Introduction

Relocation of older individuals has been associated with adverse outcomes, including physical and cognitive decline and reduced wellbeing1,2. Deterioration of chronic conditions and serious acute illnesses are major factors preventing older individuals from remaining in their accustomed communities3. For older island residents, these factors can be reasons for relocation through non-returned referrals from their familiar islands. Although the frequency of all off-island referrals was reported4, no studies to date have analyzed the breakdown or frequency of off-island referrals that prevent older island residents from remaining on their original islands.

Polypharmacy is associated with various adverse health events and commonly defined as the use of five or more medications, although no universal definition exists5. Previous studies have reported that polypharmacy is linked to various health events, including fall6, hospitalization, and mortality7. However, no previous studies have investigated the association between polypharmacy and off-island referrals that prevent older island residents from remaining on their islands.

This study aimed to describe the cases of non-returned off-island referrals and to examine the relationship between polypharmacy and non-returned off-island referrals in the primary care setting of remote islands.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study in Okinawa, Japan, following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines8 (Appendix I). This study was conducted using the Okinawa Remote Islands Cohort (ORIC), a multicenter historical cohort designed to investigate multiple outcomes. The ORIC was established to clarify the characteristics of off-island referrals to the remote islands of Okinawa and to identify the risk factors associated with these referrals.

Study participants and setting

Okinawa Prefecture comprises a large main island at the southernmost tip of Japan and several smaller surrounding islands. Okinawa Prefecture, which has the second-largest number of inhabited islands among Japan's 47 prefectures9, is a suitable location for research on remote island health care. Within the 47 inhabited islands of Okinawa10, this survey covered 14 outpatient clinics across 13 islands. These 14 remote island clinics operate under a unified scheme and are managed by the same prefectural parent organizations. The population of each island ranges from 234 to 244411. All the islands had only one clinic; however, Iriomote Island, the most populous island, had two clinics.

These clinics lack inpatient facilities, and no hospitals or pharmacies are present on the remote islands. Several of the 13 islands host nursing homes for older residents; however, these non-medical institutions are unequipped to deliver advanced medical care.

These clinics are staffed by one doctor, one or two nurses, and one or two medical assistants, but no pharmacists. Although many physicians and nurses are temporary workers from outside the islands, medical assistants are island residents and often know most older island residents. Most physicians assigned to these remote clinics are dispatched after completing specialized training for solo medical practice on the islands12. They provide daily outpatient care on weekdays and 24-hour, 7-day emergency care. These clinics have X-rays, electrocardiograms, ultrasound, basic blood tests, and microscopy but lack CT, MRI, endoscopes, and major surgical equipment. Patients requiring specialist consultation or inpatient care are referred to off-island medical facilities. For non-urgent referrals, patients use regular ferries, high-speed boats, or aeroplanes, while emergency transfers are conducted by helicopters operated by air ambulance services or by the Self-Defense Forces or Coast Guard, depending on the island location.

The study included island residents who regularly visited the aforementioned clinics between 1 April 2015 and 31 March 2020, and were 65 years or older at the time of inclusion. Regular visits were defined as at least one visit every 3 months for a minimum of 1 year. Participants were included between 1 April 2015 and 31 March 2019 to ensure a minimum observation period of 1 year, with data collection continuing to 31 March 2020.

Data collection

Data were collected using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) electronic data capture tool hosted at the University of the Ryukyus (https://www.project-redcap.org)13,14. REDCap is a web-based software platform with assured security designed to support data collection in research studies. The principal researcher visited each island clinic between July 2021 and October 2022 to collect data. The principal researcher (MI) reviewed all paper-based medical records and identified participants meeting the inclusion criteria. If original data were needed after the initial collection, collaborating researchers at each clinic were asked to retrieve it. Baseline characteristics were collected at the time of participant inclusion. Definitions of medical conditions are shown in Appendix II. Medications were classified according to the framework established by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare15.

