Introduction

Remote or rural living poses unique challenges to mental health. In the UK, rural areas are characterised by small settlements, extensive agricultural land and lower population densities1. The distance from urban centres means that those living in rural areas often lack accessible health services, potentially leading to delayed treatment and poorer outcomes2. Scotland has a significant rural population, with approximately 17% of the population living in rural areas3. These areas cover about 98% of Scotland's land mass, highlighting the extensive geographical spread3. The geographical remoteness of rural areas can foster social isolation, known to be linked with poorer mental health4. Moreover, the sparse mental health services in these areas, compounded by potential transportation barriers (eg a lack of viable public transit options, heightened rural fuel costs)5, highlights the relative difficulty in formal service provision. This means that informal sources of support are even more important. Understanding factors related to this support is thus a key issue for rural health improvement.

Social relationships are crucial for mental health, providing emotional support and facilitating access to care6. However, individuals living in rural areas are often challenged by a culture that discourages open discussion of mental health issues, particularly among men due to traditional rural masculinity norms7,8. Sociodemographic factors in rural areas, such as lower mental health literacy9, can further contribute to the reluctance to engage in conversations about mental health. Perceived stigma surrounding mental health can make individuals reluctant to share their struggles even informally. For example, recent research has found that rural residents often feel the need to maintain a ‘stiff upper lip’ and avoid discussing personal problems to not appear weak or vulnerable10. This fear can be exacerbated by the characteristics of rural social networks, which are typically small and offer little privacy or discretion11,12. The tight-knit nature of these communities can amplify concerns about confidentiality and lead to a heightened sense of exposure when discussing personal struggles11-13. Therefore, it is essential to understand how rural residents navigate these complex social and cultural dynamics when addressing mental health issues within their communities.

The functional specificity hypothesis posits that people selectively engage with different members of their social networks14. That is, individuals assess the fit between the issue at hand and the social resources available within their surrounding social network. A particular type of relationship or person may be perceived as effective for one kind of task or problem, but not another15. Within this framework, individuals make strategic choices about which ties in their social network, if any, would be amenable to discussions around mental health. To understand these choices, it is necessary to consider characteristics of the individual, as well as characteristics of the social contact (eg their gender) and aspects of the relationship (eg their emotional closeness). Given that social interactions are the product of the wider social ecosystem16, it is also necessary to consider the structural features of networks (eg the size of the network).

Indeed, research demonstrates that characteristics of individuals, attributes of relationships and features related to social network structure can all affect mental health discussions. For example, women are generally more likely than men to disclose mental health issues, and stigma can significantly reduce the likelihood of disclosure13,17,18. Perry and Pescosolido found that individuals prefer discussing mental health with close network members who have personal experience with mental health issues19, while Thoits found that people are more likely to disclose mental health issues to those from whom they receive social support, typically family and close friends20. In a study of social network factors influencing the decision to share suicidal thoughts, Fulginiti et al found that relational factors (eg support) predicted disclosure patterns above individual characteristics of the social contact (eg ethnicity)21. Studies have demonstrated the importance of structural features of networks, both at the level of the social contacts in the network, as well as the overall network. For example, social contacts who were more connected to others in the network (ie exhibiting high ‘degree scores’) were more likely to provide social support to individuals with a diagnosed mental illness in a previous cross-sectional study22. Larger overall network size has also been associated with lower likelihood of engaging in mental health discussions among those experiencing an episode of poor mental health19. This is hypothesised to be because larger networks may lack cohesiveness and be less cooperative.

To date, there is a paucity of research examining mental health discussion networks focused specifically on rural settings. Moreover, current literature relies heavily on clinical samples17,18. Given the unique context of mental health in rural areas, there is a particular need to understand which types of social relationships are conducive to discussions of mental health. As such, this study examines with whom rural residents in Scotland discuss mental health, using novel social network data. It identifies the characteristics of individuals and relationships that relate to mental health discussions, and how network structures are associated with these interactions. The findings can inform the design of relational interventions to improve mental health support among rural residents, leveraging existing social ties and fostering new supportive relationships.

