Introduction

The supply, shortage and maldistribution of healthcare professionals, such as doctors, nurses and allied health professionals, continue to impact the health and wellbeing of rural and remote communities globally1-4. Pharmacists seek to serve and support rural and remote communities and, in some cases, may be the only health professionals available in those communities5-8.

Pharmacists are recognised as providing medication dispensing while also increasing access to primary health care services including vaccinations, chronic disease management, wound care, oral health care and mental health support9. As such, pharmacists represent an integral component of healthcare access, particularly in rural resource-limited communities10-12. The recruitment and retention of pharmacists has been a concern for some time, in particular in rural communities, due to undersupply and workforce maldistribution5-7. Their importance is amplified in areas where they may be the only constant healthcare provider in a rural community7,13,14.

Several strategies seek to improve rural and remote healthcare provision; however, despite these efforts, rural communities remain disadvantaged due to poorer healthcare access15. Initiatives that have focused on recruitment and retention of the medical professions in rural and remote areas have yielded some success1,16,17. While lessons can be learned from these recruitment strategies, there is a need for targeted recruitment and retention interventions for pharmacists6,16,18.

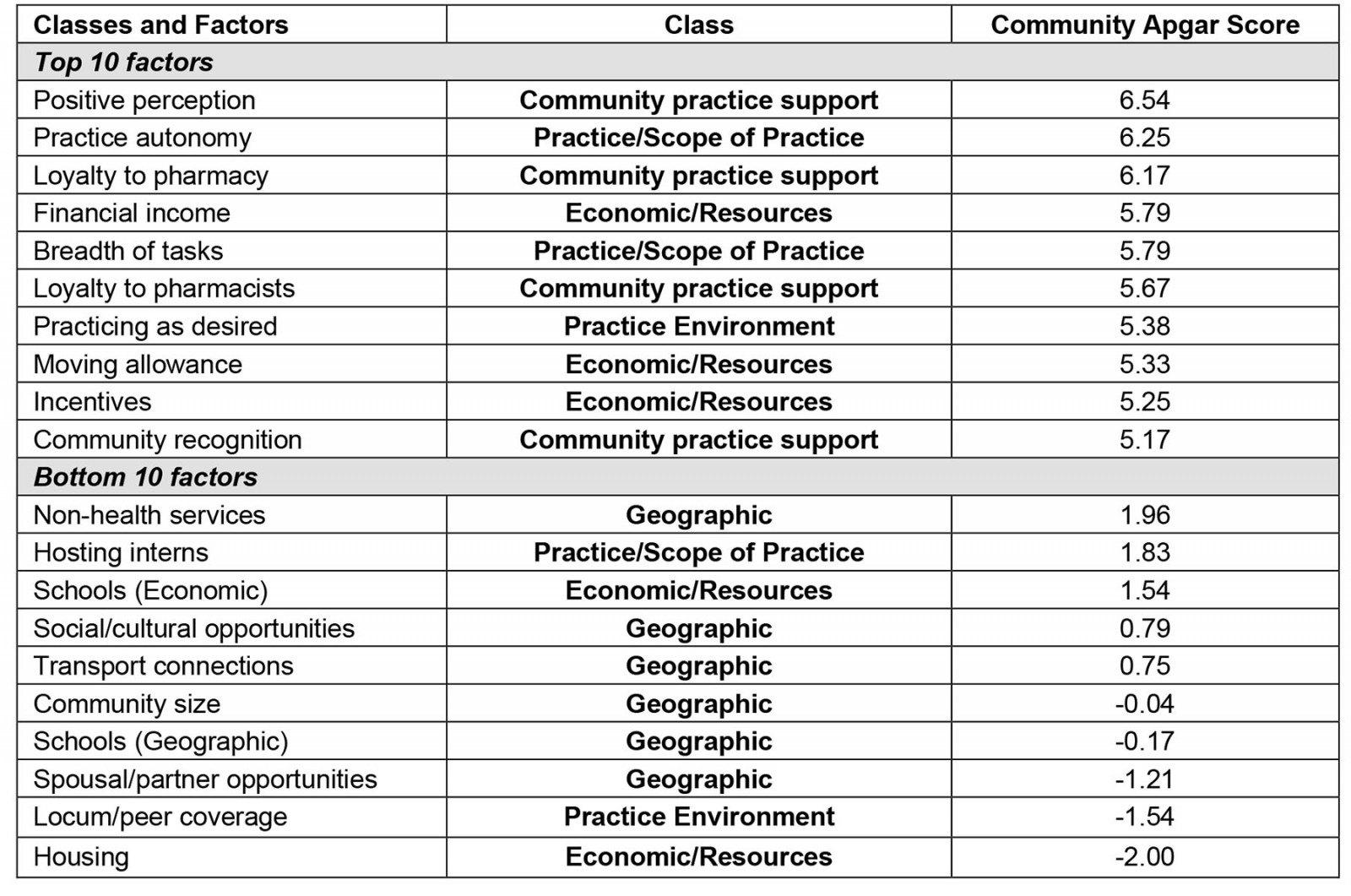

Recent research has identified that unique factors, such as enabling pharmacist-directed change, having broad scope of practice and providing adequate coverage for personal leave, have become more evident18,19. Specifically, these insights were gained through the Pharmacy Community Apgar Questionnaire18. In the present study, the quantitative data identified a hierarchy of key factors, both advantages and challenges, that are considered essential for establishing and sustaining a regional and rural pharmacy workforce18.