Exposure

Exposure was polypharmacy status at baseline. While the definition of polypharmacy varies across studies, we adopted the most commonly used definition: the use of five or more prescribed medications5. Medications prescribed for less than 1 month at the time of inclusion were classified as temporary prescriptions and excluded from the count. We counted all oral medications, including weekly or monthly medications (eg bisphosphonates, methotrexate), certain inhaled medications (inhaled steroids, long-acting inhaled β2 agonists and long-acting inhaled anticholinergics), certain patch medications (isosorbide nitrate and rivastigmine), and select injectable medications (insulin, GLP-1 receptor agonists, subcutaneous biologic agents, teriparatide and anti-RANKL antibodies). Other patches or injectable medications were excluded from the analysis. Fixed-dose combinations were counted as separate medications (eg a combination of an angiotensin II receptor blocker and a calcium channel blocker was counted as two medications). The number of medications was determined from medical records, primarily reflecting prescriptions by island clinics; medications prescribed by off-island institutions were also included when documented to ensure an accurate total count.

Outcome

The primary outcome was non-returned off-island referrals. Off-island referrals were defined as same-day emergency or scheduled referrals from island clinics to core institutions or specialists off-island within 1 month. Non-returns were defined as relocations outside the islands or deaths off-island following off-island referrals, as confirmed by medical records or referral letter responses. Relocation refers to any move away from the islands, regardless of the destination, including private homes, nursing facilities, hospitals and other locations. If relocation or death off-island could not be verified through medical records or referral letter responses, statements from medical assistants regarding the patient’s status were used as references. The final diagnosis following referral was extracted from the returned referral letter; if multiple diagnoses were present, all diagnoses were recorded.

Variables

We collected baseline covariates – including age (continuous), sex (binary), activities of daily living (ADL; binary), dementia (binary), multimorbidity (binary) and presence of specific medical conditions (coronary artery disease (binary), stroke (binary), and malignancy (binary)) – to adjust the potential confounders. These covariates were selected based on their clinical relevance to the primary outcome. Patients documented as ‘not independent in daily life’ in physician statements regarding the degree of independence in daily living for disabled older adults16 related to long-term care insurance were defined as having a decline in ADL. The presence of multimorbidity was determined based on a list of 20 medical conditions created by modifying the list of medical conditions used in a previous study17 for data unavailable in this study (Appendix II). Multimorbidity is defined as the presence of two or more medical conditions. Coronary artery disease was defined as prior acute coronary syndrome, a history of percutaneous coronary intervention, a history of coronary artery bypass grafting, or stenosis of 75% or more based on coronary angiography. The presence of dementia, coronary artery disease, stroke and malignancy was confirmed by reviewing the patients’ medical records up to the inclusion date.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline participant characteristics (Table 1), with continuous variables reported as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables presented as frequencies and percentages. p-values were not calculated for Table 1 because significance judgements based on p-values depend on sample size and may not reflect clinically meaningful differences. The association between polypharmacy and non-return after off-island referrals was analyzed using logistic regression analysis, adjusting for age, sex, ADL, dementia, multimorbidity, coronary artery disease, stroke and malignancy. In addition to the main analysis, a supplemental analysis evaluated outcome trends across three groups based on the number of prescribed medications: 1–4 medications, 5–9 medications and 10 or more medications.

For participants with missing data, we conducted a complete case analysis excluding observations with missing values in the exposure (polypharmacy), outcome (non-returned off-island referrals) or key covariates (age and sex). For covariates – including ADL, dementia, multimorbidity, coronary artery disease, stroke and malignancy – we classified the presence or absence of each condition based on available medical records, minimizing the likelihood of missing data. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p-value less than 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using R v4.1.1(R Foundation for Statistical Computing, https://www.R-project.org).

