Introduction

The inequitable distribution of health workers within various countries has led to an imbalance between the supply and demand of health services in many regions1,2. Rural and remote areas have historically struggled with shortages of health workers3. Even in high-income countries, people in rural and remote areas experience a range of health problems. And due to socioeconomic factors, increased health risk factors, and poverty, their health status often differs significantly from that of metropolitan residents4,5. Rural and remote residents, therefore, have substantial healthcare needs. Health workers in rural and remote areas undoubtedly require a specific set of skills. For example, healthcare providers are called upon to treat a variety of diseases, provide multiple health services, and perform a wide variety of procedures6-10. It can be seen that health workers in rural and remote areas shoulder heavy responsibilities as gatekeepers of the health of rural residents11.

Previous studies have shown that health workers in rural and remote areas have limited knowledge and service capacity to meet the medical service needs of residents. For instance, studies from China showed that most primary health workers have low levels of education and are not adequately equipped to provide high-quality services12,13. Moreover, studies in rural New Mexico reported many barriers for health workers in accessing valuable information resources14,15. Many studies have confirmed that existing primary health workers perform poorly in both preventive and clinical services, such as chronic disease management diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis, and antibiotic prescribing16-18.

An effective measure to enhance the health service capacity of health workers is to provide continuing education programs. Continuing medical education is part of the lifelong learning process that all physicians undertake from career to retirement. All physicians need to undertake lifelong learning to ‘maintain, develop or increase the knowledge, skills, professional performance and relationships used to provide services to patients, the public or the profession’, while being able to update their medical knowledge19. Through continuous learning, rural and remote health workers are constantly updating themselves to meet the needs of patients for health services, as well as their professional development20. In a growing number of journal articles and professional reports, academics and policymakers are seeing the role of continuing medical education in improving health outcomes, particularly physician performance and patient health status21-23. Since the mid-1960s, many organizations, including the World Health Organization, governmental and non-governmental organizations, have conducted continuing education programs for rural health workers24. These programs are currently widely used in many countries and aim to improve the capacity of health workers in rural and remote areas to provide basic national health services to reduce health inequalities across regions, ethnicities and groups25-27.

Several studies have investigated the effectiveness of continuing education programs for health workers in rural and remote areas. However, a systematic review or meta-analysis on this topic is lacking. The objective of the present study was to evaluate the effectiveness of continuing education for health workers in rural and remote areas by conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

Search strategy

Our findings were reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline28. Four electronic databases for studies published in English (PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and EMBASE) and four published in Mandarin (Chinese Biomedical database, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang Data, and VIP) were comprehensively searched from inception to 28 November 2021. We did keyword and MeSH searches as follows: ‘rural’ AND (‘health worker’ OR ‘physician’ OR ‘doctor’) AND (‘education’ OR ‘training’) AND ‘control’, and the specific search strategy is shown in Appendix I. We checked reference lists of relevant reviews for additional studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Types of studies: It was anticipated that there would be very few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving continuing education for health workers in rural and remote areas, and a broader range of study designs was included based on the recommendations of the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC) group. RCTs, cluster-randomized controlled trials (cRCTs), non-randomized controlled trials (nRCTs), controlled before and after (CBA) studies, interrupted time series studies, and repeated measure studies were assessed. Study protocols and incomplete studies were excluded.

Types of participants: The participants we included were all categories of health workers, both professionals and lay health workers, who provide healthcare services in rural and remote areas. Health professionals included physicians, nurses, midwives, nursing assistants, pharmacists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dentists, dental assistants, laboratory technicians, dispensers, medical assistants or clinical officers, and radiographers29. We defined a lay health worker as any health worker who performs functions related to healthcare delivery, is trained in some way to provide these functions, but has received no formal professional or paraprofessional certificate or tertiary education degree30.

Types of interventions: We included any form of study involving continuing education programs that was defined explicitly; was conducted as a single intervention; and aimed to produce changes in health workers’ knowledge, performance or patient outcomes. We anticipated that the control group would be no intervention.

Types of outcome measures: We included studies that reported:

- knowledge (the degree to which health workers have mastered the knowledge involved in continuing education activity)

- performance (the degree to which health workers do what the continuing education activity intended them to be able to do in their practices)

- patient health (the degree to which the health status of patients improves as a result of changes in the practice behavior of health workers)

- community health (the degree to which the health status of a community of patients changes as a result of changes in the practice behavior of health workers).

Study selection and data extraction

Studies were selected independently by two reviewers, and disagreements were resolved in consultation with a third reviewer. After eliminating duplicates, titles and abstracts were read to exclude irrelevant studies, after which the full text was assessed for final study inclusion.

