Dear Editor

Delivering medical education in community medicine is essential for advancing the discipline1. However, balancing the educational responsibilities with the practical demands of community medicine poses significant challenges. Understanding the stress associated with the provision of education in this field is crucial for future development.

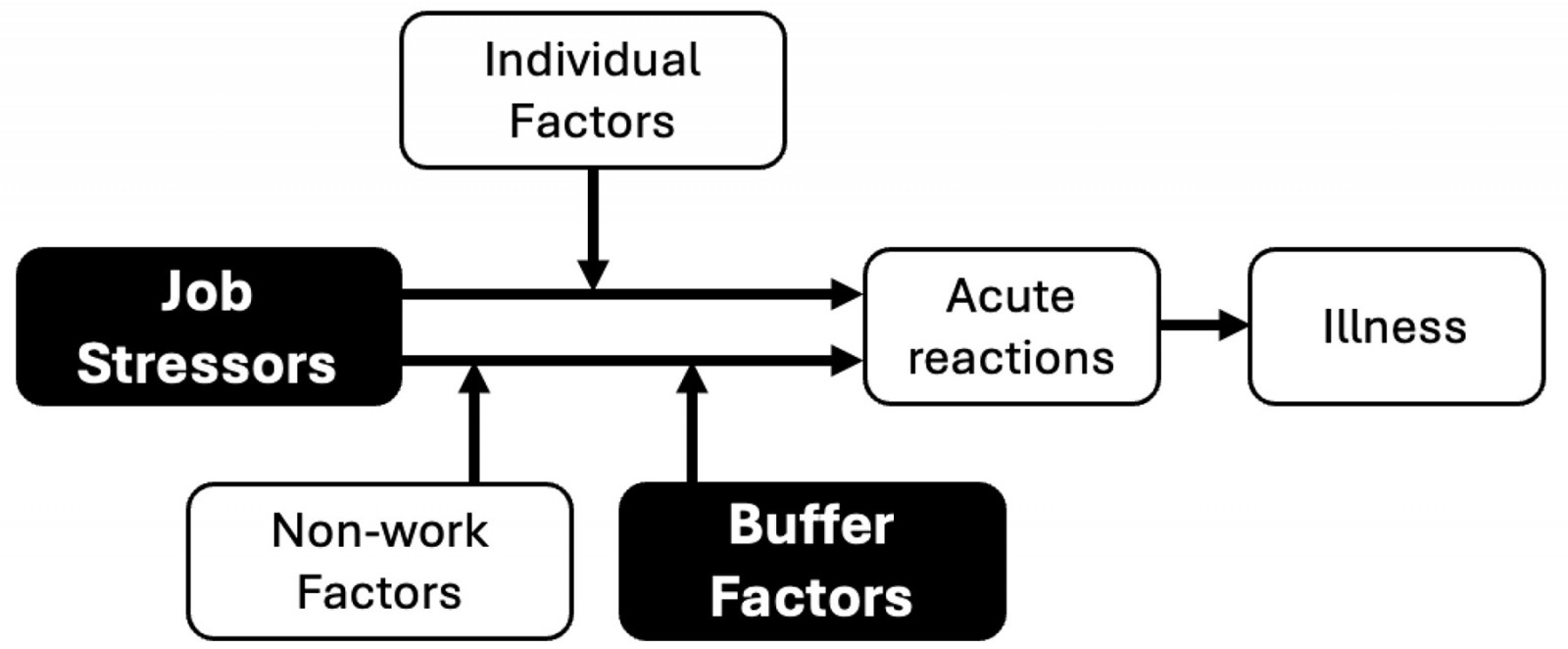

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) job stress model identifies various stressors in healthcare settings, including excessive workload, long hours, limited job control, and ineffective organizational management2. These stressors are linked to severe health issues such as cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, and mental health problems3. To mitigate these challenges, NIOSH recommends promoting work–life balance, fostering social support, and cultivating a positive mindset. Additionally, organizational interventions such as aligning workloads with staff capacity, enhancing job roles, and improving communication are vital. NIOSH emphasizes the importance of integrating stress management with organizational redesign to strengthen workplace health.

In this study, we applied the NIOSH model, focusing on job stressors and buffer factors, which are relatively easy to modify (Fig1). We conducted group discussions with 10 community-based attending physicians who provided care and medical education in community hospitals and clinics, focusing on local healthcare needs. We also engaged five faculty members in community medicine education to explore the stress and buffering factors related to community-oriented medical education. The physicians, all experts in community medicine and medical education, had at least 1 year of experience and participated in a weekly faculty development program. They were divided into two groups of three and five, to engage in online discussions. The outcomes of both groups are summarized collectively (Table 1).

One key finding was that the demanding clinical responsibilities of community-attending physicians limited the time they spent on educational activities4. They also encountered unfamiliar tasks such as attending academic conferences and hosting international delegations focused on community-oriented medical education. A significant stressor was the lack of understanding of medical education among colleagues, including senior management, multidisciplinary staff, and administrative personnel at regional hospitals1. Additionally, unprofessional behavior from learners was noted as a source of stress.

Conversely, an essential stress-relieving factor was the effective management of resources, including interprofessional education with strong psychological connections and open communication among attending physicians, healthcare staff, and supervisors1,4. Educational exchanges and horizontal connections between community-attending physicians and university hospitals emerged as important buffering factors. Loneliness, a common experience in community settings, has been recognized as a risk factor for burnout, highlighting the importance of social interactions fostered by educational activities. Notably, understanding from senior management was identified as a stress buffer, whereas its absence was a significant stressor. Leadership attitudes toward medical education, their support, and their comprehension of the unique challenges in community medicine are crucial for the advancement of community medical education5.

To our knowledge, this letter presents the first discussion on stressors and buffers among community-attending physicians. It suggests that fostering understanding among superiors and various professionals is vital for creating a low-stress environment in community medical education. These insights guide the sustainability and enhancement of educational practices, advancing community medicine.

Table 1: Job stressors and buffer factors for community-attending physicians

| Job stressors |

|---|

|

| Buffer factors |

|

Figure 1: Model of job stress and health by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Figure 1: Model of job stress and health by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Dr Nobuyuki Araki, Dr Kiyoshi Shikino and Dr Kazuyo Yamauchi, Department of Community-Oriented Medical Education, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan