Introduction

Rural medical education during all levels of medical training from student to fellowship has been found to promote careers in rural medicine1-4. However, due to the geographic maldistribution of the Australian medical workforce and medical specialty maldistribution5,6, many rural health services are limited in their ability to fulfil the supervision requirements throughout medical training, especially junior doctors.

Medical students have been successfully trained at sites of increased rurality through Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships (LICs)7,8. LIC learners are embedded in a range of clinical settings for an extended period, undertaking clinical experience for each discipline in an integrated manner rather than in sequential block rotations9. This flexible approach sees the learner exposed to a range of clinical settings and disciplines within a given week, facilitating continuity of supervision over the clerkship duration10,11. LIC programs have been found to promote patient centredness, facilitate active participation in clinical skills and patient care, embed the learner as an authentic healthcare team member, produce academic results equivalent to block rotations and foster positive rural workforce outcomes2,7,8,11-13.

Longitudinal medical training has yet to be broadly applied to intern programs, with Portland District Health (PDH) being among the first health service the authors are aware of in Victoria to implement such a model. PDH developed and implemented this model based on their desire to grow their own medical workforce and identified the intern year as a key component to build a local rural generalist training pathway. The ‘bookends’ of the rural generalist pathway – medical students and general practice registrars – have been trained there for almost a decade but, prior to the introduction of this program, prevocational training had been the critical missing link. Due to supervision requirements the health service was not able to deliver an intern program using the block rotation model, so drew on their experience training third-year medical students from Deakin University’s LIC program to design a longitudinal intern program that could mitigate supervision issues inherent in block rotation structures.

The objective of this project report was to describe the program and experiences of participants involved during the initial year (2021).

Setting

Portland’s rurality index by the Modified Monash Model is MM4 (Medium rural town)14. The intern program operates across PDH and Active Health Portland (AHP) with core discipline exposure (general surgery, general medicine and emergency medicine) at PDH and the non-core discipline of general practice at AHP.

PDH is a rural integrated Victorian health service located within the Glenelg Shire (population catchment 19 621)15. PDH consists of acute, primary, and community health and aged care residential services16.

AHP, an independent health service, is co-located within the same health precinct. AHP offers a range of general practice and primary health care services and is a teaching clinic for medical, nursing and allied health students and general practice registrars17.

Methods

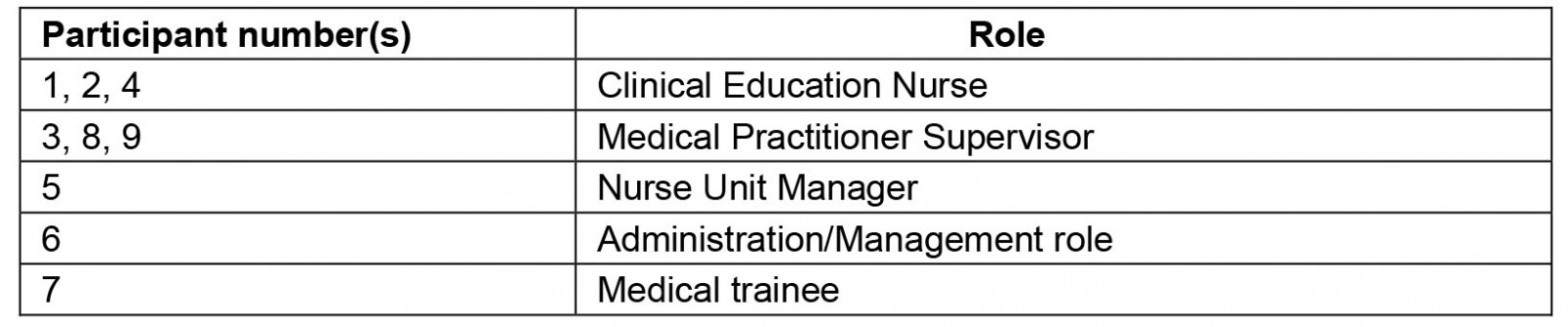

A descriptive case study methodology was employed as it allows for an in-depth, multi-faceted exploration of a phenomenon in real-life settings, utilising multiple sources of data18. Data sources included qualitative interviews with staff and students involved in the program and the review and description of documents associated with the program, such as rosters, accreditation submissions and role descriptions (Table 1).

