Introduction

Aging in rural contexts is a global reality, but one that is still little studied. It is known that people who age in rural contexts have some characteristics that are different from older people who age in urban contexts. Aging in rural contexts can be even more challenging for cognition, physical function1-22, and with serious consequences for life purpose.

It is known that the aging process can often be accompanied by changes in cognition, which directly affects functionality and can have a negative impact on an elderly person's life purpose1,3,23-26. Having a life purpose is described in the literature as a protective factor for health, functionality and cognition in the elderly26.

Cognition, physical function and life purpose constitute an important triad for functional and successful aging, yet little is known systematically about this reality in elderly people who age in a rural context.

This systematic review of cross-sectional studies of the world's rural population describes the main characteristics and ways of aging in rural communities around the world, focusing on cognition, physical function, functionality and life purpose.

Methods

This systematic review followed the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement27; the protocol was registered in the PROSPERO international prospective systematic review database (PROSPERO: CRD42022311053). The full protocol for this study is available28.

Definitions

For the studies to be included in this review, they had to be cross-sectional and have been carried out with elderly people who aged in a rural context anywhere in the world.

Data sources and eligibility criteria

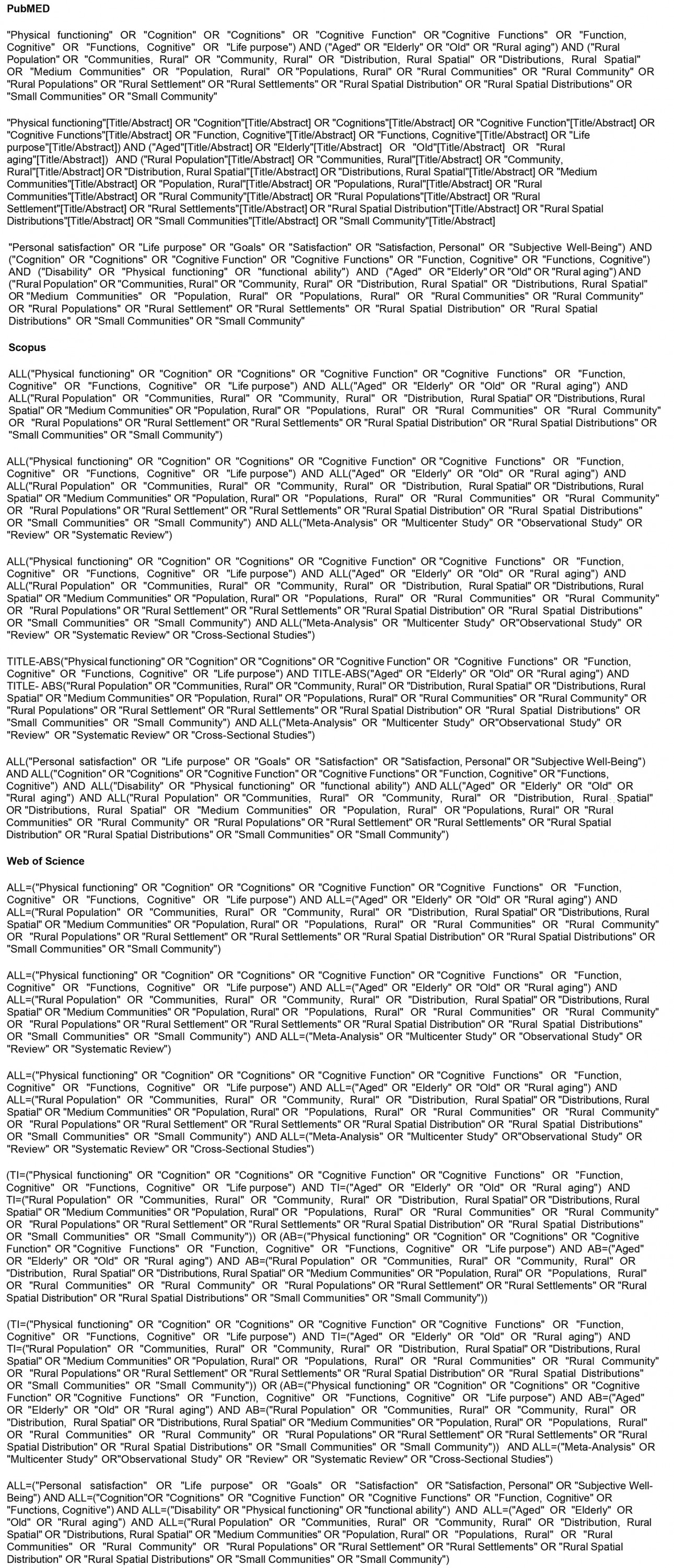

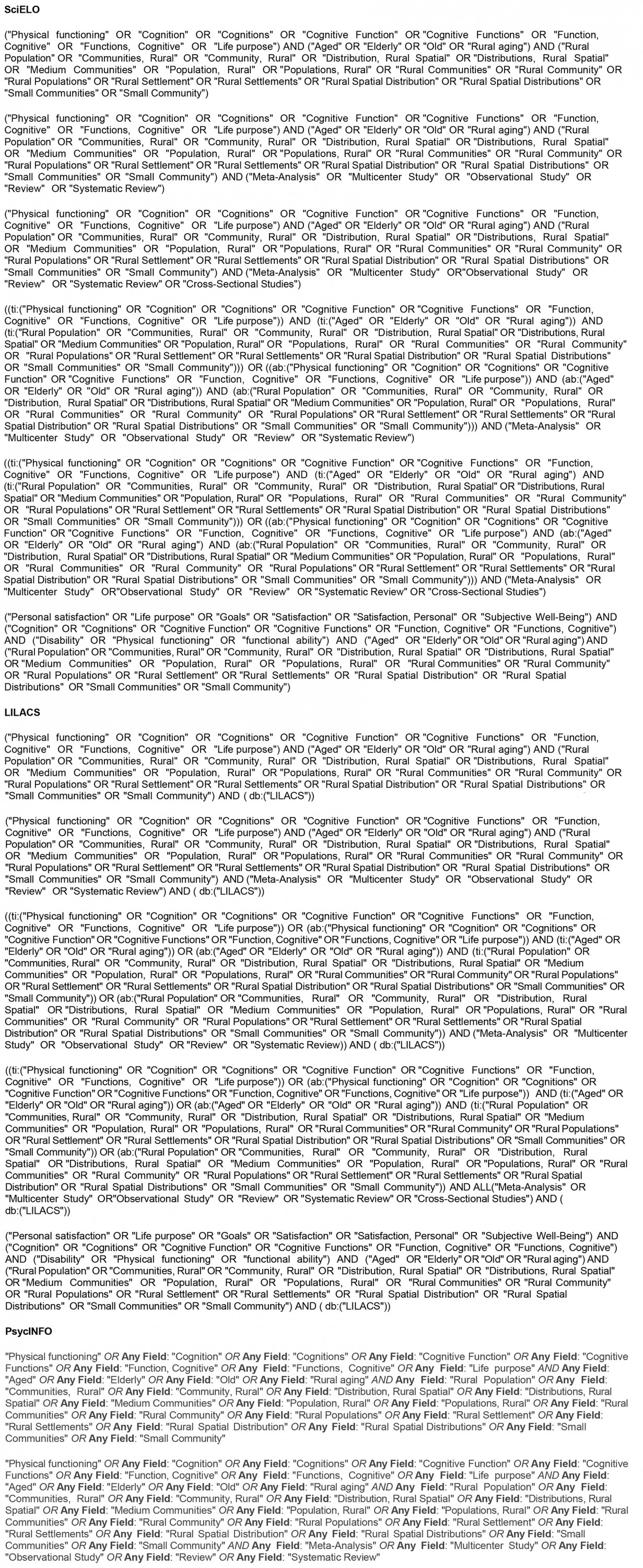

A systematic literature search was carried out using the following databases: PubMed, LILACS, PsycINFO, Scopus, SciELO and Web of Science.

The Rayyan software29 was used for the first selection of studies and the Observational Study Quality Evaluation (OSQE) tool30 was used to assess methodological quality and risk of bias. The search strategy was developed with the research group and the librarian at the University of São Paulo's School of Medicine and included the following search terms as well as the use of Boolean operators AND / OR: "physical functioning"; "cognition"; "cognitive function"; "life purpose"; personal satisfaction; subjective well-being; "aged"; "elderly"; "old"; "rural aging"; "rural population"; "communities, rural"; "distribution, rural spatial"; "medium communities"; "rural settlement"; "small community". The detailed searches can be found in Appendix I.