Two reviewers extracted data independently using a standardized study form, which included study information (ie year of publication and first author’s name, geographic location, setting, and study design), characteristics of participants (ie population type, sample size), intervention characteristics (ie education form, education content, intervention time, comparison group, and length of follow-up), and outcomes. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion. If the data were not available, we tried to contact the study authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias was assessed using tools provided by EPOC31,32 and was done independently by the two review authors. Each item was classified as low, high, or unclear risk of bias, and the results were displayed by summary plots. A third review author was consulted, and consensus was reached when there was disagreement on the assessment.

Data synthesis and analysis

Odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to indicate the merger effect because the included studies reported dichotomous data, and p<0.05 was statistically significant. Heterogeneity between the results was assessed by the c2 test and I2 test, and if there was significant heterogeneity (p<0.05 or I2>50%), a random-effects model was used; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used. Review Manager (RevMan) v5.4 (Cochrane; https://revman.cochrane.org/info) was used for statistical calculations of all data. In addition, because of the lack of consistency in measurement results, studies that could not be meta-analyzed were reviewed by using a narrative synthesis. The methodology was as follows: effects were summarized by training content, with expected outcomes categorized into four main domains: knowledge, behavior, patient health, and community health. Findings were classified as ‘positive’ (+) if there were statistically significant positive changes in all measures. Where studies did not include inferential statistics, results were classified as ‘positive’ (+) if they were reported as positive by the study authors. If some but not all measurements reported positive results, the study results were classified as ‘partially positive’ (+/0). Findings were categorized as ‘no effect’ (0) if there were no statistically significant changes. Findings were categorized as ‘negative effect’ (–) if there was a statistically significant negative change.

Ethics approval

This research was done without patient or public involvement, so ethics approval was not required.

