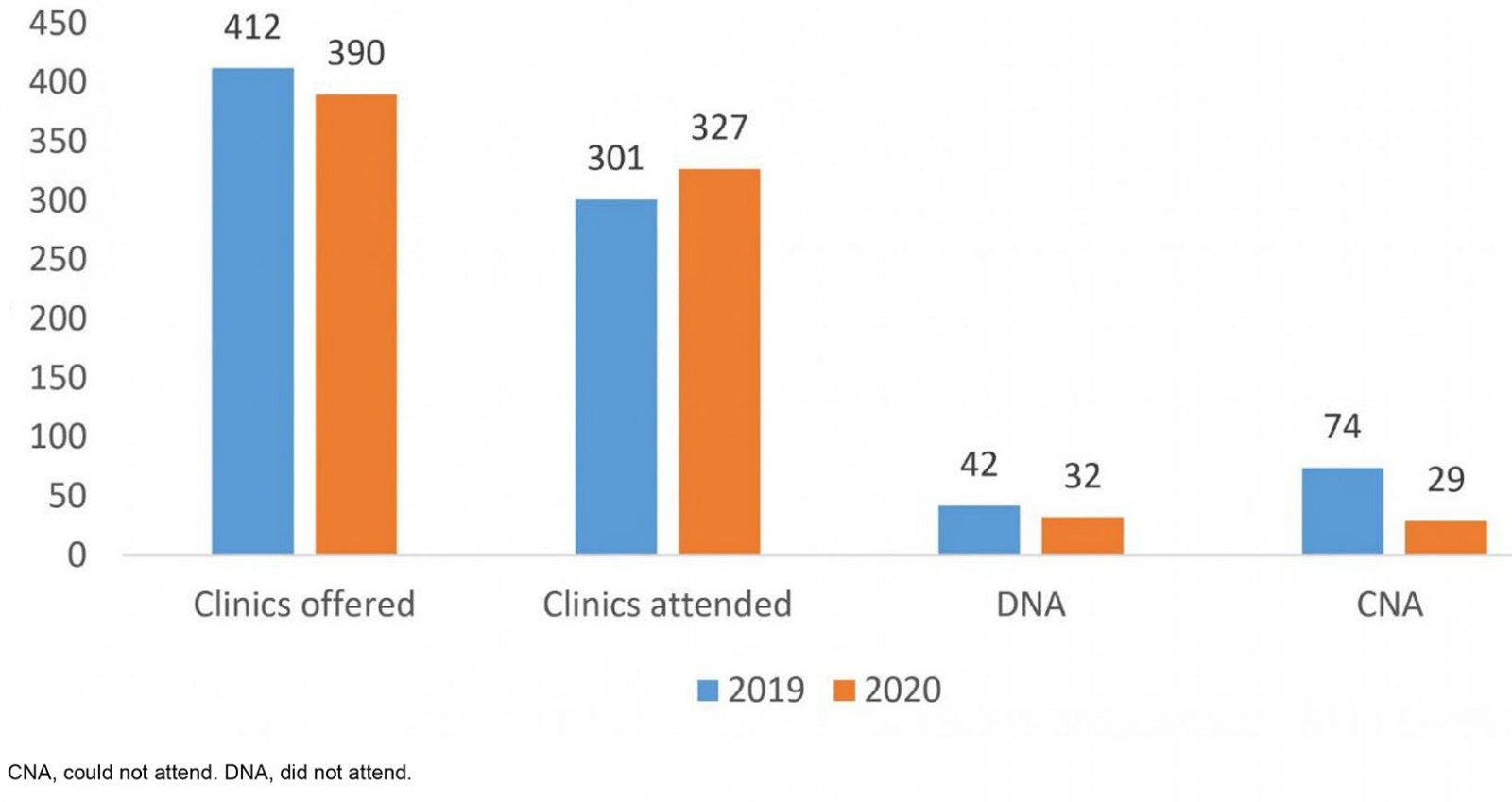

In 2019, a total of 412 individual clinic slots were offered, of which 301 (73.05%) were attended. In 2020, a total of 390 virtual clinic appointments were offered (151 by telephone, 239 drive-through), of which 327 (83.84%) were attended. Did-not-attend rates remained stable (10.19% in pre-lockdown v 8.20% during lockdown), while could-not-attend rates reduced (from 17.96% during pre-lockdown to 7.34% in COVID lockdown) (Fig1). Mostly the same children did not attend in both time periods. Mean HbA1c was unaffected in both the time periods (59.26 mmol/mol v 59.75 mmol/mol). The national average mean of unadjusted HbA1c during 2019–20 was 65 mmol/mol2.

We found that the overall attendance for virtual clinics seemed to improve during the pandemic, due to a reduction in could-not-attend rates. Offering virtual appointments in a rural healthcare setting, where travel is already potentially difficult, improves access to ongoing clinic care.

A similar outcome occurred in another study where diabetic patients were followed up in a tertiary paediatrics centre through telemedicine involving audio, and audio with video remote clinics3. Offering virtual clinics may help families when they are unable to attend in person; families may have been more likely to have been at home and able to answer telephones and attend the drive-through clinics. Mostly the same children who did not attend clinics pre-COVID did not attend during the pandemic – suggesting clinic attendance for them needs further research to address reduced opportunity to access services. Either innovative working practices improved clinic attendance, or the pandemic facilitated more opportunities for families to attend the clinic, as they were more likely to have been available and at home. This research will inform future clinic planning for the next pandemic.

Dr Thomas Almeida (Foundation year 2 trainee, Paediatrics Department, Glangwili General Hospital), contributed to data collection. We thank him for his valuable contribution to our study.

Figure 1: Clinic attendance numbers pre-COVID and during COVID lockdown for paediatric diabetes patients in a rural clinic in south-west Wales (n=184).

Figure 1: Clinic attendance numbers pre-COVID and during COVID lockdown for paediatric diabetes patients in a rural clinic in south-west Wales (n=184).

Dr Divya Neha Pharasi, Dr Swe Lynn & Dr Simon Fountain-Polley, Department of Paediatrics, Glangwili General Hospital, Hywel Dda Health Board, Dogwili Rd, Carmarthen, West Wales

References

You might also be interested in:

2013 - Retraction

2006 - Medical students' assessments of skill development in rural primary care clinics