We address the following research questions:

- What are the characteristics of individuals (rural residents and their social contacts) that make mental health discussions more likely?

- What are the characteristics of relationships that make this more likely?

- Which characteristics of networks make mental health discussions more likely?

Methods

Data

Data come from 505 social contacts of 20 participants from the Social Connections, Health, and Wellbeing in Scotland Study, conducted in 2021. The cross-sectional study aimed to depict the links between social connectedness and health in Scotland. This manuscript focuses on a subset of data from the full Social Connections, Health, and Wellbeing in Scotland Study – detailed social network data obtained from 20 study participants living in rural Scotland (see Long et al (2024) for details on the full study23). The Scottish Government six-fold Urban–Rural Classification3 was used to designate a ‘remote rural area’ consisting of participants who resided in communities of fewer than 3000 residents in the Scottish Highlands. The Highlands encompass approximately one-third of Scotland's land mass, but contain less than 5% of its population, including disconnected towns and villages with few commuting or accessible transport options between3.

An online survey collecting demographic and health data was administered between the months of April and July 2021. Participants indicated whether they consented to taking part in a follow-up, detailed social network study. Twenty rural participants agreed, and then completed an online egocentric social network survey using Network Canvas software v4 (Complex Data Collective; https://networkcanvas.com)24 within 1 month of survey completion. Egocentric social network25 studies consist of asking study participants (‘egos’) about their social contacts (‘alters’), creating a ‘personal network’. In the current study, participants were asked to provide the names of individuals (1) they had recently interacted with; (2) they hadn’t had a recent interaction with, but still considered part of their social network; and (3) anyone they frequently interacted with, but didn’t know well or didn’t know their name. Participants then provided data about their social contacts’ characteristics (eg demographics) and aspects of the relationship (eg length of time known). Participants also indicated whether their social contacts knew each other, which provides measures of network structure (eg the density of each participant’s personal network).

Measures

Outcome

A binary variable indicating whether each social contact was listed as a mental health discussion partner (0 = ‘no’, 1 = ‘yes’) was created. After participants provided the names of each of their social contacts, they were asked ‘Who would you feel comfortable talking to about your mental health? For example, telling them if you started going to therapy, or received a mental health diagnosis.’

Individual characteristics

Gender of study participants and social contacts was coded as a binary variable, indicating man (0) or woman (1). Although additional gender identities were provided as possible responses, participants in this study did not select these. Age of study participants and social contacts was converted into a seven-point ordinal scale, representing 10-year age bands, ranging from 0 (≤20 years) to 6 (>70 years). A single item on participants’ mental health stigma was included, assessing their willingness to speak with a doctor about their mental health. This is a frequently used measure26 resulting in an ordinal scale of 0–4, with higher scores indicating greater levels of stigma. Participants’ subjective wellbeing was measured using a three-item scale used by the Office for National Statistics27, capturing life satisfaction, happiness and feelings that things in life are worthwhile. Each item is rated on a scale of 1–5. Items were summed, creating a variable with a range of 3–15 (Cronbach’s alpha 0.88).

A number of additional individual characteristics about study participants were not retained in the statistical models due to sample homogeneity, or high correlation with other variables. For example, we tested variables such as financial situation, ethnicity, loneliness and general health.

Characteristics of relationships

Relationship length between study participants and each of their social contacts was measured on a five-point ordinal scale, including 0 (<1 year), 1 (1–2 years), 2 (3–5 years), 3 (6–10 years) and 4 (>10 years). Frequency of talking was measured on an ordinal scale, ranging from 1 (less than monthly) to 5 (at least daily). Proximity between participants and each of their social contacts was measured with a question asking each participant how far they lived from the social contact, resulting in a variable ranging from 0 (live outside the UK), to 5 (live with social contact). Relationship type described the connection between participants and social contacts, including family, friend or other (mutually exclusive). Two measures of homophily between participants and their social contacts were created: one measuring whether they were in the same age bracket (0 = ‘no’, 1 = ‘yes’), and the other measuring whether they were of the same gender (0 = ‘no’, 1 = ‘yes’).