Results

Study selection

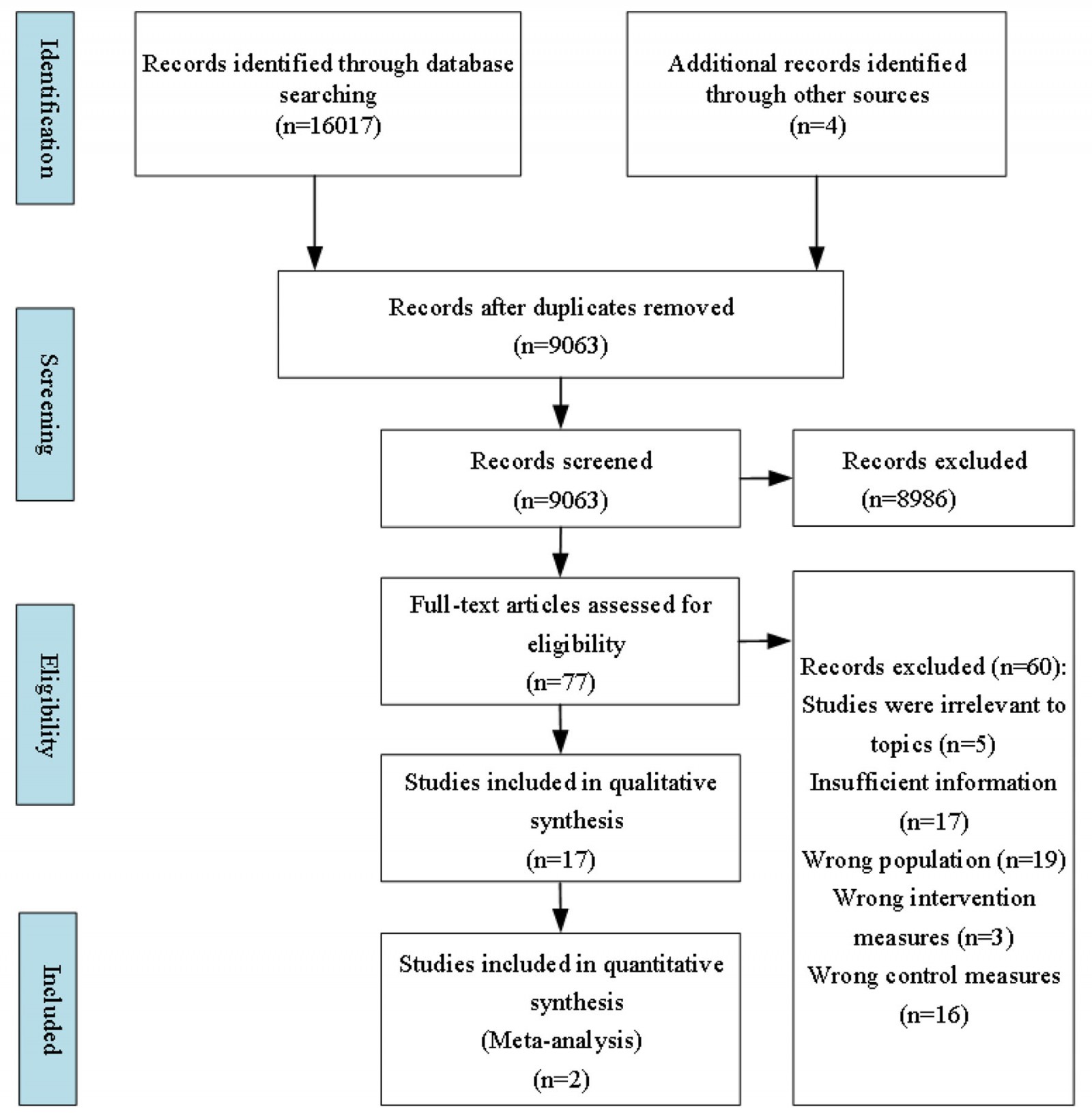

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flowchart. In the search strategy, a total of 16 021 citations were found, of which 9063 remained after removing duplicates. Of these, 8986 studies were excluded by browsing titles and abstracts. After excluding irrelevant studies, the 77 remaining full-text studies were assessed for eligibility. Sixty studies were excluded because of studies being irrelevant to topics (n=5), insufficient information (n=17), wrong population (n=19), non-single continuing education programs (n=3), and control group not ‘no intervention’ (n=16).

Figure 1: A flow diagram of the literature screening process and results.

Figure 1: A flow diagram of the literature screening process and results.