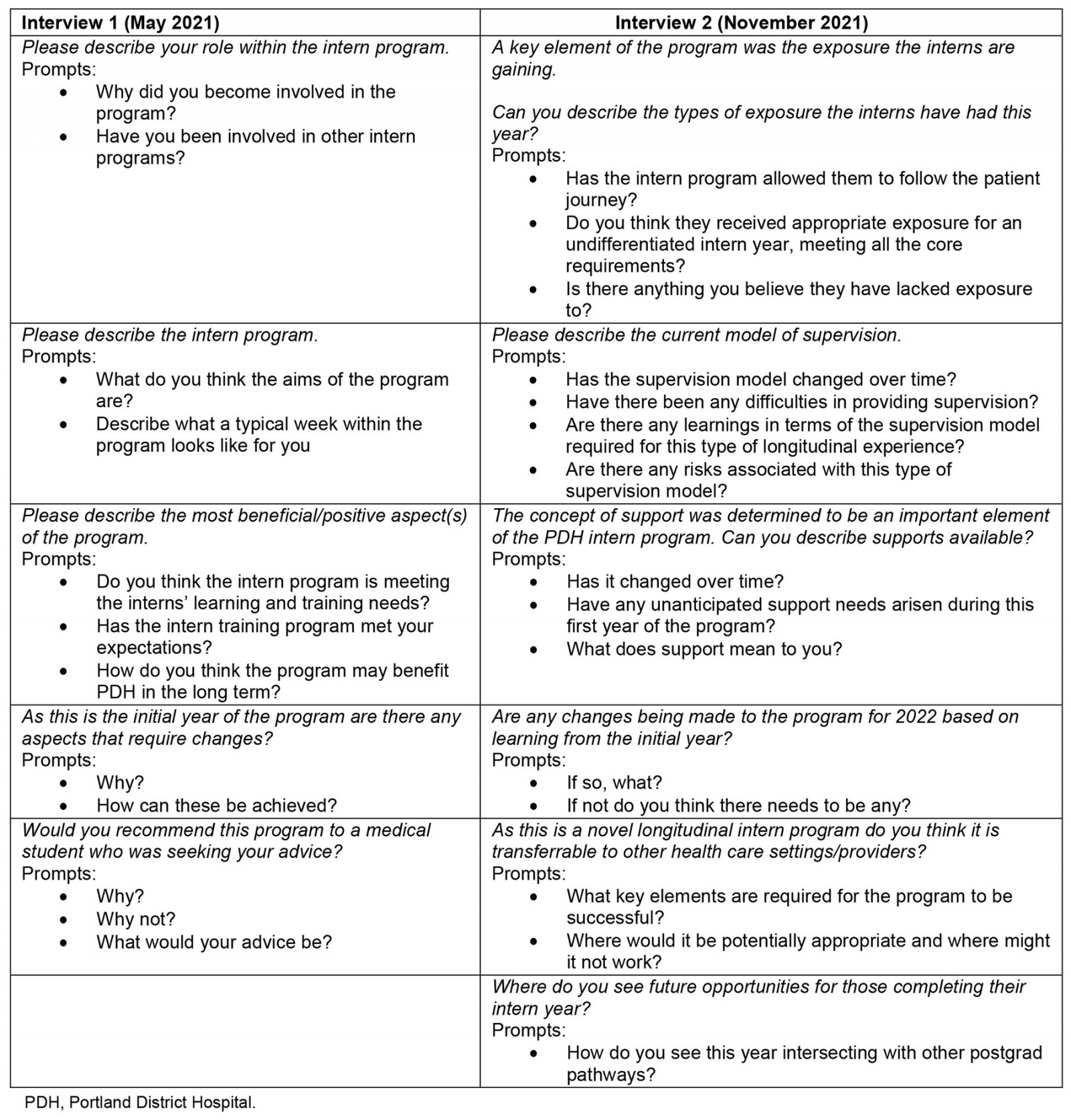

Participants were recruited by purposive sampling, with invitations to participate emailed by DH to individuals involved in the intern program. Interested participants directly conducted JB to arrange an interview time. One-on-one, in-depth, semi-structured phone interviews were conducted by JB at two time points during the initial year of the program (May and November 2021) to determine perceptions of the program and any changes over time. All participants received a plain language statement outlining the study objectives, participation requirements and consent process prior to participating in the study. The interview guide, developed by the research team, outlined topics and questions for exploration, inclusive of probes aligned with the research objectives19. An iterative process facilitated the development of the interview guide for the follow-up interview. Themes generated from the first phase of interviews were explored further to enhance understanding of the participants experiences (Table 2).