Table 1: Study participants' characteristics

| Variable | Characteristic | Total (N=1566) mean±SD/n (%) | Non-polypharmacy (N=910) | Polypharmacy (N=656) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 77.7±8.2 | 76.3±8.3 | 79.5±7.6 | |

| Sex (female) | 874 (55.8) | 484 (53.2) | 390 (59.5) | |

| BMI | 24.8±3.9 | 24.5±3.6 | 25.3±4.1 | |

| Missing |

488 (31.2) |

267 (29.3) | 221 (33.7) | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 135.4±18.4 | 136.1±18.6 | 134.4±18.1 | |

| Missing |

2 (0.1) |

2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 115.8±28.9 | 119.8±28.9 | 110.4±28.1 | |

| Missing |

240 (15.3) |

148 (16.3) | 92 (14.0) | |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.9±0.8 | 5.7±0.7 | 6.0±0.9 | |

| Missing |

245 (15.6) |

148 (16.3) | 97 (14.8) | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 62.7±17.8 | 65.3±16.1 | 59.3±19.3 | |

| Missing |

182 (11.6) |

121 (13.3) | 61 (9.3) | |

| Smoking | Never smoker | 754 (48.1) | 444 (48.8) | 310 (47.3) |

| Current/ex-smoker |

400 (25.5) |

242 (26.6) | 158 (24.1) | |

| Missing |

412 (26.3) |

224 (24.6) | 188 (28.7) | |

| Habitual alcohol drinking (average of at least once per week) | No | 789 (50.4) | 440 (48.4) | 349 (53.2) |

| Yes |

236 (15.1) |

160 (17.6) | 76 (11.6) | |

| Missing |

541 (34.5) |

310 (34.1) | 231 (35.2) | |

| ADL, decline | 142 (9.1) | 56 (6.2) | 86 (13.1) | |

| Medical condition | Hypertension |

619 (39.6) |

372 (41.0) | 247 (37.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus |

185 (14.0) |

66 (8.7) | 119 (21.3) | |

| Dyslipidemia |

260 (19.6) |

179 (23.5) | 81 (14.4) | |

| Stroke |

177 (11.3) |

74 (8.1) | 103 (15.7) | |

| Obstructive pulmonary disease |

70 (4.5) |

26 (2.9) | 44 (6.7) | |

| Coronary artery disease |

79 (50.4) |

5 (0.5) | 74 (11.3) | |

| Chronic heart failure |

61 (3.9) |

9 (1.0) | 52 (7.9) | |

| Cirrhosis |

8 (0.5) |

0 (0) | 8 (1.2) | |

| Chronic kidney disease |

595 (38.0) |

291 (32.0) | 304 (46.3) | |

| Osteoporosis |

273 (17.4) |

94 (10.3) | 179 (27.3) | |

| Dementia |

127 (8.1) |

60 (6.6) | 67 (10.2) | |

| Malignancy |

112 (7.2) |

59 (6.5) | 53 (8.1) | |

| Multimorbidity | 1188 (75.9) | 578 (63.5) | 610 (93.0) | |

| Medications | Antihypertensive agents | 1263 (80.7) | 672 (73.8) | 591 (90.1) |