The inclusion criteria for the articles were studies showing prevalence of functional conditions, cognitive decline and life purpose in rural elderly people. The exclusion criteria were systematic review studies; methodological studies; instrument validation studies; and qualitative studies. The following information about the studies was recorded: author, year, gender of the sample, age in years, main characteristics of the population studied, country where the study was carried out, number of the sample and whether it assessed physical function, functionality, cognition and purpose of life in elderly people aging in a rural context. The information was organized and presented in tables.

Study selection process

Articles published up to April 2023 were considered.The primary analysis comprised analyzing the titles and abstracts that were available and uploading to Rayyan29. This assessment was carried out independently by the three study authors (HLMC, EBDL and IMBS), and when there was disagreement, the abstracts were discussed and a consensus reached. Secondary selection took place by reading of the selected articles in full by two independent reviewers (HLMC and ERAO) and confirmation by a third reviewer (AQ) when necessary. Publication bias was assessed using the OSQE analytical cross-sectional study quality.

Study evaluation

The OSQE, which measures study quality and risk of bias for cross-sectional studies, was used to evaluate the studies30.

The OSQE Scale evaluates 16 points of cross-sectional studies by assigning a star (point) when a question is addressed by the study30:

- Is the sample ideal in terms of both internal validity and representativeness?

- Is the cohort really one cohort or are there subcohorts, eg one exposed and one unexposed?

- Independent variable: validity of the assessment; presence of exposure

- Dependent variable: validity of the assessment

- Blinded evaluation: Was the exposure unknown to the evaluator? Were subjects excluded when the outcome was present at the start of the study?

- Is the follow-up long enough to assess the outcome? Is the outcome assessed continuously? Is loss to follow-up likely to introduce bias? Did the authors use methods to adequately deal with missing data (including loss to follow-up)?

- Is there conflict of interest (eg funding from the pharmaceutical industry or researcher affiliated with the pharmaceutical industry)?

- Does the statistical analysis control for relevant confounding factors? Did the reporting of results follow a protocol; in other words, were only intended prior analyses reported?

- Unlike selective harvesting, are effect modifiers analyzed correctly?

- Is the sample size sufficient, observing the calculations/explanations provided by the authors?

