Introduction

The role of pharmacists and pharmacies as an integral part of the healthcare system is well known and widely accepted as essential in Australia1,2. This recognition includes providing access to scheduled medications and over-the-counter therapeutic products and advice. Typically, only pharmacists or companies of pharmacists are permitted to own and operate pharmacy proprietary businesses in the community, and a similar concept of legal liability (without pecuniary interest) applies to directors or managers of hospital pharmacies3,4. Therefore, a workforce of practising pharmacists is crucial to the operation and viability of the entire pharmacy sector, especially in rural and regional Australia. However, similarly to many allied health professions, there is a lack of practising pharmacists across rural and remote Australia5-7. Like other areas of the rural workforce, there are many challenges for staff recruitment and retention7-9. These shortages of rural pharmacists may impact fair and equitable access to medicines, primary healthcare advice and over-the-counter medicinal products10,11.

Research into rural health workforce since the year 2000, particularly among pharmacy-focused literature, typically investigates why pharmacy students, interns and qualified pharmacists are reluctant to work in regional and rural settings. Relatively few studies focus on an employers’ point of view7-9,12-20. This study undertakes a dedicated exploration into employers’ perceptions of the extent and nature of the barriers involved in rural recruitment, and the efforts employers have made to address these. Specifically, this study aims to explore employers’ perspectives of (1) recruitment and retention of staff pharmacists in their regional or rural practices and (2) strategies to mitigate recruitment and retention challenges of regional and rural staff pharmacists.

Methods

Study design

This study was designed as a qualitative, cross-sectional, exploratory study. As an exploratory study to address a void in the literature, inductive content analysis based on semi-structured, face-to-face interviews was used in line with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist21.

The researchers

A male-identifying pharmacist aged 39 years from an ethnic and linguistically diverse background, and also an early-career researcher, led the research. This researcher was also practising in a clinical capacity in a Victorian regional centre at the time of the study and might have been known to some of the potential participants. A female-identifying researcher who was not a pharmacist, but experienced in qualitative research and social sciences, provided training in interviewing and data analysis but was not directly involved in interviewing. This researcher reviewed the transcripts and coding so both researchers engaged in critical discussion of the meaning of the data.

The sample

A randomised sample was drawn from pharmacy business proprietors and/or managers of pharmacy practices in the North-Central and Murray regions in the state of Victoria, from east of Wangaratta to Swan Hill and Ballarat.

The sampling strategy was based on a purposive random concept, in order to obtain an increased impartiality and credibility of results22,23. As a rural pharmacist, the primary researcher may have known or known of some of these employers; random selection removed any influence of this. A total of 151 unique pharmacy employers were identified in the region using publicly available sources, including the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) register of practitioners, Victorian Pharmacy Authority, HealthDirect Australia and Google. All 151 were entered into a database and randomised using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v28 (IBM Corp; https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics) to select a sample of 20 participants. Invitations to participate, along with plain language statements and consent forms, were then individually addressed and sent by e-mail to each potential participant. Duplicated entries of pharmacy practice entities (see inclusion criteria below) and those who refused to participate in the study were replaced by further randomisation and selection from the same pool of pharmacy employers, until a total sample size of 20 was reached. This number was based on the principles by Braun and Clarke (2013), where ‘a sample size of between 15 and 30 individual interviews tends to be common in research which aims to identify patterns across data’24, without the need to ascertain data saturation or the lack thereof25.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for potential participants were as follows:

- Person must be a registered pharmacist under the definition by AHPRA.

- Person must be aged 18 years or older at the time of consent.

- Person must be a proprietor (or a representative), a manager or operator (however titled), or a person with the authority to recruit and employ pharmacists, for a pharmacy business or operation at the time of consent and interview.

- If the same person(s) own, manage or operate multiple pharmacy practices in the database, those entries will only be counted as a single data point.

- The physical location of the pharmacy practice must be in regional or rural Victoria, as defined by Modified Monash Model category MM 2 or greater26.

- Person consented to participate in this study.

Data collection

The data collection period ran from March 2022 to July 2022. The interviewer contacted each pharmacist by telephone to arrange a suitable time for an interview, often after business hours. The interviewer travelled to the location of each pharmacist to conduct interviews, usually in the pharmacy. The face-to-face interviews were conducted by the interviewer (also a practising pharmacist) using a standard set of questions (see Appendix I), but the interviewees were allowed to speak freely without any prior leading codes or themes. They were not interrupted in any of their responses until they reached natural conclusions as dictated by the interviewees themselves. There was no set time limit, but the interviews were expected to be between 20 and 60 minutes. Each interview was audio-recorded with permission of the participant, and written notes were also recorded.