| Antidiabetic agents |

219 (14.0) |

62 (6.8) | 157 (23.9) | |

| Lipid-lowering agents |

519 (33.1) |

193 (21.2) | 326 (49.7) | |

| Diuretics |

255 (16.3) |

69 (7.6) | 186 (28.4) | |

| Antithrombotic agents |

336 (21.5) |

75 (8.2) | 261 (39.8) | |

| Antidepressants |

75 (4.8) |

16 (1.8) | 59 (9.0) | |

| Antipsychotics |

12 (0.8) |

3 (0.3) | 9 (1.4) | |

| Antiepileptics |

13 (0.8) |

4 (0.4) | 9 (1.4) | |

| Benzodiazepines |

186 (11.9) |

64 (7.0) | 122 (18.6) | |

| Non-benzodiazepine hypnotics |

59 (3.8) |

18 (2.0) | 41 (6.2) | |

| Antihistamines |

29 (1.9) |

11 (1.2) | 18 (2.7) | |

| Analgesics |

181 (11.6) |

43 (4.7) | 138 (21.0) |

ADL, activities of daily living. BMI, body mass index. LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted with the approval of the Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Ryukyus (approval no. 1433) and the Research Ethics Committees of the four core hospitals of the remote island clinics: Okinawa Prefectural Nanbu Medical Center & Children's Medical Center (approval no. R3-024), Okinawa Prefectural Chubu Hospital  Okinawa Prefectural Miyako Hospital (approval no. not applicable), and Okinawa Prefectural Yaeyama Hospital (approval no. 5). The requirement for written informed consent was waived due to the study design.

Okinawa Prefectural Miyako Hospital (approval no. not applicable), and Okinawa Prefectural Yaeyama Hospital (approval no. 5). The requirement for written informed consent was waived due to the study design.