Interviews were audio-recorded, with transcribed interviews transported into NVivo 12 (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo) to supplement analysis. Interviews were de-identified by JB prior to data analysis to maintain confidentiality and mitigate any pre-existing relationships between researchers and participants. Transcripts were sent to all participants for review and approval prior to analysis. Two researchers (JB and LF) separately undertook reflexive thematic data analysis, inductively coding the transcripts to generate themes. Next they came together to review themes, re-exploring codes and themes across the entire dataset, clarifying central organising concepts and ensuring each theme provided something distinctive19. The entire research team then worked together to develop a consensus on themes.

Table 1: Roles of study participants involved in Longitudinal Integrated Clerkship program

Table 2: Indicative interview script

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by South West Healthcare Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC)

(reference number 2021-02).

Results

Accreditation review

Within Australia, health services require accreditation from their state based Postgraduate Medical Council (PMC) to establish an intern program. This involves submitting documentation for each discipline including application for accreditation, intern role description and supervisor role description. This is followed by a survey team site visit20.

The survey team concluded that the program met the mandatory intern training requirements, granting accreditation for 2021–2022 with continued monitoring.

Program design

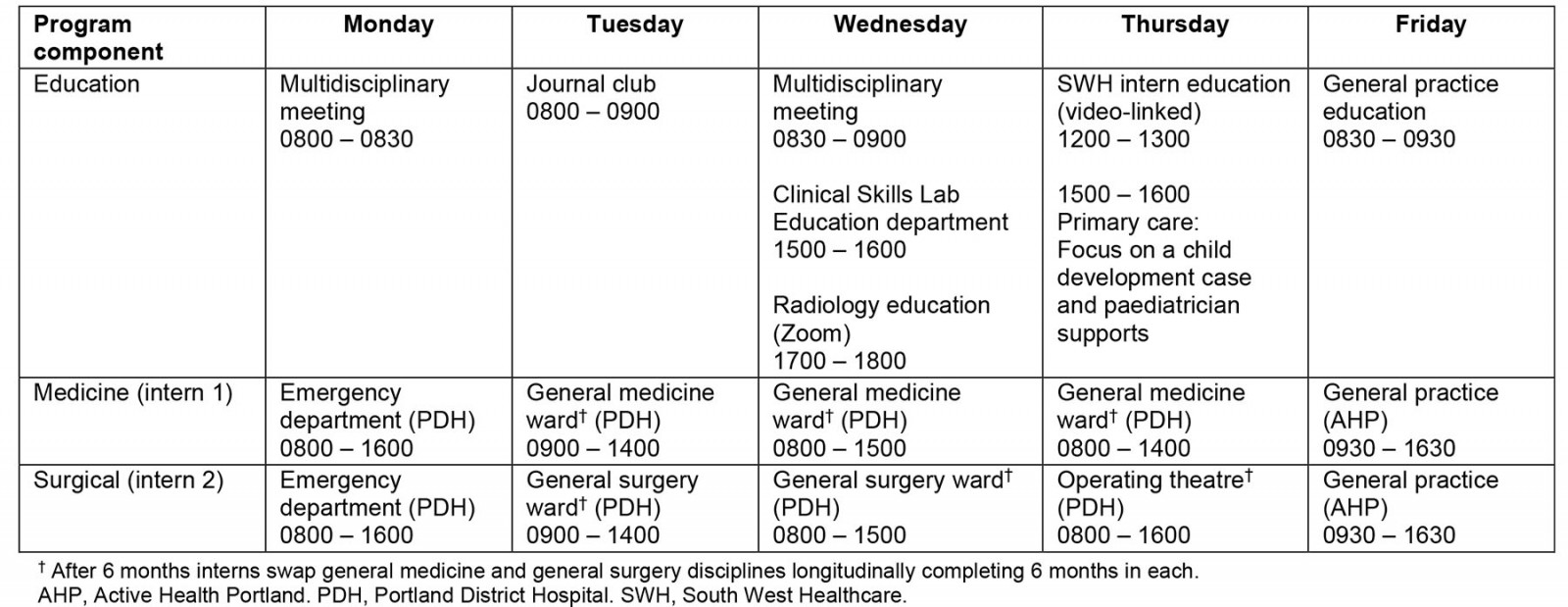

Two interns were employed full time. A typical week saw interns move between a range of clinical settings and disciplines.