The advantages were associated with financial income, practice autonomy, breadth of tasks, perceptions of the community, loyalty to the pharmacy and its pharmacists, along with community recognition. Conversely, the challenges were linked to spousal or partner opportunities, lack of proximity to quality schools, social or cultural opportunities within a community, transport connections, community size, housing, and locum coverage and hosting interns18. Overall, these findings highlighted what capabilities, resources and gaps individual community and health are pharmacies need to assist or develop to improve recruitment and retention of pharmacists.

Despite our developing awareness regarding these key community assets and capabilities, there is a need to extend our understanding regarding the underlying reasons related to these key factors18,19. The aim of this study is to develop a deeper understanding of pharmacists’ perspectives about factors influencing the recruitment and retention of pharmacists in rural and remote communities.

Methods

Study design

The exploratory study used a qualitative descriptive design with a structured interview approach, akin to a survey, where the guiding principles were phenomenological in nature20. This approach enabled key experiences to be explored through the voices of those who are embedded within the phenomena being studied. As such, the phenomenology principles enable description and interpretation of the fundamental structures of the lived experience of participants20. Reporting methods adhered to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines21.

Research setting

The research was undertaken in rural Tasmania and rural Western Victoria, which have similar populations (approximately 63 000 and 73 000 people, respectively) and geographical areas (22 173 km2 and 22 821 km2, respectively)3. Rurality was classified using the well-established Modified Monash Model, a health workforce model categorising locations by geographical remoteness and town size, where MM 4 is ‘medium rural town’, MM 5 is ‘small rural town’ and MM 6 denotes ‘remote’ communities22. Among the 13 towns, seven were located in rural and remote Tasmania (MM 4–6), while the remaining six towns were in rural Victoria (MM 4–5). Due to the potential identifiability of each participating town, service provider and participant, these have been grouped by state only to maintain anonymity. Each rural or remote town was not associated with tourism or large influxes of non-residents at certain times of the year. Data were collected between August and December 2021.

Participants

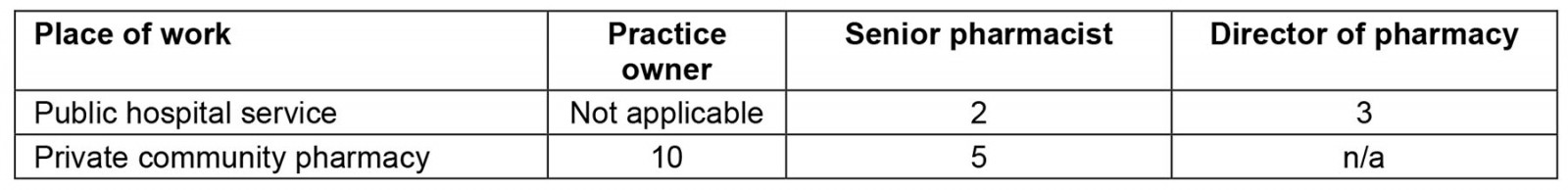

The sample consisted of 20 pharmacists purposively selected from known contacts or based on their geographical location and being critical in understanding the challenges associated with rural and remote recruitment and retention (Table 1). The number of years working as pharmacists ranged from 2 years to more than 40 years.

