Introduction

The rising prevalence of chronic diseases, changing demographics and complexities of health care, is accompanied by increasing interest in developing and delivering palliative care services1. This interest encompasses rural areas internationally2-4 and in Australia5,6. Regardless of location, palliative care is ‘an approach that improves the quality of life of patients ... and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness ...[using] a team approach to support patients and their caregivers’7. Thus, due to their importance in palliative care, there is a requirement to consider family and carer needs to ‘directly inform the provision of appropriate support and guidance about their role’ 8. Support for carers includes education and training9, standards to guide involvement10 and navigation programs11. However, despite such strategies, meaningful support and guidance for carer roles in palliative care are difficult to deliver12. Carer roles in palliative care are complex.

Carers play multiple roles in palliative care including caregiving, enhancing welfare, carrying out tasks, facilitating palliative care, taking responsibility for continuity of care, being an apprentice, managing suffering and making decisions at the end of life13. Through these roles, carers provide physical, emotional, social and spiritual support8 whilst contributing to healthcare economics12,14. Personal benefits such as increasing esteem and competence may also occur12. However, these roles are not without challenges. As palliative care is shaped by social and cultural dimensions, carers can experience ‘social inequalities, isolation … [and] role ambiguities’15. They may be confronted with the emotional labour of caregiving16, their own physical and psychological issues, varying responsibilities, the risk of financial disadvantage and social isolation17, unpreparedness for their role18, implications of limited experience with death and dying12 and issues related to fragmented health services8,12,14.

Furthermore, carers in rural areas can face location-related challenges that can arise from misconceptions about palliative care, late involvement of palliative care services, lack of trained providers, inadequate pain and symptom management, poor understanding of the impact of disease progression and paucity of local health care, such as home help, information and bereavement services2,4,19. However, carers in rural areas may also be positively supported by rural attitudes, such as resilience, acceptance of death and engagement in community support networks5. The constant fluctuation between encountering personal benefits and facing challenges contributes to the complicated role of the carer and their involvement with palliative care services. Thus, recognising the complexity of palliative care as a basis for carers’ experiences is key to informing meaningful support for carers20.

Discourse surrounding complex human experiences often uses metaphors21. Metaphors are ‘a figure of speech in which a word or phrase is used to describe something it does not literally denote’22 and can be a ‘cognitive device for interpreting the world around [us]’ 23. The metaphor of the journey is often used in health24 and palliative care25,26, including for carers27. While the journey metaphor has value for engaging emotions, movement and connections over time and space24, it cannot adequately capture the complexity of caregiving. Inadequacies of the journey metaphor have also been identified, including being too linear and ‘too directive in framing patients’ experiences’24 and providing a sense of passivity28. This inadequacy can be addressed by using a range of metaphors17,24. Thus, we identified scope for framing caregiving in palliative care as a journey that involves actions and needs to be navigated.

Interestingly, the metaphor of navigation is also receiving considerable attention in the literature in relation to many areas of health care, including carers of cancer patients29, aged care30, end-of-life care31 and chronic diseases32. However, similar to the journey metaphor, we identify that navigation can also convey a sense of directing carers along predetermined paths. For example, literature related to navigation tends to focus on evaluating the success of navigation programs33, documenting and educating for navigator roles34 and articulating processes for the implementation of models35. We deliberately chose to use the verb form of navigation, that is ‘navigate’, as an action-based metaphor. We used this verb form to deliberately position us to embrace the complexity of carers’ involvement in palliative care and be open to their individual paths. Through the use of this verb, we intended to explore what is ‘active, immediate, particularised and person-based’13. We sought to embrace complexity, explore beyond the limitations of journey and navigation metaphors and be open to multiple understandings. Our interest aligns with the recognised need to advocate for the voices of families and carers by understanding the carer experience through specific research projects rather than just the ‘routine annual collection of data’36.

Methods

Aim and purpose

The aim of our interpretive research was to understand the experiences of caregivers navigating palliative care in their rural settings. The purpose of the research was to develop a conceptual framework to inform reflections and discussions about providing deliberate, responsive and meaningful support for carers involved in palliative care.

