Introduction

Rural nursing is defined as the provision of health care by nurses to people living in sparsely populated areas1. The dimension of doing in rural nursing represents a practice committed to solving problems in each of the diverse contexts, with the construction of different forms of care, and with the exercise of critically reflecting on the actions carried out2. The rural nurse has skills beyond general clinical practice, which include the ability to act in defense of the community, understand local culture, offer intentional support, educate the community, and even provide advance care planning, in addition to palliative care2,3.

In rural settings, the concept of health often varies depending on the local context. It is commonly perceived as the ability to perform everyday tasks. As a result, many healthcare needs may not be adequately addressed by nursing models designed for urban populations, highlighting the need for health professionals to adapt their approaches accordingly2. Furthermore, rural nurses face several obstacles that generate suffering during their work process. The rural context is marked by long distances between the health unit and the population, lack of public transport, precarious infrastructure, access difficulties during rainy periods, work overload, and inadequate remuneration, with professionals often assuming the role of ‘does everything’ (similar to a ‘jack of all trades’ but implying taking on tasks beyond their formal responsibilities). In addition, fragmented teams and the absence of other health professionals hinder shared care and even lead some professionals to abandon rural practice4-9.

In addition to the previous factors, the lack of training during undergraduate and postgraduate courses in rural nursing nationally and internationally contribute to breaking the cycle of invisibility of the rural population. Therefore, it is urgent that educational programs incorporate rural nursing into their pedagogical and political frameworks. Doing so would promote professional autonomy and prepare nurses to develop and adapt knowledge and practices that are responsive to the unique demands and specific needs of rural healthcare settings2,10. Training in rural nursing in undergraduate education is a need felt by rural nurses11.

Despite these factors, studies indicate that rural nurses implement their practice with pleasure and satisfaction in various situations10,12 and are able to develop characteristics such as closer ties and belonging to the community, recognition by the community, production of holistic and culturally competent care, space for growth and learning with the work process, among other factors12-15.

The nursing work process is understood as something complex and multifaceted that requires articulation between skills, knowledge, and attitudes. Its objective is to transform nature with specificity that characterizes specific fields of action, ways of political insertion, and social contribution to which nursing professionals need to proceed consciously. There are five work processes in nursing according to the adopted framework16: caring (or assisting), managing (or administering), teaching, researching, and politically participating in nursing.

The analysis of the nurse's work process and its conditions and characteristics of insertion in the health work process makes it possible to understand with greater lucidity what the intent of nursing intervention has been, be it related to an individual, a family or a community17.

From this perspective, the duality between pleasure and suffering in the rural nurse's work process finds meaning in the insights of Christophe Dejours18. For Dejour, pleasure and suffering at work are linked to the concept of zeal, which is an inventive intelligence, generating solutions and capable of being mobilized in often challenging work situations, related to conflicts that occur between workers around the workplace. It is a way of treating the distance between what is effective and what is prescribed, aiming to eliminate the distance between them. Suffering at work begins when, despite their zeal, a worker is unable to complete a task. Pleasure, on the contrary, begins when, thanks to their zeal, a worker manages to invent convenient solutions. Pleasure and suffering at work are not a supplement to the soul; they are strictly inseparable from work18.

This study aims to identify and map the factors that cause pleasure and suffering in the rural nurse's work process. Its relevance lies in the possibility of revealing factors experienced in daily work that can be reinforced to enhance care, as taking care of the caregiver will lead to better care; or discontinued through interventions aimed at mitigating the biopsychosocial factors that cause suffering.

The motivation behind this study stems from the persistent invisibility of rural nurses in health policy, research, and training curricula, despite their critical roles in underserved areas. These professionals face unique challenges, such as geographic isolation, lack of resources, and insufficient educational preparation, which contribute to high levels of stress and professional dissatisfaction. The magnitude of this issue is global, as rural health systems struggle with recruitment, retention, and the mental wellbeing of nurses. The impact is not only on individual health professionals but also on the quality of care delivered to rural populations. A scoping review is necessary to comprehensively map the existing literature, identify knowledge gaps, and inform future interventions and research directions aimed at supporting rural nurses.