Results

Baseline characteristics

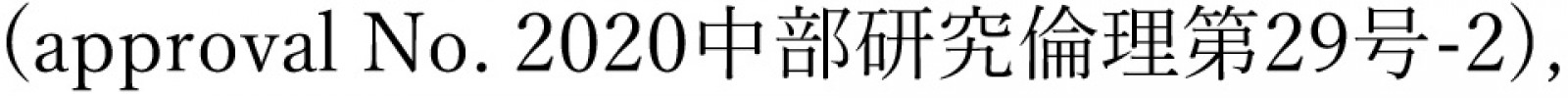

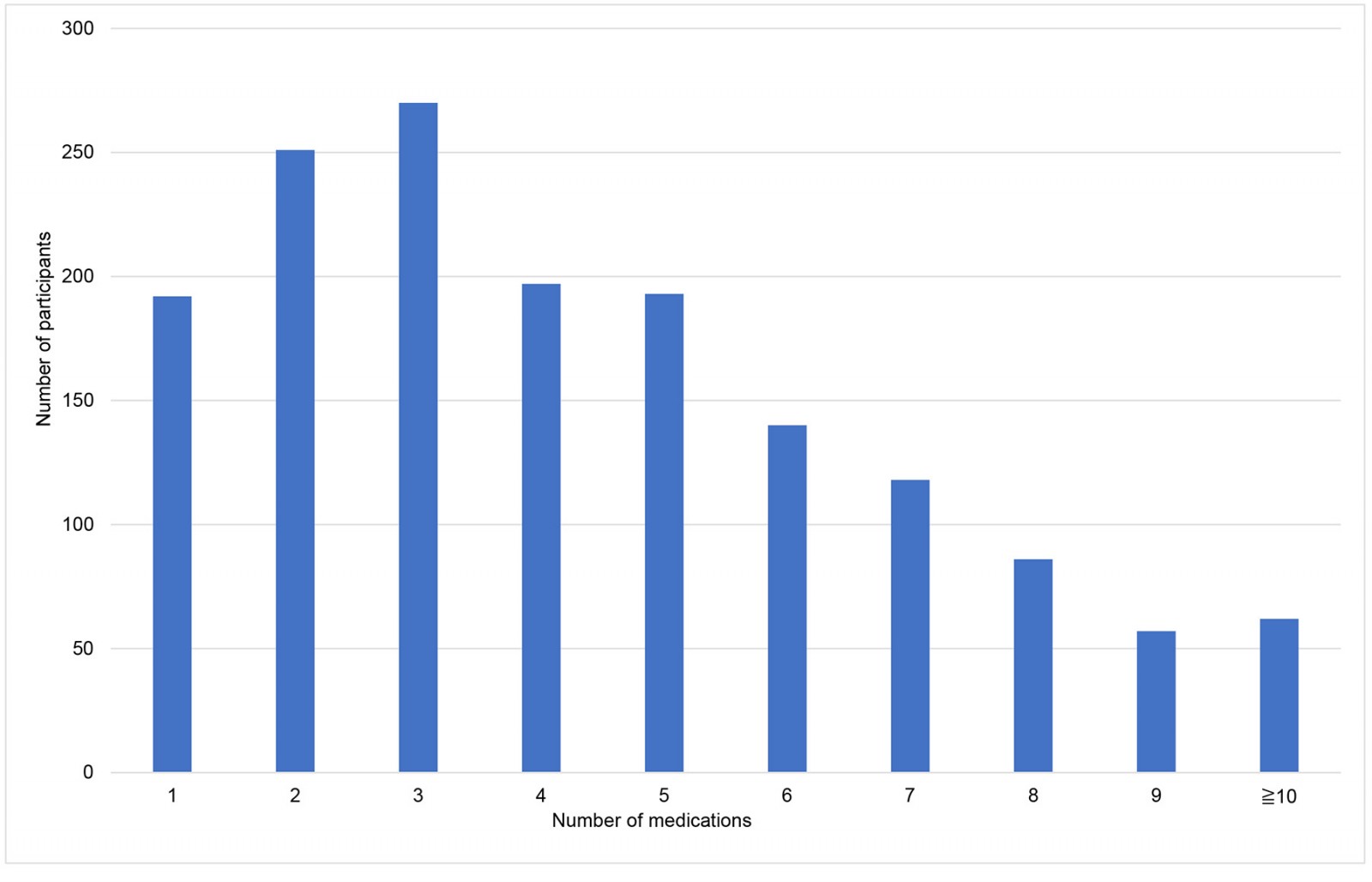

As of 1 April 2015, the total population across the 13 target islands was 10,022, of whom 2322 (23.2%) were aged 65 years or older18. The study enrolled 1566 participants who visited the clinics regularly, and with a median observation period of 5 years (mean 4.1 years). Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of participants according to the number of medications administered at baseline. Among all participants, 656 (41.9%) experienced polypharmacy. No missing exposure data was observed. The baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A total of 578 of 910 (63.5%) and 610 of 656 (93.0%) participants had multimorbidity in the non-polypharmacy and polypharmacy groups, respectively. As illustrated in Figure 2, the number of prescribed medications increases with the number of medical conditions.

Figure 1: Number of study participants by number of medications.

Figure 1: Number of study participants by number of medications.

Figure 2: Number of medications by number of medical conditions.

Figure 2: Number of medications by number of medical conditions.