Research approach

This qualitative study was informed by philosophical hermeneutics37, whereby the focus was on interpreting experiences rather than describing them. Previous knowing was recognised as a lens for interpreting38. Language was viewed as a way of knowing the world, and questions created opportunities for thoughtful responses and ongoing reflections38. Tools used in this research approach included the hermeneutic circle (for iterative returns to the data being interpreted), question-and-answer dialogue (posing new questions through these iterative returns to develop new understandings) and fusion of horizons (when the researchers’ horizons of understanding and those presented in the data reach a place of understanding)38. The linguistic focus of philosophical hermeneutics aligned with our intention to be sensitive to language without explicitly analysing metaphors used by participants.

Research context

The research team was composed of three medical students and two qualitative research supervisors in an Australian rurally located inland city. Our research context is explained in Box 1.

Box 1: Context of research39-44

|

The Australian rurally located inland city, in which the research was undertaken, has a population of almost 65,000 and a population density of approximately 6.5 persons per square kilometre. In contrast, the closest major city is 3.5 hours’ drive away, with a population of just over 171,000, and has a much higher population density of 917 persons per square kilometre. Consistent with the Australian models of palliative care provision39,40, our local area has specialist palliative care providers based in the hospital and generalist community services. However, despite these services, our location is part of the widespread deficit of palliative care services in rural, regional and remote Australia. Accordingly, locally based palliative services can be accessed in conjunction with in-person or telehealth support from metropolitan-based palliative care services40. |

|

The research was undertaken over 2 years as part of the requirements of the students’ (authors 1–3) medical degrees. For the second year of the research, the students were co-located with their supervisors while they undertook a year-long rurally based clinical year through the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training Program41. This program was part of a government initiative to educate healthcare students in rural areas as a key strategy to address workforce maldistribution. The supervisors have been researching rurally in the location for over 15 years, including collaborative research involving local palliative care clinicians42. |

|

By undertaking the research in the interpretive paradigm, students were required to engage with ways of understanding that extended them beyond the socialisation of the empirico-analytical research paradigm, a story that was shared in a conference presentation as they were finishing their 2-year research project43. Their learnings provided rich insights into the context of the research, including engaging with the method. |

|

While undertaken in a rural region, we were not seeking for this research to be representative of diverse rural settings44. Rather, we are providing the information in this Box to facilitate transferability of our findings so that readers can use their understanding of their own contexts to establish the relevance of our findings to their situations. By explaining our personal engagement with our rural context, we explicitly provide our ‘beginning horizons of understanding’, which is integral to our research approach. |

Participant recruitment

We used local clinicians for recruitment to ensure carers’ experiences of palliative care could be discussed safely. Participants were carers who had previously cared for patients requiring palliative care. Based on their personalised knowledge and relationships with patients, clinicians approached potential participants according to the criteria described in Box 2. If carers expressed an interest in participating, clinicians provided recruitment material. Participants were contacted by the research team after we had received their signed consent forms. We then arranged interviews for a mutually convenient day and time. Eight caregivers participated in the research (Table 1). The adequacy of this sample size was justified in relation to sufficient diversity of participants for the topic and method45 and awareness of the burden on participants and consideration of resources46. We highlight that our sample size reflected the outcome of a deliberate balance between the sensitivity of the topic, scope for deep engagement through semi-structured interviews, recruitment requiring established carer–clinician relationships, the rural location with a relatively low population density and workforce shortages, and considerations for research informed by philosophical hermeneutics.

Box 2: Eligibility criteria

|

Local medical practitioners used the following criteria to determine carers’ suitability to participate:

|

|

To ensure diversity of experience, participants were not excluded based on the nature of their caregiver role or time spent caring. |

Table 1: Participant demographics

| Variable | Characteristic | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 6 |

| Male | 2 | |

| Relationship | Spouse | 4 |

| Parent | 1 | |

| Sibling | 1 | |

| Child | 2 | |

| Condition | Cancer | 5 |

| Neurodegenerative | 2 | |

| Congenital | 1 | |

| Nature of care provided | Locally based rural care only | 2 |

| Locally based rural care with metropolitan services via telehealth | 2 | |

| Locally based rural and in-person metropolitan services | 4 |

Data collection and management

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews of between 1 and 1.5 hours. Participants were interviewed by two members of the research team, one conducting the interview and the second acting as a reflective listener. Four main areas were explored: involvement in palliative care; key aspects of their lived experiences as a carer; how they navigated palliative care systems and carer emotions; and how a rural setting impacted their experiences as a caregiver. Seven interviews were face-to-face, undertaken at the educational facility, and one was performed via videoconference due to COVID-19 requirements. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim via professional transcription services. Transcripts were cross-checked with primary recordings and de-identified using pseudonyms, including non-gendered pseudonyms for some participants. Data were managed in NVivo 1246. Reflective journals were kept by researchers to articulate beginning and developing horizons of understanding, questions to ask of the data and own understandings, emerging conceptual frameworks and details of the process.