Interns spent Mondays in the Urgent Care Centre (UCC), which provided the Emergency Medicine component of the program. They were directly supervised by a Fellow of Australasian College for Emergency Medicine (FACEM). During the middle of the week (Tuesday–Thursday) interns were assigned to either general surgery or general medicine, inclusive of inpatient and outpatient responsibilities (Table 3). Each intern spent 6 months in each setting and then swapped disciplines. Consultant physicians and surgeons provided supervision, with interns also attending cases within the UCC.

On Fridays, interns were in general practice at AHP participating in parallel consulting supervised by a senior general practitioner. Traditionally, the non-core component of an intern year consists of two hospital-based rotations; however, rotations in general practice have started to become more common in rural intern programs, recognising the value of primary care experience for junior doctors21. Based on this and the long-term vision to create a rural generalist training pathway PDH elected to include only one discipline, general practice as their non-core rotation.

Embedded within the roster was a comprehensive education program with protected learning time within the clinical skills education centre, attendance at multi-disciplinary meetings, journal club, local tutorials, and access via video conferencing

to intern tutorials at regional and metropolitan hospitals.

Table 3: Example of weekly Longitudinal Internship Clerkship program roster, 2021

Qualitative interviews

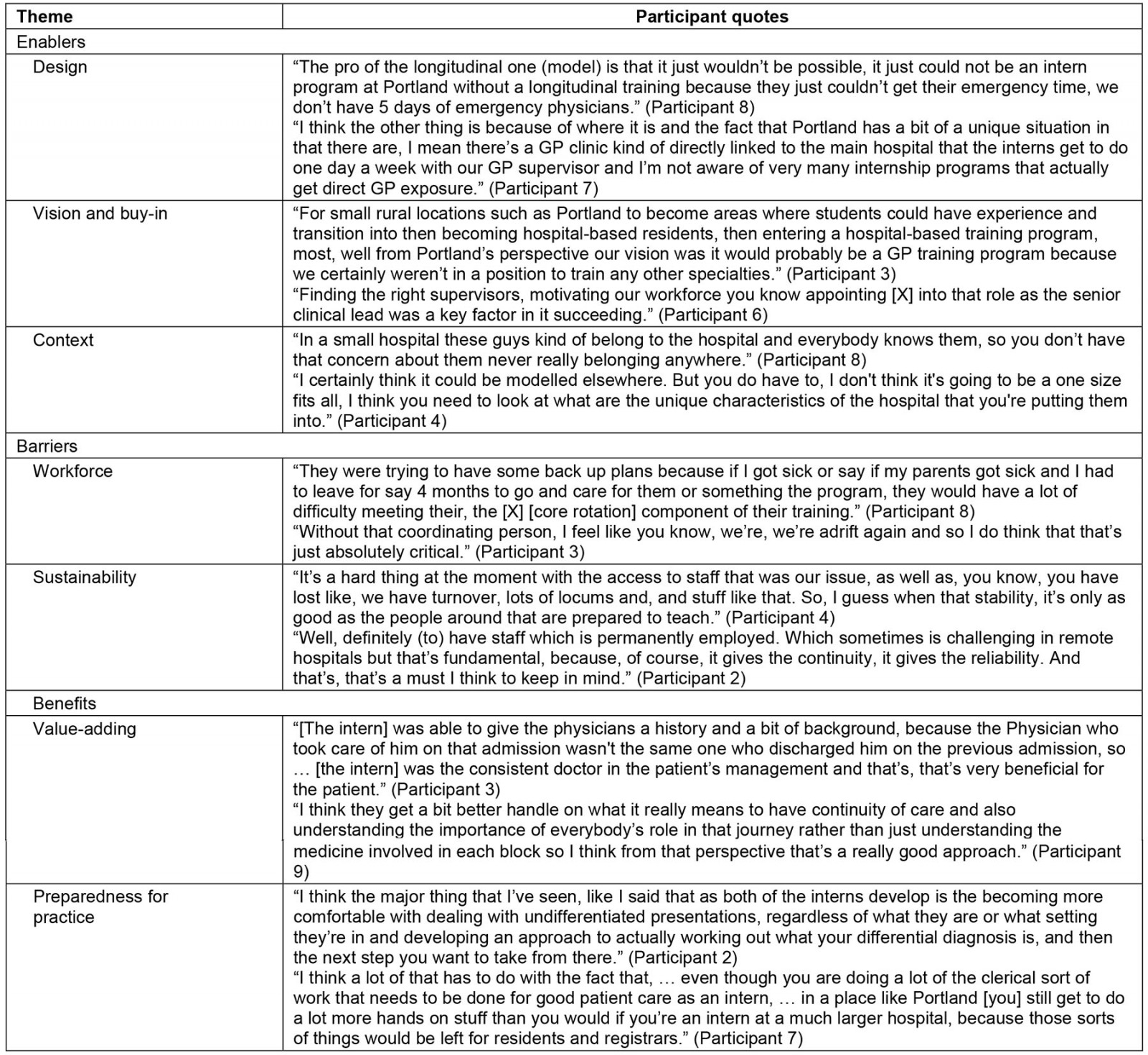

The interviews with nine participants highlighted the program's enablers, barriers and benefits. Participant quotes from interviews are presented in Table 4.

Table 4: Participant quotes related to enablers, benefits and barriers

Enablers

Design: Participants highlighted that the longitudinal design of the program was a primary facilitator in meeting the accreditation and supervision requirements. This allowed supervision requirements for emergency medicine to be met despite only having a FACEM present for 1 day per week.

Vision and buy-in: The employment of a dedicated program coordinator was described as translating the organisational vision into reality and helped facilitate staff buy-in to the program.

Staff buy-in also allowed for collaboration across health services (PDH and AHP). Despite the services being independent, both entities worked together to develop a program focused on providing the intern with an undifferentiated intern year in both the hospital and primary care setting aligned with the vision of creating a local rural generalist pathway.