Outcome

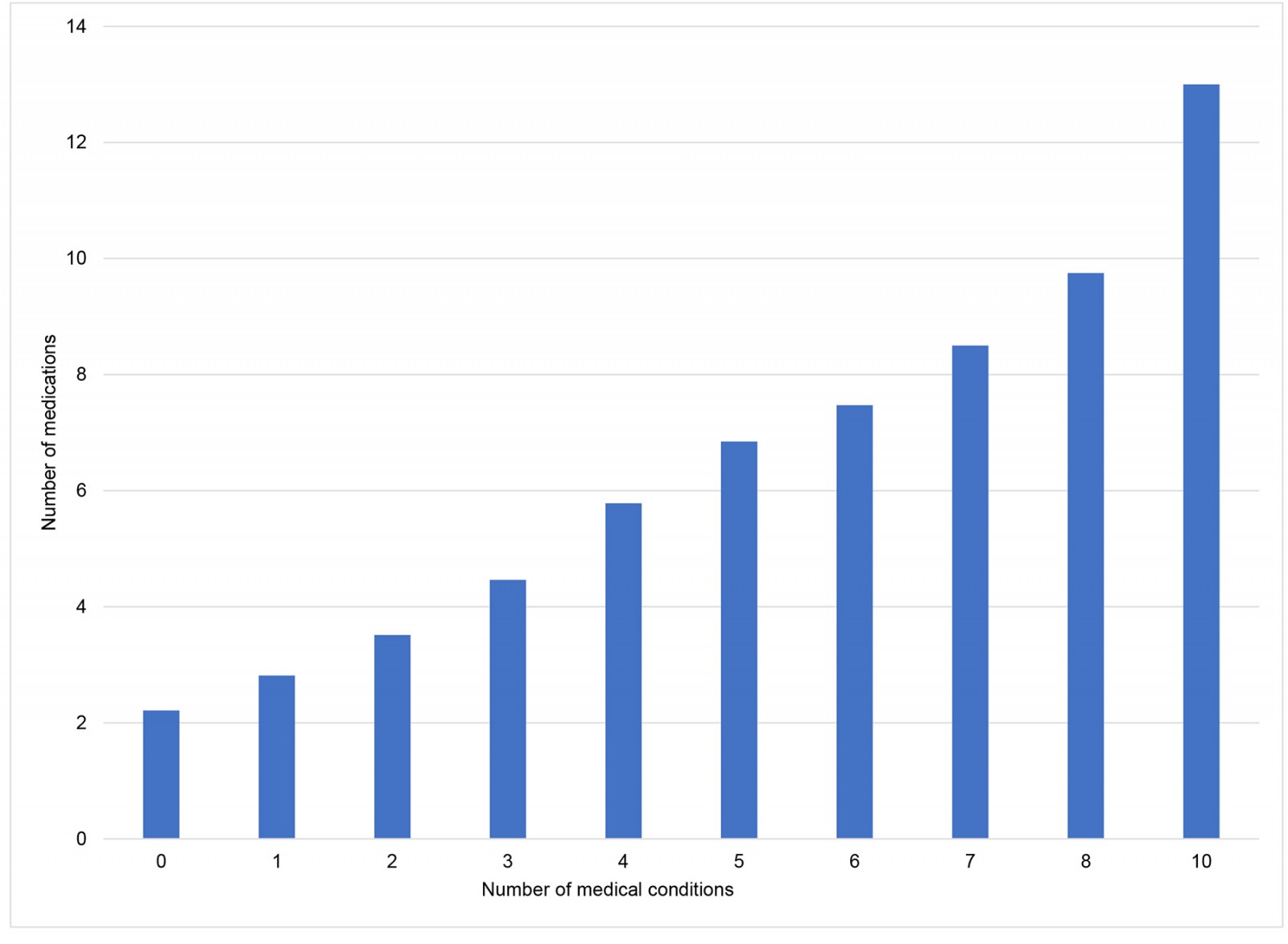

During the observation period, 181 of 1566 (11.6%) participants resulted in non-returned off-island referrals. Among 1385 participants who did not experience the primary outcome, 1114 reached the end of the observation period, 46 returned to the islands after off-island referrals but changed outpatient visits to off-island (eg post-myocardial infarction follow-up with an off-island cardiologist), 79 relocated off-island for reasons unrelated to referral, 61 died on the islands, 16 discontinued regular outpatient visits due to loss of necessity, and 69 were lost to follow-up during the observation period. Among 181 participants who experienced the primary outcome, 44 died at the referring institution off the island, and 137 were relocated off the island after being discharged from the referring institutions. Figure 3 provides a detailed breakdown of 134 out of the 181 patients for whom referral letters with final diagnoses were returned. Bone fractures were the most common health events resulting in non-returned off-island referrals, followed by pneumonia/bronchitis, acute heart failure and cerebral infarction/transient ischemic attacks. Among 181 participants with non-returned off-island referrals, 69 were classified as non-polypharmacy and 112 were classified as polypharmacy.

Figure 3: Reasons for non-returned off-island referrals.

Figure 3: Reasons for non-returned off-island referrals.