Table 1: Participants by work location and role within the pharmacy

Data collection

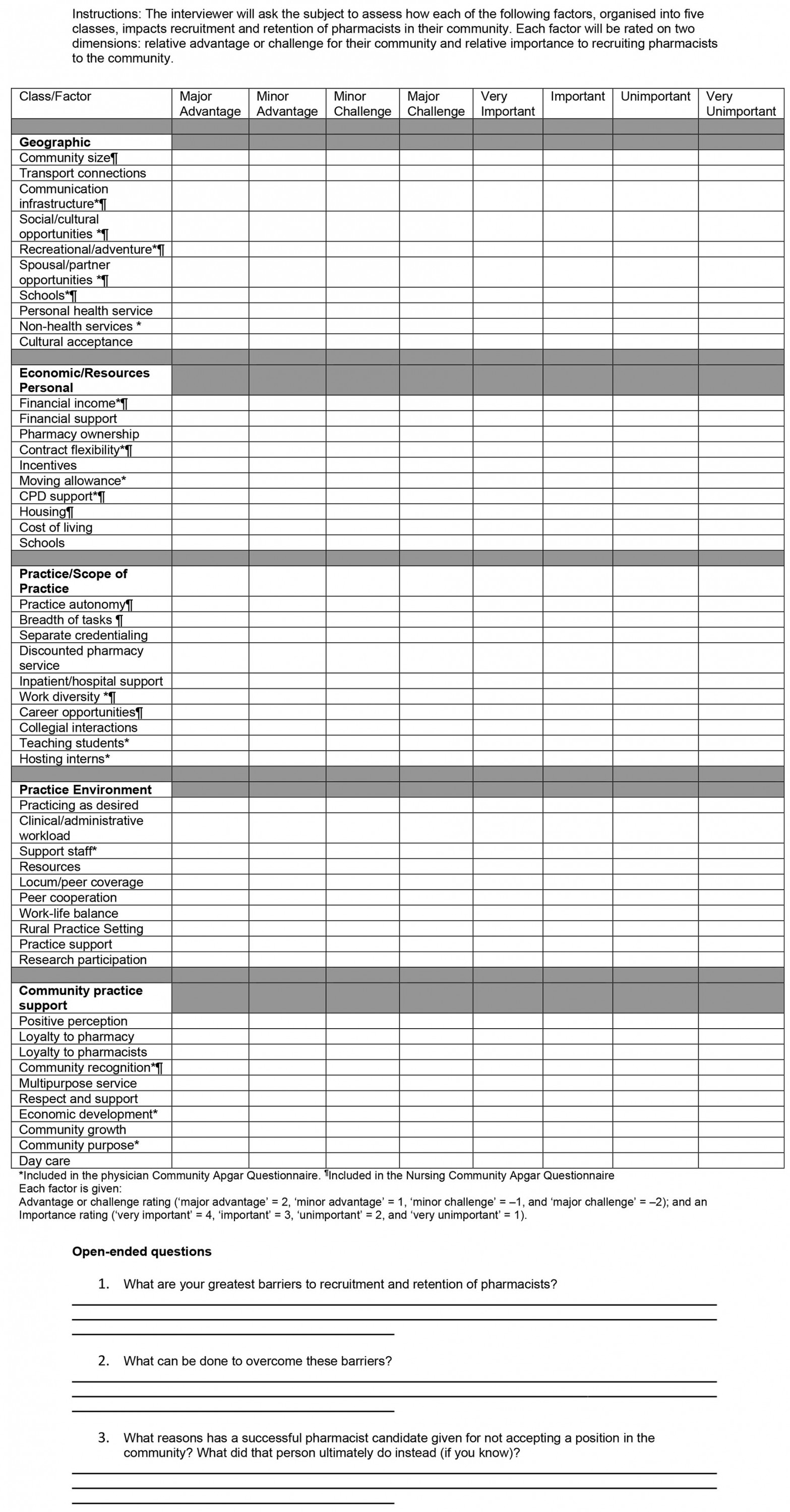

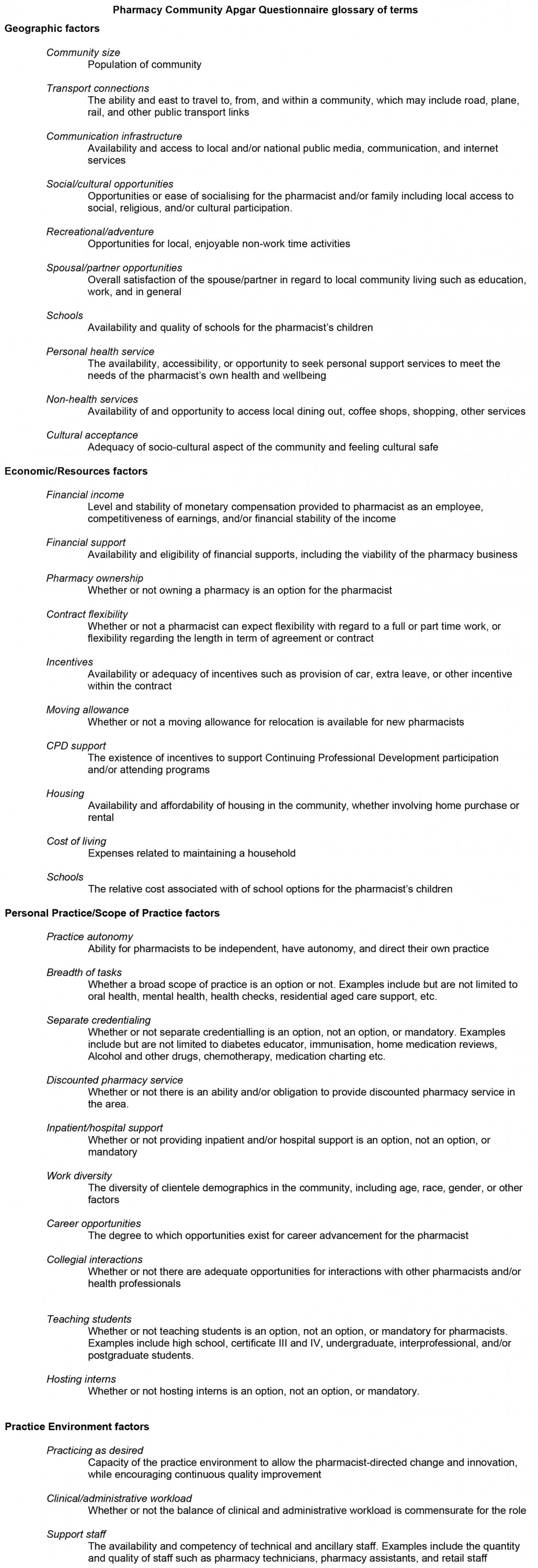

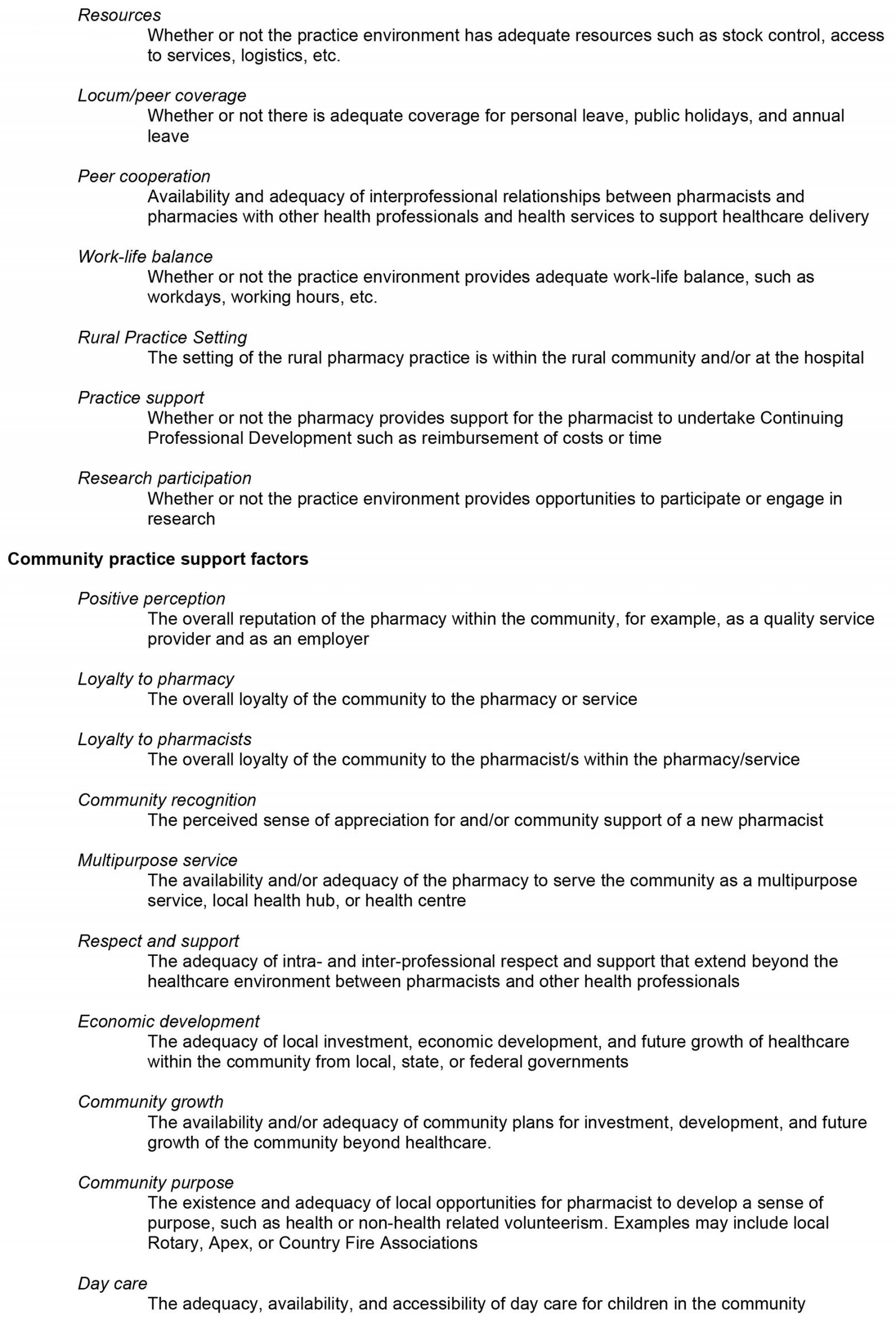

Interviews were conducted by a single author, a non-pharmacist academic who specialises in rural health workforce, between August and December 2021. The Pharmacist Community Apgar Questionnaire (PharmCAQ) guided the structured interview discussion and line of questioning with each participant7. The PharmCAQ consists of 50 individual factors that influence practice location decision-making and enables assessment of the resources and capabilities of rural communities to successfully recruit pharmacists, while identifying long-term retention strategies. The PharmCAQ provides a quantitative score for each factor, along with an overall score19. Specifically, within this article the qualitative data were used to provide a deeper understanding of each factor, whether an asset, capability or a challenge for pharmacist recruitment and retention. The PharmCAQ, which had been piloted, enables each factor to be qualitatively explored in depth through open-ended discussion that extends beyond the quantitative elements of the PharmCAQ (Appendix I)19. These open-ended questions are associated with factors that may be unique to each specific community that may have not been included within the first 50 factors.