Context: The smaller size of the health service was described as an enabler of the program as it was thought to foster a sense of belonging for the interns and allowed for flexibility within the program. The interns were felt to be well known throughout the hospital, being seamlessly attached to multiple settings/healthcare teams simultaneously. Participants felt the longitudinal model may not be transferrable to larger health services, fearing that the intern may never feel like they belonged anywhere. The model was felt to be transferrable to other similarly sized rural health services with adaptation to the local context. It was suggested the longitudinal model may be suitable for other spheres of medical training such as general practice.

Flexibility within the program enabled program adaptations to be made in real time, with the ability to be responsive to interns’ training and learning needs.

Barriers

Workforce: Workforce shortages were described as a significant threat to the program. If a supervisor was away, the flexible and integrated nature of the program allowed for the intern to be relocated to another department, but participants were concerned and unaware of what contingencies were in place should a supervisor be absent long term.

During the second phase of interviews the absence of a dedicated clinical program coordinator was described as detrimental to the program. As the program is conducted over multiple settings, the program coordinator was described as integral to the success and sustainability of the program to facilitate communication, meet accreditation and intern learning requirements and as an avenue of support for interns and staff.

Sustainability: The tenuous nature of the medical workforce and small number of interns was described as compromising the sustainability of the program. As the overarching aim is to build a rural generalist pathway and retain trainees long term, there was potential for workforce gaps in the program if the interns relocate after a year.

Benefits

Value-adding: The program was described as adding value for both staff and patients. Interns as members of interprofessional teams facilitated vertical and horizontal integrated learning, recognising that all team members were learners and could learn from each other.

Interns working across multiple settings simultaneously was felt to improve the continuity of care for patients. Participants described numerous circumstances where the interns were the consistent doctor in the patient’s care, as they had been part of the patient’s journey across multiple clinical settings. Program structure was felt to facilitate the interns’ understanding of continuity of care, valuing the importance of the entire healthcare team’s role in the patient journey.