Study characteristics

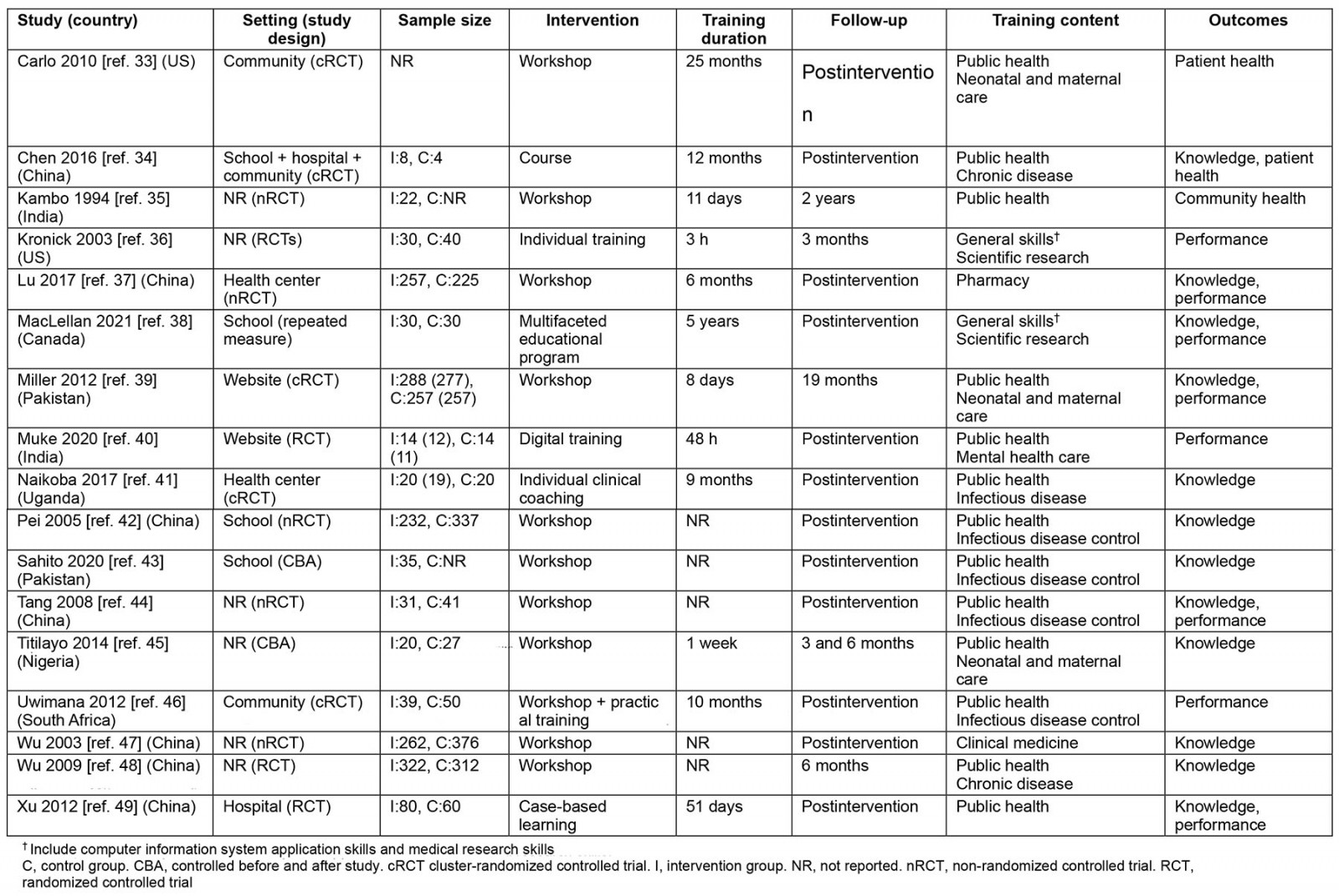

Table 1 summarizes the general characteristics of the included studies33-49. Three of the 17 studies were distributed in high-income countries, eight from upper-middle-income countries, five from lower-middle-income countries, and one from low-income countries (according to World Bank country classification)50, all of which were published between 1994 and 2021. Study designs included RCTs (n=4), cRCTs (n=5), nRCTs (n=5), CBA (n=2), and repeated measure studies (n=1). The studies were mainly conducted in schools (n=3), health centers (n=2), communities (n=2), and websites (n=2), and six studies did not report training sites. Primary components of interventions included workshop, course, case-based learning, multifaceted educational programs, individual training, and digital training. The training covered four categories: clinical medicine, public health (eg neonatal and maternal care, chronic disease, infectious disease, mental health care), general skills (which include computer information system application skills, and medical research skills), and pharmacy. The overall length of the intervention ranged from 3 hours to 5 years. Twelve studies assessed outcomes immediately after the end of the intervention. Additional follow-up analyses were conducted in five studies, ranging from 3 months to 2 years.

Table 1: Characteristics of the 17 experimental studies included in the review33-49; the control for all studies was ‘no intervention’