Results

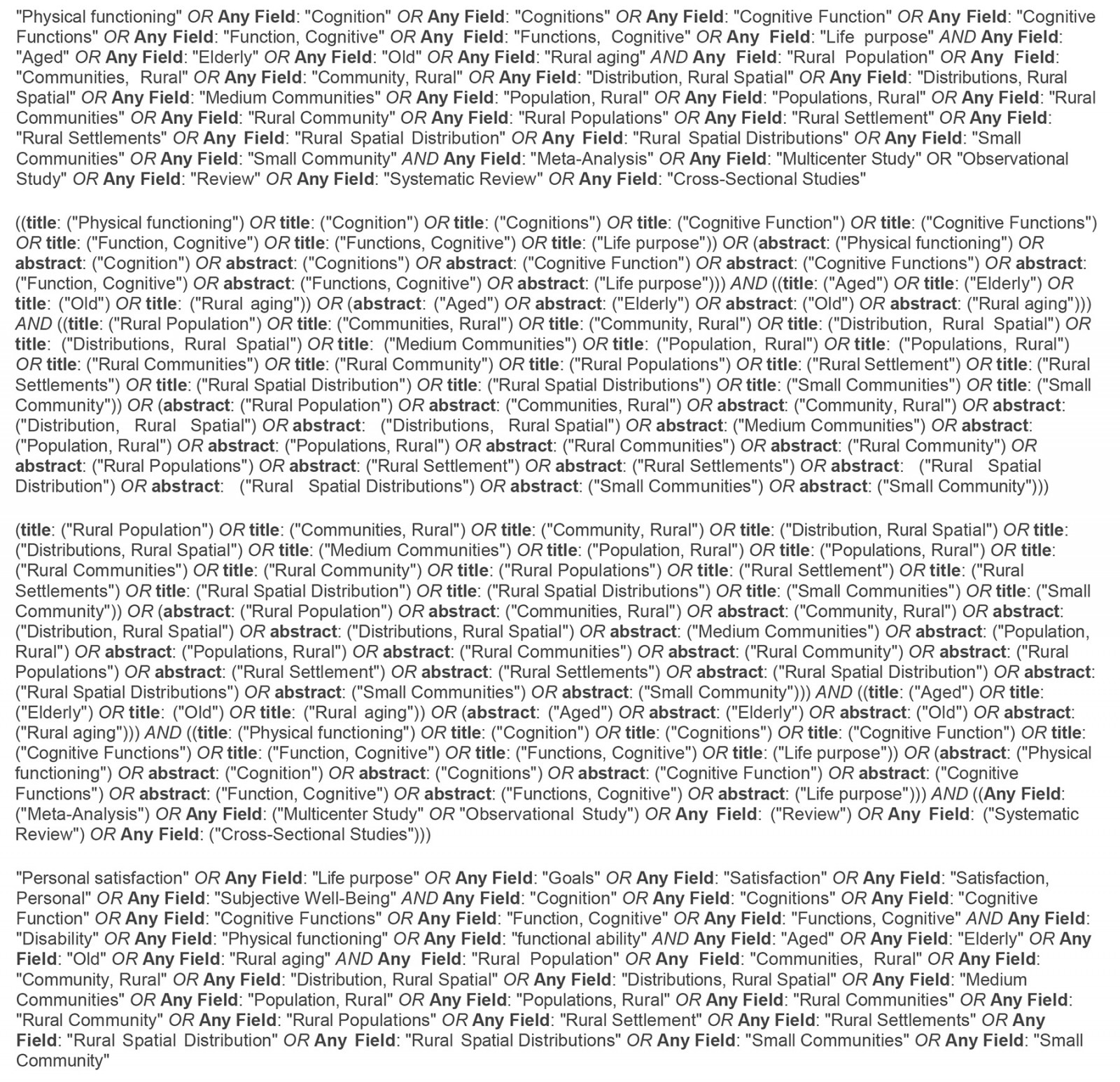

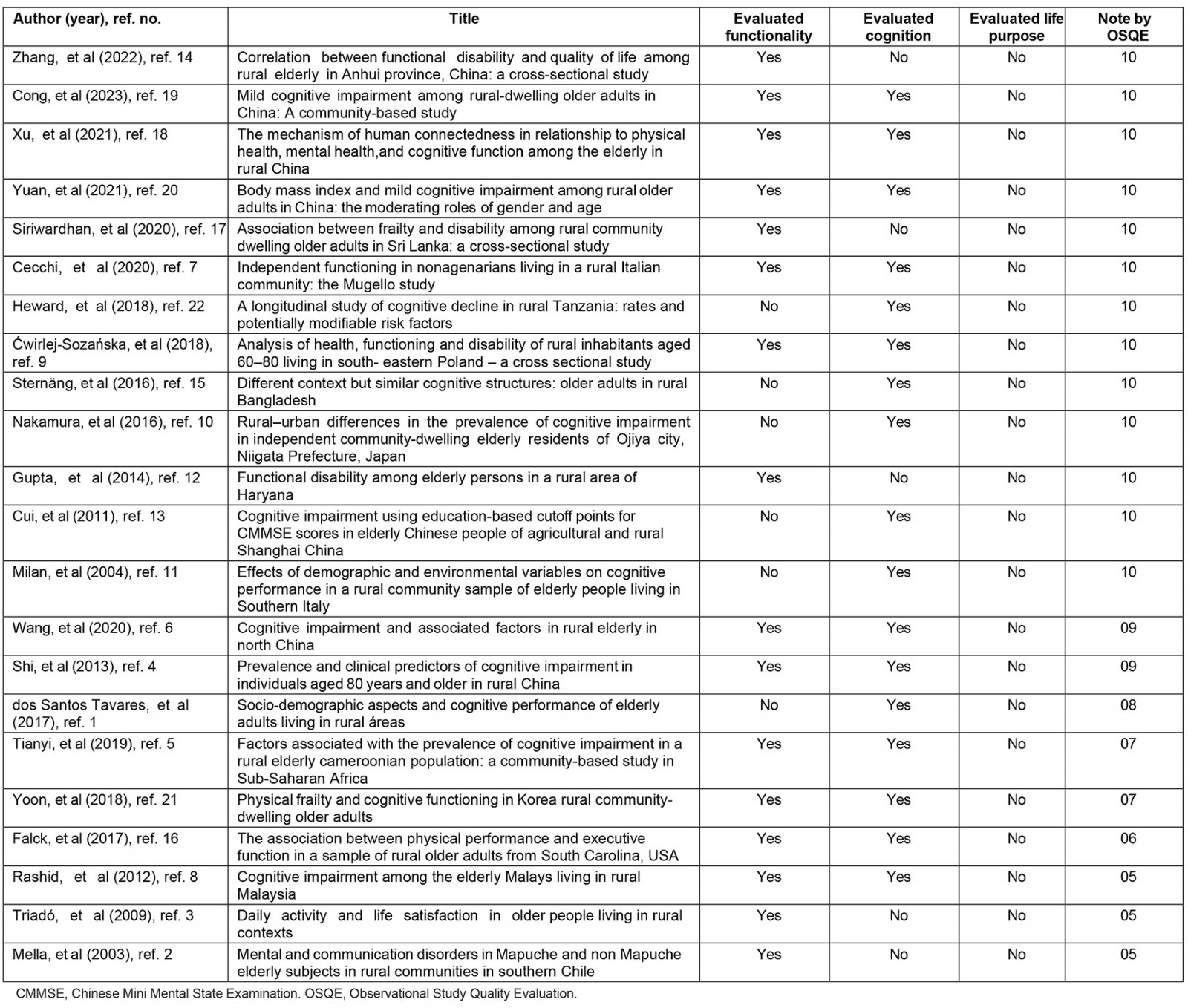

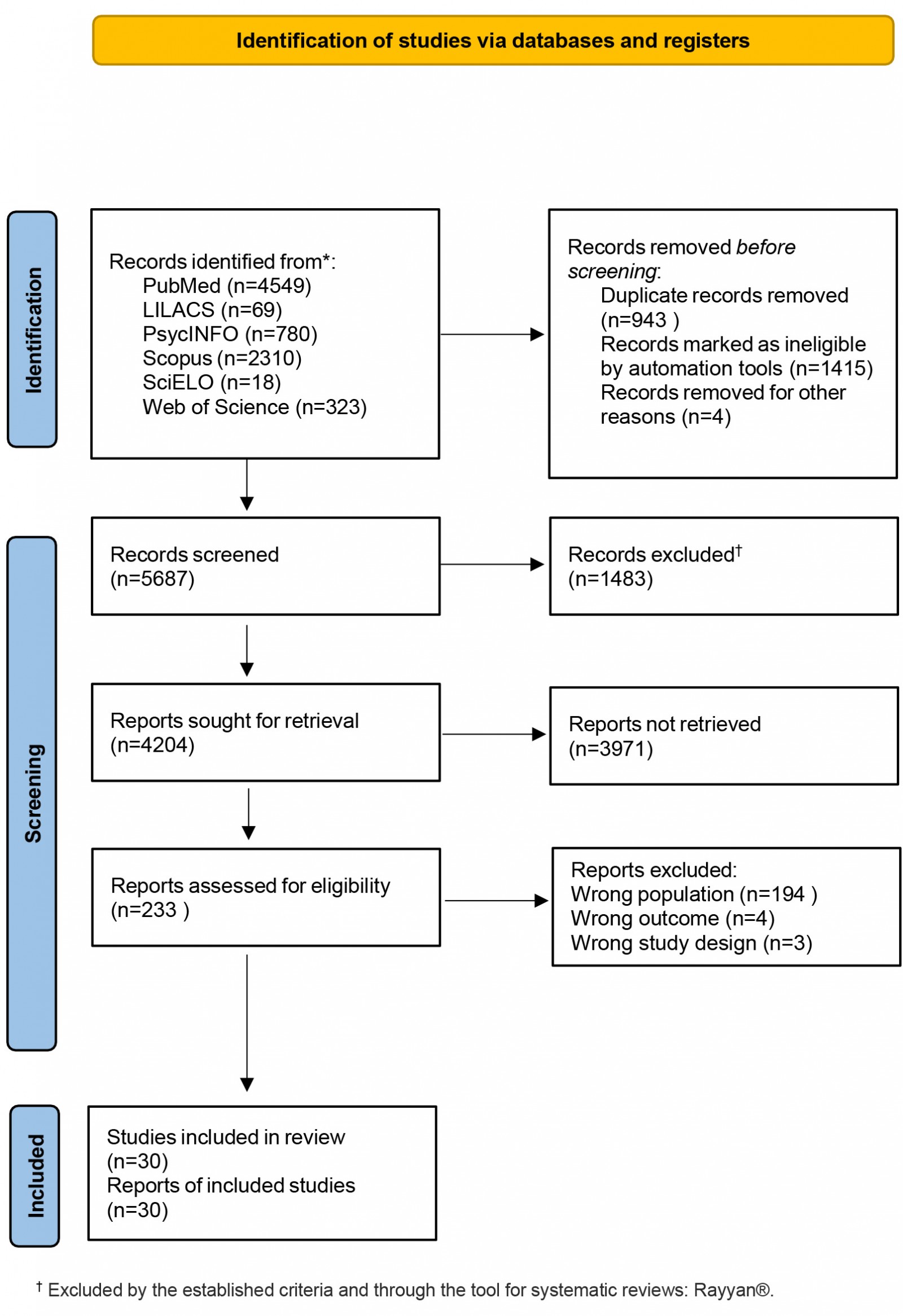

Of the 4204 articles identified in the database search, 3972 studies were excluded; 232 studies were read in full. In total, 30 articles were included in this review. Further information on the selection is shown in Figure 1. A total of 30 articles that were selected are organized by year of publication in Table 1. Of the 30 articles analyzed, 22 obtained a score of 5 or more after analysis by the OSQE. The majority (13) received a score of 10, two studies received a score of 9, one study received a score of 8, two studies received a score of 7, one study received a score of 6 and three studies received a score of 5. The articles with their respective scores from highest to lowest are described in Table 2.

Table 1: Studies included on cognition, functionality, and life purpose in rural elderly that comprise the study1-25,31-35

|

Author (year), ref. no. |

Sex |

Age (years), |

Population |

Country |

Type of study |

Sample |

Functionality |

Cognition |

Life purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Min Zhang, et al (2022), ref. 14 |

M and F |

60–69,

70–79,

≥80, |

Rural elderly in Anhui province |

China |

Cross-sectional |

3336 |

WHODAS2.0 Limitation in the mobility dimension (AOR=2.243, 95%CI 1.743–2.885), living together (AOR=1.615, 95%CI 1.173–2.226), activities of life (AOR=2.494, 95%CI1.928–3.226) and social participation (AOR=2.218, 95%CI 1.656–2.971) had a worse quality of life |

The cognitive domain was used through the WHODAS 2.0 Cognition (AOR=0.477, 95%CI 0.372–0.613) is a protective factor for quality of life |