Data analysis

The audio recordings of each interview (n=20) were transcribed by an external transcription service into 20 text documents. Each document was checked with the recording and interviewer notes, and then de-identified for analysis. Transcripts were not returned to participants because they were busy business operators, and repeated access would be unduly onerous. As an exploratory study, a content analysis of responses was undertaken inductively without a pre-determined code book27. The content analysis was performed by the primary researcher on each of the 20 documents in the following steps28,29. A total of 473 responses to key issues about recruitment and retention were coded into 113 codes using an inductive coding process. After review of these codes with the second researcher, similar codes across all questions were grouped and then codes that were overlapping or closely related were combined. Critical discussion led to condensing negative and positive responses of the same issues, as well as condensing some codes that were repetitive. Codes were not condensed where the data reflected different issues, or if the pharmacy knowledge of the primary researcher articulated differences. This reduced the number of codes to 72. The codes were then grouped into three major topics: remuneration, work conditions and policy aspects; workplace and role satisfaction; and social factors. The findings were presented around these three topics, with detail about the responses in tables. Given the large number of codes, findings within each of the three topics are grouped by the challenges faced by employer pharmacists, subsequent issues resulting from the challenges of recruitment, and the participants’ strategies to mitigate workforce challenges. For each code, the frequency of response is also provided in tabulated form. To preserve anonymity, the characteristics of participants were not identified, but the findings draw on quotes from all participants. The terms ‘employers’ and ‘participants’ are used interchangeably.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Melbourne (project ID: 24626).