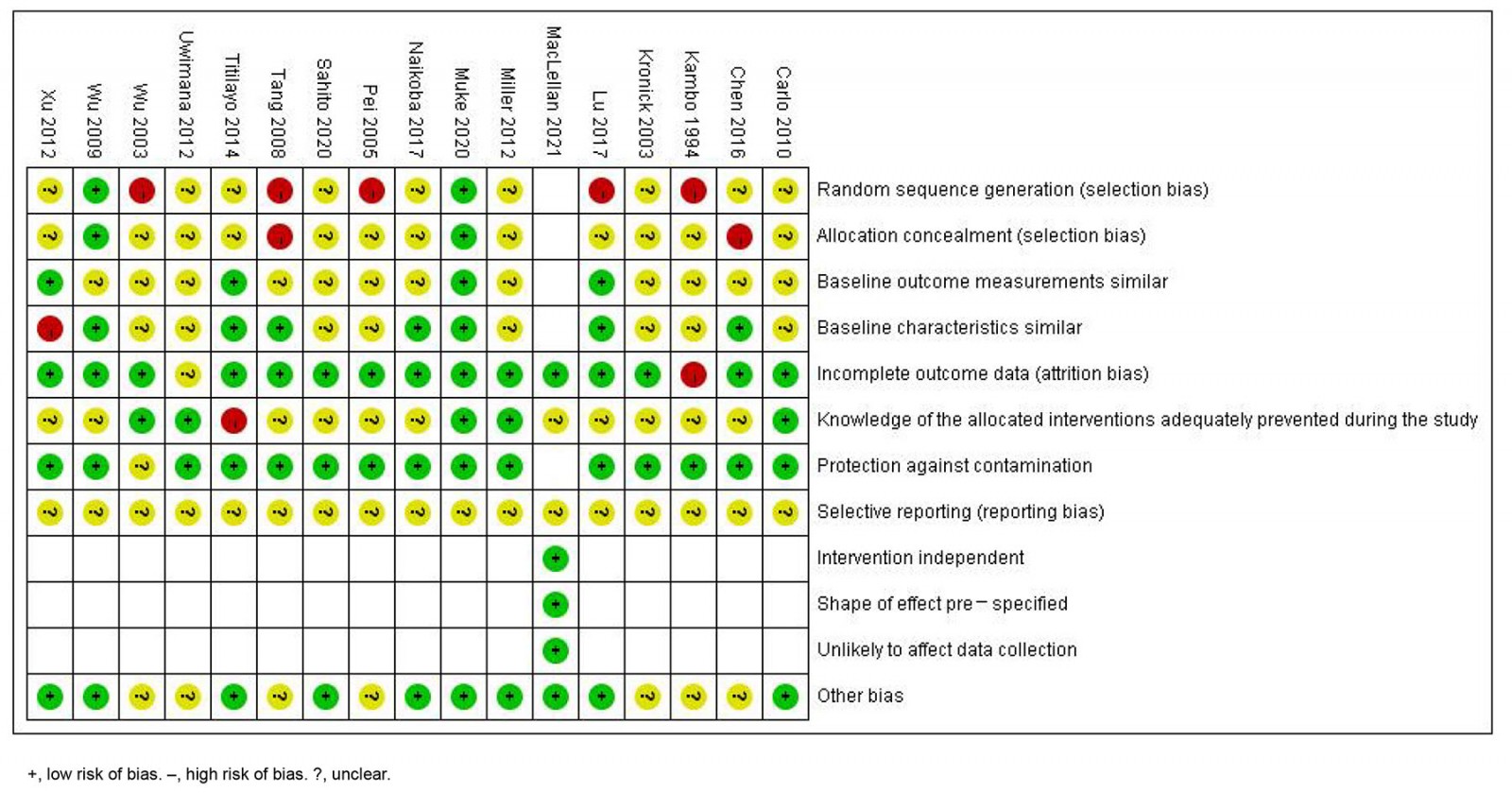

Risk of bias

Eight studies were assessed as having a high risk of bias, nine as having an unclear risk of bias. The most common sources of high risk of bias were random sequence generation (five studies) and allocation concealment (two studies). One trial had information suggesting that outcome measures were not blinded. Seventeen studies had no available protocol and insufficient evidence to comment on any selective reporting bias. Seven studies had other bias entries rated as unclear because they did not report funding information. A summary of the risk of bias is provided (Fig2).

Figure 2: Summary of review authors’ judements about each risk of bias item.

Figure 2: Summary of review authors’ judements about each risk of bias item.

Meta-analysis

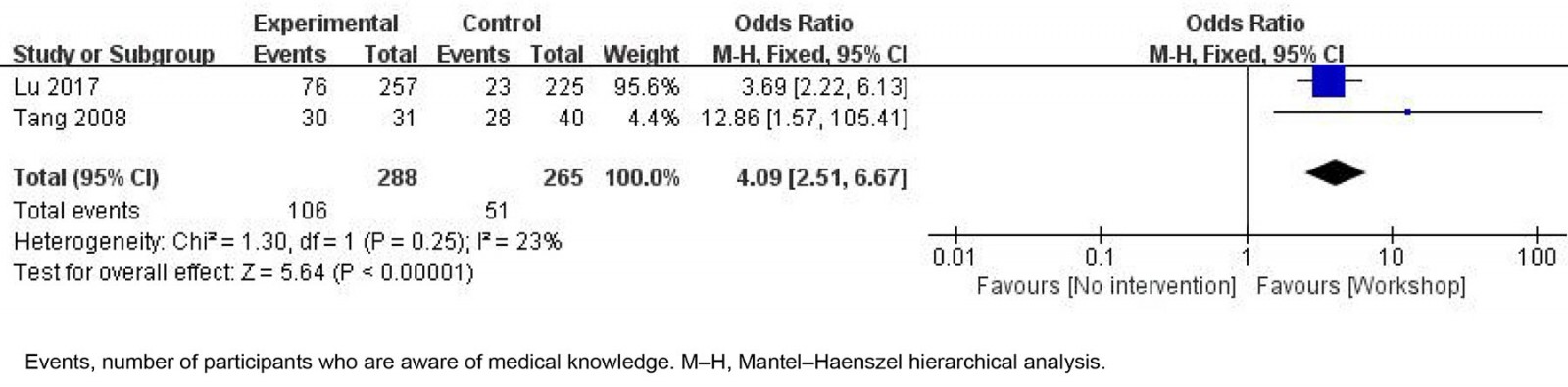

Two nRCTs37,44, both from China, and including 553 health workers, evaluated the effectiveness of continuing education programs on health workers’ knowledge awareness rate. Compared with no intervention, the meta-analysis results (Fig3) demonstrated that continuing education programs have significantly improved the medical knowledge awareness rate of health workers in rural and remote areas (OR=4.09, 95%CI 2.51–6.67, p<0.05).

Figure 3: Effectiveness of continuing education on awareness rate in rural and remote health workers.

Figure 3: Effectiveness of continuing education on awareness rate in rural and remote health workers.