Six of the 20 interviews were conducted face-to-face; however, due to COVID-19, travel limited researcher movement, thus the remaining interviews occurred by telephone or videoconferencing technology. Each interview was 30–60 minutes in duration and was audio- or video-recorded with consent. Fieldnotes were taken throughout and after the interviews were conducted.

Saturation was determined when new themes were no longer highlighted and new responses were not generating additional understanding. Data collection was continued until each of the identified sites had participated in the study by completing the PharmCAQ. Details about which factors scored the highest and lowest emerged (Appendix II).

Data analysis

All data collected, including responses from open-ended questions, were transcribed verbatim into Microsoft Word and member-checked, where participants were invited to review the transcription of their interview to confirm, revise or provide any additional comments that may have been omitted when first interviewed. Data were labelled according to the role of the participant (community and hospital pharmacists) and their interview order (1, 2, 3, etc). Interview data were collectively analysed by three researchers (DT, BP and HP) to ensure accuracy and truthfulness. Data were analysed thematically by following the procedural steps outlined by Braun and Clarke23 (verbatim transcription, extraction of significant statements, identify similarities in formulated meanings, group the similar meanings, create an exhaustive statement). Close contact with the data was maintained, which supported the identification of significant statements that pertained to the phenomena of interest. The meanings that were formulated, including responses to open-ended questions that were relevant to the factor of interest, were then clustered together to form themes.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by Federation University Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (#A21-023) and The University of Tasmania Human Research Ethics Committee (#26068). All aspects of the research adhered to the ethical principles for medical research on human beings, as set out in the Declaration of Helsinki. Each participant provided informed consent prior to commencement of data collection.

Results

The study was undertaken across two Australian states, one an island and each with diverse health systems. Despite this, there were only minor variations in the focus of the dialogue and, where these did occur, they were often associated with specific geographic elements relevant to the individual community or area within the state. Many commonalities associated with the advantages and challenges of recruitment and retention emerged. This was regardless of the differences between study areas and whether the participants were working in health services, in community pharmacies or were business owners. The findings were examined in relation to advantages and challenges associated with the recruitment and retention of pharmacists.

Advantages

When examining the advantages associated with the recruitment and retention of pharmacists, discussions centred on the economic or resources, practice or scope of practice, or the community practice support class of factors.

Economic and resource factors: These factors included financial income, incentives and moving allowance. It was highlighted that community pharmacists emphasised financial compensation that was above award rates (minimum pay rates and conditions of employment required by law associated with an occupation), and in some cases more than double the award was offered. Community pharmacists may also be eligible for future earning potential as an owner. Hospital pharmacists stated they were remunerated at the award rate, and this may be or be perceived to be below the total remuneration package received by community pharmacists. However, there were non-monetary incentives embedded within hospital awards in lieu of the higher salaries obtainable in the community setting. These included work flexibility, less financial risk, regular and certain levels of leave, or even longer term career pathways. Regardless of the differences in monetary compensation between hospital and community pharmacies, salary was a key asset for recruitment and retention.

Beyond remuneration, it was noted that there was a propensity for larger pharmacies or health services to have a far greater capacity to achieve superior staffing outcomes than those who were sole operators or much smaller services. Attracting permanent staff was a challenge and smaller pharmacies were bearing a greater proportion of the recruitment and locum costs, and for longer periods. Further, a high level of inequity existed between services in terms of what they could offer potential pharmacists as incentives or moving allowances, with larger rural centres having greater potential to attract staff due to population size and relative distance from major centres. However, this challenge enabled those further away from larger centres to create new and adaptive approaches to attract staff, such as working with other pharmacies in the area to share candidates, part-time options and greater work flexibility.

Practice and scope of practice: The second group of advantages encompassed practice autonomy and breadth of tasks. These factors relate to the ability of pharmacists to be independent, have opportunities to direct their own practice, while also having variety that will promote job satisfaction. It was shown that candidates are drawn to pharmacies or health services where an opportunity to be autonomous exists or is promoted, and where a high level of control over their own practice is viewed as an advantage. A participant stated, ‘There's a group of people that will find this ridiculously attractive … [they] learn a lot about themselves and are drawn to that type of independent practitioner status’ (Pharmacist 4, hospital pharmacy). It was suggested that it was the diversity of practice that occurs in the rural and remote workplace, compared to that of more metropolitan areas, that enables the development of early-career pharmacists or those seeking to work more rurally.

Nevertheless, it was suggested that, to work within a rural pharmacy either in the community or within a health service, ‘pharmacists need to be more well-rounded … [and] need to sort of have an understanding across all fields’ (Pharmacist 20, community pharmacy). Another added that beyond being well-rounded the role was a specialist-generalist role, so ‘you need to have either a good knowledge base or have a very good network of people that you can draw on, particularly when you have a something slightly unusual’ (Pharmacist 4, hospital pharmacy). As such, it was indicated that it is essential to create favourable opportunities for autonomous pharmacist practice, while the diversity and challenges in any workplace create opportunities to learn, develop and gain workplace fulfilment.