Method

This scoping review was prepared according to the recommendations of the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR), based on the theoretical framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley19. The study protocol was registered via Open Science Framework.

The study in question, with an exploratory nature, aims to identify in the literature relevant studies that mention the aspects that cause pleasure and/or suffering in the rural nurse's work process, under the framework of Christophe Dejours' psychodynamics of work. The operationalization took place in five stages, the first being the identification of the guiding question, which emerged from ‘patient, concept, context’ (PCC): In the work of rural nurses (P), which factors in the work process cause pleasure and suffering (C) within the scope of rural health services (C)?

The second stage consisted of identifying relevant studies to answer the previous question. To this end, controlled terms were selected from the Health Sciences Descriptors and Medical Heading Subjects, in addition to the selection of some keywords. The third stage corresponded to the selection of studies in the literature, using the following databases: PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, EMBASE, Web of Science, PsycInfo, and LILACS. The gray literature was consulted in the following resources: Portal of Theses and Dissertations from CAPES, Theses Canada, National EDT and Google Scholar.

The selection involved the use of the following combination in Portuguese and English, when applicable: (nurses) OR (nurses and nurses) OR (nursing team) AND (work flow OR work process OR pleasure OR suffering) AND (rural nursing OR rural health services). Data collection was carried out in November and December 2022 and updated in February 2024.

Before moving on to the next stage, the results were refined based on the selection criteria, which included quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods studies from research articles, theses and dissertations that responded to the objective proposed by the review and were accessible for free in databases with access from the Federated Academic Community, via the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte. There was no time limit for the study, but editorials, opinion articles, theoretical essays and bibliographic reviews were adopted as exclusion criteria. Duplicate articles were excluded.

The penultimate stage, which concerns data analysis, was initially carried out by reading the titles of the studies obtained, then refined by reading the abstracts of those that remained after exclusion based on the title. The final sample was obtained from reading the full text of the studies that made up the review, which remained after excluding studies based on reading the summary and full text.

The final stage was reached through analysis of data collection indicators: database, country, year of publication, identified nurses' work processes according to Sanna's framework16, and factors that cause pleasure or suffering in this process of work, interpreted in light of Dejours’ psychodynamics of work.

Psychodynamics of work is a clinical discipline that is based on the knowledge and description of the relationship between work and mental health, as well as a theoretical discipline that strives to include the results of clinical research into the relationship with work in a theory of subject. For Dejours, the psychodynamics of work can contribute to the analysis of the relationships between work and subjectivity. The implications of this analysis are twofold: on the one hand, understanding the human consequences of the neoliberal turn; on the other, enriching the conception of action in the political field20.