Qualitative analysis

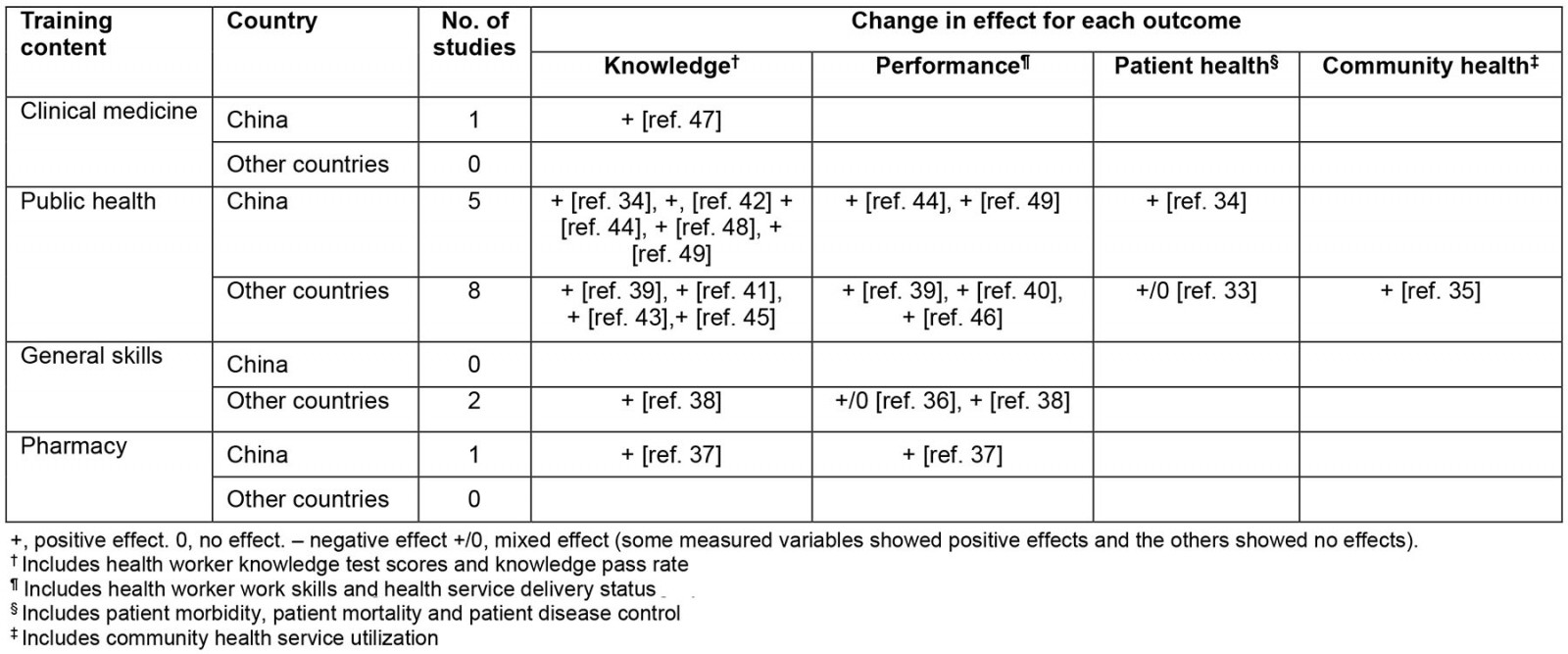

Effectiveness based on different training content: A qualitative analysis of the included studies was carried out using a narrative synthesis, and the results were summarized by educational content and type of outcomes measured. A summary of these findings is presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Summary of the educational content and corresponding outcomes for the studies

Knowledge: Twelve studies34,37-39,41-45,47-49 measured the knowledge of health workers in rural and remote areas, and all showed that continuing education programs improved the knowledge level of rural and remote health workers compared with no intervention.

In terms of clinical knowledge, only one study47 from China showed that continuing education programs improved rural and remote health workers’ knowledge of the diagnosis and treatment of common diseases compared with no intervention (p<0.01).

In terms of public health knowledge, five studies from China34,42,44,48,49 and four studies from Pakistan39,43, Uganda41 and Nigeria45 reported on the public health knowledge of rural and remote health workers. Compared with no intervention, all nine studies included34,39,41-45,48,49 reported positive and significant differences in the outcomes of continuing education programs. Compared to the control group, continuing education programs significantly improved rural and remote health workers’ knowledge of chronic disease management (all p<0.05)34,48, neonatal and maternal care (all p<0.05)39,45, basic public health services (all p<0.05)49, and infectious disease control (all p<0.05)41-44.

In terms of general skills, a study from Canada showed improvement in scientific research methods and writing skills (p<0.0005)38.

In terms of pharmacy knowledge, a study from China showed improvement in antithrombotic drug knowledge among health workers (p<0.001)37.

Performance: Eight studies36-40,44,46,49 measured the behavior of rural and remote health workers. Seven studies37-40,44,46,49 showed that continuing education programs improved rural and remote health worker performance compared with no intervention, and only one36 showed mixed effects of continuing education programs on rural and remote health worker performance.