Results

The sample

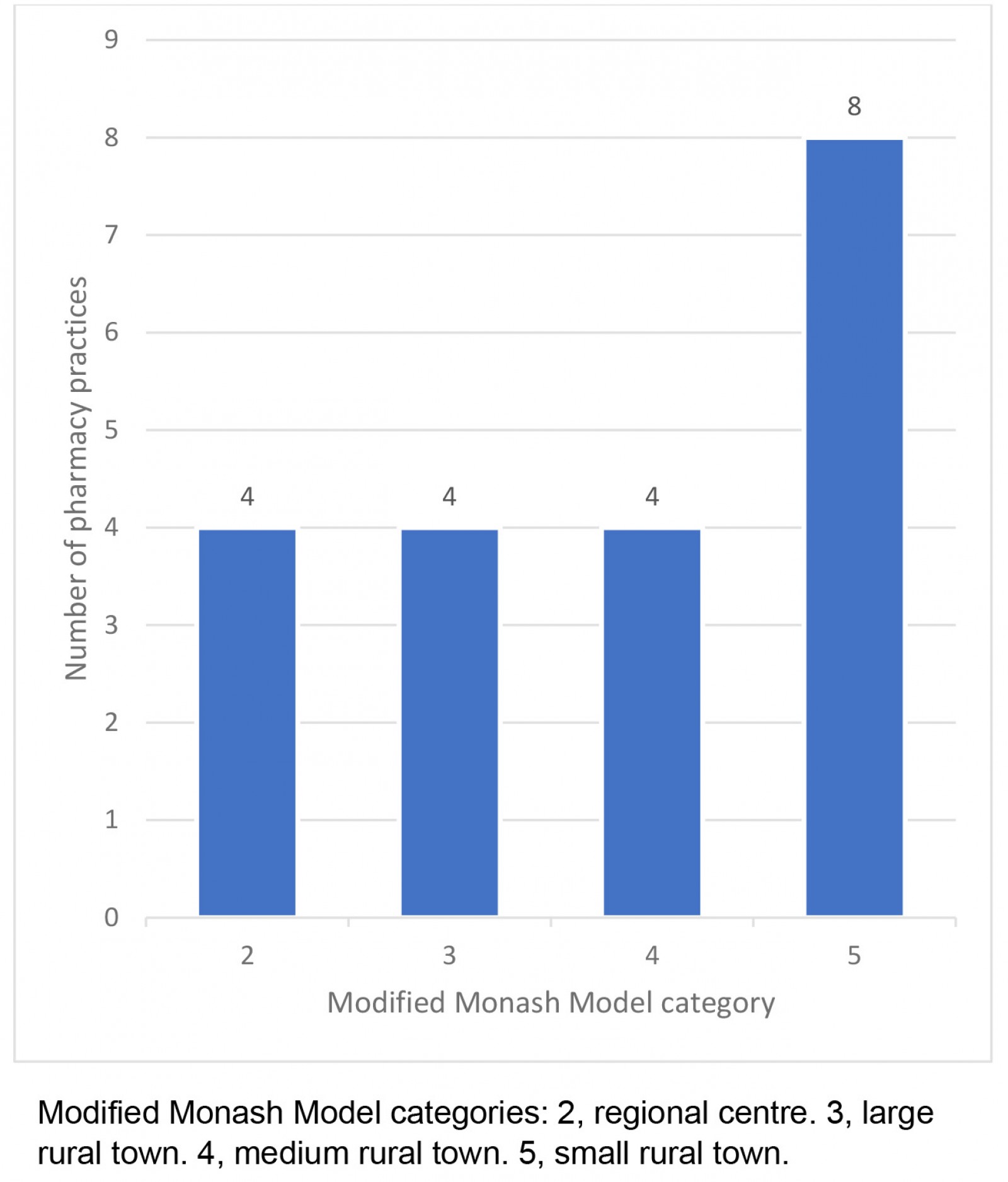

The participants were based in regions along the Murray River, Goulburn Valley, Grampians and North-Central Victoria. More than half (n=12) were classified as ‘medium rural towns’ or ‘small rural towns’ according to the Modified Monash Model categories (Fig1)26. Over a quarter (n=6) were best described as single-pharmacist pharmacies, whereby typically only one equivalent full-time pharmacist was on duty on any given day. Four potential participants refused to be enrolled, all of whom cited time pressures as the main reason. These pharmacists included individuals with multiple roles in the practice, such as pharmacist-manager or pharmacist-proprietor.

Discussion here is focused on three major topics identified by employers about recruiting and retaining a rural pharmacy workforce: remuneration, work conditions and policy aspects; workplace and role satisfaction; and social factors.

Figure 1: Number of pharmacy practices included in study, by rurality (Modified Monash Model).

Figure 1: Number of pharmacy practices included in study, by rurality (Modified Monash Model).

Remuneration, work conditions and policy aspects

Issues surrounding remuneration, work conditions and policy-related matters were identified as some of the greatest challenges to pharmacy employers (Table 1). The most frequent challenges discussed by participants were the high cost of recruitment and use of locum staff (n=7). These pharmacy business operators stated they preferred not to use recruitment and locum agencies, citing prohibitive cost and lack of long-term outcomes. One pharmacy owner described the expense of recruiting a locum pharmacist via an agency: ‘… $30,000, and they [pharmacists] may not even be there for six months ...’ The impact of not recruiting permanent staff was said to result in the use of short-term staff and reshuffling existing pharmacy staff to meet rostering needs.

When asked about their strategies to address staffing, all 18 employer pharmacists currently recruiting indicated they were either paying or were prepared to pay above the hourly rate as described in the Pharmacy Industry Award (Table 1). Some (n=4) went on to describe the current PIA hourly rates of pay and conditions as ‘terrible’, ‘embarrassing’, an ‘absolute disgrace’, ‘simply too low’ and ‘insulting’. A quarter (n=5) also believed that inadequate pay, conditions and career prospect were deterring aspiring people (mostly school-leavers) from becoming undergraduate students of pharmacy, and subsequently entering the profession as pharmacists. Over half of the participants (n=11) believed that, in addition to paying above the Pharmacy Industry Award on a case-by-case basis, having access to qualification programs in rural or regional areas (with or without bonded scholarships) was the next best strategy in recruiting and retaining pharmacist workforce in their locale. However, they also understood the reality of significant delays between implementation and those graduates becoming available staff, as pharmacist qualifications programs were at least 2.5 years in duration for post-graduate candidates, plus a minimum of 1 year of compulsory internship in Australia at the time of interview. Half of the pharmacy practices that were seeking to employ a pharmacist (n=9) expressed that one of the strategies to attract prospective employee pharmacists was the promise of future business partnerships, either in part or whole. One pharmacy owner described the strategy as follows:

… being hired onto this [pharmacist] team, partnership opportunities is one thing that is a huge incentive for a lot of pharmacists along with a higher than standard [Award] level of pay.

However, nearly half of those willing to offer partnerships (n=4) also recognised that there was significant financial barrier for early-career pharmacists to enter business ownership or partnership due to increasing initial capital outlay and investment, particularly in recent years. They also predicted that it may become a generational issue for businesses in the sector, when older pharmacy business owners choose to retire and attempt to sell their practices. Clearly, employer pharmacists have concerns about their business costs and the lack of a sustainable workforce, thereby threatening the continuity of the pharmacy sector in rural and regional areas.