Results

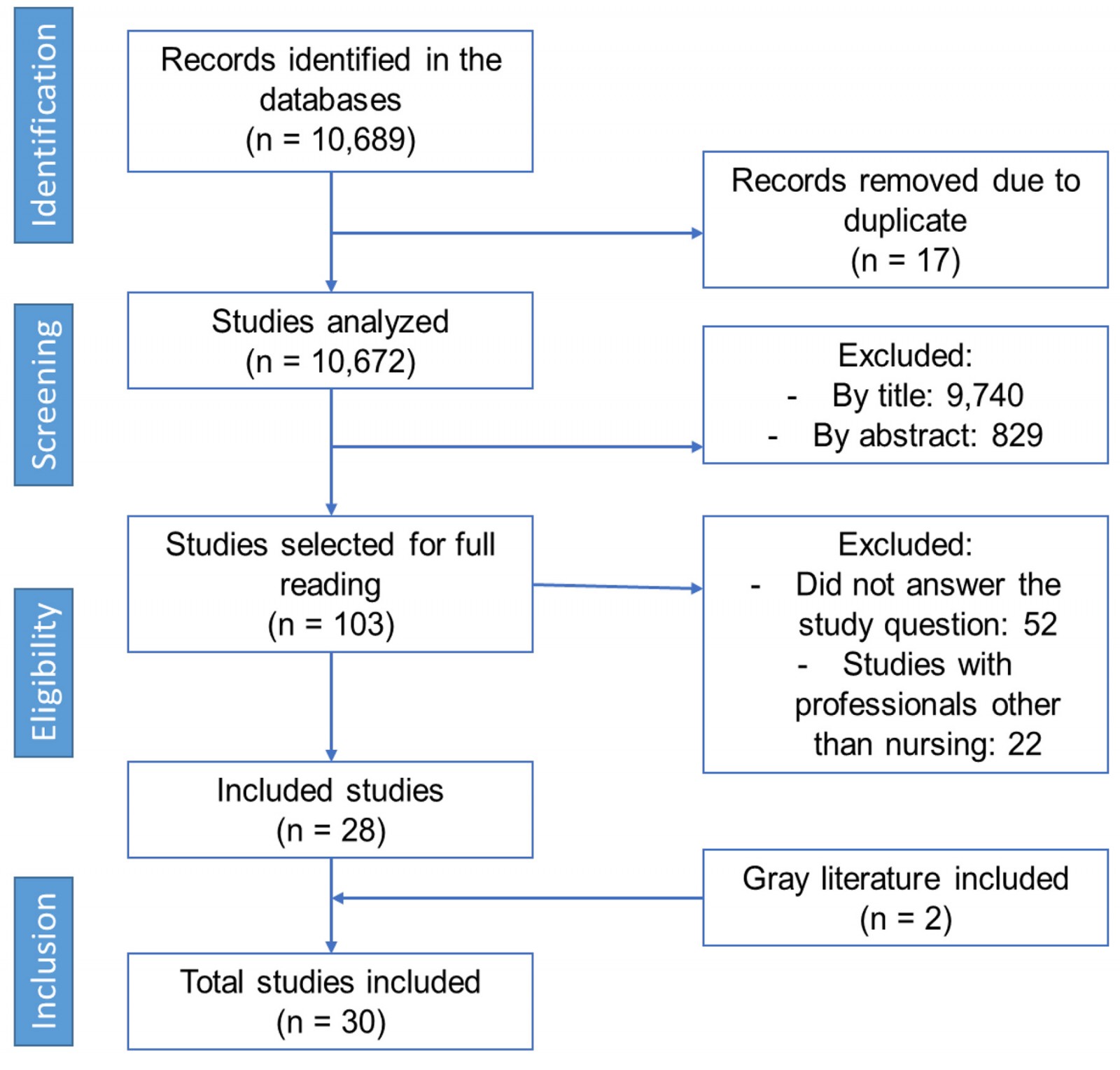

Around 10,689 records were identified in the databases, 0.001% (n=17) of these in duplicate. After evaluating the selection criteria, the final sample consisted of 30 studies, of which 96.66% (n=29) were scientific articles and 3.66% (n=1) doctoral theses, as represented in the flowchart in Figure 1.