Analysis

Interpretations were individual, collaborative and iterative, involving cyclical phases of analysis as we moved between individual and collective engagement with data, participant quotes and whole transcripts, data and reflective journals and individual and collective understanding (hermeneutic circle). We had ongoing returns to the data to move to conceptually higher understandings (question-and-answer dialogue) that were portrayed through three dimensions (fusion of horizons)38. Examples of this layered iterative, collaborative, dialogical process captured through a video presentation44 provide an authentic, contextualised illustration of our critical creativity. Consistent with reporting of qualitative research findings, we were open to presenting our findings through metaphor47, but analysis of metaphors used in participants’ stories was not the primary lens used in the dialogue of question and answer.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval No H-2020-0408). Risk mitigation and duty-of-care strategies were put in place for the students, researchers and participants.

Results

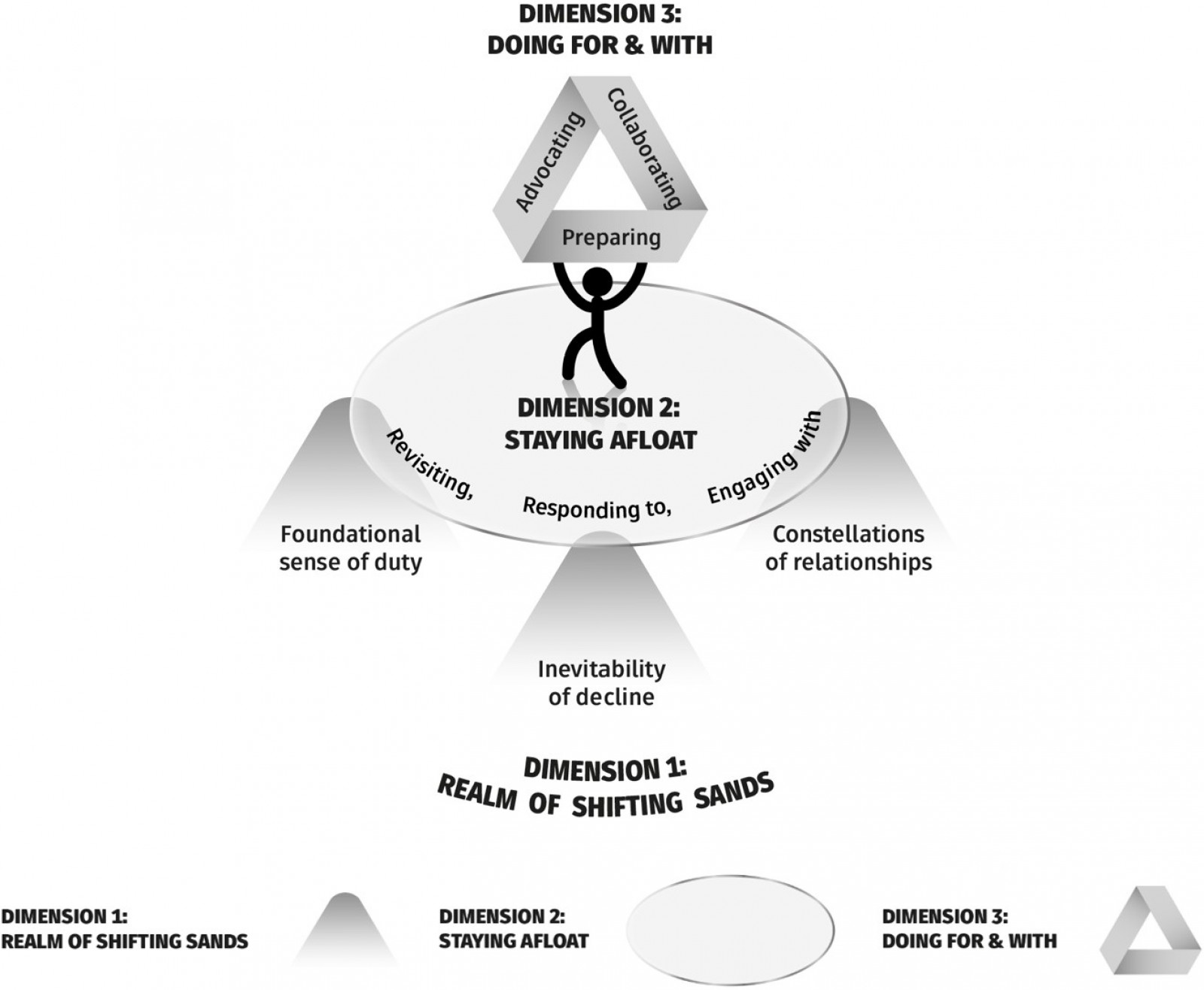

The experiences of carers as they navigated palliative care were interpreted as three interrelated dimensions: ‘realm of shifting sands’, ‘staying afloat’ and ‘doing for and with’.

Realm of shifting sands highlights the diversity and potential fragility of terrains carers are navigating, that is foundational sense of duty, constellations of relationships and inevitability of decline. Staying afloat highlights the dynamic responses required to navigate these terrains, that is revisiting foundational sense of duty, engaging with constellations of relationships and responding to the inevitability of decline. Doing for and with highlights the multiple actions as carers hold their course and participate in palliative care, that is advocating, preparing and collaborating. This conceptual framework is illustrated through quotes and scenarios. The first two dimensions, illustrated by a range of participant quotes, highlight diversity, fragility and responsiveness. The last dimension is illustrated by two scenarios to highlight its interrelatedness, in relation to both its own elements and to the other dimensions. The term ‘their person’ rather than ‘palliative care patient’ is used to emphasise the relationship with the person receiving palliative care, rather than their relationship with healthcare systems and services.