Relationship between polypharmacy and non-returned off-island referrals

The results of the logistic regression analysis are summarized in Table 2. In model 1, the unadjusted odds ratio (OR) for the outcome in the polypharmacy group compared to the non-polypharmacy group was 2.51 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.83–3.46). After adjusting for age, sex, ADL and dementia in model 2, the adjusted OR (aOR) was 2.09 (95%CI: 1.50–2.93). In model 3, which additionally adjusted for multimorbidity, coronary artery disease, stroke and malignancy, the aOR was 1.98 (95%CI: 1.38–2.85). Stratification of participants into three groups (1–4 medications, 5–9 medications and ≥10 medications) revealed non-returned off-island referral rates of 6%, 16.7% and 21.0%, respectively. Adjusted ORs progressively increased from the 1–4 medication group to the 5–9 medication group and the ≥10 medication group across all models (Appendix III).

Table 2: Association between non-returned off-island referral and polypharmacy

| Number of medications | No return (N=181) n (%) | Model 1† OR (95%CI) | Model 2¶ OR (95%CI) | Model 3§ OR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–4 (N=910) | 69 (7.6) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| ≥5 (N=656) | 112 (17.1) | 2.51 (1.83–3.46) | 2.09 (1.50–2.93) | 1.98 (1.38–2.85) |

† Model 1 is unadjusted.

¶ Model 2 is adjusted for age, sex, ADL and dementia.

§ Model 3 is adjusted for model 2 as well as multimorbidity, coronary artery disease, stroke and malignancy.

ADL, activities of daily living. CI, confidence interval. OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

Summary of results

A significant association was identified between baseline polypharmacy and the likelihood of non-returned off-island referrals in the remote islands of Okinawa. The study revealed that bone fractures, pneumonia or bronchitis, and acute heart failure, were the most frequent causes of non-returned off-island referrals.

Comparison with previous study

No previous studies have specifically evaluated the association between polypharmacy and health events that lead to non-returned off-island referrals in remote island settings. However, a cohort study of approximately three million older adults in South Korea based on national health insurance data reported a significant association between polypharmacy and both hospitalization and all-cause mortality7. Given that most off-island relocations in this study likely occurred following hospitalization, and death was included as an outcome, our findings are consistent with those of the South Korean study.

Although this study identified an association between polypharmacy and an increased risk of non-returned off-island referrals among older island residents, the findings did not demonstrate that polypharmacy interventions reduce such referrals. Previous investigations have not conclusively shown that polypharmacy interventions improve mortality or other health outcomes19,20. This study emphasized an association, not a causal relationship, between polypharmacy and non-returned off-island referrals. Further research is necessary to determine whether targeted polypharmacy interventions can mitigate the outcome.

Consideration of confounders

Adjustment for the number and severity of medical conditions is essential when evaluating the relationship between polypharmacy and clinical outcomes to control for confounding and isolate the effect of polypharmacy. Polypharmacy is often considered a consequence of multimorbidity, as patients with multiple medical conditions typically receive multiple medications. Although previous studies have reported associations between these variables21,22, a causal relationship remains unestablished, likely due to their concurrent progression, which complicates the identification of temporal causality.

In this study, the number and severity of medical conditions, including multimorbidity, were considered both contributors to polypharmacy and independent prognostic factors for the outcome. Therefore, these factors were adjusted for as confounders in the analysis. Previous studies have applied diverse methods for such adjustment, with no consensus on the optimal approach23. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)24, a widely used measure incorporating disease severity, was not applied due to limitations in data collection. Furthermore, the CCI’s primary function – mortality prediction – did not align with the outcome of interest, which was non-returned off-island referrals. Instead, clinically significant medical conditions and the presence of multimorbidity were adjusted as confounding variables in this study. Nevertheless, the influence of the number and severity of medical conditions on the outcome could not be fully eliminated.

Given that the outcome in this study encompassed a broad spectrum of health events, the observed association likely reflects both the direct effects of polypharmacy and the influence of the number and severity of medical conditions. For instance, bone fractures, which are the leading cause of non-returned off-island referrals, may be associated with benzodiazepines, which increase fall risk25, whereas acute heart failure may reflect underlying cardiovascular comorbidities. This study evaluated the relationship between polypharmacy and non-returned off-island referrals across a range of clinical events, rather than focusing on specific etiologies.