Characteristics of networks

Social network size measures the total number of social contacts listed by a participant, providing a general indicator of the number of relationships an individual has. Network size is also an important variable to control when assessing other structural features, such as alter degree or betweenness, and network density. Social network density is an indicator of the connectedness or cohesion of networks22, measured by the total proportion of social contacts who were indicated as knowing each other within a particular network. A binary indicator was created, measuring whether a participant’s network was above or below the mean density score of the sample (0.17). Higher scores represent more dense networks.

We also included two network measures of the embeddedness of social contacts in each network. Alter degree measured the total number of ties that each social contact had to others in the network. Alter betweenness measured the number of times that the social contact was on the shortest path between two other individuals in the network. Alter degree and alter betweenness are both measures of the centrality of social contacts within the network, with higher degree representing social contacts who may have access to more information about the participants (via their many links to others in the network), whereas betweenness represents individuals who occupy social positions that connect different social circles in the network (family v friends v colleagues).

Statistical analyses

Egocentric multi-level modelling28 was used to investigate ego (participant), alter (social contact), ego-alter (relationship), and network characteristics associated with mental health discussion. In this type of modelling, the unit of analysis is a tie (ie binary indicator of mental health discussion partner), and sample size is considered at the level of the social contacts (ie level 1; n=505). Multi-level modelling accounts for the clustered nature of egocentric data, in which social ties within one personal network are more likely to be similar to each other than social ties across the networks28. The intra-class correlation of our data (0.50) further justifies the use of multi-level modelling.

Our modelling procedure followed a stepwise progression. First, we fit a multi-level model (logistic) restricted to participant characteristics only, treated as a control model. We then tested a model with social contact characteristics, and relationship characteristics, followed by a model fit to network characteristics. After the three separate models had been fit, we then tested a final model that simultaneously estimated the significant parameters from the previous models. Network size was retained as a control variable for betweenness in the final model. Due to our relatively small sample size, we applied a statistical cutoff of p<0.1 in deciding which parameters to retain in the final model. The variance inflation factor was tested in all models to detect multicollinearity29 and the value was less than two. All analyses were conducted in R using the lme4 package30. Rates of missing data were low (0–6%), and therefore data was not imputed.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the University of Glasgow (approval number: 200200053).