Not rated |

|

Cong, et al (2023), ref. 19 |

M and F |

70.17±5.3 |

Baseline participants in the project Multimodal Interventions to Delay Dementia and Disability in Rural China (MIND-China), which is part of the Finnish Worldwide Network of Geriatric Interventions to Prevent Disability and Cognitive Impairment |

China |

Cross-sectional |

5068 |

Chinese version of ADLs: It did not show results or prevalence |

Clinical Dementia Rating Scale

The crude prevalence was 26.48% of mild cognitive impairment |

Not rated |

|

Xu, et al (2021), ref. 18 |

M and F |

60–69, >70, 192 (39.75) Missing data 13 (2.69) |

Dongliao County, Liaoyuan City, Jilin Province in north-eastern China |

China |

Cross-sectional |

483 |

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support No prevalence/results |

Short Portable Mental Status 85.9% (411) with 2 errors in cognitive tests. 85.92% (415) 0–15 in depressive symptoms |

Not rated |

|

Yuan, et al (2021), ref. 20 |

M and F |

70.14±6.17 |

Older people derived from the 2019 Rural Family Health Service Survey |

China |

Cross-sectional |

601 |

International Physical Activity Questionnaire: Only 562 (17.33%) had a low level of physical activity ADL: 2849 (87.88%) have normal ADLs IADL: Did not show prevalence |

Chinese version of the 30-item MMSE 18.5% had cognitive impairment |

Not rated |

|

Siriwardhan, et al (2020), ref. 17 |

M and F |

68 (64–75) |

Elderly people living in rural communities in the Kegalle district of Sri Lanka |

Asia |

Cross-sectional |

746 |

IADL and BADL The prevalence of ≥1 IADL limitations was high, at 84.4% among frail adults 38.7% of frail adults reported ≥1 limitations in BADLs. More than half of the frail elderly (58.3%) reported ≥1 physical and cognitive limitations in IADLs |

Not rated |

Not rated |

|

Wang, et al (2020), ref. 6 |

M and F |

73 (65–92) |

Structured face-to-face interviews were conducted to collect data in 10 communities in rural northern China |

China |

Cross-sectional |

1250 |

ADL Scale ADL dependence was strongly associated with cognitive impairment (OR 3.737, 95%CI 2.320–6.020), followed by poor vision and hearing. Positive coping was associated with a lower rate of cognitive impairment (OR 0.597, 95%CI 0.412–0.866) |

MMSE The positive rate of cognitive impairment among rural Chinese elderly aged 65 years and over was 42.9% (95%CI 40.1–45.6) Normal cognition: 57.1% (714). Impaired cognition: 42.9% (526) |

Not rated |

|

Tianyi, et al (2019), ref. 5 |

M and F |

80–84 (23.5) 85–90 (29.1) ≥90 (40) |

Elderly people living in 56 villages in Ji County |

China |

Cross-sectional |

723 |

ADL Scale No prevalence |

Chinese MMSE: 25.7% (163) have dementia Clinical Assessment of Dementia: 47.4% (297) present cognitive alterations |

Not rated |

|

Cecchi, et al (2020), ref. 7 |

M and F |

≥90 (median 92) |

Functionally independent nonagenarians from an Italian population living in a rural community |

Italy |

Cross-sectional |

475 |

Functional Independence Measure 457 participants; 68 of them (14.9%) were classified as independent, while the remaining 389 (85.1%) had a disability (i.e. needed help) in at least one IADL or BADL People classified as independent had a better perception of their state of health and a better physical and cognitive state than those in the non- independent group |

MMSE Did not show prevalence |

Not rated |

|

Heward, et al (2018), ref. 22 |

M and F |

76.2±8.414 |

Rural northern Tanzania |

Tanzania |

Cross-sectional |

327 |

Not rated |

IDEA cognitive screen 6.7% scored below the cut-off point of ≤7 on the IDEA cognitive screen at the beginning of the study and therefore screened positive for probable cognitive impairment, of which 13 (59.0%) still scored ≤7 at follow-up |

Not rated |

|

Cwirlej-Sozanska, et al (2018), ref. 9 |

M and F |

60–65,

66–70,

71–75,

76–80, |

South-eastern Poland (Podkarpacie region). Group chosen from a randomly selected and surveyed population of 1800 people, and the data obtained from the database of the Polish Ministry of Internal Affairs and Administration |

Poland |

Cross-sectional |

973 |

WHODAS 2.0 The highest average level of disability in the study group was found in ADLs (mean 28.94, SD 30.04), participation in daily living (mean 28.40, SD 23.29) and mobility (mean 26.04, SD 27.57) |

Used the cognitive domain through WHODAS 2.0 Mean 18.46, 95%CI 17.11–19.82 |

Not rated |

|

Yoon, et al (2018), ref. 21 |

M and F |

73.5±5.43 |

Koreans living in rural areas in 5 of the 11 communities in Sunchang Country, Jeonbuk province, Korea, 282 km south of Seoul |

Korea |

Cross-sectional |

104 |

SPPB Did not present the data and prevalence – only made an association SPPB was significantly associated with processing speed (p=0.049), working memory (p =0.000) and memory (p=0.004), while gait speed was significantly associated with processing speed (p=0.001), cognitive flexibility (p=0.027), working memory (p=0.000) and memory (p=0.002) |

MMSE Global cognitive functioning – average (mean 23.5 (SD 2.43)) MMSE <23: 64% (66)

Average memory:

Average processing speed:

Average cognitive flexibility:

Average working memory: |

Not rated |

|

Falck, et al (2017), ref. 16 |

M and F |

74.22±8.02 |

Seniors recruited from senior centers associated with the Lexington County Recreation and Aging in rural South Carolina |

EUA |

Cross-sectional |

56 |

Timed Up-And-Go Direct correlations without showing prevalence |

Trail Making Test Direct correlations without showing prevalence |

Not rated |

|

dos Santos Tavares, et al (2017), ref. 1 |

M and F |

60–70 (41) 70–80 (33.3) ≥80 (25.7) |

Elderly people registered with the Municipal Health Strategy |

Brazil |

Cross-sectional |

955 |

Not rated |

MMSE 11% (105) with cognitive decline |

Not rated |

|

Sternäng, et al (2016), ref. 15 |

M and F |

69.3±6.8 |

Participants lived in Matlab, a rural area in Bangladesh, about 60 km south-east of the capital, Dhaka |