In public health, two studies from China44,49 and three studies from Pakistan39, India40 and South Africa46 reported on the performance of health workers in rural and remote areas. Existing studies39,40,44,46,49 have shown positive changes in the performance of rural and remote health workers, compared to a control group. Continuing education programs significantly improved the skills of rural and remote health workers in safe vaccination practices (p<0.05)44 and basic public health services practices (p<0.05)49, the skills of rural and remote midwives in neonatal and maternal care (p<0.01)39, and the capacity of health workers in rural and remote areas to assess depression (p<0.01)40. Also, one study46 showed that continuing education programs increased the rate of screening for tuberculosis and sexually transmitted infections symptoms and tracing of tuberculosis contacts among rural and remote health workers (all p<0.001).

In terms of general skills, two studies36,38 from the US reported changes in health workers’ performance. One study36 showed mixed effects; specifically, the intervention group significantly increased the frequency of accessing the internet to solve patient-related problems, the comfort level of accessing online databases, and the frequency of accessing online databases compared with the control group (all p<0.05). However, the intervention group did not change significantly compared with the control group in terms of the frequency of using email to solve patient-related problems (p=0.924) or the comfort level of accessing email (p=0.237). The other study38 showed that continuing education programs can improve the scientific research skills of rural and remote health workers (p<0.0005).

In terms of pharmacy, only one study37 from China showed that continuing education programs improved health workers’ understanding of the correct use of antithrombotic drugs (p<0.001).

Patient health: Two studies33,34 reported on the health status of patients in public health. One study34 from China showed that continuing education programs improved blood pressure control and prevalence of hypertension in patients with hypertension compared with no intervention (p<0.05). A study33 from the US showed mixed effects on patient health in developing countries, as evidenced by a significant reduction in the 7-day stillbirth rate and no significant change in perinatal mortality.

Community health: One study35 from India measured the health of communities, and showed a positive change in the community use of contraceptives (p<0.001).

Discussion

Continuing medical education programs, an essential component of the global health delivery system, have emerged as an appropriate way to change the educational issues of health providers and healthcare behavior within the healthcare system51. Studies have shown that continuing education programs can improve the knowledge, professional ability, and performance of health workers51-54. Despite a growing body of empirical research on the subject, the effectiveness and impact of continuing education programs in rural and remote areas has not been fully explored55.

This review examined the evidence for the effectiveness of continuing education programs in improving rural and remote health worker knowledge and performance, patient health, and community health. We included 17 published RCTs or quasi-experimental studies in high-income countries (n=3), upper-middle-income countries (n=8), lower-middle-income countries (n=5), and low-income countries (n=1). However, the review found limited evidence to support the overall impact of these continuing education programs on rural and remote health workers and patient outcomes. In particular, only two studies reported on the impact on patient health and only one study reported on the impact on community health. In addition, the results of this review should be interpreted with caution because of the risk of bias in the included studies.

The results reported showed that Chinese studies have focused more on improving the knowledge of health workers through continuing education programs than those from other countries. The seven studies from China34,37,42,44,47-49 that were included in the qualitative analysis all reported the outcome of health worker knowledge, 42.9% (n=3) reported on health worker performance, 14.3% (n=1) reported on patient health, and no studies reported on overall community health. In contrast, of the 10 published studies from other countries, 50% (n=5) reported the health worker knowledge outcome, 50% (n=5) reported health worker performance, 10% (n=1) reported on patient health and 10% reported on community health. It is clear that China’s current measures of the effectiveness of training for rural health workers are mainly concerned with improving the knowledge of health workers. This suggests that researchers, especially in China, should evaluate the effectiveness of continuing education programs for health workers in rural and remote areas in terms of health worker knowledge and performance, patient health and community health.

Considering the large variation in the types of included studies and outcome indicators, only two of the nRCTs37,44 from China included in our meta-analysis reported knowledge awareness rate as an outcome. The results showed that in China, continuing education programs contributed to improve rural and remote health worker knowledge compared to no intervention. Although the statistical heterogeneity of the two studies was small, the number of studies was insufficient to explain the effect. In addition, both of the studies were at risk of bias on random sequence generation, and one was also at risk of bias on allocation concealment. This suggests that the level of knowledge of rural and remote health workers as an indicator in this area needs to be further investigated in a large-scale study to reduce the associated bias and thus better elucidate the effectiveness of continuing education programs for rural and remote health workers on this outcome.

The narrative synthesis results suggest that in most of the included studies, continuing education programs may have contributed to improved rural and remote health worker knowledge and performance compared to no intervention. Knowledge improvement covers a wide range of areas, including clinical medicine, public health, general skills and pharmacy. Improvements in knowledge in clinical medicine are evident in the treatment of common diseases among health workers. In the area of public health, there was a significant improvement in the knowledge of health workers in rural areas in the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases (hypertension), infectious diseases (HIV and tuberculosis), maternal and neonatal care, and immunization after receiving continuing education programs. There was also a significant improvement in knowledge of medical science research and pharmacology (antithrombotic drugs for ischemic stroke) among health workers in rural and remote areas. Performance improvements were also seen in the areas of public health, general skills, and pharmacy. In the area of public health, significant improvements in immunization skills, neonatal and maternal care skills, mental illness (depression assessment), and screening for infectious diseases (tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases) were seen among rural and remote health workers compared to the control group.