Being in a realm of shifting sands

The title of this dimension originates from a participant’s words that provided a sense of the diversity and fragility of the terrain being navigated by caregivers.

We lived on shifting sands … Just when you thought things were settled, something would just be pulled out from under you, and you’d have to fight again. (Sue)

As described below, the ‘realm of shifting sands’ has three elements that are part of the terrain being navigated.

Foundational sense of duty

Sense of duty formed a solid foundation for carers. While responsibility and inevitability were inherent to this element, its origins and implications varied. For example, Sam deeply felt responsibility for family members as the basis of being a carer:

I was just doing what had to be done ... You just do it don’t you? You’ve always just done it, whether it was your mum or your dad, your husband or your son, your daughter. You just looked after them. (Sam)

For one participant, it was a passed-on obligation that began abruptly:

I had a younger brother who basically had an intellectual disability … the day my father died, my brother ... came to live with us. (Kat)

For some, the sense of duty was uncontentious:

It was easy for me to do because I’m an only child. So, I was divorced, I don’t have kids ... but it was a pleasure. (Pat)

For others, there were potential tensions shaped by personal situations. Kat’s foundational sense of duty was amplified due to her healthcare background. She felt a level of societal pressure related to the professional skillset she brought to her caregiving role. This amplification resulted in potential discord between her identity as a health professional and as a person with a pre-existing relationship with their person:

Because I was a healthcare worker, there was that expectation that I would take this in my stride. But it’s not the same when it’s your own. (Kat)

While a foundational sense of duty was core to the caregiving role, it was experienced differently across different personal situations.