Results

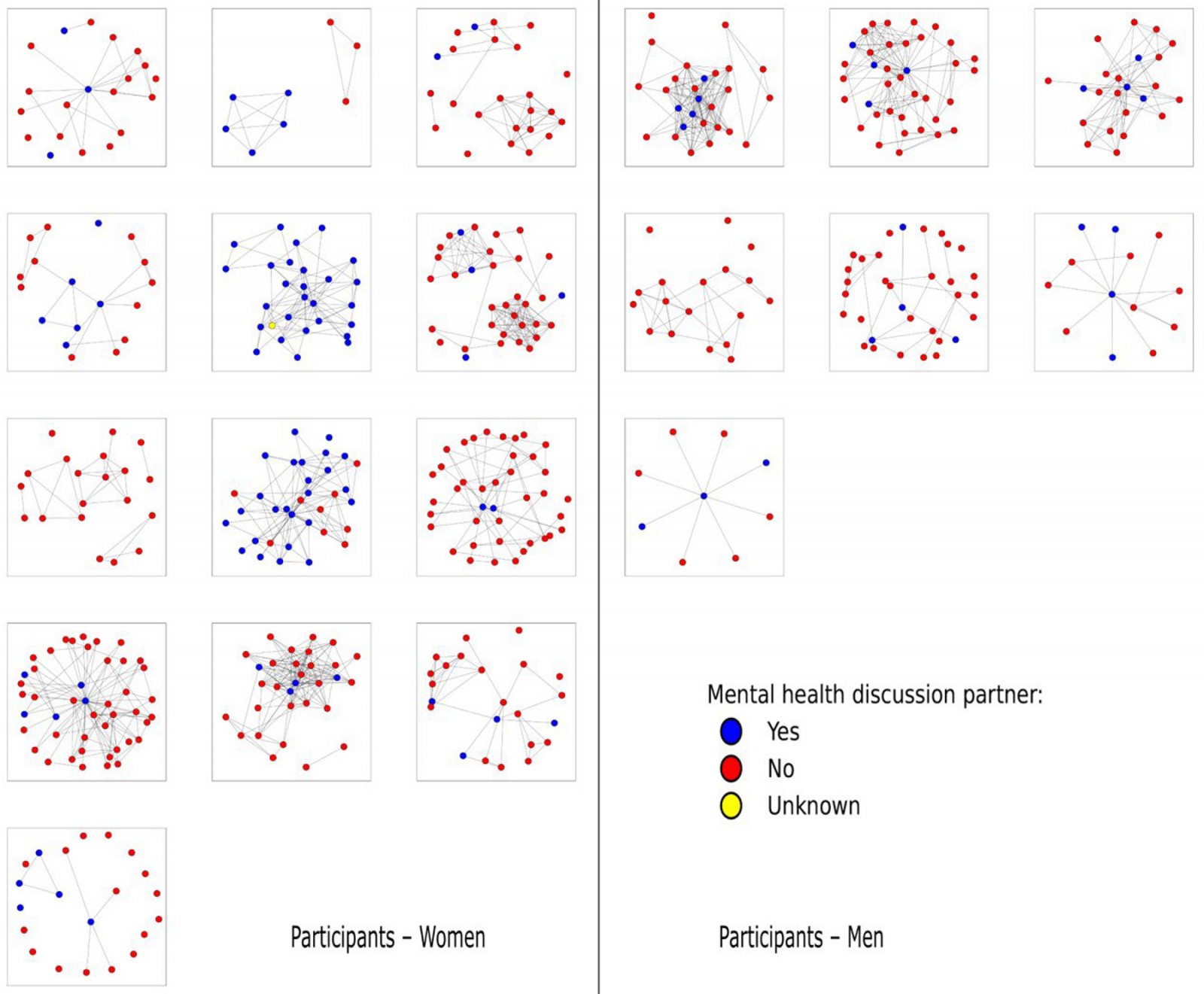

Descriptive characteristics of rural residents are provided in Table 1. Average participant age was 51 years, with the majority being women (65%). Participants tended to score low on mental health stigma (2.5, range 1–5) and high on wellbeing (11.35, range 3–15). Average network size was approximately 25 people. Figure 1 shows plots of the 20 personal networks, split across the two genders.

Descriptive characteristics of social contacts are provided in Table 2. About 38% of social contacts were labelled as friends, while approximately 30% were labelled as family and approximately 33% as other. Mental health discussion partners constituted 23% of social contacts. Social contacts tended to be women (56%), and individuals whom participants had known longer than 10 years (~55%). On average, social contacts knew approximately five other individuals in the ego’s personal network. Social contacts across the sample were distributed equally across the categories of age, talking frequency and physical proximity to participants.

Results from the sequential multi-level models are shown in Table 3. In the final model, participants with higher ratings of mental health stigma (odds ratio (OR) 0.38, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.17–0.85) had a lesser likelihood of reporting mental health discussion partners.

In terms of social contact characteristics, social contacts who were female versus male (OR 4.06, 95%CI 1.77–9.32), and of a younger age (OR 0.71, 95%CI 0.54–0.94) were more likely to be mental health discussion partners. However, homophily on gender or age was not significantly associated with likelihood of discussing mental health. Social contacts who were friends or family (OR 1.17, 95%CI 0.49–2.79) were more likely than other types of relationships to be a mental health discussion partner. In addition, relationship length (OR 2.33, 95%CI 1.40–3.87) and frequency of interactions (OR 5.05, 95%CI 3.12–8.17) were positively associated with discussions of mental health.

In terms of network characteristics, social contacts with higher betweenness scores (OR 1.03, 95%CI 1.01–1.05) were more likely to be mental health discussion partners, but other network variables did not show significant associations. Two parameters, participant gender and network density, were tested in the models (model 1, model 3), but subsequently removed due to large confidence intervals resulting from small sample size at level 2 (study participants).