In addition, having a breadth of tasks in rural areas was identified as an enabler where a variety of experiences leads to a level of personal and professional growth, and enjoyment within the workplace. It was highlighted that such opportunities enabled career development and planning among more junior pharmacists, which was suggested as an opportunity to celebrate and promote as a rural pharmacy’s advantage.

Community practice support: The third group of advantages encompassed community practice support, which included the perception of the community, loyalty to the pharmacy and its pharmacists, along with community recognition. Each of these factors was centred on the relationship and respect the customers and patients had with the pharmacist, the overall pharmacy, and how this translated to ongoing business viability and the overall attractiveness of the pharmacy to a potential employee or business partners. One participant summarised this finding when stating, ‘I've certainly had feedback to support the fact that we're held in high esteem by members of the community, and I think [this] type of positive attitude will be an important consideration for someone looking to come and work with us’ (Pharmacist 4, hospital pharmacy).

Further, it was suggested that these relationships with healthcare consumers were vital in terms of the sense of belonging to the community itself. One pharmacist stated, ‘I can go down to the local supermarket … multiple people will want to stop and talk … [our pharmacists] have really strong grassroots in our community now’ (Pharmacist 16, community pharmacy). In addition, in rural communities, pharmacists have the opportunity to ‘… become really embedded and linked into a local community where they get maximum satisfaction from both a personal and professional level ... It's part of your practice of pharmacy, and it can be really rewarding’ (Pharmacist 16, community pharmacy).

Finally, relationships and sense of loyalty were often outwardly displayed among the various community members and healthcare consumers. Appreciation manifested as small gifts, which included chocolates, sweets, biscuits and cakes, right through to homemade or farm-grown produce, eggs, local wine and even lobsters in rural seaside communities. Although these small acts of kindness were provided regularly, it was suggested that the reciprocal nature of the community giving back to the pharmacist and pharmacy for their time and service to the community was what created a sense of belonging and fulfilment.

Challenges

The challenges associated with the recruitment and retention of pharmacists were also highlighted. The discussions encompassed the geographic, economic and resources, and the practice environment class of factors that were considered challenges; however, in some cases, these were described as advantages.

Geographical factors: The geographical class of factors included spousal or partner employment opportunities, proximity to schools, social or cultural opportunities, along with transport connections and community size. As such, respondents suggested that it was vital to ensure the needs of the pharmacist’s spouse or partner were being met, so that the pharmacist would more fully commit to employment and have a longer tenure in the rural community.

Beyond the needs of the spouse or partner, meeting educational requirements encompassed the geography and economics of schooling for children. Although these were considered as two separate factors in the PharmCAQ, they were often discussed together, given availability, proximity and quality of school in addition to the costs associated with sending children to school are interlinked. Often, decisions related to the community itself, the level of schooling available locally, perceived quality and wanting the best opportunities for children’s educational development. State-based primary schooling was considered sufficient for the needs of the children; however, when children were of secondary school age, a challenge arose if choices of schools were limited or considered poor quality.

Overall, if suitable education was not achievable within the community, particularly when children were reaching or at secondary school age, accessible, affordable and timely transport to a larger town where quality education was available would be considered as an acceptable alternative. Several pharmacists highlighted that the presence of a good bus network was vital to pharmacists when considering staying in the community long-term.

Community connection due to the size of a community or connection by way of social or cultural opportunities available were other recruitment and retention factors considered as challenges among pharmacists as identified through the PharmCAQ. Overall, these factors were considered important; however, it was highlighted that social and cultural opportunities differed between communities and, as such, were considered a positive for their presence or a negative for their absence. In many cases, social and cultural opportunities did exist and responses were often associated with participants' awareness of opportunities and their willingness or availability to participate, and if they felt welcome to do so.

Those who were familiar with, or who had grown up in, rural type communities were more likely to indicate they had experienced less challenges when compared with those who had more metropolitan experiences. When discussing community size, participants highlighted that connection to family and friends, who may be living within or in close proximity to the community, was more challenging among pharmacists than the size of the community, while connection was also associated with a pharmacist’s need or capacity to develop and nurture new friendships. One participant shared insight that resonated with several other participants, when they stated, ‘Well, it's challenging … I think there's supports within [town] culturally, just depending on what the person’s background is. [Town] has welcomed a lot of refugees and migrants, but if you're single or not a sport person there may be greater challenges in fitting in' (Pharmacist 11, hospital pharmacy).

Economic and resource factors: The economic and resource class of factors included housing and the cost of schooling for children, as previously discussed. Specifically, participants highlighted that rental accommodation, as a first option for a new pharmacist, was limited. However, if the potential candidate was seeking to purchase a home rather than to rent, it was indicated that there were more options available; however housing stock was becoming increasingly limited in rural areas. In one case, it was stated that the rental market was at zero percentage vacancy rate and rural towns had experienced a 12–30% increase in property prices, which in some cases meant that rental or home affordability for a pharmacist was commensurate with that in more urban areas.