Constellations of relationships

Carers were in the midst of a range of relationships, where they could draw on established relationships and form new ones through their involvement in palliative care. Pat explained the value of positive relationships:

We had the support of people at church, very genuine … [doctor’s name withheld for anonymity], he was great. He was very personable, and the oncology nurses were just a breed above. They were funny, they were kind. (Pat)

Relationships and their value could be shaped by location. For example, Sam valued opportunities to connect in person with key support people from her rural setting:

Here, we were five minutes from everywhere. So that sort of role, from that perspective, I think the regional town was an advantage. (Sam)

Sky’s experiences with health services in a distant metropolitan area enabled his deeper appreciation of the readily accessible local services he had at key times of personal need:

I rang his rooms [in my local area] to say that she passed away … [he] asked me to come in. So, I went in and had half an hour talking to him about it. (Sky)

Relationships across distance could be challenging, particularly when accompanied by a lack of understanding or consideration of carers’ personal situations and locations. Continuing with Sky’s example, he also expressed his frustration in connecting with a metropolitan-based caregiver service:

The only thing I ever got there was an email … would I like to go to lunch at [metropolitan] Hospital. And it was pretty much useless. I wrote back saying, no I’ll be back here [in his rural setting] that day looking after my wife ... That used to annoy me. (Sky)

Diverse personal and location opportunities shaped access to and availability of relationships with key people.

Inevitability of decline

Ultimately, at the core of every palliative care journey was the inevitable decline towards death:

We just took each day as it came. As his condition changed, we just adapted really. (Vic)

The inevitability, while always being the reason for palliative care, could be accompanied by gentle awareness and acceptance:

He had his little bowl of porridge and he just sat there, didn’t say anything. The kookaburras were chattering away … we all knew it was kind of the end. (Rae)

However, it could also be a contradictory concept where it was simultaneously predictable and unpredictable. Sue demonstrated this when expressing the abrupt death of their daughter:

On the night she died, I’ve seen her way more sick than she was the night she died. So, I was really shocked at how she died that night. (Sue)

Caregivers could experience feelings of incompetence, unworthiness and hopelessness when faced with the inevitability of decline, and those emotions could transcend time. Even after death, caregivers may wonder how or what they could have done to ameliorate the outcome. Vic recalled how her husband’s illness regressed and limited his ability to eat solid foods:

Every now and then he’d want to have something normal. Like if we were having a pizza and he came in and took a couple of bites and we ended up having to call an ambulance because he was choking ... you can still visualise these situations. (Vic)

The inevitability of their person’s decline was associated with a range of implications and potential contradictions of particular situations and responses.

Staying afloat

The title of this dimension captures the dynamic responses needed to navigate the changes and, perhaps, fragility of their realm of shifting sands. These responses involved making sense of and participating in the shifting sands.

Revisiting foundational sense of duty

Particular moments encountered during their person’s journey required carers to revisit their foundational sense of duty. This could involve being aware of the implications of going beyond their comfort zones.

But for me to use morphine was a massive, big deal because I was so frightened that I’d be the one that would give her that final dose and that would be it ... I wasn’t going to step away ... And I had to just make the choice. (Sue)

Through revisiting their foundational sense of duty, personal limits of involvement could be set.

I don’t wash my brother, you know … there’s a line I have to draw here. (Kat)

Despite being core to the role of carer, a foundational sense of duty did not necessarily dominate all carers’ relationships with their person. For some, there were moments where pre-existing relationships took precedence over the later-occurring carer role.

And then the gift I got given … I was allowed to be dad’s daughter for the last week, not the carer. I was allowed to just be me, not have to worry. (Ash)

For others, their foundational sense of duty became less about required activities and more about being in the moment with their person.

It became a different sort of friendship, and it was quite lovely … he wanted me to lie down in the bed just next to him … And we didn’t have to say anything. (Rae)

While the foundational sense of duty was core to the terrain carers navigated, it was not necessarily straightforward or constant over time.

Engaging with constellations of relationships

Engaging with constellations of established and developing relationships provided a range of opportunities for carers. Sam described how supportive relationships were able to disrupt initial perspectives.

Get rid of that misconception that palliative care is just a place you go to die. It’s not. Palliative care is so much more, and the carers that are there and the support that’s there. (Sam)

Through their relationships with palliative care staff, carers were able to make sense of the new unknowns and maintain aspects of normality.

So, from then on [my husband] had a whisky at night down the PEG tube. He found out that it was not going to hurt him. (Vic)

Locations could enable expanded valued relationships. Ash articulated her appreciation for her location, and how her experience shaped others’ relationships with palliative care.