Table 1: Descriptive characteristics of study participants, residing rurally in the Scottish Highlands (n=20)

| Variable | Characteristic | % | Mean±SD | Missing data (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ≤20 | 5 | 51.15±0.15 | 0 |

| 21–30 | 5 | |||

| 31–40 | 20 | |||

| 41–50 | 10 | |||

| 51–60 | 20 | |||

| 61–70 | 25 | |||

| >70 | 15 | |||

| Gender (woman) | 65 | 0 | ||

| Mental health stigma | Very likely | 35 | 2.5±1.5 | 0 |

| Quite likely | 25 | |||

| Neither likely nor unlikely | 10 | |||

| Quite unlikely | 15 | |||

| Very unlikely | 15 | |||

| Wellbeing | 11.35±2.43 | 0 | ||

| Network size | 25.30±10.01 | 0 | ||

| Network density | 0.17±0.10 | 0 |

SD, standard deviation

Table 2: Descriptive characteristics of social contacts of study participants (n=505)

| Variable | Characteristic | % or mean±SD | Missing data (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health tie (yes) | 22.92 | <1 | |

| Relationship type | Family | 29.64 | 0 |

| Friend | 37.55 | ||

| Other | 32.81 | ||

| Alter age (years) | ≤20 | 2.57 | 6.12 |

| 21–30 | 8.89 | ||

| 31–40 | 17.78 | ||

| 41–50 | 12.85 | ||

| 51–60 | 21.74 | ||

| 61–70 | 18.18 | ||

| >70 | 11.86 | ||

| Alter gender (woman) | 56 | ≤1 | |

| Relationship length (years) | <1 | 6.13 | ≤1 |

| 1–2 | 10.87 | ||

| 3–5 | 21.15 | ||

| 6–10 | 6.32 | ||

| >10 | 54.94 | ||

| Proximity | Outside UK | 4.35 | <1 |

| Outside Scotland | 23.12 | ||

| >1 hour driving time (private vehicle), within Scotland | 16.80 | ||

| <1 hour driving time (private vehicle) | 18.18 | ||

| In same city/town | 33.20 | ||

| Live together | 3.36 | ||

| Talk frequency | Less than monthly | 18.77 | 0 |

| Every couple of weeks | 24.70 | ||

| Once a week | 30.43 | ||

| Most days | 17.98 | ||

| At least daily | 8.10 | ||

| Alter degree | 4.61±4.58 | 0 | |

| Alter betweenness | 8.52±48.66 | 0 |

SD, standard deviation

Table 3: Participant, social contact and relationship, and network associations with mental health discussions

| Variable | Characteristic | Model 1 Participant characteristics |

Model 2 Social contact and relationship characteristics |

Model 3 Network characteristics | Model 4 Final model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Odds ratio |

CI |

p-value | Odds ratio | CI | p-value | Odds ratio | CI | p-value | Odds ratio | CI | p-value | ||

| Predictor | Intercept | 0.30 | 0.00–66.07 | 0.661 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.02 | <0.001*** | 0.24 | 0.02–2.90 | 0.261 | 0.05 | 0.00–3.84 | 0.178 |

| Gender | 6.24 | 1.25–31.13 | 0.025* | ||||||||||

| Age category | 1.37 | 0.88–2.15 | 0.168 | ||||||||||

| Mental health stigma | 0.56 | 0.31–1.03 | 0.061 | 0.38 | 0.17–0.85 | 0.019* | |||||||

| Wellbeing | 0.90 | 0.65–1.24 | 0.520 | ||||||||||

| Proximity | 0.68 | 0.50–0.93 | 0.015* | 0.54 | 0.38–0.77 | 0.001** | |||||||

| Alter gender (woman) | 3.17 | 1.42–7.04 | 0.005** | 4.06 | 1.77–9.32 | 0.001** | |||||||

| Alter age | 0.78 | 0.60–1.02 | 0.067 | 0.71 | 0.54–0.94 | 0.017* | |||||||

| Relationship length | 2.13 | 1.31–3.47 | 0.002** | 2.33 | 1.40–3.87 | 0.001** | |||||||