Asia |

Cross-sectional |

452 |

Not rated |

Verbal fluency test Presented associations without showing the prevalence |

Not rated |

|

Nakamura, et al (2016), ref. 10 |

M and F |

75.7±7.0 |

A rural area and two urban areas in the city of Ojiya, Japan |

Japan |

Cross-sectional |

537 |

Not rated |

Revised Hasegawa Dementia Scale The prevalence of cognitive impairment was 20/239 (8.4%) in rural areas. Rural areas had a significantly higher prevalence of cognitive impairment (OR adjusted for age and sex = 4.04, 95%CI 1.54–10.62) than urban areas |

Not rated |

|

Confortin, et al (2016), ref. 31 |

F |

73.2±8.8 |

Rural area of Antônio Carlos, state of Santa Catarina, southern Brazil |

Brazil |

Cross-sectional |

270 |

Stand-up test Inadequate lower limb strength was observed in 29.8% (95%CI 23.9–35.6%) of women |

MMSE

Normal:227 (85.3%) |

Not rated |

|

Nadel, et al (2014), ref. 23 |

M and F |

76.8±8.1 |

Person over the age of 60 years residing in the rural area of the study |

Costa Rica |

Cross-sectional |

90 |

Not rated |

MMSE 48.3% with cognitive impairment |

Not rated |

|

Gupta, et al (2014), ref. 12 |

M and F |

67.8±7.41 |

Ballabgarh Rural Area, Faridabad District, Haryana, which is the institute's rural practice area. There are 28 villages under this intense rural practice area. These villages are almost 50 km from Delhi and represent a typical rural community of Haryana |

India |

Cross-sectional |

836 |

ADL The prevalence of functional disability was estimated at 37.4% (95%CI 34.2–40.7). Prevalence was lower among men (35.9%) than among women (38.8%). Prevalence increased with age, from 23.7% in the youngest age group of 60–64 years to 63.8% in the oldest age group of >75 years |

Not rated |

Not rated |

|

Shi, et al (2013), |

M and F |

83.51±3.42 |

Elderly people aged 80 years and over from 56 villages in rural China visited in their homes |

China |

Cross-sectional |

723 |

ADL Did not show the prevalence |

Chinese MMSE Dementia Rating Scale The prevalence of cognitive impairment among individuals aged 80 years and over was 73.2% (47.4% for cognitive impairment without dementia and 25.7% for dementia) |

Not rated |

|

Rashid, et al (2012), ref. 8 |

M and F |

60–70,

71–80,

>80, |

Twenty-two villages in a north-western Malaysian state called Kedah, which has one of the highest elderly populations in the country. All the villagers were Malay Muslims and most of them worked as fishermen and farmers due to the village's proximity to the sea and the foot of a mountain |

Ásia |

Cross-sectional |

418 |

Barthel index

Dependent: 14 (3.3%) |

Elderly Cognitive Assessment Questionnaire The prevalence of cognitive impairment among the elderly in these villages was 11% (n=46) There was an increase in the prevalence of cognitive impairment with increasing age (p<0.05) Being single (OR 2.31), unemployed (OR 2.74) and living alone (OR 2.32) were significantly associated with the risk of cognitive impairment |

Not rated |

|

Cui, et al (2011), |

M and F |

70.6±6.6 |

A community of two towns (Huaxin and Xujing) in the Qingpu district, located in the western suburbs of Shanghai Face-to-face interviews were conducted to collect relevant information with questionnaires |

China |

Cross-sectional |

2809 |

Not rated |

Chinese MMSE The prevalence of heart failure was 35.6% (95%CI 33.8–37.4) for both sexes when the cut-off point of 23%u204424 was used However, when the cut-off point was changed in relation to the different levels of education, the prevalence of cognitive impairment was 7.0% The total MMSE score mean 24.4±4.2 (range 5–30) |

Not rated |

|

de Vasconcelos Torres, |

M and F |

74.47±9.42 |

Randomly selected by lottery at the health centers in the region. 10% of households with elderly people in each of the four health units were included |

Brasil |

Cross-sectional |

150 |

Barthel index 78% (117) were dependent for BADLs and 22% (33) were independent 65% (98) were dependent for IADLs, 34% (52) were independent |

MMSE Used as an inclusion criterion above 23 points without presenting prevalence |

Not rated |

|

Rigo, et al (2010), ref. 24 |

M and F |

69.8±7.2 |

Household surveys were carried out with the aid of a map of the region and visited the 35 homes in the community's catchment area |

Brazil |

Cross-sectional |

33 |

Older American Resources and Services 35.3% of the elderly were independent, 52.9% were mildly dependent |

MMSE Overall test average 25.8 (2.8) |

Not rated |

|

Triadó, et al (2009), ref. 3 |

M and F |

736±6.12 |

Seven cities in the interior of Catalonia and five towns in the Community of Valencia. All the towns visited had fewer than 1000 inhabitants and their way of life was based on agriculture |

Spain |

Cross-sectional |

216 |

ADL Did not present the final score of the questionnaire – they only mention the performance of the activities and do not present the prevalence |

Not rated |

Not rated |

|

Morais, et al (2009), ref. 32 |

M and F |

80–84 (58.3) 85-89 (30.7) 90–94 (9.5) 95–100 (1.5) |

Long-lived elderly people in rural areas of Rio Grande do Sul |

Brazil |

Cross-sectional |

137 |

Not rated |

MMSE: MMSE mean above the cut-off point for determining cognitive impairment (mean 20.05, SD 6.67) Brazilian Portuguese version of Depressive Cognition Scale: The differences between males and females regarding depressive symptoms were not significant. |