[Rural location] is particularly fabulous. I think it’s more accessible. So not only have I had mum and dad, but my next-door neighbours also … I got their daughters to get them into palliative care because they’d both ended up with cancer at the same time as well. So, I found that was easy. (Ash)

However, not all constellations of relationships were completely positive and constructive. Discrepancies in expectations could create tensions that needed to be understood to be addressed. For example, in her caring duties, Ash needed to make sense of her siblings’ needs and balance competing agendas within her family:

But they [siblings] didn’t let dad sleep … they wanted his response, but it was too late. Dad was too tired to respond … I had to sort of step back, because I couldn’t say don’t do that, because they would think that I was depriving them. (Ash)

Engaging with constellations of relationships provided a range of opportunities for sensemaking and participating. Such opportunities could be supportive as well as challenging.

Responding to the inevitability of decline

Particular trajectories of their person’s decline, the relationship with their person and their own personal circumstances shaped the ways carers responded over time. There may be moments of intense unfiltered reaction, as described by Sky.

You see your partner slipping away gradually a bit each day. And that’s really, really hard. I find that very hard. And things like she’d say, you’ll be glad when I’m gone, and I’d just burst into tears. (Sky)

Making sense of their own responses to their participation may be challenging and remain unresolved, particularly if there were immediate needs to participate and opportunities to process uncertainties were missed.

I wasn’t trying to be cruel, I was just frustrated. No one to talk to about how I was coping, you know, which I obviously wasn’t … What was the point of really complaining … I suppose I’ve not really given it a lot more thought anymore because it’s nothing I can change now. (Kat)

Participating in difficult decisions could be a challenging aspect of responding to the inevitability of decline of their person.

At the end of the day, he was always going to die … the hardest thing was making that decision for no further treatment. (Kat)

Sensemaking of the inevitability of decline could involve future projections, as Sue described in relation to the inevitable decline of her child:

Over the following years, I would look at her and then things start sinking in, but I could never picture her as an adult. (Sue)

While carers responded to the inevitability of decline, their participation and sensemaking was not always smooth going or easy to resolve.

Doing for and with

By staying afloat in the realm of shifting sands, carers’ position themselves for the actions of advocating, preparing and collaborating. The scenarios in Table 2 describe aspects of the carers’ realm of shifting sands that bring about their revisiting foundational sense of duty, responding to the inevitability of decline and engaging with constellations of relationships. This navigating ultimately allows the carer to participate in doing for and with their person and others, demonstrating the interrelatedness of the dimensions.

Table 2: Scenarios depicting the actions of advocating, preparing and collaborating

|

Scenario 1 |

And I found him in this dark room with another person and there were boxes … in the hallway, and he had to negotiate getting around. I mean … granted it was all COVID and everything. So, I mean, I’m not blaming the hospital, but I just suddenly – I just thought we’ve got to take some action1. So, we did everything we could to get him out of the hospital and home, which meant a different sort of commitment from us. Because I really looked at him in that room and I thought … and he himself, he just said, %u2018I want to get out of here’. And he just wanted to be in his own bed, look out his own window2. And so anyway … we did manage to get him out. And so, then we had to sort of just get things in place at home. And also, I think in his own mind, we knew that down the track he was going to need different equipment … So, we had the physio that came, [physiotherapist’s name], who was wonderful, and also [doctor’s name], who was wonderful as well3. And so, she brought out, you know, different pieces of equipment. And he said, well, I don’t need that … she didn’t argue or anything. She just put it all back in the car and, you know, another week and a half, he did need some of those things. So, she came back [LAUGHTER] or actually I think our daughter picked it up from the hospital in a roundabout way because of all the COVID stuff4. So anyway, it was funny and challenging, I think, just doing things differently. (Rae) |

|

Scenario 2 |

So, at the bedside discussion they said they wanted to put him onto a syringe driver and they thought that was the best thing for him5, so that happened and that was Friday and we were able to come in on the Saturday to go into [the palliative care unit], but he just was asleep. It was as if they’d put him to sleep and I wasn’t able to [CRYING] communicate with him again … And so, on the Sunday morning the physician in charge came around to see him and, you know, he didn’t know [husband], he didn’t know the background and I just voiced my concern that he’s on the syringe driver, but I felt like I haven’t said good-bye6. So, he [the doctor] took that off of him just to see how things would go and by [that] evening he was starting to get agitated … So, we went back on to the syringe driver which I realised he needed, but with less sedation so that we could still communicate7 … We left it at that and [doctor’s name] explained to me that the BiPAP or the CPAP was really what was keeping [husband] going, keeping his lungs working, the best thing to do would be to remove that and then he’ll pass away … and we just took the machine off on the Tuesday morning8. End of journey … [CRYING] (Vic) |

1Rae was met with the inevitability of decline and responded to the situation by revisiting her foundational sense of duty, which propelled her to participate in advocating and preparing for her person.