Table 1: Pharmacist remuneration, work conditions and policy aspects – topics, findings and study participant key quotes

| Topic | Findings | Example(s) of key original quotes |

Total (n=20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Challenges | Pharmacist recruitment and locum agencies (in professional communities) are prohibitively expensive, and long-term retention/recruitment results/outcome uncertain |

‘Appalling. So we have been looking for a full time pharmacist for ... three months ... and not had one single 'bite'.’ ‘Extremely thin, very difficult to find pharmacists regionally, especially in a small town like where I am, so yeah, extremely tough market.’ |

7 |

| Shortage of pharmacists and applicants for permanent roles |

‘So, pharmacist manager ... advertised probably last year (2021) around June and then we got a candidate ... around September ...’ ‘... but I have heard that there’s 180 – from other people, 180 pharmacist positions on Seek and no one can get reliable pharmacists.’ |

5 |

|

| Lack of employee pharmacists and/or diminishing pool of applicants, due to pharmacists leaving the community pharmacy sector or the professional altogether, resulting in shrinking pool of potential applicants (+/- lack of policy action) |

5 |

||

| Regional pharmacy school closure (especially Charles Sturt University Wagga Wagga campus) resulted in decreased number of students, interns and pharmacist applicants | ‘... obviously the schools started closing down. In Wagga, ... that school we were just getting interns or getting pharmacy students and they were coming through, but then once they started closing that down, we just started struggling to find a pharmacist.’ |

5 |

|

| Inadequate pay, conditions and career prospects preventing quality individuals from becoming students and entering the profession, and/or to apply for employment |

‘I think the biggest barrier to pharmacy is recruitment and that’s reflected in the wages and the – you know, the [pharmacy] Guild and all the Guild-Government agreement, or whatever, has just done such a disservice to pharmacies and pharmacists, and is just ruining our profession and it’s heartbreaking.’ ‘... there’s always a bit of a negative stigma towards the pay for being a pharmacist, it’s the lowest paid profession as a graduate perspective out of any profession.’ |

5 |

|

| Prevailing Pharmacy Industry Award remuneration and conditions being inadequate, and described as ‘terrible’, ‘embarrassing’, ‘absolute disgrace’, ‘simply too low’, ‘insulting’ |

‘... all our staff get above award wages because we just feel embarrassed to pay what is Award [rates] because we expect a lot of our staff.’ ‘I think to me as an employer I even find the Award rate was quite insulting.’ ‘... nobody works for Award [rates], that's just terrible.’ ‘... the biggest issue is the – I think is the Award wages for pharmacists is an absolute disgrace and that needs to be factored into a Guild-Government agreement, to make it viable.’ |

4 |

|

| Significant financial barrier for early-career pharmacists to enter business ownership/partnership in recent years may become a generational issue for business continuity |

4 |

||

| Immigration policy change/de-listing from Skills Priority List resulted in fewer international applicant(s) |

2 |

||

| More hours and higher wages may be barriers to retention in smaller, rural pharmacies |

2 |

||

| Impact | Using fixed-term contracted or locum pharmacists to cover rostering while searching for permanent staff |

‘Out of necessity I've interacted with about four or five locum pharmacists over the last four months to fill roles on a casual basis ...’ ‘In the past 12 months probably three times to hire and then additional times to try and source locum pharmacist, so try and source someone for ongoing employment three times and yeah, locums another two or three times as well.’ |

6 |

| Reshuffling existing staff pharmacists within the organisation to cover local rostering needs |

5 |

||

| Staff members to work in different locations and/or sharing professional responsibilities |

3 |

||

| Risk of communities losing or having reduced access to local pharmacy business presence due to lack of staff pharmacist (especially on weekends and public holidays), or reduction of overall business hours to accommodate individual staff pharmacists |

3 |

||

| Strategies | Offering/paying above Pharmacy Industry Award remuneration |

‘... yeah definitely all of my staff get paid above the award wage.’ ‘... I don't feel that the remuneration has kept at pace. Certainly the award, nobody works for award ... ’ ‘Yeah, so we certainly offer well above award wages.’ |

18 |

| Need for regional or rural pharmacist qualification programs, +/- bonded scholarships (noting significant time delay between implementation and staff availability) | ‘ ... so maybe rural scholarships for students that live [locally].’ |

11 |

|

| Professional networking, such as ‘word-of-mouth’ recruitment and opportunistic hires for both permanent or locum roles |

10 |

||

| Potential or likely future business partnership or full ownership as an incentive in staff retention |

9 |

||

| Support for visa applications for pharmacists of overseas origin, +/- rurally or regionally bonded immigration policy or quota for international candidates |

8 |

||

| Encouraging interns/newly qualified/early career pharmacists to apply for position(s) |