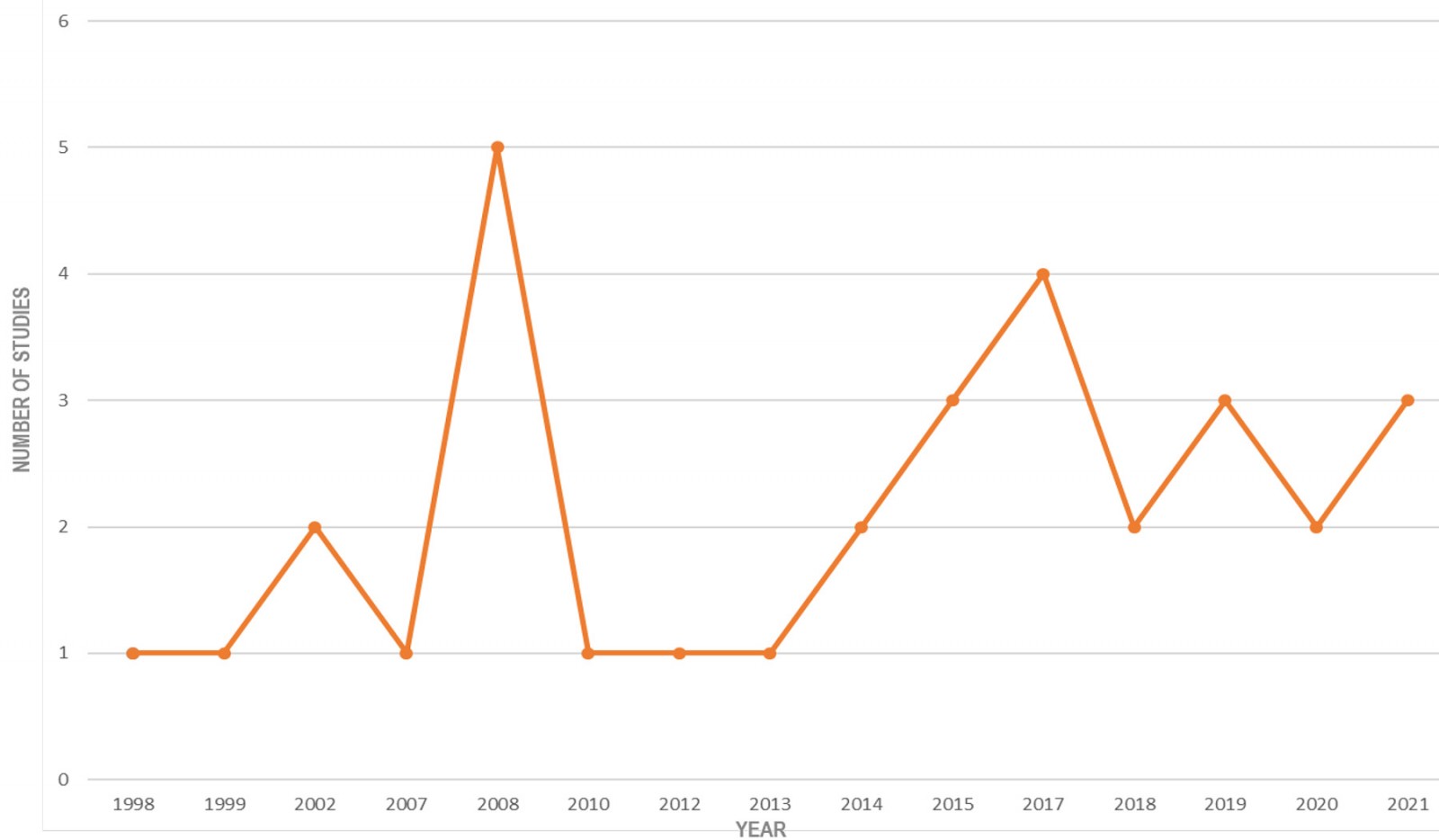

Regarding the year of publication of the included studies, the period between 2007 and 2008 stood out, with 16.67% of publications, as shown in Figure 2.

Regarding the sources of the studies, it is noteworthy that the majority were retrieved from EMBASE, representing 33.33% (n=10) of the studies; followed by PubMed, with 30.0% (n=9) studies; MEDLINE and CINAHL each represented 13.33% (n=4) of the studies; and 5% (n=2) of the studies came from Scopus. As for gray literature, the Theses Canada portal corresponded to 3.66% (n=1) of the studies.