2Another driving factor behind her urge to advocate for her person, was her recognition of her duty to collaborate with her person as well.

3Rae recognised the need to engage with her constellations of relationships, which in this case were the physiotherapists, to enable her to respond to the inevitability of decline and thus meaningfully advocate for and prepare her person.

4Rae’s multiple engagements with the physiotherapist reinforced the ongoing act of staying afloat during caregiving and also reiterated that a collaboration with others can influence the success of advocating, which furthers not only the interrelatedness of the dimensions but also the intertwinement of actions of doing for and with.

5Vic was met with the inevitability of decline in her realm of shifting sands.

6Based on her sensemaking throughout the changing situation, Vic engaged with her constellations of relationships, which was the medical team, and sought for a level of collaboration.

7Whilst preparing herself and her person for the decline, Vic revisited her foundational sense of duty, which was to ensure her person was not distressed or in pain. This sensemaking enabled her to stay afloat and allowed her to advocate for her person by ensuring they resumed the syringe driver.

Discussion

Our research addresses the need for palliative care research that explores the experience of families and carers and ensures that their voices are heard48. While the project is the first qualitative research to explore the experiences of caregivers navigating palliative care in their rural Australian settings, our findings support existing sentiments of the cruciality of recognising the complexity of caregiving in palliative care5,19. Through our research, we developed a conceptual framework highlighting that carers navigating palliative care in their rural area were in a realm of shifting sands, where they were staying afloat in order to be doing for and with their person. Issues identified in previous research can be located in this conceptual framework. The realm of shifting sands, for example, can encompass the notion of responsibility13,49, end-of-life decisions13 and support networks18. Staying afloat can encompass being confronted by the emotional labour involved16,50, being unprepared for their role12 and engaging with support networks51. Doing for and with can be an umbrella for the range of different carer actions, including carrying out tasks, managing suffering and making end-of-life decisions13. Through its scope to engage with complexities, our conceptual framework can inform ongoing reflections and discussions to provide meaningful support and guidance.

Based on our conceptual framework, we invite careful consideration of the diversity and potential fragility of terrains carers navigate (realm of shifting sands), their dynamic responses as they navigate these terrains (staying afloat) and the multiple intertwined actions that are possible in participating in palliative care (doing for and with). Complexities can be framed in relation to individual reference points, personal capabilities, particular circumstances as well as locational factors, and not all complexities relate to their rural setting. For example, the foundational sense of duty involves an individual reference point and how this is revisited over time may rely on personal capabilities. The inevitability of decline relates to the particular circumstance of their person’s illness, and responding to this inevitability may rely on carers’ capabilities with sensemaking, along with resources from their particular locations. The constellations of relationships and how the carer engages with them is similarly dependent on varying factors, including their access to key people or supports in particular locations, and personal capabilities for creating new connections or maintaining established ones. Advocating, collaborating and preparing are also reliant on carers’ personal circumstances for participation, which can be influenced by what is available in their particular locations. The significance of rural settings, when applicable, often encompasses more than locational properties and can involve the community, values and personal connection they imbue to the caregiver. These, in turn, comprise one of a range of complexities that can both hinder and enhance carers’ sensemaking and participation in palliative care.

In Figure 1, we present a graphic representation of our conceptual framework. In this visual format, the metaphors inherent in the titles of the dimensions are more obvious. The realm of shifting sands is depicted as three mounds of sand with dissolving foundations. Staying afloat is depicted as a person precariously balancing on a platform atop the mounds, working hard to position themselves for the actions of doing for and with. The actions of doing for and with are intertwined actions that twist on themselves and run into each other but represent a cohesive whole. Although identifying metaphors was not the intentional outcome of the analysis, they became necessary to capture the complexity, and evoke a sense, of the carer experience. Their scope to capture this complexity is consistent with the ‘power of conceptual metaphors to accurately explicate cultural assumptions and behaviour in the medical practice milieu’52. In Box 3, we share our intentions behind the visual elements of the model.