Although incomplete adjustment for confounders limits estimation of the isolated effect of polypharmacy, the findings retain substantial clinical value. Comprehensive assessment of the number and severity of medical conditions is challenging due to definitional variability and the complexity of severity classification. In contrast, polypharmacy serves as a practical and objective measure, readily quantified by the number of prescribed medications. This facilitates prompt risk identification in clinical settings. Early detection of polypharmacy may prompt clinicians to address other modifiable risk factors, potentially mitigating the outcome.

Strengths

The strengths of this study include its relatively longer follow-up period compared to previous studies26 and the accuracy of measuring both exposure and outcomes. In Japan, due to open access to medical facilities27, it is challenging to accurately capture patients’ medication use and health events simultaneously using medical records or national databases. However, in a remote island setting with a closed healthcare system, medication prescriptions and off-island referrals are largely limited to island clinics unless residents travel off-island. Thus, using medical record data from a remote island, this study captured accurate information on exposure and outcomes. In addition, the outcomes of non-returned off-island referrals are highly relevant to older island residents. The percentage of residents in Japan who wish to remain in their own homes at the end of life is 54.6%28. Evidence suggests that a higher percentage of older residents living on remote islands prefer home-based end-of-life care compared to those living in urban areas29. Thus, living at home in a familiar area is considered a more profound desire among older island residents than among older residents living on the mainland.

Limitations

This study has certain limitations. First, the number of prescribed medications was assessed only at the time of inclusion, without accounting for changes in medication regimens during the follow-up period before the outcome. Second, medication data were extracted exclusively from the clinical medical records, excluding over-the-counter medications and medications prescribed by off-island providers. However, due to the geographic isolation of the islands, the likelihood of undercounting medications was lower among the study participants on the islands than among residents in non-island areas with access to multiple healthcare providers. Third, this study evaluated only the association between polypharmacy and outcomes, without considering medication dose, efficacy or adherence. Finally, some potential confounding factors, including socioeconomic status, family structure and access to welfare service such as nursing home or home care visit, could not be adjusted. The ability to return to the island after off-island referrals may vary based on these factors, indicating that measuring and incorporating these factors into confounding adjustments could enhance validity.

Implications

The significant association between polypharmacy and non-returned off-island referrals among remote island residents suggests that older island residents with polypharmacy are at higher risk of non-returned off-island referrals. If physicians managing older island residents with polypharmacy recognize this association and effectively communicate it to these patients, both physicians and patients may better anticipate potential non-returned off-island referrals or mitigate these outcomes by addressing other modifiable risk factors. Future research should clarify whether reducing the number of medications can decrease the risk of non-returned off-island referrals. This study does not imply that medication reduction alone would necessarily improve the outcome.

Conclusion

This study identified the breakdown and frequency of health events leading to non-returned off-island referrals and observed a significant association between polypharmacy and non-returned off-island referrals. Physicians managing older island residents with polypharmacy should be aware of the increased risk of non-returning off-island referrals.

Acknowledgements

We thank Takamitsu Miyake, Masato Nimura, Keita Yamashiro, Sayaka Tago, Akane Kikuchi, Masaki Ishihara, Shigeru Yutani, Kentaro Osada, Tomofumi Funakoshi, Rinko Koyama, Tetsuya Kikuchi, Miyuki Shimosato, Yusuke Yamanaka, Toshinori Ariji, Haruka Ariji, Sotaro Oshima, Miyu Yoshimi, Masaki Matsushita and Kanetaka Kuba for their assistance with data collection. We acknowledge the support of Editage for the English editing of this manuscript. We used ChatGPT-4o to proofread this manuscript in English. All revisions were carefully reviewed and verified by the authors.

Funding

The Okinawa Prefectural Government supported this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.