Moore et al56 pointed out that the evaluation of the effectiveness of health workers’ continuing education should not be limited to health workers’ performance, but should be based on a multidimensional evaluation of health workers’ performance, competence, patient health status and community health. Of the 17 studies we included, only two33,34 reported on the impact on patient health and only one35 reported on the impact on community health. Other studies have only looked at the impact on the knowledge and performance of health workers. Clearly, little attention has been paid to the ultimate goal of improving the knowledge and skills of health workers, which is to improve health outcomes for patients and communities. However, one of our included studies34 showed that continuing education programs in rural areas significantly improved blood pressure control and significantly reduced the prevalence of hypertension in patients with hypertension. One included study35 showed that continuing education programs in rural areas resulted in positive changes in contraceptive use in the community. However, the number of studies included means that it is not possible to conclude with certainty whether continuing education programs in rural areas have a positive impact on patient and community health. In addition, it is worth noting that none of the original studies included looked at the cost-effectiveness of continuing education programs in rural areas and it is suggested that this aspect could be further explored in the future. Therefore, it is not clear from the available evidence in terms of patient and community health outcomes whether it is cost-effective to spend significant time, human, material and financial resources on continuing education programs for health workers in rural and remote areas. Therefore, there remains a need to continue to provide evidence of patient health in relation to continuing education programs in the future.

Gaps in urban or rural public health systems threaten the continuity of a healthy public health system57. It is important to actively implement public health services in rural and remote areas58. The results showed that most of the current continuing education programs in rural and remote areas involves public health-related content, which matches the basic situation in rural and remote areas. There are only two studies on clinical medicine and pharmaceutical continuing education programs in the world, and both are in China. More and higher-quality evidence is still needed to synthesize the effectiveness of continuing education programs for rural health workers in clinical medicine and pharmacy content. Two studies from Canada reported on the effectiveness of continuing education programs in general skills for rural and remote health workers36,38, and there are currently no studies from China reporting this outcome. However, studies from China showed rural and remote health workers still need to improve general skills59,60. Health workers in rural and remote areas, due to socioeconomic constraints, have little direct access to quality educational resources, and internet-based online education programs can help resolve this disparity in access. Many health workers have difficulties in general skills such as the use of computers and other electronic devices60,61. In addition, it may be more effective for health workers in rural and remote areas to develop the ability to access information if they are able to do so. Therefore, general skills can have an important impact on rural and remote health workers, and further studies are still needed to provide sufficient evidence to explore the impact of continuing education programs on this outcome.

Strengths and limitations

First, in contrast to other studies, we used a comprehensive and systematic search strategy to ensure the validity of the results obtained. Second, compared with the study of Dowling et al62, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of the included studies by a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods. Third, we systematically collected and analyzed RCTs and quasi-experimental studies on the impact of continuing education programs on health workers in rural and remote areas. Fourth, we not only considered changes in the level of knowledge and competence of health workers, but also included studies involving patient health and community health to comprehensively assess the effectiveness of continuing education programs in rural and remote areas. Fifth, we categorized the effectiveness of continuing education programs according to the content of continuing education programs and discussed it.

Some limitations of this study should also be mentioned. First, some studies were not included because of data availability limitations, although we did our best to search the databases and attempt to obtain relevant literature in the included literature references. Second, most of the included studies did not report biases such as those in selection and reporting, and there was an unclear or high risk of bias. Larger, higher-quality RCTs or quasi-experimental studies will therefore need to be designed to assess the impact of continuing education programs on health workers in rural and remote areas. Third, our previous findings were based entirely on currently included studies, and existing results need to be updated periodically as new relevant studies emerge. Fourth, the lack of consistency in the included literature measures means that outcome indicators other than knowledge awareness are only described qualitatively and future studies in this area should continue to be looked at to produce more convincing evidence.

Conclusion

Compared with no intervention, continuing education programs might be beneficial for rural and remote health workers’ knowledge and performance. Because of the limited number and quality of included studies, the impact of continuing education programs on patient health and overall community health is unclear. There is no doubt that more high-quality research is needed to fully elucidate the impact of continuing education programs for health workers on patient health outcomes in rural and remote areas.

Funding

This research is supported by the General Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 72074103).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

You might also be interested in:

2010 - A national view of rural health workforce issues in the USA