Figure 1: A caregiver dynamically navigating situational complexities associated with their role in palliative care.

Figure 1: A caregiver dynamically navigating situational complexities associated with their role in palliative care.

Box 3: Intentions behind the visual elements of the model (from bottom to top of model)

|

Dimension 1: Realm of shifting sands

|

|

Dimension 2: Staying afloat

|

|

Dimension 3: Doing for and with

|

|

At first glance, the model can appear abstract and complex. However, by breaking down the model into dimensions and then into individual elements, it becomes apparent that there is an interrelatedness between each aspect, where one cannot exist without the other. |

Of note is the inherent ambiguity and, at times, dissonance that exists within the metaphors. The realm of shifting sands evokes a myriad of imagery, from vast endless sand dunes to the totality of a singular pool of quicksand. This, in turn, reflects the variety of circumstances and experiences caregivers face depending on individual circumstances. In response, staying afloat implies not only a lack of forward movement but also a struggle to be positioned and involved in palliative care. Importantly, doing for and with does not involve an obvious metaphor. Rather, the title of this dimension describes the actions of being involved as a carer in palliative care as they are staying afloat on shifting sands. There is an additional dissonance in how the metaphors represent navigating. The sense of instability and directional ambiguity contrasts with the planned path and waypoints that are often associated with navigating. Rather than providing a clear picture of navigating linear, straightforward or passive actions, the metaphors combine to form an impression of constant motion, adjustment and effort.

The range of metaphors and dissonance between them create a rich space for reflecting. Such reflection can inform ongoing practice. Thus, we encourage health professionals, students and others, to recognise, reflect, dialogue and respond to the inherent complexities of being a carer navigating palliative care and how our findings might relate to their own particular situations and practices, including currently available supports such as navigation programs. As guidance in this space, we have developed some reflective questions as shown in Box 4. The questions may be considered individually or collectively and in reference to particular carers or carers in general.

Box 4: Reflective questions

|

Think of an experience when you or someone else was in a caregiving role:

|

|

*From our perspectives as the medical student researchers who undertook this project to now graduated health professionals, our research has not only impacted our clinical spheres but also has enabled transferability of our reflections into our personal lives. Our awareness of the multifaceted nature of caregiving has allowed a sense of relating when interacting with patients and their caregiver(s) and serves as a constant reminder to be diligently attentive to their diverse and complex needs. |

The strength of our research was our in-depth exploration of particular experiences, the development of a conceptual framework that transcended particular situations and our focus on exploring services available in rural areas, rather than exploring issues related to the absence of services. Another unexpected strength was the value of the reflective questions, such as those in Box 4, which inspired one of our researchers to pursue a career as a rural generalist with a focus in palliative care. Our findings also helped another member of our research team in their processing of their own lived experience and grief as a secondary palliative caregiver. A key limitation of our research was being confined to one rural area due to feasibility. However, consistent with research in the interpretive paradigm, we aimed for transferability by making explicit our context and method to enable readers to judge the relevance and usefulness of the findings to their own contexts (rather than the generalisability of objective quantitative research, where the writers aim to establish the extent of relevance for others)53. Our findings raise further research questions, including: how can conditions be created for health professionals to deliberately, responsively and meaningfully support carers navigating the complexities of palliative care?

Conclusion

Beyond the importance of getting palliative care services into rural areas is the need to support the carers (and others) who are supporting their person in accessing the palliative services that are available to them. Our research explored the experiences of carers navigating the complexities of palliative care services that were available and accessed in rural areas. These complexities can be framed in relation to individual reference points, personal capabilities, particular circumstances as well as locational factors. Recognising the complexity of navigating the terrain, responses and actions related to these elements provides a sound basis for ensuring that the support is deliberate, responsive and meaningful. Importantly, such support may not necessarily remove the complexities, rather it may involve recognising, reflecting on and being responsive to complexities at appropriate times in appropriate ways. Time and resources for reflection and supportive responses to complexities may be a good beginning in aiding caregivers as they navigate their unique and complex role in palliative care.

Funding

Two authors (AC and KF) were employed at the University of Newcastle Department of Rural Health at the time of conducting this research. The Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training Program through which the authors were employed is funded through the Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training Program.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.