7 |

||

| Support (especially financial) for relocation and/or travel to workplace |

7 |

||

| Support for accommodation (short-term or permanent) |

7 |

||

| Technology-based solutions, such as rural- or regional-specific recruitment websites/software applications may be beneficial due to transparency of geography, and bidirectional satisfaction ratings system |

7 |

||

| Less competition (eg from hospital pharmacy sector) for available pool of applicants, especially when it appears to shrinking, and lowering of overall professional expectations of prospective candidates to remain at basic/minimum level in order to maximise recruitment pool |

6 |

||

| Tangible key performance indicator based financial incentive and/or financial incentive for on-going employment (eg retention bonus) |

5 |

||

| Incentivising local school students of regional/rural origin by offering scholarships to study pharmacy qualification programs |

5 |

||

| Federal and state government policy and legislative reform, such as contribution to, and improvement of, reasonable access to housing and related infrastructure in rural and regional areas; and public-funded employment services/agency for permanent and locum pharmacists for immediate and medium-term relief of staffing shortage |

5 |

||

| Support for non-clinical tasks (eg marketing, information technology), thus freeing up pharmacist time for professional services |

3 |

||

| Tertiary educational program reform for urban-based students, such as rotational internship to rural/regional pharmacy practices |

3 |

Workplace and role satisfaction

Of the employers looking to recruit, all but one (n=17) discussed varying degrees of difficulties in recruiting staff pharmacists at any equivalent full-time fraction (Table 2). While some were more concerned than others, most (n=17) used emotive language to describe their perception of the market to employ staff pharmacists: ‘very hard’, ‘terrible’, ‘appalling’ and ‘diabolical’. A majority (n=14) also expressed frustration over the length of time for recruitment. Further, respondents also talked about the number of applications tending to be very small, and three respondents indicated that they sometimes received no applications at all for up to 12 months after initial advertising.

In discussion of the nature of these roles at these rural and regional pharmacies, more than half of respondents (n=11) reported that their advertised positions were full time or ‘up to full time’, or ‘flexible’ where the prospective employers were prepared to take any time fraction that the applicants would offer (Table 2). One pharmacy owner described an example of flexible working hours:

… we have another pharmacist who lives in a town about half an hour away and she’s part time … has young children … leaves early to pick them up from … after school.

Interviewees were open to negotiations in terms of days, time and duration of shifts that the applicants were willing to take. In terms of rostering, more than half of the employers (n=11) indicated that no weekend work was expected of their employees, and nearly all (n=17) denied any expectation of ‘on-call’ (on-demand availability outside of ordinary working hours for work-related activities) services from their staff. Some (n=5) went on to discuss a vicious cycle of staff attrition due to workload and the lack of opportunity to rest, exacerbated by lack of staff to fill rostering needs. A majority of the employers (n=13) indicated that preparations for dosing administration aids such as Webster-pak were expected to be part of the role of any prospective employee. Some employers indicated that there was an expectation of employee pharmacist involvement in opioid pharmacotherapy/opioid replacement therapy (n=8) while others did not (n=8).

The most common strategy to increase the attractiveness of these roles was to retain their existing experienced staff members, typically for durations of greater than 12 months, and a large number (n=13) were successful in achieving that goal (Table 2). The next most effective strategy, as perceived by employers, was the promotion of work satisfaction and the use of positive reinforcement (n=11), which involved the use of positive language and feedback at regular intervals. The next most common strategies were efforts to create and promote harmonious and relaxing work environments (n=7), and encouragement of employee professional growth by supporting upskilling and training (n=8), often by either flexibility in rostering and paid hours, sometimes with direct financial subsidy to cover cost of activities (n=3). Employer pharmacists recognised the need to be flexible and to provide a supportive working environment.

Table 2: Pharmacist workplace and role satisfaction – topics, findings and study participant key quotes

| Topic | Findings | Example(s) of key original quotes |

Total (n=20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Challenges | Very difficult to find permanent (full- or part-time) pharmacists | (see Table 1) |

17 |

| Employers describing the difficulties in recruitment as ‘very hard’, ‘terrible’, ‘appalling’, ‘very limited’, ‘extremely thing’, ‘very poor’, ‘fairly wild’, ‘pretty tight’ and ‘diabolical’ | (see Table 1) |

17 |

|

| Long delay between advertising and receipt of application(s), and often in small numbers |

‘We’ve had the ads running nonstop for well over 12 months now.’ ‘Yeah, we advertised on Seek but got zero bites. The wage was pretty good, it was, like, 45 an hour. Yeah, but still didn’t get any traction, then. Not even really enquiries ... ’ |