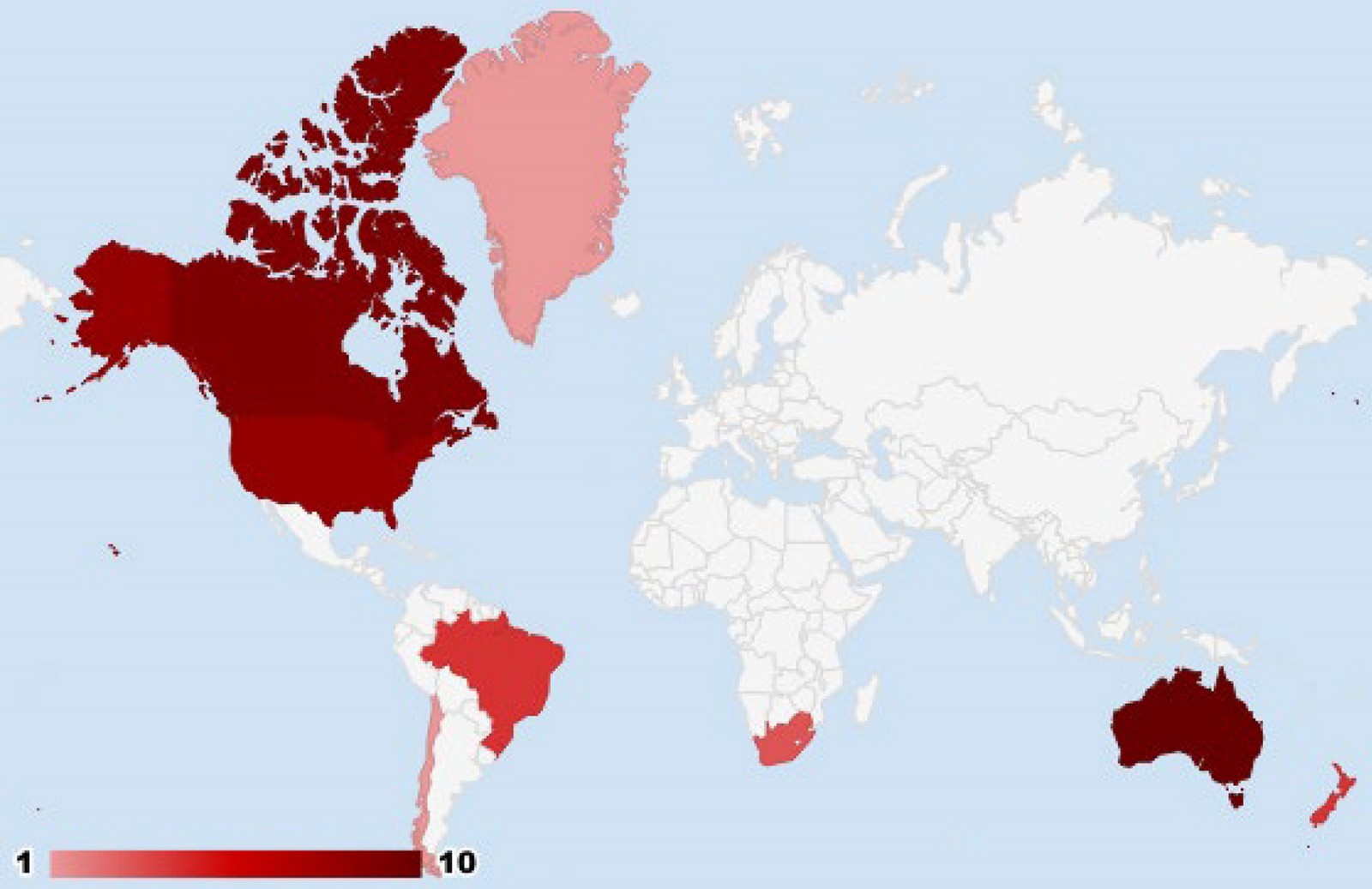

Regarding the countries where studies were published, there was the greatest number of publications were from Australia, with 33.33% (n=10) studies; followed by Canada, with 23.33% (n=7); and the US, with 20.0% (n=6) of studies (Fig3).