Not rated |

|

Poderico, et al (2006), ref. 33 |

M and F |

71.8±6.7 |

Elderly people in a rural community in Italy |

Italy |

Cross-sectional |

121 |

Katz Index of ADL Did not present prevalence or test results, only association |

MMSE Did not show prevalence or test results, only association |

Not rated |

|

Milan, et al (2004), ref. 11 |

M and F |

70.1±6.43 |

Population register of a rural community in southern Italy (San Marcellino, province of Caserta) |

Italy |

Cross-sectional |

226 |

Not rated |

MMSE The average MMSE score for the entire population was 22.013 (SD 4.70) No schooling: 28.3% (64). 1–5 years of schooling: 58.4% (132). 6–10 years of schooling: 9.3% (21). More than 10 years of schooling: 4% (9) |

Not rated |

|

Mella, et al (2003), ref. 2 |

M and F |

71±7 – 74±8 |

Elderly people from a rural Mapuche community and a non-Mapuche community. The subjects were interviewed in their homes |

Chile |

Cross-sectional |

100 |

Functional Autonomy Measurement System 70% (70) were independent in their mental functions 26% (26) had mild dependence 57% (57) were independent in communication 39% (39) had mild dependence |

Not rated |

Not rated |

|

Worral, et al (1994), ref. 34 |

M and F |

79.9±6.1 |

Seniors at a health center in a rural community in Canada |

Canada |

Cross-sectional |

167 |

Not rated |

Canadian Mental Status Questionnaire 49 people (13.0%, 95%CI 9.6% and 16.4%) scored either severely or moderately cognitively impaired |

Not rated |

|

Park and Ha (1988), ref. 35 |

M and F |

For men:

65–69 (55) For women:

65–69 (22) |

Rural community in Korea |

Korea |

Cross-sectional |

549 |

Not rated |

MMSE The prevalence rates of cognitive impairment were significantly higher in elderly women (64%) than in elderly men (33%). Sex differences in the prevalence of both mild (25% in men versus 45% in women) and severe (8% in men versus 19% in women) impairment reached statistically significant levels |

Not rated |

Table 2: Articles included with Observational Study Quality Evaluation score1-22

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

Discussion

Growing old in the world's rural context is still a challenge, yet there is still disagreement in the literature about the positive and negative effects of growing old in the rural context. In general, rural aging is predominantly female, with low schooling and some cognitive and functional changes that need to be better investigated. The findings of this study show that people age in a particular and individualized way in developed and developing countries.

This systematic review identified and presented an evaluation of cross-sectional studies conducted with the rural elderly population around the world from the perspective of physical functionality/function, cognition and life purpose. For each study, when found, the test carried out, its result and the study's quality assessment score were indicated. The selected articles describe how aging in a rural context from a cognitive, functional and physical function perspective is still very heterogeneous, diverse and highly dependent on the rural region in the world where this aging occurs1-22.

It was observed that in the rural context people age very differently in developed and developing countries, with positive or negative aspects depending on the outcome studied within this population.

Studies carried out on the Asian continent4,6,10,12-15,17-20, Europe7,9,11 and Africa22 were those with the highest scores on the methodological quality scale and low risk of bias. Only one study carried out in Latin America scored 81. The most mentioned outcome in this systematic review was cognition1,4-10,14,16-22, followed by functionality and physical function2-9,12,14,16-21. None of the articles in the systematic review assessed the purpose of life in elderly people aging in a rural context. The most widely used instrument for assessing cognition was the Mini-Mental State Examination, with several versions adapted and adjusted to the reality of each country1,4-7,11,13,20,21. The most commonly used functional assessment tools were those that assessed the basic and instrumental activities of daily living of the elderly in a rural context3-7,12,17,20.

Rural aging in the world is predominantly female aging1-17,19-22 complex and closely linked to schooling, financial income and the various roles these women play in their communities and at home.

When it comes to assessing cognitive impairment, there are still divergences and different results when looking at elderly people aging in a rural context. Cong et al (2023)19 studied a population of 5068 elderly farmers and found that cognitive impairment was greater in elderly farmers and illiterate women. Compared to men, women were less educated, more likely to be farmers and had lower scores in the domains of language, attention and executive function, and a higher score on the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) (p<0.01)19.

In general, several studies have shown that older women in rural areas with low levels of education have a higher cognitive risk4-6,13,17,18.

For Yuan et al (2021)20, BMI and weight in addition to the moderating roles of age and gender need to be considered when looking at elderly people aging in a rural context, since gender and age moderated the association between BMI and cognitive changes among rural Chinese elderly people. Older women with a low BMI were more likely to have cognitive disorders. Older men with a high BMI were also found to be more likely to develop cognitive problems20.

Tianyi et al (2019) also adds the prevalence of cognitive problems in single elderly women with higher systolic blood pressure who age in rural communities5. Having no formal education, low grip strength at the start of the study, being female and having depression at follow-up were independently associated with cognitive decline in elderly people aging in a rural context5.

In contrast, a Brazilian study found no association between gender and cognitive decline1, although it was associated with older age, low levels of education and widowhood. In the same study, when assessing cognition and attention, the ability of elderly people to calculate, visual and constructive ability and recall memory were the most negatively impacted. Rashid et al also highlights the prevalence of cognitive problems among older people who are single, unemployed and live alone8. Milan et al (2004) pointed out that rural elderly people who lived with their families scored better on the cognitive assessment than those who lived alone or only with their spouses11.

However, Wang et al (2020) found no significant differences in cognitive impairment by age or sex before the age of 75 years6. Older age, lack of formal school education, dependence on basic subsistence allowance as the sole source of income, poor hearing and visual function, diabetes and dependence on activities of daily living were associated with a higher rate of cognitive impairment, while tea consumption and hepatic steatosis were associated with a lower rate of cognitive impairment.

In the study of Cwirlej-Sozanska et al (2018) differences by gender were also not found9: both among elderly men and women aging in a rural context the level of disability increased with age, and statistically significant differences were observed between men and women in all pairs of age groups considered, except those in the age groups of 60–65 and 66–70 years. In each age category in the female group, there was a higher average level of disability than in the male group; however, significant differences were only observed in the 71–75-year age group (p=0.009).