14 |

|

| Lack of access to face-to-face continual professional development and networking opportunities |

6 |

||

| Staff attrition due to workload, lack of opportunity to rotate/rest, and stress |

5 |

||

| No application received for advertised positions (for up to 12 months since initial advertisement) |

3 |

||

| Excessive/unmanageable workloads as a barrier to rural/regional practice |

3 |

||

| Repetition or monotony of work, especially in small, single-pharmacy towns may not be appealing to younger/graduate pharmacists |

2 |

||

| Deterioration and/or lack of appreciation in consumer habit and attitude towards to pharmacists and employees in community pharmacy |

2 |

||

| Nature of roles | No on-call services expected of employee |

17 |

|

| Responsibility in residential medication management and Webster-pak |

13 |

||

| Full time (including ‘up to full time’ or ‘flexible’) position(s) advertised |

11 |

||

| Weekend work expected |

11 |

||

| Weekend work not expected |

9 |

||

| Pharmacotherapy/opioid replacement program expected |

8 |

||

| No pharmacotherapy/opioid replacement program | ‘ ... opioid replacement is definitely a barrier. Even my current pharmacists don’t feel comfortable doing it and in a small town ... ’ |

8 |

|

| Part-time position(s) advertised |

5 |

||

| Few or no staged-supply involvement |

3 |

||

| Customer/patient-focused pharmacists tend to favour community pharmacies and, therefore, more likely to work and remain in that sector |

3 |

||

| Some staged supply involvement |

2 |

||

| No responsibility in residential medication management and Webster-pak |

2 |

||

| Strategies | Greater than 12 months of (at least one) pharmacist retention |

‘ ... she worked up long service leave, coming in every day for 10 years. I think she’s now up to close to 25 years. So you do build relationships with people and I think professionally, it’s very rewarding.’ ‘[name of pharmacist] was [working here for] 11 years. ... he was a student ... and then he did his internship here and stayed on.’ |

13 |

| Promoting work satisfaction and positive reinforcement |

11 |

||

| Flexibility in scope of practice and/or professional responsibilities |

9 |

||

| Support for training and upskilling |

8 |

||

| Creating a relaxed/harmonious working environment |

7 |

||

| Professional support from other pharmacists in the pharmacy/business group |

6 |

||

| Access to continuing professional development opportunities no longer a barrier due to virtual availability online |

5 |

||

| Financial support for the attendance of continuing professional development events |

3 |

||

| Positive feedback or encouragement for staff members are beneficial to workforce retention |

3 |

||

| Manageable/favourable workloads |

3 |

Social factors

A majority of prospective employers (n=14) recognised the single biggest challenge in terms of recruiting pharmacists was geographical distance from metropolitan areas, compounded by actual or perceived social isolation (Table 3). One pharmacy owner described the phenomenon of isolation as follows:

Yeah, I think the main challenge from [social isolation] … [the feeling] like you’re picking up and you’re leaving your life … community and you’re moving to the more alien place. You’ve got to start from scratch and … your friends… [sic] is not there.

A few participants (n=3) identified that long, extended hours of work are detrimental to family life and leisure activities, and the same number (n=3) expressed similar concerns for weekend rostered shifts. A few (n=3) also believed that lack of access to cultural and/or religious practice opportunities and venues might be barriers.

A key strategy for many participants (n=16) was to mitigate most of those challenges was to be flexible in terms of working hours, in order to accommodate the prospective employees’ family responsibilities and social commitments (Table 3). A pharmacy employer considered this also being part of the ‘positive work culture’, saying:

I think positive work culture is a big thing. Being flexible with rostering and … understanding … the things that happen in people's lives where they need to take time off work or reschedule things with other pharmacists that I work with.

Lifestyle attractions and recreational activities in some regions were also heavily promoted by nearly half of the prospective employers (n=9). Nearly half (n=8) of the participants identified that, especially in terms of staff retention, it might be helpful to enhance personal and family connections of the employee to the local region. In two cases, employers either directly hired the employee’s spouse into the organisation in a non-pharmacist, non-clinical role, or helped the partner find employment locally. In terms of personal satisfaction, some participants (n=7) indicated that the friendliness and rapport with the local clientele, followed closely (n=6) by family-friendliness of the locale (eg access to schools, perceived safety for young families and community sporting engagements) also serve as attractions for prospective employees. Some participants (n=4) even offered direct subsidies for social or leisure activities, such as gym memberships. Employer pharmacists seemed to be aware of the social aspects of living and working regionally and rurally.