To meet this challenge, several pharmacies or health services were providing short-term or longer term housing options; however, they were often only able to accommodate the pharmacist and their partner. Nevertheless, those who were considering rural employment were supported or at least provided with additional incentives or subsidies to meet the basic need of housing. Being able to do this was seen as a competitive advantage above other rural pharmacies. Pharmacist 20 (community pharmacy) said, 'I'm in a lucky position that we have a unit. I've got accommodation for a single or double, but it definitely couldn't take children. It's not big enough … So, I'm in the fortunate position'.

Financial support provided by the pharmacy, particularly rural pharmacies, was also discussed in detail as it impacted many aspects of recruiting and retaining staff. It was discussed that the pharmacy is often the only health service in town or where health consumers seek initial support for poor health; however, the services provided were not always compensated through current government rebates, which costs the pharmacy time and, in some cases, revenue. One pharmacist stated, ‘because of the lack of health care services in our area patients come to me … [and] I'm guiding the patient through the health care system, and it can take a lot of time … and I can't get paid for it because it doesn't fit the [government rebates for services provided]' (Pharmacist 17, community pharmacy). Although altruistic in nature, providing community support without adequate financial compensation was not sustainable or seen as a positive for candidates considering working in a rural pharmacy.

In addition, it was suggested there were government supports available to enable rural pharmacies to provide pharmacy services to rural communities by financially assisting eligible pharmacy owners. In some cases, participants spoke of a $10,000 intern training assistance package. Although helpful, several participants, such as Pharmacist 8 (community pharmacy) highlighted that it ‘… is not really covering all parts of the business’. Another participant, when speaking of assistance packages, indicated they did not bother and argued ‘these financial supports mean time and paperwork, too much government paperwork is a problem – it’s a cost benefit issue … and it’s not worth it’ (Pharmacist 3, community pharmacy).

Practice environment and scope of practice: The final class of factors embodied locum and peer coverage associated with the practice environment class of factors in the PharmCAQ, while hosting interns were embedded within the practice and scope-of-practice class of factors. Although within different factor classes, both were related to staffing and considered vital to pharmacists who may consider working rurally.

For some, getting locum coverage was challenged by both the direct cost of the locum and the location of their practice relative to a major population centre. For example, a participant stated, ‘… if I'm wanting to get a locum, they will not come for [dollar amount] an hour, and even if you offer [double], they won't come to smaller places. They don't like to travel too far’ (Pharmacist 8, community pharmacy). This sentiment was further explained by another participant: We’ve actually had nobody apply … you know people [ask] … ‘How far are you from [the city]?’… Our issues have always been about location’ (Pharmacist 10, community pharmacy).

Conversely, others described positive experiences with locums who have built up a rapport with their community over several years and know how to manage the service. In one case, the locum became the pharmacist for the hospital when the previous pharmacist retired. ‘I saw the ad for the job and applied before I came to see the health service. I had worked as a locum here before … so I knew what to expect’ (Pharmacist 11, hospital pharmacy).

Hosting paid interns was also highlighted as a key challenge that may impact on how an employment opportunity may be viewed. There was a real sense of value of hosting interns and the associated teaching of students, due to them representing the future workforce who may like to work in rural communities, but also due to the value they bring by enabling pharmacists to ensure contemporary practices are in place. However, both community and hospital pharmacies recognised the limitations they currently have in terms of staffing, including the size of the service, to support the training. Further, one participant highlighted that it was a lot of investment for potentially little return or that retaining an intern longer term was not financially viable. They stated, ‘I would love an intern, but it’s not that easy … and then the retention after training … we couldn't afford to have two full time pharmacists. So, the transition of future pharmacists is important and integral, but it is the ability to retain them afterwards which is limited’ (Pharmacist 18, community pharmacy).

Discussion

This study adds to the understanding of the advantages and challenges of recruiting and retaining pharmacists. Insights were linked to the advantages of financial income, incentives and moving allowance. Additional advantages include the degree of practice autonomy, breadth of tasks, perception of the community, loyalty to the pharmacy and its pharmacists, along with community recognition. Challenges associated with the recruitment and retention of pharmacists centred on the need for spousal or partner employment opportunities, having greater proximity to schools, access to social or cultural opportunities, along with good transport connections. Further challenges included housing, the cost of schooling for children, having adequate locum or peer coverage and opportunities to host interns.

Overall, financial compensation was emphasised as an essential enabler for potential candidates considering rural pharmacist appointments. This is consistent with previous studies that highlighted the importance of monetary compensation level and stability to ensure sustainable recruitment and retention of rural pharmacists7,24. A shortage of affordable rental accommodation or housing was identified as a challenge for rural pharmacists considering taking on a rural opportunity. Similarly to other studies, there is a very high demand for housing in rural areas in comparison with other geographical areas, which resulted in many employees deciding to leave a community25. This suggests that economic and financial incentives could help pharmacists move to and settle in rural areas.