Sternäng et al (2016) points out that older women were worse in all the cognitive skills performed15. However, the model showed strong (or scalar) invariance for age and partial strong invariance for gender and literacy. Semantic knowledge and processing speed showed weak (or metric) gender invariance, and semantic knowledge also showed sensitivity to illiteracy. It is also noteworthy in this study that literacy was, in general, a strong predictor of cognitive performance. It is worth noting that the cognitive differences between the sexes in Bangladesh differed from those normally found in Western samples. Women generally performed worse in all the cognitive skills assessed, with the smallest differences between the sexes found in recall, recognition and verbal fluency15.

Being female and having a history of stroke increased the risk of cognitive impairment4. For Mella et al (2003)2 in the cognitive assessment of rural elderly people, visual function was the most impaired among the communication items in the two groups studied.

The study of Nakamura et al (2016) is noteworthy because it compared elderly people aging in rural and urban settings and concluded that there is a prevalence of cognitive impairment in Japanese elderly people aging in rural settings10, although the prevalence of cognitive impairment tended to be higher in men than in women. This observation is inconsistent with the notion that the prevalence of dementia is higher among women in studies conducted in Japan.

There is still a health disparity in the gender comparison with elderly women at a disadvantage when compared to elderly men. Specific attention needs to be given to the most disadvantaged elderly female population. It is worth mentioning that elderly women have a longer life expectancy than men and that health services and long-term care should be considered for them18.

The studies that made up this systematic review also described the activities of daily living and instrumental activities of elderly people aging in rural areas around the world. In a study of 457 nonagenarians in a rural region of Italy, 68 of them (14.9%) were classified as independent, while the remaining 389 (85.1%) had a disability (i.e. needed help) in at least one instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) or basic activity of daily living (BADL)7. The independent group was represented by an equal share of men and women (while the non-independent group was 68% women), who were better educated, slightly younger and reported less help from someone than their non-independent peers; the elderly classified as independent had a better perception of their state of health and a better physical and cognitive state than those belonging to the non-independent group7.

The study by Zhang et al (2022) pointed out that mobility is the most important outcome and is directly related to the quality of life of elderly people aging in a rural context14, along with social participation, activities of daily living, number of chronic diseases and the elderly person's professional situation. Another study that investigated this same outcome (physical performance and cognitive function) showed that in the rural environment mobility can be associated with various executive function processes and that improving and maintaining physical abilities and mobility can positively affect cognitive ability16. Siriwardhana et al (2020) in a study with a high response rate (99.5%) mentioned that assessing the functional capacity of the elderly in a rural context is important17, with the prevalence of ≥1 IADL limitations being high, 84.4% among the frail elderly. A total of 38.7% of these frail elderly reported ≥1 BADL limitations. More than half of the frail elderly (58.3%) reported ≥1 physical and cognitive limitations in IADLs. It was found that being frail decreased the chances of not having limitations in the IADLs and was associated with a higher count of limitations in the IADLs. Disability was also an outcome in the study9 where the highest average level of disability in the rural elderly group was found in activities of daily living (mean=28.94; standard deviation (SD)=30.04), participation in daily life (mean=28.40; SD=23.29) and mobility (mean=26.04; SD=27.57).

Frailty associated with cognition and physical function was investigated in rural elderly people in the study of Yoon et al (2018); a significant association was found between frailty and cognitive function when assessing processing speed, cognitive flexibility, working memory and memory 21. The synchronicity of frailty and cognitive dysfunction may be the basis of the negative health effects associated with aging, although causal relationships between physical frailty and cognitive impairment are still unclear in the literature21.

It can be seen that functional incapacity is something that is part of the routine for elderly people who age in a rural context12. Prevalence was lower in men (35.9%) than in women (38.8%). It increased with age and was more common among older people who were not currently married, had diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease12. Triadó et al (2009) described that, regardless of gender, leisure activities and working time play an important role in the way this group ages3. However, women spent more time on instrumental activities and less time on leisure. Overall, the differences between instrumental and general activities were not related to life satisfaction.

Although life purpose is an important outcome for successful aging, it is not yet present in research with rural elderly people around the world. A possible limitation of this study may be the use of the OSQE scale given its interpretations, although it is commonly used and cited for assessing risk of bias and methodological quality.

Strengths and limitations

This study presents worldwide epidemiological data on how to age in a rural context from the perspective of cognition, physical functioning and life purpose.

It is the first systematic review involving the theme of life purpose worldwide in rural elderly people.

It is a systematic review of cross-sectional studies that, although it cannot describe clinical outcomes, presents sociodemographic data and data on cognition, physical functioning and life purpose that can help in making public health decisions for this population.

The definition of the search terms for this systematic review, as well as the search for articles and the cross-referencing of search terms, were carried out by a trained librarian who carried out an exhaustive search of the databases with all the possible variations, so it is highly unlikely that any study was left out of the sample studied.

Conclusion

This systematic review showed that rural aging in the world is predominantly female and happens differently depending on the rural context in which the elderly age. In cross-sectional studies with this population, the most commonly used test for cognitive assessment is the Mini-Mental State Examination in its various validations. There are numerous functional tests focusing on activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living that have a direct impact on the physical function of these elderly people. Life purpose has not yet been investigated in the rural population and its use is important since elderly people who have a good life purpose age positively from a cognitive and functional point of view. Although there have been good cross-sectional studies carried out with the rural elderly population, they are still not enough due to the plurality of aging in this context. Developing countries need to better investigate how their rural elderly age, which can have a direct impact on the formulation of public health and good aging policies for this group. There is a need for more epidemiological studies that describe how people age in rural areas, following strict methodological guidelines.

Public health policies for the rural population can only emerge after the way this group ages is known and described in the literature.

Funding

The principal author of this study received a doctoral scholarship from the Amazonas State Research Support Foundation – Brazil.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this study.