Table 3: Pharmacist social factors – topics, findings and study participant key quotes

| Topic | Findings | Example(s) of key original quotes |

Total (n=20) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Challenges | Challenges of geographical distance from metropolitan areas and social isolation |

‘But our location ... it’s not a city and a lot of people don’t want to come out of the city. So geographical isolation is a big probably part of if I did recruit.’ ‘I know that in the past when we have had people who have come from Melbourne to work that they have felt a little bit isolated from their family and not necessarily had the cultural opportunities in our town that they would have had in their hometown.’ |

14 |

|

| Extended hours of work not compatible with family/leisure commitments |

3 |

|||

| Weekend work as an impediment to family or social life |

3 |

|||

| Lack of access to cultural/religious practice venues and/or activities |

3 |

|||

| Lack of access to school, social and (non-sporting) recreational activities, or spousal employment/career opportunities |

3 |

|||

| Lack of cultural and/or religious inclusivity, understanding and acceptance by local populace |

2 |

|||

| Strategies | Flexible and/or family-friendly hours of work |

‘So it was that flexibility which is key to keeping them happy.’ ‘ ... I’m the type of employer that’s very flexible, and very considerate of the employee pharmacist ... because you want to make sure they’re happy in their role, they want to come to work ... ’ |

16 |

|

| Lifestyle attractions/recreation of locale and/or surrounding regions (eg fine dining, tourist attractions) | ‘Well, the area has got a good lifestyle, because you’ve got very beautiful communities around – like [names of surrounding townships] so if you like wines, and food, and – there’s a lot of – it’s very family friendly, and it’s a very safe area.’ |

9 |

||

| Personal, family connections to locale (eg spouse, children, extended family and social network) help with employee retention |

8 |

|||

| Friendliness/rapport with local clientele and community |

7 |

|||

| Family-friendly locale (eg access to schools, perceived safety, community sport and social activities for children and adolescents) |

6 |

|||

| Support for social/leisure activities (eg subsidised gym membership) |

4 |

|||

| Ease of access/transportation to and from locale |

3 |

|||

Discussion

The most significant finding in this study centres around remuneration and working conditions for employees. Employers are broadly in agreement with prospective employees in terms of the inadequacy of the prevailing Pharmacy Industry Award7,14,16,18,20 as it has been outstripped by rising cost of living in recent decades and has failed to keep in pace with other sectors in the industry – such as public hospital enterprise bargaining agreements. All of those currently recruiting or planning to recruit indicated that they are either already paying hourly rates above the Pharmacy Industry Award, or were planning to do so. Moreover, one of the flow-on effects of the pay and conditions being low in the industry award is that it may make the career pathway of being an employee pharmacist less appealing16,30,31 and, according to some employers, less attractive than other high-paying health professions.

Apart from direct pay and wage increase, other financial incentives, such as promised or planned pecuniary partnerships in the pharmacy business, were mentioned by nearly half of the participants. While a large proportion of the available literature also directly mentions or indirectly implies ‘financial incentives’ in general terms14,16,18,20, only a small number specifically mention ownership, including an international source7. Other than the obvious financial reward in (part or full) proprietorship, this strategy was also considered to part of long-term succession planning whereby the continuity of the practice would be guaranteed by renewed workforce ownership. However, some of those who were partial to this strategy also acknowledged that, given the ever-increasing amount of capital required for purchase of both the assets and goodwill of the businesses, it might become an increasing barrier to early-career and prospective proprietors. Thus, it may limit or negate its usefulness as an incentive for pharmacists who might otherwise be willing to practise in regional and rural areas.

While many employers indicated varying degrees of difficulties in recruitment of permanent staff, the reasons appeared to be multifactorial. A key challenge was the professional role itself. A large number of the roles consistently required pharmacists to perform ‘standard duties,’ such as dispensary services and procedural work associated with dosing administration aids, including Webster-pak and pre-packed sachets. Some employers conceded that this may translate to a feeling of repetition of tasks and monotony of work, which appeared to mirror the sentiments of some existing literature8,12,18. Some of those offered to directly fund staff upskilling and training for qualifications required for those extended roles, provided that the training served functions that aligned with the scope and value of the business practice. There does not appear to be a significant amount of existing literature to ascertain the effectiveness of this strategy.