Similar strategies highlighted within the findings are currently being implemented by some governments to build health professional loyalty in rural areas25. However, for more effective retention, in addition to one-off financial subsidies, financial viability of the service along with personal and professional strategies that promote long-term recognition must also be addressed7,26. Our study participants valued government financial and other support available for eligible rural pharmacies, but more sustainable funding was considered important to provide financial relief and sustain the service. Previous studies27,28 reported that financial models, such as cross-sector partnerships, have led to pharmaceutical supply and distribution services that enable profit margins or pooling of funds to supplement the remuneration of a sessional pharmacist. Such innovative approaches may provide practical solutions to sustain rural pharmacy services.

Rural pharmacists in Australia are facing difficult situations within their communities to remain viable29. One of the greatest challenges that was considered to impact on recruitment and retention of staff was locum or peer coverage, which has been reported in previous studies30. The Australian Government funded Rural Locum Assistance Program has provided locums so that rural health professionals, including pharmacists, can attend continuing professional development or take vacation leave31. However, relief coverage still emerges as a major concern for many rural pharmacies. Despite this, additional support and options to provide affordable relief coverage for rural pharmacists could be made available. For example, regional or state level locum tenens (placeholder) programs may encourage cooperative coverage relationships within geographic areas, both among retail pharmacies in neighbouring communities and among hospital and retail pharmacies18,32.

Hosting interns was considered a key challenge associated with an employment opportunity in rural pharmacies, which has financial and workload impacts for rural pharmacies to support training and offer ongoing employment beyond internship33. Acknowledging the challenge that rural pharmacists encounter, the Australian Government’s Intern Incentive Allowance for Rural Pharmacies has provided supports to community pharmacies or hospitals in rural areas to employ a pharmacy intern for a continuous period of 6–12 months, with maximum allowance of $5000 to $10,000. Additional funding of up to $20,000 is available for community pharmacies to support the continuous engagement of a newly registered pharmacist for 12 months33,34. Although there is evidence that undertaking a rural internship was the strongest predictor of future rural practice35, no research has evaluated if the financial support to pharmacies is sufficient to result in an increase in rural internships and future employment outcomes. The incentive has been valued by most pharmacists; however, greater regulation and transparency is required regarding how intern incentives should be spent by pharmacists, as the incentive pay may be absorbed by the business and not be used for its intended purpose36.

Autonomy and breadth of task opportunities can be a positive asset for pharmacies in attracting and retaining rural pharmacists8. It was highlighted that these opportunities for personal and professional growth enabled career development and planning among more junior pharmacists, suggesting this could be used to the rural pharmacy’s recruitment advantage. This is consistent with the findings of this study, which highlights that rural practice provides pharmacists with opportunities for personal and professional growth, which enabled career development and planning8.

Relationships and the sense of loyalty among the various community members and healthcare consumers, along with community recognition, were described as contributing positively to recruiting and retaining pharmacists in rural communities. This finding reinforces the existing body of literature among healthcare workers. These aforementioned enablers provide opportunities for promoting rural strengths to attract and retain pharmacists who are dedicated to the rural lifestyle and practice. Cosgrave37 and Malatzky et al38 provide insights into placed-based strategic approaches to support the recruitment and retention of allied health professionals. Concepts such as sense of place, place attachment and belonging-in-place are offered as potential solutions and are increasingly used to develop effective strategies.

Limitations

The qualitative focus of the study limits the degree to which the findings can be generalised to other contexts. Given the richly diverse physical, social and geographical extremes of Australia, we acknowledge that our focus on the south-eastern areas of the country may have more limited application in other states, especially in more remote areas or areas that are vastly different to the south-east corner of the country. Overall, while these findings provide insightful information, they may not be representative of all rural and remote areas of Australia and may have limited application internationally3.

Conclusion

This qualitative study has provided a deeper exploration of the meaning and experiences of factors that previous research has shown are considered advantageous or challenging to the recruitment and retention of pharmacists in rural areas. Through the voices of pharmacists living and working in rural areas, the findings underscore the multifaceted and complex nature of health workforce planning. Greater pharmacist recruitment and retention is enabled through adequate financial compensation and incentives, along with additional tax incentives for business and health services while examining sustainability innovations. Locum coverage and intern opportunities also require innovations a the local and state level to meet the needs of potential candidates considering rural practice. Lastly, rural practice that offers opportunities for professional development and the capacity to develop a broader scope of skills must be accompanied by efforts to enable schooling and spouse employment, while building community connection and sense of belonging for pharmacists and their families. Overall, the implications of these findings reveal that rural pharmacist recruitment and retention requires a multifaceted approach. Given the complexity and unique features of individual rural communities, solutions to challenges and building strategies will be best served by a whole-of-community ownership and approach. These local solutions should be facilitated within the framework of business and organisation innovation, supported in regulation with fit-for-purpose incentives and sustainable funding. Successful pharmacist recruitment and retention will benefit the whole of the community involved in the efforts.

References

You might also be interested in:

2013 - The role of risk theory in rural maternity services planning