| Frequency of talking | 4.96 | 3.13–7.86 | <0.001*** | 5.05 | 3.12–8.17 | <0.001*** | |||||||

| Same age | 2.02 | 0.82–4.94 | 0.124 | ||||||||||

| Same gender | 0.98 | 0.45–2.14 | 0.956 | ||||||||||

| Friend (ref: family) | 0.92 | 0.40–2.13 | 0.846 | 1.17 | 0.49–2.79 | 0.731 | |||||||

| Other relationship (ref: family) | 0.11 | 0.02–0.51 | 0.005** | 0.17 | 0.04–0.80 | 0.025* | |||||||

| Alter degree | 1.06 | 0.97–1.16 | 0.201 | ||||||||||

| Alter betweenness | 1.03 | 1.01–1.06 | 0.002** | 1.03 | 1.01–1.05 | 0.006** | |||||||

| Density | 3.17 | 0.62–16.25 | 0.166 | ||||||||||

| Network size | 0.95 | 0.88–1.04 | 0.269 | 0.94 | 0.84–1.06 | 0.299 | |||||||

| Random effect | Level 1 variance | 3.29 | 3.29 | 3.29 | 3.29 | ||||||||

| Level 2 variance | 1.49 | 6.02 | 2.67 | 5.32 | |||||||||

| Intra-class correlation | 0.31 | 0.65 | 0.45 | 0.62 | |||||||||

| N | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | |||||||||

| Observations | 505 | 467 | 505 | 467 | |||||||||

| Marginal R2 / Conditional R2 | 0.181 / 0.436 | 0.436 / 0.801 | 0.371 / 0.653 | 0.581 / 0.840 | |||||||||

| Akaike information criterion | 435.110 | 287.863 | 403.072 | 269.299 | |||||||||

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

CI, confidence interval.

Figure 1: Plots of the 20 personal networks, split across the two genders.

Figure 1: Plots of the 20 personal networks, split across the two genders.

Discussion

This study examines mental health discussions among a network sample of 505 social contacts of rural residents in Scotland. Whereas previous research tended to focus on broad measures of social integration or relationships13,14,31, or relied heavily on clinical samples17,18,32, the current study simultaneously investigates individual, relationship and network factors associated with mental health discussions. This approach offers an in-depth investigation of the complex dynamics within rural mental health networks, providing critical analysis of how informal sources of emotional support can be utilised for rural health improvement. Our study shows that rural residents demonstrate patterns of preference according to individual, relational and network properties for mental health discussion. This selective pattern potentially indicates a sophisticated approach to seeking support, highlighting the importance of certain attributes in facilitating mental health discussions.

The present study found that social contacts who were women or who were younger were more likely to be identified as a mental health discussion partner. These individuals may be seen as more understanding or supportive of mental health issues. This finding aligns with the broader literature suggesting that women are often perceived as more empathetic and open to discussing emotional issues33. Furthermore, women are often seen as primary caregivers within their social networks, which includes offering emotional and mental health support34. Consequently, social networks lacking female presence may be less effective in creating a social environment that encourages sharing of mental health issues. In terms of age, younger individuals may be more open to discussing mental health issues due to increased awareness and reduced stigma around mental health in younger generations35. A previous study found that young people, especially young women, were more likely to express empathy and provide emotional support to peers experiencing mental health issues36. This generational shift towards greater acceptance and openness can make younger individuals vital components of effective mental health support networks. Thus, the absence of younger or women contacts could exacerbate already low availability of mental health support within rural areas37.

Higher levels of mental health stigma were associated with less engagement in mental health discussions. This result, although expected, underscores the critical need to address stigma in rural areas. Prior research has shown that stigma can significantly hinder the willingness to seek help38. Reducing stigma could thus play a pivotal role in enhancing support networks, and encouraging mental health discussions can be a way to reduce the associated stigma. Stigma surrounding poor mental health remains a significant barrier to seeking help, particularly in rural communities13,39. This may not only affect individuals' willingness to discuss mental health issues, but also their overall mental health outcomes. For instance, a previous study found that stigma can lead to delays in seeking treatment, resulting in exacerbated mental health conditions40. This is especially pertinent in rural areas where access to mental health services is already limited32,41. In rural settings, where communities are often close-knit11,13,42, the fear of being labelled or judged by neighbours can be more pronounced. Previous research highlighted that the perceived judgement from others significantly contributes to reluctance in discussing mental health issues, which can lead to a lack of social support43. This lack of discussion and support is detrimental because social support is a crucial factor in managing mental health conditions6.