Regarding the work processes in nursing identified in the studies in light of Sanna's framework16, the work processes of caring in nursing, managing in nursing and teaching in nursing were identified. The factors related to pleasure and suffering in these rural nurses' work processes are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Factors related to pleasure and suffering in rural nurses' work processes

| Work process | Pleasure | Suffering |

|---|---|---|

| Caring in nursing | Holistic care13,21,22 | Low-resource/precarious environment6,9,11,21,23 |

| Belief that they provide quality care21 | Isolation (geographic and from other professionals)6,13,15,21,24-26 | |

| Care for the community21,27 | Distance from continuing education6,21 | |

| Feeling valued by the community11,12,14 | Lack of academic training in rural practice10,11,28 | |

| Interaction with the community beyond the service10 | Difficulties in dealing with the specificities of the population12 | |

| Job satisfaction9,11,12,29,30 | Work overload5,31 | |

| Bond with the community 10,12,25,28,32 | Perform non-nursing tasks10 | |

| Directly comprehensive care33 | Lack of professional and monetary recognition4 | |

| Cultural competence15 | ‘Handyman’ role8 | |

| Develop proficiency in more than one specialty34,35 | Difficulty organizing schedule10 | |

| Autonomy5,28,31,36 | Difficulties in dealing with the specificities of the population30 | |

| Ability to play multiple roles24 | ||

| Managing in nursing | Autonomy5,8,14,31,37 | Environment with few resources6,21 |

| Teaching in nursing | Space for growth and learning12 | Environment with few resources6 |

| Role of educator5 | Distance from continuing education6,21 |

Figure 1: PRISMA flowchart of study selection process included in scoping review.

Figure 1: PRISMA flowchart of study selection process included in scoping review.

Figure 2: Year of publication of studies included in scoping review.

Figure 2: Year of publication of studies included in scoping review.

Figure 3: Countries in which studies included in scoping review were conducted.

Figure 3: Countries in which studies included in scoping review were conducted.

Discussion

It is understood that it is not possible to conceive a work organization that, in some way, does not allow professionals to suffer. Pleasure–suffering results from the interrelationship between workers and the work context. Health and pleasure at work are processes that are constantly changing and must be achieved daily. Therefore, health at work results from the way in which the worker faces conflicting situations present in the context38.

For the rural nurse, living in the community continues after providing care, differing from what generally occurs with professionals who practice in urban settings or at hospital level39. International literature calls this ‘living my work’, since nurses indicate that they have this perception, and declare that their work goes far beyond the workload for which they were hired and are paid. It can cause the identified suffering factors such as overload, practicing the profession beyond the work shift, which can be reinforced by the shortage of professionals5.

Knowing all the factors predisposing to suffering and their possible repercussions on the health and illness of the professional leads to questioning whether workers remain in a state of normality in the face of all these risk factors. It is believed that this state of normality reflects an unstable balance between psychological suffering and the defense strategies and subjective mobilization used by professionals38.

Studies indicate that rural nurses implement their practice with pleasure and satisfaction12,29, and are able to develop characteristics such as closer ties and belonging to the community, as well as recognition from the community, production of holistic and culturally competent care, space for growth and learning with the work process, among other factors12,13,15,28.

In rural nursing, the professional needs to be flexible, assume additional responsibilities that are traditionally beyond their professional role, have a broad knowledge base, and implement an expanded scope of practices, applicable to a range of cultures, ages and pathophysiological conditions6. However, if not well balanced, these characteristics can cause suffering to professionals.

Therefore, the level of demand and psychological suffering experienced by nurses seems to generate harmful consequences for their mental health, not mitigated by the recognition of the contribution to the work organization, which could transform this suffering from pathogenic to creative, as proposed by Dejours40.

Work is a fundamental and ancient aspect of human life, deeply tied to individual subjectivity. It can be a source of both fulfillment and pleasure for some, and fatigue and suffering for others. In the daily practice of nursing, professionals often face exhausting and uninterrupted shifts, task overload, and precarious working conditions – whether due to limited human or material resources – all while constantly dealing with the pain and suffering of others41. In rural nursing, these challenges are even more complex, reflecting broader global struggles and setbacks faced by the nursing profession42,43.