Although participants highlighted that the interns were supernumerary and not included in medical workforce planning, they did acknowledge their progression over time allowed them to provide a meaningful contribution to the workforce, especially in the UCC and general practice, where they were involved for the entire year.

Preparedness for practice: Participants felt the interns’ preparedness for practice was enhanced by the breadth of exposure the program offered. This exposure enabled the interns to grow in confidence, improving their ability to deal with undifferentiated presentations, particularly in a rural context.

Interns evolved from observer to active participant during the year. This was thought to be facilitated by a flat, hierarchical structure, enabling interns to form sustained trusting relationships with the clinical teams, supervisors and patients, and an absence of other medical trainees competing for clinical opportunities.

Discussion

This project report demonstrates that it is possible to successfully deliver an internship at a rural health service through a longitudinal model. The development of this programs aligns with the philosophies underpinning rural generalist pathways, which aim:

to meet the specific current and future needs of Australia’s rural and remote communities … 22

This is achieved:

… through providing a regionally driven focus adaptable to different community contexts and provide opportunities for training and skills development supporting the needs of the town23.

Beyond the ability of a rural health service to train their own medical workforce, participants described added benefits of the program for the interns, health service and patients alike. These included clinical exposure relevant to the professional journey to becoming a rural medical practitioner, continuity of care, active participation in patient care, and interprofessional learning. These outcomes arose through the symbiotic relationship of both the LIC program design and rural health service context.

The rural health service context provided exposure to a broad range of patient presentations, across both low and high acuity settings, increasing confidence in dealing with undifferentiated patient presentations. This suggests the interns are developing the ability to manage clinical uncertainty, an imperative skill for rural generalist practice advocated by the National Medical Workforce Strategy6 and defined as a core competency of general practice colleges curricula24,25.

The improved continuity of patient care described is noteworthy given continuity has been found to promote patient-centred care, rapport building and compassion through the formation of trusting relationships over time. Continuity of care also provides the junior doctor with a greater understanding of the psychosocial impacts of patient care, particularly in relation to chronic disease management8. There is a growing concern that junior doctors undertaking block rotations have less exposure to continuity of care as training models have not adjusted to how healthcare delivery has evolved, with shorter patient hospital stays and delegation of patient care to outpatient settings such as general practice26. Not only did the longitudinal component of the internship allow for interns to follow the patient journey but also it provided longitudinal outpatient experience in general practice aligned with how modern health care is delivered.

This report illustrates the involvement of interns within an informal community of practice and illustrates the movement over time from peripheral to active participant and resultant ‘value-adding’ to the clinical team27,28. Participants frequently described examples of situated learning occurring within the community of practice, with interns contributing to and benefiting from vertically and horizontal integrated learning where everyone is viewed as an equal learner, with each level of experience bringing unique skills for the group to learn from29,30.

Despite the presence of a community of practice, the availability and continuity of supervision was identified as a potential threat to the intern program due to the reliance on a small number of primary supervisors. Further exploration of strategies to reduce this risk is warranted, including partnership arrangements with other regional health services to provide supervision or alternative placement contingencies should the need arise.

Limitations

Researchers did not employ the concept of data saturation but rather adhered to the concept of informational power, and believe the interviews provided a rich data set aligned with answering the research question19. The absence of interns as participants is a limitation. Barriers to their participation may have been time commitment and fear of identification. Further research will seek to investigate the experience of multiple cohorts of interns who have graduated from the program.

Conclusion

The intern year is a vital component for a rural generalist medical pathway, allowing medical students who train in the region to remain. Developing similar place-based medical training solutions in smaller rural communities is an important strategy in developing continuous local rural training pathways to develop and retain a rural medical workforce.

Reflexivity statement

Researchers were experienced in longitudinal medical education models. JB is a qualitative researcher focused on rural medical education and is employed in a rural LIC university program. LF is an experienced medical practitioner and educator employed within a rural LIC university program. Both JB and LF have conducted qualitative and quantitative research into outcomes associated with the LIC clerkship model. DH is an experienced medical educator and was previously a PDH staff member involved in the development of the PDH internship program.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Conflicts of interest

Debra Hobijn was an employee at Portland District Health involved in the development and delivery of the intern program.

References

You might also be interested in:

2014 - Practice intentions of clinical associate students at the University of Pretoria, South Africa