Some participants identified stress-related challenges such as staff requiring frequent ‘sick leave’ days, leaving the job or even abandoning the profession altogether, due to lack of rostered days off or rotation and stress, or sheer workload-related stress. Although a number of participants indicated that these were likely to have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, others argued that this preceded recent events. Therefore, some participants attempted to mitigate those challenges by creating and promoting positivity in the work environment, thus translating to a relaxed and harmonious workplace among staff members. Whilst the workload might fluctuate given the unpredictable nature of employee–client context, these employers’ efforts focused on fostering a positive employer–employee relationship. Some participants used explicit examples of technique, such as positive feedback on the outcome of an employee pharmacist’s work, or reinforcement of their professional achievement in general. Overall, the key outcome that these employers were aiming to achieve, in order to mitigate the impact of recruitment challenges on their practices, was long-term staff retention. Using some of the aforementioned strategies, a majority of the participants were able to retain at least one staff pharmacist for more than 12 months, which reduced the number of times positions needed to be advertised and their length of time remaining vacant. These strategies do not appear to have been studied or documented quantitatively in existing literature.

Another major topic identified in this study was the participants’ perspective and mitigating strategies of social factors that influence prospective employees. While the majority of participants recognised the obvious key challenge of geographical and associated social isolation, a number of nuanced barriers were also identified by different groups of employers. For example, work hours were inherently considered to be barriers to family and social life, especially if they are long and/or if they occupied the employees’ weekend or public holidays. Most employers attempted to overcome this challenge by offering flexible or family-friendly hours, such as shorter shifts or time allowance to accommodate childcare needs (eg school drop-off and pick-ups), both of which were critical in a profession heavily dominated by women with a comparatively large share of family responsibilities32.

Many participants exhibited at least some degree of ‘localism’, supporting school-leavers and undergraduate students of rural and regional origins. These strategies included incentivising students using some form of public funding, such as scholarships and bursaries, to study and work in rural and regional areas beyond graduation, as well as private funding directly from the businesses to secondary school students. However, the most recent literature appears to suggest that these may not be the most impactful strategies for retention of the pharmacist workforce in underserved areas of Australia6,15.

Some participants recognised another challenge presented by small, rural or regional populations as the relative lack of access to cultural and religious practices, such as dedicated festivals and venues (eg mosques or temples). This, according to a different group of participants, might also be compounded by the fact that such locales are typically dominated by relatively insular Anglo-Celtic populations, and thus the non-acceptance of cultural and/or religious minorities might negatively impact the emotional wellbeing of modern, multicultural employee pharmacists33,34. Those participants indicated that, if their locations were in reasonable proximity to a regional population centre or large cities, these issues might be partially mitigated by those employees’ ability to travel to their preferred venues of religious or cultural observance. However, there does not appear to be an established strategy to overcome this issue particularly in small rural towns26. The general consensus among those participants was that local and/or state governments should take responsibility to invest in solutions locally in the future.

There were a range of comments about the impact of COVID-19 on the rural pharmacy workforce, including that the pandemic had exacerbated the rural workforce shortages, required increase remuneration for employees, and added stress and financial pressures to employer pharmacists. Shortly after commencing data collection, on 26 April 2023, the 60-day dispensing announcement was made by the Australian Government35. This was clearly on the minds of some interviewees, who felt that this would negatively impact them financially and that rural subsidies were needed to ensure a future rural pharmacy workforce.

It is clear that urgent action is required to address these industry-wide issues collectively, in order to secure a viable rural pharmacist workforce in the future. Workplace-related stressors, such as long or extended work hours and lack of rest, appear to be shared across the sector. Therefore, appropriate amendments to protect the wellbeing of employee pharmacists in future awards, possibly as part of the ongoing Community Pharmacy Agreement, must be considered as a rural workforce strategy.

A limitation to this study was its restriction to one part of Victoria, so it is unlikely to be generalisable to other areas of Australia. The data yielded in this study do not relate to remote locations. Also, the sample is small. However, the sample was randomised, and the data collection was conducted using face-to-face interviews. Being a qualitative study with a focus to address an already well-quantified issue, it offered unique insights to a perspective that has appeared to be underexplored.

Conclusion

This study identified three major topics from an employers’ perspective in terms of the challenges they face in recruitment and retention of pharmacists in regional or rural Victoria, and their efforts in mitigating them: remuneration, work conditions and policy aspects; workplace and role satisfaction; and social factors. All prospective employers agree that the prevailing pharmacy pay levels are an impediment to attracting and retaining an effective workforce to regional and rural Victoria in sufficient numbers and, to overcome this, they have agreed to pay above the award rates. Employers and employees also appear to share concerns regarding social and workplace-related factors, such as geographical isolation and the need for a flexible and harmonious work environment.

Acknowledgements

The authors are sincerely grateful to the Melbourne University ethics committee, and all participants who contributed to this study. This study was supported by the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training program and the Rural Pharmacy Liaison Officer Program.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.