Even though work can be a source of suffering, from another perspective it provides experiences of pleasure, as it is through this that humans build their lives and enter the world of work, not only as a form of survival, but also for personal and professional fulfillment. Therefore, work allows the process of training the individual, in their technical, aesthetic, cultural, political, and artistic productivity involving subjectivity44.

Pleasure and suffering are subjective experiences, which involve a being of flesh and a body in which it is expressed and experienced, in the same way as anguish, desire, and love. They are therefore experienced in ways that cannot be the same from one person to another45.

Suffering at work arises when, despite their dedication, workers are unable to complete their tasks. In contrast, pleasure emerges when commitment enables workers to find effective and creative solutions. Pleasure and suffering are not merely emotional by-products – they are inherently tied to the nature of work itself. Dedication in the workplace is inseparable from the emotional and subjective involvement of the worker, which constantly confronts reality – understood here as that which resists being fully controlled or mastered18.

Work should be a space for organizing social life, where workers are recognized as subjects who both influence and are influenced by it, despite the domination present in capitalist relations. Through work, a double transformation takes place: humans act on nature, modifying it, and at the same time the work develops its potential38.

From this perspective, rural nurses must develop coping strategies to address the factors that contribute to work-related suffering. They also need to critically reflect on their practice to identify interventions capable of overcoming the challenges that negatively impact their mental health45. At the same time, it is essential to strengthen the elements that bring satisfaction and fulfillment, aiming to maintain a healthy balance between pleasure and suffering at work and to foster a greater sense of professional wellbeing. Likewise, the management of health services must intervene together with professionals to further strengthen this balance.

This study highlights that while the challenges and complexities of rural nursing are globally recognized, their emotional and psychological consequences on nurses remain insufficiently addressed. Understanding the interplay between pleasure and suffering in rural nursing is crucial not only for recognizing the invisible labor of these professionals but also for creating supportive structures that mitigate harm and enhance wellbeing. For international readers, this review offers valuable insights into the global commonalities in rural nursing – particularly the emotional toll and rewards of working in remote settings. Although numerous factors influencing pleasure and suffering have already been identified, the next step involves transforming this knowledge into actionable strategies to improve rural nurses’ working conditions and mental health. Understanding these factors is critical because it highlights not just the logistical and structural challenges, but also the emotional and psychological dimensions of rural nursing, which are often underestimated. Such understanding is essential to inform policy, tailor professional training, and guide the creation of sustainable support systems for rural healthcare workers.

The implications of this scoping review for rural health contexts are significant: it urges health systems and educational institutions to rethink professional training, policy-making, and organizational support in ways that are attuned to the unique demands of rural nursing. In daily practice, the findings emphasize the need to develop strategies that help rural nurses transform work-related suffering into creative engagement – whether through peer support, access to continuing education, or institutional recognition. Ultimately, improving the mental health of rural nurses demands both systemic action and individual coping strategies, positioning pleasure not as a privilege, but as a necessary condition for sustainable care delivery.

Regarding the limitations of the study, it is worth highlighting the inclusion of only studies in three languages and the exclusion of some studies because the text was not available in full for free.

Conclusion

The work process of rural nurses is marked by a duality between pleasure and suffering, reflecting a complex interplay of professional isolation, work overload, lack of recognition, and inadequate resources on one side, and deep community bonds, autonomy, and personal fulfillment on the other. This review highlights that, while suffering is an inherent aspect of healthcare work, particularly in rural settings, it can be transformed through targeted support and strategic interventions.

Balancing these forces requires the implementation of coping strategies at both individual and institutional levels. Healthcare systems and educational institutions must recognize the psychosocial dimensions of rural nursing and actively invest in measures that promote wellbeing, continuing education, and meaningful recognition.

Ultimately, acknowledging and addressing the emotional experiences of rural nurses is essential for sustaining both workforce resilience and the quality of rural healthcare delivery.