Longer, more established relationships, and those with greater contact frequency, were associated with a higher likelihood of mental health discussions in our study. This suggests that trust and familiarity, which develop over time and with regular contact, are crucial for such sensitive conversations. Our results are corroborated by research44 highlighting that social ties characterised by high levels of support and low levels of conflict are particularly beneficial for mental health. The authors argue that the emotional security provided by these relationships encourages open discussions about mental health, thereby facilitating early intervention and support. In rural contexts, communities often rely on a few key relationships for various forms of support, including emotional and mental health support12,45. The reliance on fewer, but stronger, social ties may intensify the role of trust and familiarity in determining whom individuals choose to discuss mental health issues with.

Contrary to a previous study on mental health discussion19, our results highlight the critical role of geographic proximity in shaping mental health discussions. Our analysis showed that relationships with geographically distant contacts were more likely to involve mental health discussions. This could indicate that people in rural areas prefer to discuss mental health issues with those who live further away, thereby providing more discretion. Previous research indicated that distance could influence social support dynamics, particularly in rural settings12,46. For instance, rural residents often prefer to seek support from non-local contacts to maintain privacy and avoid the stigma associated with mental health issues. This interpersonal distance can mitigate the social risks of disclosing private issues with others within communities. The preference for geographically distant contacts in mental health discussions also intersects with the broader literature on social network composition and mental health. For example, in another study, both the quantity of social connections and perceptions of community cohesion were moderately associated with mental wellbeing in rural and resource-poor localities, as these might provide diverse sources of support, and reduce the reliance on local contacts who might be less understanding or more judgemental47.

We also found that betweenness centrality was a significant predictor of mental health discussion, whereas other network characteristics like degree and network size were not. Individuals who bridge unconnected parts of the network appear to be crucial for mental health discussions. Sensitivity analyses confirmed that this effect was not simply due to them being a partner or spouse, highlighting the unique role of betweenness in facilitating mental health discussion. This finding aligns with research on the importance of network centrality and bridging roles in providing social support more broadly48. These bridging individuals are likely perceived as trustworthy and central to the network, and therefore may be useful to include in rural health improvement efforts.

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations of the present study should be highlighted. The study focuses on a single area of Scotland, which limits generalisability to broader geographies. In addition, our multi-level models included a relatively small sample size at level 2 (eg study participants), which restricted the number of participant and network characteristics we could test. Future research would benefit from including diverse rural geographies, and larger sample sizes in order to validate and expand upon our findings. In addition, our variable, and therefore definition of mental health discussion, included a narrow focus on going to therapy or receiving a diagnosis. More subtle discussions of mental health were not captured in the data, and future research should aim to measure a continuum of mental health discussion or order to broaden understanding. Similarly, our study did not assess whether a social contact shared mental health information with a participant, precluding an assessment of mental health reciprocity, an area for future research to explore. Lastly, our measure of mental health stigma, although frequently used23, consisted of a single item, and future research should aim to include more comprehensive scales of stigma.

Conclusion

This study offers a first glimpse into the types of relationships and social networks that foster mental health discussions in rural areas. It demonstrates that personal attributes, relational characteristics and network properties can all affect the likelihood of mental health discussions. As such, the study highlights multiple, tenable points for rural health intervention, including the promotion of frequent contact, mixed age and gender social networks, and reductions in mental health stigma.

Funding

We acknowledge funding from the Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00022/3; MR/S015078/1), and Chief Scientist Office (SPHSU18).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

You might also be interested in:

2022 - Primary health care in the Amazon and its potential impact on health inequities: a scoping review

2008 - Improving trauma care in rural Iran by training existing treatment chains